1. Introduction

With the continuous expansion of network infrastructures, the security challenges confronting computer networks have become increasingly severe. Network traffic anomaly detection serves as a critical mechanism for ensuring network stability and performance. By monitoring and analyzing network traffic data in real time, potential network disruptions and anomalous behaviors can be promptly identified, thereby enhancing the overall reliability of computer networks. In this context, anomaly detection serves as the core technical methodology, identifying statistical deviations from a learned baseline of normal behavior. These anomalies, or statistical deviations, can represent significant network events, such as flash crowds, equipment failures, or novel traffic patterns that differ from the norm. Effectively identifying them is critical for network monitoring and management. Emerging network phenomena, such as high-volume traffic events (e.g., flash crowds or DDoS events), can render critical infrastructure services unavailable by exhausting system resources, potentially resulting in significant economic losses. Although traditional security mechanisms are widely deployed, the evolution of attack vectors and the expansion of the attack surface have given rise to cyber threats that are increasingly large-scale, persistent, and destructive. Traditional machine learning methods, such as Decision Trees (DTs) [

1], Naive Bayes (NB) [

2], and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [

3], typically rely on the manual extraction and analysis of traffic features based on expert knowledge to build models. However, these methods possess a limited capacity to capture intricate data patterns and consequently struggle to address the increasingly complex traffic modeling challenges [

4].

Deep learning methods offer novel approaches to network traffic anomaly detection by leveraging their powerful capabilities in automatic feature extraction and high-dimensional data modeling. Through multi-layered neural network architectures, deep learning models automatically extract data features via nonlinear transformations, thereby addressing the shortcomings inherent in traditional machine learning methods [

5,

6,

7]. For instance, Althubiti et al. [

8] employed a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) recurrent neural network classifier for traffic classification tasks. Their experimental results on the KDDCup99 dataset demonstrated that the LSTM classifier outperformed several high-performing traditional classifiers. Similarly, Li et al. [

9] proposed an accurate anomaly detection method based on pseudo-anomaly injection, featuring an efficient feature extraction framework and a novel Denoising Autoencoder-Generative Adversarial Network (DAE-GAN) model. Their framework utilized an innovative packet-windowing technique to extract both spatial and temporal features from network traffic. More recently, complex architectures have demonstrated significant potential. Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based methods, for instance, can effectively capture anomalous traffic interactions within the network topology [

10]. Concurrently, Transformer-based models leverage their self-attention mechanism to learn long-term dependencies in traffic sequences, also showing great promise for anomaly detection tasks [

11]. In another study, Wang et al. [

12] introduced an anomalous flow detection system based on a hybrid deep learning model capable of rapidly locating the source of the anomalous flow. Compared to SDN-based anomaly detection methods, the proposed method significantly enhances fine-grained detection by utilizing multidimensional features.

Despite these advances, deep learning methods still face the challenge of data imbalance in traffic anomaly detection, resulting in low detection rates for minority-class attacks. When normal traffic samples far exceed anomalous traffic in volume, the model tends to classify most inputs as the majority (normal) class. This leads to poor detection performance for critical minority attack classes—an outcome that is unacceptable in real-world network monitoring scenarios [

6]. Zhou et al. [

13] proposed a traffic anomaly detection method that combines an Autoencoder (AE) and a residual neural network. In their approach, the autoencoder first reconstructs the input data for feature extraction, and these features are subsequently used to train the residual network. While this method improved model performance, it failed to account for the imbalanced nature of the data, consequently causing the model to overfit the majority class while underfitting minority classes.

Traditional rule-based monitoring methods are often ineffective against novel, unforeseen anomaly types due to their reliance on pre-defined signatures. In contrast, anomaly-based detection, which compares network activity against established normal behavior patterns, offers a more flexible approach, though it can suffer from high false positive rates if the “normal” baseline is not modeled accurately.

Among the most prominent datasets in this field is the KDDCup99 dataset, which has served as a benchmark in numerous studies [

14,

15]. It was followed by an enhanced version, NSL-KDD, which has also been extensively studied in the literature [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The NSL-KDD dataset improved upon its predecessor by removing redundant records to create a more balanced sample distribution, establishing it as a more suitable evaluation benchmark. As a result, it has been widely used to validate the performance of various algorithms [

21]. However, it is crucial to note that the NSL-KDD dataset is derived from network traffic captured over two decades ago. Therefore, it fails to represent modern cyberattack techniques, such as Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), attacks over encrypted traffic, or emerging threats within the Internet of Things (IoT) ecosystem [

22]. This limitation means that high performance achieved by models on the NSL-KDD dataset does not necessarily translate into effective defense capabilities in contemporary network environments [

23]. This disparity underscores the critical need for evaluation using more recent and diverse datasets, such as CICIDS2017. While the CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15 datasets were originally curated for intrusion detection research, in this study, they serve as standard, publicly available benchmarks for network traffic anomaly detection. This is due to their realistic, imbalanced distribution and, most importantly, their clearly labeled classes of non-normal (anomalous) traffic, which allows for a robust evaluation of the proposed methodology in classifying rare, deviant behavior.

Cui et al. [

24] proposed a novel multi-module integrated intrusion detection system that utilizes stacked autoencoders for feature extraction. Their method addresses data imbalance by combining a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) with a Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) and employs a CNN and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network for classification. While this approach effectively reduced the model’s false alarm rate, WGANs are susceptible to mode collapse and training instability during sample generation. To mitigate the instability challenges associated with GAN training, researchers have explored alternative data augmentation strategies. For instance, Variational Autoencoder (VAE)-based approaches generate high-quality minority samples by learning the latent distribution of data, offering a more stable training process [

25]. Other studies have adopted self-supervised learning paradigms, such as contrastive learning, to enhance a model’s ability to distinguish between normal and anomalous traffic. This is achieved by learning effective representations from unlabeled data, thereby mitigating the impact of data imbalance without direct sample generation [

26].

Beyond data-level solutions, improvements at the optimization algorithm level are also critical for enhancing model performance. When processing complex and high-dimensional network traffic data, a model must not only fit the training data but also generalize well to unseen data to effectively counter continuously evolving attack methods.

Foret et al. [

27] proposed the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) algorithm, which enhances model generalization. Instead of seeking parameters that simply minimize the training loss (a sharp minimizer), SAM identifies parameters within a neighborhood characterized by uniformly low loss values (a flat minimizer). In summary, although the aforementioned methods have achieved commendable detection results, the majority still struggle with the challenge of data imbalance, resulting in poor detection rates for minority classes. To address these persistent challenges, this paper proposes a deep learning framework for anomaly detection in imbalanced network traffic.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

We propose a novel and effective flow detection model, ResCAE-BiGRU. This model extracts multi-scale spatial features using a split residual structure and captures bidirectional temporal dependencies via a BiGRU layer. By integrating the advantages of ResNet and Autoencoder architectures and employing the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) optimizer, the model significantly enhances generalization and improves the detection rate of minority anomaly classes.

We introduce a data preprocessing pipeline that first utilizes the Isolation Forest algorithm to remove outliers from the majority (normal) class, thereby sharpening the decision boundary. Subsequently, the SMOTE-Tomek technique is applied to synthesize high-quality minority class samples, addressing the data imbalance problem while enhancing sample diversity and bolstering the model’s detection capabilities for rare anomalies.

We conduct a rigorous evaluation of the proposed model on the CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15 datasets, which contain diverse and realistic modern cyber threats. The proposed model’s superiority is demonstrated through extensive comparative experiments with existing state-of-the-art methods. Performance is rigorously assessed using standard metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, confirming the effectiveness and robustness of our ResCAE-BiGRU method.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Model Framework

The primary objective of anomaly traffic detection methods is to achieve superior performance in identifying malicious traffic, particularly in scenarios with a limited number of attack samples. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the proposed framework comprises two main components: a data processing module and a traffic detection module. The Input block in the diagram represents the raw network traffic traces (e.g., from the CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15 datasets), which are detailed in

Section 3.5.1. The data processing module initially conducts numerical conversion, outlier removal, and data normalization. Initially, normal class samples are processed using the isolated forest method. Subsequently, to address class imbalance, additional minority attack class samples are synthesized using the SMOTE-Tomek technique, which preserves the consistency of the original data distribution. The traffic detection module features a traffic anomaly detection model based on a Residual Convolutional Autoencoder and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (ResCAE-BiGRU) architecture. This model first employs the split residual structure of the ResCAE to extract multi-scale spatial features. Subsequently, the BiGRU captures bidirectional temporal dependencies from the data. To enhance the model’s generalization capability, the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) method is integrated into the training stage alongside the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer, thereby improving the detection rate of minority attack samples. Finally, the model’s performance was evaluated using standard metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The proposed method was tested on the CICIDS2017 dataset to verify its efficacy.

3.2. Data Processing

3.2.1. Numerical Conversion

Different encoding strategies are utilized for features and labels. First, non-numerical categorical features in the dataset are processed using the One-Hot Encoding technique. This method converts each categorical feature containing N unique categories into N new binary features. This transformation effectively maps the categorical text labels into a high-dimensional vector space, enabling the model to process these non-numeric features while avoiding the introduction of artificial ordinal relationships. Secondly, Label Encoding is employed to transform the model’s prediction target, the network traffic attack labels. This technique maps each unique string label to a unique integer. This transformation is necessary for the calculation of the loss function during model training.

3.2.2. Outlier Processing

In real-world network environments, data may contain anomalous values or outliers resulting from factors such as traffic bursts or data collection errors. To address this, the Isolation Forest (iForest) [

31] algorithm is employed for outlier detection and removal. To prevent the risk of removing rare but valid malicious samples, this outlier removal process is applied exclusively to the BENIGN (normal) class samples within the training set. All minority attack class samples are explicitly excluded from this step. The specific process is as follows:

A random subsample of size ψ is drawn from the training dataset to form the root node of an isolation tree (iTree).

At the current node, a feature is randomly selected. A split value, p, is then randomly chosen between the minimum and maximum values of that feature for the data points within the node. The node’s data is then partitioned into two child nodes based on this split.

The partitioning process from Step 2 is repeated recursively for each child node. This continues until a node contains only a single data point, or a predefined maximum tree depth is reached.

Steps 1 through 3 are repeated to construct a specified number, t, of iTrees, thus forming an ensemble known as an “isolation forest”.

To normalize path lengths, an average path length for a dataset of size n, denoted as c(n), is used as a normalization factor. The formula for c(n) is:

where

H(

i) is the harmonic number, which can be approximated by

,

≈ 0.577 is the Euler-Mascheroni constant.

- 6.

To obtain an anomaly score for a data point x, it is passed through the trained forest. The path length, h(x), is measured for each iTree, and the average path length across all trees, E[h(x)], is computed. The final anomaly score, s(x,n), is then calculated as follows:

where

E[

h(

x)] is the average path length (expected value) of sample

x across all iTrees. An anomaly score close to 1 indicates a high likelihood of being an outlier, while a score much smaller than 0.5 suggests the point is likely normal.

3.2.3. Normalization

To address issues arising from disparate feature scales, we employ Min-Max Normalization. This technique rescales the range of each feature to a specific interval, typically [0, 1], thereby ensuring that all features contribute more equally to the model’s training process and mitigating potential biases. The formula for Min-Max normalization is as follows:

where

x is the original feature value, and

and

are the minimum and maximum values of that feature in the dataset, respectively. The resulting value,

, represents the scaled feature.

To prevent data leakage, the normalization process is applied after the dataset has been partitioned into training and validation sets. The MinMaxScaler is first fit only on the training data, and the parameters learned from the training data (i.e., its min and max values) are then applied to transform the validation set.

3.2.4. SMOTE-Tomek Process

SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) is a widely used technique for addressing class imbalance in datasets [

32]. The fundamental principle of SMOTE is to generate synthetic instances of the minority class to create a more balanced dataset. The algorithm operates by first randomly selecting a minority class instance,

x, from a few categories set

C. It then identifies the k nearest neighbors of

x within the same class, typically using the Euclidean distance. Next, a synthetic sample,

, is generated by interpolating between the selected instance x and one of its randomly chosen nearest neighbors, as described in Equation (11). In this equation,

α is a random value drawn from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1, which ensures the synthetic sample lies along the line segment connecting the original instance and its selected neighbor.

where:

is the newly generated synthetic sample.

x is the original sample selected from the minority class.

is the randomly chosen k-nearest neighbor of x.

α is a random number in the interval [0, 1].

The SMOTE algorithm effectively mitigates the overfitting problem associated with random oversampling methods. While SMOTE offers a novel approach to addressing data imbalance, it possesses inherent limitations. Specifically, the synthesis of new samples is determined entirely by the selection of a root sample and one of its minority class neighbors. A key drawback is that this synthesis process operates without consideration for the distribution of the majority class. If both the root sample and its selected neighbor are situated within a dense region of the minority class, the resulting synthetic sample is likely to be appropriately positioned. Conversely, if either the root sample or its neighbor is an outlier, the resulting synthetic instance may be generated in a region dominated by the majority class, causing the new minority sample to encroach upon the majority class space.

To address the issues of class overlap and blurred decision boundaries caused by the standard SMOTE algorithm, this study utilizes the hybrid SMOTE-Tomek method to mitigate the data imbalance problem. The methodology first employs the SMOTE algorithm to generate synthetic minority class samples. Subsequently, the Tomek Links [

33] algorithm is applied to cleanse the augmented dataset by removing existing Tomek Link pairs. This two-step process effectively eliminates noise and overlapping instances near the class boundary. In our data processing workflow, the initial dataset is partitioned into training and validation sets at a 7:3 ratio. The SMOTE-Tomek procedure is then applied exclusively to the minority class within the training set. This yields a balanced and refined training dataset, which is subsequently shuffled prior to being used for model training.

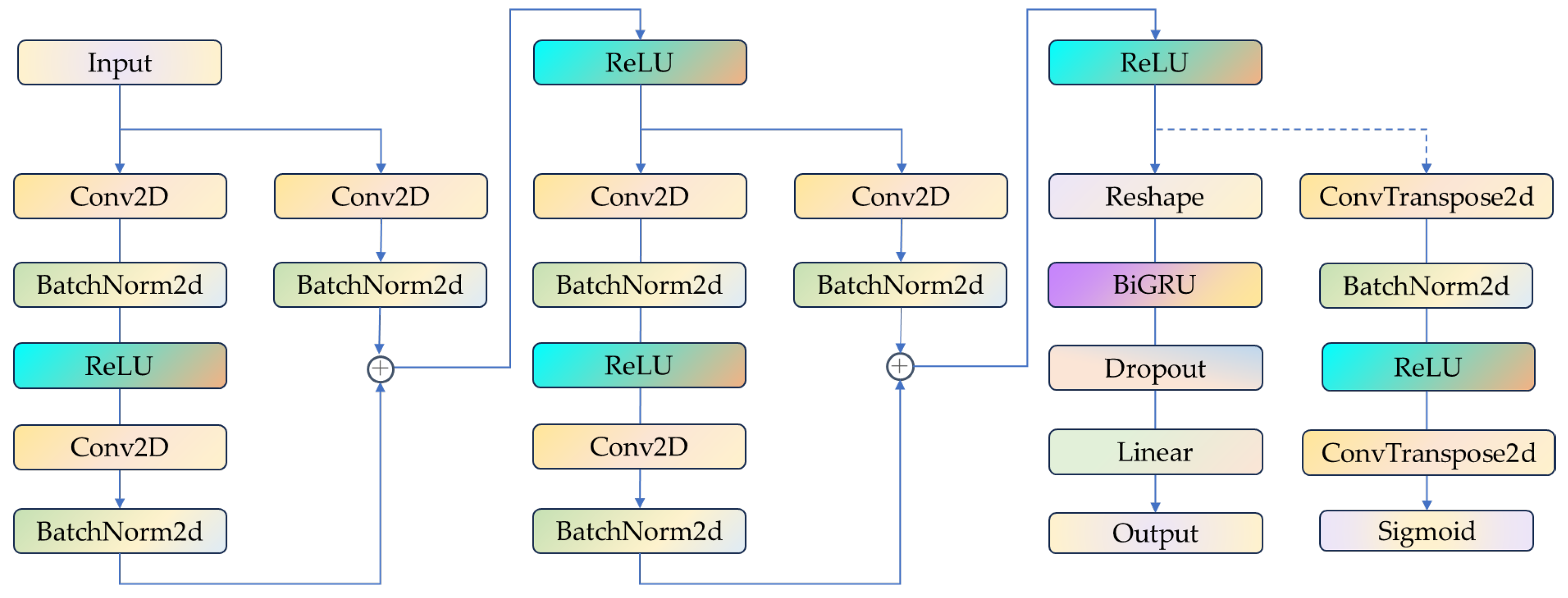

3.3. The ResCAE-BiGRU

The proposed ResCAE-BiGRU model for abnormal flow detection comprises three primary components, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The detailed layer-wise configuration of the ResCAE-BiGRU architecture is provided in

Table 1. The architectural flow, as depicted in

Figure 3, proceeds as follows:

ResCAE Feature Extraction: The preprocessed traffic data is fed into the ResCAE module, which utilizes two residual blocks to perform convolution operations. This process extracts multi-scale spatial features and progressively reduces dimensionality, yielding the encoded hidden layer feature vector, denoted as h.

Reshaping: The hidden layer feature vector h is reshaped. This conversion adapts the 4-dimensional format (N, C, H, W), which is required by the Conv2d layers used in our ResCAE, into the 3-dimensional sequential format (N, L, H_in) required by the BiGRU module by employing squeeze and permute operations.

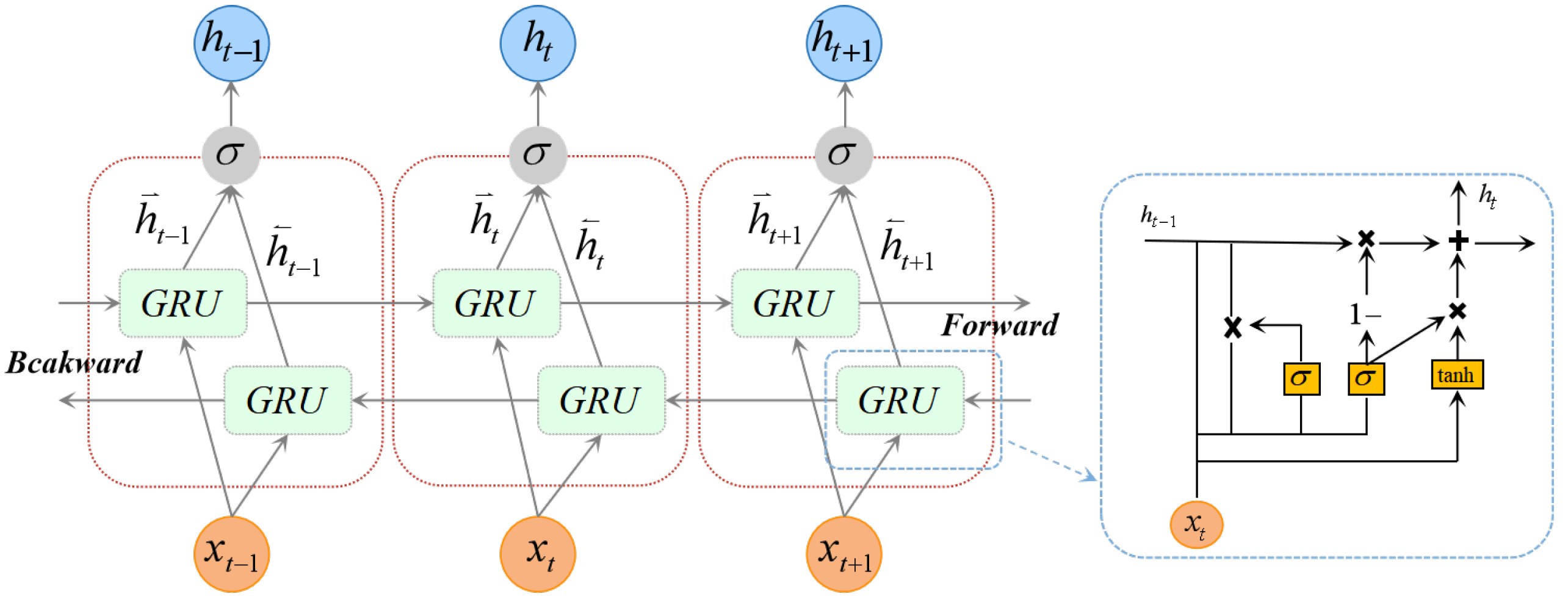

BiGRU Temporal Processing: The reshaped sequential features are then input into the BiGRU module, which processes the sequence bidirectionally to capture both forward and backward temporal dependencies. This results in the final output feature representation, h′.

Classification: This feature representation h′ is passed through a Dropout layer and a fully connected (Linear) layer employing a Softmax activation function to perform traffic classification, thereby achieving anomaly detection.

Figure 3.

The proposed ResCAE-BiGRU models architecture.

Figure 3.

The proposed ResCAE-BiGRU models architecture.

Table 1.

ResCAE-BiGRU network architecture details.

Table 1.

ResCAE-BiGRU network architecture details.

| Layer Name | Layer Type | Hyperparameters |

|---|

| RB1_path1_conv1 | Conv2d Layer | Filters: 16, Kernel size: 3, Stride: 2, Padding: 1, Activation: ReLU |

| RB1_path1_bn1 | Batch Normalization | Applied to the output of conv1 |

| RB1_path1_conv2 | Conv2d Layer | Filters: 16, Kernel size: 3, Stride: 1, Padding: 1, Activation: ReLU |

| RB1_path1_bn2 | Batch Normalization | Applied to the output of conv2 |

| RB1_path2_conv1 | Conv2d Layer | Filters: 16, Kernel size: 1, Stride: 2, Padding: 1, Activation: ReLU |

| RB1_path2_bn1 | Batch Normalization | Applied to the output of conv1 |

| RB2 | ResidualBlock | The structure of RB2 is the same as RB1, but with 32 filters. |

| ConvTranspose2d | ConvTranspose2d Layer | Filters: 16, Kernel size: 3, Stride: 2, Padding: 1, Activation: ReLU |

| ConvTranspose2d | ConvTranspose2d Layer | Filters: 1, Kernel size: 3, Stride: 2, Padding: 1, Activation: Sigmoid |

| BiGRU | BiGRU Layer | Input size: 32, hidden size: 64, layers: 2, bidirectional: True |

| Dropout | Dropout Layer | Dropout Rate: 50% |

A critical aspect of our model is the transformation of the 1D input feature vector into a structure suitable for 2D convolution and sequential modeling. After data preprocessing, each network sample is a 1D vector with features. We explicitly reshape this vector into a 4D tensor by adding two dimensions, resulting in an input shape of [Batch_Size, 1, 1, ].

This transformation is the basis for our hybrid approach:

Spatial Feature Extraction (ResCAE): The ResCAE module, which utilizes Conv2d layers, treats the [N, C = 1, H = 1, W = ] input as a 1 × “image”. The 2D convolutional kernels (e.g., kernel_size = 3) slide along the W dimension, capturing local patterns and correlations among adjacent features in the vector. We define this as “spatial” feature extraction, as it learns the relationships within local groups of features (e.g., statistical features related to packet length).

Temporal Dependency Modeling (BiGRU): The ResCAE encoder processes this input, outputting a compressed 4D feature map (e.g., [N, 32, 1, ]). As defined in the ResCAE_BiGRU forward pass, this map is reshaped into a 3D tensor of shape [N, , 32] using squeeze and permute operations. This tensor is then fed to the BiGRU, which interprets it as a sequence of length where each step has 32 features. The “temporal” modeling thus refers to capturing the sequential, contextual dependencies (both forward and backward) along this sequence of CNN-extracted feature patches.

3.4. Model Training Strategy

To enhance the generalization ability of the model, a “Pre-tuning and Fine-tuning” training strategy is employed. During the unsupervised pre-training stage, the complete ResCAE autoencoder architecture is trained to reconstruct its input data. Crucially, this stage utilizes the entire training dataset, which includes both normal and various attack traffic samples, albeit without their corresponding labels. By learning to reconstruct this diverse set of traffic, the encoder is compelled to learn a robust and generalized feature representation that captures the underlying patterns common across all data types. The primary objective of this stage is to learn an effective data representation rather than to perform classification, and it utilizes the Mean Squared Error Loss (MSELoss) function to quantify reconstruction error. The formula for MSELoss is:

where:

n represents the total number of elements in the input vector.

is the value of the i-th element in the original input vector.

is the corresponding value in the output vector reconstructed by the decoder.

Minimizing this loss function compels the encoder to learn a compressed feature representation that retains the core information of the original data, thereby providing high-quality initial weights for the subsequent fine-tuning phase.

The fine-tuning phase commences by loading the pretrained encoder weights into the final ResCAE-BiGRU model. For training the classifier, the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer is augmented with the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) algorithm [

27]. SAM enhances the model’s generalization ability by seeking parameter neighborhoods with uniformly low loss values, thereby improving classification accuracy. This optimization process involves a two-step update strategy.

The first step is to identify points within the parameter neighborhood that yield the steepest increase in loss. Given the current model parameters

w, SAM calculates a perturbation vector,

, that points toward the direction of steepest loss ascent within a defined neighborhood of radius

ρ. The objective is to proactively identify the “worst-case” perturbation in the parameter neighborhood. This perturbation vector is calculated as follows:

where:

S represents the training data set.

w denotes the model parameters.

is the gradient of the loss function with respect to the current parameters w.

ρ is a hyperparameter that defines the size of the neighborhood.

Once the perturbation vector is calculated, the model temporarily updates the parameters to this worst-case position, defined as .

The second step involves performing the main parameter update based on the gradient at this worst-case point. Specifically, the loss function is evaluated at the perturbed position

. The resulting gradient, termed the “adversarial gradient”, is then used to update the original model parameters

w. The final update rule is expressed as follows:

Finally, the SGD optimizer uses this adversarial gradient to perform the gradient descent update on the original model parameters w. Through this two-step “ascent-descent” strategy, SAM guides the SGD optimizer to find not just a minimal loss value, but a broad, flat minimum. Convergence to such a region implies that the model exhibits less sensitivity to minor perturbations in its parameters, consequently demonstrating stronger robustness and improved generalization performance.

The loss function employed in this study is Focal Loss, a modification of the standard cross-entropy loss. Originally proposed by Lin et al. [

34] in their work on RetinaNet, it was designed to solve the problem of extreme class imbalance encountered by deep learning models during training. The core principle of Focal Loss is to modulate the standard cross-entropy loss using a dynamically scaled factor. This factor reduces the contribution of well-classified examples to the total loss, thereby forcing the model to focus on learning from a smaller set of difficult-to-classify samples during training. Specifically, the scaling factor dynamically adjusts the contribution of each sample to the loss based on the model’s predicted confidence. For easily segmented samples with high prediction confidence (i.e., a predicted probability approaching 1), the corresponding loss contribution is significantly reduced. Conversely, for difficult-to-segment samples with low confidence (i.e., a predicted probability approaching 0), the loss contribution remains relatively high.

Focal Loss modifies the cross-entropy loss by introducing a modulating factor,

, which is formulated as follows:

where:

The factor is the core modulating factor.

represents the model’s predicted probability for the ground-truth class. For an easily classified sample where , this factor approaches zero, thereby reducing the sample’s contribution to the total loss. Conversely, for a misclassified sample where , the factor approaches one, leaving the loss value largely unaffected.

is a tunable focusing parameter that adjusts the rate at which easily classified samples are down-weighted. A higher value of intensifies this down-weighting effect. When , the Focal Loss function becomes equivalent to the standard cross-entropy loss.

To further address the imbalance between positive and negative samples, a weighting factor,

, is introduced, which is formulated as follows:

This factor is controlled by the hyperparameter

, which balances the importance assigned to positive and negative classes.

Consequently, the complete Focal Loss formulation addresses class imbalance statically via the term while dynamically managing the imbalance between easy and difficult samples via the term.

3.5. Experiments

3.5.1. Dataset

The CICIDS2017 dataset employed in this study is a network traffic dataset developed through a collaboration between the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) and the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC). While the CICIDS2017 dataset was originally curated for intrusion detection research, in this study, it serves as a standard, publicly available benchmark for network traffic anomaly detection. This is due to its realistic, imbalanced distribution and, most importantly, its clearly labeled classes of non-normal (anomalous) traffic, which allows for a robust evaluation of the proposed methodology in classifying rare, deviant behavior. The dataset comprises network traffic data collected over a one-week period in a real-world environment. This collection includes only normal traffic on Monday, followed by a mixture of normal and various attack traffic types from Tuesday to Friday. In total, the dataset is distributed across eight files, containing 2,813,797 samples, each described by 79 features. Each sample is labeled as either normal or as one of 14 attack types, such as FTP Brute-force, SSH Brute-force, Web Attack, DoS, and Botnets. The CICIDS2017 dataset provides an ideal benchmark for the development and evaluation of anomaly detection models. Each record contains detailed information, including IP addresses, port numbers, and protocol types, and is clearly labeled to distinguish between normal and various attack traffic flows. These properties, including its realistic data and distinct labels, make the CICIDS2017 dataset highly suitable for machine learning and data science projects, particularly in the cybersecurity domain. To mitigate the inherent class imbalance, a subset consisting of 1/4 of the normal data and all attack data was selected for the experiment. The resulting data distribution is detailed in

Table 2.

The UNSW-NB15 dataset was generated using the IXIA PerfectStorm tool at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Canberra to create a hybrid of realistic normal network activities and synthetic contemporary attack behaviors. From this, a total of 100 GB of raw traffic was captured in PCAP format using the tcpdump tool. The dataset encompasses nine distinct attack categories: Fuzzers, Analysis, Backdoors, Denial of Service (DoS), Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance, Shellcode, and Worms. Subsequently, a total of 49 features and their corresponding class labels were extracted using the Argus and Bro-IDS tools in conjunction with twelve feature-extraction algorithms. Compared with the legacy KDD99 dataset, UNSW-NB15 more accurately reflects the traffic characteristics of modern networks and presents a more realistic and balanced data distribution. The class distribution within the UNSW-NB15 dataset is illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.5.2. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, several performance metrics are considered, each representing a specific aspect of classification effectiveness. The selected evaluation indicators include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score.

Accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly classified samples among all samples and is commonly used to assess the overall performance of the model. In this context, True Positive (TP) refers to the number of positive samples correctly identified by the model, False Negative (FN) denotes the number of positive samples incorrectly classified as negative, False Positive (FP) indicates the number of negative samples incorrectly classified as positive, and True Negative (TN) represents the number of negative samples correctly identified by the model.

Precision is used to represent the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive. Recall, on the other hand, indicates the proportion of actual positive samples that are correctly identified by the model. These two metrics are essential for evaluating the model’s classification performance with respect to a specific class.

There is a high likelihood that precision and recall may yield inconsistent results. Therefore, the F1-score is introduced to comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a more balanced and intuitive measure of the model’s classification capability across different categories. This metric is particularly useful when there is an uneven class distribution. The formulas for these evaluation metrics are as follows:

However, in a multiclass imbalanced setting, a single aggregate F1-score (such as Micro F1 or Macro F1) can obscure poor performance on critical minority classes. To address this, our evaluation strategy is two-fold:

Per-Class F1-Score: Our primary evaluation, presented in

Section 4, reports the F1-score for each class individually. We believe this granular, per-class analysis is the most transparent method, as it explicitly reveals the model’s effectiveness (or failure) on specific minority attack classes, which is the core challenge of this research.

For the summary comparison tables, we report the Weighted F1-score. This metric calculates the F1-score for each class and computes a weighted average based on the support for each class.

We chose this Weighted F1-score for aggregation because it reflects the model’s overall performance relative to the dataset’s realistic, imbalanced distribution. We contend that this combination—a transparent per-class breakdown to rigorously assess minority classes, supplemented by a weighted-average score to reflect overall performance on the imbalanced data—provides a more complete and honest evaluation than a single Macro F1-score alone.

3.5.3. Experimental Environment Configuration

The software and hardware configurations of the experimental platform used in this study are shown in

Table 3.

3.5.4. Training Parameter Settings

For optimal model training and performance, the hyperparameters were configured as follows. The model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 256. The optimizer selected was Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) using a Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) base and a learning rate of 0.01. For the two training stages, the pre-training loss function was Mean Squared Error (MSE), and the fine-tuning loss function was Focal Loss. These hyperparameter settings are summarized in

Table 4.

A brief explanation of the above parameters is as follows:

Model training employed a two-stage strategy consisting of pre-training and fine-tuning. In the first stage, the ResCAE module underwent unsupervised pre-training, enabling its encoder to learn a robust and generalized feature representation of the input data. The second stage involved supervised fine-tuning, for which the hyperparameters were configured as follows.

A batch size of 256 was selected to balance gradient stability with available GPU memory resources, with the value being a power of two to optimize hardware utilization.

The Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) optimizer was utilized with a Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) base. This choice was made to guide the model towards flatter loss minima, which is correlated with enhanced generalization capabilities. The base SGD optimizer was configured with an initial learning rate of 0.01 and a momentum of 0.9, while the neighborhood radius for SAM (ρ) was set to 0.05.

To dynamically adjust the learning rate during training, a CosineAnnealingLR scheduler was employed. This scheduler modulates the learning rate over the training epochs according to a cosine function curve. The learning rate begins at a pre-defined maximum and gradually decays to a minimum value over the course of training. This strategy enables the use of a larger learning rate in the initial training phases for rapid exploration of the solution space, and a smaller learning rate in the later stages to facilitate precise convergence near an optimal solution. Training was conducted for a total of 50 epochs, over which the scheduler completed one full annealing cycle to ensure sufficient model convergence.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Performance Evaluation CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15

In real-world online environments, anomalous behaviors often exhibit a degree of stochasticity. Furthermore, such anomalous traffic typically occurs far less frequently than normal traffic patterns, creating an inherent class imbalance. This phenomenon was confirmed in our preceding analysis of the datasets. Therefore, a critical step in evaluating an anomaly detection model is to assess its performance in detecting each distinct type of anomalous behavior. To this end, a per-class performance evaluation is required for each anomaly label.

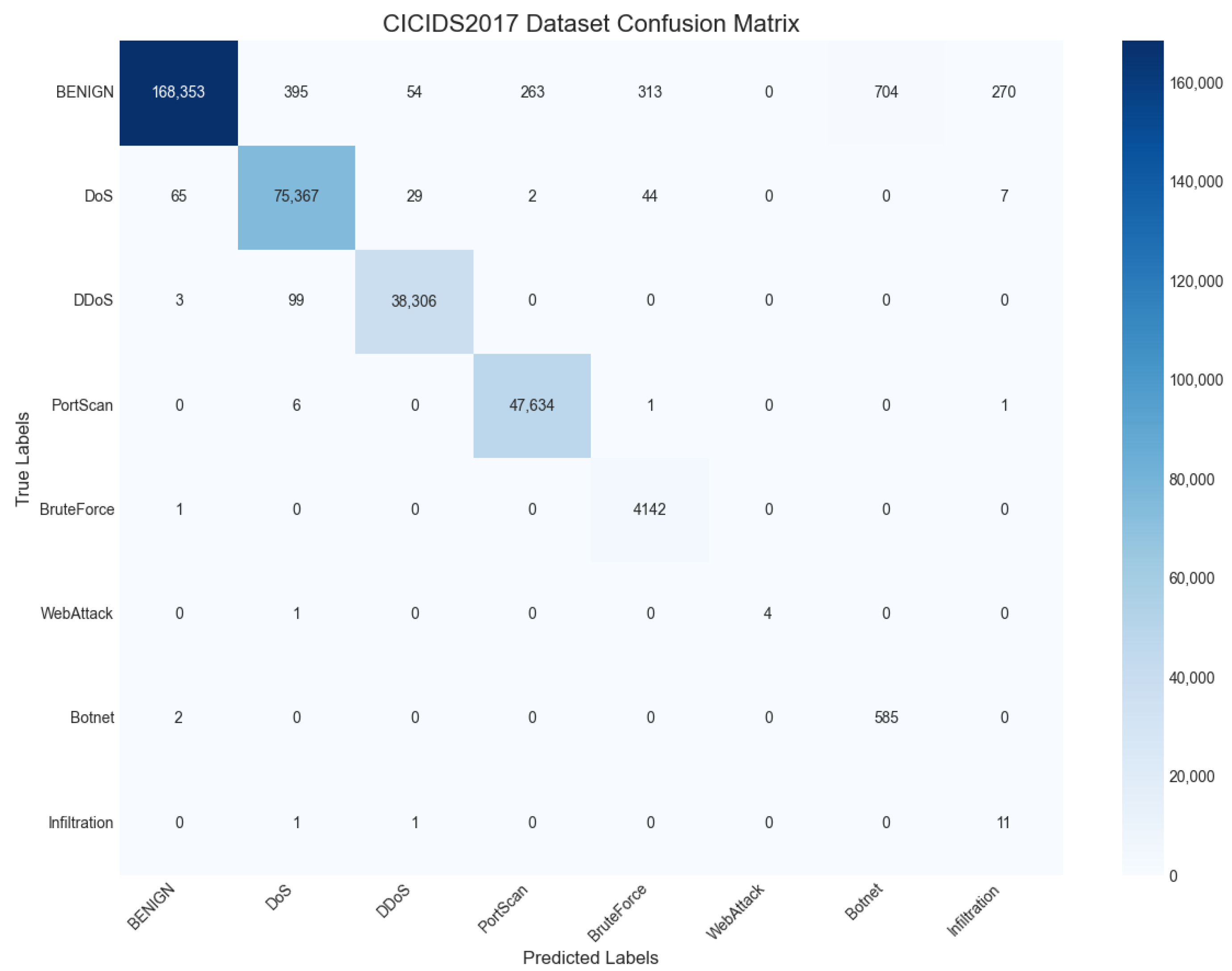

This research first used the CICIDS2017 dataset to verify the proposed ResCAE-BiGRU model.

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the accuracy of this model on the training set and the verification set of the dataset with the number of training rounds.

Figure 6 shows the confusion matrix of the model’s performance on the CICIDS2017 dataset. It should be noted that for the purpose of clear visualization, several attack sub-categories listed in

Table 2 have been aggregated into their parent categories. For example, attacks such as “FTP-Patator” and “SSH-Patator” are represented under the single “BruteForce” label. Furthermore, attack classes with extremely few samples, like “Heartbleed” and “Web Attack-SQL Injection”, have been omitted from the matrix to maintain readability. It can be seen that even if you only train for 50 rounds, the performance on the verification set is still considerable.

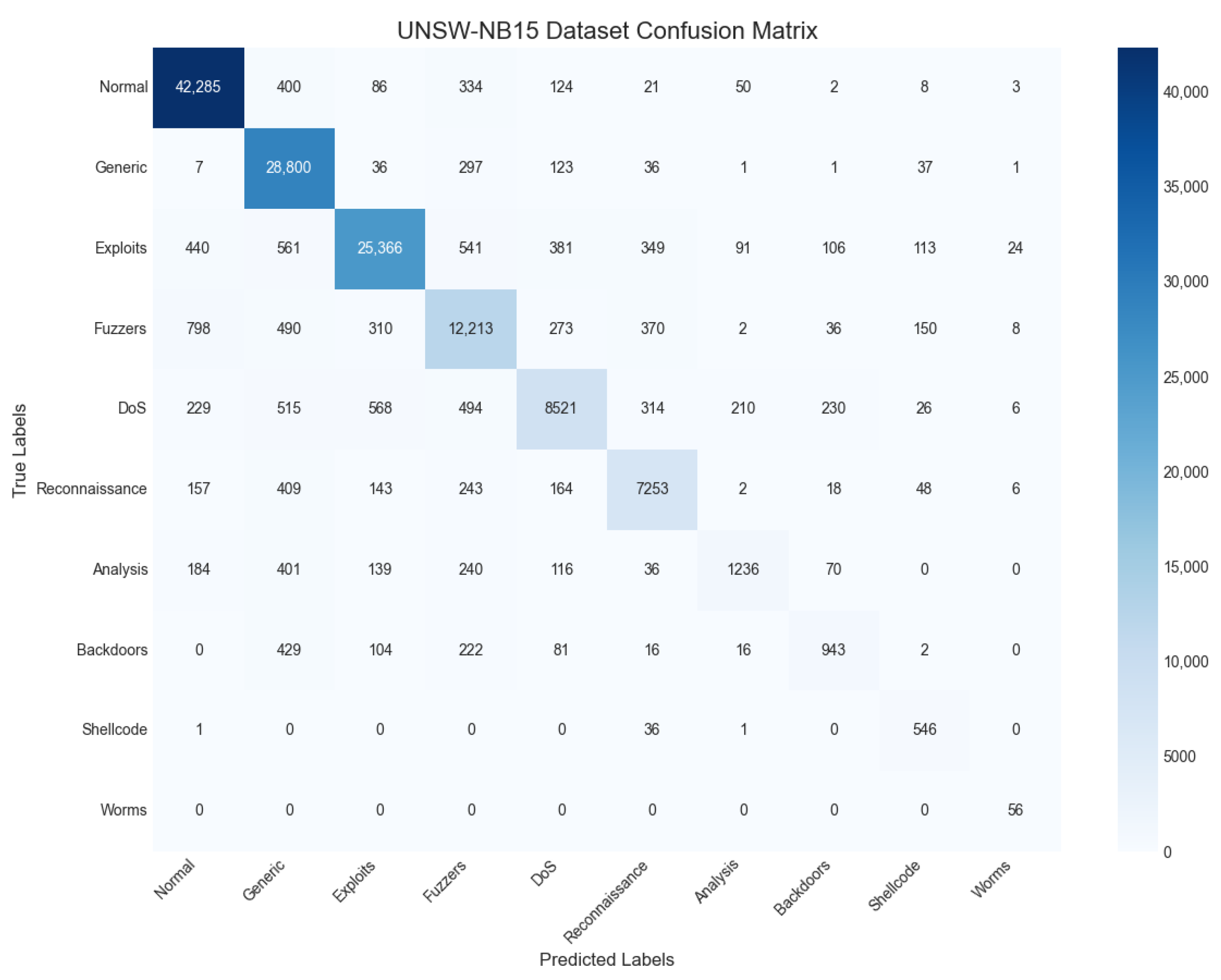

Figure 7 illustrates the training and validation performance of the ResCAE-BiGRU model on the UNSW-NB15 dataset over 50 epochs. The figure contains two plots: one depicting the model’s accuracy and the other showing its loss. In both plots, the

x-axis represents the training epoch, and the

y-axis represents the metric value (accuracy or loss).

The model exhibited strong convergence and generalization capabilities during the training process. As shown in the loss curves, the training and validation losses both decreased rapidly in tandem from the initial epoch, eventually stabilizing at a low value of approximately 0.44 after about 30 epochs. The two loss curves remain in close proximity throughout training, and the small gap between them indicates that the model effectively avoided overfitting. A similar trend is observed in the accuracy curves, where the training and validation accuracies rose concurrently, increasing from an initial 70% to a stable peak of approximately 91%. Despite slight fluctuations in the validation accuracy, its overall trend remained highly consistent with the training accuracy, suggesting a robust training process.

Collectively, the concurrent decrease in loss and increase in accuracy across both the training and validation sets demonstrate that the model was trained effectively, reached a stable state of convergence, and possesses strong generalization performance. The model’s classification performance on the dataset is further detailed by the confusion matrix in

Figure 8.

Table 5 presents the per-class accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores on the CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15 datasets, demonstrating the proposed model’s high efficacy and generalization capabilities.

While the proposed model demonstrates exceptional overall performance across most categories, it is important to analyze its limitations. As shown in

Table 5, the model’s performance on the “Infiltration” attack class is notably poor, with an F1-score of only 0.073. This can be directly attributed to the extreme rarity of this attack in the dataset, which contains only 34 samples for this category. Even with the application of the SMOTE-Tomek technique, which is designed to address class imbalance, such a small number of initial samples makes it difficult to generate a sufficiently diverse and representative set of synthetic data. Consequently, the model struggles to learn the distinguishing features of this attack class, highlighting a challenge for oversampling-based methods when faced with extremely scarce data. Acknowledging this limitation provides a direction for future work, which could explore few-shot learning techniques for such rare attack types.

4.2. Ablation Experiment

To evaluate the contribution of iForest [

31] and the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) optimizer [

27], an ablation study was conducted on the CICIDS2017 dataset. The results are presented in

Table 6.

The baseline ResCAE + BiGRU model achieved an accuracy of 97.42% and an F1-score of 97.29%. This performance is attributed to ResCAE’s ability to extract spatial features from traffic data while mitigating gradient explosion, and BiGRU’s capacity to capture long-range dependencies and prevent information loss during learning. Integrating SAM (ResCAE + BiGRU + SAM) improved the accuracy and F1-score to 98.39% and 98.35%, respectively. This improvement is because SAM enhances model generalization by guiding convergence towards flatter loss minima rather than sharp ones.

Incorporating iForest for outlier removal (iForest + ResCAE + BiGRU) yielded an accuracy of 98.55% and an F1-score of 98.30%. This is because pre-processing with iForest clarifies the decision boundary between normal and attack classes, which mitigates class overlap and prevents the subsequent oversampling step from generating noisy, borderline synthetic samples. When applying SMOTE (SMOTE + ResCAE + BiGRU), the accuracy and F1-score rose to 99.03% and 98.94%, respectively, by addressing the inherent class imbalance and allowing the model to learn more effectively from minority attack classes.

Finally, the full proposed model, which combines all components, achieved the highest performance, with an accuracy of 99.33% and an F1-score of 99.41%. These results confirm that each component contributes positively to the model’s overall efficacy in detecting attack classes.

4.3. Comparison Experiment

To evaluate the detection effectiveness of the proposed model, its performance was benchmarked on the CICIDS2017 dataset. For this experiment, a subset of the data was created by combining the normal traffic (from Monday) with all available attack traffic. This dataset was then partitioned into a 70% training set and a 30% testing set. The proposed model’s performance was then compared against several baseline models: DT [

1], CNN-LSTM [

35], AE-ResNet [

13], and LCVAE-CBiLSTM [

5]. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 7 and

Figure 9. As shown, the proposed model achieved an accuracy of 99.33%, a precision of 99.53%, a recall of 99.33%, and an F1-score of 99.41%.

When compared to the traditional machine learning model (DT), the proposed model demonstrates superior performance across all four metrics, including an accuracy improvement of over one percentage point. This suggests that for complex network traffic data, deep learning architectures can learn more effective feature representations than shallow models. Traditional methods like Decision Trees often rely on manual feature engineering and have a limited capacity to capture the intricate patterns inherent in such data.

The performance gap is particularly evident when compared to the standard CNN-LSTM model, which our model outperforms by a significant margin: the proposed model achieves an F1-score of 99.41%, whereas the CNN-LSTM scores only 81.36%. CNN-LSTM’s recall is particularly low at 76.83%, indicating a failure to detect a substantial number of attacks. This highlights that the proposed model’s architecture, incorporating a residual autoencoder (ResCAE) and advanced optimization (SAM), provides substantially improved feature extraction and generalization capabilities compared to a standard CNN-LSTM.

In comparison to AE-ResNet, our model shows a notable advantage in both accuracy and recall, suggesting a more comprehensive identification of attack samples. Although AE-ResNet achieves slightly higher precision and F1-scores, our model excels in recall while maintaining competitively high precision, indicating a better balance in detecting true positives. The proposed model also surpasses LCVAE-CBiLSTM in overall accuracy, precision, and F1-score. Although LCVAE-CBiLSTM achieves the highest recall, this comes at the cost of lower precision, resulting in a less balanced overall performance, as reflected by its lower F1-score compared to our model.

Overall, the superior performance of the proposed framework is not due to a single component, but rather the synergistic combination of its architecture and training strategy, which directly address the core challenges of imbalanced traffic detection. First, the architectural design provides superior feature extraction. Unlike DT, which uses traditional machine learning, our ResCAE-BiGRU learns deeper, non-linear features. Compared to AE-ResNet, while it uses a ResNet, its architecture lacks a crucial temporal analysis component. Our framework explicitly includes a BiGRU layer to capture the critical contextual and sequential dependencies inherent in network attacks, which AE-ResNet overlooks. Second, our optimization strategy is far more focused on imbalance and generalization. The CNN-LSTM model low F1-score (81.36%) is likely due to its use of standard binary cross-entropy, which is heavily biased towards the majority class on imbalanced data. Our model, in contrast, employs Focal Loss, forcing it to prioritize hard-to-classify minority attacks. Furthermore, our model utilizes the SAM optimizer, which significantly boosts generalization by finding flat loss minima, an advanced technique not adopted in any of the compared papers. This comprehensive approach, combining iForest cleaning, ResCAE deep features, BiGRU temporal analysis, Focal Loss for imbalance, and SAM for generalization, explains why our model achieves the best overall performance in building a robust and balanced classifier.

5. Conclusions

To address the challenge of low anomaly detection rates caused by class imbalance in network traffic, particularly for minority anomaly classes, this paper proposes a deep learning framework for anomaly detection in imbalanced network traffic, ResCAE-BiGRU.

The proposed methodology begins with a two-stage data optimization process. First, outliers are removed using the Isolation Forest (iForest) algorithm to enhance data quality. Subsequently, the SMOTE-Tomek technique is applied to oversample minority anomaly classes, thereby mitigating the class imbalance problem. The model training phase employs a two-stage strategy. Initially, the ResCAE module is pre-trained in an unsupervised manner, enabling its encoder to learn robust, generalized feature representations from the traffic data. In the supervised fine-tuning stage, the pre-trained ResCAE encoder is integrated with a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) network to capture bidirectional temporal dependencies within the data features. Furthermore, the Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) optimizer, utilizing an SGD base, is employed to guide the model towards flatter loss minima, which enhances its generalization capabilities.

Comprehensive experimental results on the CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15 datasets demonstrate the excellent performance of the proposed model. A comparative analysis confirms that the ResCAE-BiGRU model not only surpasses traditional machine learning algorithms but is also highly competitive with, and in some aspects superior to, other contemporary deep learning models. The results demonstrate that this method effectively addresses the challenge of class imbalance, significantly improving the overall performance of anomaly detection in network traffic. This work provides a robust foundation for developing more effective network traffic anomaly detection frameworks. Future work will focus on validating the model’s effectiveness and generalizability across a broader range of datasets.