1. Introduction

Malware refers to program code designed to damage or exploit computer systems. It can be categorized into viruses, worms, Trojans, spyware, adware, crawlers, ransomware, and other types according to their propagation methods, payloads, and functionalities [

1]. With the rapid development of information technology, the destructive power and impact of malware continue to grow. According to statistics from Kaspersky, its detection system identified an average of 467,000 malicious files per day in 2024—an increase of 14% compared to the previous year. Windows systems were the primary targets, accounting for 93% of daily detected malware [

2].

Attackers often employ obfuscation techniques to disguise malware and evade detection, gradually rendering static feature-based malware detection methods ineffective [

3]. In contrast, dynamic detection methods analyze malware based on runtime behaviors and are less affected by evasion techniques [

4]. Since all malware ultimately aims to perform malicious operations regardless of disguise, behavior-based dynamic detection methods have proven more effective [

5].

Application Programming Interface (API) call sequences capture the behavioral logic of programs interacting with the operating system during execution [

6]. The order and combination patterns of API calls can effectively distinguish different software categories [

7]. In recent years, with advances in artificial intelligence, researchers have applied deep learning techniques to analyze malware API call sequences. These approaches include Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

8], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

9], and hybrid models combining Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

10] and Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) [

11] networks. By learning local patterns and temporal dependencies from API sequences, these models have achieved promising results in malware detection.

However, existing detection methods still face several challenges. CNNs have a limited receptive field, making it difficult to capture long-range temporal dependencies. Although RNNs and their variants are suitable for modeling temporal relationships, they struggle to extract fine-grained local features. Hybrid models can combine local and temporal information but still lack the ability to model global dependencies. Moreover, most models rely on existing datasets for training, leading to two key issues: (1) severe class imbalance, where models perform well only on majority classes, and (2) limited generalization, as training data typically consist of known malware samples, reducing detection effectiveness against mutated or unknown variants.

To address the problems of data imbalance and sample scarcity, this study proposes a Transformer-based Conditional Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (CWGAN-GP) to generate high-quality minority-class samples, thereby achieving semantic data augmentation, balancing class distribution, and enhancing model generalization. In addition, to overcome the limitations of existing feature extraction methods, we design a hybrid malware detection architecture that integrates a Text Convolutional Neural Network (TextCNN) with a Transformer Encoder. This model captures multi-scale local patterns as well as global dependencies information, enabling accurate identification of complex malicious behaviors.

In summary, the main contributions of this study are as follows:

1. To address the issues of data imbalance and sample scarcity, we propose a Transformer-based CWGAN-GP for semantic data augmentation. This approach generates high-quality minority-class samples, effectively balancing the dataset and improving the model’s generalization ability. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to apply CWGAN-GP to semantically constrained malware API sequence generation.

2. To overcome the limitations of existing feature extraction methods, we design a hybrid malware detection model that integrates a TextCNN with a Transformer Encoder. This architecture captures both multi-scale local patterns and global dependencies from API call sequences, enabling more accurate and comprehensive behavioral representation. The dual-branch feature extractor demonstrates complementary strengths and alleviates the limitations of using either CNN or Transformer alone.

3. We construct an end-to-end malware detection framework that combines semantic data augmentation with hybrid feature extraction to achieve robust and precise classification of malicious behaviors. Experimental results on two public datasets demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms traditional machine learning and mainstream deep learning models in terms of accuracy, precision, and F1-score, particularly improving the detection of minority-class malware samples. In addition, robustness evaluation under obfuscation-based and adversarial perturbations further confirms the model’s stability in realistic evasion scenarios.

3. Proposed Method

This section provides a detailed description of the framework of the proposed detection method. Studies have shown that each type of malware exhibits distinctive API call patterns or sequences [

23]. Based on this observation, the proposed approach takes API call sequences as the primary analysis target to mine behavioral patterns and temporal features within the sequences for identifying different types of malware.

From the perspective of structural design, our framework incorporates a form of feature-level symmetry by jointly modeling global semantic dependencies and local discriminative patterns. This symmetry reflects the assumption that robust malware characterization requires a balanced representation between long-range behavioral structures and short-span execution signatures. By explicitly pairing a global Transformer branch with a local TextCNN branch, the architecture enforces a symmetrical dual-view analysis of API sequences, ensuring that neither global nor local information dominates the representation. This design choice provides clearer theoretical grounding for the symmetry connection mentioned in the introduction.

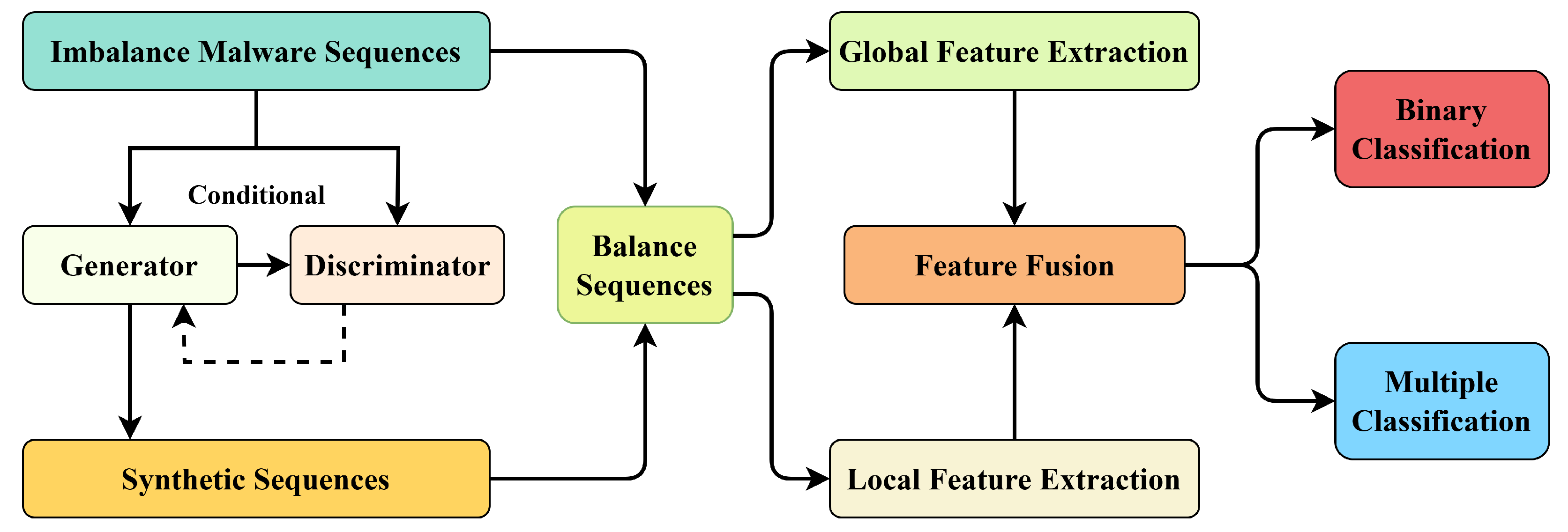

Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed malware detection framework. Imbalanced malware API sequences are first input into a conditional generative adversarial network architecture consisting of a generator and a discriminator. By learning class-conditional sequence distributions, the generator synthesizes new samples that are combined with the original dataset to construct a balanced training set. The balanced sequences are then processed by a dual-branch feature extraction module, where one branch captures global semantic dependencies and the other focuses on local discriminative patterns. The two types of representations are subsequently integrated through a feature fusion module to obtain a unified semantic embedding, which is finally fed into the classification layer for both binary and multi-class malware detection.

Building upon this high-level workflow,

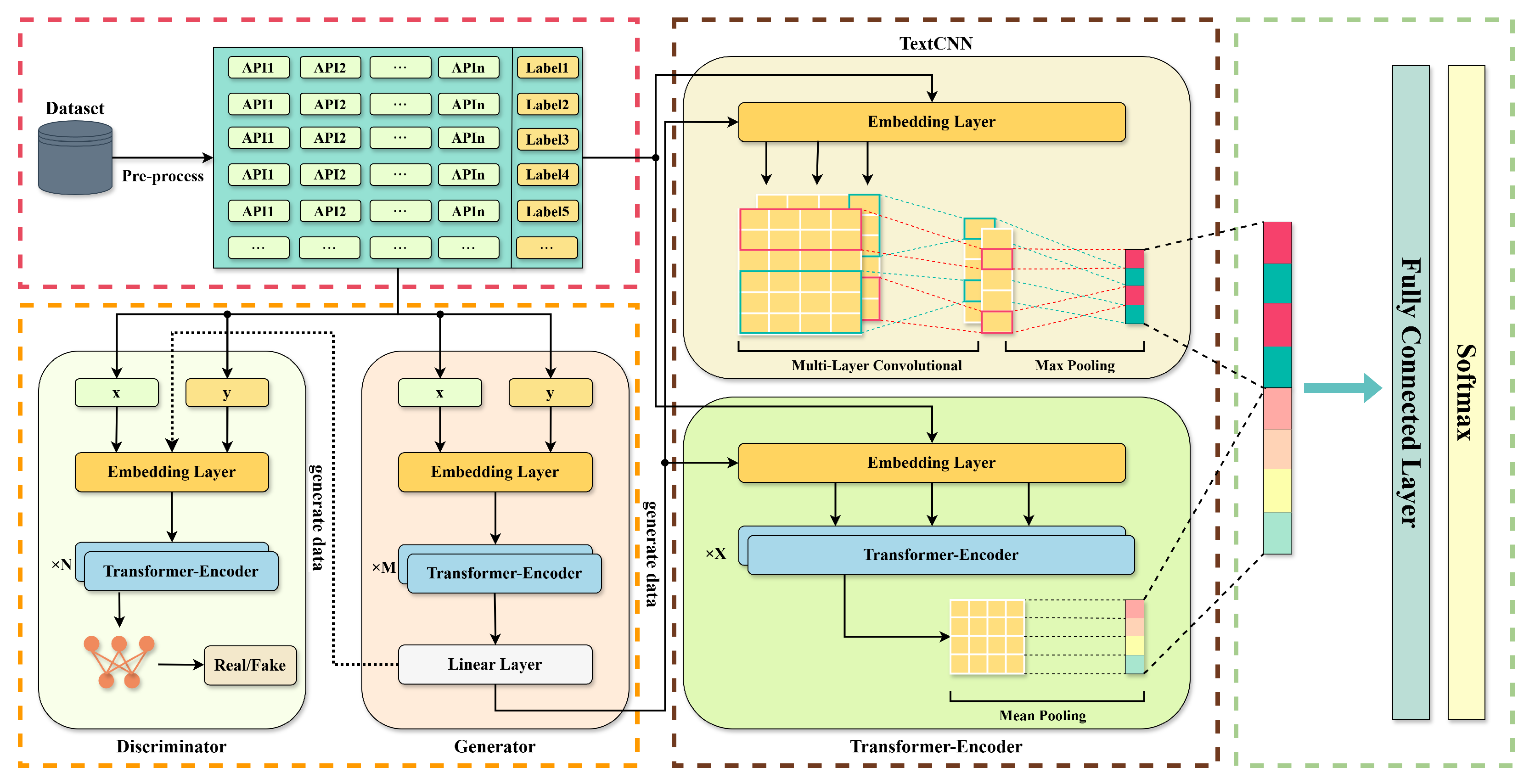

Figure 2 illustrates the full architectural design of the proposed model, consisting of three primary components: the data preprocessing module, the data augmentation module, and the classification and detection module. The following subsections describe each module in detail.

3.1. Dataset

The experimental data used in this study are derived from the Alibaba Cloud security malware detection dataset [

24]. This dataset contains a total of 600 million records, representing desensitized API calls extracted from Windows executable files executed in a sandbox environment. Since the official test set of the dataset does not include class labels, this study uses only the training set as the overall data source and discards the test set.

As shown in

Table 1, the dataset comprises eight categories: benign software, ransomware, cryptocurrency mining programs, DDoS Trojans, worms, infectors, backdoors, and Trojan programs, with a total of 13,877 binary samples. The dataset contains over 89 million API call records, with each file averaging 6466 API calls, and a maximum of 888,204 calls in a single file.

As illustrated in

Table 2, each record in the dataset consists of five fields: file ID (file_id), category label (label), API name, thread ID (tid), and call index (index) within the thread. Within the same thread, API calls are executed in ascending order of the index, while there is no strict ordering relationship between different threads.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.2.1. Suffix Delete

In the Windows operating system, multiple API names may correspond to the same functionality. For example, RegOpenKey and RegOpenKeyEx are both used to open a registry key, with the latter being an extended version of the former. In addition, some APIs append the suffix A (indicating ASCII) or W (indicating Unicode) depending on the input format. These naming differences originate from Windows’ design evolution to support different system architectures (e.g., from 16-bit to 64-bit) [

25]. However, in malware detection, such naming variations may cause the model to treat semantically equivalent API calls as distinct features, thereby reducing its generalization capability. In our experiments, we used regular expressions to standardize API calls by removing related suffixes such as A, W, Ex, ExW, and ExA.

3.2.2. Deduplication and Concatenation

In the raw collected data, a large number of repeated API calls exist due to program logic or obfuscation techniques. These redundant calls not only increase the sequence length but also introduce noise that can interfere with subsequent model training. Therefore, it is necessary to perform deduplication on the API calls in the dataset. For API calls within the same thread, the sequence is scanned in its original order, and only the first occurrence of each API is retained, while all subsequent duplicates are removed. This process reduces sequence length and eliminates redundant information.

After deduplication, API calls within each thread are concatenated into a single string separated by spaces, forming a new data format with each thread as the basic unit.

3.2.3. Truncation and Padding

During dynamic execution, each sample may generate API calls from multiple threads. For API calls within the same thread, the original calling order is strictly preserved. For API call sequences composed of multiple threads, the sequences are concatenated directly, and a delimiter is inserted between adjacent threads to maintain boundary information. When the concatenated sequence length exceeds the predefined maximum length, it is truncated accordingly. Conversely, if the total number of API calls across all threads is shorter than the maximum length, the sequence is padded with 0 at the end to ensure a consistent input length across all samples.

3.2.4. Building the Vocabulary

After completing the above processing steps, the API call text sequences must be converted into numerical sequences that can be processed by the model. Based on all APIs appearing in the dataset, a vocabulary is constructed in which each API is assigned a unique integer index, enabling the mapping of string sequences to corresponding numerical sequences. The overall algorithm of the data preprocessing module is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: API Sequence Preprocessing |

![Symmetry 17 02153 i001 Symmetry 17 02153 i001]() |

3.3. Data Augmentation

To alleviate the issue of class imbalance commonly observed in malware datasets, we propose a data augmentation framework based on a Transformer-driven Conditional Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (CWGAN-GP) to generate high-quality synthetic samples.

Existing augmentation approaches exhibit notable limitations when applied to malware sequence generation. Oversampling techniques such as SMOTE and its variants rely on linear interpolation in the feature space, which disrupts the semantic and contextual dependencies inherent in API-call sequences, resulting in synthetic data that fail to reflect realistic malicious behaviors. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), although capable of generating samples through latent-space modeling, tend to produce over-smoothed and averaged representations due to the KL-divergence constraint, weakening important behavioral patterns and making them less suitable for modeling multi-modal or minority-class distributions. Prior studies have also shown that VAE-generated samples yield only marginal performance gains, whereas GAN-based approaches provide more substantial improvement [

19]. Traditional GANs, however, often suffer from instability and mode collapse, limiting the semantic fidelity and diversity of augmented samples. In contrast, the proposed CWGAN-GP framework provides a more stable and semantically faithful solution for malware sequence generation. By incorporating the Wasserstein distance, the model achieves a more precise estimation of distributional divergence, enabling the generator to capture fine-grained, multi-modal malicious behavior patterns without collapsing into a limited set of modes. The gradient penalty further enforces the Lipschitz constraint and mitigates issues such as gradient explosion or vanishing, thereby enhancing training stability and improving the reliability of the synthesized sequences. More importantly, semantic fidelity is strengthened through conditional generation: class labels are embedded into both the generator and discriminator, ensuring that the model preserves class-specific behavioral semantics and produces samples that remain consistent with the underlying malicious activity patterns.

Traditional GAN architectures built on CNNs or RNNs are generally effective for images or short sequences but struggle to capture long-range dependencies within API call sequences. Inspired by the effectiveness of TTS-GAN in sequence generation tasks [

26], we integrate a standard Transformer encoder into the CWGAN-GP framework. The self-attention mechanism allows the model to effectively capture global temporal dependencies and deeper semantic relationships across API sequences, enabling the generation of synthetically enriched, semantically coherent, and class-distinguishable malware samples. This approach not only improves the diversity of generated data but also significantly enhances detection performance, especially for minority classes.

3.3.1. Transformer

The Transformer model was proposed by researchers at Google in 2017 [

27] for sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) tasks, and it has since been widely applied to various sequence modeling problems. Its core component, the self-attention mechanism, has enabled it to achieve outstanding performance in fields such as natural language processing and time-series analysis.

Compared with RNN, the Transformer eliminates the recursive structure, allowing highly efficient parallel computation. In contrast to CNN, the computational complexity of dependency modeling between any two positions in a Transformer is independent of their distance, thereby enabling global dependency modeling. Moreover, the multi-head self-attention mechanism allows the Transformer to focus on different positions of the input sequence simultaneously, with each attention head learning distinct features in different subspaces. This makes the Transformer particularly suitable for handling long and complex sequences such as malware API call sequences.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the Transformer model consists of two main components: an encoder and a decoder, which work together to extract features from the input sequence and generate the target sequence. The encoder is responsible for extracting high-dimensional feature representations and capturing global dependencies among sequence elements. Its core operation is the multi-head self-attention mechanism, which adaptively adjusts the weight distribution among different positions within the sequence, thereby enabling dynamic global feature modeling. The core computation is expressed as follows:

where

Q,

K, and

V denote the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, obtained through learnable linear transformations of the input data, and

represents the dimension of the key vectors. The encoder also contains a Feed-Forward Network (FFN), which applies nonlinear transformations to each position’s representation to enhance the model’s expressive power.

The decoder generates the target sequence step by step based on the encoder’s output and the partially generated sequence. Each decoder layer consists of three submodules: a masked self-attention mechanism, an encoder–decoder attention mechanism, and a FFN. This design allows the decoder to consider both previously generated content and the global dependencies information from the input sequence when producing each output position.

Since the Transformer itself lacks an inherent mechanism for positional information, Positional Encoding (PE) is introduced during word embedding to preserve the order of sequence elements. The computation is defined as follows:

where

denotes the position index,

i represents the feature dimension index, and

is the dimensionality of the feature vector.

3.3.2. CWGAN-GP

CWGAN-GP is a variant of the GAN [

28], which innovatively integrates and improves upon the strengths of the Conditional GAN (CGAN) and the Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP).

The first improvement originates from the CGAN, where conditional information is incorporated into the adversarial process. This allows the generator to produce samples corresponding to specific class labels, while the discriminator evaluates whether an input sample is both realistic and consistent with the given label. Consequently, the generator is guided to synthesize data that better aligns with label semantics.

The second improvement comes from the WGAN-GP, which replaces the traditional Jensen–Shannon (JS) divergence with the Wasserstein distance as the optimization objective, and introduces a gradient penalty term in the discriminator’s loss to enforce the 1-Lipschitz constraint. This modification enhances training stability and alleviates the mode collapse problem. The Wasserstein distance is defined as follows:

where

denotes the real data distribution,

represents the generated data distribution, and

f is a discriminator function that satisfies the 1-Lipschitz condition.

The gradient penalty term is computed as follows:

where

is the gradient penalty coefficient, and

denotes interpolated samples obtained by linear interpolation between real and generated samples from

and

, respectively. The interpolation process is defined as follows:

By combining the two improvements described above, the final objective function of CWGAN-GP can be formulated as follows:

3.3.3. Data Augmentation Framework and Training Process Based on CWGAN-GP

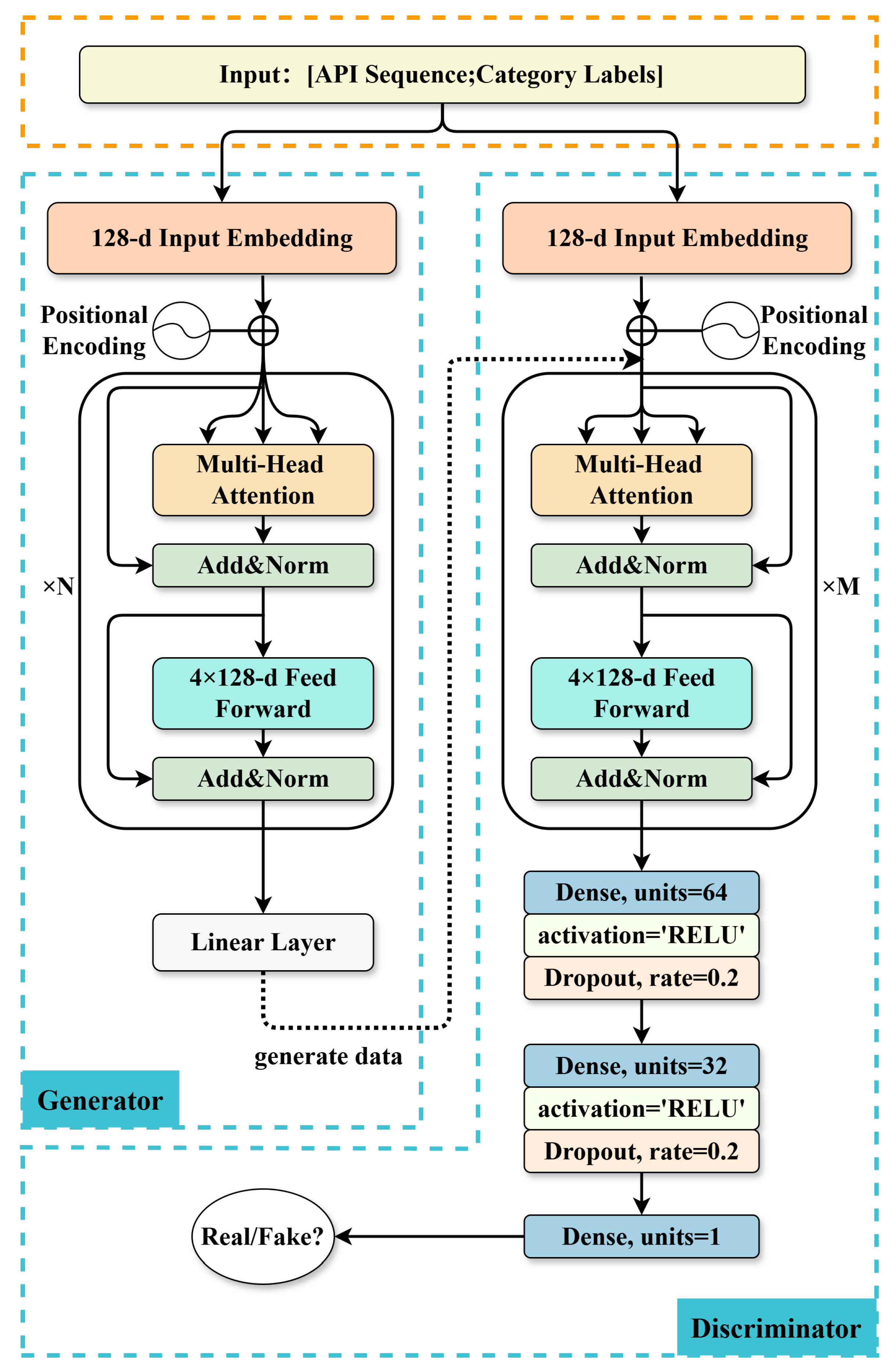

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the overall framework of the data augmentation model consists of two main components: a generator and a discriminator.

The input layer maps API sequences and their class labels into 128-dimensional embeddings and adds positional encodings to incorporate sequential order. The generator, composed of N layers of Multi-Head Attention with Add&Norm and 4 × 128 feed-forward networks, captures global dependencies within sequences and produces semantically consistent synthetic API samples through a final linear layer. The discriminator, built with M layers of the same Transformer architecture followed by 64/32-dimensional fully connected layers with ReLU activation and Dropout, evaluates the authenticity of the input sequences. Through adversarial training, the generator learns to create high-quality API sequences that closely resemble real samples, providing enhanced and balanced data for downstream classification tasks.

Specifically, during the training phase, we first sample a noise vector

from a standard normal distribution and combine it with the class label

y as the input to the generator. In the generator, the input label

y is mapped into a dense vector representation

through an embedding layer, which is then repeated and expanded to match the sequence length. This expanded label embedding is concatenated with the input noise vector to form a conditional representation

. Subsequently,

is projected into a feature space of dimension

, compatible with the Transformer-Encoder, and a learnable positional encoding is added. The computation can be formalized as follows:

where

denotes a linear transformation matrix, and

represents the learnable positional encoding matrix.

The encoded representation

is then passed into the Transformer-Encoder to learn contextual semantic dependencies, yielding a hidden representation

. A subsequent linear transformation maps

into the embedding space, producing the generator’s final output

, as expressed by:

Since the generator produces synthetic samples in embedding space, the discriminator receives either real samples or generated embeddings as input. In the discriminator, the input class label y is embedded into a dense vector . Depending on the input type, different processing paths are followed. For real samples , the API sequence is embedded into a dense representation and concatenated with to form . For generated embeddings , the concatenation with directly yields . These conditional representations are then fed into the discriminator’s Transformer-Encoder, resulting in contextual representations .

To extract global features, we perform mean pooling along the sequence dimension of

, computed as follows:

Finally, this pooled feature vector is fed into a fully connected network for real/fake discrimination, which can be expressed as follows:

where

denotes the Rectified Linear Unit activation function, and

is the sigmoid activation used for final discrimination.

3.4. Classification Detection

To evaluate the effectiveness of data augmentation and the capability of malware discrimination, we designed a classification and detection module. This module serves two primary purposes: (1) to verify whether the augmented samples exhibit a distribution consistent with real data, thereby assessing the quality and semantic validity of the generated samples; and (2) to act as the feature extractor and classifier within the malware detection framework.

Analysis of API Call Patterns in Malware Families

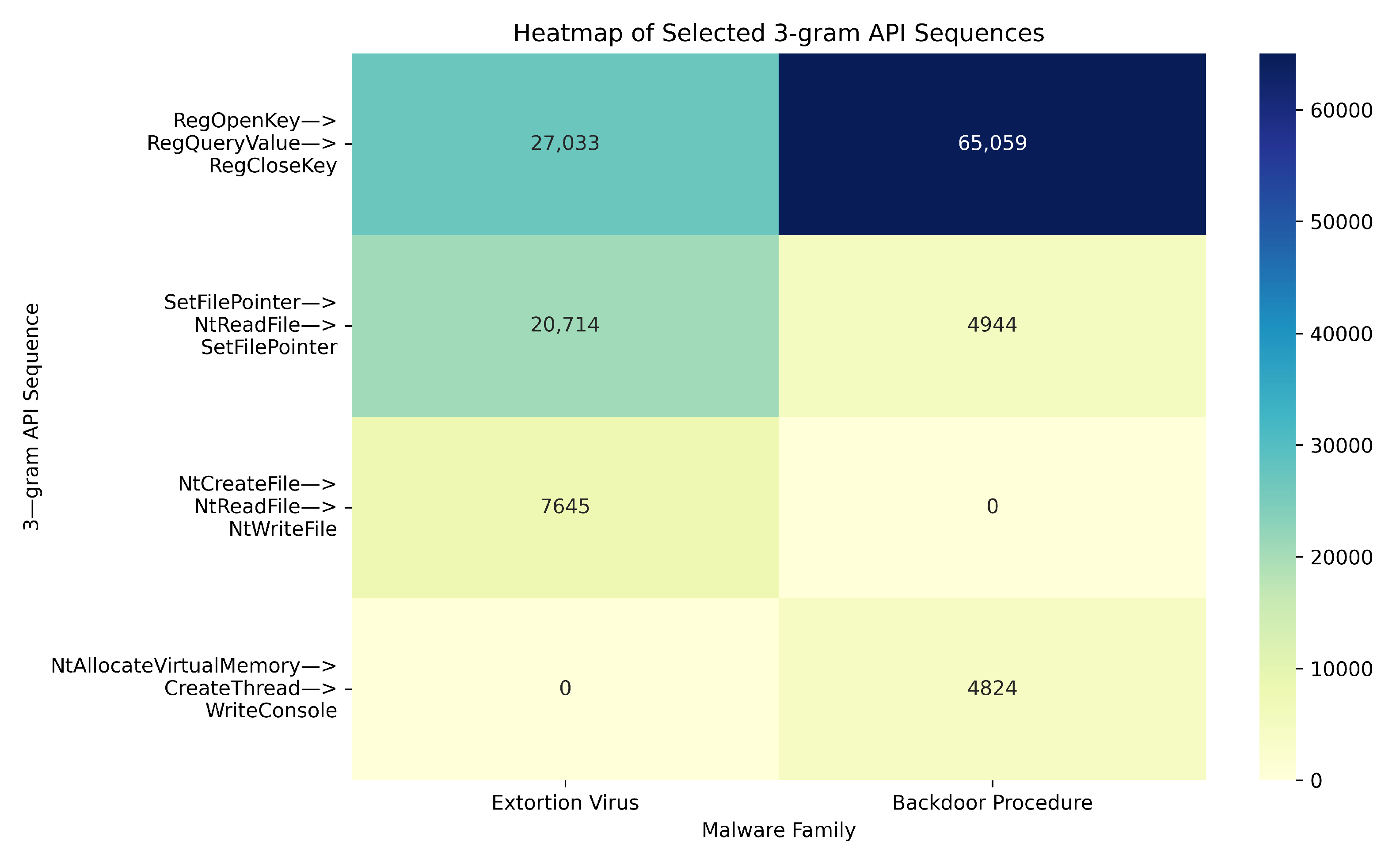

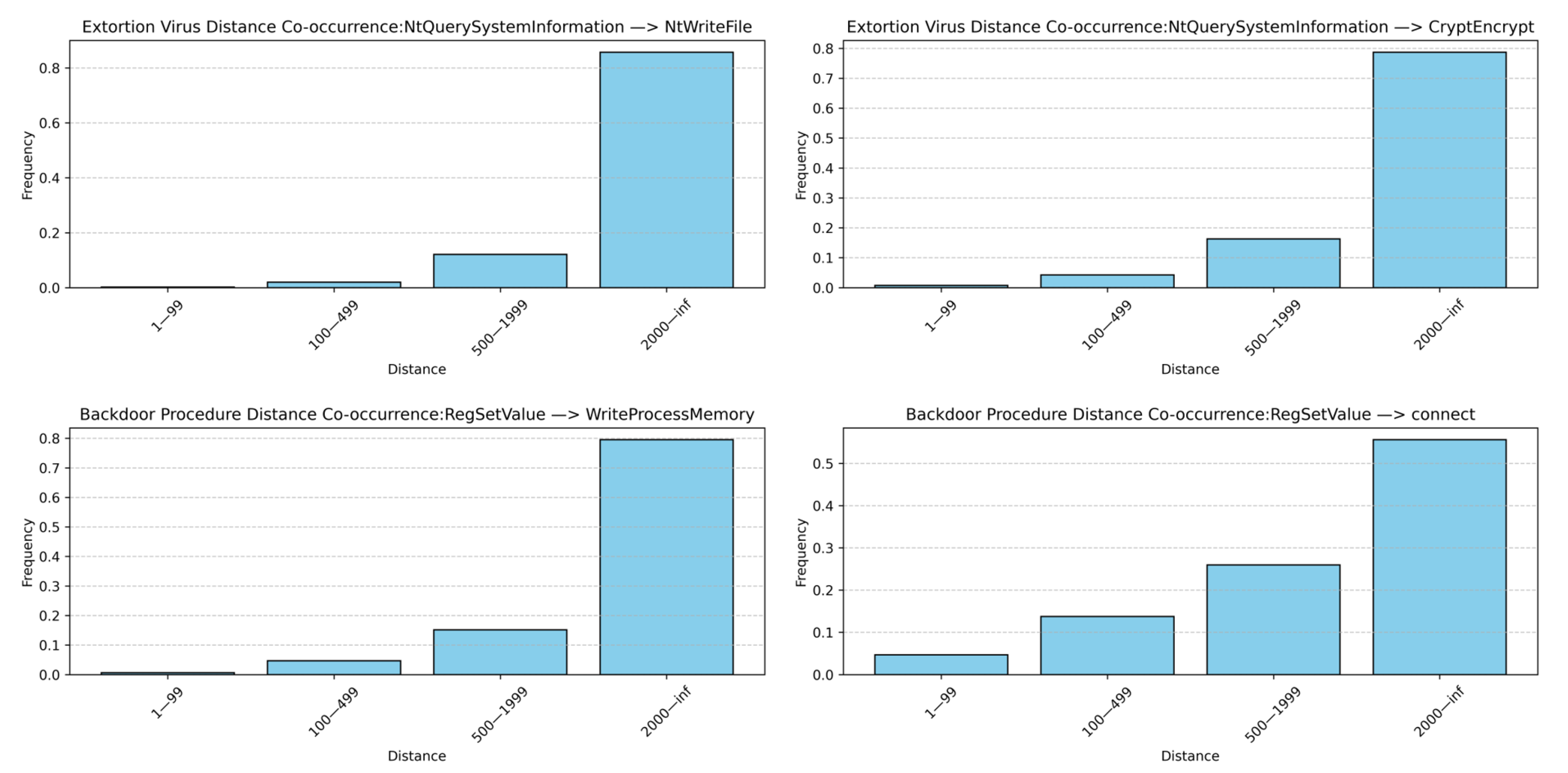

Different types of malware exhibit distinct local API call patterns during execution. These patterns provide valuable discriminative cues for subsequent feature extraction and classification decisions. Taking ransomware and backdoor families from the unfiltered Alibaba Cloud security dataset as examples, four representative 3-g API call patterns were selected and compared using heatmaps. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the two malware families show significant differences in both attack behavior and system interaction modes:

Ransomware tends to perform a large number of file operations. Before encrypting user files, it frequently calls API sequences such as “NtCreateFile NtReadFile NtWriteFile”, forming a highly concentrated file operation pattern. Moreover, the frequent appearance of “SetFilePointer” and related APIs further strengthens its intensive interaction with the local file system.

Backdoor malware, on the other hand, frequently invokes APIs such as “RegOpenKey RegQueryValue RegCloseKey” to tamper with system startup and service registry entries, maintaining persistent presence within the system. During execution, backdoors also make heavy use of “NtAllocateVirtualMemory CreateThread WriteConsole” to implement remote code injection and malicious thread creation, enabling covert control. These composite patterns clearly differ from those of ransomware: while ransomware exhibits high activity in file operations, backdoors are more active in memory manipulation and system configuration modification.

In addition to local pattern differences, malware families also display long-range dependency relationships within their API call sequences. Using the same Alibaba Cloud security dataset, two key API pairs were selected from ransomware and backdoor samples to analyze co-occurrence relationships at varying distances. As shown in

Figure 6, ransomware typically calls the system information query function “NtQuerySystemInformation” to perform environment checks, followed by the file encryption function “CryptEncrypt”—often separated by more than 500 API calls. Similarly, backdoor malware calls “RegSetValue” to complete persistence configuration operations but does not immediately initiate malicious activities. Instead, after a period of normal or deceptive behavior, it calls “connect” or “WriteProcessMemory” for communication or memory injection.

Such long-distance API co-occurrences, though not adjacent, are semantically correlated and reveal the latent long-range dependencies in malware execution behaviors.

In summary, malware API call sequences contain both local sequential patterns and long-range dependencies. Local patterns represent the atomic operational units of malicious behaviors, exhibiting strong family consistency and discriminability. Long-range dependencies, on the other hand, reflect the logical relationships between different attack stages, revealing the complete attack chains and strategic variations among malware families. Therefore, an effective malware detection model must possess both local feature extraction capability and global dependency modeling ability to comprehensively characterize and accurately identify complex malicious behaviors.

3.5. Malware Detection Model Based on TextCNN and Transformer-Encoder

To fully capture features of malware API call sequences at multiple scales, we employ a hybrid modeling approach that combines the TextCNN and the Transformer-Encoder. The TextCNN utilizes convolution kernels of varying sizes as sliding windows to effectively capture local combination patterns between adjacent API calls. In contrast, the Transformer leverages a self-attention mechanism to perform global modeling of API call sequences, capturing long-range dependencies between any pair of API calls and addressing the limitations of convolutional and recurrent networks in transmitting information over long sequences.

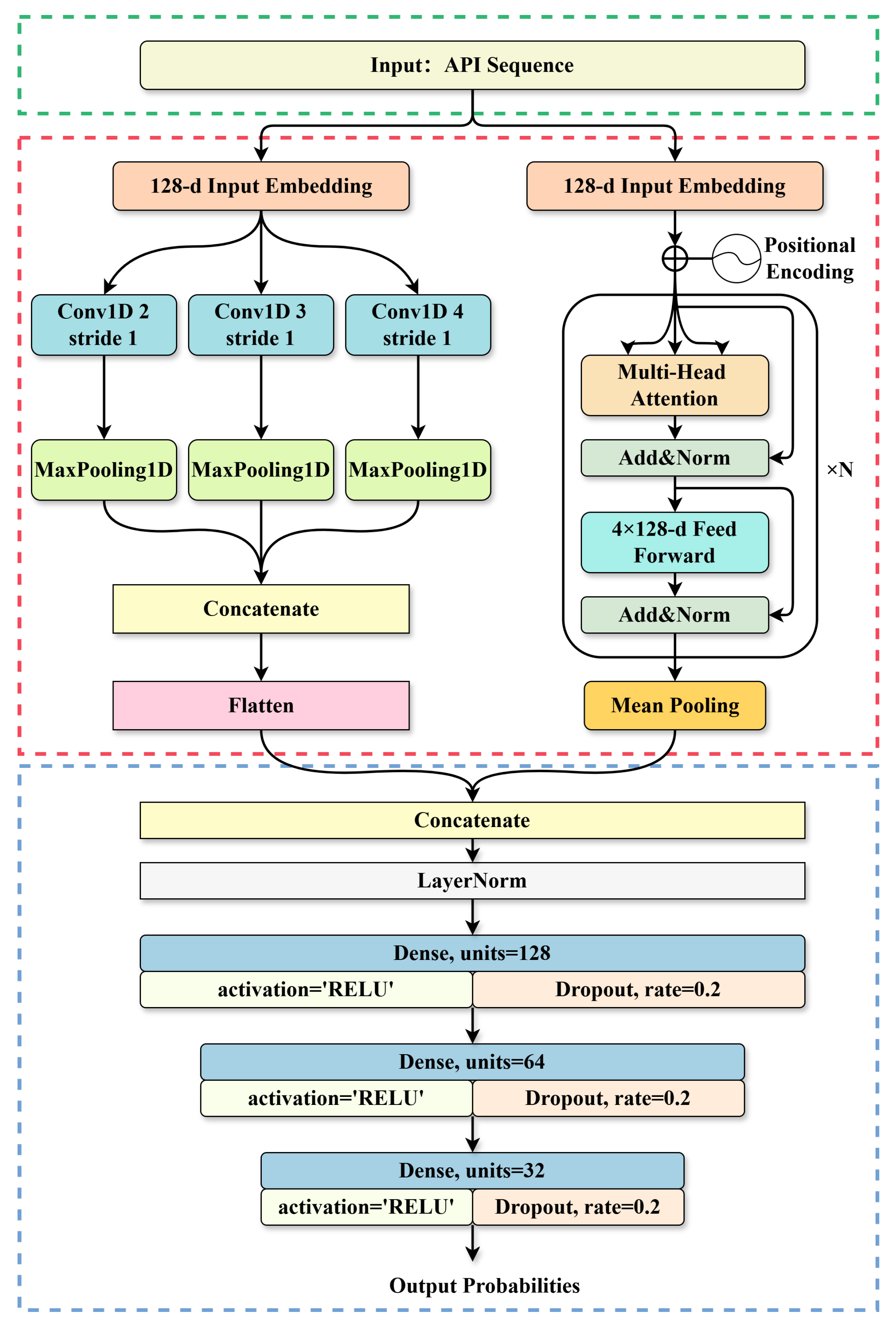

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the overall framework consists of three components: TextCNN, Transformer-Encoder and Classifier.

The left branch (TextCNN) embeds the input and uses multi-kernel Conv1D layers with MaxPooling to capture local patterns, producing a local feature vector. The right branch (Transformer-Encoder) embeds the sequence with positional encodings and passes it through Transformer layers to model long-range dependencies, yielding a global feature vector. The two feature vectors are concatenated and processed by fully connected layers with ReLU activation, Dropout, and layer normalization to produce the final prediction. This dual-branch design enables the model to jointly leverage fine-grained and contextual information for accurate malware classification.

In the TextCNN module, the input sequence is first transformed into an embedding representation

through an embedding layer, where

L denotes the sequence length and

d the embedding dimension. Convolution operations are then performed using multiple convolution kernels of different sizes. For a convolution kernel with window size

h, the convolution operation can be formalized as follows:

where

represents the convolution kernel weights,

is the concatenation of embedding vectors from position

i to

,

is the bias term, and

denotes a nonlinear activation function.

After convolution, a max-pooling operation is applied over each feature map to obtain the most representative local feature, which is formulated as follows:

Given

n different convolution kernel sizes, the final local feature representation from the TextCNN is obtained by concatenating all pooled features, which is calculated as follows:

In the Transformer-Encoder module, the input sequence is first passed through a word embedding layer with absolute positional encoding, preserving sequential structure while mapping tokens into dense vectors of fixed dimension. The embedded representation is then processed through multiple encoder layers, each consisting of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward sublayers, with residual connections and layer normalization. The output is a contextualized sequence representation containing global dependency information.

We then apply average pooling across the sequence dimension to aggregate global dependencies information into a fixed-length global feature vector, which is calculated as follows:

The local feature vector

and the global feature vector

are concatenated to form the joint feature representation, which is calculated as follows:

To mitigate the distributional differences between the two feature branches, the fused feature vector is normalized via layer normalization before being fed into the classifier.

The classifier is a multilayer perceptron (MLP) consisting of three hidden layers, each followed by a ReLU activation and a dropout operation to enhance nonlinearity and reduce overfitting. The model is trained under the supervision of the cross-entropy loss function, which minimizes the discrepancy between the predicted and true labels, which is formulated as follows:

where

and

denote the true and predicted class probabilities, respectively.

To prevent the deep hybrid model from overfitting to the samples generated by the CWGAN-GP, several regularization strategies were incorporated into the training process.

Although the total number of generated samples is substantially larger than the number of real samples, each training batch was constructed using an equal proportion of real and synthetic sequences. Since real samples are limited, they were iteratively reused to maintain this 1:1 ratio, ensuring that the model does not become biased toward synthetic patterns despite the large volume of generated data. In addition, weight decay and dropout were applied to both the Transformer and convolutional modules to reduce feature co-adaptation and enhance generalization. Early stopping based on validation loss was further employed to prevent the model from memorizing synthetic sequences during training. Moreover, the CWGAN-GP architecture inherently alleviates mode collapse and overfitting through the gradient-penalty mechanism, which enforces smoother distribution learning and contributes to the stability of the generated data.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental environment used in this study is configured as follows: the operating system is Windows 10 Professional (64-bit), equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12400 @ 2.40 GHz processor, 16 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU, with a 1 TB SSD for storage. The implementation was carried out using the Python 3.9 programming language, based on the PyTorch 2.3 framework, with CUDA version 12.1. Auxiliary development and visualization libraries include NumPy 1.26.4, Pandas 1.2.4, Scikit-learn 1.6.1, Matplotlib 3.5.1 and Seaborn 0.13.2, all of which are open-source tools available for free via the Python Package Index (PyPI).

To ensure consistent input format and efficient processing of sequential behaviors, all API call sequences were standardized to a fixed length of 256. The hyperparameters used in both the data augmentation and classification stages are summarized in

Table 3.

For the CWGAN-GP-based data augmentation module, the Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of and a batch size of 32. The gradient penalty coefficient was set to 10, which we empirically found to be effective in stabilizing the training process while preventing mode collapse. The generator and discriminator were trained for 12 epochs, a duration we determined through trial and error, which provided stable convergence and prevented overfitting or instability. The learning rate and other hyperparameters were chosen after a series of preliminary experiments, where different values were tested to assess their impact on both the convergence rate and the quality of generated samples.

For the Mal-CGP-TTN feature extraction and classification module, we also used the Adam optimizer with the same learning rate of and a weight decay of . The model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32. Based on empirical observations, we found that extending training beyond 50 epochs led to increased fluctuations in both loss and accuracy, signaling overfitting. Thus, 50 epochs offered a good balance between convergence stability and generalization. The choice of 50 epochs was also determined after experimenting with various epoch values, considering both the convergence rate and the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data.

4.2. Train and Test Datasets

In the binary and multi-class classification experiments, the Alibaba Cloud security malware detection dataset was randomly divided into training and testing sets in a 4:1 ratio. A stratified sampling strategy was adopted during the splitting process to ensure consistent class distribution between the training and testing sets. Subsequently, data augmentation was performed on the training set using the CWGAN-GP model, expanding the minority classes to match the size of the majority class, while keeping the test set unchanged. The augmented training set contained a total of 31,856 samples. The detailed data partitioning information is shown in

Table 4.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the model in the malware detection task, this study adopts Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score as the primary evaluation metrics. Among them, Precision represents the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive, while Recall denotes the proportion of correctly identified positive samples among all actual positive samples. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a balanced measure of both indicators.

Furthermore, to obtain stable and reliable evaluation results, both the Macro-average and Weighted-average values are computed on the test set to reflect the model’s classification performance across minority and majority classes. For multi-class classification tasks, the corresponding Confusion Matrix is used for statistical analysis, and the model’s discriminative capability is further assessed by plotting the ROC curve and calculating the AUC (Area Under Curve) value.

4.4. Baselines

To comprehensively verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, multiple baseline models are established for comparison in this experiment.

For traditional machine learning approaches, Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) are selected. These models have been widely applied in early malware detection studies and serve as references to evaluate the improvements brought by deep learning methods. Among deep learning models, TextCNN and BiLSTM are chosen. TextCNN is effective in capturing local patterns, while BiLSTM is capable of modeling sequential dependencies. Additionally, a hybrid TextCNN–BiLSTM model is employed to analyze the effectiveness of combining local and global feature representations.

In terms of data augmentation strategies, two common approaches are adopted for comparison. The SMOTE oversampling method balances class distributions by interpolating minority class samples in the feature space. The simple perturbation augmentation method generates variant samples by replacing or inserting noise into the original API call sequences. These approaches are compared against the proposed CWGAN-GP-based data augmentation method and the TextCNN–Transformer hybrid detection framework, to validate the advantages of the proposed method in terms of detection accuracy and generalization capability.

4.5. Experimental Results

4.5.1. Multi-Class Classification Without Data Augmentation

In this subsection, we first evaluate the Mal-TTN detection model without the data augmentation module on the Alibaba Cloud security dataset. The experimental results are shown in

Table 5.

In the eight-class classification task without augmentation, the model performs well on majority classes such as Normal, Ransomware Virus, and Infective Virus, achieving F1-scores of 0.9698, 0.9246, and 0.9584, respectively. However, the performance on minority classes is significantly poorer. For instance, the Worm Virus category, which contains only 100 samples, has Precision, Recall, and F1 values close to 0, indicating that the model is nearly unable to identify it. The F1-scores of Backdoor Program and Trojan Program are only 0.6145 and 0.6348, respectively, showing that the model’s generalization ability is severely limited under class imbalance and data scarcity. Overall, the macro-average F1 is only 0.7068, revealing clear performance discrepancies across different categories.

4.5.2. Multi-Class Classification with Data Augmentation

Next, we apply the Mal-CGP-TTN detection model, which incorporates the CWGAN-GP-based data augmentation strategy, on the same dataset. The results are presented in

Table 6. After data augmentation, the model’s overall performance improves significantly. The categories

Normal,

Ransomware Virus,

Mining Program, and

Infective Virus all achieve Precision and Recall values above 0.95, with the F1-score of

Normal reaching as high as 0.9985—nearly perfect classification accuracy.

Compared to the non-augmented results, the F1-score of Worm Virus improves to 0.38, while those of Backdoor Program and Trojan Program increase to 0.71 and 0.79, respectively. The macro-average F1 rises to 0.827, indicating that data augmentation effectively enhances the model’s recognition capability for minority classes.

Despite these improvements, minority classes such as Worm Virus still exhibit low recall (0.25 before augmentation), mainly due to extremely limited sample size and high similarity to other categories, which makes accurate detection challenging. CWGAN-GP data augmentation partially alleviates this by generating additional class-consistent samples, helping the model better capture distinctive behavioral patterns. However, extremely underrepresented classes remain difficult to classify correctly, highlighting potential areas for further improvement.

To assess the model’s behavior under class imbalance, we compared the confusion matrices of Mal-TTN (without augmentation) and Mal-CGP-TTN (with CWGAN-GP augmentation) on the Alibaba Cloud security dataset, as shown in

Figure 8. Without data augmentation, the model performs well on majority classes but shows clear misclassification in several minority categories. After introducing CWGAN–GP-based data augmentation, the prediction patterns become significantly more concentrated along the diagonal. Correct classifications increase for all classes, with notable gains in minority categories. For example, class 3 (DDoS Trojan), originally represented by only 820 samples, improves from 130 to 151 correct predictions; class 7 (Trojan Program), with 1489 samples, improves from 155 to 230; and the minority class 4 (Worm Virus), originally with only 100 samples, shows reduced dispersion and fewer misclassified outputs. These improvements reflect a substantial enhancement in minority-class discrimination.

These results demonstrate that the augmented samples effectively improve class balance during training and strengthen the model’s ability to learn distinctive behavioral patterns for minority classes. The clearer diagonal structure confirms that data augmentation substantially enhances robustness and class-wise detection performance across the entire label space.

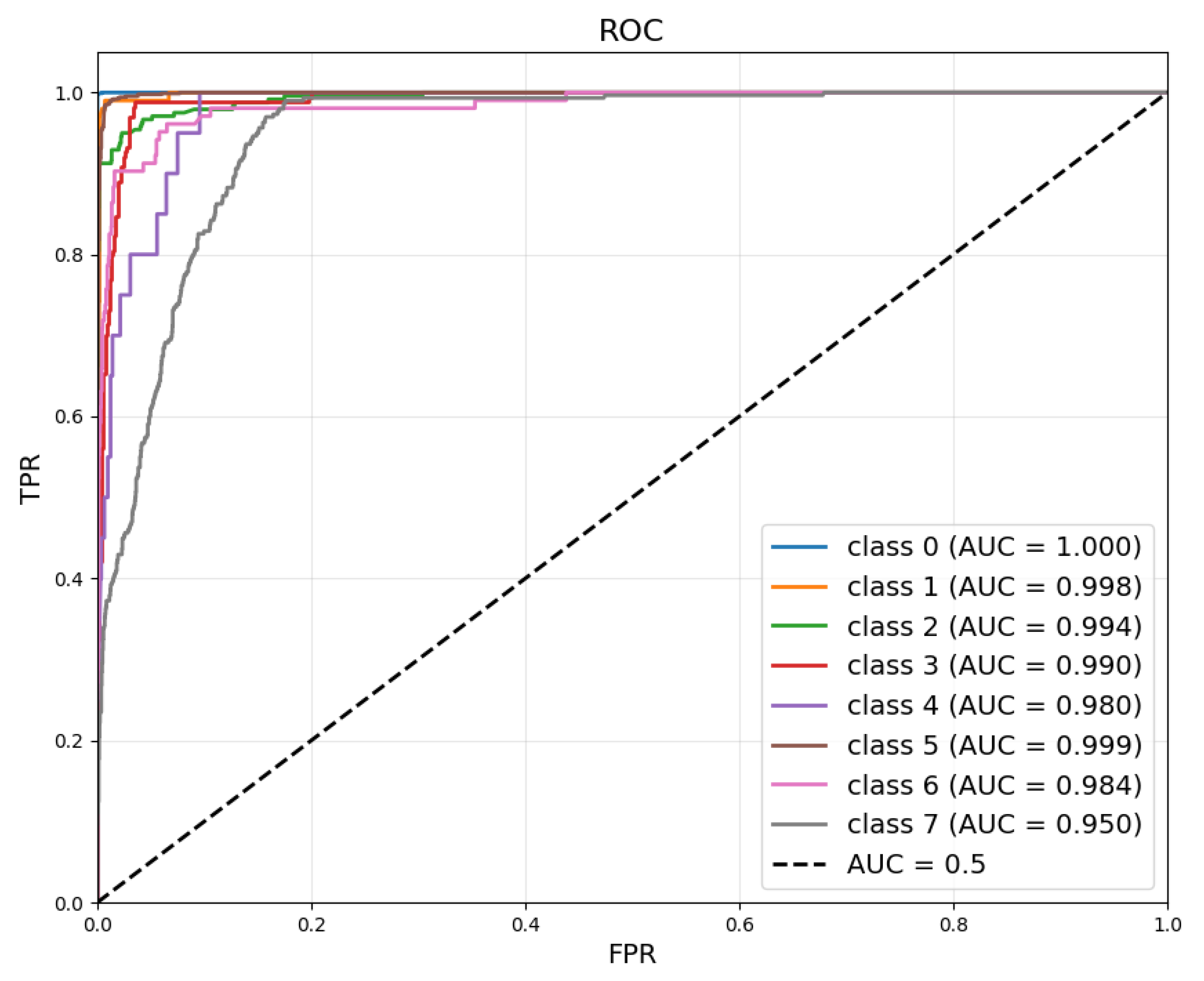

Finally, we analyze the model’s discriminative ability using ROC and AUC curves, as shown in

Figure 9. Most categories achieve AUC values close to 1.0, with

Normal,

Ransomware Virus, and

Infective Virus reaching 1.000, 0.998, and 0.999, respectively, indicating excellent separability.

Mining Program and

DDoS Trojan also achieve AUC of 0.994 and 0.990, showing strong classification performance. In contrast, due to the behavioral similarity among

Backdoor Program,

Trojan Program, and other malware families, their AUC values are slightly lower at 0.984 and 0.950, respectively. Although

Worm Virus reaches an AUC of 0.980, its limited sample size causes larger prediction fluctuations during evaluation.

4.6. Performance Comparison

4.6.1. Binary Classification Experiment Comparison on the Alibaba Cloud Security Dataset

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method in malware detection tasks, we conducted comparative experiments using multiple baseline methods as well as other researchers’ approaches.

Table 7 summarizes the experimental results of different models on the binary classification task. Overall, deep learning methods outperform traditional machine learning algorithms, and the proposed model achieves the best performance across all evaluation metrics.

Among the baselines, the performance of SVM is relatively limited. Within deep learning models, TextCNN outperforms BiLSTM in classification accuracy, while their hybrid TextCNN–BiLSTM model does not bring further improvement and performs slightly lower than the standalone convolutional structure.

For other researchers’ approaches, the API_GAF+CNN method converts API call sequences into Gramian Angular Fields (GAF) images and utilizes convolutional networks for classification. This visual modeling strategy improves detection performance to some extent, validating the feasibility of image-based feature representation. The API Weighting+BiLSTM method assigns feature-level weights to evasion-related APIs and combines TF-IDF with recurrent modeling, enhancing the recognition of adversarial samples. The MalDMTP approach, based on multi-level graph pooling and multi-head attention, learns the API call graph structure, showing an advantage in capturing global dependencies and complex relational interactions.

Compared with these methods, the proposed Mal-TTN and Mal-CGP-TTN models demonstrate superior performance in binary classification tasks. Even without data augmentation, Mal-TTN already surpasses all other models, while with the introduction of semantic data augmentation via CWGAN-GP, Mal-CGP-TTN further improves all metrics significantly.

4.6.2. Multi-Class Classification Experiment Comparison on the Alibaba Cloud Security Dataset

As shown in

Table 8, we further conducted comparative experiments on an eight-class classification task, including various baseline models, previously proposed approaches, and different data augmentation strategies. Overall, multi-class classification is significantly more challenging than binary classification, particularly under class imbalance conditions, where the performance of traditional and some deep learning models generally declines.

Among the baselines, SVM and RF exhibit limited performance, with F1-scores of 0.8113 and 0.8556, respectively, reflecting the inadequacy of traditional machine learning methods in complex multi-class scenarios. Deep learning baselines perform generally better than traditional approaches. TextCNN achieves an F1-score of 0.8625, significantly outperforming BiLSTM (0.8206), suggesting that convolutional architectures are more effective in capturing local patterns and salient behavioral features in malware detection. Although BiLSTM can model long-term dependencies, its performance suffers from gradient vanishing and feature sparsity in long sequences. The combined TextCNN–BiLSTM model further improves performance, reaching an accuracy of 0.8705, outperforming single-structure models.

Among other researchers’ methods, malDetct II-Dense, an improved CNN-LSTM-based model, shows certain advantages in classification but achieves only 0.8505 accuracy overall. The N-gram-XGBoost method attains 0.9030 accuracy, higher than most deep learning models, but does not report other metrics such as F1-score or AUC, making comprehensive evaluation difficult. Furthermore, its reliance on manually crafted features limits adaptability to diverse malware behaviors.

In terms of data augmentation strategies, Mal-RO-TTN employs random oversampling to expand minority classes, achieving an F1-score of 0.8743. While this mitigates class imbalance to some extent, the duplicated samples lack new feature representations and semantic structure, offering limited generalization improvement. Mal-SMOTE-TTN adopts an interpolation-based oversampling strategy in the feature space, achieving an F1-score of 0.8803, outperforming random sampling. This result demonstrates that reasonable data balancing can enhance minority class recognition. However, since SMOTE generates samples through linear combinations, the resulting data lack temporal dependencies and semantic richness.

The proposed Mal-TTN detection model integrates a hybrid architecture of TextCNN and Transformer-Encoder, capturing both local behavioral patterns and global dependencies. Without data augmentation, Mal-TTN achieves an accuracy of 0.8881, outperforming all baselines and comparative models. Upon incorporating the CWGAN-GP-based data augmentation strategy, minority classes are further expanded, enhancing data diversity and forming the augmented version Mal-CGP-TTN. In the eight-class task, Mal-CGP-TTN achieves an accuracy of 0.9467 and an F1-score of 0.9467, significantly outperforming all other methods. These results demonstrate that semantic data augmentation not only effectively alleviates class imbalance but also enhances the model’s ability to learn distinct behavioral patterns among malware categories, thereby comprehensively improving detection performance.

4.6.3. Comparison of Multi-Class Classification Experimental Results on the mal-api-2019 Dataset

To further verify the generalization and robustness of the proposed model, we conducted multi-class classification experiments on another public dataset. By validating the model under different data sources and behavioral patterns, we aim to more comprehensively evaluate its detection capability in diverse malware scenarios.

Catak et al. [

34] performed dynamic analysis on Windows malware samples using the Cuckoo Sandbox and annotated them through VirusTotal, ultimately constructing and publishing the benchmark dataset mal-api-2019. This dataset covers various representative types of malware, containing a total of 7107 API call sequences involving 342 distinct Windows system calls. Based on behavioral characteristics, the samples are divided into eight categories:

spyware,

downloaders,

trojans,

worms,

adware,

droppers,

viruses, and

backdoor malware. The detailed sample distribution is shown in

Table 9.

The mal-api-2019 dataset was randomly divided into training and testing subsets with a ratio of 4:1 using a stratified sampling strategy to maintain class balance. Subsequently, data augmentation was applied to the training set, expanding each class to 1000 samples, while keeping the test set unchanged. The augmented training set thus contains a total of 8000 samples. Model performance on this dataset was evaluated using Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and AUC metrics.

To assess the proposed model’s generalization and stability under different data environments, we compared it with multiple baseline models and existing research methods. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 10.

Overall, traditional machine learning methods show limited capability in modeling complex semantic relationships, with accuracies of 0.5578 (SVM) and 0.5909 (RF). Among deep learning models, TextCNN performs the best, achieving an accuracy of 0.6328, indicating that convolutional structures are effective in extracting local contextual patterns. In contrast, BiLSTM demonstrates weaker performance, with an F1-score of only 0.4041. The hybrid TextCNN–BiLSTM structure yields a slight improvement over BiLSTM but does not surpass the single TextCNN model.

Regarding other research approaches, the Transformer achieves moderate results (accuracy and F1 both 0.5300), showing some advantage in capturing long-range dependencies. The CNN-LSTM model reports the highest accuracy (0.8847), but its F1-score is only 0.2483, indicating severe class imbalance where the model performs well on majority classes but poorly on minority ones. The CAFTrans model integrates one-dimensional channel attention and a frequency enhancement module within the Transformer encoder, effectively improving feature correlation and embedding representation. It achieves an F1-score of 0.6525 and an AUC of 0.8913, making it one of the best publicly reported methods on this dataset.

Under the same experimental conditions, our proposed Mal-TTN model achieves an accuracy of 0.6377 and an AUC of 0.9133 without data augmentation, comparable to CAFTrans. After applying the proposed CWGAN-GP-based semantic data augmentation, the Mal-CGP-TTN model achieves substantial improvements across all metrics, with accuracy and F1-score reaching 0.6732 and 0.6714, respectively, and AUC increasing to 0.9262—significantly outperforming all baseline methods.

The cross-dataset evaluation further demonstrates that the proposed Mal-CGP-TTN model achieves strong generalizability and does not rely excessively on the synthetic samples generated by CWGAN-GP. The consistent performance gains across heterogeneous datasets indicate that the augmentation framework effectively captures semantically meaningful and transferable malicious behavior patterns. These results show that the generated sequences enhance the model’s ability to recognize diverse malware variants rather than leading to overfitting to dataset-specific characteristics, thereby improving both robustness and practical applicability.

4.7. Ablation Experiment

To deeply analyze the contributions of the data augmentation module and feature extraction module to model performance, we conducted ablation experiments on the Alibaba Cloud Security dataset. Different model configurations were designed in the ablation experiments to evaluate the impact of each module on model performance, and the experimental results are presented in

Table 11, Transformer-Encoder alone achieves 0.8205 accuracy and 0.8170 F1-score, indicating that global features alone are insufficient for capturing fine-grained malware patterns. In contrast, TextCNN alone reaches 0.8622 accuracy and 0.8625 F1-score, demonstrating the importance of local feature extraction. Applying data augmentation improves TextCNN to 0.9073 accuracy and 0.9054 F1-score, and Transformer-Encoder to 0.8602 accuracy and 0.8570 F1-score, showing that synthetic samples mitigate data scarcity and imbalance, with stronger gains for TextCNN due to its higher baseline. Combining both feature extractors without augmentation (Mal-TTN) yields 0.8881 accuracy and 0.8832 F1-score, confirming that integrating global and local features enhances representation. Finally, the full Mal-CGP-TTN model achieves 0.9467 accuracy and 0.9467 F1-score, demonstrating that the joint use of comprehensive feature extraction and data augmentation substantially improves multi-class classification performance.

4.8. Robustness Evaluation

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed Mal-CGP-TTN model against perturbed or obfuscated inputs, we conducted a supplementary assessment on the Alibaba Cloud security dataset using test sequences modified to simulate common malware evasion behaviors. Specifically, we designed two types of perturbations to mimic realistic anti-detection techniques while preserving the original functionality of the malware samples.

The first type is rule-based obfuscation, which manipulates the structure of API call sequences through three specific operations. First, insertion of benign API calls adds harmless function calls at strategic positions to confuse pattern-based detection methods. Second, local reordering of existing API calls swaps the order of nearby calls without changing the overall logic, simulating common code obfuscation practices. Third, mild deletion of redundant API invocations removes non-essential repeated calls, which can occur naturally or be introduced by malware authors to evade signature-based detectors. These operations collectively introduce structural variability in the sequences while maintaining their original behavior.

The second type is embedding-level adversarial perturbation, which targets the model’s input representation rather than the sequence itself. Small-magnitude perturbations are generated using the FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method) and applied directly to the embedding vectors of the API calls. This technique slightly shifts the feature representation in the embedding space, challenging the model to make correct predictions under subtle, semantic-preserving noise. Unlike rule-based obfuscation, this approach does not modify the sequence of API calls, but rather simulates sophisticated evasion attempts at the feature level.

As shown in

Table 12, the Mal-CGP-TTN model maintains consistently high performance under all perturbation settings. When subjected to mild rule-based obfuscation, its accuracy decreases only from 0.9467 to 0.8965, and even under moderate obfuscation it still achieves 0.8821. A similar trend is observed for embedding-level adversarial perturbations: the model retains 0.8744 accuracy under FGSM with

, and remains as high as 0.8590 under the strongest perturbation (

). These results show that Mal-CGP-TTN consistently preserves over 85% accuracy despite relative drops of only 5–9%, demonstrating that its learned representations are robust to both structural obfuscation and embedding-level adversarial noise. Overall, the experimental evidence confirms that the integration of CWGAN-GP-based semantic data augmentation with hybrid global–local feature extraction significantly enhances the model’s resilience, ensuring reliable detection capability even in adversarial or obfuscated malware environments.

Since the primary contributions of this work focus on data augmentation and hybrid sequence modeling, a comprehensive study of adversarial robustness is left for future work.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses two major challenges in malware detection: the detection bias caused by class imbalance and the limited recognition performance resulting from insufficient feature extraction. To tackle these issues, we proposed a malware detection model named Mal-CGP-TTN, which integrates a CWGAN-GP-based data augmentation strategy with an TextCNN–Transformer hybrid detection framework. Specifically, the proposed approach first employs a Conditional Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (CWGAN-GP) to generate semantically consistent and diverse samples for minority classes, thereby alleviating the imbalance in training data distribution. Then, by combining the TextCNN and Transformer-Encoder structures, the model achieves a collaborative fusion of local behavior pattern extraction and global dependency modeling, significantly enhancing feature representation and classification performance. Furthermore, the robustness evaluation under obfuscation-based and embedding-level perturbations confirms that the proposed framework maintains stable performance even in adversarial or obfuscated malware environments, highlighting its practical applicability in real-world detection scenarios.

Although the proposed method demonstrates substantial improvements in detection performance, there remains room for further research. The generative model may still experience mode collapse when capturing the complex semantic structures of extremely rare samples; future work can explore hybrid generation strategies combining diffusion models to improve generation quality. Moreover, the current work mainly focuses on behavioral modeling at the API call sequence level, which limits feature diversity. Future research could incorporate Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or multimodal fusion mechanisms to integrate static file structure information, system call graphs, and network traffic features, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to represent multi-source malicious behaviors. In addition, exploring online detection and continual learning mechanisms would allow the model to adapt to the dynamic evolution of malware, ensuring both real-time detection performance and long-term adaptability.