1. Introduction

Object detection, as a core task in computer vision, plays a pivotal role in applications such as autonomous driving, intelligent surveillance, and robotic navigation. With the rapid development of deep learning, CNN-based and ViT-based detectors have achieved remarkable advances in both accuracy and efficiency [

1,

2]. However, most existing detection methods rely on visible images and therefore suffer from severe performance degradation under low illumination, nighttime, or adverse weather conditions [

3,

4]. When ambient lighting changes drastically or is heavily influenced by haze, smoke, or dust, the texture and color cues in visible images are significantly degraded, leading to blurred object boundaries and reduced detection confidence, which in turn undermines the robustness and practicality of the system [

5]. Infrared images capture thermal radiation emitted by objects and are inherently insensitive to illumination changes, while also exhibiting strong penetration capabilities. As a result, they can maintain stable image quality at night and in harsh environments [

6]. Nevertheless, infrared images usually lack rich texture details and semantic information, making it difficult to distinguish targets with similar temperatures or objects with similar shapes. Therefore, a single-modality vision system is inadequate for achieving stable and reliable object perception in complex, dynamically changing real-world scenarios. By merging infrared and visible information, one can achieve complementary advantages at both the energy and semantic levels, thereby enabling more comprehensive and robust environmental perception. This has become an important research direction in multimodal object detection [

7,

8]. More broadly, multi-sensor data integration with machine learning has been successfully explored in various domains beyond object detection, further underscoring the versatility and application potential of multimodal perception frameworks [

9,

10].

Existing infrared and visible fusion-based detection methods can be broadly categorized into three types: pixel-level fusion, feature-level fusion, and decision-level fusion [

11,

12]. Feature-level fusion has become the main solution [

13,

14,

15]. In recent years, researchers have further improved fusion-based detection by introducing attention mechanisms, cross-modal Transformers, and dynamically learned fusion weights [

16,

17]. Despite these advances, multimodal fusion detection still faces several key challenges:

(1) Insufficient modeling of modality-specific characteristics. Most existing approaches adopt symmetric network architectures, using identical or similar feature extractors for the infrared and visible branches, without fully considering the fundamental differences between the two modalities in imaging mechanisms, information density, and semantic expressiveness. Such designs limit the effective exploitation of information specific to each modality.

(2) Lack of adaptivity in the fusion mechanism. Many fusion strategies rely on fixed weights or simple feature concatenation, making it difficult to adaptively adjust the fusion behavior according to scene content, object properties, and modality quality. This often leads to redundancy of features, noise interference, and a mismatch of modality in complex scenarios, compromising the stability of the detection performance.

(3) Underutilization of frequency-domain information. Existing studies mainly focus on spatial-domain feature fusion, while overlooking the complementary properties of infrared and visible images in the frequency domain. The low-frequency components of the infrared images highlight the global distribution of the thermal targets, whereas the high-frequency components of the visible images contain rich edge and texture details. How to effectively combine frequency- and spatial-domain features to realize cross-modal spectral complementarity remains a crucial open problem.

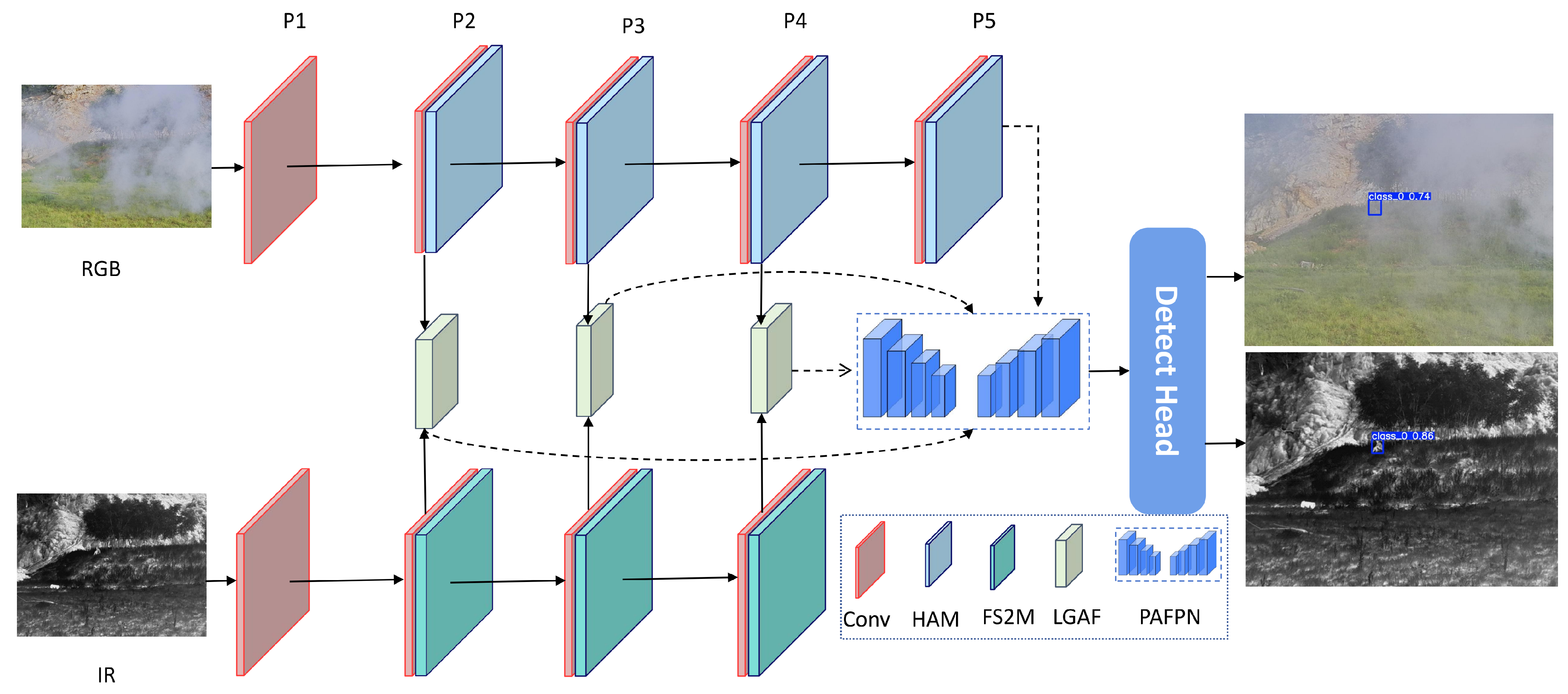

To tackle the above challenges, we propose an asymmetric spatial–frequency fusion network, AsyFusionNet, which systematically addresses key technical issues in multimodal detection through innovative network architecture and fusion mechanisms. As shown in

Figure 1a, traditional methods typically adopt a fully symmetric dual-branch structure, where the corresponding P3–P5 feature maps of the visible (RGB) and infrared (IR) branches are fused layer by layer using a generic fusion operator

F, and then jointly fed into the subsequent Neck and Head modules. Although such a design is structurally concise, it ignores the intrinsic differences in information density and semantic representation between the two modalities, leading to wasted computational resources and limited feature representation capacity.

Unlike these approaches, our model does not simply plug additional attention or frequency blocks into an existing symmetric architecture, but instead redesigns both the backbone and the fusion pipeline to explicitly encode asymmetry between RGB and IR modalities and to unify spatial- and frequency-domain interactions within a single framework, as shown in

Figure 1b. The RGB branch maintains a complete P1–P5 feature pyramid so that rich texture and semantic cues can be fully extracted, while the IR branch is only extended to the P4 level, which cuts down redundant deep-layer computation but still preserves key thermal radiation information. The RGB branch focuses on learning deeper texture and semantic representations, whereas the IR branch concentrates on shallow structures and thermal target cues; their features are dynamically fused across multiple levels to combine detailed information with high-level semantics.

On top of the above asymmetric design, AsyFusionNet employs three key components, the local–global attention fusion (LGAF) module, the hierarchical attention module (HAM), and the fourier spatial spectral modulation (FS2M) module, to accomplish multimodal feature extraction and efficient information interaction. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

Propose an asymmetric spatial–frequency fusion network, AsyFusionNet, in which the RGB branch is extended to P5 and the IR branch to P4, and hierarchically coupled fusion is performed at P2–P4. This design reduces the overall computational cost compared with symmetric backbones and simple concatenation, without sacrificing accuracy, while better reflecting the imaging characteristics of the two modalities and enhancing feature complementarity.

Design the LGAF module, which concatenates the local attention branch, the global attention branch, and the baseline feature branch, and then uses lightweight convolutions for compact spatial–channel coupling modeling. Compared with fusion strategies that rely on fixed weights or straightforward concatenation, LGAF, with almost no extra computation, significantly improves texture fidelity and semantic consistency, while effectively suppressing noise and redundant information.

Complementary feature enhancement for RGB and IR via HAM and FS2M. For visible features, we propose the HAM module, which performs dynamic kernel selection and cross-layer information sharing to enhance feature extraction. For IR features, we propose FS2M, which jointly models information in the frequency, spatial, and spectral domains to strengthen low-frequency energy and thermal target saliency. Working in tandem, HAM and FS2M make it easier for the model to distinguish small objects from large-scale scenes under low-resolution or cluttered backgrounds.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 details the network architecture of AsyFusionNet and its main components.

Section 4 reports experimental results and analysis.

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

3. Methodologies

3.1. Overall Structure

The overall architecture of AsyFusionNet is illustrated in

Figure 2. The model adopts a lightweight dual-branch asymmetric fusion framework, designed to fully exploit the complementary properties of visible (RGB) and infrared (IR) images for object detection. Given paired RGB and IR images as inputs, two independent backbone networks are used for feature extraction. In the RGB branch, HAM is employed to extract salient features from levels P1–P5, adaptively enhancing task-relevant information while suppressing background clutter, thereby highlighting structural details and semantic cues in well-illuminated regions. In parallel, the IR branch uses FS2M to extract features from P1–P4, modeling the spatial- and frequency-domain distributions of thermal radiation patterns. This enables cross-modal consistency adjustment and information compensation, and strengthens the representation of regions with weak textures or low contrast.

Subsequently, features from the two branches are fed into the LGAF module for deep fusion. By jointly integrating local details and global contextual information, LGAF effectively captures multi-scale semantic correlations, thereby improving the complementary representation and spatial alignment of cross-modal features. The fused features are then passed to a PAFPN for multi-scale feature reconstruction and semantic enhancement. Finally, the detection head operates on the enhanced feature pyramid to produce the fused detection results, accomplishing multimodal object detection under both RGB and IR imaging conditions.

3.2. Local–Global Attention Fusion (LGAF)

In RGB–IR image fusion, the features from the two modalities differ significantly, and their representations in feature space are often strongly misaligned due to discrepancies in imaging mechanisms and semantic distributions. As a result, it is difficult for fusion models to strike a balance between preserving fine details and enhancing target saliency. Moreover, in CNN-based fusion methods, the receptive field of convolution operations is inherently limited, making it hard to capture long-range contextual dependencies. Purely global attention, on the other hand, tends to overlook local structural details, and thus cannot simultaneously preserve local cues and global semantics. In addition, during multimodal feature fusion, features at different scales are often insufficiently coupled along the spatial and channel dimensions, which leads to low fusion efficiency. Most existing methods also rely on fixed weights or simple concatenation, and therefore cannot dynamically adjust the importance of each modality according to local content, making them prone to noise and redundant information. Furthermore, many existing local–global or dual-path attention mechanisms either apply local and global attention sequentially or share a single attention map across modalities, which limits their ability to decouple local and global modeling from cross-modal fusion and to provide a stable modality-agnostic reference path.

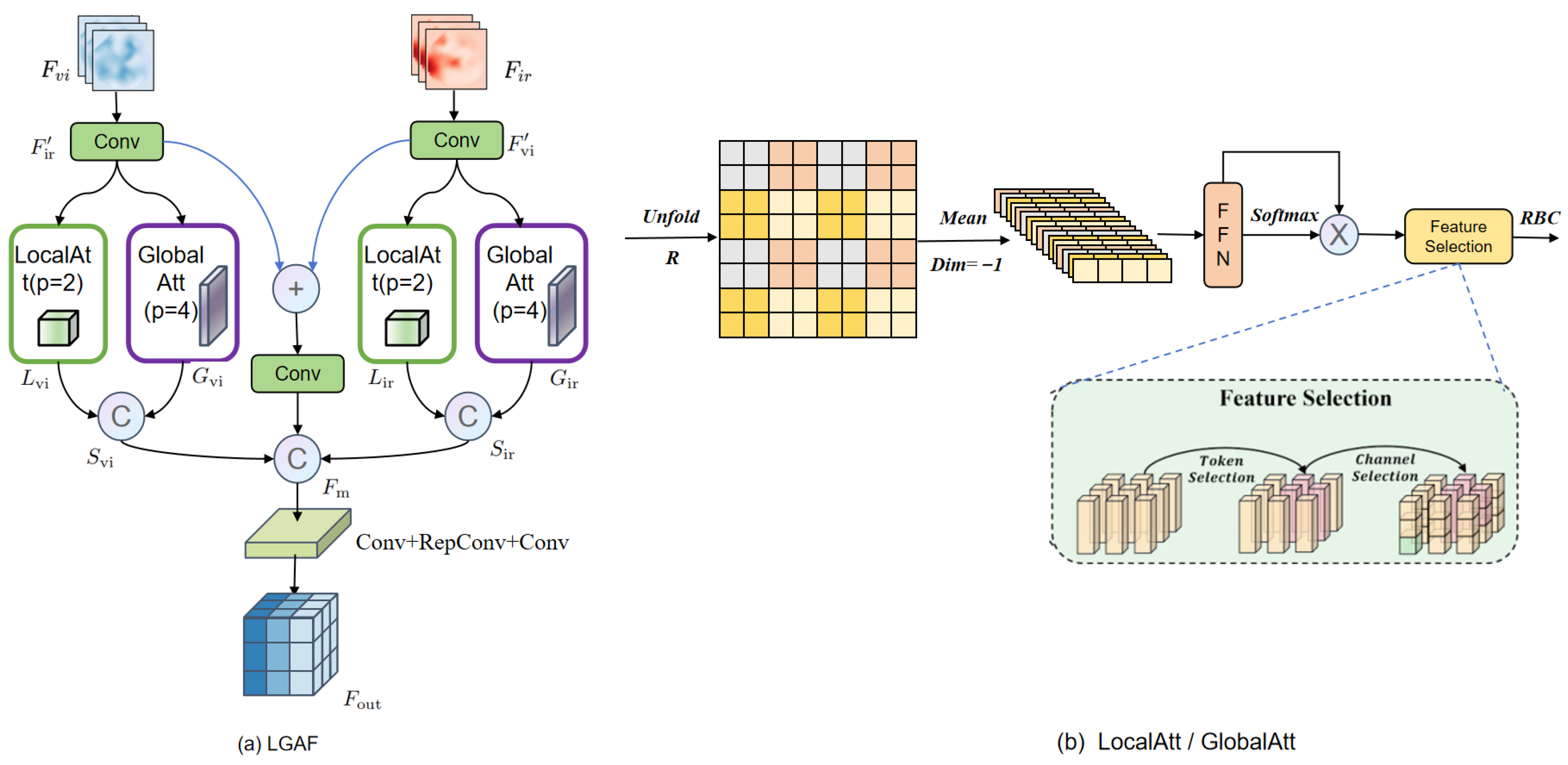

To address the above limitations in a unified manner, we propose LGAF, as shown in

Figure 3, which aims to jointly model local details and global semantic information, thereby alleviating discrepancies between RGB and IR features in terms of spatial distribution and semantic representation. In contrast to conventional local–global attention blocks, LGAF first builds modality-specific local and global responses and then performs cross-modal fusion around an explicit baseline branch, so that scale modeling and modality interaction are cleanly separated. Both the local attention (LocalAtt) and global attention (GlobalAtt) branches are built upon the parallelized patch-aware attention (PPA) module adopted in HCF-Net [

46]. Let the RGB and IR input features be denoted respectively as:

First, a

convolution is applied to align and compress the feature channels:

After obtaining the aligned RGB and IR features, we feed them into two parallel branches: LocalAtt and GlobalAtt. The local branch

adopts a smaller patch size

to model neighborhood dependencies and preserve fine details and edges. The global branch

uses a larger patch size

to capture long-range dependencies, global semantics, and saliency. The outputs of the two branches are then concatenated and fused by a convolution layer, yielding a complementary representation that is both fine-grained and globally coherent, and alleviating the bias caused by using only local or only global modeling:

The outputs of the two branches are then concatenated and fused by a convolution layer, yielding a complementary representation that is both fine-grained and globally coherent, and mitigating the bias caused by using only local or only global modeling. Subsequently, the local and global responses of each modality are first aggregated within each modality, so that the single-modal representation already exhibits multi-scale consistency, thereby avoiding information conflicts caused by scale mismatch during direct cross-modal interaction.

Next, an element-wise summation is applied to obtain a baseline cross-modal common feature, which is further refined by a

convolution for local mixing and denoising. This branch serves as a stable alignment anchor, reducing the dependence and sensitivity of the subsequent fusion process to the attention branches.

After that, the three types of features are concatenated to form a representation pool that is complementary while keeping redundancy under control, where the shared-information channel is explicitly preserved to facilitate selective emphasis on either fine details or saliency in the subsequent reorganization step:

Finally, feature reassembly and mapping are performed to produce the fused output:

This reconstruction pathway relies only on a small number of lightweight convolutions, and thus introduces merely a minor increase in FLOPs while enhancing information selection and feature recombination capabilities and maintaining good computational efficiency and deployability. As a result, the fused output preserves the structural details of the visible modality while strengthening the saliency of infrared targets, yielding a structurally consistent, semantically complete, and visually natural fusion effect.

3.3. Hierarchical Adaptive Mixer (HAM)

In multimodal image fusion, visible images play a key role in providing structured details and rich textures. However, the features of visible images are highly complex and dynamic, as they are strongly affected by illumination changes, occlusions, noise, and multi-scale structural variations. CNN-based models typically rely on fixed, static parameters, which makes it difficult to fully model multi-scale patterns when dealing with inputs exhibiting large-scale differences and complex spatial variations. The use of fixed-size convolution kernels constrains the balance between fine detail preservation and global context modeling, rendering the network sensitive to scale changes and lacking flexibility. In addition, feature maps from different layers contain complementary information: shallow layers emphasize texture and edge details, while deeper layers encode more semantic cues. Due to insufficient mechanisms for cross-layer interaction, traditional networks often fail to achieve effective collaboration among multi-level features, which in turn hampers semantic propagation between lower and higher layers. On the other hand, rigid convolutional structures introduce parameter and computation redundancy, reducing efficiency in large-scale scenarios and limiting their applicability to real-time tasks.

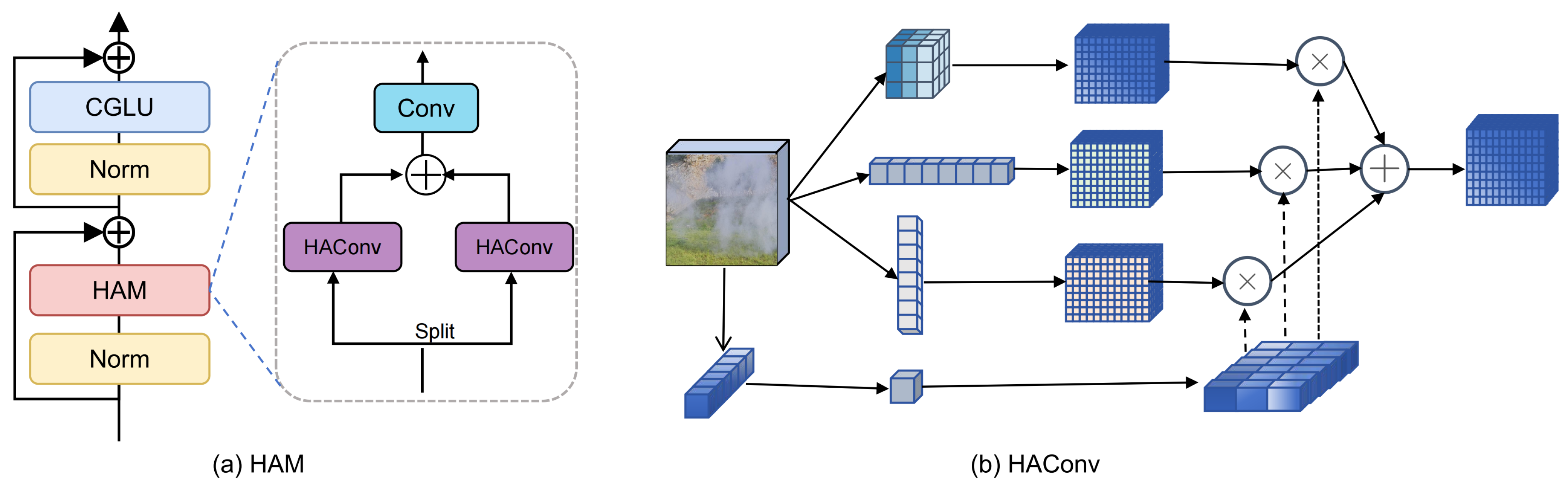

To overcome these limitations, we propose the HAM module, which aims to realize dynamic kernel selection, cross-scale feature fusion, and inter-layer information sharing, thereby forming a flexible and efficient feature extraction framework. As shown in

Figure 4a, HAM consists of a normalization layer, a context-gated linear unit (CGLU), and a core hierarchical adaptive convolution (HAConv) unit. Residual connections and hierarchical feature fusion are employed inside the module so that high-level semantic context can be injected while preserving low-level structural information, leading to robust cross-layer feature representations.

HAConv is the core component of HAM, and its structure is illustrated in

Figure 4b. Given an input feature

, we first split it into several parallel branches, and each branch applies a convolution kernel

with a different receptive field to extract features:

To adaptively select the most suitable convolution kernels according to the input features, HAM introduces a dynamic kernel weighting mechanism. Specifically, global statistics of the input are first obtained via global average pooling (GAP), and then passed through two

convolution layers followed by a Softmax function to generate dynamic weights for each branch:

where

and

are learnable parameters,

denotes a nonlinear activation function, and

is the adaptive coefficient for the

i-th convolution branch, which satisfies

. The outputs of all branches are then fused in a weighted manner according to these coefficients to obtain cross-scale features:

The fused feature is then passed through a

convolution for channel integration and added to the input feature via a residual connection to produce the final output of the module:

This hierarchical and adaptive design allows HAM to adjust its feature extraction strategy across different scales and semantic levels according to the input content. The dynamic kernel selection mechanism enables the network to focus on local textures in detailed regions while strengthening global responses in structurally or semantically salient areas, thereby achieving efficient fusion of multi-scale features. Residual information flow between layers ensures semantic consistency and stable gradients, while the use of depthwise convolutions effectively reduces the number of parameters and computational cost.

3.4. Fourier Spatial Spectral Modulation (FS2M)

Infrared images primarily reflect the thermal radiation distribution of a scene and are dominated by low-frequency energy. Conventional convolutions operate locally in the spatial domain and thus struggle to fully capture global thermal information, leading to incomplete feature representations. Moreover, standard convolutions lack inherent cross-scale adaptivity, which easily causes attenuation of small target energy and loss of fine details. Due to the discrepancy in spectral response mechanisms between RGB and IR modalities, existing feature extractors also find it difficult to achieve spectral-level alignment and energy balance, which in turn introduces semantic shifts and information distortion during fusion.

We propose the FS2M module, which adaptively enhances infrared features through joint modeling in the frequency, spatial, and spectral domains. This is an improvement on the baseline model C3K2, as shown in

Figure 5, the module mainly consists of cascaded fourier spectral block (FSB) units and CBS blocks. The overall pipeline is illustrated in

Figure 5a. The input feature first passes through a standard CBS block for initial feature extraction and normalization. Then, a channel-wise split operation divides the feature into several parallel subchannels, each of which is fed into multiple stacked FSB units for deep feature transformation. Inside each FSB, a core FDConv [

47] performs feature modulation and enhancement simultaneously in the frequency, spatial, and spectral domains. The outputs of multiple FSBs are concatenated along the channel dimension and passed through a final CBS block for nonlinear combination and reconstruction, yielding an infrared representation with higher semantic consistency and better detail preservation.

FDConv is the key component of FS2M. It breaks the limitation of traditional convolutions with fixed spatial-domain weights by parameterizing the convolution kernels in the frequency domain and enabling adaptive responses to different frequency components. By jointly leveraging frequency-domain modeling, spatial adaptive modulation, and spectral reconstruction, FDConv substantially improves the expressiveness and discriminability of infrared features, and provides FS2M with an efficient and physically interpretable feature extraction mechanism.

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Datasets

We evaluate AsyFusionNet on two benchmarks,

FD [

48] and VEDAI [

49]. The

FD dataset is designed for multimodal and multispectral vehicle detection. It was released in 2017 by the Institute of Computing Technology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and is mainly used to assess detection algorithms in complex environments.

FD contains images captured under diverse environmental and weather conditions, including daytime, nighttime, rain, and haze, covering a wide range of challenging vehicle scenarios. The dataset comprises about 3000 images with a resolution of

, and includes different types of vehicles such as cars, trucks, and buses, together with their bounding boxes and category labels. In addition,

FD provides paired multimodal data, i.e., aligned RGB and IR images, which facilitates cross-modal vehicle detection studies.

The VEDAI dataset is specifically designed for vehicle detection in aerial imagery and was released by the University of Caen, France, in 2015. It contains various categories of vehicles observed from an aerial viewpoint and reflects different illumination conditions, occlusion patterns, and viewing directions. VEDAI provides images in two spectral bands, RGB and IR, in order to enhance the robustness of vehicle detection algorithms in complex environments. The dataset consists of 1246 high-resolution images with resolutions of either or , each annotated with accurate vehicle locations and class labels. Vehicle categories include cars, pickups, trucks, and several other types, covering a broad range of environments and scene configurations.

In our experiments, both FD and VEDAI are split into training, validation, and test sets with a 7:2:1 ratio. Since these are public multimodal benchmarks with well-aligned RGB–IR pairs, we do not perform additional registration beyond the common resize and pad operations applied to both modalities. The data augmentation strategy is kept consistent with the baseline detectors.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the normalized scale distribution of object instances in

FD and VEDAI exhibits markedly different characteristics. For

FD, the scatter points span a wide range, covering targets from extremely small to medium and large scales, with a clear long-tail pattern and multiple clustered groups. This indicates stronger scale diversity and larger intra-class scale variance. In contrast, the scatter distribution of VEDAI is highly concentrated in the small-scale region, and the color distribution is dominated by a few categories, revealing significant class imbalance. These factors pose substantial challenges for robust object detection.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics and Experimental Settings

4.2.1. Evaluation Metrics

In our experiments, the detection performance is evaluated in terms of precision (P), recall (R), average precision (AP) for each class, and mean average precision (mAP) over all classes. All predicted bounding boxes are treated as positive samples. According to their relationship with the ground truth, TP (true positive) denotes the number of correctly detected positive samples, FP (false positive) denotes the number of incorrectly detected positive samples, and FN (false negative) denotes the number of missed positive samples, i.e., ground truth objects that are not detected [

50].

Precision measures the proportion of correct predictions among all positive predictions and reflects the reliability of the detector, whereas recall measures the proportion of correctly detected objects among all ground truth objects and reflects the detector’s ability to find as many targets as possible. These two metrics are closely related to the probabilities of false alarms and missed detections. The area under the precision–recall (P–R) curve for each class is taken as its average precision (AP), and the mean of AP over all classes yields the mean average precision (mAP). The formulas are given as follows:

In this way, mAP can jointly account for the detection performance across multiple categories and avoids the limitations of single-class evaluation metrics. It provides a comprehensive and reliable measure of an object detector’s performance, is naturally suited to multi-class scenarios, reflects the stability of the model, and is straightforward to interpret and compare. Consequently, mAP has become one of the most widely used evaluation metrics in object detection.

We also report several additional indicators. Parameters denote the number of trainable weights in the model. GFLOPs measure the number of floating-point operations required during inference and serve as an important indicator of computational complexity.

4.2.2. Experimental Environment

To ensure fair training and comparison, all ablation studies and training procedures were conducted on the Supercomputing Center of Xijing University. The GPU used is an NVIDIA A800 with 80 GB of VRAM, and the CPU is an Intel 6338N Xeon [

51], both sourced from Intel and NVIDIA Corporation respectively, Santa Clara, CA, USA. The operating system is Red Hat 4.8.5-28. All models are trained under an environment configured with CUDA 12.1, Python 3.11, and PyTorch 2.1. The configuration used for training and testing is summarized in

Table 1.

We train for 300 epochs with a batch size of 16 and use 8 data loading workers. The input image resolution is fixed at

. Stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is adopted as the optimizer, with the learning rate gradually decayed from a maximum of

to a minimum of

. A weight decay of

is applied to mitigate overfitting, and the momentum is set to 0.937. In addition, an early stopping strategy is employed: when the validation loss tends to plateau and the model reaches a quasi-converged state, training is automatically terminated to prevent overfitting. Unless otherwise specified, all compared algorithms are trained and evaluated using their official default hyperparameters. The network structure details of AsyFusionNet are shown in

Table 2.

4.3. Ablation Studies

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed components, we perform ablation studies on both datasets. As a baseline, we construct a dual-branch backbone by extending CSPDarknet53 in YOLOv11 [

52]. In this model, RGB and IR features at corresponding pyramid levels (P3–P5) are fused in a layer-wise manner via a generic concatenation operator, and the resulting features are subsequently fed into the neck and detection head, as illustrated in

Figure 1a.

Table 3 summarizes the ablation results for different RGB/IR backbone depth configurations. With the symmetric P5/P5 setting as baseline, the model achieves

on

FD and

on VEDAI, with 60.0 M and 140.5 M parameters, respectively. Switching to the asymmetric P5/P4 configuration reduces the parameter count to 52.4 M on

FD and 137.7 M on VEDAI, while improving

to

and

. This indicates that increasing IR depth to P5 mainly introduces redundant parameters with limited accuracy gain.

Further truncating the IR branch to P3 leads to a substantial performance drop ( on FD and on VEDAI), suggesting that overly shallow IR features cannot provide sufficient thermal information for effective fusion. Conversely, making the IR branch deeper than the RGB branch (P4/P5) also degrades (to and ), implying that blindly increasing IR depth disrupts semantic alignment between modalities. Overall, the P5/P4 design offers the best trade-off between model size and detection accuracy, supporting the effectiveness of the proposed asymmetric architecture.

Based on the baseline model described above, we conduct ablation studies by incrementally adding each module to evaluate its impact on detection accuracy and computational efficiency. The experimental results are shown in

Table 4. On the

FD dataset, the baseline model achieves

with 60 M parameters. After introducing HAM, the performance increases to

, while the number of parameters drops to 32.4 M, indicating that HAM simultaneously improves accuracy and reduces model complexity. Adding FS2M further boosts

to

. Although the parameter count increases to 57.7 M, FS2M refines feature selection and enhancement, yielding an additional gain. Finally, incorporating LGAF raises

on

FD to

with 59.1 M parameters, providing the best trade-off between detection accuracy and efficiency among all configurations.

On the VEDAI dataset, the overall performance is lower than on FD, reflecting the higher difficulty of this aerial vehicle detection benchmark. The baseline model attains only . After integrating the full set of HAM, FS2M, and LGAF, increases to , corresponding to a gain of 7.7 percentage. The ablation results show that each component contributes positively, with HAM providing the largest improvement by substantially increasing accuracy while reducing the parameter count. FS2M and LGAF offer progressive refinements, further enhancing feature extraction and multi-scale representation learning, and together yield a more powerful and robust multimodal detector.

To further justify the lightweight property of AsyFusionNet, we report both theoretical complexity and practical runtime in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The asymmetric backbone reduces the number of parameters compared with the symmetric baseline (from 60.0 M to 52.4 M on

FD and from 140.5 M to 137.7 M on VEDAI) without increasing the backbone GFLOPs. Moreover, even after introducing the FFT-based FS2M and LGAF modules, the full model still runs at 137.3 FPS on

FD and 92.1 FPS on VEDAI, corresponding to about 7.3 ms and 12.2 ms per image, respectively. Although FS2M slightly decreases the FPS compared to the variant without FS2M, it consistently improves

, and the overall throughput remains far above the common real-time threshold of 30 FPS. In this work, we therefore refer to AsyFusionNet as lightweight in the sense that it maintains a compact parameter count and high frame rate while achieving superior detection accuracy.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

4.4.1. Results on the FD

We conduct a comprehensive quantitative comparison between AsyFusionNet and several representative SOTA detectors, as reported in

Table 5. The compared methods include the classical YOLOv8, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, RT-DETR, Swin Transformer, and multimodal fusion detectors such as CenterNet2, Sparse R-CNN, CDDFusion and MM-DETR. All methods are evaluated under the same experimental setup, using

and

as the primary metrics, and are tested under three configurations: RGB, IR, and multimodal fusion (Multi).

The results show that AsyFusionNet achieves the best performance in the multimodal configuration, with reaching 86.3% and reaching 58.2%, significantly outperforming all competing approaches. For example, the multimodal version of YOLOv8 attains 78.0% and 51.7% . Compared with this baseline, AsyFusionNet brings gains of 8.3% in and 6.5% in , fully demonstrating the superiority of the proposed fusion strategy.

From the single-modality results, AsyFusionNet also delivers strong performance: it achieves 82.0% and 53.4% in the RGB modality, and 78.5% and 51.3% in the IR modality, all clearly exceeding the single-modality results of other methods. It is worth noting that the traditional YOLO series exhibits relatively limited gains after multimodal fusion, whereas our method realizes substantial improvements through an effective cross-modal feature fusion mechanism. In particular, compared with the Swin Transformer, AsyFusionNet improves multimodal by 13.8% and by 17.1%, highlighting the unique advantage of the proposed asymmetric fusion architecture in handling multimodal information.

Moreover, by comparing performance across different modalities, we observe that most methods perform better in the RGB setting than in the IR setting, which is consistent with the lower intrinsic information density of infrared images. In contrast, AsyFusionNet fully exploits the complementary signals of the two modalities and, after multimodal fusion, achieves a substantial performance boost beyond any single modality. This validates the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed cross-modal fusion strategy.

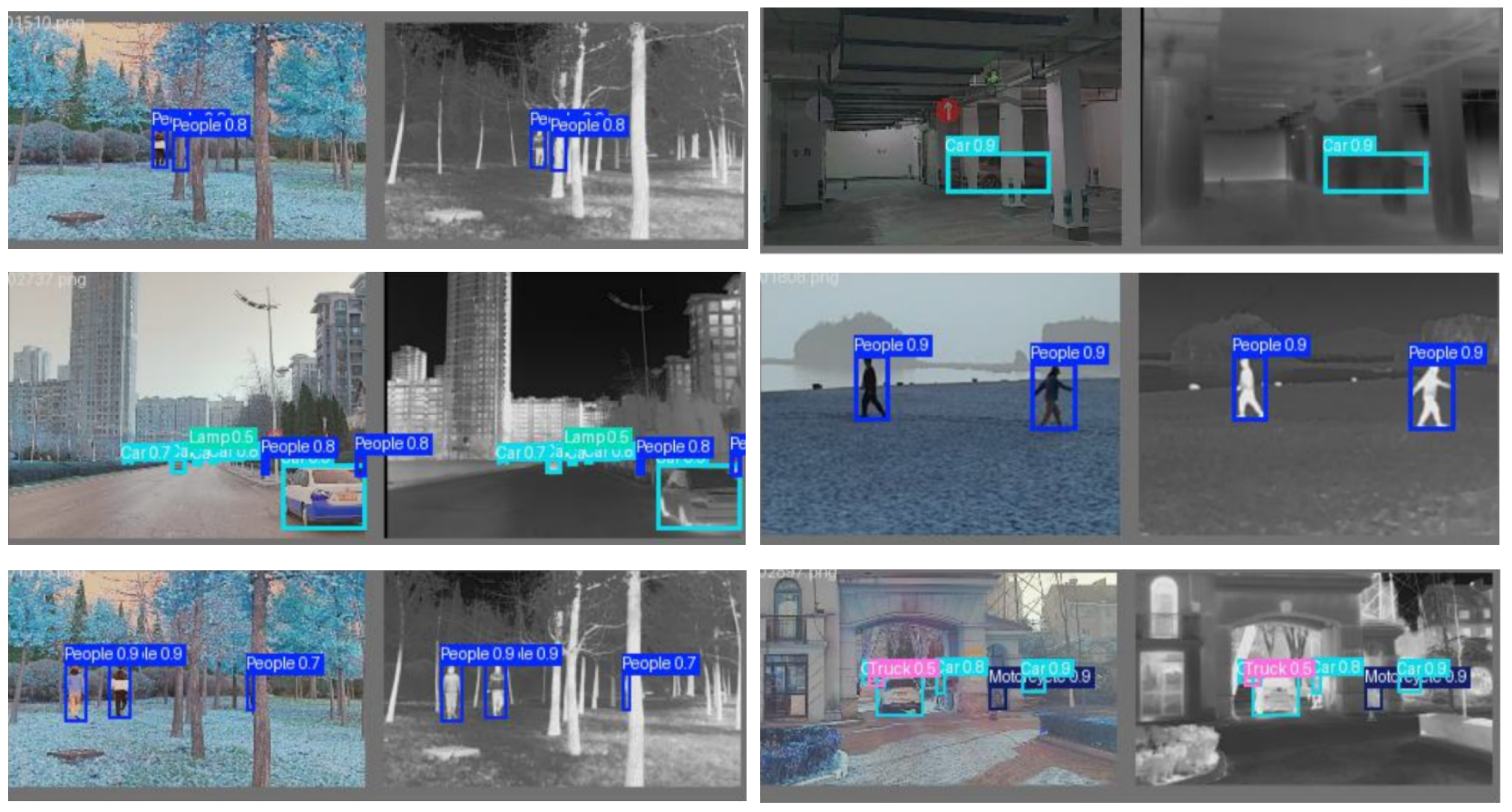

Figure 7 shows detection results of AsyFusionNet on the

FD dataset, where the left column in each group is the RGB image and the right column is the IR image. As can be seen, the proposed method can stably localize different categories of targets in both modalities, and maintains high confidence scores, mostly in the range 0.7–0.9, even under low illumination and strong backlight conditions, effectively suppressing background clutter such as reflections, foliage textures, and building structures. The detector is also able to clearly delineate distant pedestrians and small and long-range targets, demonstrating strong robustness to small and long-range targets.

We further compare the attention distributions of the baseline and the proposed method in multimodal image fusion via visualization-based analysis.

Figure 8 presents two representative pairs of RGB and IR images from the

FD dataset together with their corresponding heatmaps. These scenes cover typical applications such as complex natural environments, human detection, and challenging water surface reflections.

From the heatmaps of the baseline method, it can be observed that conventional fusion strategies suffer from attention dispersion. In particular, the activation regions are overly spread out and lack precise focus on key target areas. In the first natural scene, the baseline’s attention is almost uniformly distributed over the entire image, failing to effectively distinguish foreground targets from the background. In the corresponding infrared scene, although the baseline can roughly highlight the target region, the attention boundaries are blurry and contain a large amount of redundant activation, which severely degrades detection accuracy. In the second lake scene, the baseline is easily disturbed by background factors such as water surface reflections and vegetation textures, causing the attention mechanism to break down and preventing accurate focus on the true targets.

In contrast, AsyFusionNet exhibits clearly superior behavior, with its attention distribution being much more accurate and targeted. Benefiting from the proposed asymmetric fusion architecture, our method can adaptively integrate the complementary cues from RGB and IR modalities to form more robust feature representations. Under the same test scenarios, the heatmaps produced by AsyFusionNet show well-defined target contours and precise boundary localization, while spurious activations in background regions are effectively suppressed. Notably, in the first human detection example, the proposed method accurately outlines the entire human body and remains sensitive to fine details. In the challenging water surface scene, AsyFusionNet, through its cross-modal attention design, successfully overcomes the interference of reflections and complex background textures, achieving precise localization of the true target regions.

4.4.2. Experiment Results of the VEDAI

The experimental results on the VEDAI dataset are reported in

Table 6, where we compare the proposed method with the RGB, IR, and multimodal variants of three generations of general-purpose detectors: YOLOv8, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11. Overall, multimodal fusion consistently outperforms single-modality configurations. Taking YOLOv8/10/11 as examples, their Multi versions improve

over the RGB counterparts by +2.1/+6.2/+1.8%, and over the IR counterparts by +6.3/+6.9/+3.5%, respectively. This confirms the strong complementarity between RGB and IR in terms of appearance textures and thermal radiation cues.

Among all methods, the multimodal version of AsyFusionNet achieves the best overall performance, with 54.1% and 34.7% . These results surpass the strongest YOLOv8–Multi (52.2%/32.2%) by 1.9% and 2.5%, respectively, and yield gains of +7.2/+5.1 and +6.4/+7.2 over YOLOv10–Multi and YOLOv11–Multi. AsyFusionNet shows particularly notable advantages on difficult categories such as boats and tractors, which are easily affected by background clutter or large shape variations. On boats, the improvement over the YOLO multimodal baselines is the most pronounced: +7.4 compared with YOLOv10–Multi and more than +20.0 compared with YOLOv8/11–Multi. This indicates that the proposed cross-modal selection and fusion mechanism can effectively exploit RGB texture details together with the stability of IR thermal imaging, thereby enhancing discrimination for weak-texture or low-contrast targets. For major categories such as car, pickup, and van, AsyFusionNet achieves performance comparable to or better than the best baselines, which in turn leads to consistently higher overall mAP. Although for a few categories (e.g., trucks), some YOLO variants attain slightly higher scores, these improvements tend to be unstable, whereas AsyFusionNet delivers more balanced performance across categories and contributes to a higher overall .

The single-modality comparison further reveals category-dependent modality advantages. For vehicle-like classes such as car and pickup, IR often matches or even surpasses RGB, reflecting the robustness of thermal cues in nighttime or low-contrast conditions. However, for categories such as boats and others, where the temperature difference from the background is small, IR is clearly inferior to RGB, and visible-domain texture and edge information become more crucial. Multimodal fusion can naturally combine the strengths of both modalities and compensate for their respective blind spots, leading to stable improvements in overall performance. In summary, multimodal detection is consistently superior to single-modality detection, and the proposed AsyFusionNet, through adaptive feature selection and fusion, achieves clear gains on both difficult categories and aggregate metrics, demonstrating better cross-modal generalization and robustness.

Detection examples on the VEDAI dataset cover typical aerial scenarios such as residential roads, parking lots, and open highways, which involve a variety of challenges including low-contrast, shadow occlusion, repetitive textures, and distant small targets. As shown in

Figure 9, YOLOv11 produces multiple false alarms caused by high-intensity ground textures, road markings, and roof reflections, marked by red triangles. It also suffers from missed detections and inaccurate localization under partial occlusion and low-contrast backgrounds, for example with bounding boxes that extend beyond the true object extent and category confusions where cars are misclassified as pickup or camping vehicles. In contrast, the proposed method suppresses background clutter more reliably and recovers small targets more faithfully. In both parking lot scenes and long-range road scenes, it can still produce accurate bounding boxes with high confidence scores for vehicles that are small in size or partially covered by shadows, and the category predictions are more consistent. In addition, the bounding boxes generated by our method adhere more tightly to the minimum enclosing rectangles of vehicles, reflecting higher localization accuracy and robustness.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed AsyFusionNet, a multimodal object detection framework whose core innovation lies in an asymmetric dual-branch architecture that explicitly accounts for the different imaging mechanisms of RGB and IR sensors. By extending the RGB branch to the P5 layer while truncating the IR branch at P4, the model reduces computational cost without sacrificing detection accuracy. The LGAF performs joint selective enhancement in the spatial and channel dimensions through parallel local–global attention modeling and a three-branch feature concatenation scheme, thereby improving texture fidelity and semantic consistency. The HAM, tailored to the RGB branch, employs dynamic kernel selection and cross-layer information sharing to better capture both local textures and global structural patterns. The FS2M, designed specifically for infrared features, leverages frequency-domain dynamic convolution to jointly model frequency, spatial, and spectral cues, effectively capturing global thermal radiation patterns and low-frequency energy distributions in infrared images. Extensive experiments on multiple public datasets validate the effectiveness and superiority of AsyFusionNet. Compared with existing mainstream multimodal detection methods, the proposed framework achieves a more favorable accuracy–speed trade-off and exhibits stronger robustness, particularly in complex backgrounds and small-object detection scenarios. Ablation studies further confirm the contribution of each component, showing that the proposed modules work synergistically to boost overall detection performance.

Nonetheless, several limitations remain. First, although the asymmetric architecture improves computational efficiency, truncating the IR branch may lead to the loss of high-level semantic information in certain scenarios, potentially affecting the recognition of more complex targets. Second, the frequency-domain transforms in FS2M still incur non-negligible computational overhead for large input resolutions, which constrains its applicability to ultra-high-resolution imagery. In addition, the current framework is mainly optimized for RGB and IR fusion, and its adaptability to other modality combinations, such as RGB and depth, RGB and LiDAR, requires further investigation. Compared with RGB and IR, RGB–Depth and RGB–LiDAR fusion introduces additional challenges such as heterogeneous spatial resolution, sparse and irregular sampling (for LiDAR), missing depth measurements, and stricter requirements on geometric alignment and calibration, which may make simple extensions of the current design suboptimal. Improving robustness under extreme weather and severe occlusion remains an important direction for future work.

Future work will focus on exploring adaptive asymmetric architectures that dynamically adjust the depth and complexity of each branch according to application scenarios, so as to better balance accuracy and efficiency; developing more efficient frequency-domain processing schemes to reduce the computational burden of FS2M and enhance its scalability to high-resolution inputs; extending the framework to support a broader range of modality combinations and cross-domain applications; incorporating adversarial training or domain adaptation techniques to improve robustness under adverse conditions; and integrating knowledge distillation and model compression to further optimize deployment efficiency on edge devices with real-time requirements. In addition, we plan to conduct a more comprehensive analysis, including a comparison between symmetric and asymmetric designs in challenging scenarios such as dense fog, severe occlusion, and small-object detection. These directions will help push multimodal object detection toward more practical and intelligent applications.