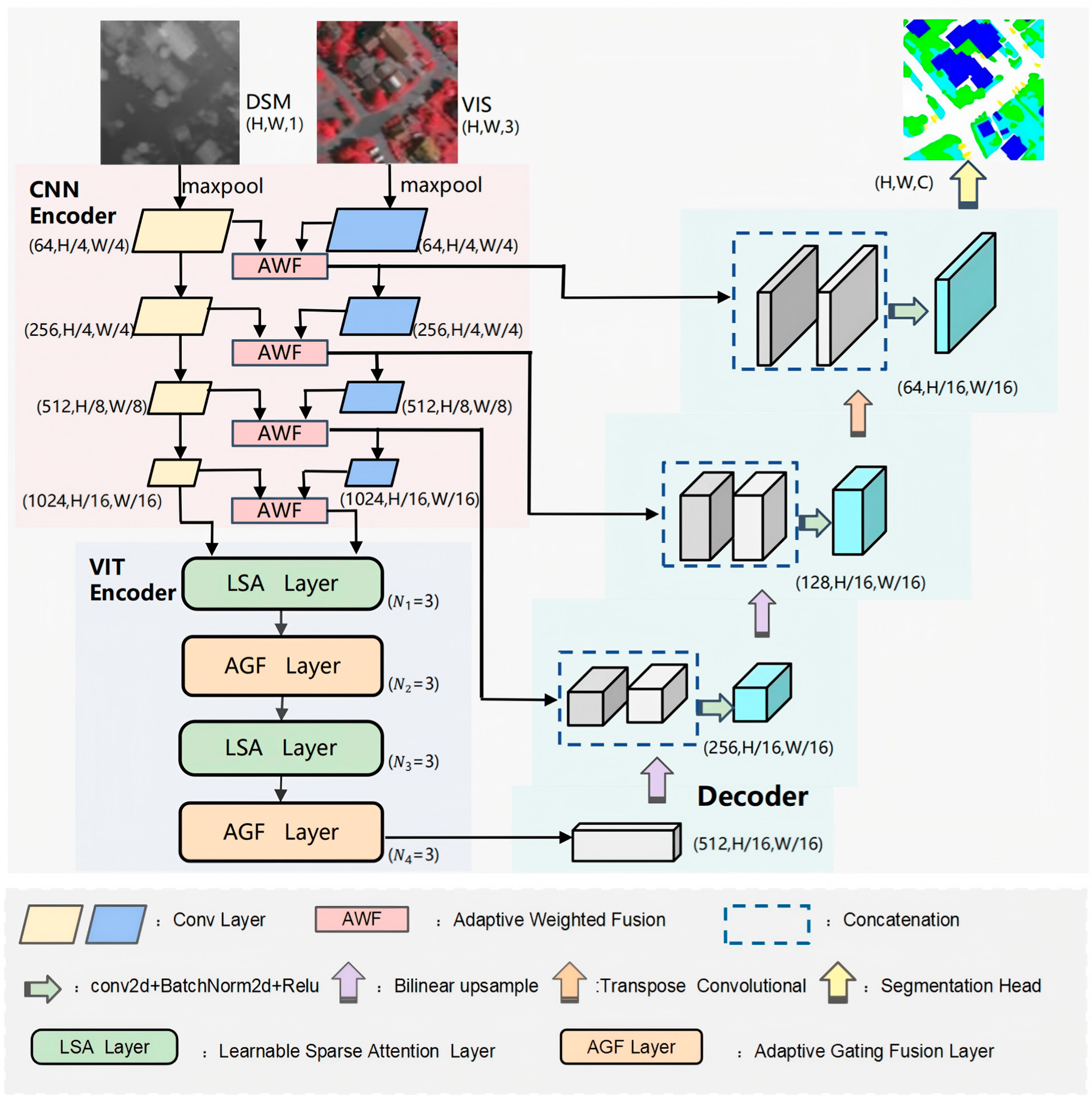

ASGT-Net: A Multi-Modal Semantic Segmentation Network with Symmetric Feature Fusion and Adaptive Sparse Gating

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

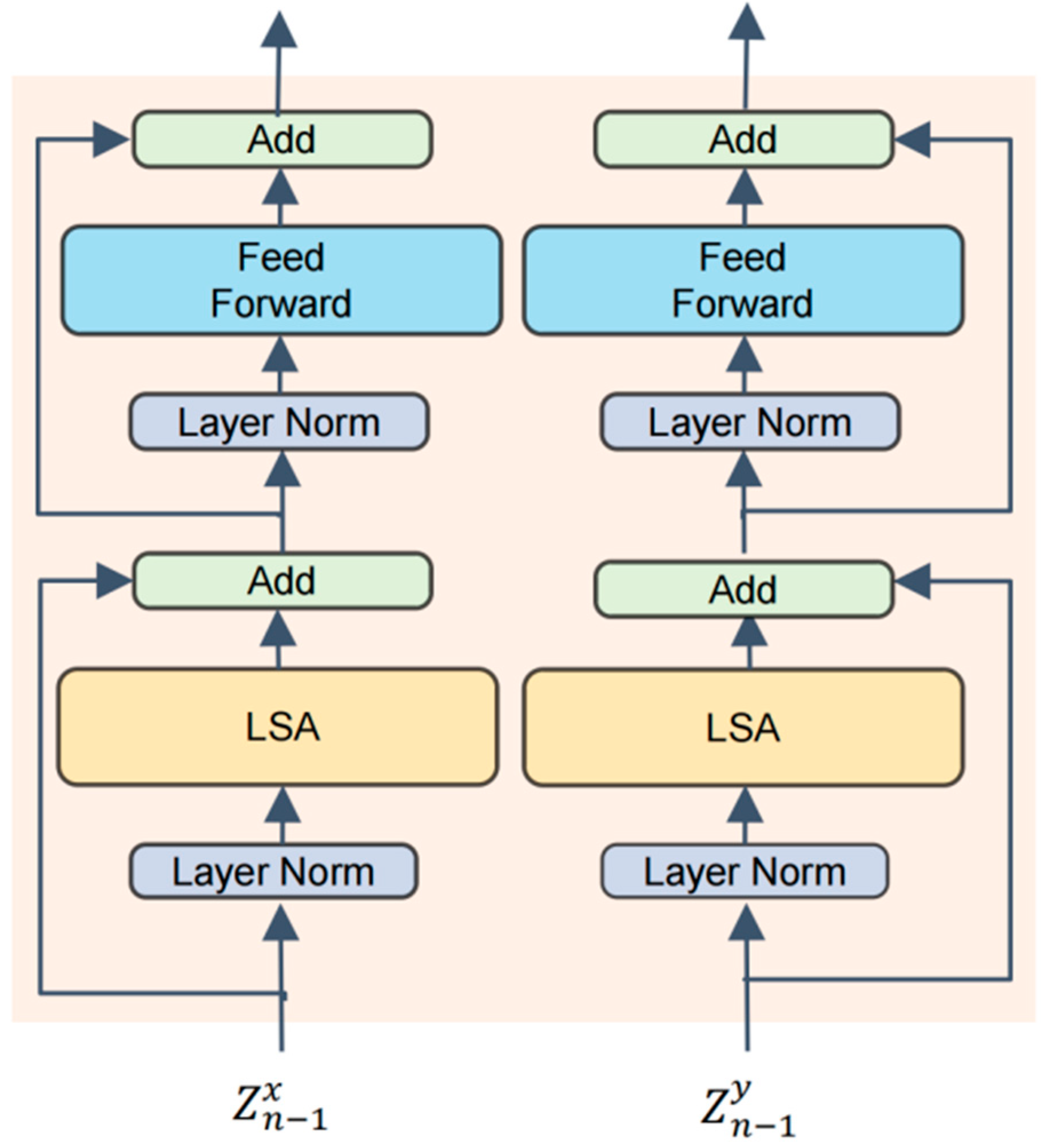

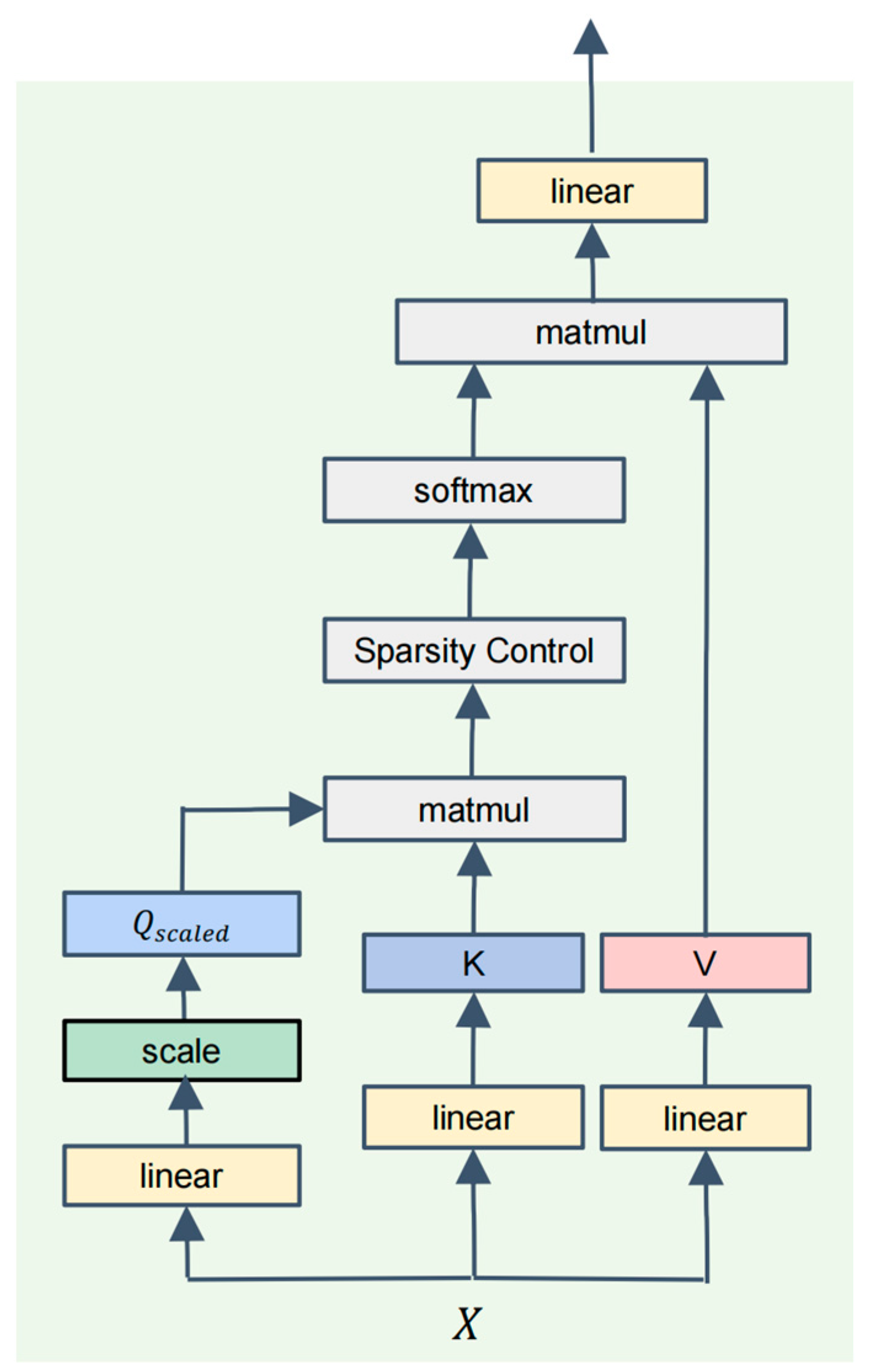

- This paper proposes an innovative multi-modal fusion network architecture that integrates ViT and CNN. In this fusion architecture, the ViT component incorporates a Learnable Sparse Attention (LSA) module, replacing the traditional self-attention mechanism, which significantly reduces computational complexity. This design allows ASGT-Net to effectively lower the computational burden while retaining the powerful feature extraction capabilities of Transformers.

- (2)

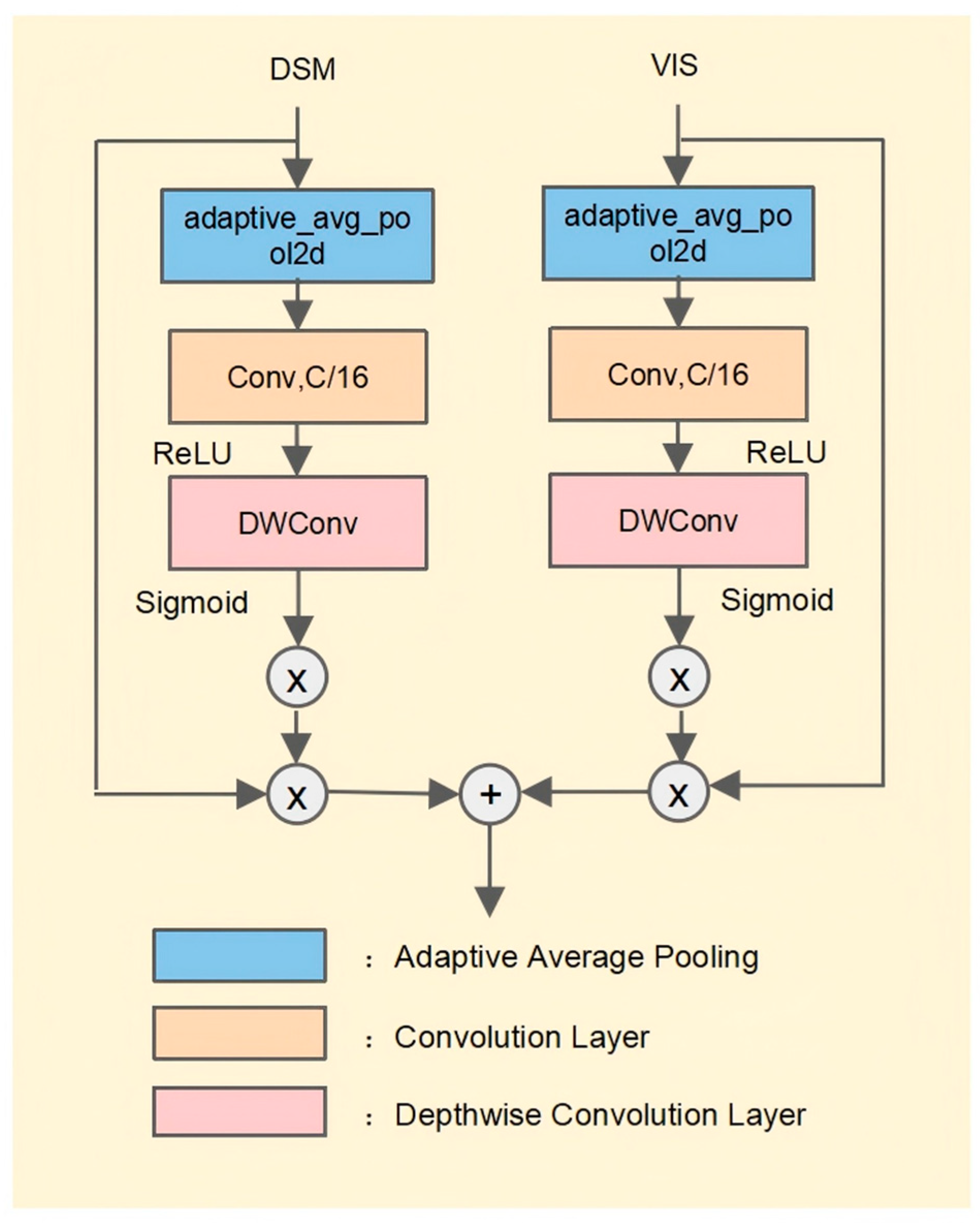

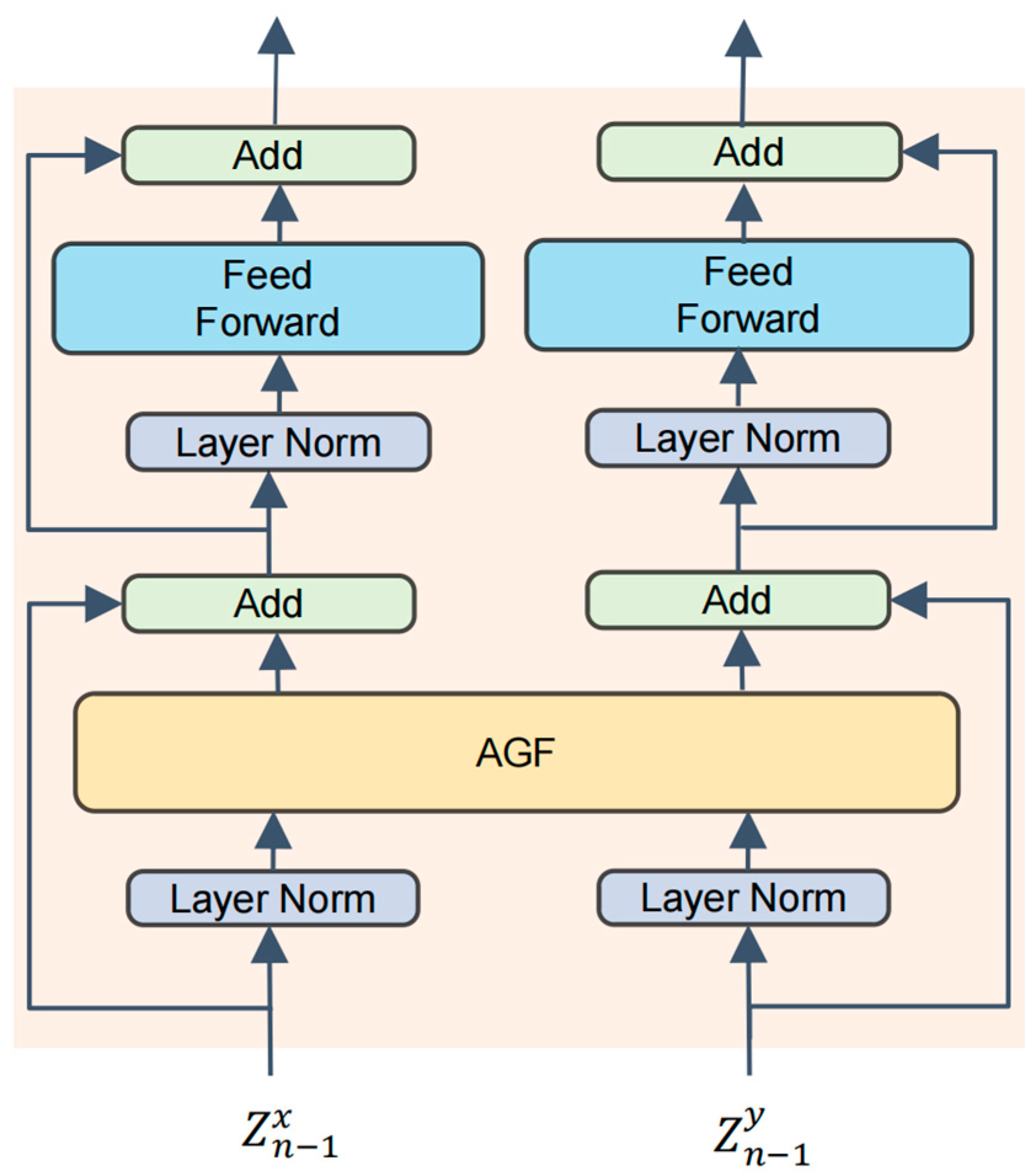

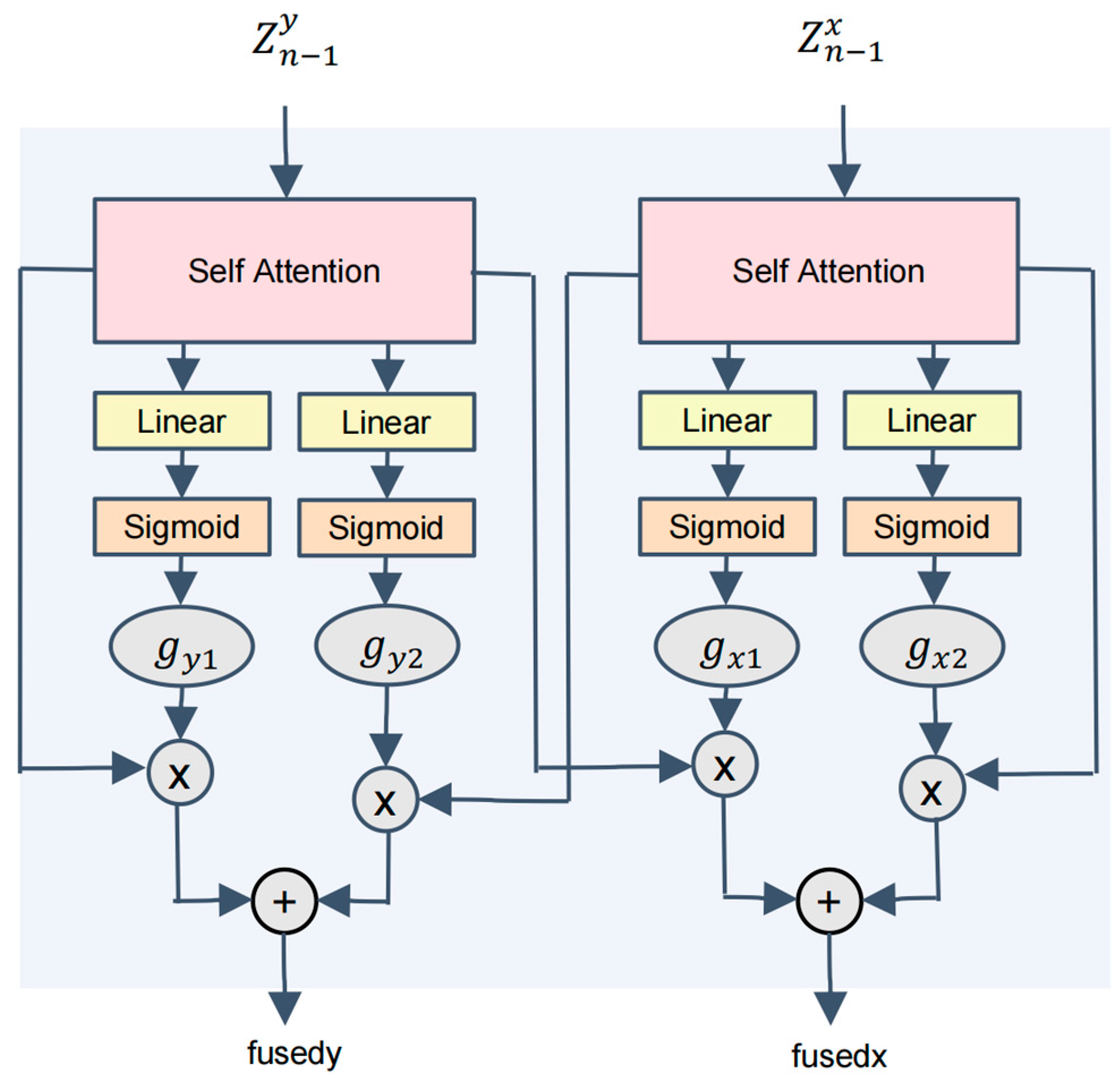

- During feature fusion, the CNN part employs an Adaptive Weighted Fusion (AWF) module, which dynamically adjusts feature weights based on different modalities to emphasize key information and enhance fusion effectiveness. Simultaneously, the ViT module integrates an Adaptive Gating Fusion (AGF) mechanism that alternates with the LSA module, optimizing inter-modal information exchange and facilitating effective integration of global and local features.

- (3)

- Through rigorous comparative experiments on the ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets, results demonstrate that ASGT-Net significantly improves segmentation performance while maintaining low computational complexity, outperforming other state-of-the-art multi-modal fusion methods. These experiments validate ASGT-Net’s superiority in efficiently fusing multi-modal data, enhancing accuracy, and improving computational efficiency.

2. Related Works

2.1. Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Imagery

2.2. Semantic Segmentation with CNN–Transformer Architectures

2.3. Multi-Source Data Fusion for Semantic Segmentation

3. Math

3.1. Feature Representation and Preliminary Fusion Coding Module

3.2. Deep Feature Processing and Fusion Coding Module

| Algorithm 1: LSA Module with Top-K Sparsification |

| Input: feature sequence , number of attention heads , learnable sparsity parameter Output: output features

|

3.3. Decoding and Feature Reconstruction Module

4. Experiments and Discussions

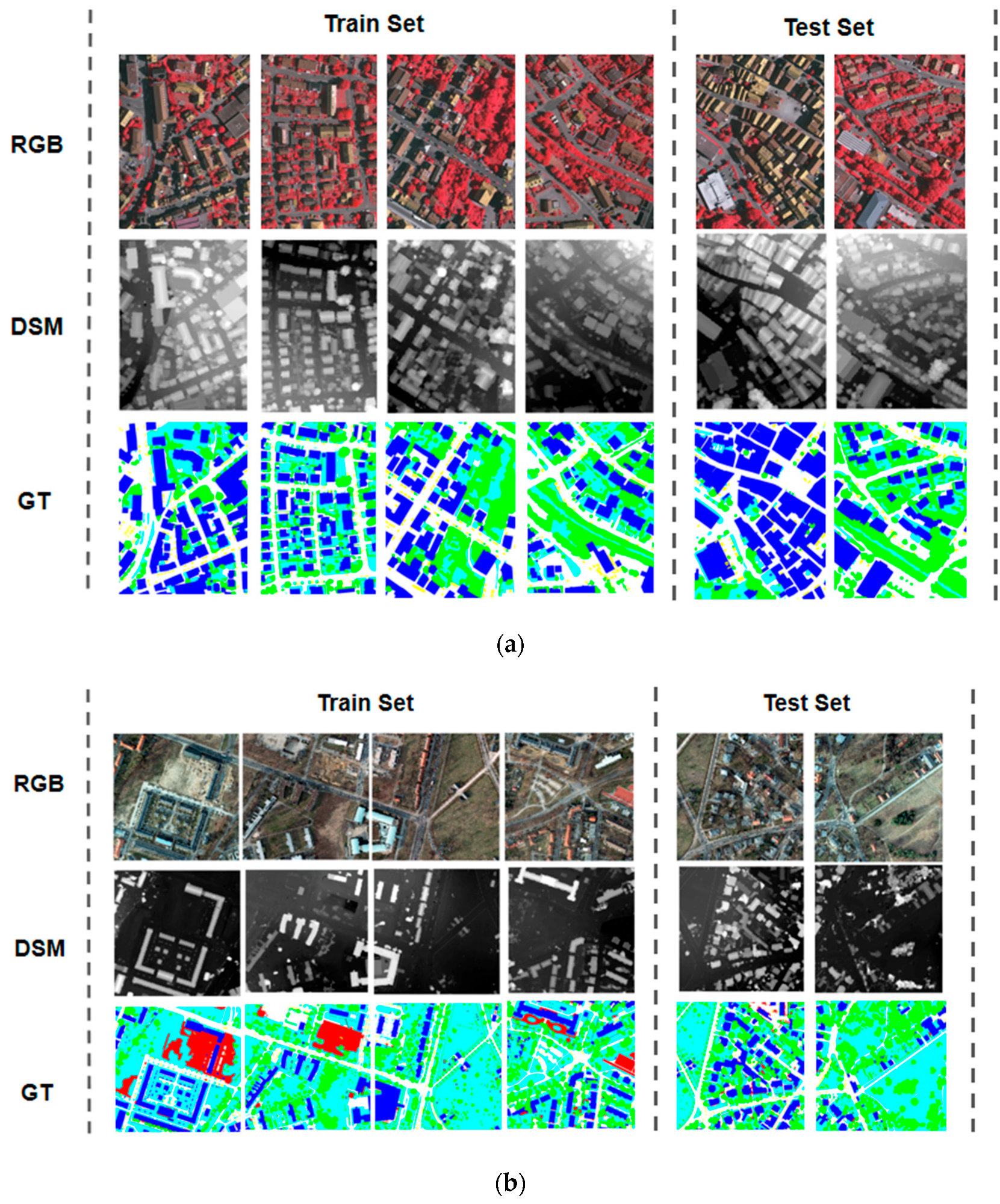

4.1. Datasets and Initial Preparation

4.2. Assessment of Indicators

4.3. Implementation Details

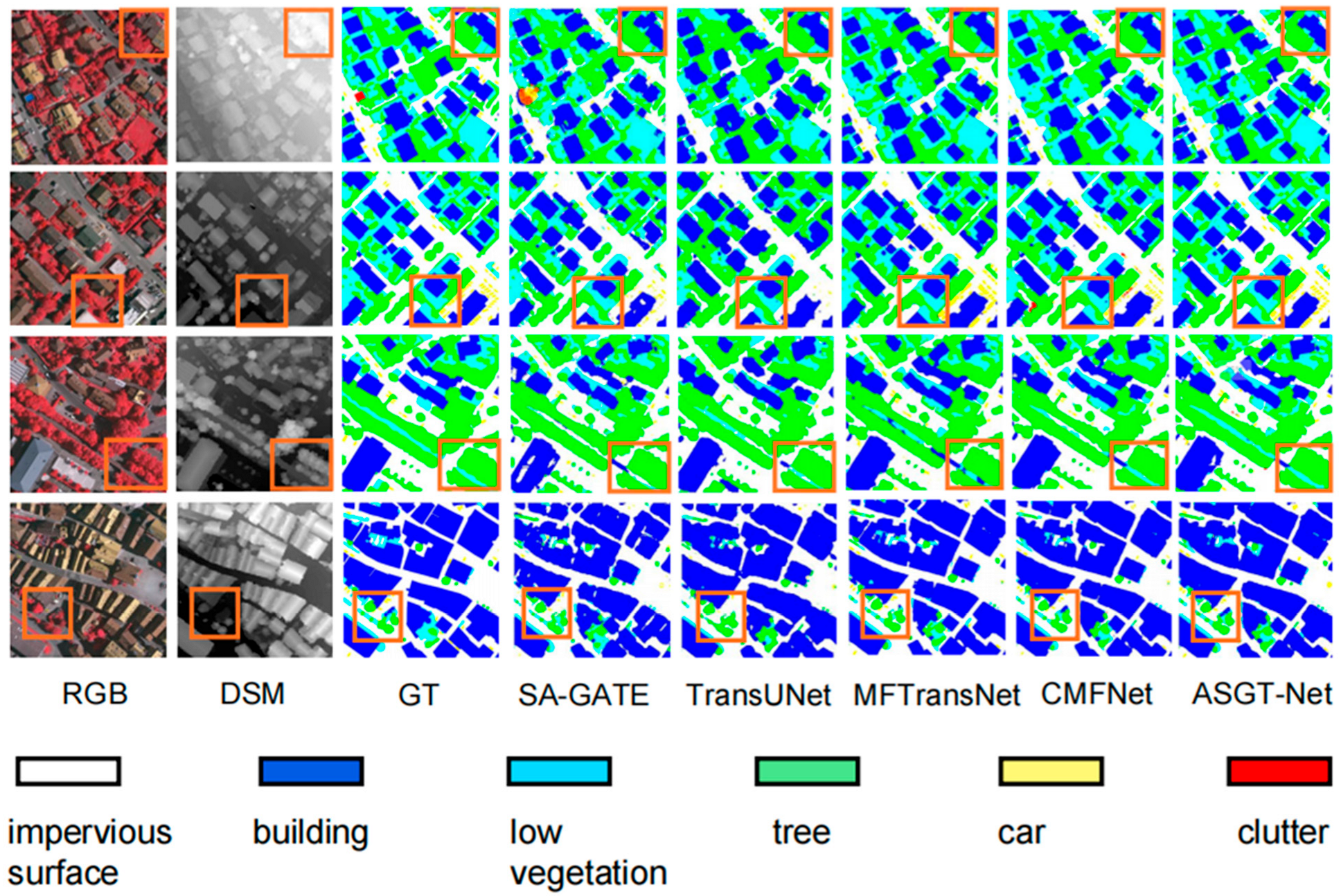

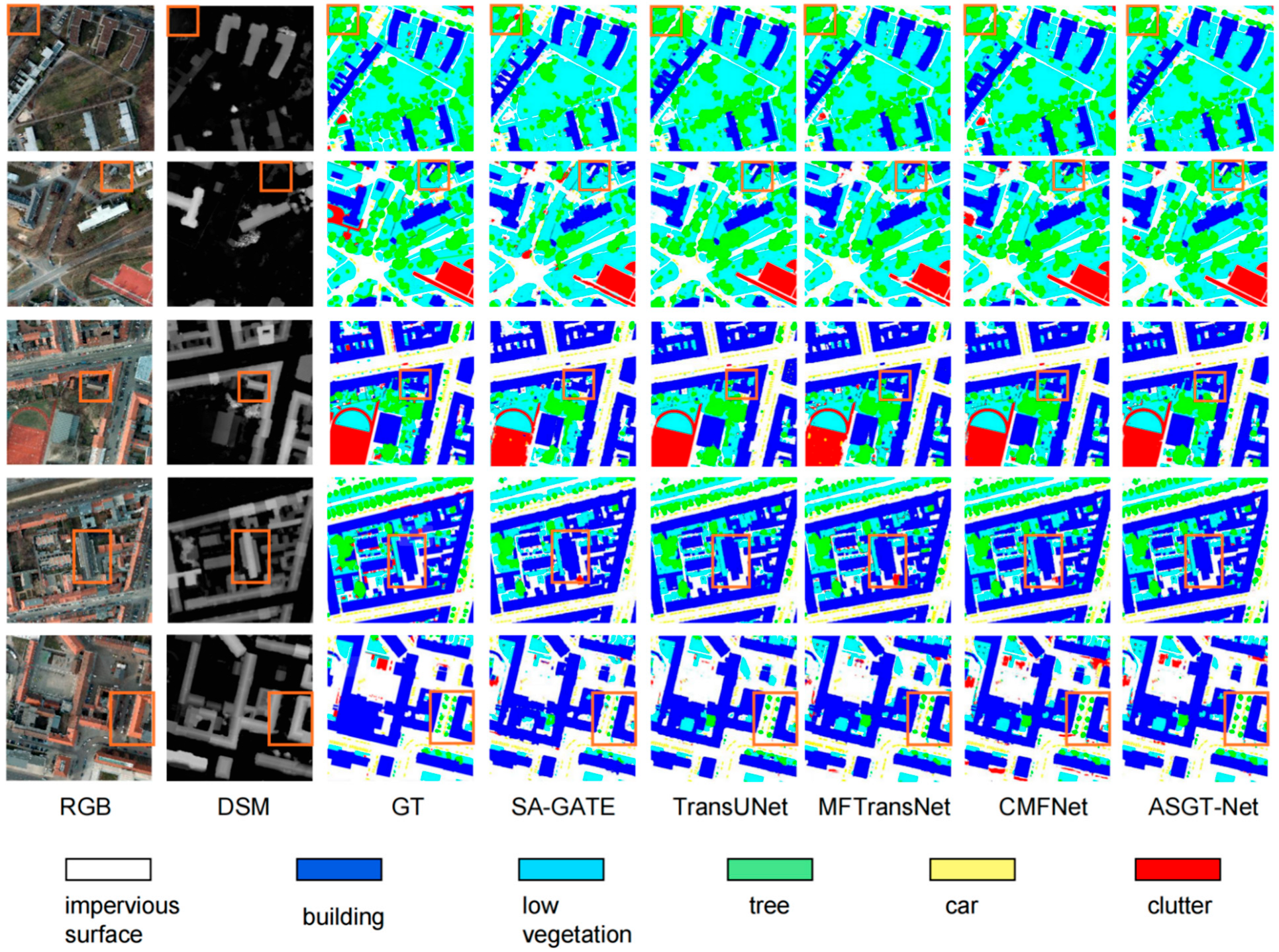

4.4. Comparative Experiments

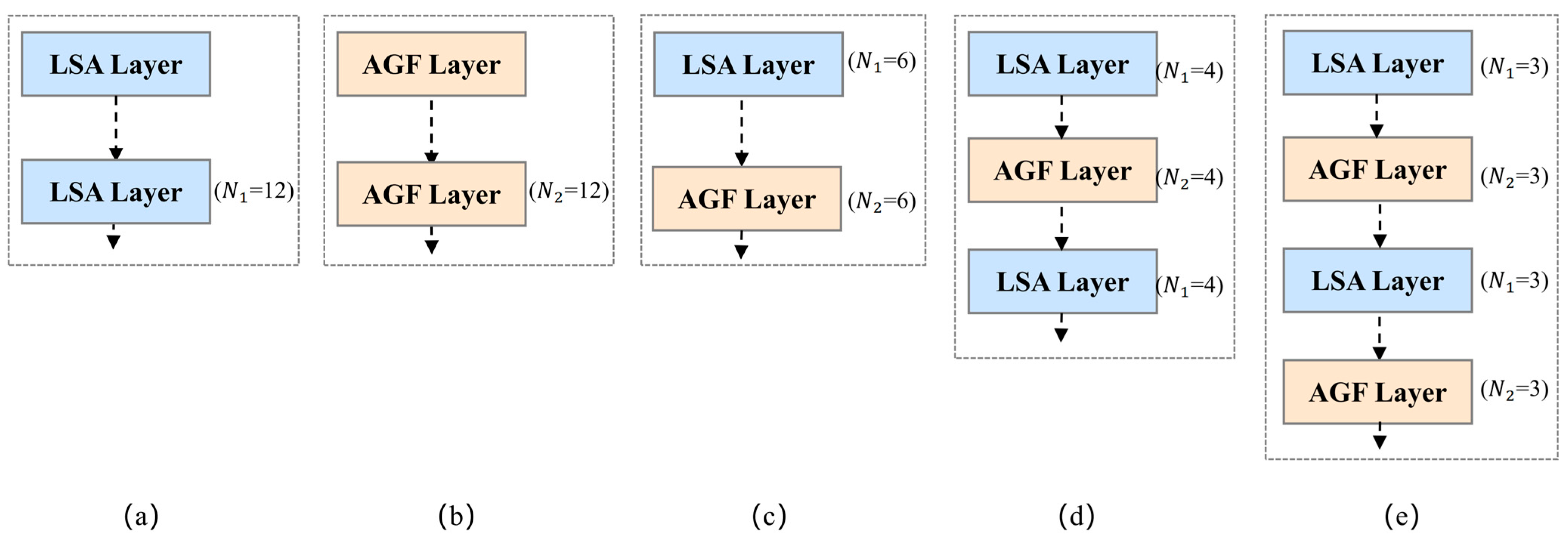

4.5. Ablation Experiment

4.6. Computational Complexity Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richards, J.A.; Richards, J.A. Remote Sensing Digital Image Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.C.; Bakon, M.; Lopes, D.; Cunha, A.; Sousa, J.J. A systematic review on soil moisture estimation using remote sensing data for agricultural applications. Sci. Remote Sens. 2025, 12, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Xia, J.S.; Xue, Z.H.; Tan, K.; Su, H.; Bao, R. Review of hyperspectral remote sensing image classification. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 20, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Deng, C.; Su, Y.; An, Z.; Wang, Q. Methods and datasets on semantic segmentation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle remote sensing images: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 211, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.M.; Liu, W.; Zang, Y.; Afzal, M.K.; Bello, S.A.; Muhammad, A.U.; Wang, C.; Li, J. Deep learning-based semantic segmentation of urban-scale 3D meshes in remote sensing: A survey. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 121, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Chen, C.; Zhang, D.; Sang, Y.; Zhang, L. Semantic segmentation of deep learning remote sensing images based on band combination principle: Application in urban planning and land use. Comput. Commun. 2024, 217, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C. Classification of rice varieties using hyperspectral imaging with multi-dimensional fusion convolutional neural networks. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 148, 108389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, G.; Johnson, B.A. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Syam, M.S.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Keung, L.W.; Zeeshan, Z.; Ali, Y.A.; Sarhan, N. Utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNN) and U-Net architecture for precise crop and weed segmentation in agricultural imagery: A deep learning approach. Big Data Res. 2024, 36, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Shin, J.; Kim, H. VFF-Net: Evolving forward–forward algorithms into convolutional neural networks for enhanced computational insights. Neural Netw. 2025, 190, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulgalil, H.D.; Basir, O.A. Next-generation image captioning: A survey of methodologies and emerging challenges from transformers to Multimodal Large Language Models. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2025, 12, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, R.; Kotei, E. A comprehensive review on transformer network for natural and medical image analysis. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 53, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, N.; You, Z. Combining feature compensation and GCN-based reconstruction for multimodal remote sensing image semantic segmentation. Inf. Fusion 2025, 122, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Qian, Y.; Gong, W.; Chu, Z.; Qin, Y.; Muhetaer, P. Multi-level interactive fusion network based on adversarial learning for fusion classification of hyperspectral and LiDAR data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 125132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Liu, H.; Duan, P.; Wei, X.; Li, S. Feature-based multimodal remote sensing image matching: Benchmark and state-of-the-art. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 229, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. Deep learning in multimodal remote sensing data fusion: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Mura, M.; Prasad, S.; Pacifici, F.; Gamba, P.; Chanussot, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Challenges and opportunities of multimodality and data fusion in remote sensing. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 1585–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Hussain, M.; Albashrawi, M.A.; Bendechache, M.; Owais, M. A comprehensive review of techniques, algorithms, advancements, challenges, and clinical applications of multi-modal medical image fusion for improved diagnosis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 272, 109014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. S2DBFT: Spectral-Spatial Dual-Branch Fusion Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5525517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleissaee, A.A.; Kumar, A.; Anwer, R.M.; Khan, S.; Cholakkal, H.; Xia, G.-S.; Khan, F.S. Transformers in remote sensing: A survey. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ma, L.; He, G.; Johnson, B.A.; Yan, Z.; Chang, M.; Liang, Y. Transformers for Remote Sensing: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, T.; Lin, F.; Tian, S.; Guo, G. Fully transformer networks for semantic image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.04108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibola, S.; Cabral, P. A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Semantic Segmentation Models in Land Cover Mapping. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Proceedings, Part III 18. pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.; Hong, S.; Han, B. Learning deconvolution network for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1520–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 6881–6890. [Google Scholar]

- Strudel, R.; Garcia, R.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C. Segmenter: Transformer for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 7262–7272. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Zeng, K. Remote Sensing Image Information Granulation Transformer for Semantic Segmentation. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 84, 1485–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Xue, D.; Chi, W.; Luan, J.; Liu, J. CSFAFormer: Category-selective feature aggregation transformer for multimodal remote sensing image semantic segmentation. Inf. Fusion 2025, 127, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, P.; Ji, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, X. A Transformer-based multi-modal fusion network for semantic segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 133, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Online, 6–14 December 2021; Article 924. [Google Scholar]

- Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I. Generating Long Sequences with Sparse Transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.10509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, M.; Guruganesh, G.; Dubey, K.A.; Ainslie, J.; Alberti, C.; Ontanon, S.; Pham, P.; Ravula, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L. Big bird: Transformers for longer sequences. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17283–17297. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Fu, R.; Huang, L.; Lin, W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Hrformer: High-resolution transformer for dense prediction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.09408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: Redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranftl, R.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Koltun, V. Vision transformers for dense prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 12179–12188. [Google Scholar]

- Valada, A.; Oliveira, G.L.; Brox, T.; Burgard, W. Deep multispectral semantic scene understanding of forested environments using multimodal fusion. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Experimental Robotics, Tokyo, Japan, 3–6 October 2016; pp. 465–477. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. Pointnet++: Deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Hazirbas, C.; Ma, L.; Domokos, C.; Cremers, D. Fusenet: Incorporating depth into semantic segmentation via fusion-based cnn architecture. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ACCV 2016: 13th Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 November 2016; Revised Selected Papers, Part I 13. pp. 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.K.; Deria, A.; Hong, D.; Rasti, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. Multimodal fusion transformer for remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5515620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valada, A.; Mohan, R.; Burgard, W. Self-supervised model adaptation for multimodal semantic segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 1239–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, Q.; Gui, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, W. Cross-Modal Segmentation Network for Winter Wheat Mapping in Complex Terrain Using Remote-Sensing Multi-Temporal Images and DEM Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Ming, Z.; Feng, W.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Zhao, K. MMFormer: Multimodal Transformer Using Multiscale Self-Attention for Remote Sensing Image Classification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtehaz, N.; Rahman, M.S. MultiResUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Jasch, M.; Fröhlich, B.; Weber, T.; Franke, U.; Pollefeys, M.; Rätsch, M. Multimodal neural networks: RGB-D for semantic segmentation and object detection. In Proceedings of the Image Analysis: 20th Scandinavian Conference, SCIA 2017, Tromsø, Norway, 12–14 June 2017; Proceedings, Part I 20. pp. 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Zhao, C.; Shao, H.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y. TMFF: Trustworthy multi-focus fusion framework for multi-label sewer defect classification in sewer inspection videos. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 12274–12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Jin, X. Gated attention fusion network for multimodal sentiment classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 240, 108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.; Solorio, T.; Montes-y-Gomez, M.; González, F.A. Gated multimodal networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 10209–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Multi-modal gated mixture of local-to-global experts for dynamic image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 23555–23564. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Koh, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, J.; Hwang, Y.; Choi, J.W. Robust deep multi-modal learning based on gated information fusion network. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Perth, Australia, 2–6 December 2018; pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Lin, K.-Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Qian, C.; Li, H.; Zeng, G. Bi-directional cross-modality feature propagation with separation-and-aggregation gate for RGB-D semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 561–577. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; He, Y.; Du, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. YCANet: Target detection for complex traffic scenes based on camera-LiDAR fusion. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 8379–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhi, H.; Gao, E.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, X. DeepU-Net: A Parallel Dual-Branch Model for Deeply Fusing Multi-Scale Features for Road Extraction from High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 9448–9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, P.M. ABCNet: Attentive bilateral contextual network for efficient semantic segmentation of Fine-Resolution remotely sensed imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 181, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Audebert, N.; Le Saux, B.; Lefèvre, S. Beyond RGB: Very high resolution urban remote sensing with multimodal deep networks. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 140, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seichter, D.; Köhler, M.; Lewandowski, B.; Wengefeld, T.; Gross, H.-M. Efficient rgb-d semantic segmentation for indoor scene analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 13525–13531. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpour, H.; Samadzadegan, F.; Javan, F.D. CMGFNet: A deep cross-modal gated fusion network for building extraction from very high-resolution remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 184, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.-O. A crossmodal multiscale fusion network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 3463–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. MFTransNet: A multi-modal fusion with CNN-transformer network for semantic segmentation of HSR remote sensing images. Mathematics 2023, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 10 |

| Epochs | 50 |

| Optimizer | SGD |

| Initial learning rate | 0.01 |

| Momentum | 0.9 |

| Weight decay | 0.0005 |

| LR scheduler | MultiStepLR |

| LR decay milestones | [25, 35, 45] |

| LR decay factor γ | 0.1 |

| Loss function | Weighted Cross-Entropy |

| Sparsity learning rate | 0.001 |

| Sparsity LR scheduler | MultiStepLR (same milestones) |

| L1 regularization λ | 1 × 10−4 |

| Early stopping patience | 7 |

| Early stopping min delta | 0.001 |

| Random seed | 42 |

| Method | OA(%) | mF1 (%) | mIoU (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impervious Surfaces | Building | Low Vegetation | Tree | Car | Total | |||

| ABCNet (2021) [62] (ABCNet—https://github.com/lironui/ABCNet (commit: 3067b46; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 94.10 | 90.81 | 78.53 | 64.12 | 89.70 | 89.25 | 85.34 | 75.20 |

| PSPNet (2017) [63] (PSPNet—https://github.com/hszhao/PSPNet (commit: 798bdc9; accessed on 26 October 2025) | 94.52 | 90.17 | 78.84 | 79.22 | 92.03 | 89.94 | 86.55 | 76.96 |

| FuseNet (2016) [45] (FuseNet—https://github.com/xmindflow/FuseNet (commit: e8ec1b4; accessed on 26 October 2025) | 96.28 | 90.28 | 78.98 | 81.37 | 91.66 | 90.51 | 87.71 | 78.71 |

| vFuseNet (2018) [64] | 95.92 | 91.36 | 77.64 | 76.06 | 91.85 | 90.49 | 87.89 | 78.92 |

| ESANet (2021) [65] (ESANet—https://github.com/TUI-NICR/ESANet (commit: 49d2201; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 95.69 | 90.50 | 77.16 | 85.46 | 91.39 | 90.61 | 88.18 | 79.42 |

| CMGFNet (2022) [66] (CMGFNet—https://github.com/hamidreza2015/CMGFNet-Building_Extraction (commit: e0ce252; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 97.75 | 91.60 | 80.03 | 87.28 | 92.35 | 91.72 | 90.00 | 82.26 |

| SA-GATE (2020) [59] (SA-GATE—https://github.com/charlesCXK/RGBD_Semantic_Segmentation_PyTorch (commit: 32b3f86; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 91.69 | 94.84 | 81.29 | 92.56 | 87.79 | 91.10 | 89.81 | 81.27 |

| TransUNet (2021) [67] (TransUNet—https://github.com/Beckschen/TransUNet (commit: 192e441; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 91.66 | 96.48 | 76.14 | 92.77 | 69.56 | 90.96 | 87.34 | 78.26 |

| UNetFormer (2022) [68] (UNetFormer—https://github.com/WangLibo1995/GeoSeg (commit: 9453fe4; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 97.69 | 86.47 | 87.93 | 95.91 | 92.27 | 90.65 | 89.85 | 81.97 |

| CMFNet (2022) [69] (CMFNet—https://github.com/FanChiMao/CMFNet (commit: 84a05e1; accessed on 26 October 2025)) | 92.36 | 97.17 | 80.37 | 90.82 | 85.47 | 91.40 | 89.48 | 81.44 |

| MFTransNet (2023) [70] | 92.11 | 96.41 | 80.09 | 91.48 | 86.52 | 91.22 | 89.62 | 81.61 |

| ASGT-Net | 92.48 | 97.76 | 82.18 | 91.73 | 90.33 | 92.30 | 90.88 | 83.65 |

| Method | OA(%) | mF1 (%) | mIoU (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impervious Surfaces | Building | Low Vegetation | Tree | Car | Total | |||

| ABCNet (2021) [62] | 88.90 | 96.23 | 86.40 | 78.92 | 92.92 | 87.52 | 88.14 | 79.26 |

| PSPNet (2017) [63] | 90.91 | 97.03 | 85.67 | 83.13 | 88.81 | 88.67 | 88.92 | 80.36 |

| FuseNet (2016) [45] | 92.64 | 97.48 | 87.31 | 85.14 | 96.10 | 90.58 | 91.60 | 84.86 |

| vFuseNet (2018) [64] | 91.62 | 91.36 | 89.03 | 84.29 | 95.49 | 90.22 | 87.89 | 78.92 |

| ESANet (2021) [65] | 92.76 | 97.10 | 87.81 | 85.31 | 94.08 | 90.61 | 88.18 | 79.42 |

| CMGFNet (2022) [66] | 92.60 | 97.41 | 86.68 | 86.80 | 95.68 | 89.74 | 91.40 | 84.53 |

| SA-GATE (2020) [59] | 90.77 | 96.54 | 85.35 | 81.18 | 96.63 | 87.91 | 90.26 | 82.53 |

| TransUNet (2021) [67] | 91.93 | 96.63 | 89.98 | 82.65 | 93.17 | 90.01 | 90.97 | 83.74 |

| UNetFormer (2022) [68] | 92.27 | 97.69 | 87.93 | 95.91 | 95.91 | 90.65 | 91.71 | 85.05 |

| CMFNet (2022) [69] | 92.84 | 97.63 | 88.00 | 86.47 | 95.68 | 91.16 | 92.10 | 85.63 |

| MFTransNet (2023) [70] | 92.45 | 97.37 | 86.92 | 85.71 | 96.05 | 89.96 | 91.11 | 84.04 |

| ASGT-Net | 92.89 | 98.24 | 89.20 | 91.36 | 94.02 | 91.24 | 92.30 | 86.10 |

| Dataset | Seed | OA(%) | mF1 (%) | mIoU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaihingen | 42 | 91.34 | 92.51 | 86.32 |

| Vaihingen | 3407 | 91.27 | 92.48 | 86.10 |

| Vaihingen | 2025 | 91.41 | 92.49 | 86.25 |

| Vaihingen (Mean ± Std) | — | 91.34 ± 0.07 | 92.49 ± 0.02 | 86.22 ± 0.09 |

| Potsdam | 42 | 91.28 | 92.33 | 86.12 |

| Potsdam | 3407 | 91.19 | 92.27 | 86.05 |

| Potsdam | 2025 | 91.25 | 92.30 | 86.14 |

| Potsdam (Mean ± Std) | — | 91.24 ± 0.04 | 92.30 ± 0.03 | 86.10 ± 0.04 |

| Method | AWF | AGF | OA(%) | mF1 (%) | mIoU (%) | Impervious Surfaces IoU (%) | Building IoU (%) | Low Vegetation IoU (%) | Tree IoU (%) | Car IoU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 90.96 | 87.34 | 78.26 | 82.0 | 85.5 | 77.2 | 76.3 | 74.5 | ||

| Ours | √ | 92.16 | 90.54 | 83.13 | 87.5 | 89.0 | 82.7 | 81.0 | 78.3 | |

| Ours | √ | 91.46 | 90.29 | 82.63 | 86.3 | 88.2 | 81.9 | 79.5 | 77.8 | |

| Ours | √ | √ | 92.30 | 90.88 | 83.65 | 88.0 | 89.3 | 83.2 | 81.5 | 78.8 |

| Structure | OA(%) | mF1 (%) | mIoU (%) | Impervious Surfaces IoU (%) | Building IoU (%) | Low Vegetation IoU (%) | Tree IoU (%) | Car IoU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | 90.37 | 88.89 | 80.46 | 81.8 | 85.0 | 76.5 | 75.8 | 73.5 |

| (b) | 89.75 | 88.82 | 80.19 | 86.5 | 88.2 | 82.0 | 80.5 | 77.0 |

| (c) | 91.54 | 89.87 | 82.02 | 85.8 | 87.5 | 81.2 | 78.8 | 76.5 |

| (d) | 91.77 | 90.09 | 82.43 | 87.5 | 88.7 | 82.8 | 80.5 | 77.8 |

| (e) | 92.30 | 90.88 | 83.65 | 88.0 | 89.5 | 83.5 | 81.5 | 78.5 |

| Top-K Ratio (k) | mIoU (%) |

|---|---|

| 10% | 82.75 |

| 20% | 83.65 |

| 30% | 83.02 |

| Method | Parameters (M) | GFLOPs(G) | mIoU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSPNet (2017) [63] | 46.72 | 49.03 | 76.96 |

| FuseNet (2016) [45] | 42.08 | 58.37 | 78.71 |

| vFuseNet (2018) [64] | 44.17 | 60.36 | 78.92 |

| SA-GATE (2020) [59] | 110.85 | 41.28 | 81.27 |

| CMFNet (2022) [69] | 123.63 | 78.25 | 81.44 |

| MFTransNet (2023) [70] | 130.50 | 55.60 | 82.10 |

| ASGT-Net | 150.39 | 48.87 | 83.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yue, W.; Chang, K.; Liu, X.; Tan, K.; Chen, W. ASGT-Net: A Multi-Modal Semantic Segmentation Network with Symmetric Feature Fusion and Adaptive Sparse Gating. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122070

Yue W, Chang K, Liu X, Tan K, Chen W. ASGT-Net: A Multi-Modal Semantic Segmentation Network with Symmetric Feature Fusion and Adaptive Sparse Gating. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122070

Chicago/Turabian StyleYue, Wendie, Kai Chang, Xinyu Liu, Kaijun Tan, and Wenqian Chen. 2025. "ASGT-Net: A Multi-Modal Semantic Segmentation Network with Symmetric Feature Fusion and Adaptive Sparse Gating" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122070

APA StyleYue, W., Chang, K., Liu, X., Tan, K., & Chen, W. (2025). ASGT-Net: A Multi-Modal Semantic Segmentation Network with Symmetric Feature Fusion and Adaptive Sparse Gating. Symmetry, 17(12), 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122070