Symmetrical Rock Fractures Based on Valley Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

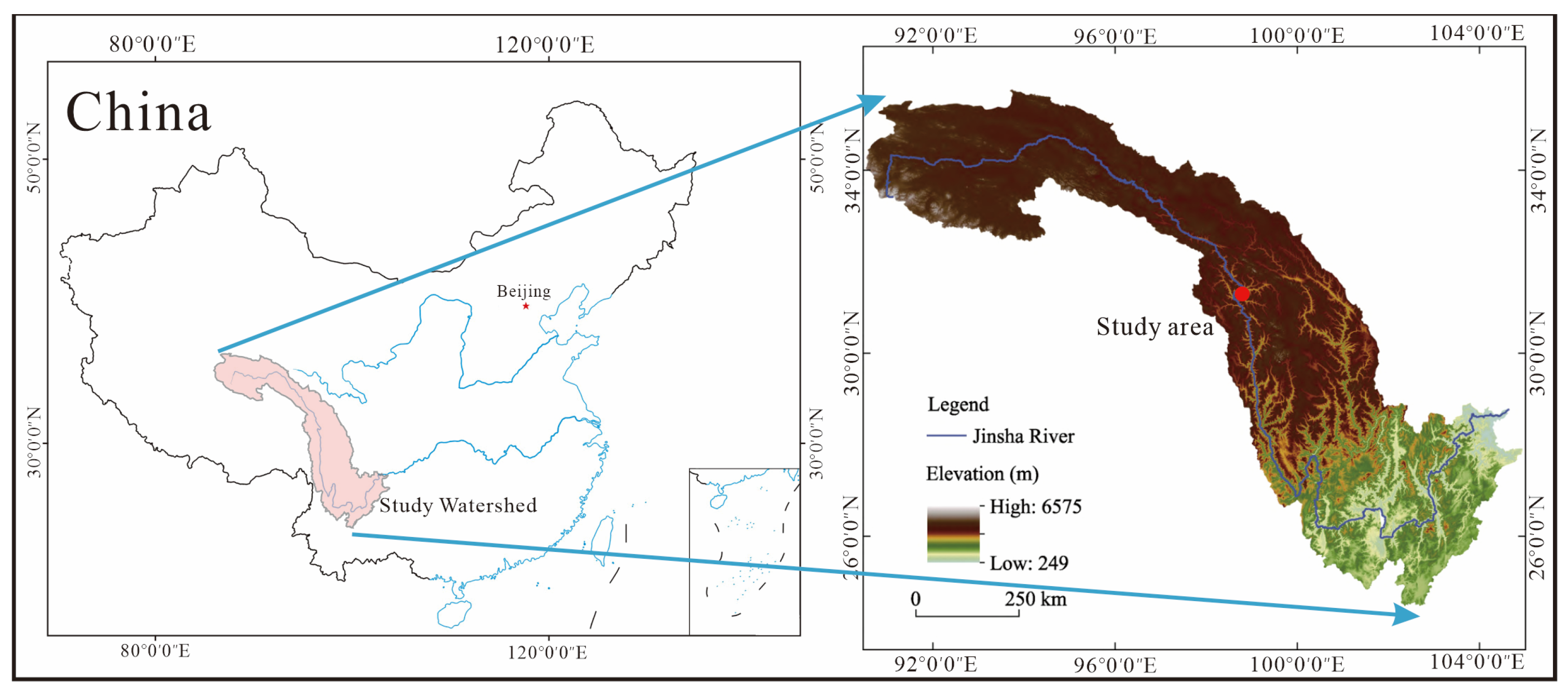

2. Engineering Geological Conditions

3. Characteristics of Deep-Seated Fracturing

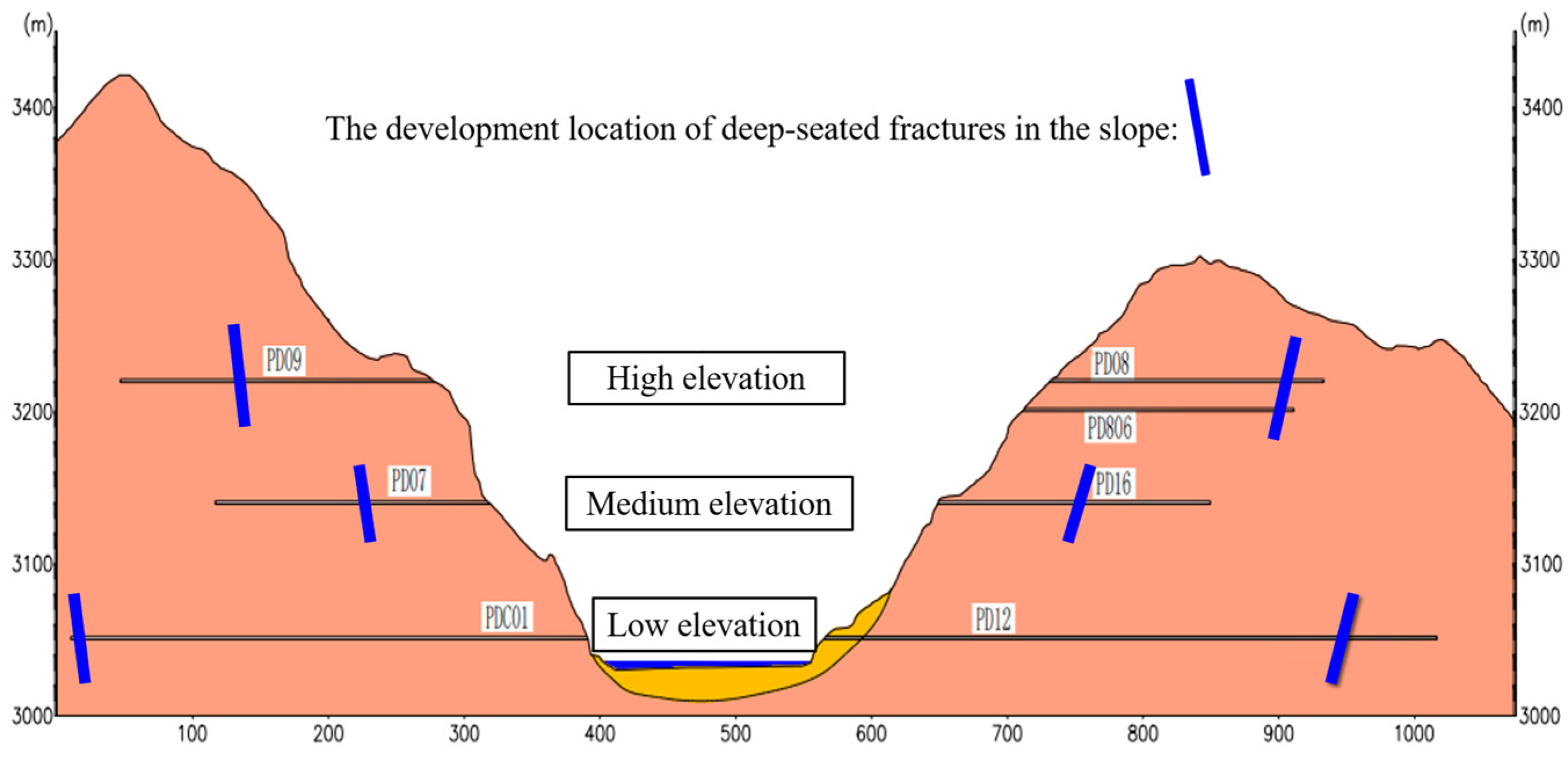

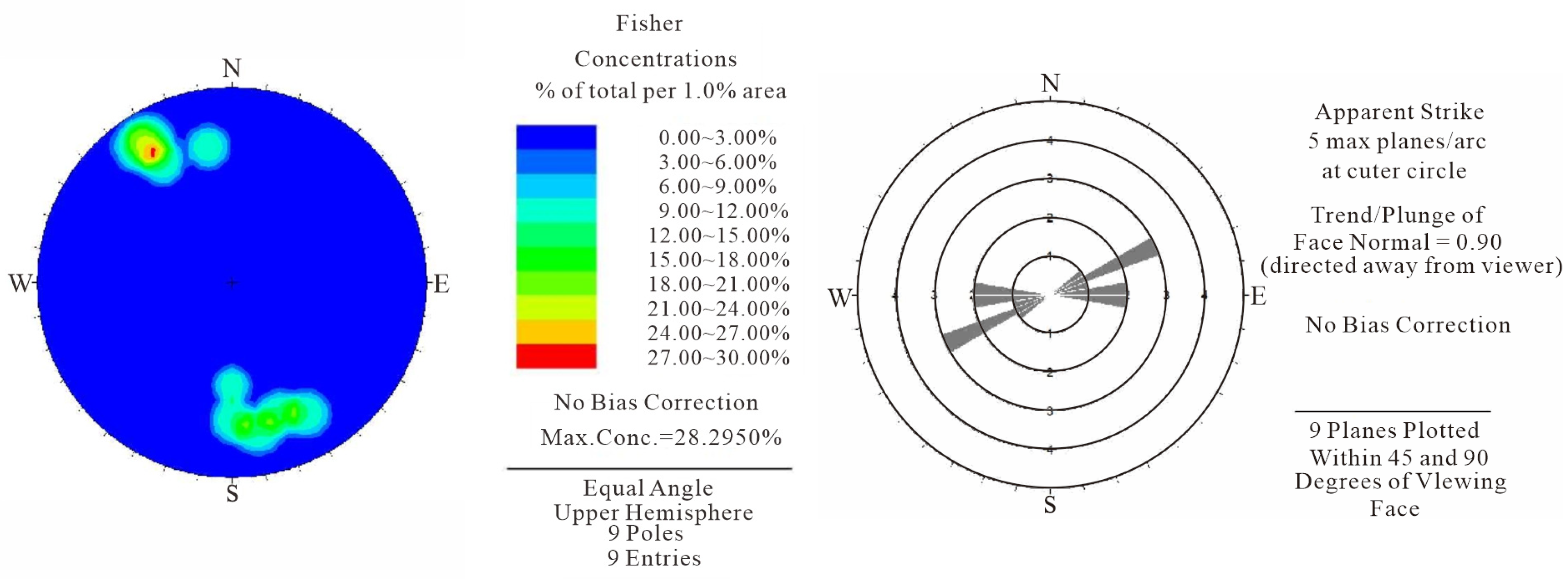

3.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics

3.2. Morphological and Material Characteristics

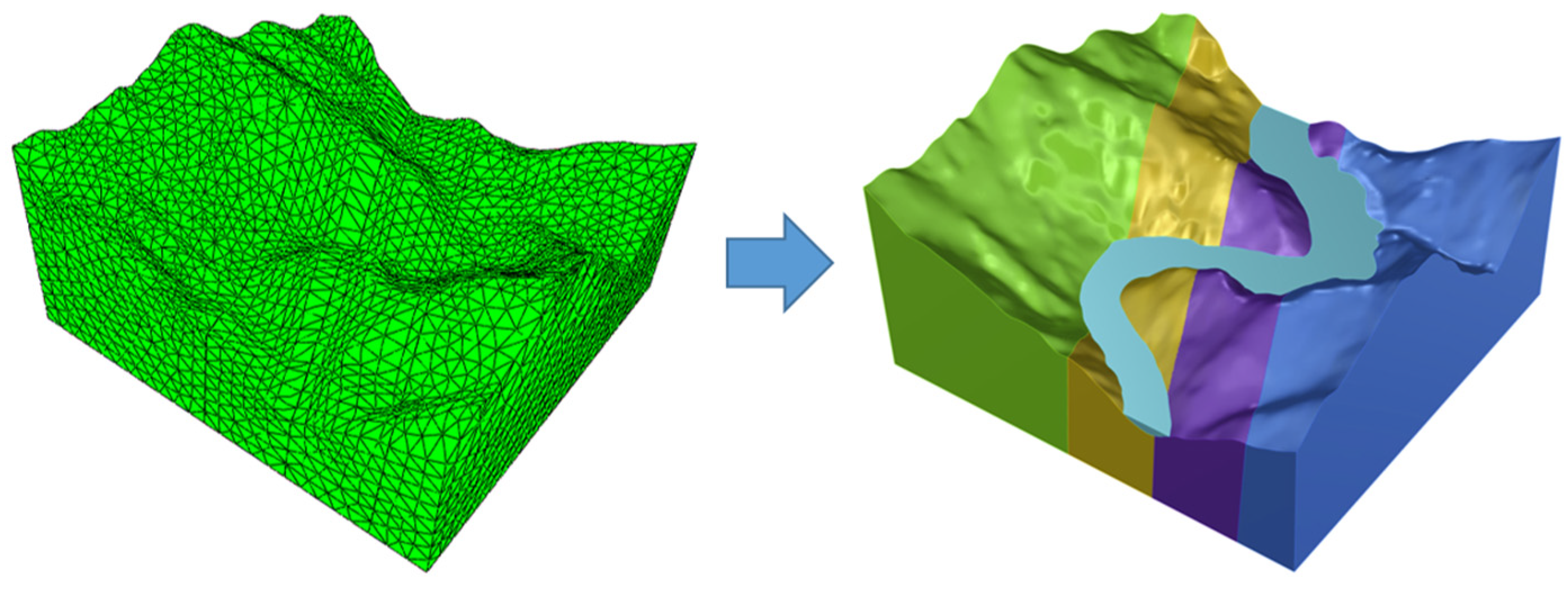

4. Valley Evolution Numerical Modeling

4.1. Valley Incision Evolution

4.2. Establish a Numerical Model

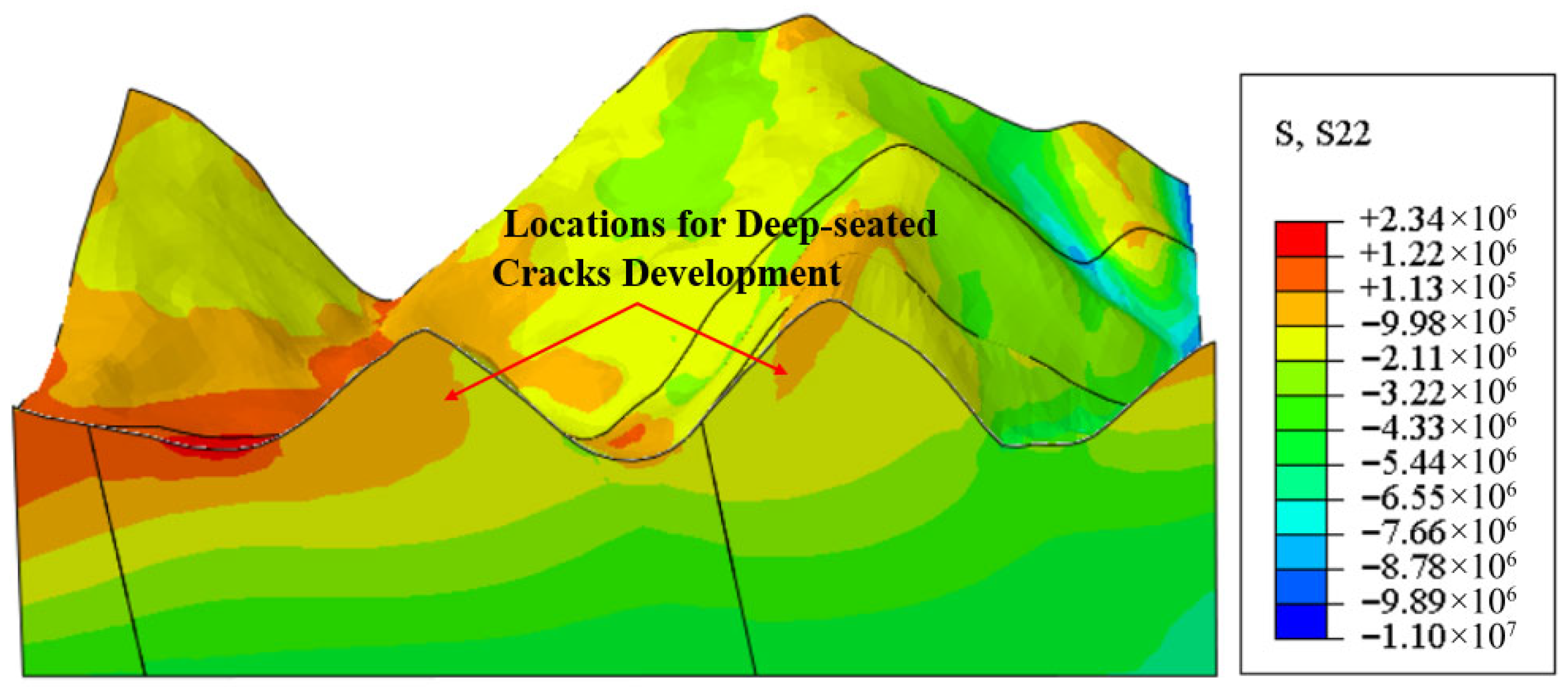

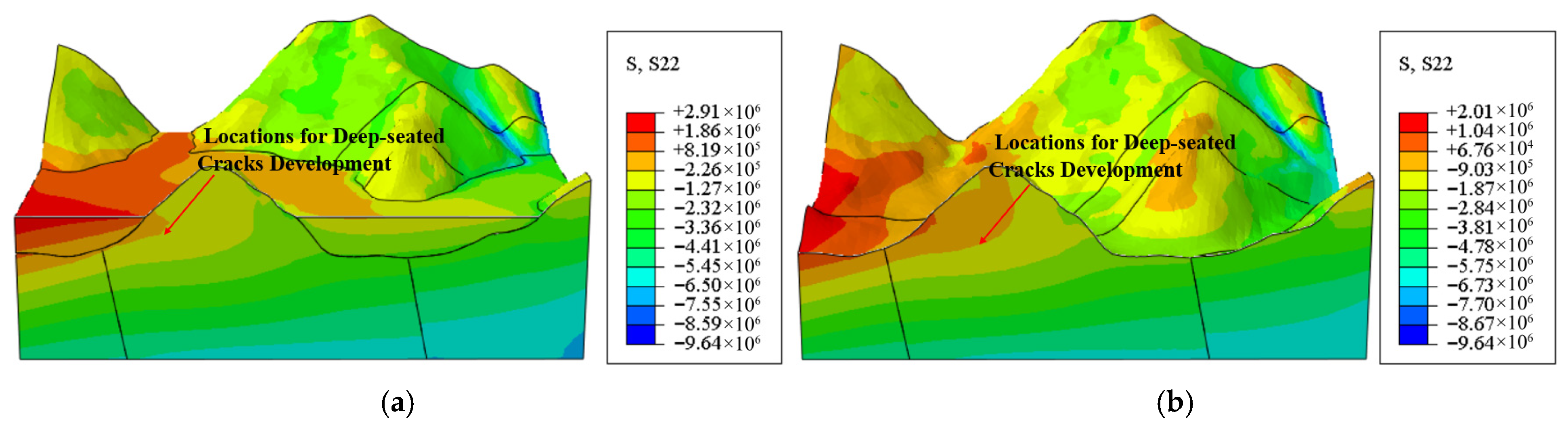

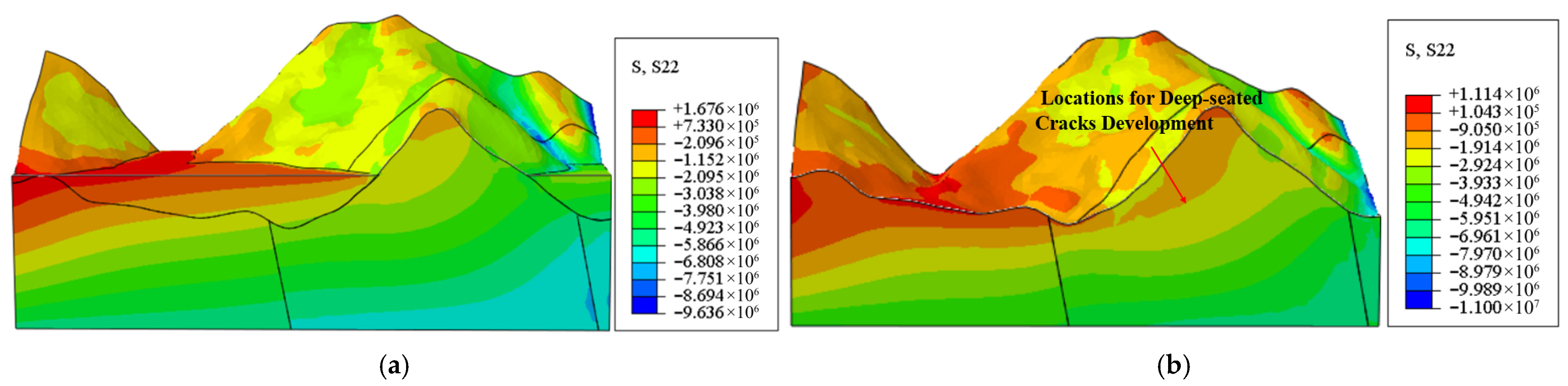

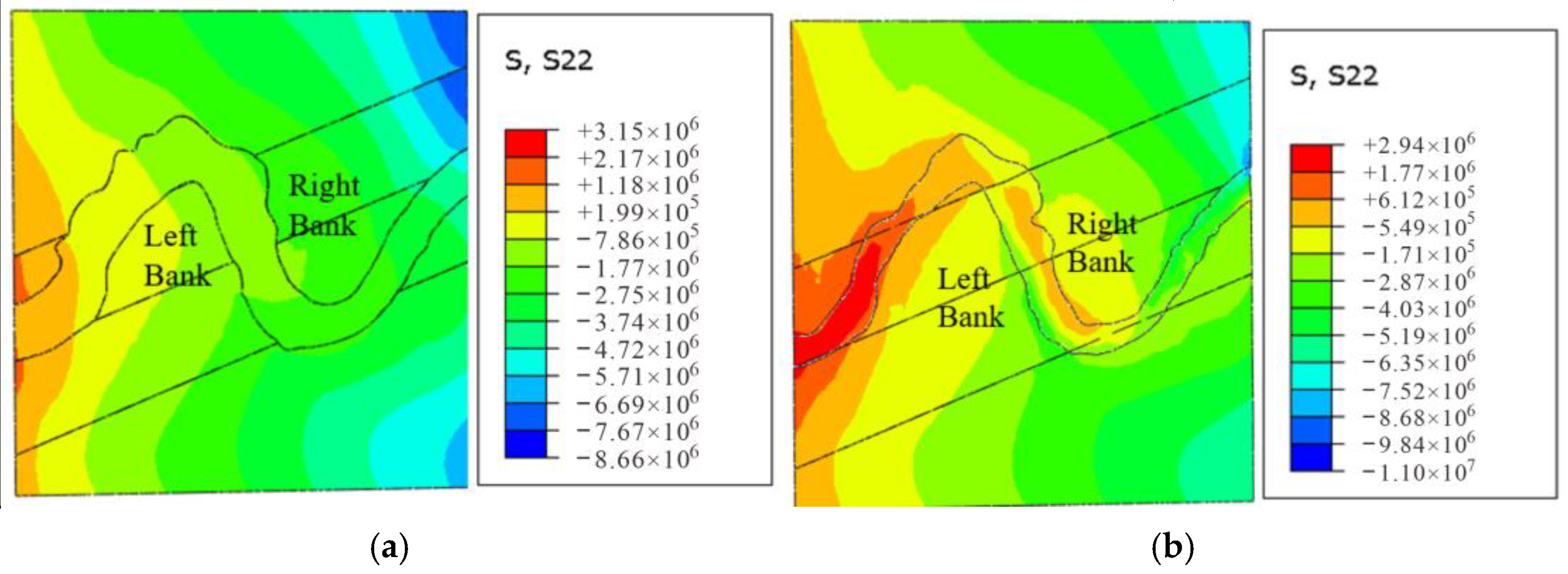

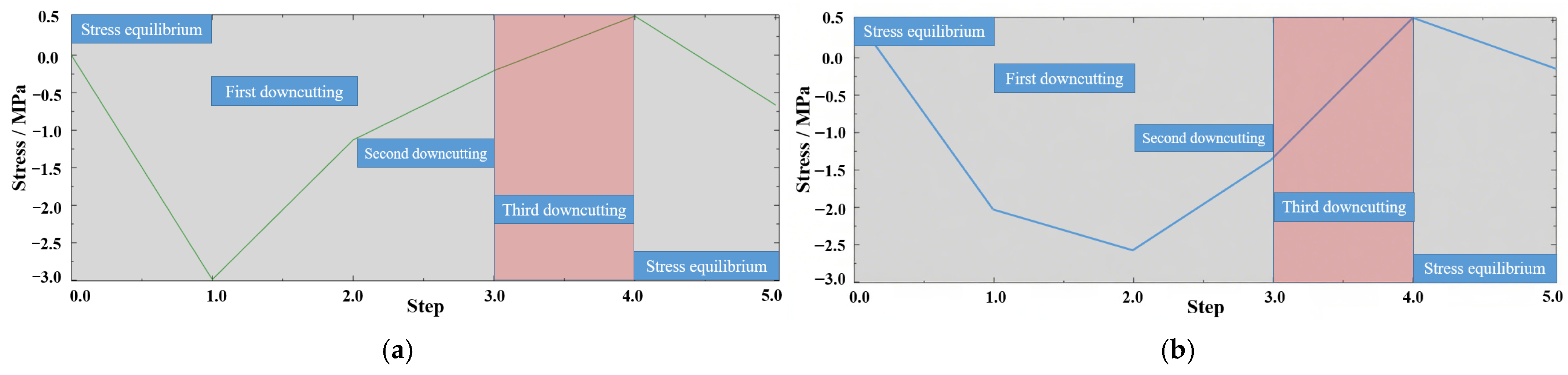

4.3. Analysis of Simulation Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sissakian, V.K.; Adamo, N.; Al-Ansari, N. The Role of Geological Investigations for Dam Siting: Mosul Dam a Case Study. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 2085–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Połomski, M.; Wiatkowski, M.; Ługowska, G. Comparative Analysis of Studies of Geological Conditions at the Planning and Construction Stage of Dam Reservoirs: A Case Study of New Facilities in South-Western Poland. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.X.; Xu, Y.J.; Jin, F.; Wang, J.T. Seismic stability assessment of an arch dam-foundation system. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2015, 14, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, D.; Chala, E.T.; Jilo, N.Z.; Garo, T. Engineering Geological Investigation of the Katar Dam Foundation and Abutment Slope Stability Analysis, Southeast Ethiopia. Indian Geotech. J. 2025, 55, 1563–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, L.; Meten, M.; Garo, T. Leakage and abutment slope stability analysis of Arjo Didesa dam site, western Ethiopia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.W.; Wu, F.Q.; Lan, H.X. Study on the mechanism of the deep fractures of the left abutment slope at the Jinping First Stage Hydropower Station. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2002, 24, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Zhu, H.C.; Wang, S.J. Primary research on mechanism of deep fractures formation in left bank of Jinping First Stage Hydropower Station. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2008, 27, 2855–2863. Available online: https://rockmech.whrsm.ac.cn/CN/abstract/abstract24314.shtml (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Huang, R.Q.; Lin, F.; Chen, D.J.; Wang, J.H. Study on the formation of rocky high slope unloading zone and its engineering properties. J. Eng. Geol. 2001, 3, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, Q.H.; Chen, W.D. Analysis on the genetic mechanism of deep cracks in the right bank of the reservoir head area at Pubugou Hydropower Station. J. Eng. Geol. 2005, 3, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.F.; Qi, S.W.; Teng, K.Y.; Long, X. Spectial characteristics of deep fractures in high and steep slopes in southwestern of China. J. Eng. Geol. 2007, 6, 730–738. Available online: http://www.gcdz.org/article/id/8836 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Dagdelenler, G. Impact of Rock Mass Strength Anisotropy with Depth on Slope Stability Under Excavation Disturbance. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangerl, C.; Koppensteiner, M.; Strauhal, T. Semiautomated Statistical Discontinuity Analyses from Scanline Data of Fractured Rock Masses. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosta, G.B.; Frattini, P.; Agliardi, F. Deep seated gravitational slope deformations in the European Alps. Tectonophysics 2013, 605, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hradecký, J.; Pánek, T. Deep-seated gravitational slope deformations and their influence on consequence mass movements (case studies from the highest part of the Czech Carpathians). Nat. Hazards 2008, 45, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Dyskin, A.; Dight, P.; Pasternak, E.; Hsieh, A. Review of unloading tests of dynamic rock failure in compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 225, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhao, Q.H.; Peng, S.Q. In-situ stress field evolution of deep fracture rock mass at dam area of Baihetan hydropower station. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Wang, L.S.; Shen, J.H.; Xu, J. Disquisition on distributing law of bank slope deep fracture of an electricity station dam site section at southwest. J. Chongqing Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2003, 26, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.W.; Wu, F.Q.; Yan, F.Z.; Lan, H.X. Mechanism of deep cracks in the left bank slope of Jinping first stage hydropower station. Eng. Geol. 2004, 73, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.W.; Feng, X.M.; Xiang, B.Y.; Xing, W.B.; Zeng, Y. Research on key technologies for high and steep rock slopes of hydropower engineering in Southwest China. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2011, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. A Study on the Formation Mechanism and Engineering Effects of Deep Crack in Typical Slopes of Middle and Lower Research of the Dadu River. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.F.; Zhao, Q.H.; Deng, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.Q. Development characteristics of deep fracture rock mass of Yebatan high arch dam and its stability influence analysis. Yangtze River 2024, 55, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, G.X.; Deng, H. Unloading depth of rock masses and its relations with river downcutting in deep valleys in Southwest China. Eng. Geol. 2021, 288, 106161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Zhang, K.K.; Yan, C.G.; Lan, H.X.; Wu, F.Q.; Zheng, H. Excavation damaged zone division and time-dependency deformation prediction: A case study of excavated rock mass at Xiaowan Hydropower Station. Eng. Geol. 2020, 272, 105668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, N.; Eberhardt, E.; Bustin, R.M. Investigation of the influence of natural fractures and in situ stress on hydraulic fracture propagation using a distinct-element approach. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 52, 926–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, R.; Coggan, J.; Flynn, Z.; Elmo, D. The Development of a new Numerical Modelling Approach for Naturally Fractured Rock Masses. Rock Mech. Rock Engng. 2006, 39, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Yang, D.Y.; Li, L.P.; Shi, A.C.; Lu, F.; Ge, Z.S.; Xu, Q.M. Preliminary study on the downcut rate of the Baihetan section of the Jinsha River. Quat. Sci. 2010, 30, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.C.; Guo, X.J.; Chen, H. Analysis on geomorphological characteristics of catchments and its influencing factors in Dege-Baiyu section of the upper Jinsha River. Quat. Sci. 2023, 45, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, E.Z.; Liu, S.G. Study of evolutional simulation of Baihetan river valley and evaluation of engineering quality of jointed basalt P2β3. Rock Soil Mech. 2009, 30, 3013–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.Y.; Zhuang, W.Y.; Wang, T.; Gao, Z.F.; Liu, Y.R.; Yang, Q. Formation mechanism of deep fractures in near-dam slope of Jinping I Hydropower Station and their influence on long-term slope deformation. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2024, 64, 1944–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, V.H.; Go, G.H. A novel approach to stability analysis of random soil-rock mixture slopes using finite element method in ABAQUS. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 14381–14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, A.V.R.; Manideep, R.; Chavda, J.T. Sensitivity analysis of slope stability using finite element method. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, M.R.; Zakeri, A.; Bahmani Shoorijeh, M. Using Finite Element Strength Reduction Method for Stability Analysis of Geocell-Reinforced Slopes. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2019, 37, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, W.; Niu, Q.; Wei, H. An Experimental Investigation on Mechanical Properties and Failure Characteristics of Layered Rock Mass. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H. Anisotropy of deformation parameters of stratified rock mass. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Dang, F. Numerical Analysis of Instability Mechanism of a High Slope under Excavation Unloading and Rainfall. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.H.; Wang, L.S.; Wang, Q.H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, Y.S.; Sun, B.J. Deformation and fracture features of unloading rock mass. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2003, 22, 2028–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Yin, X.T.; Tang, H.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, H. Method of Stress Field and Stability Analysis of Bedding Rock Slope Considering Excavation Unloading. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 4205–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Tang, H.; Qin, H.; Wu, Z.J.; Xie, Y.C. Stress field and stability calculation method for unloading slope considering the influence of terrain. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Leng, X.L.; Zhang, Z.R.; Yang, C.; Chen, J. Numerical study on failure path of rock slope induced by multi-stage excavation unloading based on crack propagation. Rock Soil Mech. 2023, 44, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Y.L. Study of Unloading Relaxation for Excavation Based on Unbalanced Force and Its Application in Baihetan Arch Dam. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 1819–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Chen, J.; Cai, J. Deformation monitoring of rock slope with weak bedding structural plane subject to tunnel excavation. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Zhou, Z.H.; Dou, W.; Chen, Z.H. Theoretical unloading fracture mechanism and stability analysis of the slope rock masses in open-pit mines. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2274810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adit Number | Elevation of Adit Entrance (m) | Depth (m) | Attitude | Fracture Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDC01 | 3050 | 180 | N80°E/NW∠75° | Fractures typically exhibit apertures of 1–2 cm (maximum 4 cm), with localized voids containing infilled rock blocks and angular gravel. Secondary clay partially fills some sections, appearing in dry conditions. Fracture surfaces display moderate to strong iron oxide staining, within fracture zones measuring 5–20 cm in width. |

| PDC01 | 3050 | 400 | N60°E/SE∠80° | Fracture zones measure 1–1.5 m in width, traversing fractured rock masses exhibiting mosaic–cataclastic textures. Fractures within these zones display apertures of 1–2 cm (locally widening to 3–5 cm), with fracture surfaces showing localized moderate iron oxide staining and partially filled by calcite veins under dry conditions. |

| PDC01 branch adit | 3050 | 410 | EW/S∠55° | Fractures exhibit apertures of 3–5 cm, containing infilled rock blocks and angular gravel with prominent voids, while displaying slight iron oxide staining on dry fracture surfaces. |

| PD12 | 3050 | 380 | N75°E/NW∠85° | These fractures typically exhibit apertures of 5–7 cm (maximum 10 cm), with localized voids containing infilled rock blocks and angular gravel. |

| PD16 | 3141 | 102 | N80°W/SW∠65–85° | These fractures typically display apertures of 5–10 cm (locally reaching 20–40 cm), infilled with rock blocks, angular gravel, rock fragments, and secondary clay, forming visible cavities extending approximately 3 m in depth under damp conditions. |

| PD07 | 3130 | 80 | N73°E/NW∠82° | These fractures typically exhibit apertures of 3–5 cm with undulating, rough surfaces displaying strong iron oxide staining, infilled with calcium coatings and rock fragments under dry conditions. |

| PD08 | 3231 | 173 | N70°E/SE∠70° | These fractures exhibit apertures of 10–20 cm (locally reaching 30 cm), containing minor amounts of rock blocks and angular gravel with prominent voids, while displaying moderate iron oxide staining on fracture surfaces. |

| PD09 | 3221 | 142 | N60°E/NW∠70° | Extending over 5 m in length, these fractures exhibit rough surfaces with strong iron oxide staining, display apertures of 10–20 cm, and are infilled with calcareous fine gravel under dry conditions. |

| PD806 | 3203 | 180 | N64°W/NE∠72° | These fractures typically exhibit apertures of 5–30 cm (locally up to 60 cm), are infilled with rock blocks and rock fragments, display moderate iron oxide staining on fracture surfaces, and feature calcite cementation. |

| Period | Signature Landform Types | Altitude (m) | Absolute Age (Ma) | Geological Time | Downcutting Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wide valley | Grade Ⅶ terrace | 3450 | 2.05 ± 0.12 | Q1 | 1.0 mm/a |

| Wide valley~Gorge | Grade Ⅵ terrace | 3353 | 1.57 ± 0.21 | Q1 | 1.5 mm/a |

| Gorge | Grade Ⅴ terrace | 3196 | 0.45 ± 0.013 | Q2 | average downcutting rate: 3 mm/a |

| Grade Ⅳ terrace | 3116 | 0.21 ± 0.002 | Q2 | ||

| Grade Ⅲ terrace | 3051 | 0.07 ± 0.008 | Q3 | ||

| Grade Ⅱ terrace | 3040 | 0.025 ± 0.001 | Q3 | ||

| Grade Ⅰ terrace | 3030 | 0.006 ± 0.0002 | Q4 |

| Rock Layers | Deformation Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Dry Density (103 kg/m3) | Internal Friction Angle | Cohesion (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | 0.25 | 2.70 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 10 | 0.27 | 2.68 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 15 | 0.25 | 2.70 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 12 | 0.26 | 2.68 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, X.; Ma, H.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, D. Symmetrical Rock Fractures Based on Valley Evolution. Symmetry 2026, 18, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010006

Wei X, Ma H, Wu Z, Zheng D. Symmetrical Rock Fractures Based on Valley Evolution. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Xingyu, Hong Ma, Zhanglei Wu, and Da Zheng. 2026. "Symmetrical Rock Fractures Based on Valley Evolution" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010006

APA StyleWei, X., Ma, H., Wu, Z., & Zheng, D. (2026). Symmetrical Rock Fractures Based on Valley Evolution. Symmetry, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010006