UAVEdit-NeRFDiff: Controllable Region Editing for Large-Scale UAV Scenes Using Neural Radiance Fields and Diffusion Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

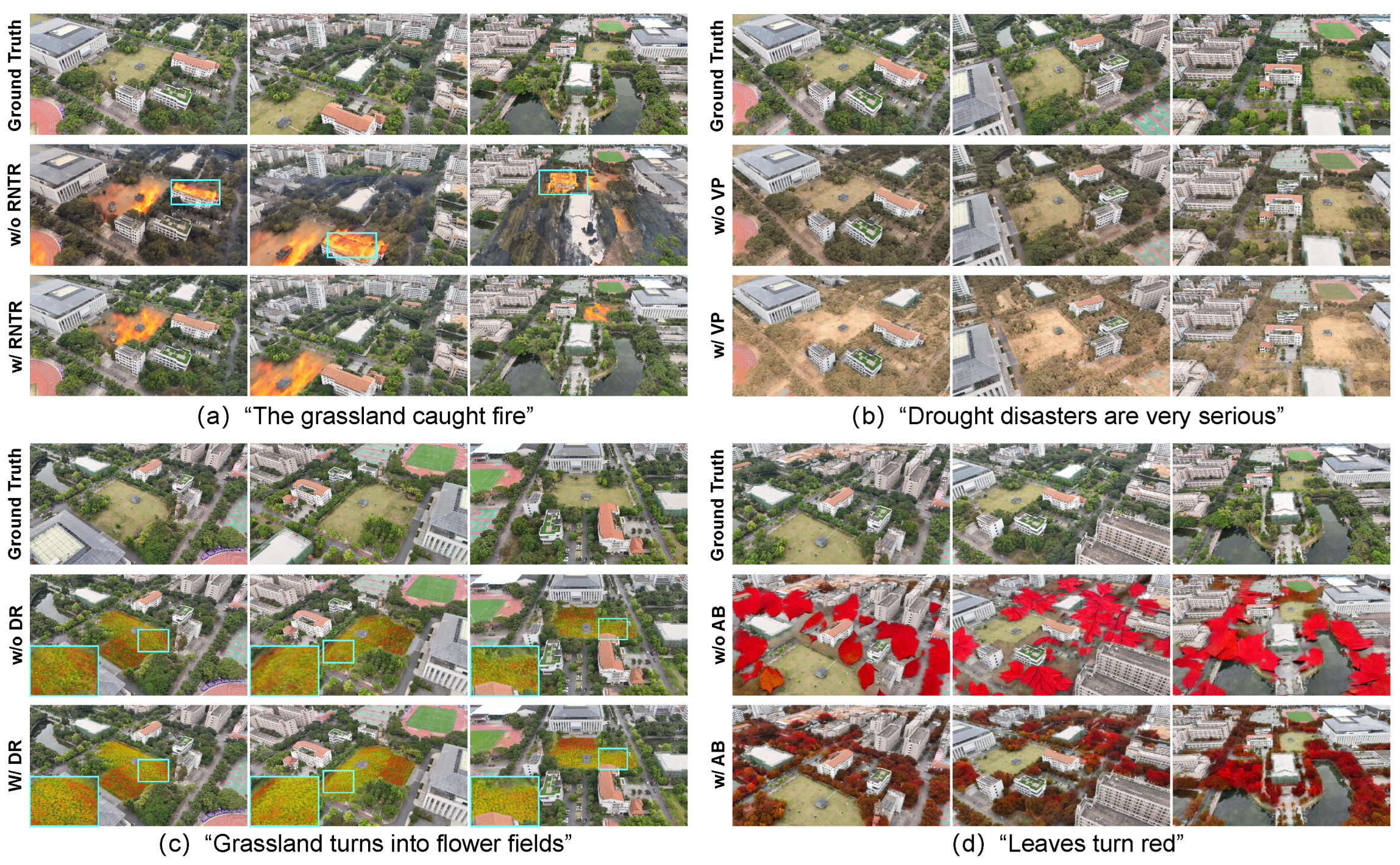

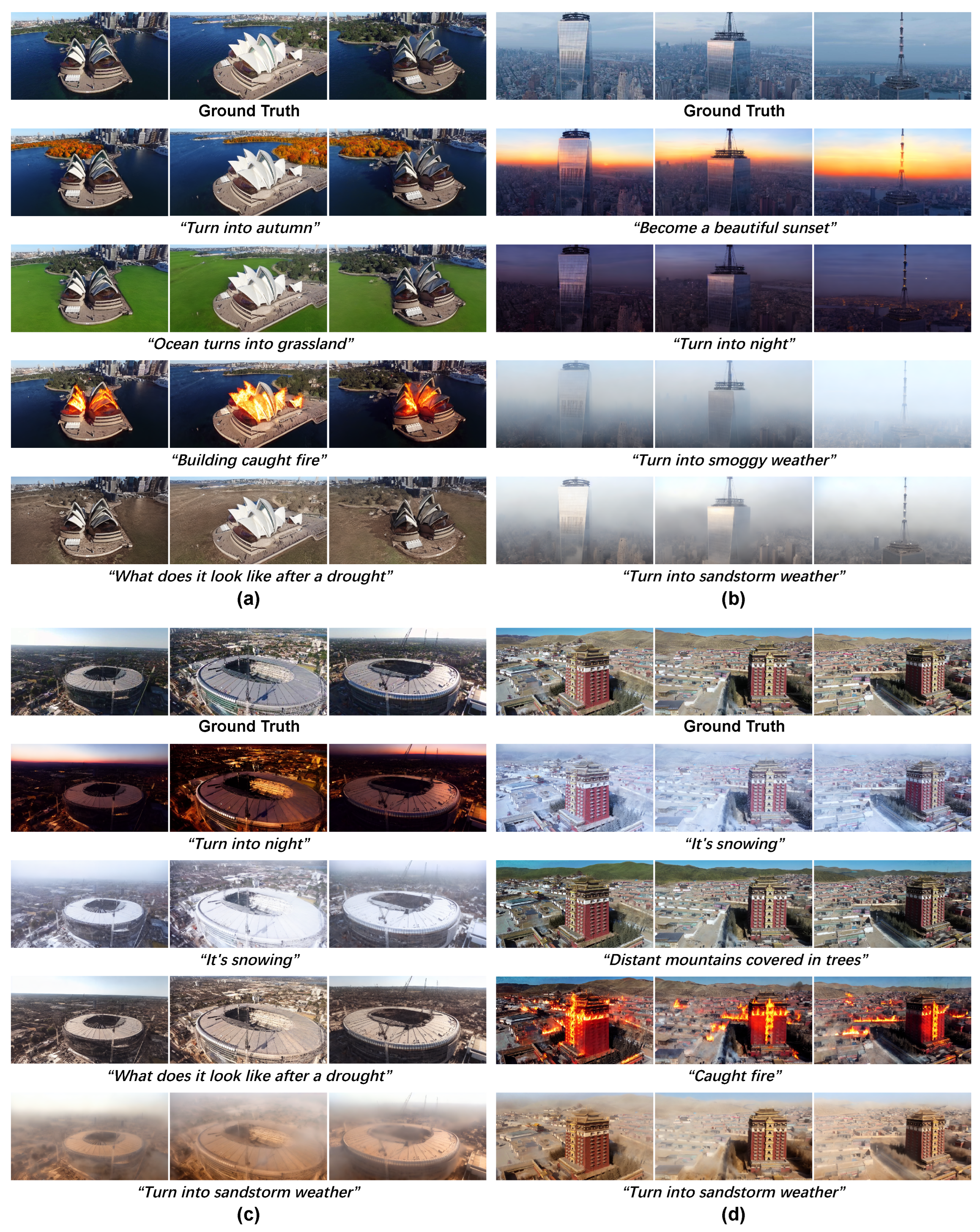

- Introducing visual-prior-guided local diffusion editing that leverages semantic masks to achieve object-level precision over edited regions while significantly enhancing semantic consistency.

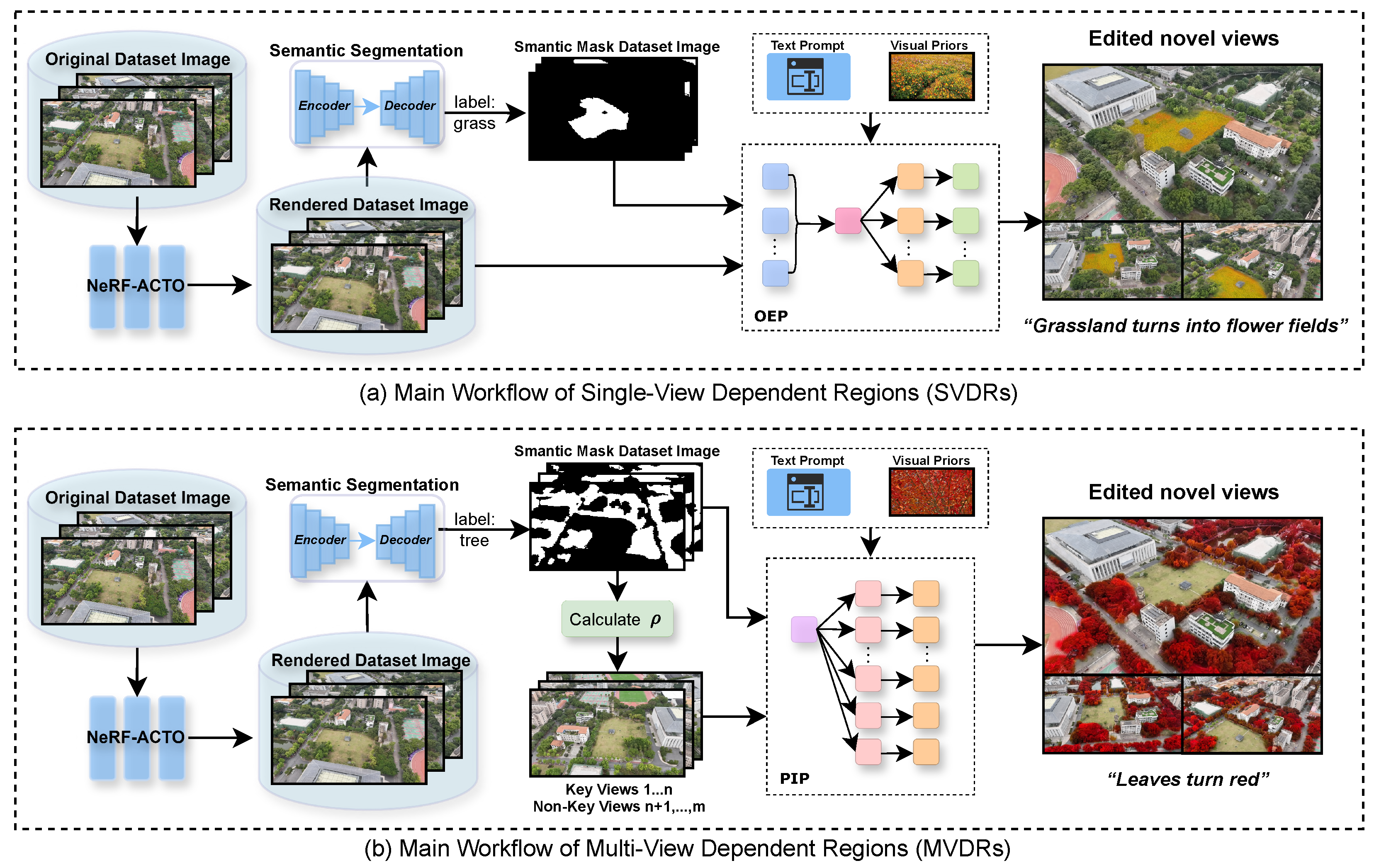

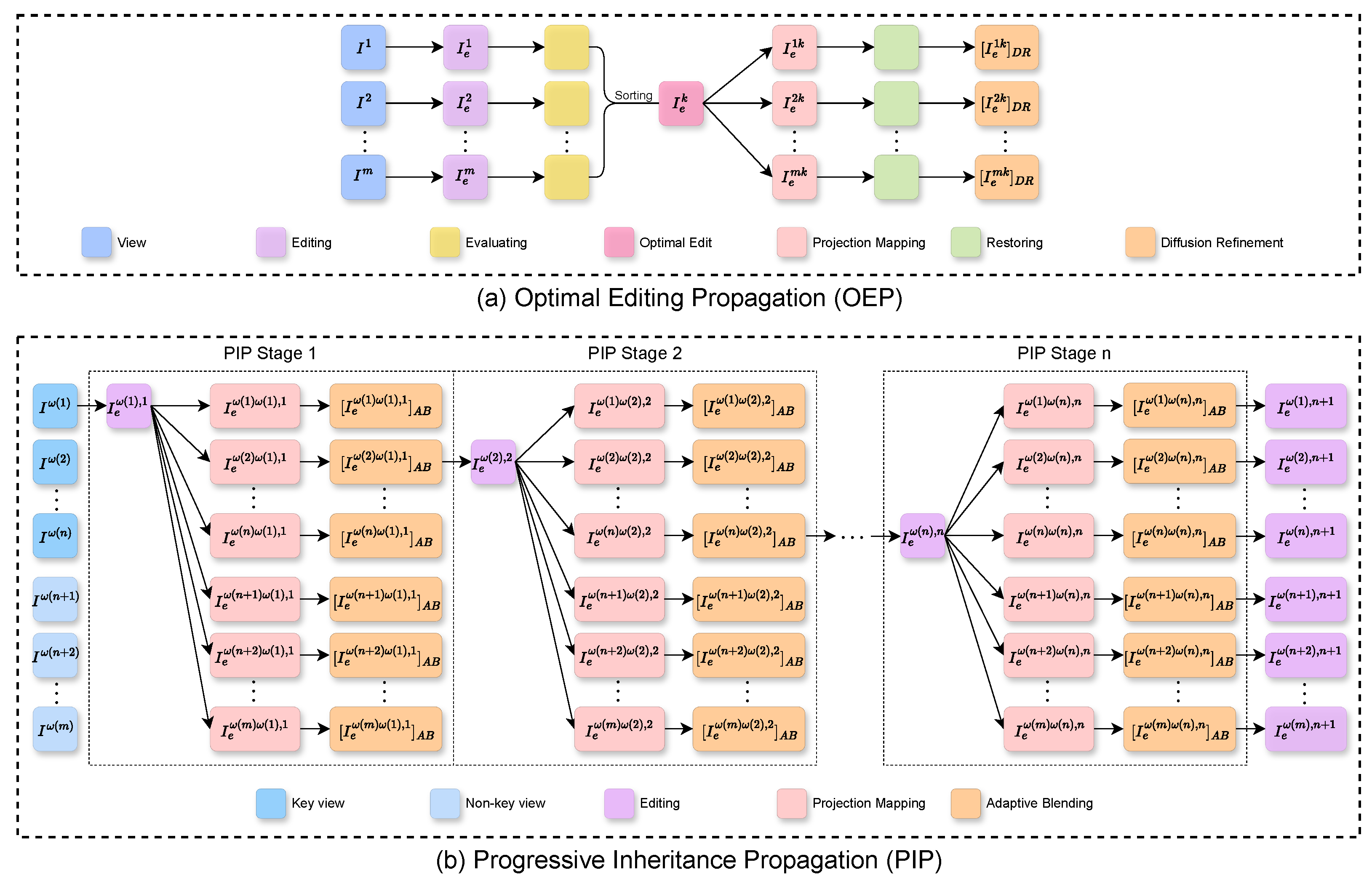

- An Optimal Editing Propagation (OEP) method is proposed based on TDB metrics to strengthen multi-view scene continuity for Single-View Dependent Regions (SVDRs) in UAV scenes. A subsequent Diffusion Refinement phase to further improve visual quality in target regions is included.

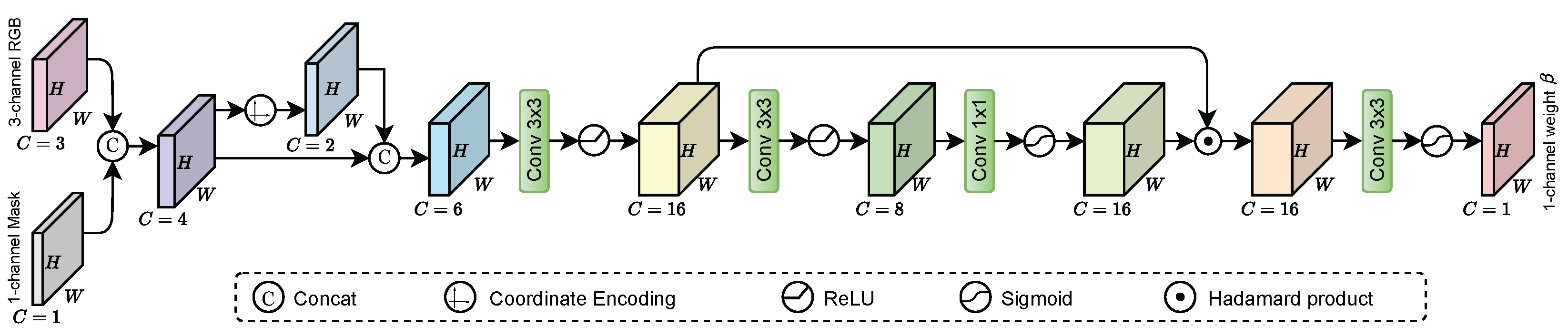

- A Progressive Inheritance Propagation (PIP) method is developed that employs Adaptive Blending to predict pixel-wise mixing weights, thereby balancing cross-view propagated edits with structural scene details and enhancing consistency in sparsely distributed Multi-View-Dependent Regions (MVDRs).

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Single-View Editing

2.3. Cross-View Propagation

2.3.1. Projection Mapping

2.3.2. Optimal Editing Propagation

2.3.3. Progressive Inheritance Propagation

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

3.2.1. Single-View Editing Evaluation Metrics

3.2.2. Image Quality Assessment Metrics

3.2.3. Comprehensive Evaluation Metrics

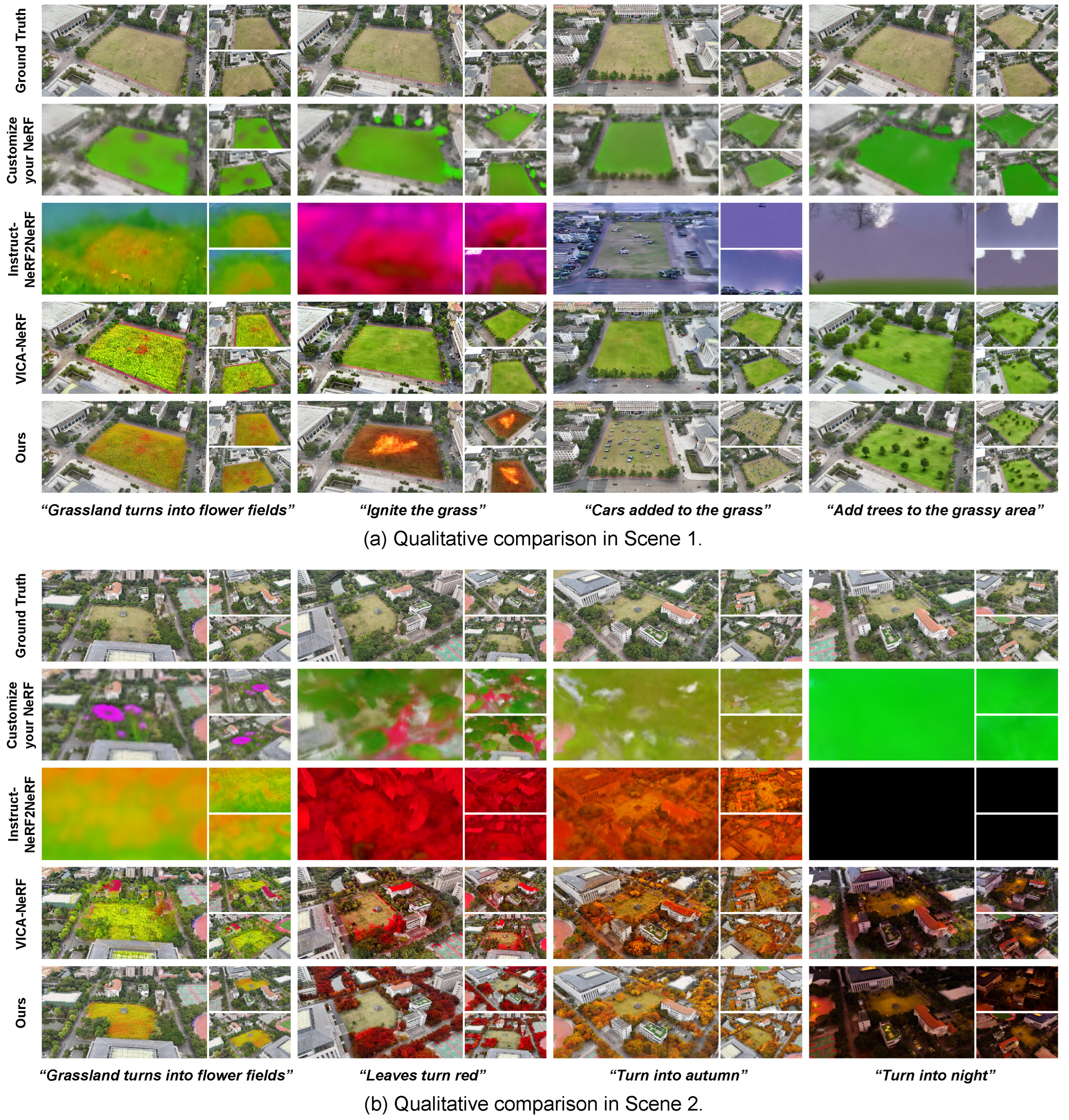

3.3. Comparative Experiments

3.4. Ablation Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, S.K.; Shukla, D.P. Application of drone for landslide mapping, dimension estimation and its 3D reconstruction. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2018, 46, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, G.; Cassidy, S.; Tian, N.; Shabana, M.E. Using Aerial Drone Photography to Construct 3D Models of Real World Objects in an Effort to Decrease Response Time and Repair Costs Following Natural Disasters. In Advances in Computer Vision, Proceedings of the 2019 Computer Vision Conference (CVC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–26 April 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, R.K.; Singh, Y.K. Study on characteristics and impact of Kalikhola landslide, Manipur, NE India, using UAV photogrammetry. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 6417–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, D.; Zuo, X.; Li, Q. UAV Image-Based 3D Reconstruction Technology in Landslide Disasters: A Review. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.; Karimi, E.; Rahnemoonfar, M. 3DAeroRelief: The first 3D Benchmark UAV Dataset for Post-Disaster Assessment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.11097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Yang, S.; Fahy, C.; Harwood, T.; Shell, J. Capturing the Past, Shaping the Future: A Scoping Review of Photogrammetry in Cultural Building Heritage. Electronics 2025, 14, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themistocleous, K. The Use of UAVs for Cultural Heritage and Archaeology. In Remote Sensing for Archaeology and Cultural Landscapes: Best Practices and Perspectives Across Europe and the Middle East; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Rao, Z.; Gao, W. Real-Time 3D Reconstruction for the Conservation of the Great Wall’s Cultural Heritage Using Depth Cameras. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Du, Q. From digital imagination to real-world exploration: A study on the influence factors of VR-based reconstruction of historical districts on tourists’ travel intention in the field. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokosza, A.; Wrede, H.; Esparza, D.G.; Makowski, M.; Liu, D.; Michels, D.L.; Pirk, S.; Palubicki, W. Scintilla: Simulating Combustible Vegetation for Wildfires. ACM Trans. Graph. 2024, 43, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Virtual Conference, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B.; Tancik, M.; Hedman, P.; Martin-Brualla, R.; Srinivasan, P.P. Mip-NeRF: A Multiscale Representation for Anti-Aliasing Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 5835–5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant neural graphics primitives with a multiresolution hash encoding. ACM Trans. Graph. 2022, 41, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Theobalt, C.; Komura, T.; Wang, W. NeuS: Learning Neural Implicit Surfaces by Volume Rendering for Multi-view Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual Conference, 6–14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 27171–27183. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Q.; Habermann, M.; Daniilidis, K.; Theobalt, C.; Liu, L. NeuS2: Fast Learning of Neural Implicit Surfaces for Multi-view Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 3272–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, M.; Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B.; Sajjadi, M.S.M.; Geiger, A.; Radwan, N. RegNeRF: Regularizing Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis from Sparse Inputs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 5470–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancik, M.; Casser, V.; Yan, X.; Pradhan, S.; Mildenhall, B.P.; Srinivasan, P.; Barron, J.T.; Kretzschmar, H. Block-NeRF: Scalable Large Scene Neural View Synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8238–8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turki, H.; Ramanan, D.; Satyanarayanan, M. Mega-NeRF: Scalable Construction of Large-Scale NeRFs for Virtual Fly- Throughs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 12912–12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiangli, Y.; Xu, L.; Pan, X.; Zhao, N.; Rao, A.; Theobalt, C.; Dai, B.; Lin, D. BungeeNeRF: Progressive Neural Radiance Field for Extreme Multi-scale Scene Rendering. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Volume 13692, pp. 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xiangli, Y.; Peng, S.; Pan, X.; Zhao, N.; Theobalt, C.; Dai, B.; Lin, D. Grid-guided Neural Radiance Fields for Large Urban Scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 8296–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xue, C.; Zhang, R. SuperNeRF: High-Precision 3-D Reconstruction for Large-Scale Scenes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Sun, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y. MD-NeRF: Enhancing Large-Scale Scene Rendering and Synthesis with Hybrid Point Sampling and Adaptive Scene Decomposition. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Cui, S. Efficient large-scale scene representation with a hybrid of high-resolution grid and plane features. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual Conference, 6–12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 10674–10685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtual Conference, 18–24 July 2021; Volume 139, pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Avrahami, O.; Lischinski, D.; Fried, O. Blended Diffusion for Text-driven Editing of Natural Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 18187–18197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T.; Holynski, A.; Efros, A.A. InstructPix2Pix: Learning to Follow Image Editing Instructions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 18392–18402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N.; Li, Y.; Jampani, V.; Pritch, Y.; Rubinstein, M.; Aberman, K. DreamBooth: Fine Tuning Text-to-Image Diffusion Models for Subject-Driven Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 22500–22510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, A.; Mokady, R.; Tenenbaum, J.; Aberman, K.; Pritch, Y.; Cohen-Or, D. Prompt-to-Prompt Image Editing with Cross-Attention Control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, N.; Jia, K. Fantasia3D: Disentangling Geometry and Appearance for High-quality Text-to-3D Content Creation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 22189–22199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Gao, J.; Tang, L.; Takikawa, T.; Zeng, X.; Huang, X.; Kreis, K.; Fidler, S.; Liu, M.; Lin, T. Magic3D: High-Resolution Text-to-3D Content Creation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, B.; Jain, A.; Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B. DreamFusion: Text-to-3D using 2D Diffusion. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.; Kaza, S.; Poole, B.; Niemeyer, M.; Ruiz, N.; Mildenhall, B.; Zada, S.; Aberman, K.; Rubinstein, M.; Barron, J.T.; et al. DreamBooth3D: Subject-Driven Text-to-3D Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wan, Z.; Wang, C.; Liao, J. Text2NeRF: Text-Driven 3D Scene Generation with Neural Radiance Fields. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2024, 30, 7749–7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Shang, T.; Sun, W.; Wang, S.; Cui, R.; Liu, W.; Sato, H.; Li, H.; et al. BlockFusion: Expandable 3D Scene Generation using Latent Tri-plane Extrapolation. ACM Trans. Graph. 2024, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Man, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. SceneCraft: Layout-Guided 3D Scene Generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 82060–82084. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Fan, T.; Yang, Z.; Bao, H.; Zhang, G.; Cui, Z. SINE: Semantic-driven Image-based NeRF Editing with Prior-guided Editing Field. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 20919–20929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Wang, C.; Lin, L.; Liu, L.; Li, G. DreamEditor: Text-Driven 3D Scene Editing with Neural Fields. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2023 Conference Papers, Sydney, Australia, 12–15 December 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, P.; Tsai, M.; Tseng, H.; Lai, W.; Chiu, W. Stylizing 3D Scene via Implicit Representation and HyperNetwork. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, S.; Philip, J.; Zhang, K.; Bi, S.; Luan, F.; Ghanem, B.; Sunkavalli, K. DATENeRF: Depth-Aware Text-Based Editing of NeRFs. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Volume 15069, pp. 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Huang, S.; Nie, X.; Hui, T.; Liu, L.; Dai, J.; Han, J.; Li, G.; Liu, S. Customize your NeRF: Adaptive Source Driven 3D Scene Editing via Local-Global Iterative Training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 6966–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chai, M.; He, M.; Chen, D.; Liao, J. CLIP-NeRF: Text-and-Image Driven Manipulation of Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 3825–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; He, Y.; Yuan, Y.J.; Lai, Y.K.; Gao, L. StylizedNeRF: Consistent 3D Scene Stylization as Stylized NeRF via 2D-3D Mutual Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 18321–18331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, R.; Chai, M.; He, M.; Chen, D.; Liao, J. NeRF-Art: Text-Driven Neural Radiance Fields Stylization. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2024, 30, 4983–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, A.; Aumentado-Armstrong, T.; Derpanis, K.G.; Kelly, J.; Brubaker, M.A.; Gilitschenski, I.; Levinshtein, A. SPIn-NeRF: Multiview Segmentation and Perceptual Inpainting with Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 20669–20679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Aumentado-Armstrong, T.; Brubaker, M.A.; Kelly, J.; Levinshtein, A.; Derpanis, K.G.; Gilitschenski, I. Watch Your Steps: Local Image and Scene Editing by Text Instructions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Volume 15096, pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Tancik, M.; Efros, A.A.; Holynski, A.; Kanazawa, A. Instruct-NeRF2NeRF: Editing 3D Scenes with Instructions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 19683–19693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, Y.X. ViCA-NeRF: View-Consistency-Aware 3D Editing of Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36, pp. 61466–61477. [Google Scholar]

- Dihlmann, J.; Engelhardt, A.; Lensch, H.P.A. SIGNeRF: Scene Integrated Generation for Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 6679–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Ding, W. UAV-ENeRF: Text-Driven UAV Scene Editing with Neural Radiance Fields. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual Conference, 6–14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Tancik, M.; Weber, E.; Ng, E.; Li, R.; Yi, B.; Wang, T.; Kristoffersen, A.; Austin, J.; Salahi, K.; Ahuja, A.; et al. Nerfstudio: A Modular Framework for Neural Radiance Field Development. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2023 Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberger, J.L.; Frahm, J.M. Structure-from-Motion Revisited. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4104–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yin, F.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, T.; Yu, G.; Fan, J. A Large-Scale Outdoor Multi-modal Dataset and Benchmark for Novel View Synthesis and Implicit Scene Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 7523–7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| View 1 (Left) | View 2 (Upper Right) | View 3 (Lower Right) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | ||

| Scene 1 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 0.2064 | 0.1852 | 0.4015 | 0.5603 | 0.2064 | 0.1750 | 0.4368 | 0.5256 | 0.1998 | 0.1669 | 0.3211 | 0.3597 |

| “Ignite the grass” | 0.1899 | 0.1398 | 0.1385 | 0.6148 | 0.2288 | 0.1564 | 0.1760 | 0.5799 | 0.2032 | 0.1625 | 0.1585 | 0.5704 | |

| “Cars added to the grass” | 0.0900 | 0.2756 | 0.2208 | 0.5800 | 0.1332 | 0.1468 | 0.2008 | 0.5359 | 0.1033 | 0.2121 | 0.2988 | 0.7208 | |

| “Add trees to the grassy area” | 0.1540 | 0.1357 | 0.3446 | 0.3772 | 0.1787 | 0.0716 | 0.3056 | 0.5440 | 0.2043 | 0.1444 | 0.3194 | 0.4520 | |

| Scene 2 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 0.2155 | 0.1226 | 0.2943 | 0.4503 | 0.2604 | 0.1504 | 0.3845 | 0.4545 | 0.2443 | 0.1379 | 0.2809 | 0.5062 |

| “Leaves turn red” | 0.2429 | 0.2587 | 0.3953 | 0.4890 | 0.2712 | 0.2420 | 0.3431 | 0.4313 | 0.2054 | 0.1812 | 0.4140 | 0.4578 | |

| “Turn into autumn” | 0.2092 | 0.2436 | 0.3805 | 0.4563 | 0.1682 | 0.3364 | 0.3637 | 0.3993 | 0.1918 | 0.2983 | 0.4075 | 0.6712 | |

| “Turn into night” | 0.1497 | 0.1741 | 0.4870 | 0.5490 | 0.1347 | 0.1799 | 0.3806 | 0.4839 | 0.1256 | 0.1802 | 0.4497 | 0.4761 | |

| View 1 (Left) | View 2 (Upper Right) | View 3 (Lower Right) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | ||

| Scene 1 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 0.2632 | 0.2781 | 0.2510 | 0.2847 | 0.2393 | 0.2539 | 0.2747 | 0.2939 | 0.2347 | 0.2566 | 0.2542 | 0.2905 |

| “Ignite the grass” | 0.2310 | 0.2219 | 0.2385 | 0.2673 | 0.2371 | 0.2357 | 0.2338 | 0.2700 | 0.2322 | 0.2324 | 0.2495 | 0.2773 | |

| “Cars added to the grass” | 0.2244 | 0.2996 | 0.2471 | 0.3010 | 0.2294 | 0.2588 | 0.2478 | 0.2869 | 0.2301 | 0.2830 | 0.2590 | 0.3020 | |

| “Add trees to the grassy area” | 0.2494 | 0.2488 | 0.2715 | 0.2795 | 0.2542 | 0.2124 | 0.2700 | 0.2891 | 0.2537 | 0.2720 | 0.2695 | 0.2888 | |

| Scene 2 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 0.2418 | 0.2374 | 0.2512 | 0.2764 | 0.2510 | 0.2473 | 0.2472 | 0.2690 | 0.2651 | 0.2363 | 0.2539 | 0.2864 |

| “Leaves turn red” | 0.2527 | 0.2993 | 0.2600 | 0.2583 | 0.2546 | 0.2952 | 0.2316 | 0.2517 | 0.2612 | 0.2463 | 0.2793 | 0.2732 | |

| “Turn into autumn” | 0.2146 | 0.2460 | 0.2404 | 0.2325 | 0.2112 | 0.2703 | 0.2405 | 0.2288 | 0.2202 | 0.2825 | 0.2311 | 0.2405 | |

| “Turn into night” | 0.2207 | 0.2345 | 0.2159 | 0.2189 | 0.2209 | 0.2371 | 0.2141 | 0.2394 | 0.2162 | 0.2356 | 0.2078 | 0.2170 | |

| View 1 (Left) | View 2 (Upper Right) | View 3 (Lower Right) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | ||

| Scene 1 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 0.0567 | 0.0360 | 0.2080 | 0.2153 | 0.0472 | 0.0481 | 0.2111 | 0.2380 | 0.0493 | 0.0336 | 0.1682 | 0.1746 |

| “Ignite the grass” | −0.0037 | 0.0533 | −0.0346 | 0.3906 | 0.0249 | 0.0650 | −0.0243 | 0.3176 | 0.0107 | 0.0441 | −0.0530 | 0.3889 | |

| “Cars added to the grass” | −0.1095 | 0.1301 | −0.0216 | 0.2720 | −0.0506 | 0.0325 | −0.0178 | 0.1982 | −0.0925 | 0.0880 | 0.0481 | 0.2438 | |

| “Add trees to the grassy area” | −0.0753 | −0.0631 | 0.0749 | 0.1107 | −0.0569 | −0.1008 | 0.0536 | 0.1362 | −0.0172 | −0.0236 | 0.0745 | 0.1257 | |

| Scene 2 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 0.0862 | −0.0123 | 0.1169 | 0.2252 | 0.1182 | 0.0204 | 0.2368 | 0.2456 | 0.0994 | 0.0171 | 0.0892 | 0.2495 |

| “Leaves turn red” | 0.0801 | 0.1948 | 0.2191 | 0.2278 | 0.1010 | 0.1532 | 0.1991 | 0.2050 | 0.0395 | 0.1013 | 0.2251 | 0.2183 | |

| “Turn into autumn” | 0.0185 | 0.1393 | 0.2294 | 0.2418 | 0.0246 | 0.1964 | 0.2139 | 0.2209 | 0.0418 | 0.2108 | 0.2322 | 0.3064 | |

| “Turn into night” | 0.0486 | 0.1356 | 0.2668 | 0.2983 | 0.0193 | 0.1453 | 0.2224 | 0.2427 | 0.0084 | 0.1466 | 0.2040 | 0.1735 | |

| View 1 (Left) | View 2 (Upper Right) | View 3 (Lower Right) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | Custom [42] | N2N [48] | VICA [49] | Ours | ||

| Scene 1 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 34.4920 | 48.6211 | 12.9090 | 6.8060 | 23.4556 | 52.1778 | 11.9449 | 9.2797 | 25.4060 | 53.8359 | 19.6751 | 18.6330 |

| “Ignite the grass” | 14.7334 | 91.9134 | 28.6792 | 10.7525 | 12.9733 | 82.7078 | 14.4974 | 9.3116 | 14.6903 | 49.2999 | 16.3603 | 13.7242 | |

| “Cars added to the grass” | 17.9289 | 35.2548 | 9.4970 | 8.7258 | 20.9988 | 95.4384 | 12.9834 | 7.0378 | 20.4781 | 55.1608 | 9.6607 | 4.7171 | |

| “Add trees to the grassy area” | 12.5062 | 22.3538 | 9.1203 | 9.8225 | 11.7114 | 35.1213 | 10.4524 | 5.0509 | 13.3830 | 51.4680 | 10.9406 | 7.2628 | |

| Scene 2 | “Grassland turns into flower fields” | 32.2636 | 67.6249 | 16.8117 | 11.9987 | 25.1654 | 59.1784 | 17.1397 | 12.5625 | 30.0600 | 67.6947 | 15.6444 | 10.4481 |

| “Leaves turn red” | 22.4586 | 80.2274 | 15.2946 | 8.8632 | 19.4652 | 70.2552 | 17.0026 | 10.4532 | 28.1150 | 81.8723 | 15.5323 | 10.8470 | |

| “Turn into autumn” | 12.0145 | 37.1571 | 16.1654 | 9.9492 | 24.2251 | 23.3969 | 16.7596 | 12.3718 | 22.2113 | 44.0571 | 12.7033 | 5.5276 | |

| “Turn into night” | 62.0233 | 132.4212 | 8.7978 | 7.7500 | 59.6868 | 132.4908 | 13.0273 | 8.9125 | 60.3352 | 131.2543 | 7.2353 | 5.6094 | |

| CLIP-TIDS ↑ | CLIP-DC ↑ | BRISQUE ↓ | TDB ↑ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Center | Right | Left | Center | Right | Left | Center | Right | Left | Center | Right | |

| w/o RNTR | 0.2583 | 0.2793 | 0.2734 | 0.3074 | 0.3682 | 0.2269 | 24.2272 | 26.8964 | 27.7686 | 0.4035 | 0.4479 | 0.3429 |

| w/ RNTR | 0.2642 | 0.2642 | 0.2377 | 0.3516 | 0.3806 | 0.2439 | 17.5011 | 19.3349 | 16.0689 | 0.4860 | 0.4929 | 0.3908 |

| w/o VP | 0.2122 | 0.2057 | 0.2058 | 0.0588 | 0.0658 | 0.0319 | 21.5104 | 16.9307 | 21.9204 | 0.2004 | 0.2166 | 0.1748 |

| w/ VP | 0.2264 | 0.2213 | 0.2240 | 0.0890 | 0.0911 | 0.0746 | 21.5408 | 16.8403 | 22.3957 | 0.2331 | 0.2496 | 0.2181 |

| w/o DR | 0.2651 | 0.2650 | 0.2598 | 0.2542 | 0.2571 | 0.2539 | 7.0661 | 9.8522 | 14.7605 | 0.5728 | 0.5042 | 0.4290 |

| w/ DR | 0.2759 | 0.2666 | 0.2686 | 0.2825 | 0.2644 | 0.2659 | 5.1188 | 5.2124 | 10.1656 | 0.7098 | 0.6694 | 0.5101 |

| w/o AB | 0.2440 | 0.2764 | 0.2861 | 0.1865 | 0.2070 | 0.2399 | 12.3056 | 16.0577 | 11.9057 | 0.3830 | 0.3924 | 0.4735 |

| w/ AB | 0.2507 | 0.2583 | 0.2839 | 0.1733 | 0.1737 | 0.2310 | 7.5930 | 10.0552 | 10.6847 | 0.4539 | 0.4140 | 0.4823 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wu, S.; Deng, W. UAVEdit-NeRFDiff: Controllable Region Editing for Large-Scale UAV Scenes Using Neural Radiance Fields and Diffusion Models. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122069

Ye C, Chen X, Chen Z, Sun Z, Wu S, Deng W. UAVEdit-NeRFDiff: Controllable Region Editing for Large-Scale UAV Scenes Using Neural Radiance Fields and Diffusion Models. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122069

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Chenghong, Xueyun Chen, Zhihong Chen, Zhenyu Sun, Shaojie Wu, and Wenqin Deng. 2025. "UAVEdit-NeRFDiff: Controllable Region Editing for Large-Scale UAV Scenes Using Neural Radiance Fields and Diffusion Models" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122069

APA StyleYe, C., Chen, X., Chen, Z., Sun, Z., Wu, S., & Deng, W. (2025). UAVEdit-NeRFDiff: Controllable Region Editing for Large-Scale UAV Scenes Using Neural Radiance Fields and Diffusion Models. Symmetry, 17(12), 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122069