Navigating Technological Frontiers: Explainable Patent Recommendation with Temporal Dynamics and Uncertainty Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We propose TEAHG-EPR, an end-to-end framework that unifies structural, attribute, and temporal dimensions of patent data to address the limitations of static modeling.

- (2)

- We innovatively introduce uncertainty modeling into patent recommendation, utilizing Gaussian distributions to balance accuracy with the discovery of potential technological opportunities.

- (3)

- We design a controllable explanation module that generates relevant and traceable textual rationales, significantly enhancing system trustworthiness.

- (4)

- We demonstrate through experiments on real-world industrial (USPTO) and academic (AMiner) datasets that TEAHG-EPR outperforms state-of-the-art baselines in accuracy, diversity, and explanation quality.

2. Related Works

2.1. Graph-Based Patent Mining and Knowledge Representation

2.2. Content-Based and Hybrid Recommendation Architectures

2.3. Dynamic Graph Learning and Temporal Evolution

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Definition and Framework

3.1.1. Problem Definition

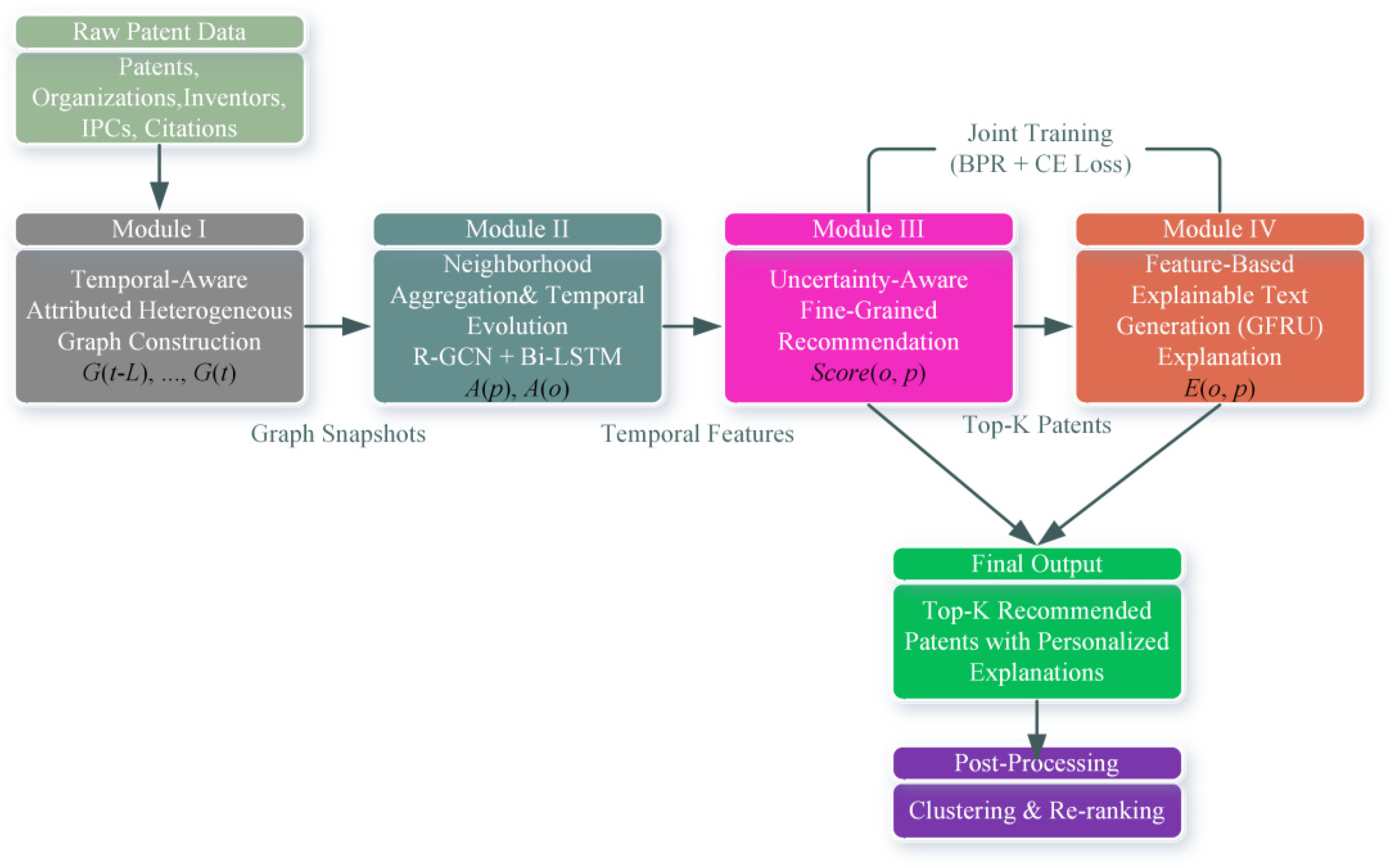

3.1.2. Overall Framework

3.2. Constructing the Temporal-Aware Attributed Heterogeneous Graph

3.2.1. Patent Heterogeneous Graph

- (1)

- r1 (TransferOut): An organization transferring out a patent. A triplet (o, r1, p) means organization o was the seller of patent p.

- (2)

- r2 (TransferIn): The inverse, where an organization acquires a patent. So, (o, r2, p) indicates organization o obtained patent p.

- (3)

- r3 (InventedBy): The straightforward link between a patent and its creators, (p, r3, i).

- (4)

- r4 (BelongsTo): Connects a patent to its technical field via an IPC code, (p, r4, c).

- (5)

- r5 (OwnedBy): Represents the ownership link between a patent and its assignee, (p, r5, a).

- (6)

- r6 (Cites): The crucial citation link, where (pi, r4, pj) means patent i references patent j.

3.2.2. Attribute System

- (1)

- Technical Scope (A1): The number of unique 4-digit IPC classes a patent belongs to, which gives a sense of its technological breadth.

- (2)

- Number of Claims (A2): The total count of independent and dependent claims.

- (3)

- Patent Document Quality (A3): Measured by the total page count of the specification and claims.

- (4)

- Patent Competitiveness (A4): A composite score based on the strength of the assignee’s patent portfolio, detailed calculations are as follows.

- (5)

- Technological Novelty (A5): A score calculated from the textual similarity of the patent’s abstract to prior art, detailed calculations are as follows.

- (6)

- Grant Lag (A6): The time in years from the application date to the grant date.

- (7)

- Number of Inventors (A7): The size of the invention team.

- (8)

- Agent Status (A8): A binary variable indicating whether a patent agent was involved.

- (9)

- Forward Citations (A9): The number of times the patent is cited by later patents.

- (10)

- Backward Citations (A10): The number of prior art documents the patent cites.

- (1)

- Geographic Region (A11): The organization’s location, encoded at the city level.

- (2)

- Organization Type (A12): Categorized as a company, university, research institute, or individual.

- (3)

- Patent Textual Features (A13): A vector representation derived from the abstracts of the organization’s historical patent portfolio.

3.2.3. Temporal Knowledge Graph

- (1)

- : Set of existing nodes (entities) as of year t.

- (2)

- : Set of existing edges (facts triples) as of the year t.

- (3)

- : The entity attribute matrix as of year t.

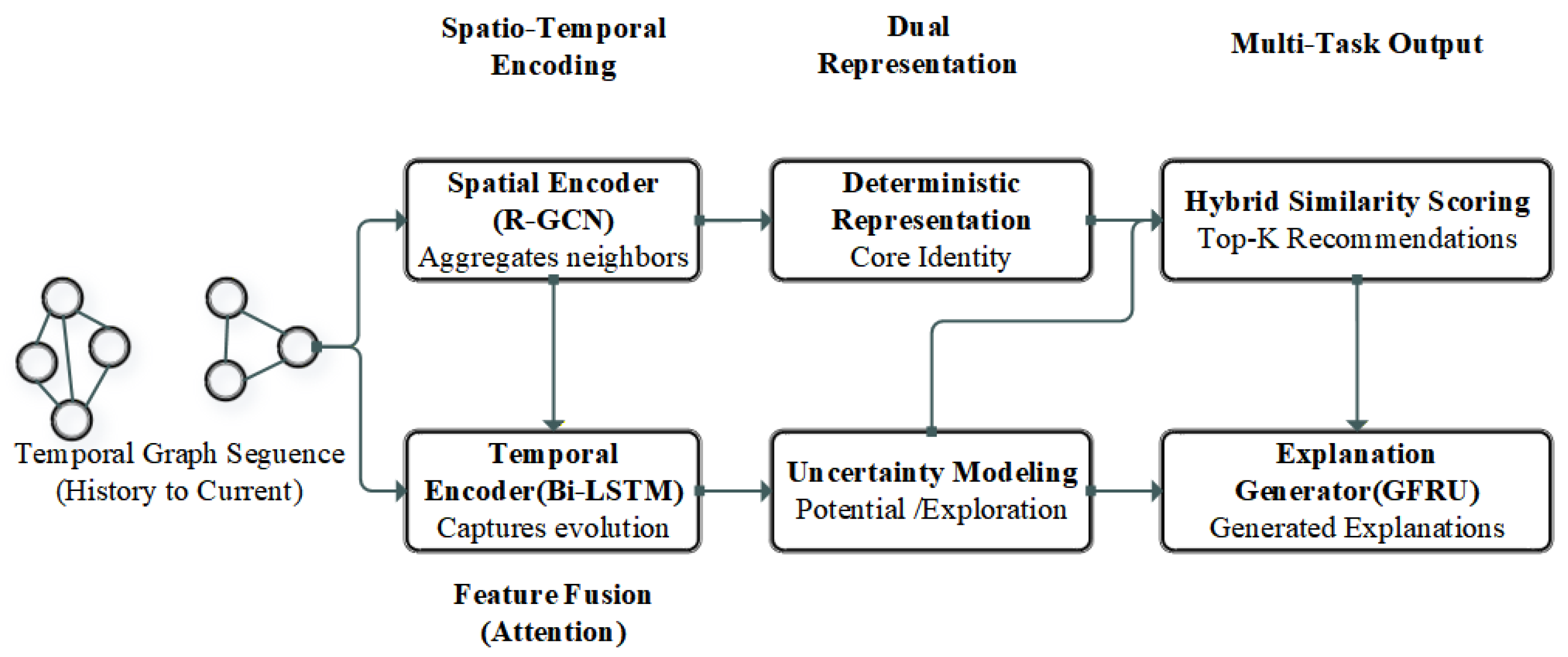

3.3. Neighborhood Aggregation and Temporal Evolution Representation

3.3.1. Graph Neighborhood Aggregation Based on R-GCN

3.3.2. Temporal Evolution Representation Based on Bidirectional LSTM

- (1)

- Building Relation-Specific Time Series

- (2)

- Encoding Temporal Patterns with Bi-LSTM

- (3)

- Aggregating Multi-Dimensional Temporal Features

3.4. The Uncertainty-Aware Fine-Grained Recommendation Module

3.4.1. Fine-Grained Information Aggregation and Multi-Head Attention Mechanism

- (1)

- Body Representation: For a patent p, we take its feature vector straight from the final layer of the R-GCN module, specifically from its application on the latest time snapshot, G(t). We call this . This vector primarily encodes the patent’s static neighborhood structure at the current moment—think of it as its core identity.

- (2)

- Temporal Evolving Attribute Representation: For the same patent p, we use the temporal evolution feature matrix that we constructed in the previous section. This matrix holds the dynamic history of its m different types of neighbors (like inventors, IPCs, etc.) over the observed time window.

3.4.2. Node Uncertainty Modeling Based on Multi-Dimensional Gaussian Distribution

3.4.3. Organization—Patent Similarity Calculation and Recommendation List Generation

- (1)

- Deterministic Core Relevance Measurement

- (2)

- Probabilistic Potential Matching Measurement

- (3)

- Hybrid Recommendation Score and List Generation

3.5. Feature-Based Explainable Text Generation

3.5.1. Construction of Patent Technical Feature Document

3.5.2. Extraction of Technical Characteristic Words Based on PMI

3.5.3. Explanation Text Generation Based on GFRU

- (1)

- Encoding Stage: Initializing the Decoder State

- (2)

- Decoding Stage: Controllable Sequence Generation

- (1)

- The Context GRU: This is a standard GRU that takes the previous word xn−1 and hidden state hn−1 to produce a new candidate hidden state . Its main job is to ensure the output sentence is grammatically correct and fluent.

- (2)

- The Feature GRU: This GRU works in parallel. Instead of the previous word, it takes the constant feature topic vector xf as input at every step, along with the previous hidden state hn−1. Its job is to produce a candidate hidden state that is infused with the semantics of our keywords.Its structure is identical to the context GRU, but its parameters are independent.

- (3)

- The Gated Fusion Unit (GFU): This is where the magic happens. The GFU takes the outputs of both GRUs, and , and dynamically decides how much to listen to each.

3.5.4. Loss Fuction for Explanation Generation

3.6. Model Training and Optimization

3.6.1. Joint Training Strategy

3.6.2. Optimization Algorithms and Hyperparameter Settings

3.6.3. Training Process

| Algorithm 1: TEAHG-EPR Model Training Algorithm |

| Input: Temporal patent knowledge graph sequence Gseq, Training set = {(o, p+) | o has an interaction with p+}, Validation set , Hyperparameter set Θconfig. |

| Output: Trained model parameters Θ*. |

| 1: Initialize model parameters Θ 2: // Main training loop begins 3: for epoch = 1 to max_epochs do 4: // Recommendation Module Training 5: for each mini-batch in do 6: For each positive pair (o, p+), sample a negative patent p− to form triplets {(o, p+, p−)} 7: // Step 1: Extract Deterministic Features 8: Apply R-GCN to each graph snapshot in Gseq to get yearly node features {H(t)} 9: Use Bi-LSTM to extract temporal evolution features A(o), A(p+), A(p−) for all entities in the triplets 10: Aggregate fine-grained information via multi-head attention to get M(o), M(p+), M(p−) 11: Concatenate and fuse to compute the final deterministic feature representations I(o), I(p+), I(p−) 12: // Step 2: Generate Probabilistic Representations and Compute Scores 13: Project the deterministic features I(.) to Gaussian distribution parameters (μ(.),Σ(.)) 14: Calculate deterministic similarities simdet(o, p+) and simdet(o, p−) 15: Calculate probabilistic similarities simprob(o, p+) and simprob(o, p−) 16: Compute the final recommendation scores score(o, p+) and score(o, p−) 17: // Step 3: Compute Recommendation Loss 18: Calculate the recommendation loss using the BPR loss function 19: end for 20: 21: // Explanation Generation Module Training 22: for each mini-batch in do 23: For each positive pair (o, p+), extract its technical feature words 24: Use the already computed I(o), I(p+) as the initial input for the GFRU 25: Generate the explanation text with the GFRU and compute the cross-entropy loss 26: end for 27: 28: // Joint Optimization 29: Compute the total loss 30: Perform a single backpropagation step and update all shared parameters Θ using the Adam optimizer 31: 32: // Validation and Early Stopping 33: Evaluate recommendation performance on the validation set 34: if performance has not improved for a specified number of epochs then 35: break 36: end if 37: Update learning rate (cosine annealing) 38: end for 39: 40: return trained model parameters Θ* |

3.7. Personalization and Diversity Optimization

3.7.1. Personalized Recommendation Based on Organizational Clustering

- (1)

- Intra-List Similarity (IntraSim): This measures the average similarity within a recommended list, giving us a handle on its diversity:

- (2)

- Popularity: This measures the average popularity of the recommended patents, indicating how much the model leans towards mainstream or niche items.

- (1)

- Mediators: High diversity, high popularity. These organizations tend to acquire a broad portfolio of well-known, popular patents.

- (2)

- Domain Leaders: Low diversity, high popularity. Their focus is narrow and deep, concentrating on the core, essential patents within their specific field.

- (3)

- Explorers: High diversity, low popularity. These are often research-oriented entities, constantly scouting for a wide range of novel, cutting-edge technologies that may not be popular yet.

- (4)

- Niche Specialists: Low diversity, low popularity. These organizations carve out a space for themselves by focusing intensely on a specific, often obscure, technological niche.

- (5)

- Emerging Players: Medium diversity, medium popularity. These organizations are typically in a technology accumulation phase, building out their portfolio.

- (6)

- Focused Experts: Extremely low diversity, medium popularity. They follow a highly specialized technological path, concentrating on a very narrow set of technologies.

3.7.2. Re-Ranking and Quality Filtering of Explanations

3.8. Model Complexity Analysis

- (1)

- R-GCN Aggregation: For an R-GCN with L layers, the complexity per layer is roughly , leading to a total of , where is the number of edges.

- (2)

- Bi-LSTM Encoding: For a sequence of length nT, the complexity is .

- (3)

- Multi-Head Attention: This comes in at , where m is the number of relation types.

- (4)

- GFRU Generation: For an explanation of length , the complexity is .

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. USPTO-Semiconductor Patent Dataset

4.1.2. AMiner-DBLP Dataset

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.2.1. Recommendation Performance Metrics

4.2.2. Explanation Quality Metrics

4.2.3. Diversity and Novelty Metrics

4.3. Baselines for Comparison

4.3.1. General Recommendation Models

- (1)

- BPR-MF [52]: A true classic in the recommendation systems field. This model learns latent vectors for users and items through matrix factorization, optimized with a Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) loss. In our setup, organizations are the “users” and patents are the “items.” BPR-MF is our foundational baseline, helping us measure the performance lift gained by moving to more complex, deep learning-based models.

- (2)

- LightGCN [58]: As a standard-bearer for graph collaborative filtering, LightGCN has made waves by simplifying the graph convolution mechanism. It learns embeddings by propagating them only on a user-item bipartite graph, which has proven to be both efficient and highly effective. For us, LightGCN represents the state of the art in general-purpose graph recommendation. Comparing against it will highlight the benefits of our more complex design, which explicitly handles the heterogeneous and temporal aspects of the data.

4.3.2. Sequential Recommendation Models

4.3.3. Heterogeneous Graph/KG Models

4.3.4. Explainable Recommendation Models

4.4. Implementation Details

4.5. Ablation Experiments

4.6. Overall Performance Comparison

4.6.1. Analysis of Recommendation Performance

4.6.2. Analysis of Explanation Quality

4.6.3. Faithfulness Evaluation

4.7. Model Analysis and Discussion

4.7.1. Analysis of Hyperparameter Sensitivity

4.7.2. Analysis of Personalization and Diversity

4.7.3. Cold-Start Performance Analysis

4.8. Case Study

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y. The Transition of the Patent System; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J. Experience & Abstraction: A Study of Speculative Knowledge Production in Reconceptualising Our Relation to the World. Ph.D. Dissertation, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Innovation through research and development. In Signals and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 10, pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sherriff, G. How to read a patent: A survey of the textual characteristics of patent documents and strategies for comprehension. J. Patent Trademark Resour. Cent. Assoc. 2024, 34, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Tufail, A.; De Silva, L.C.; Ahmed, S.; Khan, M.A.; Zafar, A.; Iqbal, S.; Rehman, A.; Khan, S.; Mahmood, T. Innovating patent retrieval: A comprehensive review of techniques, trends, and challenges in prior art searches. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Shao, Z. Patent text mining based hydrogen energy technology evolution path identification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wu, X.; Wen, P. Patent Technology Knowledge Recommendation by Integrating Large Language Models and Knowledge Graphs. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5603825 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Chung, J.; Choi, J.; Yoon, J. Exploring intra-and inter-organizational collaboration opportunities across a technological knowledge ecosystem: A metapath2vec approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 298, 129724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, F. Knowledge graphs and their applications in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dong, H.; Hastings, J.; Karp, P.D.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Ding, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, J. Knowledge graphs for the life sciences: Recent developments, challenges and opportunities. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.17255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejriwal, M. Knowledge graphs: A practical review of the research landscape. Information 2022, 13, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, W. A comprehensive survey on automatic knowledge graph construction. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichtkrull, M.; Kipf, T.N.; Bloem, P.; van den Berg, R.; Titov, I.; Welling, M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In European Semantic Web Conference; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 593–607. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Generate neural template explanations for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Virtual Event, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 755–764. [Google Scholar]

- Madani, F.; Weber, C. The evolution of patent mining: Applying bibliometrics analysis and keyword network analysis. World Patent Inf. 2016, 46, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.; Alberts, S.C. Social network dynamics: The importance of distinguishing between heterogeneous and homogeneous changes. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2015, 69, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, V.; Rosenberg, C. Homogeneous vs heterogeneous clustered sensor networks: A comparative study. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Paris, France, 20–24 June 2004; Volume 6, pp. 3646–3651. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, J.; Cai, Y.; Su, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Predicting user-item links in recommender systems based on similarity-network resource allocation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 158, 112032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, J. Mining heterogeneous information networks: A structural analysis approach. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newslett. 2013, 14, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. Meta paths and meta structures: Analysing large heterogeneous information networks. In Asia-Pacific Web (APWeb) and Web-Age Information Management (WAIM) Joint Conference on Web and Big Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. HKGAT: Heterogeneous knowledge graph attention network for explainable recommendation system. Appl. Intell. 2025, 55, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, J. Mining Heterogeneous Information Networks: Principles and Methodologies; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: Rafael, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Yu, P.S. A survey of heterogeneous information network analysis. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2016, 29, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creusen, M.E.H. The importance of product aspects in choice: The influence of demographic characteristics. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevic, M.; Sina, L.B.; Secco, C.A.; Tosato, P.; Ghidini, C.; Prandi, C.; Salomoni, P. Recommendation of scientific publications—A real-time text analysis and publication recommendation system. Electronics 2023, 12, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qi, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. AlignFusionNet: Efficient Cross-modal Alignment and Fusion for 3D Semantic Occupancy Prediction. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 125003–125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Han, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. KTMN: Knowledge-driven Two-stage Modulation Network for visual question answering. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrochidis, S.; Papadopoulos, S.; Moumtzidou, A.; Kompatsiaris, Y. Towards content-based patent image retrieval: A framework perspective. World Patent Inf. 2010, 32, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. A personalized recommendation system for high-quality patent trading by leveraging hybrid patent analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 9369–9391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, J. Doc2vec-based link prediction approach using SAO structures: Application to patent network. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 5385–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. Joint representation learning of cross-lingual words and entities via attentive distant supervision. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.H.; Baldwin, T. An empirical evaluation of doc2vec with practical insights into document embedding generation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.05368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnejad, R.; Habibizad Navin, A.; Rasouli Heikalabad, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Karimi, H. Combining 2-Opt and Inversion Neighborhood Searches with Discrete Gorilla Troops Optimization for the Traveling Salesman Problem. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4980127 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.-S. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 26th International World Wide Web Conference, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, K. Choosing the right collaboration partner for innovation: A framework based on topic analysis and link prediction. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 5519–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zang, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z. Research on digital matching methods integrating user intent and patent technology characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, A.M.; Albino, V.; Carbonara, N. Technology districts: Proximity and knowledge access. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Park, H.; Kim, K. Identifying technological competition trends for R&D planning using dynamic patent maps: SAO-based content analysis. Scientometrics 2013, 94, 313–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Q. Patentminer: Topic-driven patent analysis and mining. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Beijing, China, 12–16 August 2012; pp. 1366–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, M.; Cricelli, L.; Rogo, F. Valuating and analyzing the patent portfolio: The patent portfolio value index. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 21, 174–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Sun, L.; Du, B.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J. Heterogeneous graph representation learning with relation awareness. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 5935–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yang, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Spatio-temporal knowledge graph based forest fire prediction with multi source heterogeneous data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alilu, E.; Derakhshanfard, N.; Ghaffari, A. An Adaptive Data Gathering Scheduler Based on Data Variance for Energy Efficiency in Mobile Social Networks. Int. J. Networked Distrib. Comput. 2025, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z. Recommendation of patent transaction based on attributed heterogeneous network representation learning. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2022, 41, 1214–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z. Explainable paper recommendations based on heterogeneous graph representation learning and the attention mechanism. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2024, 43, 802–817. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. A temporal evolution and fine-grained information aggregation model for citation count prediction. Scientometrics 2025, 130, 2069–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Lerner, J. Innovation and Its Discontents: How Our Broken Patent System Is Endangering Innovation and Progress, and What to Do About It; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Yoon, J. Application technology opportunity discovery from technology portfolios: Use of patent classification and collaborative filtering. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 118, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Another perspective of over-smoothing: Alleviating semantic over-smoothing in deep GNNs. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 6897–6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodley-Scott, T.; Oymak, E. Enabling an environment for transformational strategic alliances. In University–Industry Partnerships for Positive Change; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 55–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sasikala, S.; Christopher, A.B.A.; Geetha, S.; Kannan, A.; Rajkumar, R. A predictive model using improved normalized point wise mutual information (INPMI). In Proceedings of the 2013 Eleventh International Conference on ICT and Knowledge Engineering, Bangkok, Thailand, 20–22 November 2013; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rendle, S.; Freudenthaler, C.; Gantner, Z.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. BPR: Bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1205.2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, A.; Jones, C.; Madhavan, S. Patentsview: An Open Data Platform to Advance Science and Technology Policy. 2021. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3874213 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yao, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Su, Z. Arnetminer: Extraction and mining of academic social networks. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 August 2008; pp. 990–998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H. Adaptations of ROUGE and BLEU to better evaluate machine reading comprehension task. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.03578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Out; Association for Computational Linguistics: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, K.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Zhou, X. Best keyword cover search. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2014, 27, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Lightgcn: Simplifying and powering graph convolution network for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, China, 25–30 July 2020; pp. 639–648. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H. Glint-ru: Gated lightweight intelligent recurrent units for sequential recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; Volume 1, pp. 1948–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Multi-view self-supervised learning on heterogeneous graphs for recommendation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 174, 113056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X. Research on recommendation algorithm based on knowledge graph. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Intelligent Computing, Beijing, China, 26–28 January 2024; pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.H.; Yang, Z.R.; Lai, P.Y.; Wong, K.C.; Cheung, W.K. Knowledge-aware explainable reciprocal recommendation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 8636–8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z. Faithful Explainable Recommendation via Neural Logic Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM), Online, 4–8 March 2024; pp. 982–991. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, C.; Krishna, S.; Saxena, E.; Goel, A.; Saha, A.; Rudin, C. OpenXAI: Towards a Transparent Evaluation of Post-hoc Explanations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2022, 35, 15784–15799. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, S.; Lee, J. Exploring potential R&D collaboration partners using embedding of patent graph. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | InventedBy | BelongsTo | Cites | OwnedBy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | i1, i2 | c1 | - | a1 |

| 2020 | i1, i2 | c1 | p2 | a1 |

| 2021 | i1, i2 | c1 | p2, p3 | a1 |

| 2022 | i1, i2 | c1, c2 | p2, p3, p4 | a1 |

| 2023 | i1, i2 | c1, c2 | p2, p3, p4, p5 | a1 |

| 2024 | i1, i2, i3 | c1, c2 | p2, p3, p4, p5, p6 | a1 |

| Hyper-Parameter | Symbol | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Embedding Dimension | ds | 128 | Output dimension of the R-GCN layers |

| Temporal Evolution Dimension | dp | 128 | Output dimension of the Bi-LSTM layers |

| Number of Attention Heads | h | 8 | Number of heads in the multi-head attention |

| Hidden Dimension | dh | 256 | Hidden state dimension for the GFRU |

| FFN Dimension | dff | 512 | Intermediate layer dimension in the FFN |

| Temporal Window Size | L | 5 | Number of historical years to consider |

| Number of Negative Samples | K | 5 | Number of negative samples per positive instance |

| Recommendation Loss Weight | μ | 1.0 | Weight for the recommendation task loss |

| Explanation Loss Weight | ω | 0.5 | Weight for the explanation generation task loss |

| L2 Regularization Coefficient | γ | 10−5 | Strength of the L2 regularization |

| Similarity Balance Coefficient | α | 0.6 | Weight for balancing deterministic and probabilistic similarity |

| KL Divergence Temperature | λ | 0.1 | Scaling parameter for the probabilistic distance |

| Statistic | Count | Statistic | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Span | 2005–2024 | Cites Relations | 8,734,592 |

| Patents | 1,254,321 | InventedBy Relations | 3,456,789 |

| Organizations | 23,456 | BelongsTo Relations | 2,876,543 |

| Inventors | 543,210 | OwnedBy Relations | 1,123,456 |

| IPCs | 1234 | Acquired (Train) | 154,321 |

| Total Nodes | 1,822,221 | Acquired (Val/Test) | 12,345/12,345 |

| Total Edges | 16,345,701 | Sparsity | ~0% |

| Statistic | Count | Statistic | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Span | 2005–2024 | Cites Relations | 25,789,123 |

| Papers | 4,321,098 | Writes Relations | 15,432,109 |

| Authors | 5,678,901 | PublishedIn Relations | 4,321,098 |

| Organizations | 34,567 | Interactions (Train) | 12,345,678 |

| Venues | 5432 | Interactions (Val/Test) | 23,456/23,456 |

| Total Nodes | 10,040,000 | Total Edges | 45,542,330 |

| Model | HR@10 | NDCG@10 | BLEU-4 | KC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEAHG-EPR (Full Model) | 0.8542 | 0.6518 | 0.4315 | 0.7850 |

| w/o Temporal | 0.8215 | 0.6180 | 0.4290 | 0.7795 |

| w/o Uncertainty | 0.8398 | 0.6375 | 0.4308 | 0.7841 |

| w/o Attention | 0.8355 | 0.6302 | 0.4188 | 0.7652 |

| w/o Joint-Training | 0.8460 | 0.6433 | 0.3956 | 0.7104 |

| w/o Feature-Guidance | 0.8539 | 0.6515 | 0.3521 | 0.1234 |

| Model | HR@10 | NDCG@10 | HR@20 | NDCG@20 | HR@50 | NDCG@50 | BLEU-4 | ROUGE-L | KC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPR-MF | 0.4512 | 0.2845 | 0.5821 | 0.3456 | 0.7345 | 0.4123 | - | - | - |

| LightGCN | 0.7105 | 0.5011 | 0.8123 | 0.5678 | 0.9012 | 0.6234 | - | - | - |

| GLINT-RU | 0.6988 | 0.4890 | 0.7954 | 0.5501 | 0.8876 | 0.6012 | - | - | - |

| DHGPF | 0.8015 | 0.5987 | 0.8876 | 0.6543 | 0.9453 | 0.7011 | - | - | - |

| KGAT-SS | 0.8324 | 0.6278 | 0.9011 | 0.6801 | 0.9567 | 0.7256 | 0.3812 | 0.4503 | 0.1567 |

| KAERR | 0.7850 | 0.5765 | 0.8654 | 0.6321 | 0.9234 | 0.6805 | 0.3543 | 0.4321 | 0.4501 |

| TEAHG-EPR | 0.8542 | 0.6518 | 0.9156 | 0.7012 | 0.9678 | 0.7455 | 0.4315 | 0.4850 | 0.7850 |

| Model | HR@10 | NDCG@10 | BLEU-4 | ROUGE-L | KC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPR-MF | 0.3876 | 0.2311 | - | - | - |

| LightGCN | 0.6543 | 0.4532 | - | - | - |

| GLINT-RU | 0.6612 | 0.4601 | - | - | - |

| DHGPF | 0.7201 | 0.5187 | - | - | - |

| KGAT-SS | 0.7435 | 0.5378 | 0.4011 | 0.4702 | 0.1899 |

| KAERR | 0.7022 | 0.5013 | 0.3805 | 0.4565 | 0.4876 |

| TEAHG-EPR | 0.7654 | 0.5601 | 0.4523 | 0.5011 | 0.8012 |

| Explainer Method | Fidelity Score (Prob. Drop) | Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Random Selection | 0.032 | - |

| Retrieval-based (TF-IDF) | 0.152 | Baseline |

| Attention-based (KGAT-SS) | 0.285 | +87.5% |

| TEAHG-EPR (Ours) | 0.421 | +176.9% |

| Model | HR@10 | NDCG@10 | Relative Drop (vs. Full) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LightGCN | 0.2105 | 0.1532 | −69.4% |

| KGAT-SS | 0.6120 | 0.4532 | −27.8% |

| TEAHG-EPR | 0.6845 | 0.5124 | −21.4% |

| Rank | Recommended Patent | Generated Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | US 11,211,465: “Nanosheet semiconductor device and method of manufacturing the same” | “This patent is recommended because it aligns with Intel’s strategic focus on nanosheet transistor architecture. The technology, which involves vertically stacked gate-all-around FETs, is highly relevant given Intel’s recent advancements in RibbonFET and PowerVia technologies.” |

| 2 | US 11,289,397: “Hybrid bonding with improved alignment” | “We recommend this patent due to its strong relevance to hybrid bonding and advanced packaging. The proposed method for integrating HBM directly onto a logic die is a key technology, echoing Intel’s publicly stated goals in developing Foveros and EMIB chiplet integration.” |

| 3 | US 11,271,139: “Methods for monolithic integration of quantum dot light emitting diodes on silicon” | “This recommendation points to a potential new frontier: silicon photonics. The patent describes a method for integrating quantum dot emitters, which is highly relevant for future optical interconnects. This aligns with a potential long-term strategic direction for overcoming data transfer bottlenecks.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, K.-W. Navigating Technological Frontiers: Explainable Patent Recommendation with Temporal Dynamics and Uncertainty Modeling. Symmetry 2026, 18, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010078

Huang K-W. Navigating Technological Frontiers: Explainable Patent Recommendation with Temporal Dynamics and Uncertainty Modeling. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Kuan-Wei. 2026. "Navigating Technological Frontiers: Explainable Patent Recommendation with Temporal Dynamics and Uncertainty Modeling" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010078

APA StyleHuang, K.-W. (2026). Navigating Technological Frontiers: Explainable Patent Recommendation with Temporal Dynamics and Uncertainty Modeling. Symmetry, 18(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010078