Symmetric Folding: An Efficient Method for Accelerating Witness-Based Random Search

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Terminologies, Notations, and Definitions

2.1. Terminologies and Notations

2.2. Definitions

3. Theoretical Results

4. Applications for Folding and Searching Rectangular Datasets

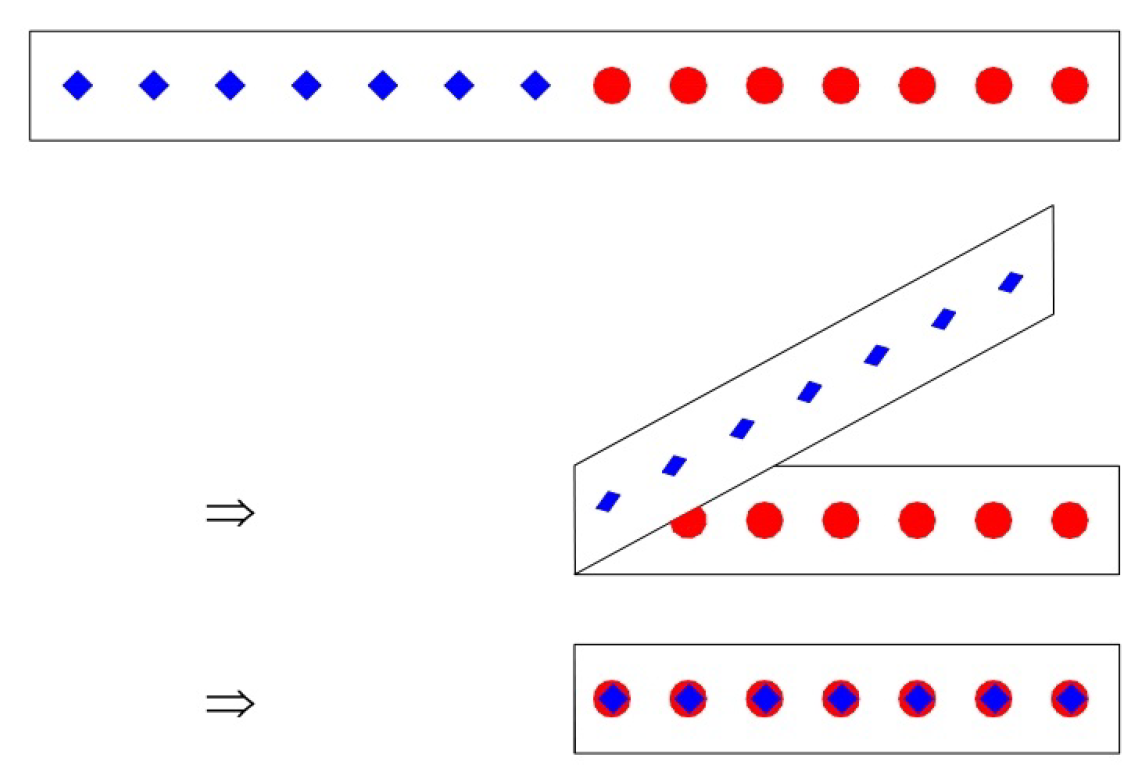

4.1. Folding and Searching Dataset

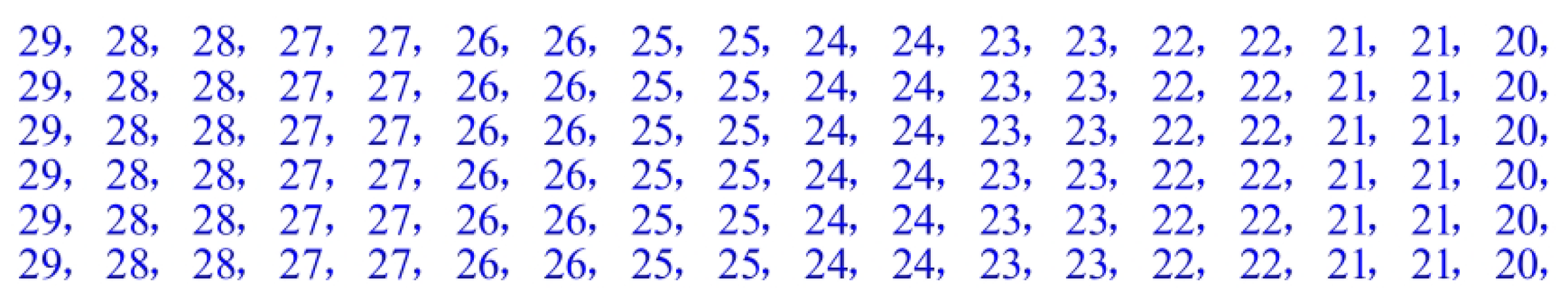

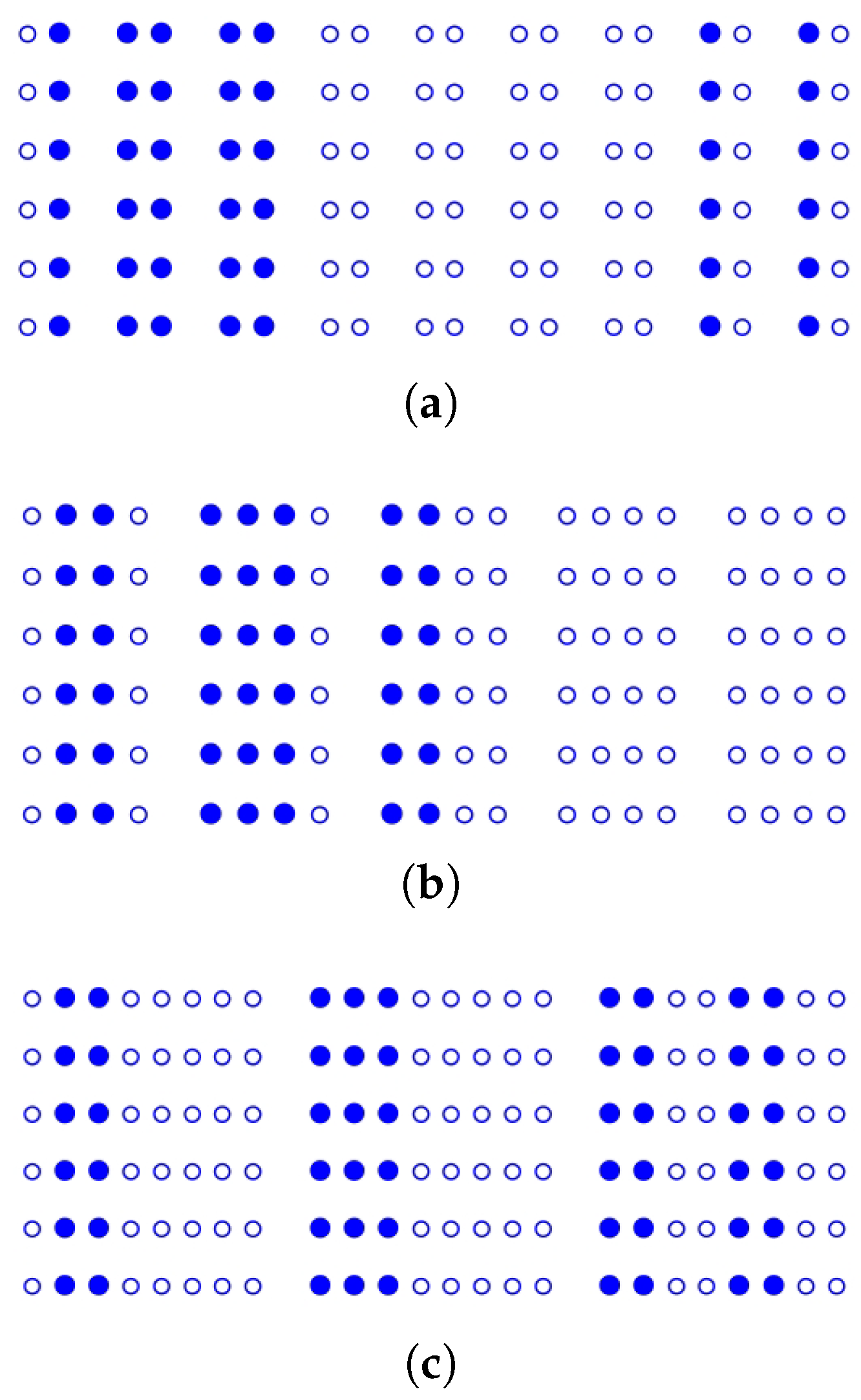

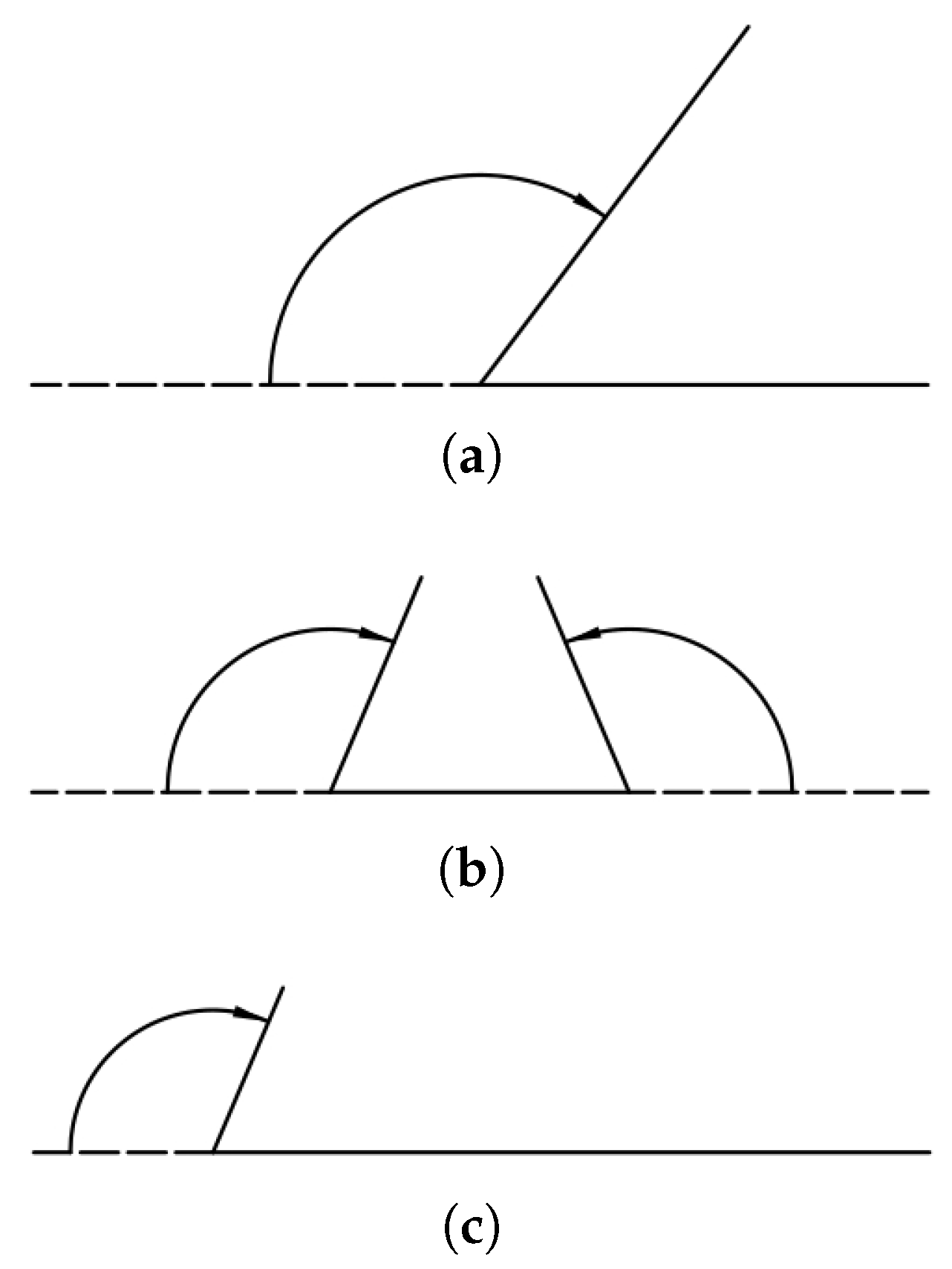

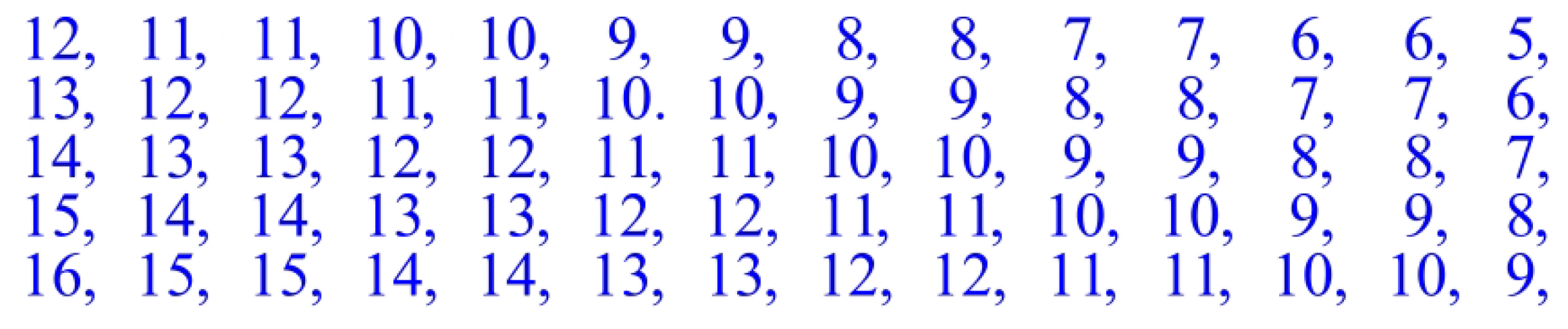

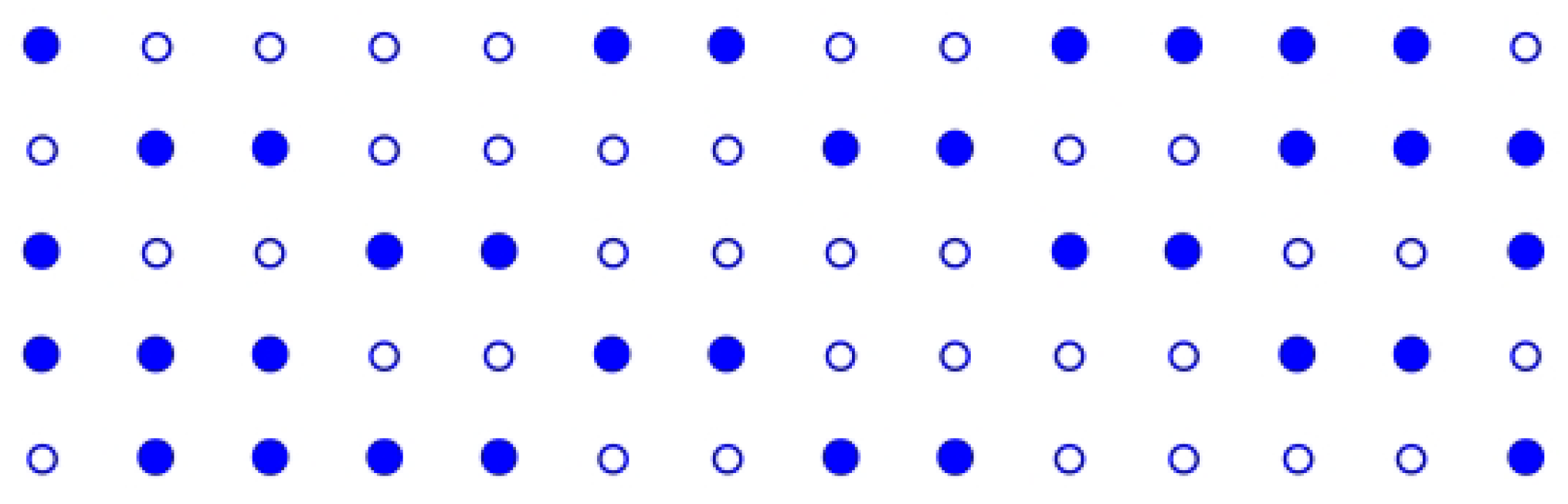

4.1.1. Structure and Folding Characteristics of

4.1.2. A Strategy for Folding and Searching

4.1.3. An Approach for Folding and Searching

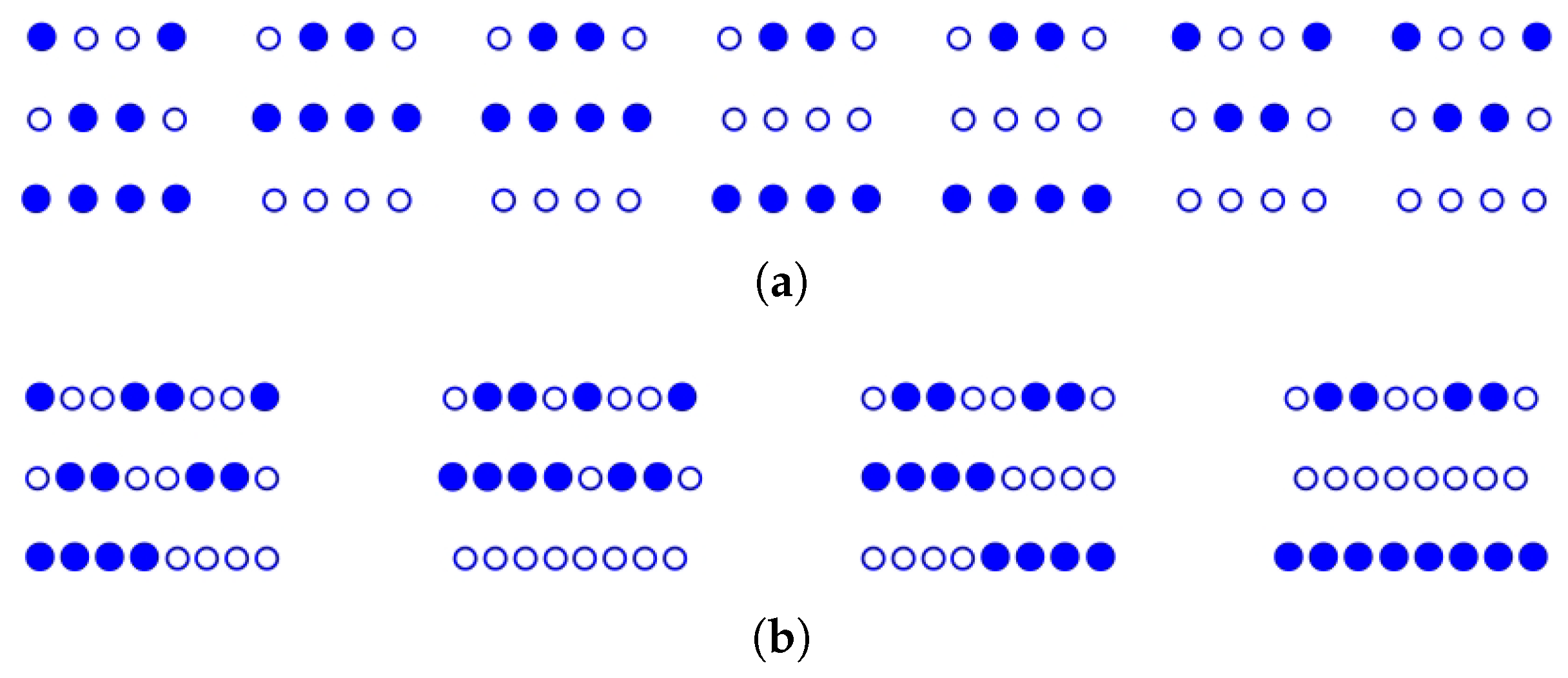

4.2. Folding and Searching Dataset

4.2.1. Structure and Folding Characteristics of

4.2.2. A Strategy for Folding and Searching

- (1)

- Conduct an h-fold of the last row onto the first row to obtain a folded strip S.

- (2)

- Fold and search S with the same approach as folding and searching a strip of .

4.2.3. An Approach Folding and Searching

4.3. Superimposing on and Searching It

4.4. Numerical Experiments

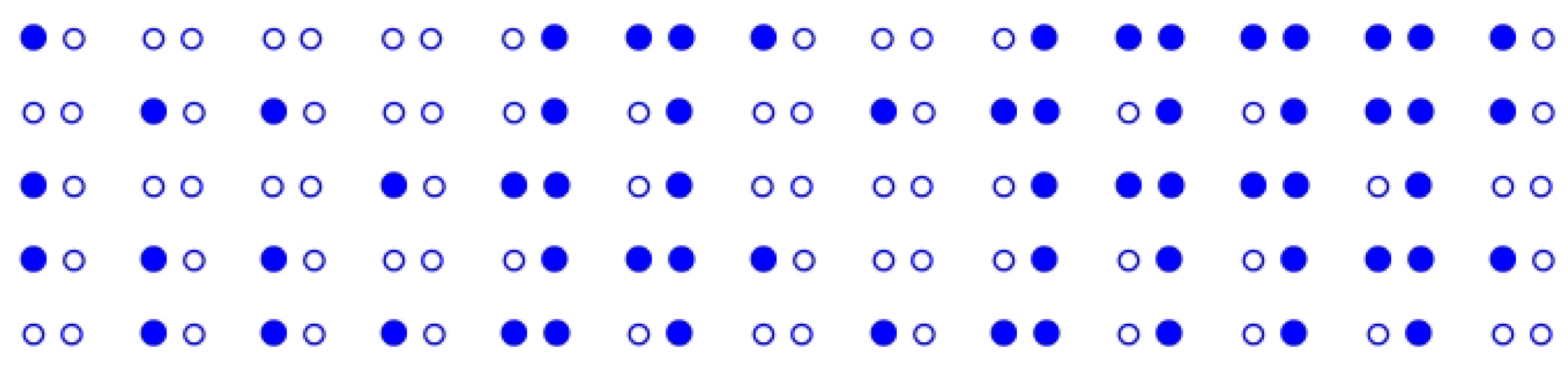

4.5. More Application Scenarios

- Blind search issue. A blind search searches for objectives within a restricted area without previously assigning information about them. A concrete example of such a search is fault diagnosis in industry, such as detecting the fault spot within a material through data analysis, identifying the faulty component in a large-scale integrated circuit, and so on. Those detections are always performed with an embedded diagnosis system. By structuring the source data, folding can improve the computational efficiency of the system.

- Database issue. A database is a structured repository for storing and frequently accessing large volumes of data. Each database can be conceptualized as a sheet composed of rows and columns. According to Remarks 4 and 6, applying k iterations of symmetric folding results in a single cell in the folded sheet corresponding to distinct cells in the original database. As a result, querying a single cell in the folded sheet provides simultaneous access to cells in the original database, thereby significantly improving search efficiency.

- Engineering optimization issue. Engineering optimization constantly searches for a solution in a large computational domain. Partitioning the domain first and then folding the partitioned result, as we do with and , can lead to multiple subdomains being synchronically searched, thus enhancing computational efficiency.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Littman, M.L. The Witness Algorithm: Solving Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes; Technical report; Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Poupart, P. Exploiting Structure to Efficiently Solve Large-Scale Partially Observable Decision Processes. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alon, N.; Naor, M. Derandomization, witnesses for Boolean matrix multiplication and construction of perfect hash functions. Algorithmica 1996, 16, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Deng, J.; Han, Y.S.; Varshney, P.K. A witness-based approach for data fusion assurance in wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 1–5 December 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederix, D. Starting in the Middle: Witness-Based Itemset Mining. Master’s Thesis, Kargolieke University, Leuven, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chini, P.; Massoud, R.; Meyer, R.; Saivasan, P. Fast Witness Counting. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.05777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saan, S. Witness Generation for Data-Flow Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.D.; Leyva-Mayorga, I.; Popovski, P. Witness-based Approach for Scaling Distributed Ledgers to Massive IoT Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 6th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–16 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, J.R.; Wu, Y. Witness-Based Searchable Encryption with Aggregative Trapdoor. In Security with Intelligent Computing and Big-Data Services (SICBS 2018); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaziova, P.; Beyer, D.; Lingsch-Rosenfeld, M.; Spiessl, M.; Strejcek, J. Software Verification Witnesses 2.0. In Model Checking Software; Neele, T., Wijs, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Huang, X.; Fei, S. Witness based nonlinear detection of quantum entanglement. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.02868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, M.K. An introduction to randomized algorithms. Discret. Appl. Math. 1991, 34, 165–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, R.; Raghavan, P. Randomized algorithms. ACM Comput. Surv. 1995, 28, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromkovič, J. Algorithmic Adventures: From Knowledge to Magic; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; p. 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, T.K. The Art of Randomness: Randomized Algorithms in the Real World; No Starch Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; p. 638. [Google Scholar]

- Aspnes, J. Notes on Randomized Algorithms. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2003.01902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromkovič, J. Design and Analysis of Randomized Algorithms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; p. 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Garg, D. Randomized Algorithms: Methods and Techniques. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2011, 28, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X. A Property of Point Symmetry Under Symmetric Folding Transformation. Asian Res. J. Math. 2025, 21, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. A Dataset and A Dynamic Distributed Parallel Network for Identifying Divisors of Odd Composite Integers. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2025, 40, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, X. A Novel Dataset and Algorithm for Identifying Divisors of an Odd Composite Integer Using Distributed Parallel Network. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2025, 40, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Math Forum Drexel University and Jessica Wolk-Stanley. In Dr. Math Introduces Geometry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; p. 137.

- Umble, R.N.; Han, Z. Transformational Plane Geometry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- MathBitsNotebook Symmetry in Geometry; Mathbitsnotebook: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- Graham, R.L.; Knuth, E.E.; Patashnik, O. Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 67–101. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X. A Boundary Property of Dataset ΠC. Int. J. Math. Trends Technol. 2025, 71, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadee, A.M.; Kamrujjaman, M. Cryptanalysis of RSA Cryptosystem: Prime Factorization using Genetic Algorithm. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.05944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Integer N | Digits | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10,909,343 | 8 | 3.54 | 2.66 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| 29,835,457 | 8 | 2.63 | 1.97 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| 392,913,607 | 9 | 3.59 | 2.69 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| 5,325,280,633 | 10 | 2.37 | 1.78 | 0..32 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| 42,336,478,013 | 11 | 2.38 | 1.79 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| 272,903,119,607 | 12 | 2.12 | 1.59 | 1.05 | 0.27 | 0.20 |

| 11,683,458,677,563 | 14 | 5.15 | 3.86 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| 51,790,308,404,911 | 14 | 3.73 | 2.80 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.34 |

| 115,137,038,087,959 | 15 | 3.65 | 2.74 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.45 |

| 8,335,465,900,089,539 | 16 | 3.30 | 2.48 | 15.66 | 1.64 | 1.23 |

| 10,380,088,039,872,631 | 17 | 13.04 | 9.78 | 8.57 | 2.23 | 1.67 |

| 253,422,413,591,685,001 | 18 | 31.66 | 23.75 | 8.60 | 1.29 | 0.97 |

| 1,160,633,764,479,964,633 | 19 | 52.60 | 39.45 | 9.72 | 1.45 | 1.09 |

| 31,625,125,947,164,338,313 | 20 | 192.09 | 144.07 | 10.25 | 1.91 | 1.43 |

| 454,367,322,351,811,534,933 | 21 | 329.11 | 246.83 | 22.55 | 4.12 | 4.09 |

| 4,500,000,514,520,012,390,279 | 22 | 1875.85 | 1406.89 | 45.95 | 15.83 | 13.87 |

| 26,785,956,134,870,280,125,273 | 23 | 10,118.36 | 7588.77 | 168.75 | 76.05 | 67.04 |

| Integer N | Digits | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12,654,529 | 8 | 3.02 | 2.27 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.26 |

| 369,717,133 | 9 | 2.87 | 2.15 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.27 |

| 1,897,440,553 | 10 | 2.57 | 1.93 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.26 |

| 52,739,663,177 | 11 | 6.00 | 4.50 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.26 |

| 130,713,369,233 | 12 | 2.14 | 1.61 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.27 |

| 6,748,770,789,473 | 13 | 3.37 | 2.53 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.28 |

| 11,524,840,919,477 | 14 | 2.58 | 1.94 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.28 |

| 430,485,039,573,419 | 15 | 5.23 | 3.92 | 1.53 | 1.14 | 0.86 |

| 1,955,733,632,904,137 | 16 | 6.43 | 4.82 | 4.84 | 4.68 | 3.51 |

| 30,217,484,037,846,601 | 17 | 5.79 | 4.34 | 8.41 | 3.23 | 2.42 |

| 266,941,704,466,880,371 | 18 | 4.87 | 3.65 | 8.96 | 3.25 | 2.44 |

| 2,166,633,888,615,295,159 | 19 | 31.86 | 23.90 | 9.95 | 3.56 | 2.67 |

| 22,756,653,803,671,245,041 | 20 | 97.06 | 72.80 | 21.29 | 3.80 | 2.85 |

| 413,222,670,126,548,323,081 | 21 | 397.38 | 298.04 | 22.31 | 11.75 | 8.81 |

| 1,503,913,043,740,073,215,127 | 22 | 861.5 | 646.13 | 33.95 | 18.95 | 14.22 |

| 23,208,481,761,499,119,809,917 | 23 | 3054.51 | 2290.88 | 92.26 | 64.89 | 48.67 |

| Integer N | Digits | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11,157,067 | 8 | 2.21 | 1.66 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.29 |

| 383,910,353 | 9 | 3.37 | 2.53 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.24 |

| 1,438,236,853 | 10 | 2.54 | 1.91 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| 59,495,473,109 | 11 | 2.37 | 1.78 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| 204,338,073,419 | 12 | 1.75 | 1.31 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| 4,075,254,216,277 | 13 | 3.17 | 2.38 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.36 |

| 16,522,992,841,517 | 14 | 2.33 | 1.75 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.39 |

| 415,613,171,542,577 | 15 | 3.40 | 2.55 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.22 |

| 2,130,887,677,054,559 | 16 | 19.12 | 14.34 | 5.07 | 1.05 | 1.07 |

| 31,043,832,317,143,097 | 17 | 7.65 | 5.74 | 8.80 | 1.21 | 1.80 |

| 209,495,243,841,913,543 | 18 | 14.38 | 10.79 | 7.99 | 1.25 | 1.99 |

| 4,082,205,679,196,499,709 | 19 | 6.14 | 4.61 | 9.34 | 1.68 | 2.34 |

| 33,019,716,065,589,397,447 | 20 | 597.08 | 447.81 | 32.28 | 2.77 | 2.28 |

| 450,574,758,051,764,161,729 | 21 | 397.38 | 298.04 | 43.81 | 1.71 | 3.81 |

| 1,878,613,353,066,239,152,189 | 22 | 2069.93 | 1552.45 | 46.03 | 19.71 | 16.03 |

| 27,913,133,719,399,938,961,837 | 23 | 7894.19 | 5920.64 | 48.06 | 12.60 | 48.06 |

| Integer N | Digits | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13,414,967 | 8 | 2.96 | 2.22 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.36 |

| 331,451,893 | 9 | 2.76 | 2.07 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| 1,933,146,287 | 10 | 3.28 | 2.46 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.34 |

| 61,376,888,039 | 11 | 4.50 | 3.38 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| 221,449,201,327 | 12 | 2.93 | 2.20 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.99 |

| 8,356,391,888,797 | 13 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| 10,503,658,570,897 | 14 | 3.89 | 2.92 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| 530,802,693,107,327 | 15 | 3.66 | 2.75 | 3.03 | 1.53 | 1.03 |

| 1,571,847,149,341,363 | 16 | 5.63 | 4.22 | 3.59 | 1.04 | 1.59 |

| 30,266,236,030,889,197 | 17 | 7.30 | 5.48 | 9.19 | 1.09 | 1.19 |

| 227,020,160,422,765,063 | 18 | 28.62 | 21.47 | 8.67 | 2.16 | 1.67 |

| 7,632,766,872,780,422,213 | 19 | 21.16 | 15.87 | 7.601 | 2.36 | 1.60 |

| 28,518,585,380,150,198,561 | 20 | 171.77 | 128.83 | 10.62 | 1.91 | 2.62 |

| 549,438,783,354,451,709,261 | 21 | 809.52 | 607.14 | 22.11 | 2.55 | 12.11 |

| 1,885,102,352,659,402,618,003 | 22 | 1827.62 | 1370.72 | 79.39 | 3.79 | 39.39 |

| 21,852,468,492,088,577,490,449 | 23 | 5153.08 | 3864.81 | 90.91 | 58.10 | 90.91 |

| Integer N | Digits | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11,427,677 | 8 | 1.81 | 1.36 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.26 |

| 405,031,259 | 9 | 1.34 | 1.01 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| 1,354,177,351 | 10 | 2.03 | 1.52 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| 61,111,357,501 | 11 | 2.14 | 1.61 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| 190,838,622,707 | 12 | 1.88 | 1.41 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.29 |

| 3,856,534,651,811 | 13 | 2.98 | 2.24 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.26 |

| 15,286,768,369,531 | 14 | 1.41 | 1.06 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| 450,109,181,452,867 | 15 | 6.94 | 5.21 | 1.20 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| 1,317,487,523,002,697 | 16 | 2.46 | 1.85 | 3.27 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| 31,042,285,010,899,441 | 17 | 4.01 | 3.01 | 15.25 | 1.04 | 0.78 |

| 218,532,124,445,731,211 | 18 | 3.53 | 2.65 | 8.63 | 1.53 | 1.15 |

| 8,202,929,148,558,584,683 | 19 | 111.63 | 83.72 | 8.52 | 2.56 | 1.92 |

| 24,120,674,285,926,579,159 | 20 | 218.28 | 163.71 | 20.42 | 1.56 | 1.17 |

| 464,395,777,895,275,578,169 | 21 | 715.56 | 536.67 | 38.71 | 3.47 | 2.60 |

| 1,789,550,188,834,786,401,307 | 22 | 6229.76 | 4672.32 | 46.03 | 29.6 | 30.2 |

| 29,891,632,748,859,892,878,863 | 23 | 30,481.30 | 22,860.98 | 70.19 | 21.53 | 18.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X. Symmetric Folding: An Efficient Method for Accelerating Witness-Based Random Search. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122086

Wang X. Symmetric Folding: An Efficient Method for Accelerating Witness-Based Random Search. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122086

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xingbo. 2025. "Symmetric Folding: An Efficient Method for Accelerating Witness-Based Random Search" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122086

APA StyleWang, X. (2025). Symmetric Folding: An Efficient Method for Accelerating Witness-Based Random Search. Symmetry, 17(12), 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122086