Learning Student Knowledge States from Multi-View Question–Skill Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

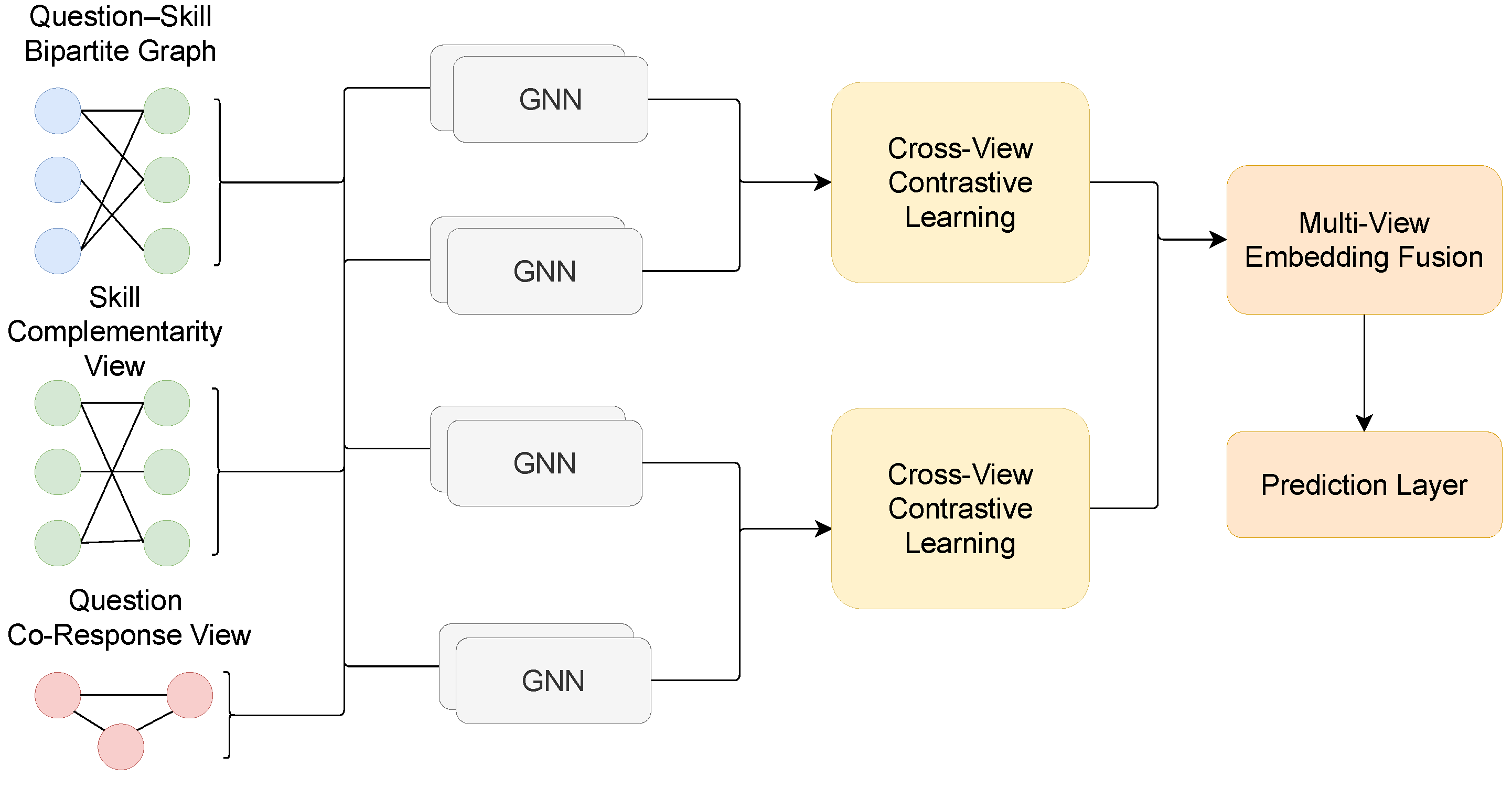

- We introduce three novel relational views for knowledge tracing: a question–skill bipartite graph, a skill complementarity view capturing synergistic skill relationships, and a question co-response view modeling latent question associations from aggregated student answer patterns.

- We design a cross-view contrastive learning module and an attention-guided fusion mechanism to produce unified and expressive knowledge embeddings.

- Extensive experiments on three publicly available datasets demonstrate the superior predictive performance of MVQSN compared to state-of-the-art baselines.

2. Methods

2.1. Problem Definition

2.2. Overview of MVQSN

2.3. Multi-View Construction

2.3.1. Question–Skill Bipartite Graph

2.3.2. Skill Complementarity View

2.3.3. Question Co-Response View

2.4. Cross-View Contrastive Learning

2.5. Student Performance Prediction

3. Experiments

3.1. Datasets

- ASSIST2009 (https://sites.google.com/site/assistmentsdata/home/2009-2010-assistment-data, accessed on 1 May 2025) is a classic K-12 mathematics dataset collected from the ASSISTments online tutoring system. Following standard preprocessing protocols, we exclude entries without skill annotations and remove scaffolding items to ensure data consistency.

- EdNet-KT1 (https://github.com/riiid/ednet, accessed on 1 May 2025) is a large-scale dataset from the Santa learning platform. It contains rich interaction logs between students and questions over multiple sessions. In line with prior work [21], we randomly sample 5000 students for efficient evaluation.

- EdNet-KT2 (https://github.com/riiid/ednet, accessed on 1 May 2025) extends EdNet-KT1 with additional interaction records collected in a later period. We apply identical filtering and sampling strategies to maintain comparability.

3.2. Implementation Details

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

- AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve). Measures the probability that a model ranks a randomly chosen correct response higher than an incorrect one.

- ACC (Accuracy). Reflects the overall proportion of correctly predicted responses.

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error). Quantifies the mean absolute deviation between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes.

- RMSE (Root Mean Square Error). Penalizes large deviations more heavily, capturing the robustness of model predictions.

3.4. Baseline Methods

- Factorization-based: KTM [23], serving as a non-deep baseline incorporating multiple features.

3.5. Overall Performance

3.6. Ablation Study

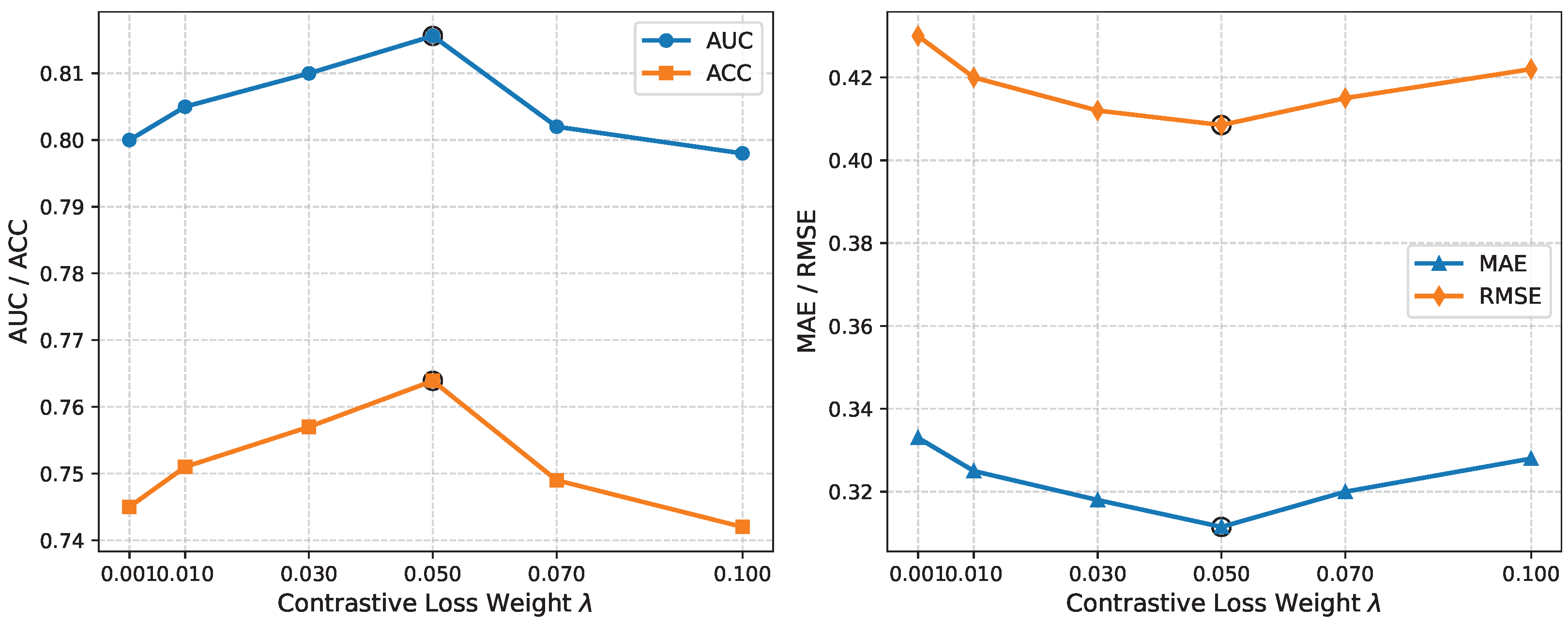

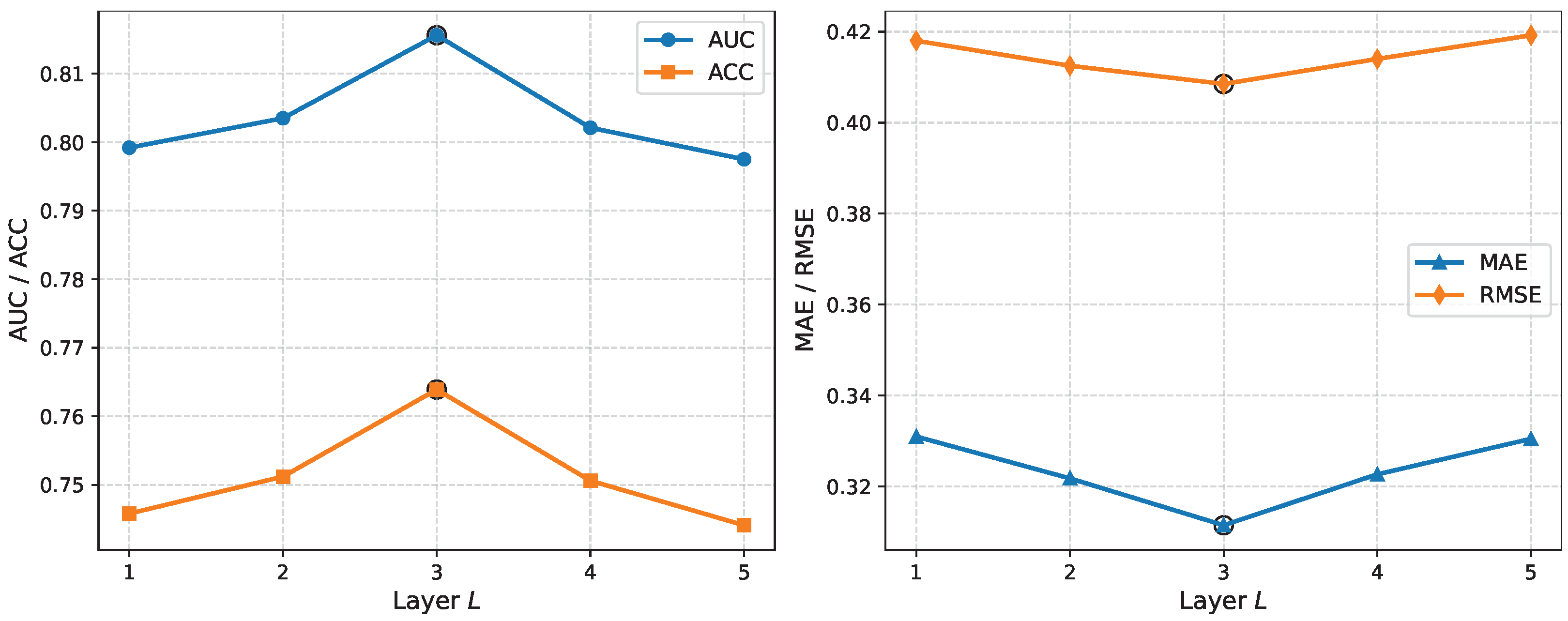

3.7. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

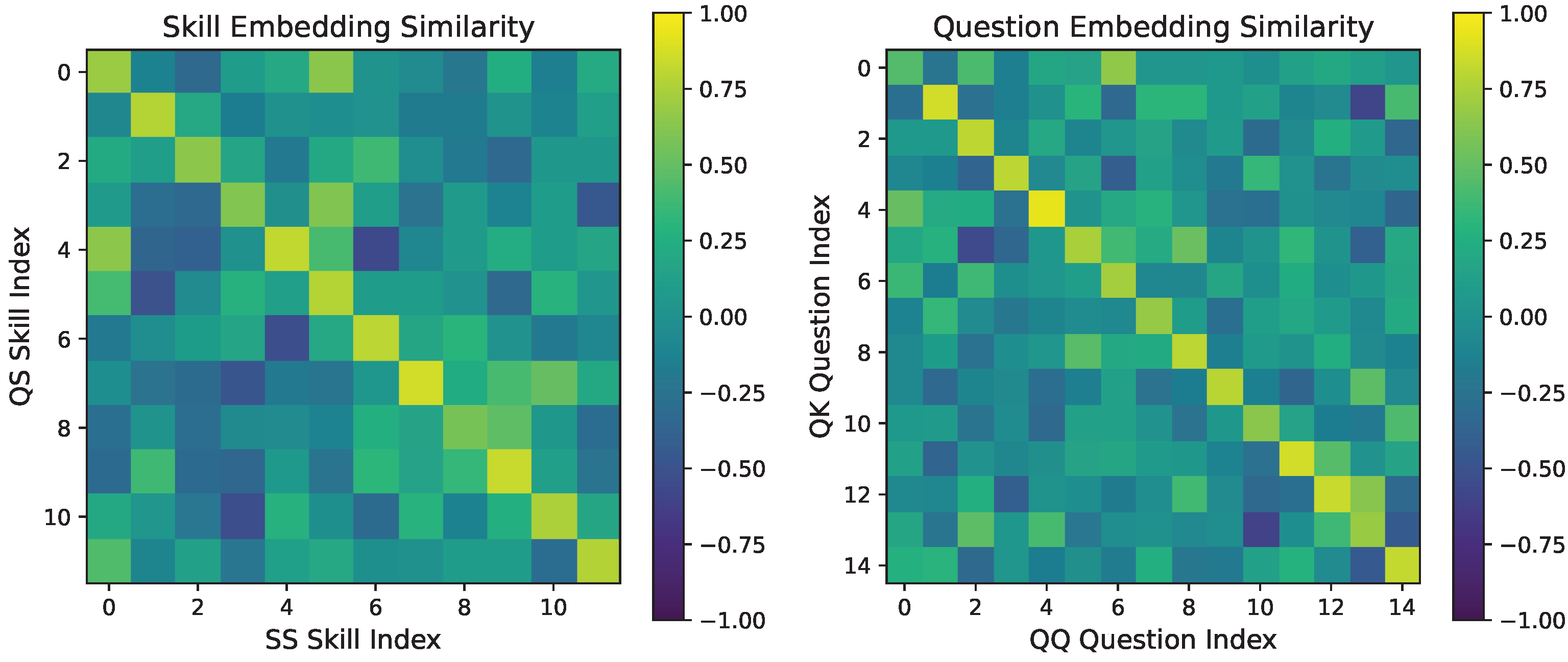

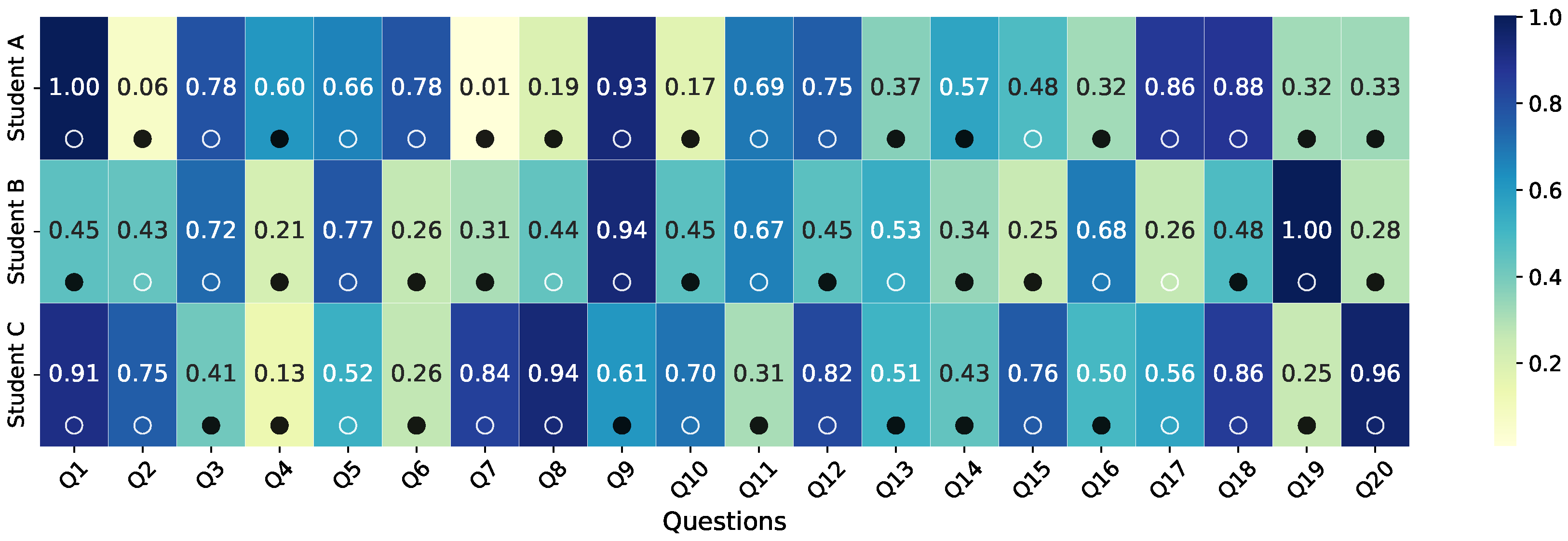

3.8. Case Study Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Mao, S.; Qin, Y.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Y. Hyperbolic Hypergraph Transformer with Knowledge State Disentanglement for Knowledge Tracing. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 4677–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, Y.; Qin, Y.; Mao, S.; Jiang, Y. Dual-Channel Adaptive Scale Hypergraph Encoders with Cross-View Contrastive Learning for Knowledge Tracing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 6752–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, J.; Su, H.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liao, B.; Wu, F. Debiased Cognition Representation Learning for Knowledge Tracing. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Yin, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, E. A Survey of Knowledge Tracing: Models, Variants, and Applications. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1858–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, C.; Bassen, J.; Huang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sahami, M.; Guibas, L.J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. Deep Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Sun, J. Antenna Modeling Based on Image-CNN-LSTM. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propagat. Lett. 2024, 23, 2738–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, J.X. Exploring long- and short-term knowledge state graph representations with adaptive fusion for knowledge tracing. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Karypis, G. A Self Attentive model for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–5 July 2019; pp. 2330–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Heffernan, N.; Lan, A.S. Context-aware attentive knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Virtual Event, CA, USA, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 2330–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M. Deep Attentive Model for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 10192–10199. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, S.; Zhan, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Knowledge Structure-Aware Graph-Attention Networks for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management (KSEM), Singapore, 6–8 August 2022; pp. 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, J.; Qu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y. GIKT: A graph-based interaction model for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Ghent, Belgium, 14–18 September 2020; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P.; Chen, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, D.; Feng, G. CC-GNN: A Clustering Contrastive Learning Network for Graph Semi-Supervised Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 71956–71969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, Y.; Mao, S.; Qin, Y.; Jiang, Y. Knowledge-Associated Embedding for Memory-Aware Knowledge Tracing. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 4016–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, T.; Liang, Q.; Hou, M.; Zhan, B.; Tang, J.; Luo, W.; Weng, J. Deep Learning Based Knowledge Tracing: A Review, a Tool and Empirical Studies. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 4512–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Luo, W. Recent Advances on Deep Learning based Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Singapore, 27 February–3 March 2023; pp. 1295–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Bai, W.; Li, J.; Mao, S.; Jiang, Y. Improving semantic similarity computation via subgraph feature fusion based on semantic awareness. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 136, 108947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, P.; Du, Y.; Jiang, Z. Cross working condition bearing fault diagnosis based on the combination of multimodal network and entropy conditional domain adversarial network. J. Vib. Control 2024, 30, 5375–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ji, A.; Zhou, C.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L. Real-time prediction of TBM penetration rates using a transformer-based ensemble deep learning model. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Gao, P.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X. A fusion framework with multi-scale convolution and triple-branch cascaded transformer for underwater image enhancement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 184, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E.; Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Yin, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, S. Learning Process-consistent Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 1452–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani, K.; Zhang, Q.; Sato, M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, F.; Ohkuma, T. Augmenting knowledge tracing by considering forgetting behavior. In Proceedings of the WWW’19: The Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 3101–3107. [Google Scholar]

- Vie, J.; Kashima, H. Knowledge Tracing Machines: Factorization Machines for Knowledge Tracing. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ma, W.; Zhang, M.; Lv, C.; Wan, F.; Lin, H.; Tang, T.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S. Temporal cross-effects in knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Virtual Event, Israel, 8–12 March 2021; pp. 517–525. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Xia, J.; Jiang, X.; He, T. A novel framework for deep knowledge tracing via gating-controlled forgetting and learning mechanisms. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Qin, J.; Shen, J.; Zhang, W.; Xia, W.; Tang, R.; He, X.; Yu, Y. Improving Knowledge Tracing with Collaborative Information. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Virtual Event, AZ, USA, 21–25 February 2022; pp. 599–607. [Google Scholar]

- Long, T.; Liu, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y. Tracing Knowledge State with Individual Cognition and Acquisition Estimation. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, Canada, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Chen, E.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Yin, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, S. Monitoring Student Progress for Learning Process-Consistent Knowledge Tracing. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 8213–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistics | ASSIST2009 | EdNet-KT1 | EdNet-KT2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of students | 3841 | 5000 | 5000 |

| # of questions | 15,911 | 11,718 | 11,427 |

| # of skills | 123 | 189 | 188 |

| # of records | 258,896 | 498,374 | 394,986 |

| Avg. questions per skill | 156.1 | 136.8 | 133.7 |

| Avg. skills per question | 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Model | Assist2009 | EdNet1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE | AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE | |

| DKT | 0.7484 | 0.7170 | 0.3685 | 0.4366 | 0.6877 | 0.6390 | 0.4440 | 0.4700 |

| DKT-Q | 0.7379 | 0.7107 | 0.3782 | 0.4403 | 0.6913 | 0.6426 | 0.4314 | 0.4691 |

| KTM | 0.7321 | 0.6878 | 0.3904 | 0.4463 | 0.7237 | 0.6716 | 0.4052 | 0.4608 |

| DKTForgetting | 0.7468 | 0.7075 | 0.3746 | 0.4393 | 0.6815 | 0.6349 | 0.4272 | 0.4747 |

| DKTForgetting-Q | 0.7475 | 0.7081 | 0.3708 | 0.4382 | 0.6929 | 0.6455 | 0.4305 | 0.4691 |

| SAKT | 0.6983 | 0.6852 | 0.4078 | 0.4570 | 0.6607 | 0.6210 | 0.4489 | 0.4781 |

| AKT | 0.7210 | 0.6897 | 0.3832 | 0.4568 | 0.7190 | 0.6678 | 0.3971 | 0.4670 |

| GIKT | 0.7948 | 0.7424 | 0.3237 | 0.4254 | 0.7420 | 0.6818 | 0.3980 | 0.4563 |

| HawkesKT | 0.7346 | 0.6942 | 0.3826 | 0.4482 | 0.7166 | 0.6674 | 0.4174 | 0.4642 |

| IEKT | 0.7727 | 0.7260 | 0.3494 | 0.4306 | 0.7319 | 0.6754 | 0.4094 | 0.4566 |

| CoKT | 0.7703 | 0.7223 | 0.3710 | 0.4296 | 0.7244 | 0.6677 | 0.4229 | 0.4584 |

| GFLDKT | 0.7378 | 0.6801 | 0.3809 | 0.4497 | 0.7342 | 0.6743 | 0.4135 | 0.4564 |

| LPKT-S | 0.7832 | 0.7319 | 0.3426 | 0.4339 | 0.7518 | 0.6877 | 0.3695 | 0.4542 |

| KMKT | 0.8129 | 0.7559 | 0.3139 | 0.4117 | 0.7542 | 0.7007 | 0.3542 | 0.4495 |

| MVQSN | 0.3115 | |||||||

| Model | AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKT | 0.6140 | 0.5824 | 0.4746 | 0.4895 |

| DKT-Q | 0.6050 | 0.5703 | 0.4709 | 0.4947 |

| KTM | 0.6509 | 0.6082 | 0.4629 | 0.4834 |

| DKTForgetting | 0.6183 | 0.5864 | 0.4678 | 0.4917 |

| DKTForgetting-Q | 0.6265 | 0.5910 | 0.4652 | 0.4888 |

| SAKT | 0.5677 | 0.5129 | 0.4941 | 0.5000 |

| AKT | 0.6327 | 0.5921 | 0.4613 | 0.4892 |

| GIKT | 0.6512 | 0.6153 | 0.4556 | 0.4868 |

| HawkesKT | 0.6402 | 0.6007 | 0.4685 | 0.4855 |

| IEKT | 0.6530 | 0.6143 | 0.4539 | 0.4902 |

| CoKT | 0.6387 | 0.6042 | 0.4590 | 0.4857 |

| GFLDKT | 0.6556 | 0.6122 | 0.4670 | 0.4815 |

| LPKT-S | 0.6530 | 0.6135 | 0.4583 | 0.4856 |

| KMKT | 0.7035 | 0.6501 | 0.4426 | 0.4773 |

| MVQSN |

| Model | Component | Assist2009 | EdNet1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV | CL | AF | VE | AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE | AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE | |

| w/o • | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7901 | 0.7354 | 0.3367 | 0.4523 | 0.7452 | 0.6895 | 0.3621 | 0.4826 | |

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7983 | 0.7421 | 0.3328 | 0.4478 | 0.7510 | 0.6952 | 0.3589 | 0.4762 | |

| w/o † | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8025 | 0.7468 | 0.3302 | 0.4451 | 0.7543 | 0.6991 | 0.3567 | 0.4728 | |

| w/o ‡ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8010 | 0.7450 | 0.3315 | 0.4463 | 0.7531 | 0.6982 | 0.3572 | 0.4740 | |

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7852 | 0.7308 | 0.3389 | 0.4552 | 0.7420 | 0.6871 | 0.3635 | 0.4853 | ||

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7878 | 0.7325 | 0.3374 | 0.4537 | 0.7438 | 0.6886 | 0.3624 | 0.4837 | ||

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7896 | 0.7343 | 0.3362 | 0.4519 | 0.7461 | 0.6904 | 0.3611 | 0.4818 | ||

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7905 | 0.7358 | 0.3359 | 0.4512 | 0.7468 | 0.6910 | 0.3608 | 0.4812 | ||

| MVQSN (Full) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8156 | 0.7639 | 0.3115 | 0.4085 | 0.7611 | 0.7052 | 0.3496 | 0.4437 |

| Model | MV | CL | AF | VE | AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o • | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6931 | 0.6378 | 0.4512 | 0.4945 | |

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6994 | 0.6429 | 0.4480 | 0.4921 | |

| w/o † | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7008 | 0.6442 | 0.4472 | 0.4913 | |

| w/o ‡ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6997 | 0.6431 | 0.4478 | 0.4919 | |

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6885 | 0.6329 | 0.4551 | 0.4976 | ||

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6908 | 0.6347 | 0.4537 | 0.4963 | ||

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6920 | 0.6361 | 0.4524 | 0.4952 | ||

| w/o | ✓ | ✓ | 0.6925 | 0.6367 | 0.4520 | 0.4949 | ||

| MVQSN (Full) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.7116 | 0.6602 | 0.4340 | 0.4695 |

| View | Assist2009 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QS | SS | AUC | ACC | MAE | RMSE | |

| ✓ | 0.7983 | 0.7421 | 0.3328 | 0.4478 | ||

| ✓ | 0.7755 | 0.7211 | 0.3424 | 0.4635 | ||

| ✓ | 0.7893 | 0.7319 | 0.3376 | 0.4559 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.8022 | 0.7464 | 0.3302 | 0.4439 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.8075 | 0.7514 | 0.3247 | 0.4325 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.7974 | 0.7426 | 0.3319 | 0.4465 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8156 | 0.7639 | 0.3115 | 0.4085 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Xiang, D.; Li, C.; Mao, S.; Chen, Y.; Sun, M.; He, W.; Deng, Y.; Sun, C. Learning Student Knowledge States from Multi-View Question–Skill Networks. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122073

Li J, Xiang D, Li C, Mao S, Chen Y, Sun M, He W, Deng Y, Sun C. Learning Student Knowledge States from Multi-View Question–Skill Networks. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122073

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiawei, Dan Xiang, Chunlin Li, Shun Mao, Yuhuan Chen, Miao Sun, Wei He, Yuanfei Deng, and Chengli Sun. 2025. "Learning Student Knowledge States from Multi-View Question–Skill Networks" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122073

APA StyleLi, J., Xiang, D., Li, C., Mao, S., Chen, Y., Sun, M., He, W., Deng, Y., & Sun, C. (2025). Learning Student Knowledge States from Multi-View Question–Skill Networks. Symmetry, 17(12), 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122073