1. Introduction

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is capable of carrying multi-mission equipment to perform multiple tasks, which is controllable and reusable in most cases. With the rapid development of low-altitude economy and the gradual opening of low-altitude airspace, UAVs are increasingly widely used in logistics and distribution [

1,

2], environmental monitoring [

3,

4], disaster rescue [

5,

6], rural agriculture [

7,

8], engineering design [

9,

10], and other fields. UAV trajectory planning is the premise and key to autonomous, safe, and efficient flight of UAVs, especially in complex three-dimensional environments in a symmetric manner, where multiple constraints such as mountainous terrain, obstacles, no-fly zones, safe altitude, smoothness, flight distance, and so on need to be considered comprehensively and symmetrically in order to realize the optimal path design of UAVs from the starting point to the end point.

Generally, optimal trajectory planning algorithms can be divided into traditional algorithms, evolutionary algorithms, and population intelligent optimization algorithms [

11], while traditional algorithms and evolutionary algorithms are difficult to effectively solve high-dimensional, nonlinear, and large-scale practical problems [

12,

13]. In recent years, the population intelligent optimization algorithm, the new type of heuristic algorithm inspired by the individual and group behaviors of organisms in nature, has been widely used in the field of UAV trajectory planning and numerous research results have been achieved due to its excellent global search capability, powerful adaptability to complex problems, and fast programming implementation [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), as an emerging group intelligence algorithm, achieves a better balance between global and local search by mimicking the foraging and warning behaviors of sparrow groups in nature [

18], but still suffers from the limitations of slow convergence, parameter sensitivity, and it is easy to fall into the local optimization in practical engineering applications. Many scholars at home and abroad have proposed a series of fruitful improvement strategies, such as chaotic perturbation mechanism [

19], Cauchy variation and inverse learning [

20], refractive inverse learning [

21], fusion of Gray Wolf Algorithms for information sharing [

22], dynamic step-size inverse learning [

23], and fusion of ant colony hybrid updating [

24], etc., which provide a new way of thinking for SSA algorithms’ improvement. Recent studies have expanded SSA’s application across diverse path-planning scenarios. For instance, comparative analyses in complex 3D environments such as aircraft surface inspection have been demonstrated SSA’s performance against other algorithms [

25]. To enhance its efficacy, variants like the Composite Chaotic Adaptive SSA (ICCA-SSA) have been developed, which improves global search through chaotic mapping and demonstrates superior performance in mobile robot path planning [

26]. Other notable improvements include the Non-linear Normal Differential SSA (NLN-DSSA) for better global-local balance [

27], and the SSAPO algorithm that integrates dynamic weights and Cauchy mutation to find shorter 3D UAV paths [

28]. Fusing SSA with an Improved Dynamic Window Approach has been proven effective for UAV navigation among dynamic obstacles [

29]. These efforts highlight the versatility and ongoing advancement of SSA in solving complex path-planning problems.

UAV trajectory planning is a complex global optimization problem, which needs to consider many constraints such as mountain terrain, obstacles, no-fly zones, safety altitude, smoothness, flight distance, etc., and it is a typical engineering practice problem to test the improvement of optimization algorithms. The limitations of traditional SSA are addressed and an improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) is proposed. In the new ISSA algorithm, the positive sine–cosine function and the Lévy flight strategy is integrated, and the perturbation to prevent local optimality is maintained while emphasizing more on the dynamic refinement control of the search step size and the cross-region exploration ability, in order to improve the efficiency and robustness of the algorithm, and at the same time effectively solve the UAV trajectory planning problem in complex 3D environments. Simulation results show that the ISSA algorithm outperforms the traditional algorithm in terms of convergence speed, path cost, obstacle avoidance safety and path smoothing, and is able to satisfy the requirement of obtaining higher-quality flight paths within a shorter number of iterations, which provides a new way of thinking for three-dimensional trajectory planning of UAVs in complex environments.

2. Model Establishment

UAV trajectory planning is the precondition and critical element for executing tasks, and the main goal is to provide an optimal or near-optimal flight path from the starting point to the end point for UAVs in complex three-dimensional environments in symmetric style, under the conditions of meeting multiple constraints, such as flight safety, energy consumption limitation, and obstacle avoidance, etc. A fixed-wing logistics UAV, which contains design flight altitude that has an important impact on the load capacity and endurance, is utilized in the simulation process. Thus, the trajectory planning problem is transformed into a multi-constraint optimization model in a three-dimensional environment by constructing an environment model and a comprehensive cost function.

2.1. Environmental Modeling

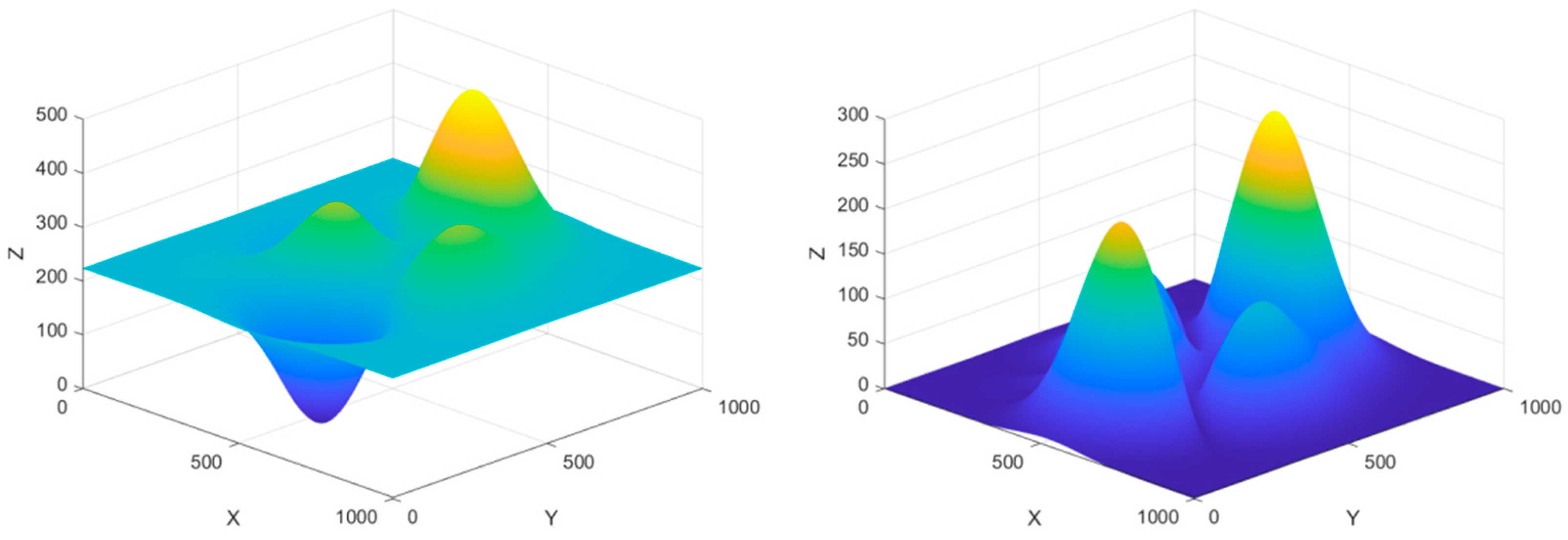

Typical characteristics of real terrain are usually presented as multi-peaks and undulations, such as steep slopes and valleys in mountainous terrain, and high buildings and streets in urban environment. In order to visualize the results and the realism of the simulation environment, the Gaussian function superposition method is utilized to generate adjustable peak height, position, and slope parameters, based on the built-in Peaks function of MATLAB R2024b to generate an initial Gaussian-distributed terrain of a 1000 × 1000 × 500 grid. The mathematical expression is shown in Equation (1), the generated terrain is shown in the left panel of

Figure 1, where the closer color to red stands for the higher elevation value and the closer color to green represents lower the elevation value. Furthermore, the absolute difference between the terrain height and the horizon is calculated using Equation (2) to generate the simulated terrain, as shown in the right panel of

Figure 1.

Herein, Z represents the theoretical height of Gaussian function superposition method, represents the height of the simulated terrain mountain adopted in this paper, represents the height of the horizon, and represents the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the mountain.

In order to simulate the physical constraints and safety requirements in real flight environments, a cylindrical geometric model is adopted to define obstacles and no-fly zones, which can effectively describe the static obstacles and no-fly zones in the complex 3D space by defining the center coordinates, radius, and height parameters.

Suppose

obstacles exist in the environment, then the

-th obstacle are is defined by the following parameters: center coordinates

, which denote the coordinates of the projection of the center of the obstacle to the (X-Y) plane; radius of the obstacle

; and height

. Then, all obstacles can be represented by the following parameter set in Equation (3):

The no-fly zone is also modeled in cylindrical geometry, but differs from obstacles in the presence of height restrictions. Suppose there are

no-fly zones in the environment, and the

-th no-fly zone can be denoted by center coordinates

, radius

, and height range

. The set of no-fly zones (NFZ) can be expressed by the following parameter set in Equation (4):

2.2. Constraints

In order to ensure flight safety, collision detection and avoidance contains obstacles (Equation (5)) and the no-fly zone (Equation (6)), and needs to be performed for all points in the trajectory planning path:

Meanwhile, the peripheral area of the starting point and the end point needs to be set as an obstacle-free safety zone to ensure safely takeoff and landing. The following takeoff and landing constraints need to be satisfied as follows:

In the above Equations (5)–(10), represents any point of the planning path; represents the coordinates of the starting point; represents the coordinates of the end point; represents the parameters of the -th obstacle;The parameters of -th no-fly zone are represented by ; the safety margin is determined by the size of the drone and maneuvering performance.

2.3. Cost Function

When conducting UAV trajectory planning, the influence of different factors needs to be taken into account. The comprehensive cost function is defined as a weighted combination of path length, threat penalty, flight safety altitude, and path smoothness. The objective of the optimization is to minimize this comprehensive cost.

2.3.1. Path Length

In the process of trajectory planning, the minimization of the flight distance is regarded as the core optimization direction, which will directly affect the mission execution efficiency and economy. In order to quantify this objective, the model of three-dimensional spatial flight segment accumulation is adopted. The specific mathematical expression is shown below:

In Equation (11), the number of waypoints in the planning path is denoted by , and the 3D coordinates of the -th waypoint is denoted by .

2.3.2. Threat Penalty

In the framework of flight safety optimization, the threat penalty cost function is defined as the critical mechanism for avoiding the risky area. The UAV’s obstacle avoidance intensity is adjusted based on the spatial relationship between the quantitative trajectory nodes and the threatening areas. The 3D distance between each waypoint and the threat entity is detected in real time, and the response mechanism is established based on the set safety threshold. When the distance between the waypoint and the threat entity is less than the safety radius, a nonlinear growth of the penalty weight is imposed, which is calculated as shown in the following Equation (12):

In Equation (12), denotes the number of waypoints in the planning path, denotes the 3D distance from the -th waypoint to the nearest obstacle, and denotes the safe avoidance distance threshold. When is satisfied, the penalty term grows squarely with decreasing distance to force the path away from the obstacle; while when , the penalty term is set to zero. In this following simulation, is set to 2.

2.3.3. Safe Flight Altitude

Trajectory planning for UAV is governed by its safe flight altitude as a critical factor. A UAV with low altitude is inclined to collide with ground obstacles, while high altitude may increase energy consumption or violate altitude restrictions. In order to balance safety and efficiency, segmented safe flight altitude penalty function is designed to force the path to satisfy the altitude constraints and to be close to the ideal cruising altitude. The mathematical description is shown as Equation (13):

In Equation (13), is the minimum safe altitude, which is determined by the height of ground obstacles and the error tolerance of the altitude measurement sensor; is the maximum flight altitude of the UAV on the line of the regulatory airspace or the UAV; and is the ideal cruise altitude, which is the optimal altitude for balancing the obstacle avoidance and energy consumption, and takes the average of the sum of the minimum safe altitude and the maximum flight altitude, i.e., . It is worth noting that is a linear penalty coefficient and , which indicates the sensitivity of the control to deviations from the ideal altitude; and is a hard constraint that directly excludes illegal solutions. Within the safety range, the closer the waypoints are to , the lower the total cost is, guiding the algorithm to generate paths that balance safety and efficiency.

2.3.4. Path Smoothing

The purpose of path smoothing is to optimize the continuity and stability of the flight trajectory to avoid loss of control of the UAV or surge in energy consumption due to sudden changes in direction. The path smoothness constraints in 3D trajectory planning are composed of two components: horizontal curvature change and vertical height change.

- (1)

Horizontal direction curvature constraint. The horizontal trajectory curvature is limited to ensure smooth steering. Take the horizontal projection of the

-

th waypoint as

, and the vector of the projections of the three neighboring waypoints can be expressed as

, then the geometric discrete curvature based on the three waypoints

is expressed as shown in Equation (14):

In Equation (14), “×” denotes the vector cross product operation and “‖ ‖” denotes the vector module operation. Squaring penalty is applied for the excess, and the horizontal curvature constraint is shown in Equation (15) below:

In Equation (15), denotes the curvature at -th waypoint in the trajectory; denotes the maximum allowable curvature threshold, and is taken herein. The position difference of three neighboring waypoints in the horizontal direction is used to estimate the horizontal curvature of the target planning trajectory at the node , and if it exceeds the maximum permissible value , a penalty is applied to the point to inhibit a sharp turn in the horizontal direction.

- (2)

Vertical motion constraints. Suppress the height mutation and optimize the lift rate energy consumption. The constraint is shown in Equation (16) below:

In Equation (16), denotes the altitude change rate of the -th waypoint; denotes the horizontal projection length of the segment. Penalties are applied to steep climb or dive paths by quantifying the degree of abrupt vertical motion changes through second-order differencing of the height values of the three waypoints.

The horizontal curvature and vertical acceleration penalties are fused to construct a global path smoothness evaluation index, as shown in Equation (17) below:

In Equation (17), represents the curvature weight coefficients, represents the vertical acceleration weight coefficients, and in this paper, we take and . Path smoothness is quantified through differential geometric properties in this objective evaluation, and co-optimization is performed in both horizontal and vertical dimensions, thereby enabling kinematic constraints to be provided for the generation of feasible trajectories that are conformed to the UAV’s physical limitations.

2.3.5. Total Objective Function

By comprehensively optimizing each constraint, parameters such as path length, threat penalty, flight safety altitude, and path smoothness are balanced, and weights are assigned to each sub-objective, and the weighted sum is obtained to obtain the total objective function, as shown in Equation (18) below:

In Equation (18), represents path length weight factor, threat penalty weight factor, flight safety height weight factor, and path smoothness weight factor, respectively, and in this paper, we take , , , and .

3. Sparrow Search Algorithm

Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), first proposed by Xue et al. in 2020 [

18], is a meta-heuristic intelligent optimization algorithm that achieves global optimization by simulating the foraging and antipredator behaviors of sparrow population. The sparrow population represents its position by a matrix as shown in Equation (19) below:

In Equation (19), n represents the number of individual sparrows and d represents the dimension of the optimization objective variable.

The fitness value can be expressed as

In Equation (20), represents the overall fitness value of the optimization result, while each row represents the fitness value of each individual.

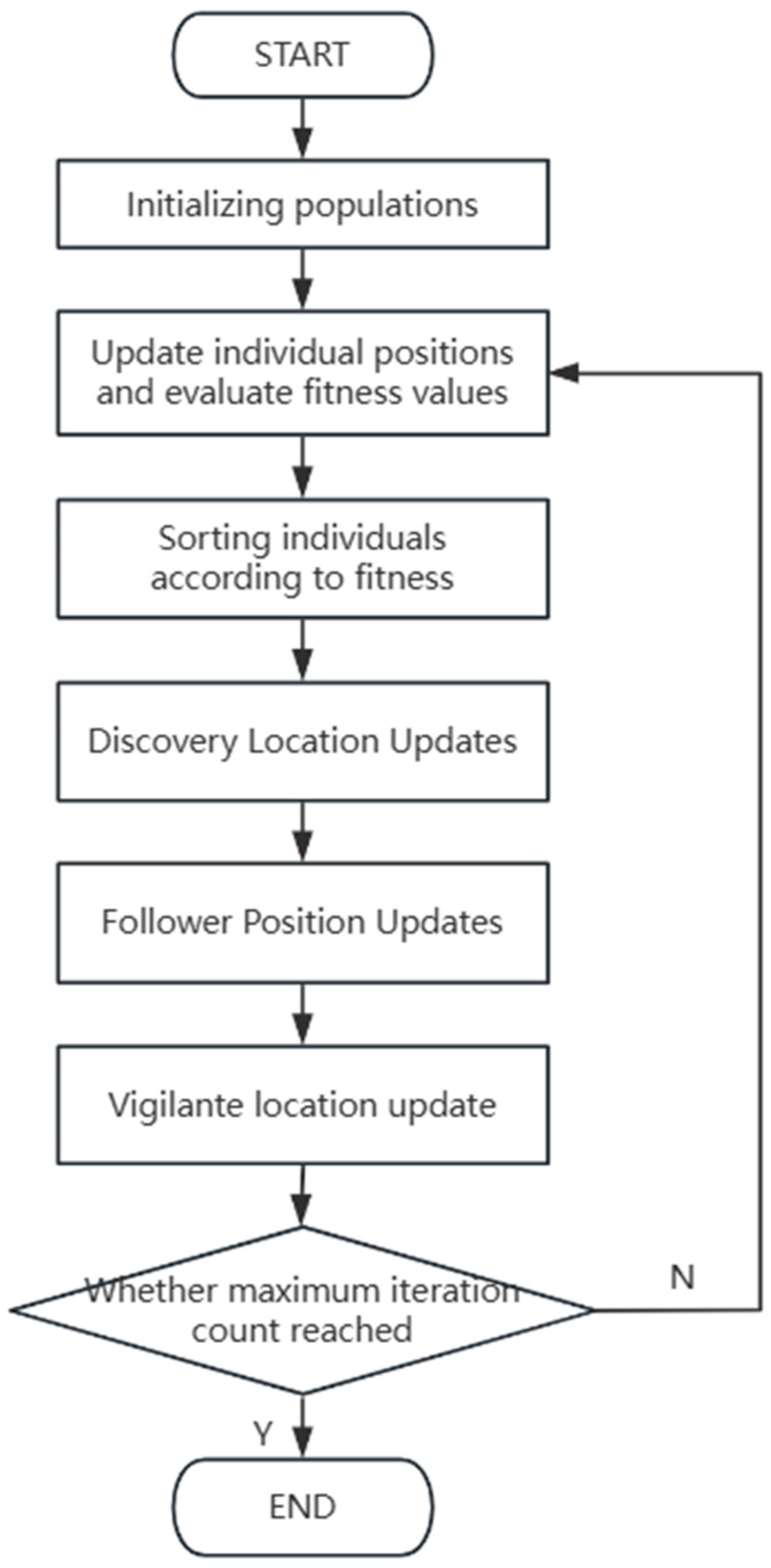

The core mechanism of SSA is composed of three types of roles: discoverers are responsible for exploring new areas and guiding the direction of the population; local exploitation is carried out by followers around the discoverers, while over-concentration of resources is avoided through the competition mechanism; and threats are randomly monitored by vigilantes, and the escape behavior of the population is triggered. A synergistic balance mechanism of exploration–exploitation–risk avoidance is formed by the three parties through information sharing and role transformation.

Producers: Individuals with high adaptability are responsible for global exploration, and their location update is based on the judgment of the environment safety status. When the warning value is assessed to be lower than the safety threshold, the search range is expanded by the producers; on the contrary, migration to safe areas is performed by them. The location update process is mathematically represented in Equation (21) below:

In Equation (21), denotes the number of iterations; ; ; denotes the position of the -th individual in the -th dimension at the -th iteration; the random number ; is a constant, denoting the maximum number of iterations; is a randomized warning value; is a safety threshold; is a disturbance factor obeying the normal distribution; and is a matrix at .

Followers (scroungers): Localized exploitation around the discoverer, competing for access to resources in the premium region. If food is not found by the follower for an extended period (indicating no improvement in adaptation), a random jump to other regions is executed. Their positions are updated as shown in Equation (22) below:

In Equation (22), denotes the global worst position at the -th iteration, and denotes the optimal position information of the discoverer at the iteration. A is a matrix of and each element inside it is randomly selected in and .

Sentries: A randomly selected subset of individuals monitor threats. When a danger is detected (e.g., a path is close to an obstacle), the group escape mechanism is triggered. Their positions are updated as shown in Equation (23) below:

In Equation (23),

is the global optimal position in the

-th iteration; the parameter

controls the step length, and its value obeys the normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1;

is generated according to the uniform distribution, and it controls the direction of movement of each individual;

is the fitness value of the current individual, and

and

are the local optimal and the worst fitness of the current population, respectively;

is the very small constant; and

is optional here. The flow process chart of Sparrow Search Algorithm is shown in

Figure 2.

4. Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm

The original algorithm is characterized by simplicity and ease of implementation, achieved through dynamic collaboration between different roles. The search scope is rapidly narrowed during the early exploration stage, with gradual convergence toward the optimal solution being achieved in the later stage. However, some limitations are still exhibited by the algorithm when applied to high-dimensional problems such as complex trajectory planning. These limitations include insufficient global exploration capability, reliance on a fixed threshold for the discoverer’s position update, and a tendency toward premature convergence. Furthermore, rigid local development is demonstrated, with the follower’s search being confined to a single direction, making it difficult to escape from local optima. Additionally, weak dynamic adaptability is shown, and the alert mechanism proves insufficiently flexible to respond effectively to complex constraints. To address the above problems, the Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) is proposed in this paper, which integrates the sine–cosine function with the Lévy flight mechanism, enhances the global exploration ability through dynamic weight adjustment, breaks through the local extremes using random jumps of Lévy flights, and combines the co-optimization of each role to enhance the algorithm’s efficiency. The precision and robustness of trajectory planning are significantly enhanced by the ISSA, while controllable computational complexity is maintained. Consequently, effective theoretical support is provided for UAV navigation in complex environments.

4.1. Positive Cosine Strategy

A rigid search direction is caused by the fixed parameters of the original SSA. For this reason, the sine–cosine strategy is introduced to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation through a nonlinear weight function. A sine function is used to generate time-varying weights, which are assigned a large value at the initial stage to enhance the global exploration capability, and gradually reduced at the later stage to focus the local exploitation capability. The weight change formula is

In Equation (24), and are the lower and upper limits of the weight range, respectively. Function changes over time, and in the early iteration, as t gradually increases, gradually increases, and will be close to the upper limit, which can realize rapid decay and help the global exploration. Later, as gradually reaches the maximum number of iterations , gradually tends to 0, decreases to the lower limit, and gradually converges gently, helping the local development to avoid the algorithm precocious.

4.2. Improvement of Discoverer Behavior

In the traditional SSA, the movement direction of the discoverer is directly controlled by random numbers, which is easily affected by the initial parameters, and is improved using the sine–cosine function to enhance the global exploration ability of the discoverer and optimize the diversity of the path directions. In the discoverer position update, a in Equation (24) is directly introduced into the discoverer’s position update formula, and the sine–cosine periodicity specificity is borrowed to apply sine and cosine perturbations alternately. The search range is extended horizontally through the sine perturbation, while obstacle avoidance is reinforced in the vertical dimension through the cosine perturbation. A significant enhancement in path diversity is achieved through the combination of these two perturbation strategies. The finder position update formula is improved as

In Equation (25), and are random numbers. It should be noted that is the current path warning value calculated based on the distance of obstacles, flight altitude, etc. When is lower than the safety threshold , it is judged to be a safe environment, and the sinusoidal function is used to perturb the path nodes to expand the horizontal search range. When is judged as an obstacle detected, the threat response is triggered to switch to the cosine function to guide the path and raise or lower the flight altitude along the vertical direction.

4.3. Lévy Flight Mechanism

The Lévy flight mechanism is a special kind of random walking pattern, whose step length is characterized by alternating between “short-range fine search” and “long-range jump”. This mechanism simulates the foraging behavior of birds, where intensive search is conducted in food-rich areas while rapid migration is performed across food-scarce regions. The algorithm’s entrapment in local optima is thereby effectively prevented. The Lévy flight mechanism is shown in Equation (26) below:

In Equation (26),

and

are random numbers within the range of

,

takes the value of 1.5 here, and

is calculated as shown in Equation (27) below:

In Equation (27), .

4.4. Follower Position Perturbation

In the original SSA, over-reliance on the current optimal solution is exhibited by followers, leading to premature group convergence. Following the implementation of the Lévy flight mechanism enhancement, local refinement is initially conducted using short step sizes. In regions exhibiting better adaptation, path adjustments around the discoverer are executed by followers through short-step movements, thereby optimizing both turning angles and climbing efficiency. If the path cost does not improve for many consecutive generations, a Lévy long-step jump will be triggered, causing some of the followers to migrate to a new region. For example, when dense obstacles are encountered, “dead ends” can be effectively crossed by the drone through the utilization of long-stride movements. Finally, the Lévy parameter is adaptively adjusted according to the complexity of the environment to increase the probability of long stride length in dense obstacle areas, and vice versa to enhance local exploitation. The improved follower formulation is shown in Equation (28) below:

In Equation (28), is the position of the worst individual at the -th iteration; is the optimal position currently occupied by the discoverer; and denotes the product of each component of the random vector of the Lévy distribution by its elements by multiplying it with the corresponding component of .

4.5. Improvement of Algorithm Flow

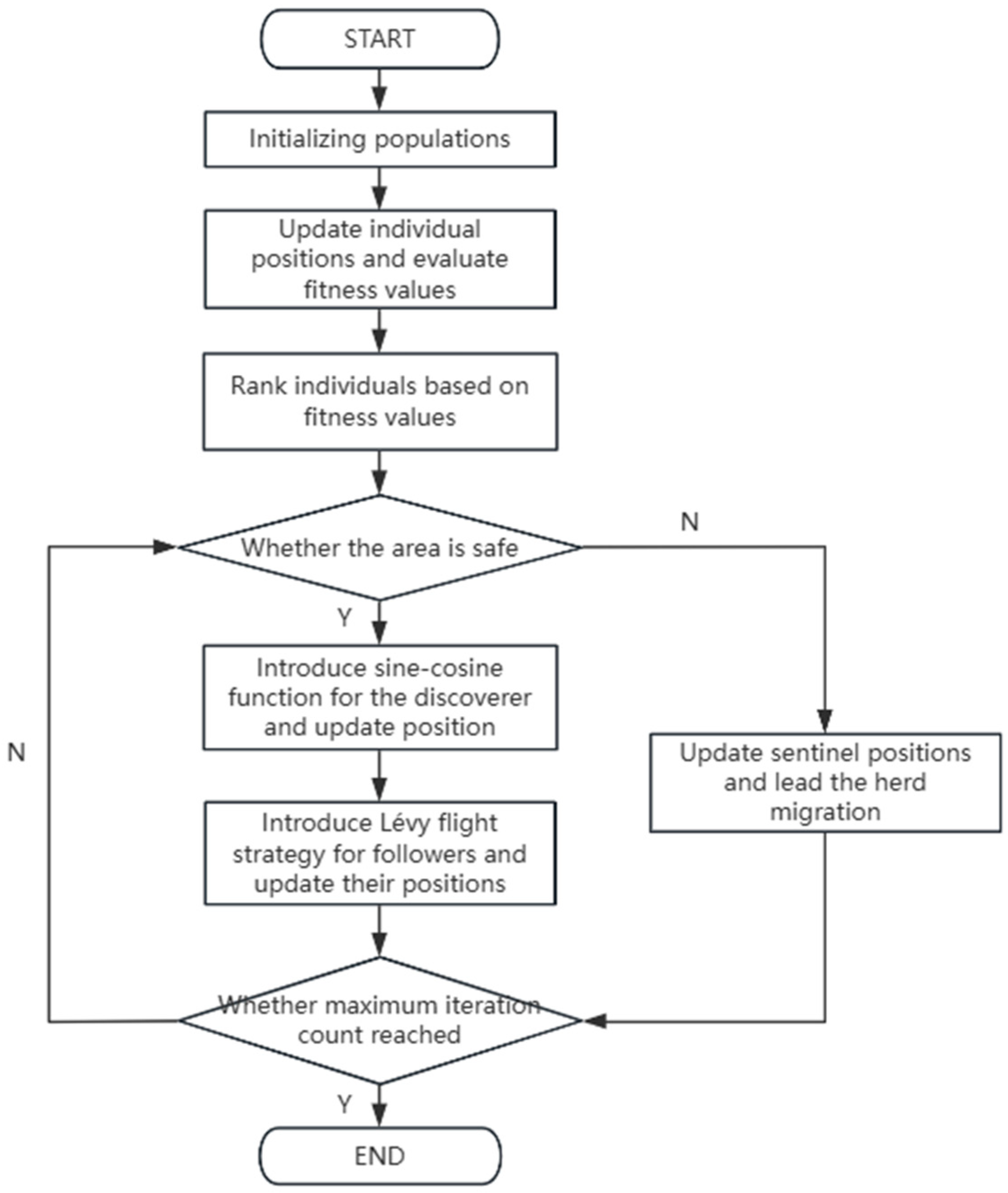

Aiming at the current problems of traditional SSA, an Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) based on the sine–cosine strategy and the Lévy flight strategy is proposed in this section, which effectively alleviates the shortcomings of the original SSA that is easy to converge prematurely and fall into the local optimum. The algorithm so improved is more in line with the behavioral patterns of the real sparrow populations in complex environments. The position of the individuals is realized by adopting the strategy of sine–cosine search, so that the search process has a stronger ability to jump out of the local optimal solution, which enhances the global exploration ability and population diversity of the algorithm. Meanwhile, the local exploitation accuracy in the later stages of the search is strengthened by the introduction of the Lévy flight mechanism, and the convergence accuracy and stability of the algorithm are improved through the use of nonlinear decay parameters to control the magnitude of the search. In addition, an adaptive perturbation mechanism is introduced by ISSA during population evolution, through which the search trajectories of excellent individuals are effectively optimized, global exploration and local exploitation are balanced, and the robustness of the algorithm is consequently enhanced. As a whole, significant advantages are demonstrated by ISSA in terms of population initialization uniformity, search path flexibility, population diversity maintenance, convergence speed, and accuracy, along with capabilities for escaping local optima and adapting to complex environments.

The specific steps of the algorithm improvement are implemented as follows: During the initialization phase, parameters including population size, maximum iteration count, and safety threshold are configured. The initial path population is randomly generated while ensuring compliance with safety constraints at both the starting and ending points. The adaptation degree of each individual’s path is calculated and ranked, with the top 20% classified as discoverers, the bottom 10% as vigilantes, and the remaining individuals designated as followers. In the iterative optimization phase, when a path region is determined to be safe, path nodes of discoverers are first adjusted using the sine–cosine strategy to prioritize exploration of uncovered regions. Subsequently, paths of followers are perturbed through Lévy flight integration, achieving balance between exploitation and escape behaviors. Vigilantes were emphasized to redirect when areas on the path were judged unsafe. For each generation of the population, the optimal path is retained to prevent the optimization from backtracking; finally, it terminates when the maximum number of iterations is reached, and outputs the globally optimal path and its cost metrics. The specific process is shown in the following

Figure 3.

5. Simulation Verification and Result Analysis

5.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

In order to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) in complex 3D UAV trajectory planning, the experiments are run under the AMD Ryzen 7 5800H, 16 GB RAM, and RTX 3060 hardware platforms, and MATLAB R2019b is used as the core development platform to construct a high-precision and multi-functional simulation environment, which takes into account the efficiency of the algorithms and the complex scene. The simulation environment is built with high precision and multi-functionality, taking into account the efficiency of the algorithm and the needs of complex scenes.

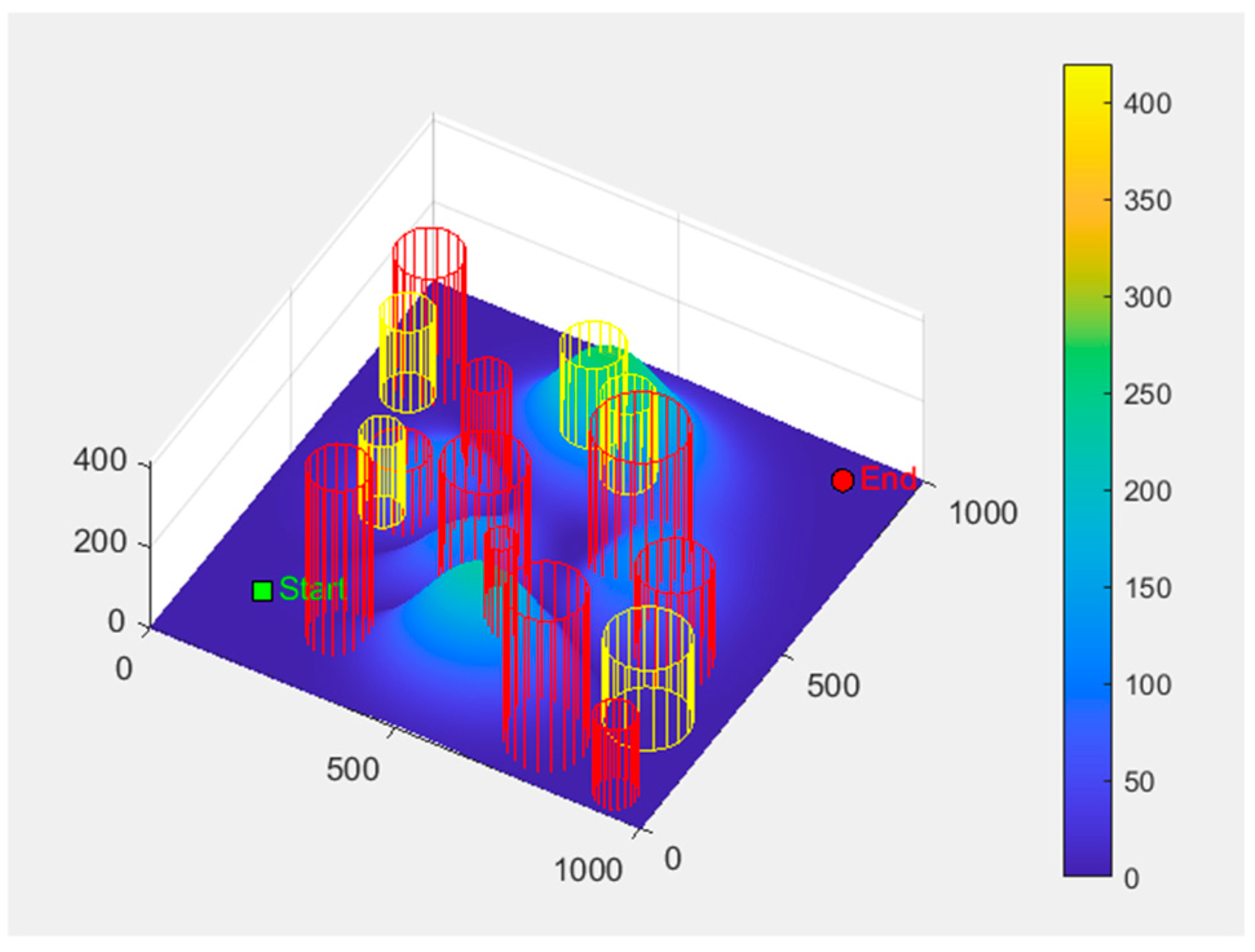

The simulation scenario is selected to simulate a mountainous environment with a terrain range of 1000 × 1000 × 500. Ten cylindrical static obstacles are randomly distributed across this terrain, with radius ranging from 30 to 100 units and heights from 100 to 450 units. Five no-fly zones are established, each with an influence radius of 40–80 m and a vertical range of 100–200 m. The starting coordinates are set to (200, 50, and 150), and the ending coordinates to (950, 800, and 150). Both locations are situated in gentle terrain areas within obstacle-free takeoff and landing safety zones, ensuring the algorithm could fully test obstacle avoidance capabilities. Detailed parameter settings for the environmental terrain, obstacles, and no-fly zones are shown in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The obstacle matrix is defined in this paper:

The no-fly zone matrix is defined in this paper as shown below:

In order to make the threat area as well as the start point and end point distinguished more intuitively from the terrain in the simulated 3D environment scene. The red striped cylinder model is used here to represent the static obstacles. The yellow striped cylinder model is used to represent the no-fly zone. The start point and the end point are represented using the green squares and the red dots, respectively. The specific UAV 3D environment scene model is shown below in

Figure 4:

For ISSA in the UAV 3D trajectory planning problem, the key parameter configuration is shown in

Table 4:

5.2. UAV Trajectory Planning Based on Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm

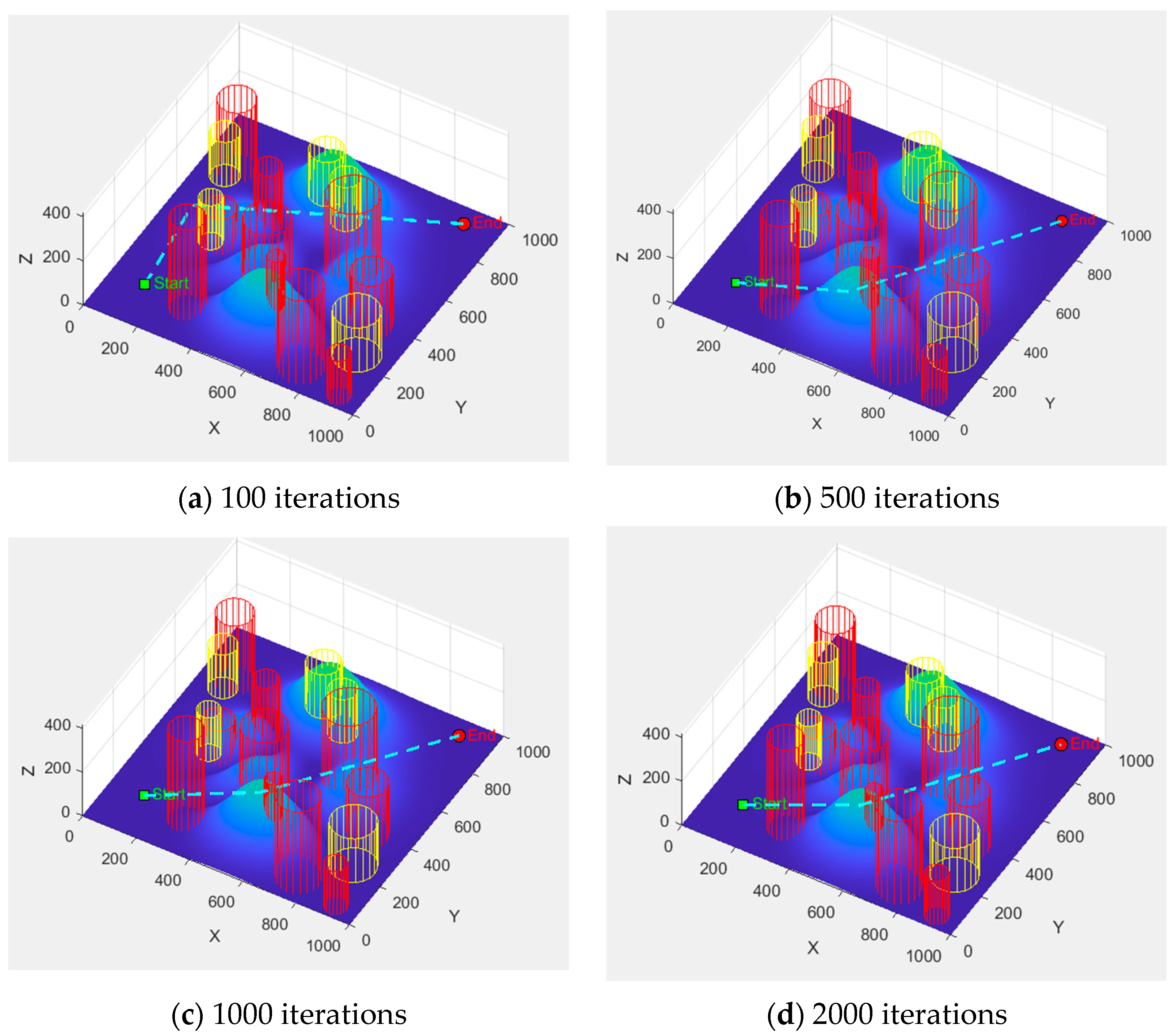

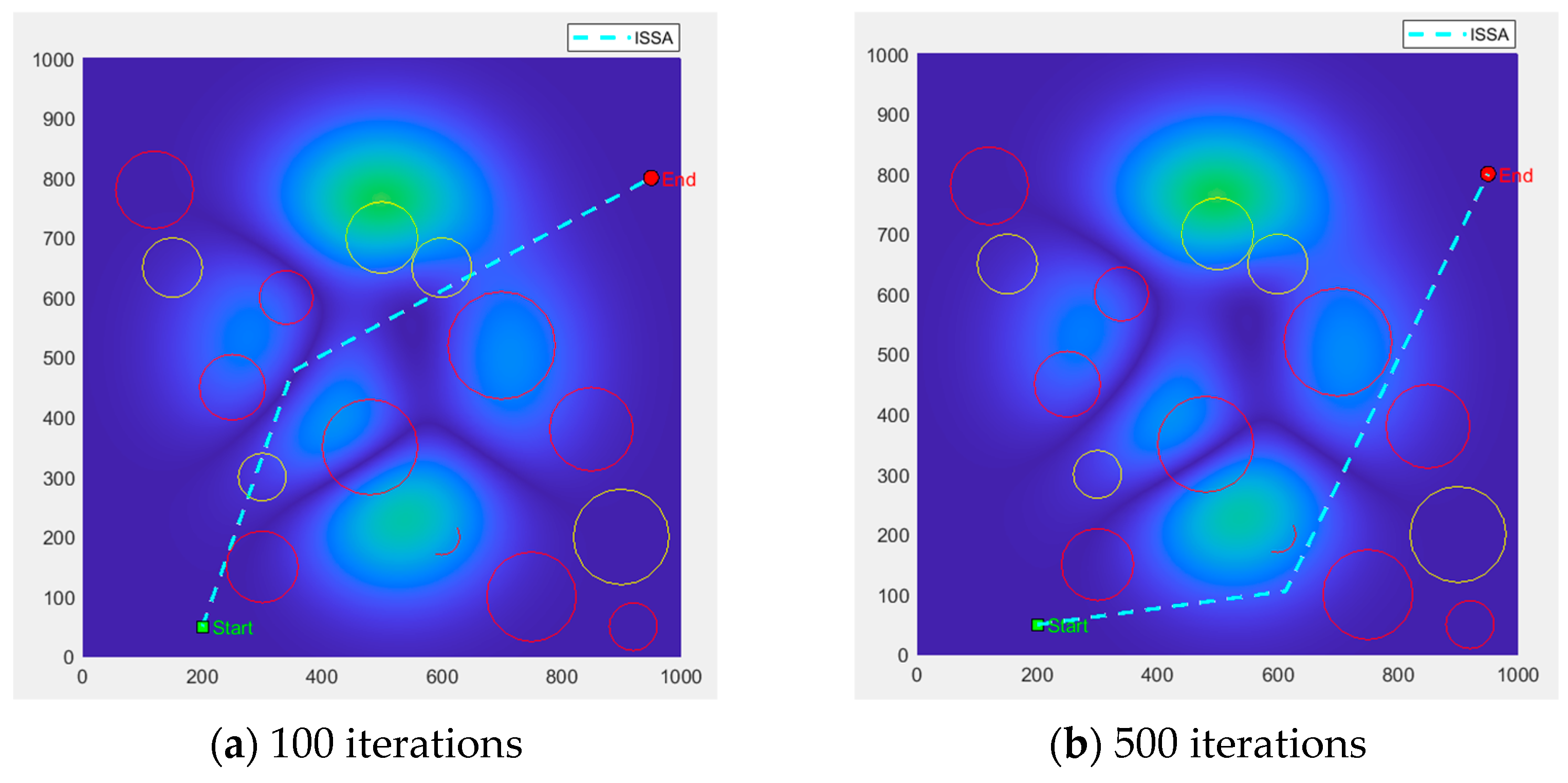

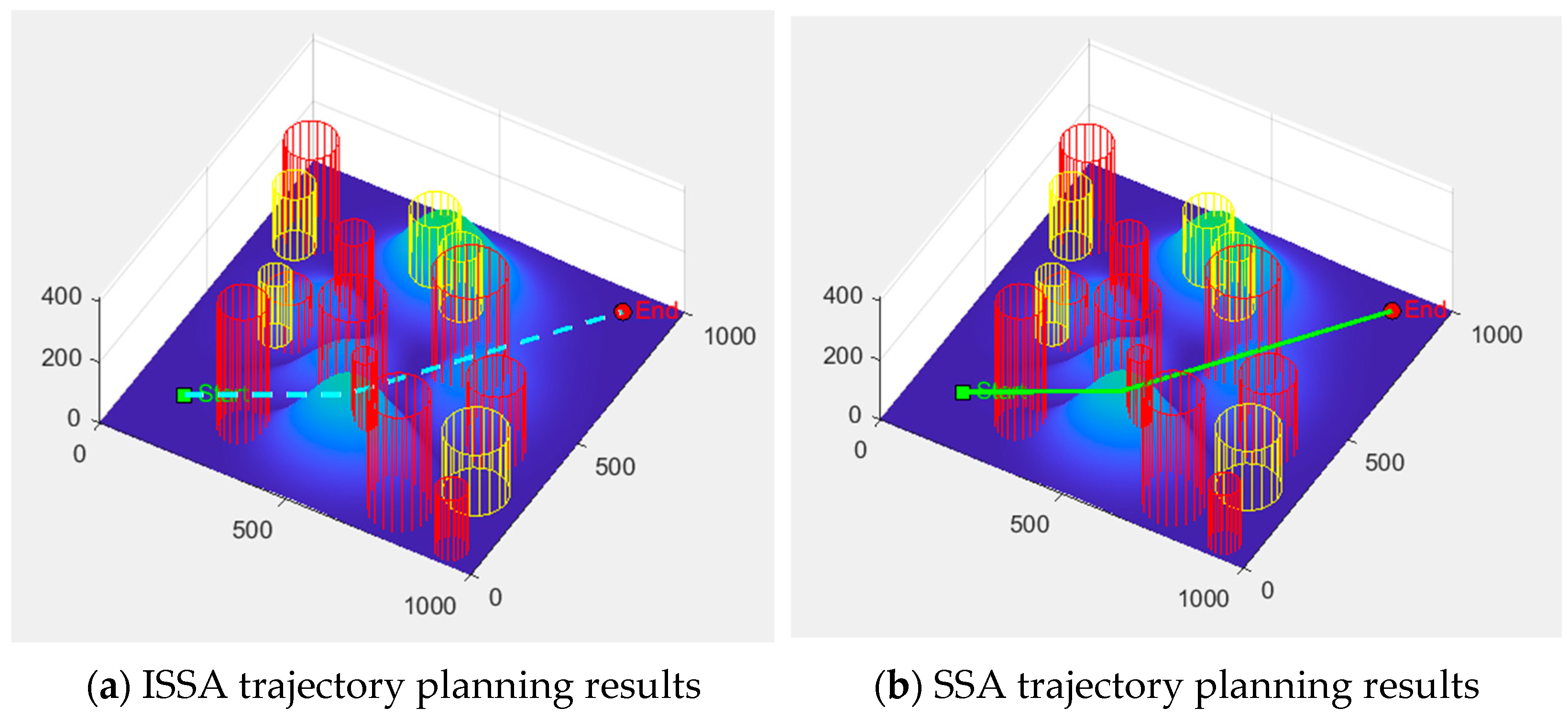

In the experimental design of this paper, the maximum number of iterations is set to 2000 iteration steps. Based on this, the path optimization results generated by ISSA in a 3D scene containing obstacles and threat zones are presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. These results demonstrate the evolutionary process across different iteration stages (100, 500, 1000, and 2000 iterations), where the 3D flight trajectory is represented by the cyan dashed line in all visualizations.

From the side view and top view, it can be clearly observed that with the increase in iterations, the flight trajectory generated by ISSA gradually tends to be smoother. Meanwhile, more accurate obstacle avoidance is demonstrated, highlighting the algorithm’s capability to effectively balance path length with flight safety and trajectory continuity. With increasing iterations, the path length is progressively shortened, altitude and threat constraints are more effectively satisfied, and flight trajectories that are economical, safe, smooth, and stable within complex 3D environments are ultimately generated. Thus, strong potential for practical UAV engineering applications is demonstrated by the ISSA algorithm.

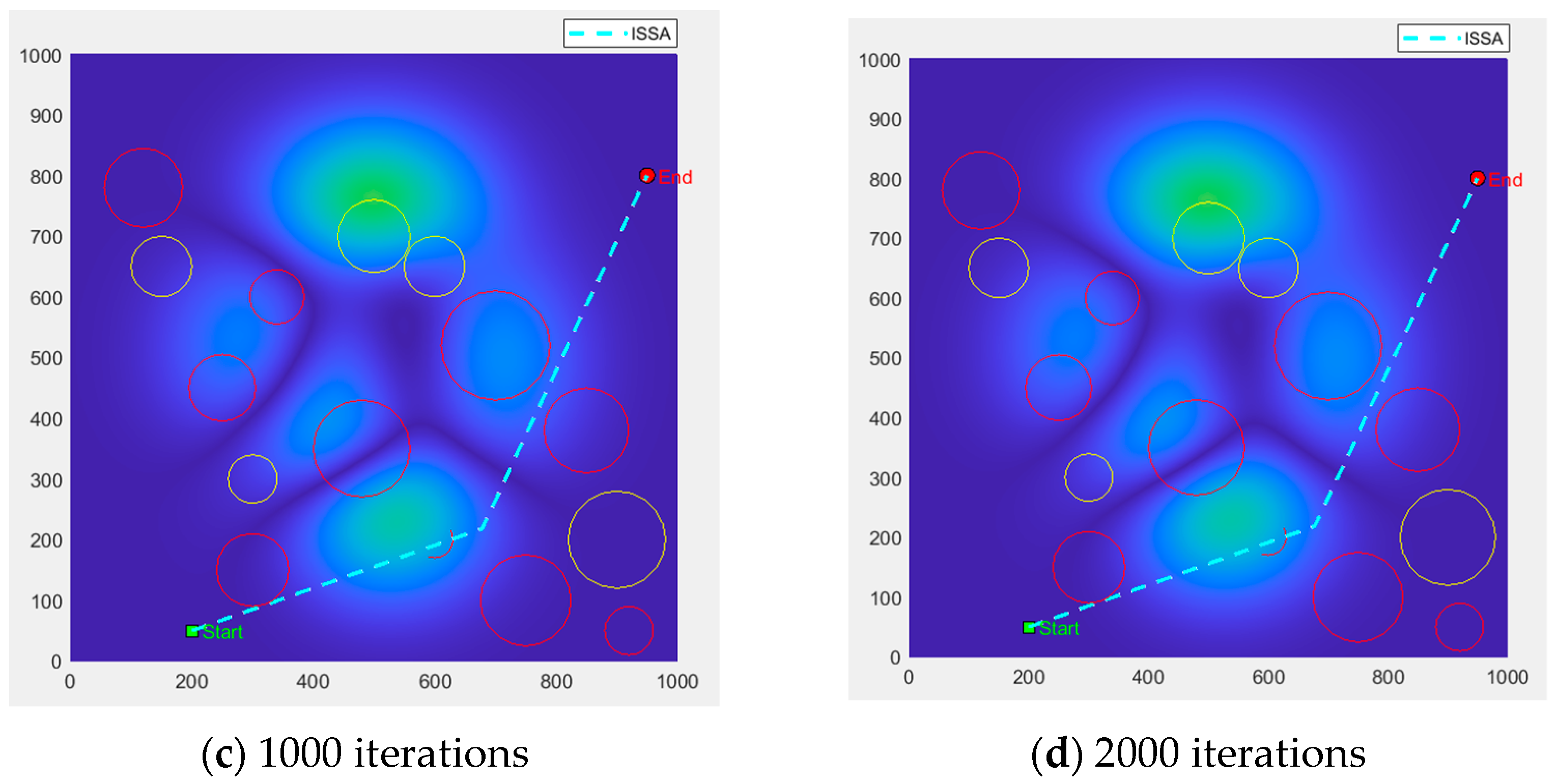

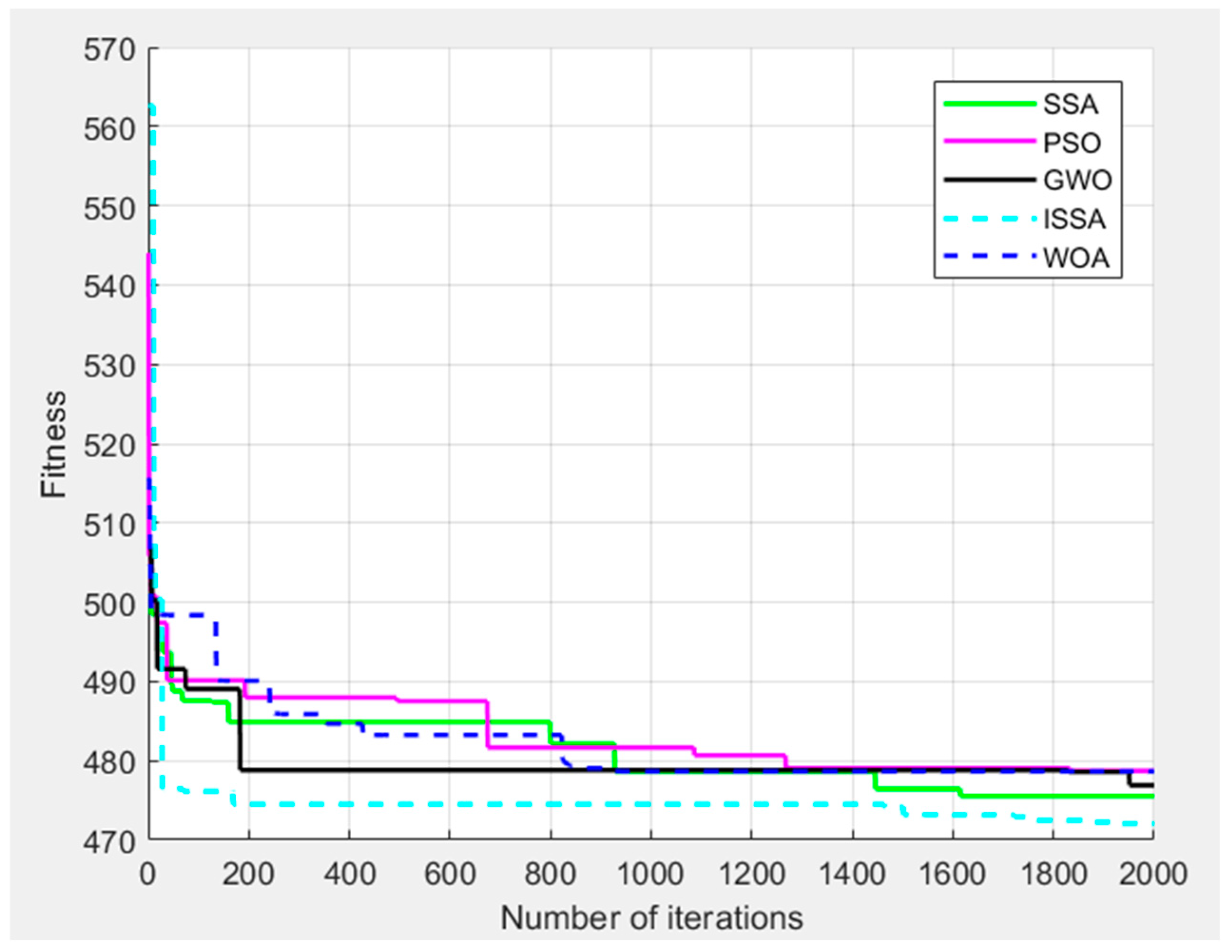

The convergence process of ISSA over 2000 iterations is presented in

Figure 7, where the horizontal axis represents the number of iterations and the vertical axis indicates the fitness value of the objective function. A stepwise decrease is exhibited by the curve, while the overall trend remains smooth and stable, reflecting the dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation achieved by the algorithm.

From the above experimental results, it can be seen that ISSA shows its advantages in convergence efficiency and stability: fast convergence for global search in the early stage, and refined exploration to reflect the local development accuracy in the later stage, which makes the algorithm able to find high-quality solutions with a limited number of iterations in trajectory planning problems in complex environments, and provides an intuitive and reliable basis for practical engineering applications and subsequent optimization of the algorithm.

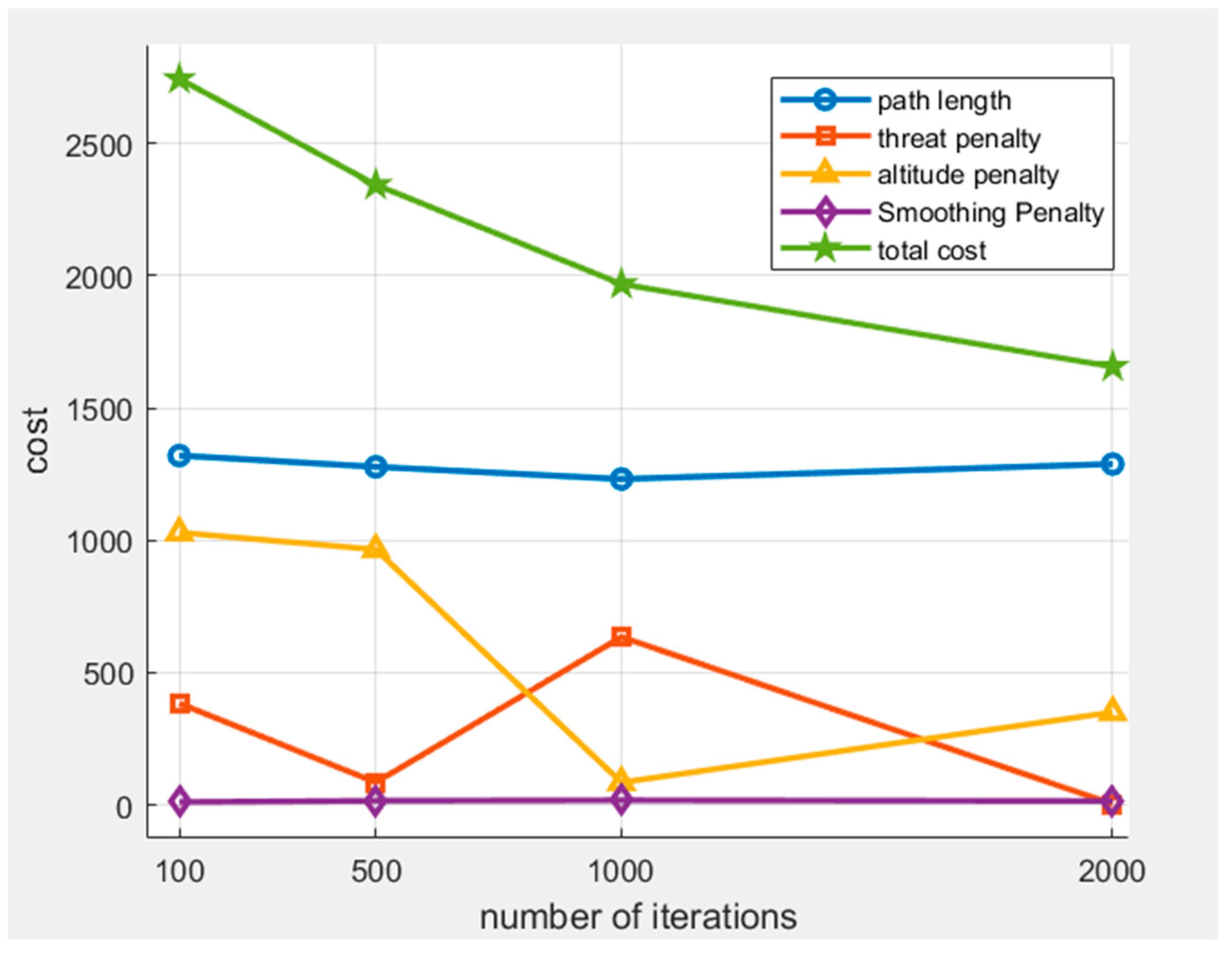

Based on the optimization results of ISSA for the UAV 3D trajectory planning problem, in-depth statistics and analysis of five key cost metrics after 100, 500, 100, and 2000 iterations, path length cost, threat penalty cost, height penalty cost, smoothing penalty cost, and total cost, are presented here. The data are summarized in

Table 5, and the weight changes of each metric in different iteration generations are visualized in the form of line graphs in

Figure 8.

By comparing the cost changes in different iteration stages, it can be seen that the adaptive convergence process of the algorithm under the constraints of the objective function: during the initial 500 iterations, primary focus is placed on global exploration and threat avoidance, where path economy cost is rapidly reduced through the global jumping mechanism; in the 500–1000 iteration phase, the algorithm transitions to localized refinement, with altitude penalty costs decreasing significantly, demonstrating effective optimization of flight altitude constraints, while total cost continues to decline despite minor increases in threat penalty costs; and during the 1000–2000 iteration stage, comprehensive optimization is achieved by the algorithm through synergistic multiple mechanisms, resulting in the generation of a high-quality path that effectively balances economy, safety, and flight stability. The powerful search capability of ISSA in complex 3D obstacle environments is sufficiently verified by the experimental results, through which an efficient and safe solution for UAV autonomous flight trajectory planning is provided. Furthermore, an empirical basis for further research on dynamic weight adjustment and local refinement strategies is established, laying a reliable foundation for efficient autonomous flight of UAVs in complex mission scenarios.

5.3. Comparison of Different Algorithms

5.3.1. Comparison of Simulation Results

In order to ensure that the experiments are compared under a unified situation, five typical population intelligence optimization algorithms, namely Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA), Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm (PSO), Gray Wolf Optimization Algorithm (GWO), and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) are selected and conducted a comparative experiment to test their performances in the same scenario. The population size of each algorithm is set to 100, the maximum number of iterations is set to 2000, and the convergence condition is judged to reach the maximum number of iterations. The critical parameter settings specific to each algorithm are shown in the following

Table 6:

In the algorithmic framework of the sine–cosine function, the parameter a is used to control the perturbation amplitude of the sine and cosine, which is initially taken as 0.9, and linearly decreases to 0.4 in the iterative process. The search step length of the discoverer is expanded by a larger value of parameter a, thereby enhancing the global exploration capability. As the value of a decreases, the perturbation amplitude is gradually reduced, facilitating localized fine search during later optimization stages.

The Lévy flight factor is a key parameter used in the Lévy flight mechanism to generate the random step size, which mainly controls the jump distance distribution and usually takes the value of (1, 2) interval. A longer flight step is generated by a smaller value, through which the global jumping ability is enhanced and premature convergence is effectively avoided by the algorithm. Conversely, a more concentrated flight step is produced by a larger value, enabling localized fine-tuning tendencies and consequently improving convergence accuracy. Through pre-experimentation conducted in this study, the optimal balance between global exploration and local exploitation is determined to be achieved by the algorithm when = 1.5.

The discoverer proportion in SSA is used to control the proportion of discoverers in the total population, and in this paper, the top 20% of individuals are taken to take the role of discoverers, responsible for leading the global search. Enhanced early global exploration is facilitated by a larger discoverer proportion, though this simultaneously reduces the number of followers and consequently affects local exploitation capability. The opposite effects are observed with a smaller discoverer proportion. The early warning value of ST = 0.8 indicates that exponential updating with faster convergence is employed with 80% probability, while random perturbation for escaping local optima is applied with 20% probability.

The proportion of particle velocity retained along the inertia direction is determined by the inertia weight τ in PSO. A value of 0.9 is initially adopted to ensure a substantial search range, which is subsequently reduced to 0.4 at the final stage to enhance convergence speed. This parameter configuration ensures that particles are capable of both rapidly traversing large search spaces and effectively converging within the optimal region. The cognitive factor and the social factor are uniformly taken as 2, which can not only show better convergence speed and stability of the solution, but also avoid excessive oscillation or premature convergence.

In GWO, the current optimal, suboptimal, and third-best solutions are represented by α, β, and δ, respectively, which collectively guide the population movement. Similar to the parameter a in ISSA’s sine–cosine function, the coefficient b serves to dynamically balance wide-area exploration and local exploitation. A certain degree of population diversity is maintained by the algorithm even when the linear decrease in b terminates at 0.5.

In WOA, the linear convergence factor φ decreases from 2 to 0 during iterations, governing the transition from global exploration to local exploitation. The helix constant η is fixed at 1 to define the spiral shape during the bubble-net attacking phase. The strategy selector ρ is set to 0.5, determining whether the algorithm employs encircling prey or spiral updating mechanisms. This parameter configuration enables WOA to effectively balance exploration and exploitation through simulated whale foraging behaviors, avoiding premature convergence while maintaining strong global search capability.

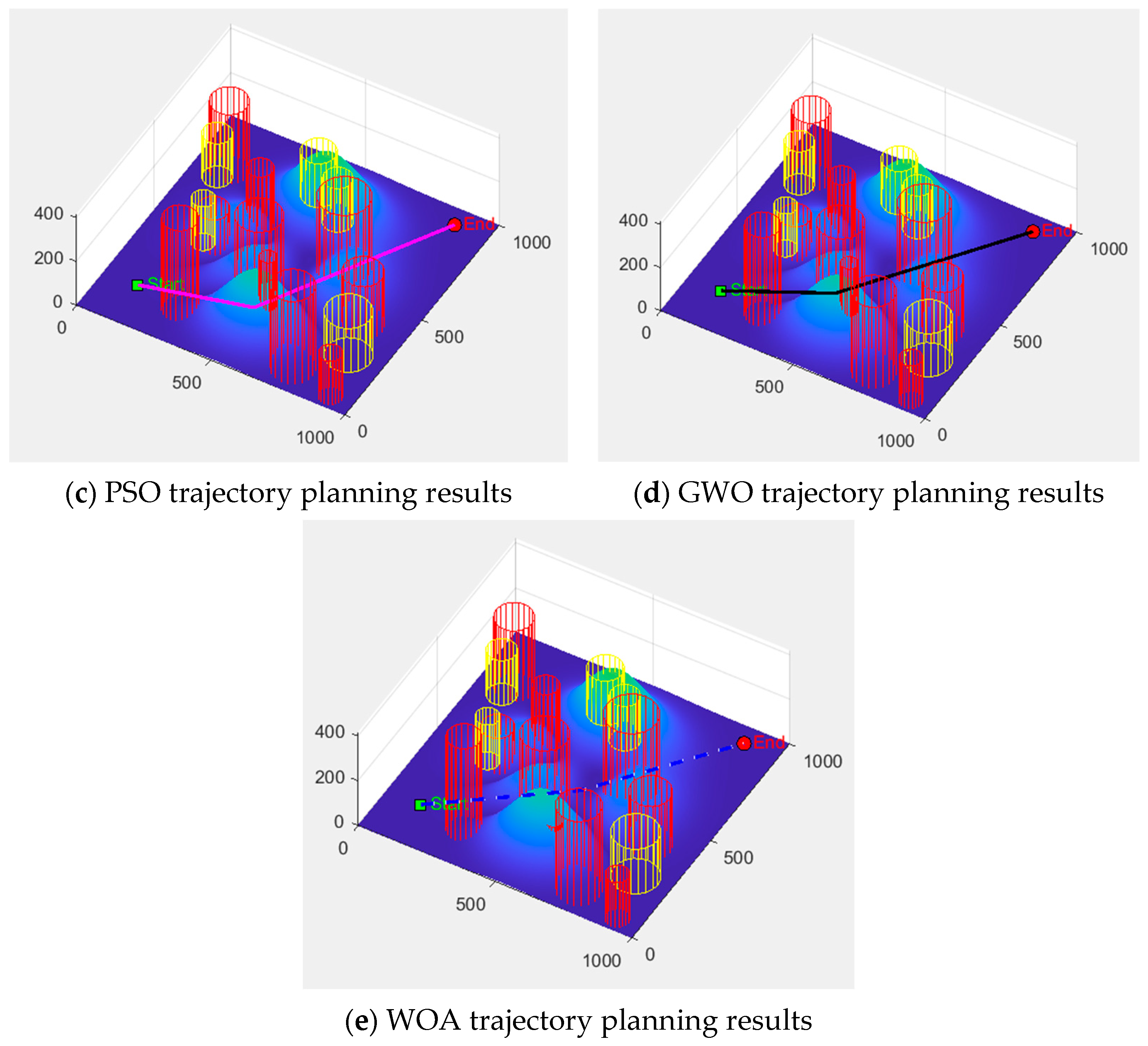

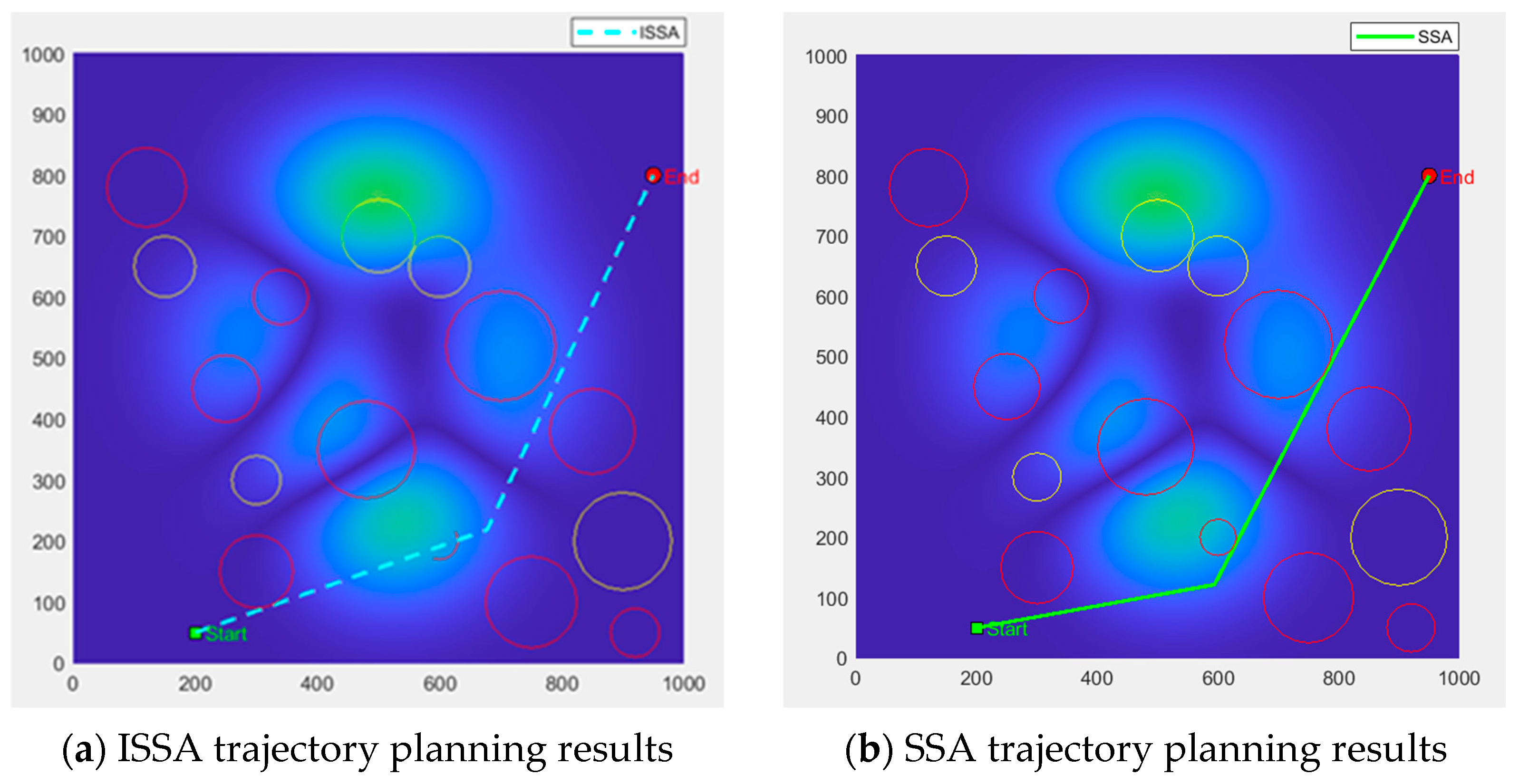

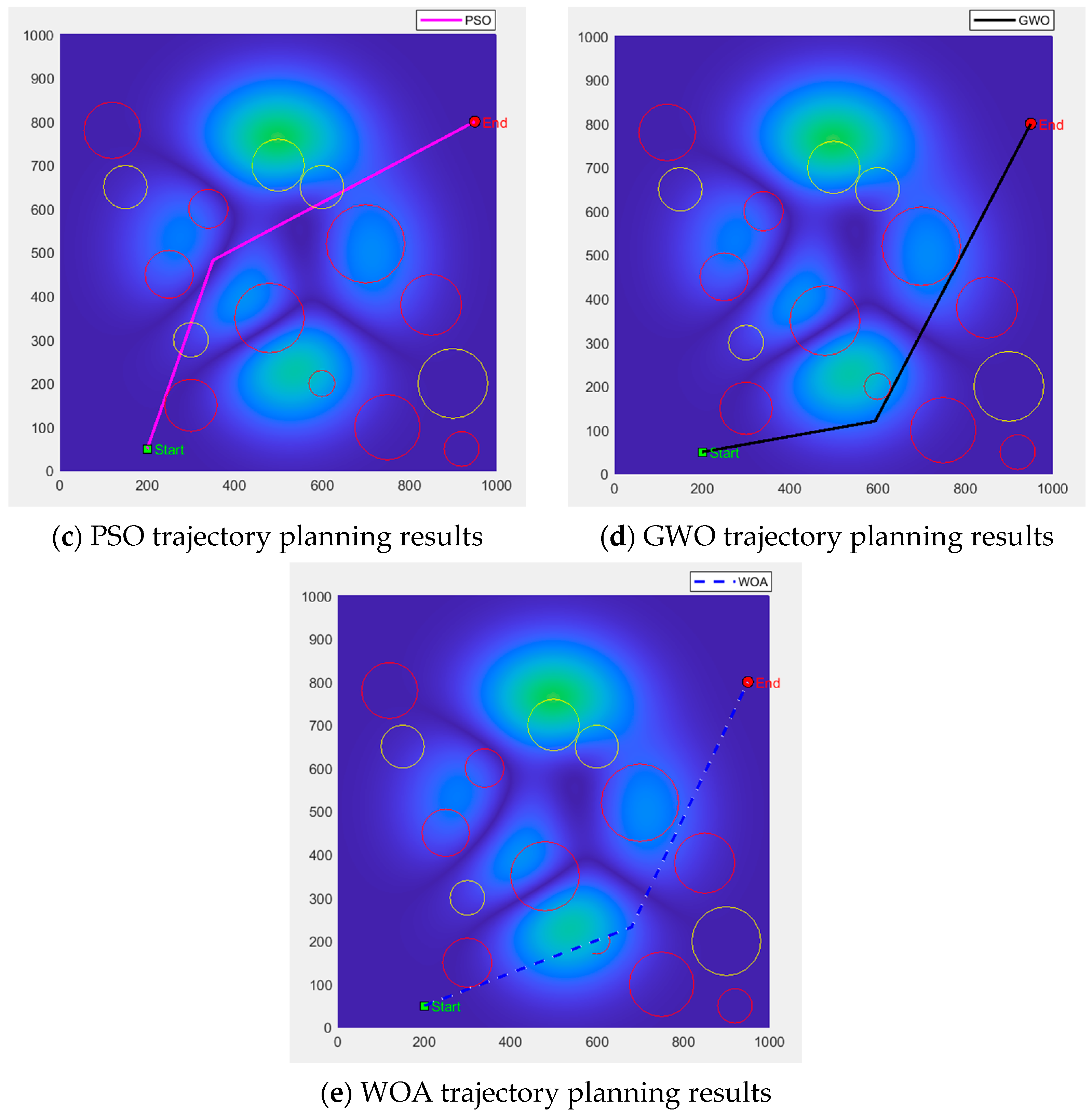

From

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, obstacle avoidance flight trajectories are successfully generated by PSO, GWO, and WOA under the same simulation environment, with their paths maintaining certain distances from obstacles. However, in areas characterized by dense obstacle clusters, the trajectories are observed to approach closer to obstacle boundaries, revealing insufficient potential safety margins. This limitation exposes the fundamental shortcomings of both algorithms regarding their restricted global search depth. Although obstacle avoidance is generally achieved by SSA, significantly inferior path smoothness is exhibited compared to ISSA, primarily due to the presence of hard folding lines at critical turning points. In contrast, smoother path curves are generated by ISSA, featuring natural connections at turning points and even distribution through obstacle fissure zones. Effective avoidance of threatening areas is achieved while maintaining adequate safety buffer distances, particularly in regions characterized by high obstacle density. The advantages of ISSAs stem from its synergistic mechanism of positive cosine and Lévy flight: large step-length jumps for crossing obstacles are provided by the former during global exploration phases, while fine search for optimizing curve smoothness is enabled by the latter during local exploitation phases. Dynamic adjustment of individual obstacle avoidance responses is achieved through the hybrid producer–follower–vigilant updating strategy, thereby further enhancing safety performance.

Comprehensive comparison demonstrates that under identical iteration counts, faster convergence is achieved by ISSA alongside the acquisition of shorter and smoother paths. Furthermore, superior performance is exhibited over PSO, GWO, SSA, and WOA in both obstacle avoidance efficiency and safety margins. These results reflect the enhanced algorithm’s exceptional capability to balance economy and safety within complex three-dimensional environments.

Due to the use of random number, metaheuristic algorithm results always vary significantly. Thus, 50 independent loop executions have been performed under the exact same scenarios. Following

Table 7 are the statistical results. From the results, it can be observed that ISSA outperforms the others in terms of average fitness and stability.

5.3.2. Convergence Performance Comparison

In UAV path optimization problems, the advantages and disadvantages of optimization algorithms, along with their computational efficiency, are directly determined by convergence performance. In order to evaluate the performance of different algorithms in the convergence stage, four algorithms, ISSA, SSA, PSO, GWO, and WOA, are selected in this paper, and their final fitness values after satisfying the preset convergence conditions are compared and analyzed, and the results are shown in

Figure 11.

The experimental results indicate that superior performance in complex environment trajectory planning is demonstrated by ISSA through its fast convergence characteristics, excellent global search capability, and balanced local development. Not only are better solutions identified during early stages, but steady improvement is also maintained in later iterations, ultimately achieving the lowest fitness levels. In contrast, varying degrees of slow early convergence and later-stage stagnation are exhibited by SSA, PSO, GWO, and WOA. These results sufficiently demonstrate that higher reliability and practical value are possessed by ISSA for UAV 3D path optimization tasks, while a solid foundation is established for subsequent practical applications and algorithmic enhancements.

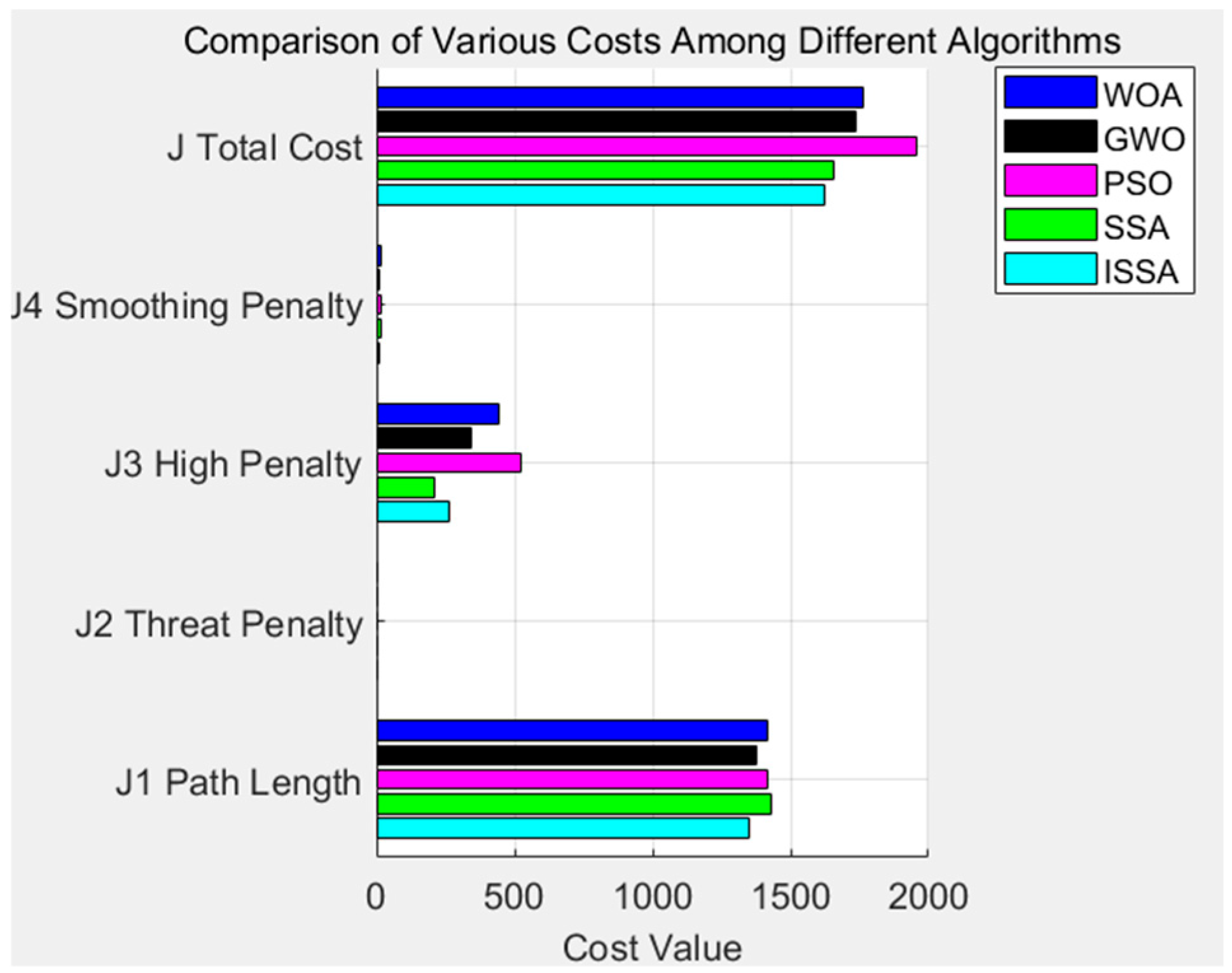

5.3.3. Flight Cost Optimization Analysis

In order to comprehensively evaluate the optimization ability of the four population intelligence algorithms in the UAV 3D trajectory planning task, the five cost indicators of the Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA), the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), the Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm (PSO), the Gray Wolf Optimization Algorithm (GWO), and the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) are analyzed for their respective 2000 iterations, the path length cost, the threat penalty cost, the high penalty cost, and the smoothing penalty cost, and total cost is systematically counted and the results are compared as shown in

Figure 12.

The absolute advantage is held by ISSA, achieving the lowest total cost value among the five compared algorithms. In order to quantify the performance difference among the algorithms, the total cost reduction achieved by ISSA relative to other algorithms is calculated: approximately 1.9% compared to SSA, 20.4% compared to PSO, 6.8% compared to GWO, and 9.7% compared to WOA. These quantified improvements demonstrate ISSA’s exceptional capability in balancing comprehensive optimization objectives. The experimental results demonstrate that ISSA can more effectively balance path economy, safety, and flight stability in complex, obstacle-laden 3D environments. Solid theoretical support for the autonomous flight of UAVs in complex scenarios is provided by the algorithm’s excellent performance, and promising directions for future algorithmic enhancements and engineering applications are also indicated.

5.3.4. Computation Complexity Comparison

Computational complexity analysis is critical as this directly determines the algorithm’s feasibility for real-time UAV path planning. The complexity of ISSA is influenced by several key parameters: the population size

, the dimensionality of the problem

, and the maximum number of iterations

. Based on these factors, the overall computational complexity of ISSA can be derived as follows:

The computational complexity of the Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) is determined by three core parameters: population size n, problem dimensionality d, and the maximum number of iterations T. These parameters must be selected to align with the practical requirements of UAV trajectory planning. In the three-dimensional UAV trajectory planning scenario of 1000 × 1000 × 500 used in this paper, which features 10 obstacles and 5 no-fly zones, the number of trajectory waypoints is set to 20. This number is considered optimal as it sufficiently addresses constraint requirements while balancing trajectory accuracy against computational efficiency. The population size n is set to 100, the problem dimensionality d is calculated as 3 × 20 = 60 (as each waypoint contains x, y, z coordinates), and the maximum iteration count T is set to 2000.

The computational complexity of the ISSA algorithm is defined as O (T⋅n⋅(d + log n)). The computational load is primarily constituted by trajectory waypoint coordinate updates (the dimensional term O (T⋅n⋅d)) and population sorting (the term O (T⋅n⋅log n)). Based on these calculations, the total computational load of the ISSA algorithm is estimated at approximately 1.36 × 107 basic operations. A breakdown of these totals reveals that the core update operations—comprising the coordinate updates for discoverers, followers, and vigilantes—account for a computational load of 1.2 × 107, representing the largest share at over 88%. The sorting operation accounts for 1.4 × 106, meaning the additional computational overhead introduced by sorting comprises about 6.1% of the total.

When compared with algorithms such as SSA, PSO, GWO, and WOA, it is observed that ISSA shares the same theoretical complexity order as SSA. However, due to enhanced modules like the sine–cosine strategy and Lévy flight, its actual computation time is found to be 10%~15% higher. Compared to PSO, GWO, and WOA, which lack sorting operations and possess a complexity of , the theoretical complexity of ISSA is approximately 6.1% higher.

To further explore the computational complexity of ISSA, a comparison is conducted with several widely used algorithms, including SSA, PSO, GWO, and WOA. The complexities of SSA, PSO, GWO, and WOA are characterized as , which indicates that the computational effort is primarily constituted by the processes of population initialization, fitness evaluation, and position update. This increase in complexity, however, is justified by significant performance gains. Experimental results demonstrate that although a single run of ISSA requires slightly longer computation time (1.0~1.2 s), the total trajectory cost achieved (1964.88) is 0.4% lower than that of SSA and 3.2% lower than that of PSO. More importantly, a 100% obstacle avoidance success rate is achieved by ISSA, which is 8% and 12% higher than that of SSA and PSO, respectively. In contrast, algorithms like PSO and GWO, despite their lower complexity, are prone to planning failures due to premature convergence or insufficient local search. The standard SSA, lacking effective enhancement mechanisms, struggles with complex terrain and multiple constraints. However, for dynamic optimization scenarios, rapid response and adaptation are better supported by algorithms such as PSO, GWO, and WOA, owing to their more simplified iterative update strategies, which allow for quicker solution adjustments in changing environments. In conclusion, a superior balance between computational consumption and trajectory performance is achieved by the ISSA algorithm through a deliberate and moderate increase in complexity, leading to comprehensive improvements in trajectory safety, economy, and planning success rate in complex 3D scenarios.

6. Conclusions

Based on the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), an Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) is proposed through a synergistic mechanism integrating sine–cosine function and Lévy flight. This enhanced algorithm effectively balances global exploration and local exploitation while addressing the local optima problem and improving boundary constraint handling. In simulation experiments, ISSA is demonstrated to generate trajectories that outperform those of SSA, PSO, GWO, and WOA algorithms while satisfying all constraints. The planned path is characterized by cost-effectiveness, smoothness, and sufficient safety margins. Comparative results show that ISSA rapidly reduces the total cost during early iterations, maintains balanced search in mid-iterations, and achieves fine adjustment in later stages, ultimately attaining superior convergence performance and solution quality.

Despite its advantages, the improved algorithm has certain limitations. First, all simulation scenarios assume static obstacle regions, which may differ greatly from real-world scenarios. We need to focus on incorporating additional influencing factors and extending the method to dynamic environments; second, some critical parameters involved are preset according to experience or the publicly available literatures, such as cost function weight, Lévy flight factor λ, and nonlinear weight a, lacking systematic parameter sensitivity analysis and adaptive optimization schemes. Third, comprehensive parameters sensitivity analysis and optimization is a very promising future direction. Lastly, different types of algorithms, such as transformer-combined and CNN-based algorithms developed in recent years, need to be included to make a more complete comparison dimension. In summary, the proposed ISSA algorithm can accomplish the balance between global search and local development, which is able to plan a UAV trajectory that is better than SSA in simulation experiments while meeting various constraints. Extensive experiments confirmed that the proposed method is competitive, adaptive, and applicable to varied UAV trajectory planning.