Urban High-Rise Building Asymmetric Settlement Induced by Subsurface Geological Anomalies: A Case Analysis of Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Engineering Background

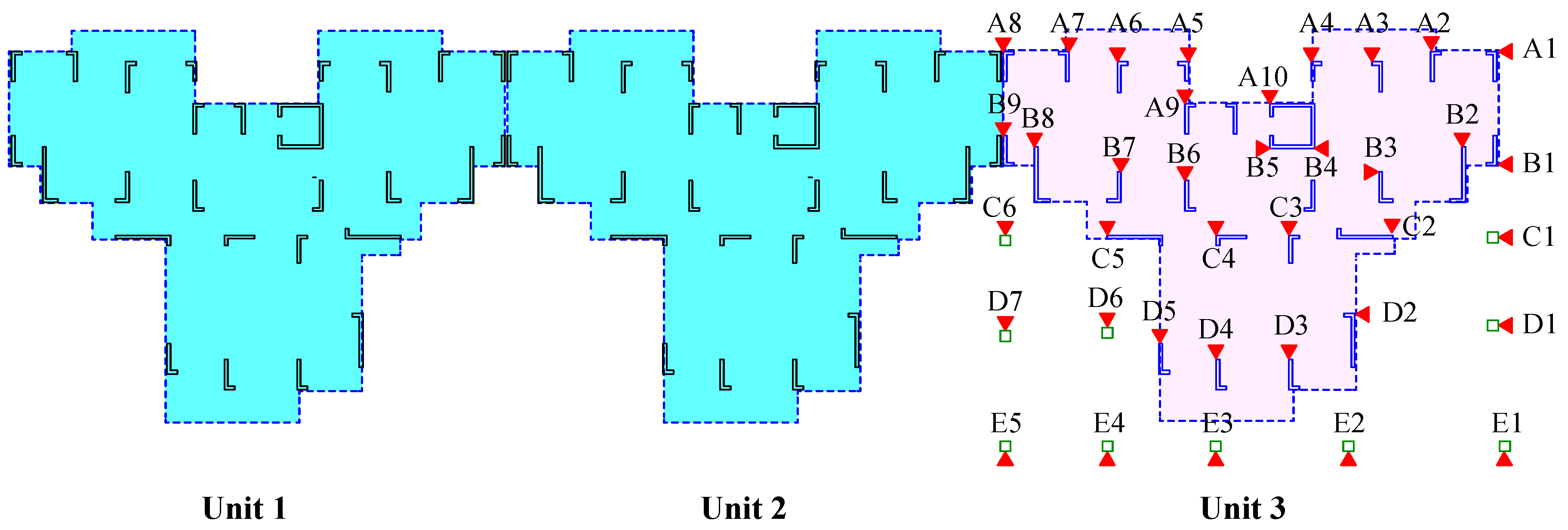

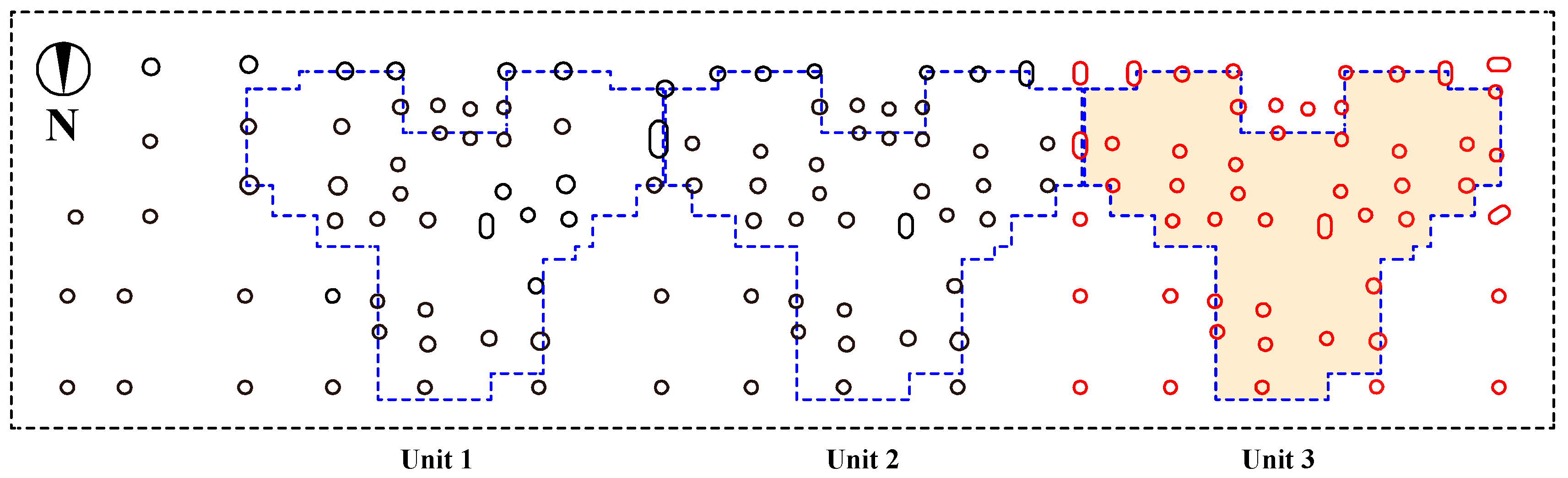

2.1. Engineering Overview

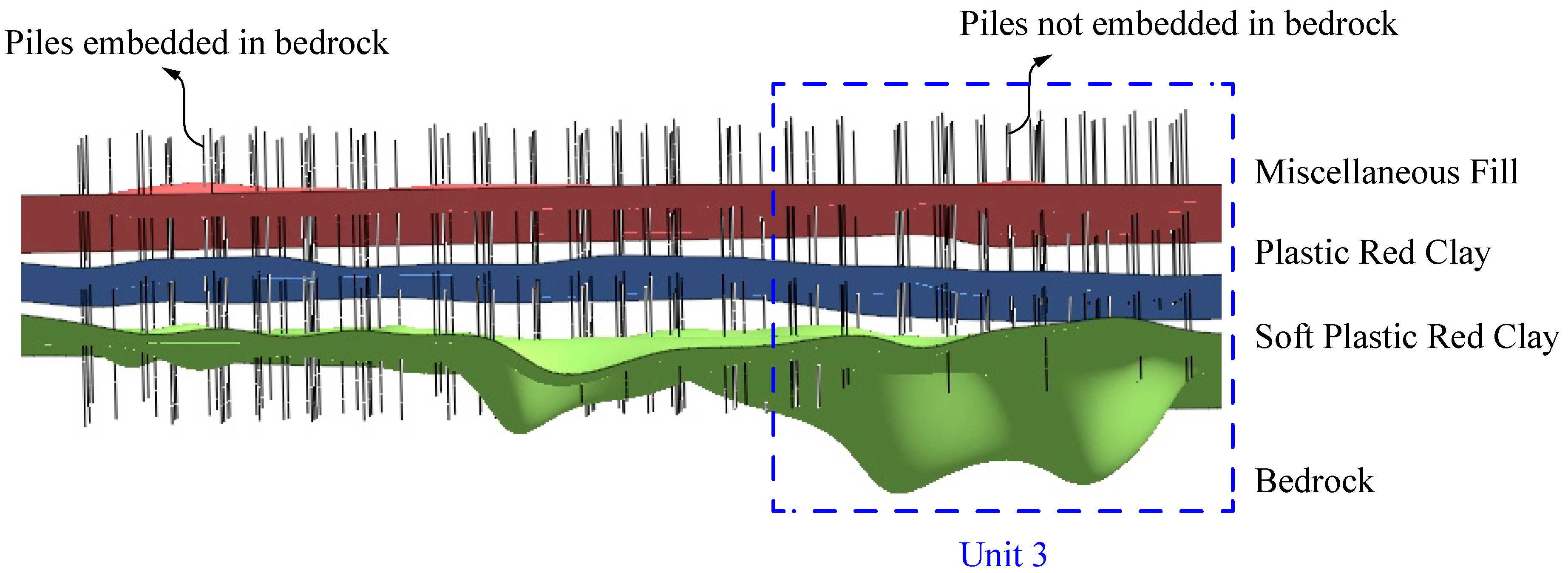

2.2. Engineering Geology

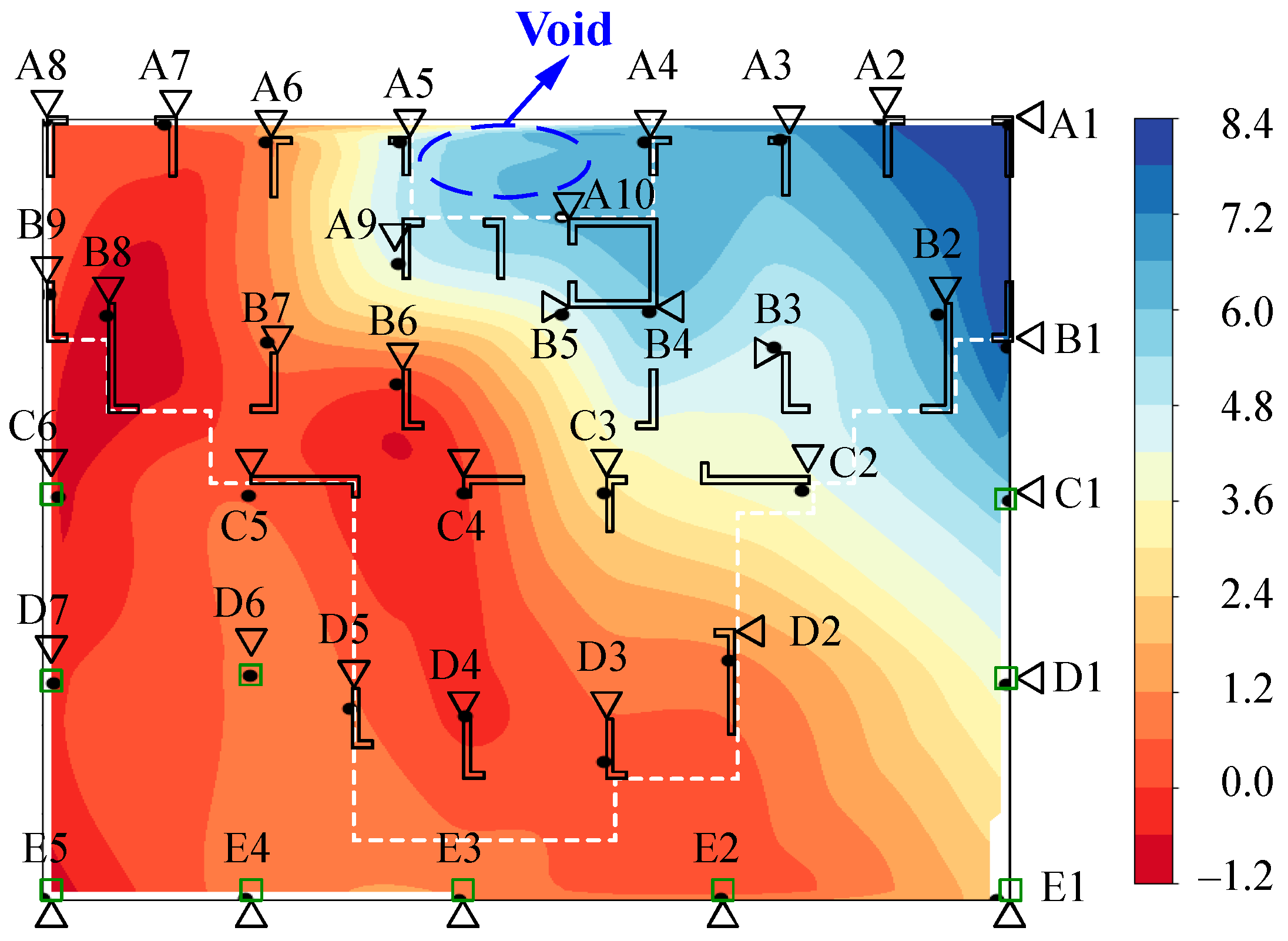

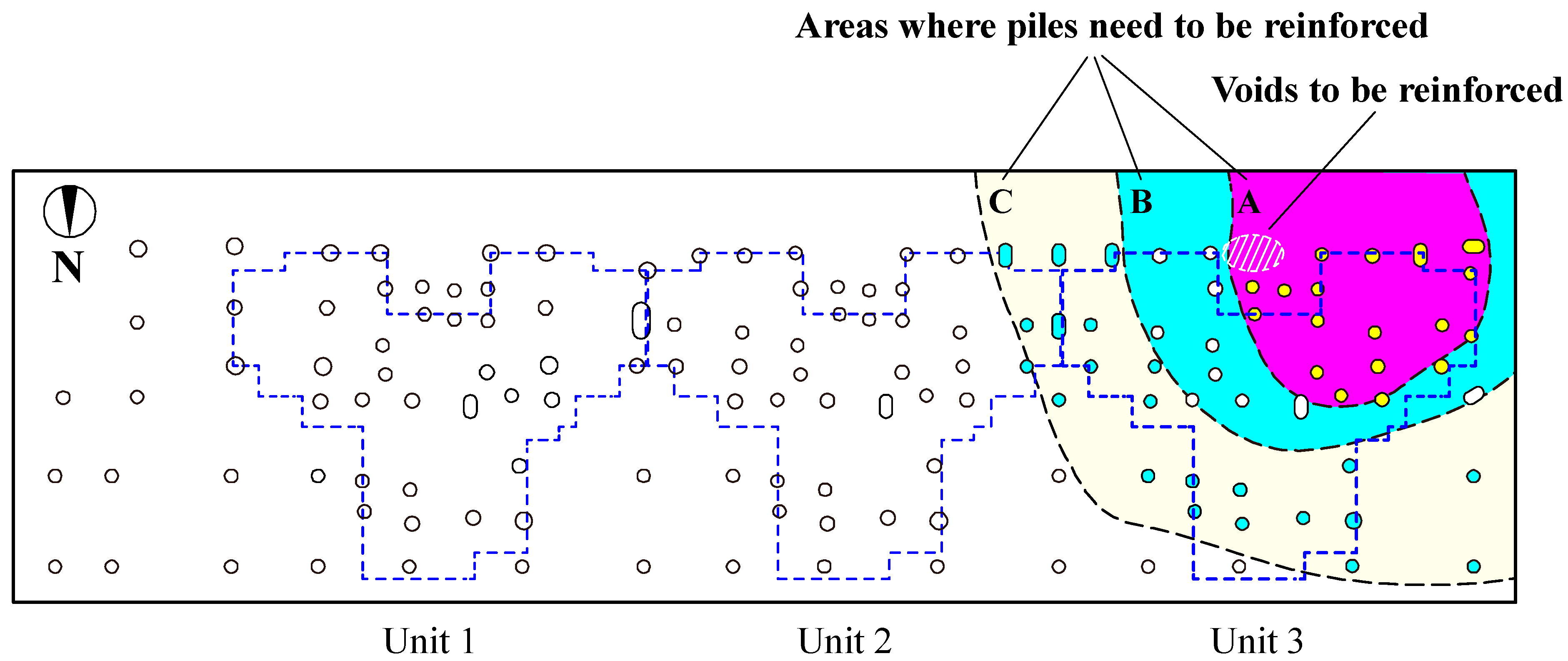

2.3. Field Investigation of Asymmetrical Settlement in Buildings

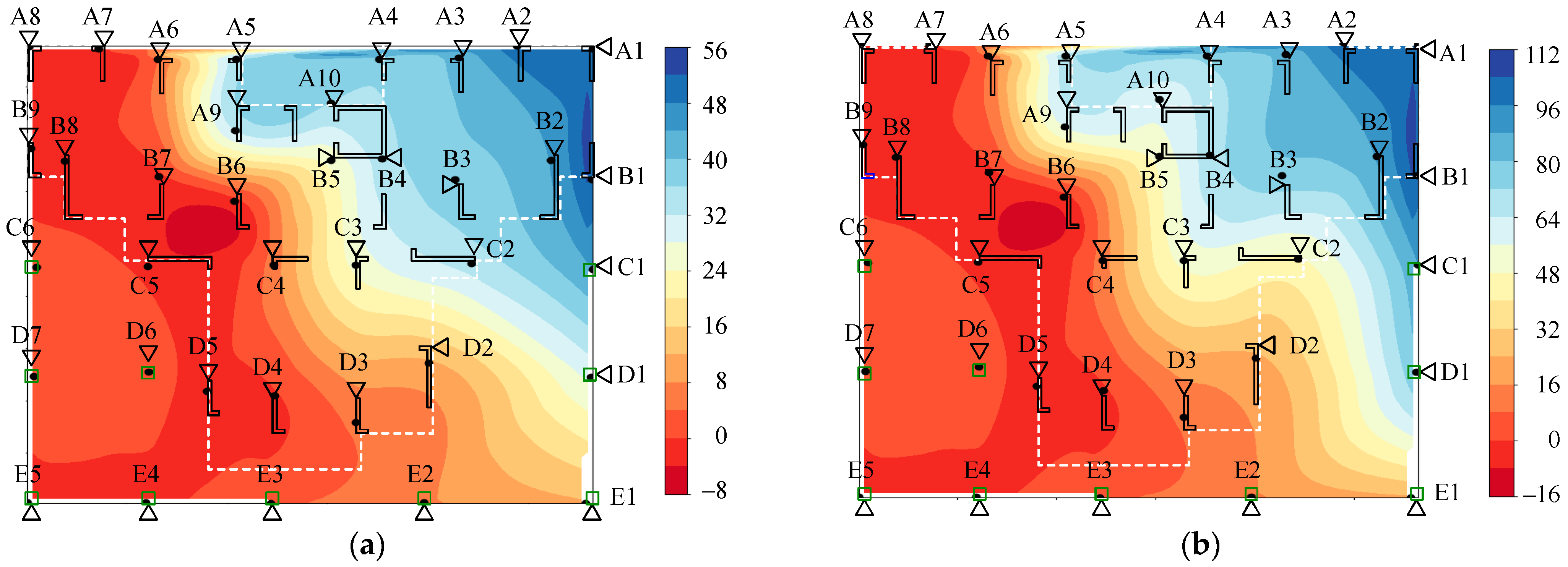

2.3.1. Asymmetric Settlement of Buildings

2.3.2. Causes of Building Asymmetric Settlement

3. Theoretical Analysis of Pile Foundation Settlement Through Local Geological Anomalies

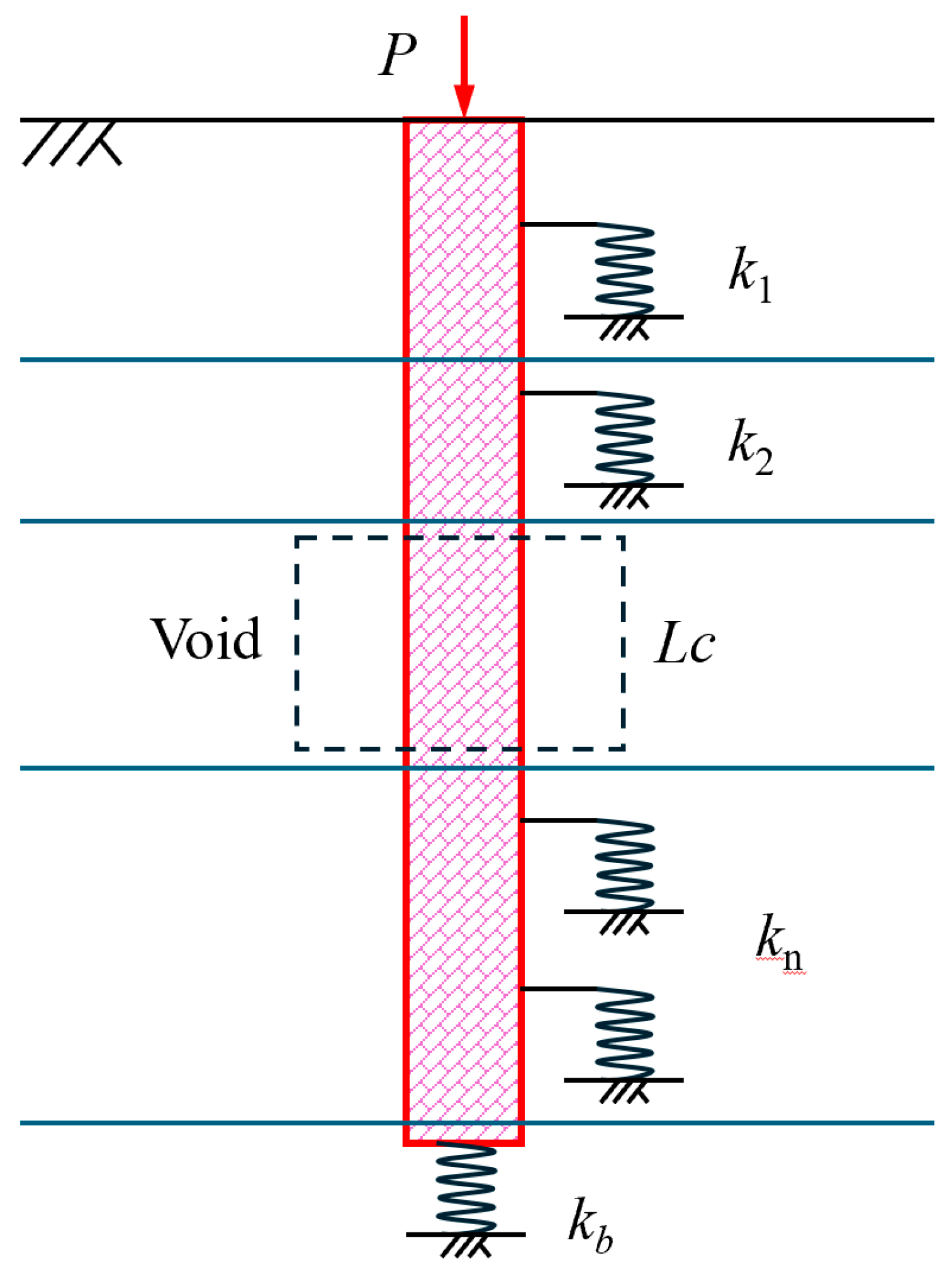

3.1. Model Formulation

3.2. Assumptions

- (1)

- Pile assumptions: The pile behaves as a one-dimensional elastic rod with uniform cross-section, neglecting self-weight and nonlinear skin friction.

- (2)

- Soil assumptions: Each soil layer is linear elastic, providing lateral support to the pile through a linear spring with stiffness ki. Poisson’s ratio vi is assumed known for each layer.

- (3)

- Void assumptions: Within the void, lateral support is absent. The void is bounded by z1 and z2, with height Lc= z2 − z1.

- (4)

- Boundary conditions: The pile head is subjected to a concentrated load P, while the base interacts with a spring of stiffness kb.

- (5)

- Segment continuity: Displacement and axial force are continuous across layer interfaces and at the top and bottom boundaries of voids.

3.3. Governing Equations

3.4. Boundary Conditions and Segment Continuity

- (1)

- Pile head load:representing equilibrium under the applied axial load.

- (2)

- Pile base support:accounting for interaction with the base spring.

- (3)

- Segment continuity: At layer interfaces or void boundaries, displacement and axial force are continuous:and for void boundaries:

3.5. Solution Procedure

3.6. Single-Layer Homogeneous

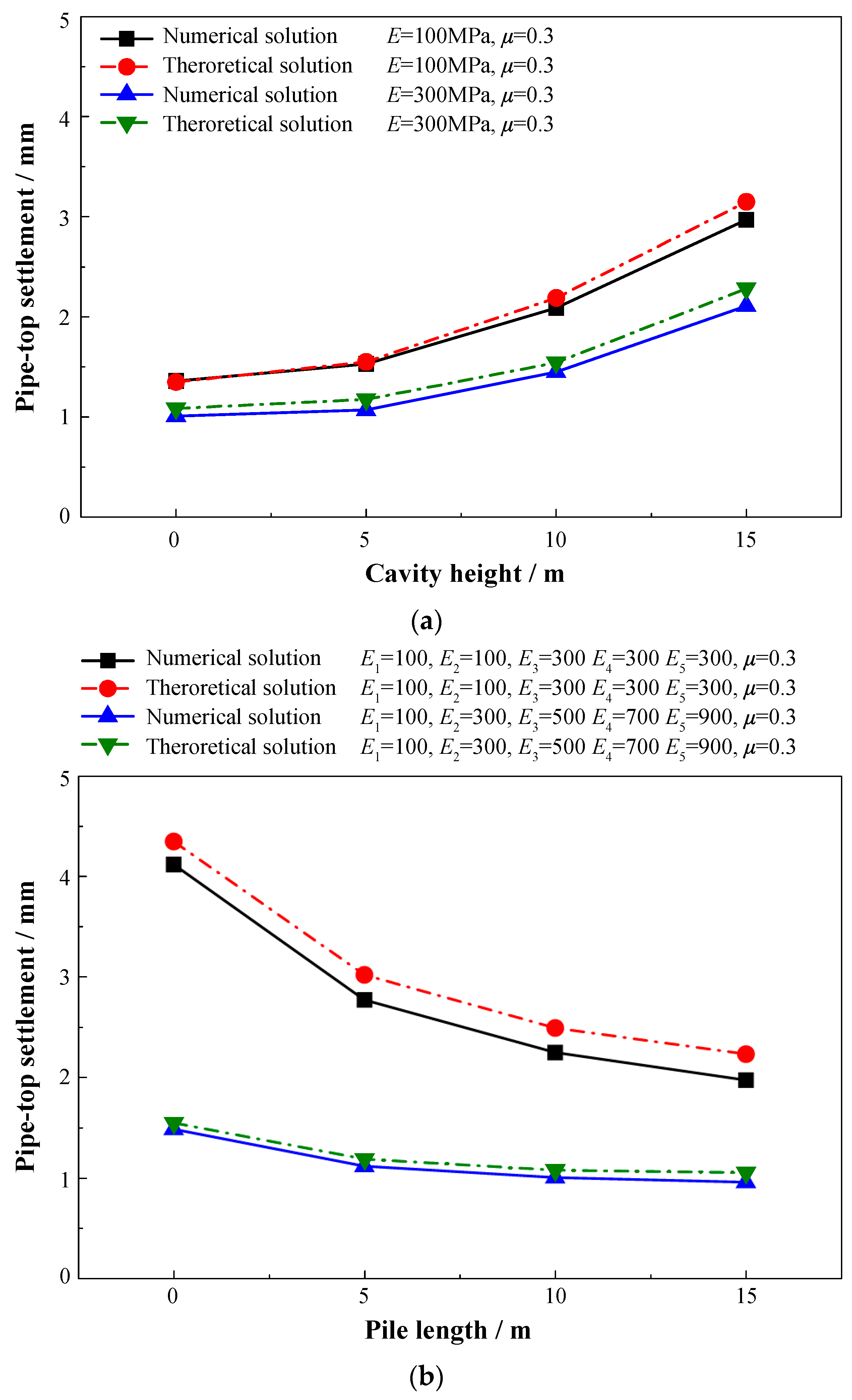

3.7. Verification of Theoretical Models Based on Numerical Simulation

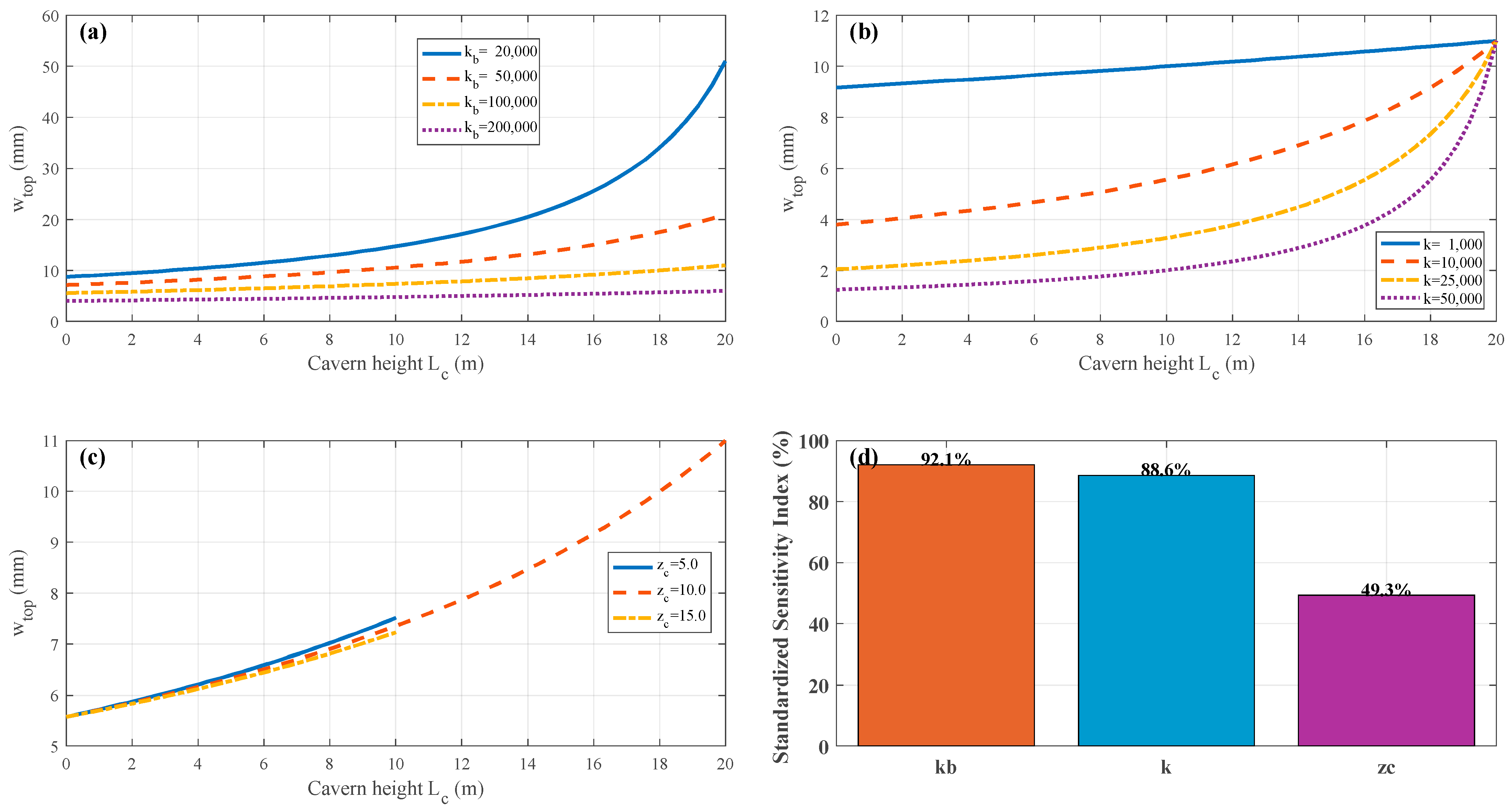

3.8. Parametric Analyses

4. Uneven Settlement of High-Rise Buildings Caused by Pile Foundation

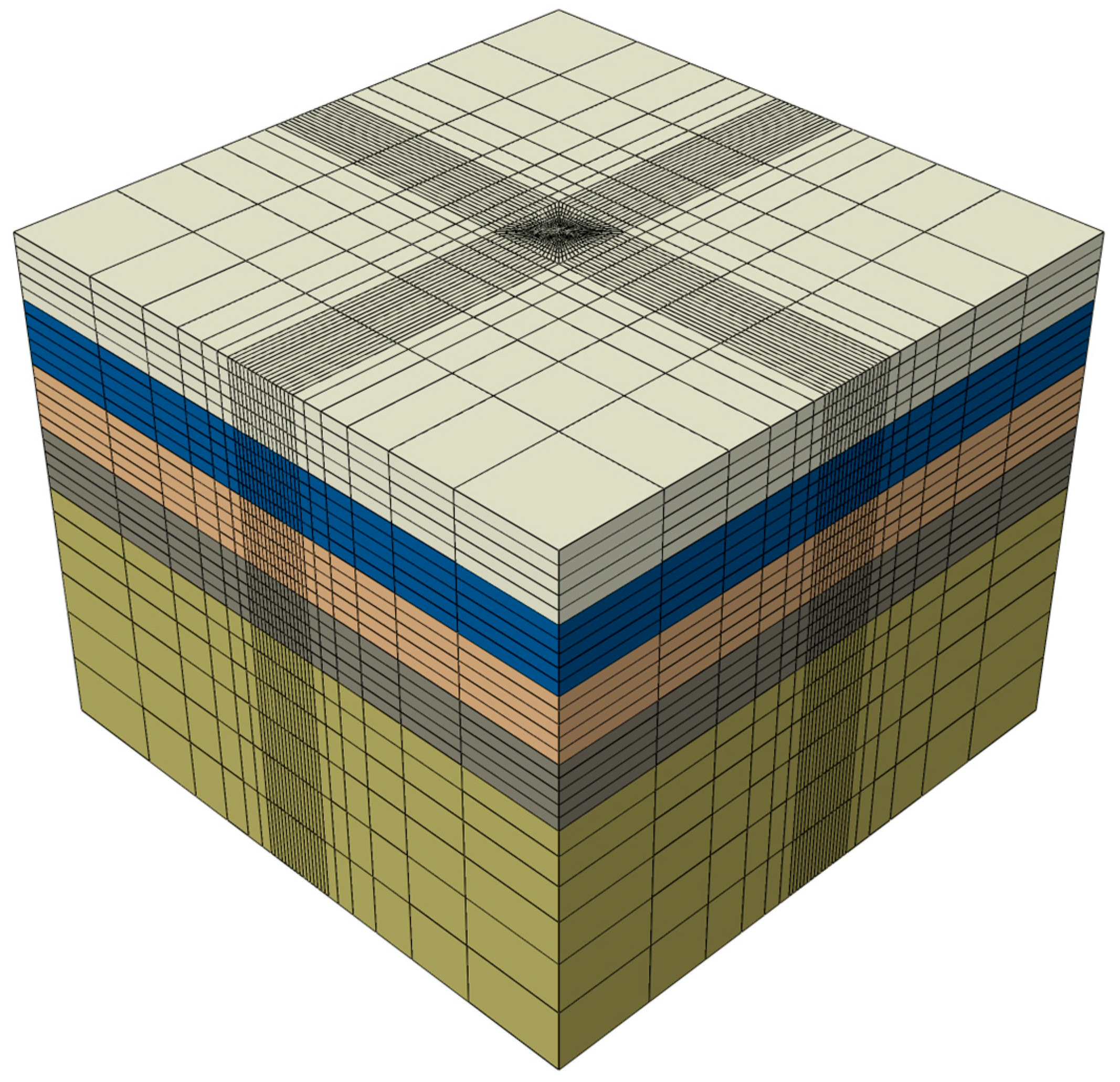

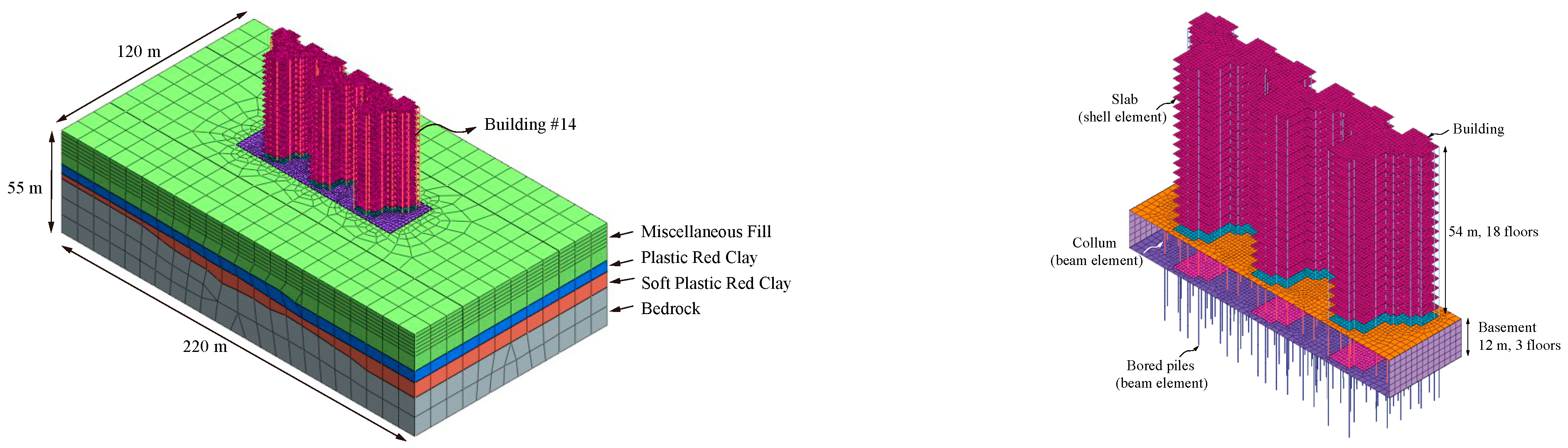

4.1. Numerical Model

4.2. Material Parameters

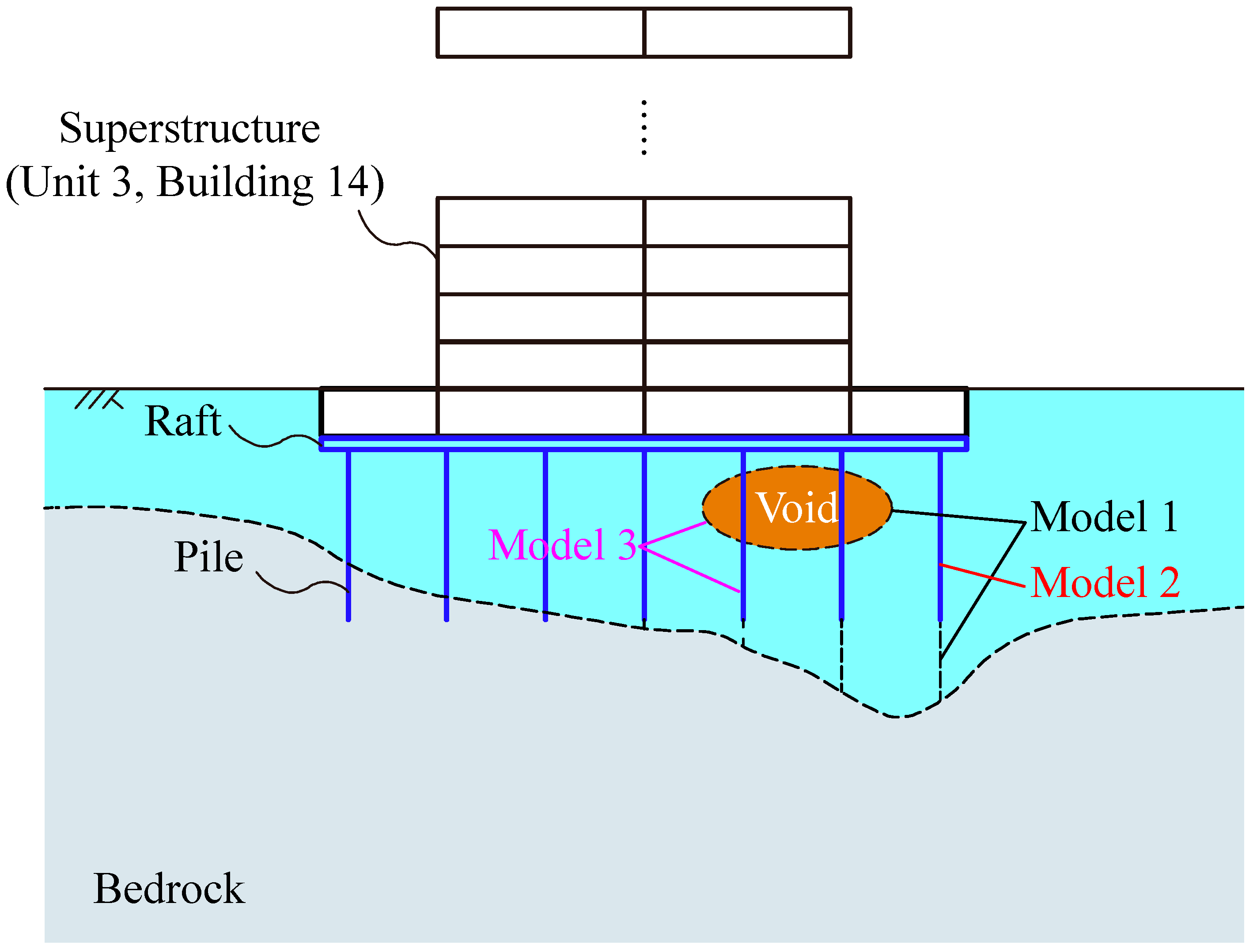

4.3. Simulation Scheme

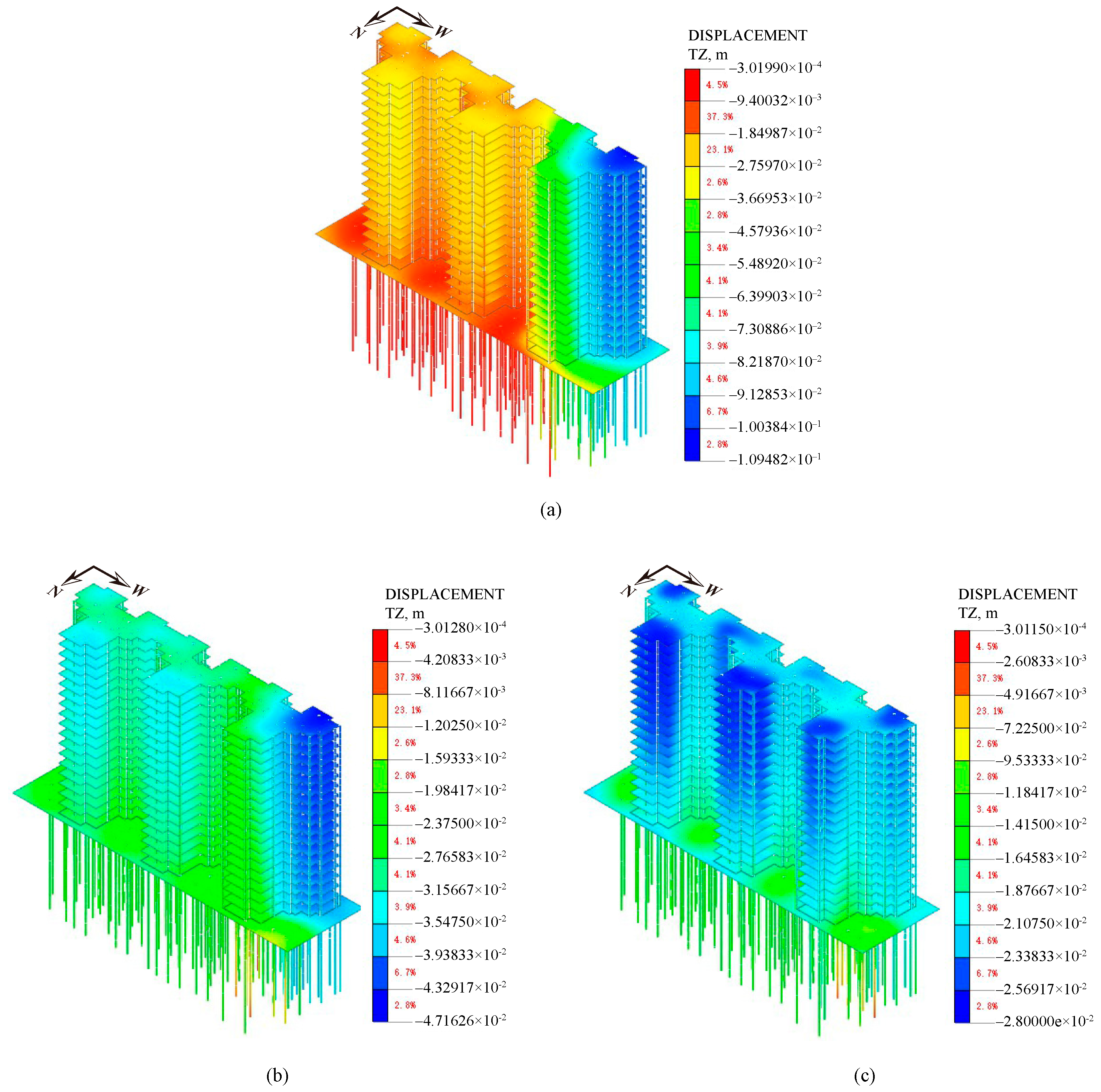

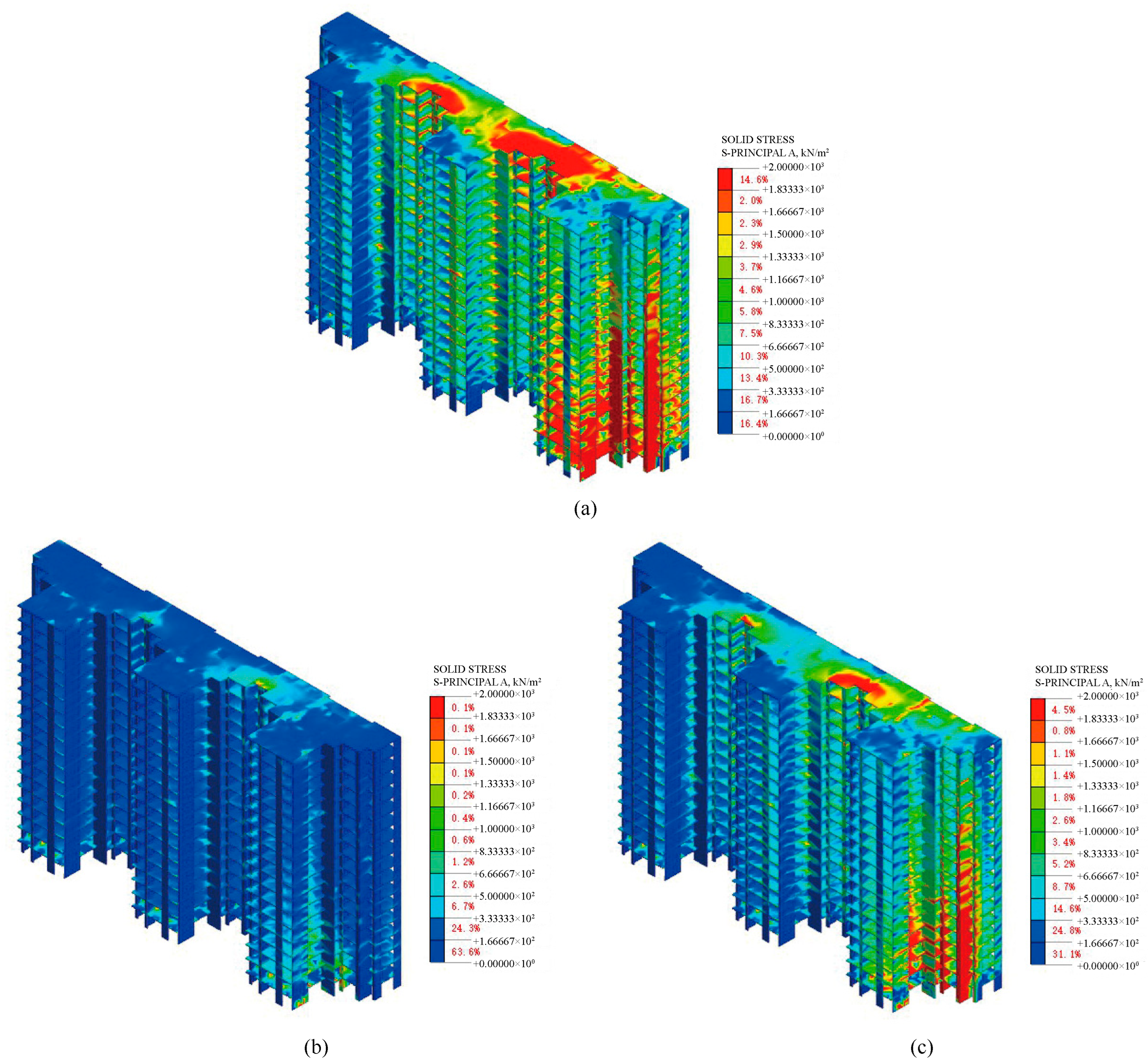

4.4. Analysis of Numerical Results

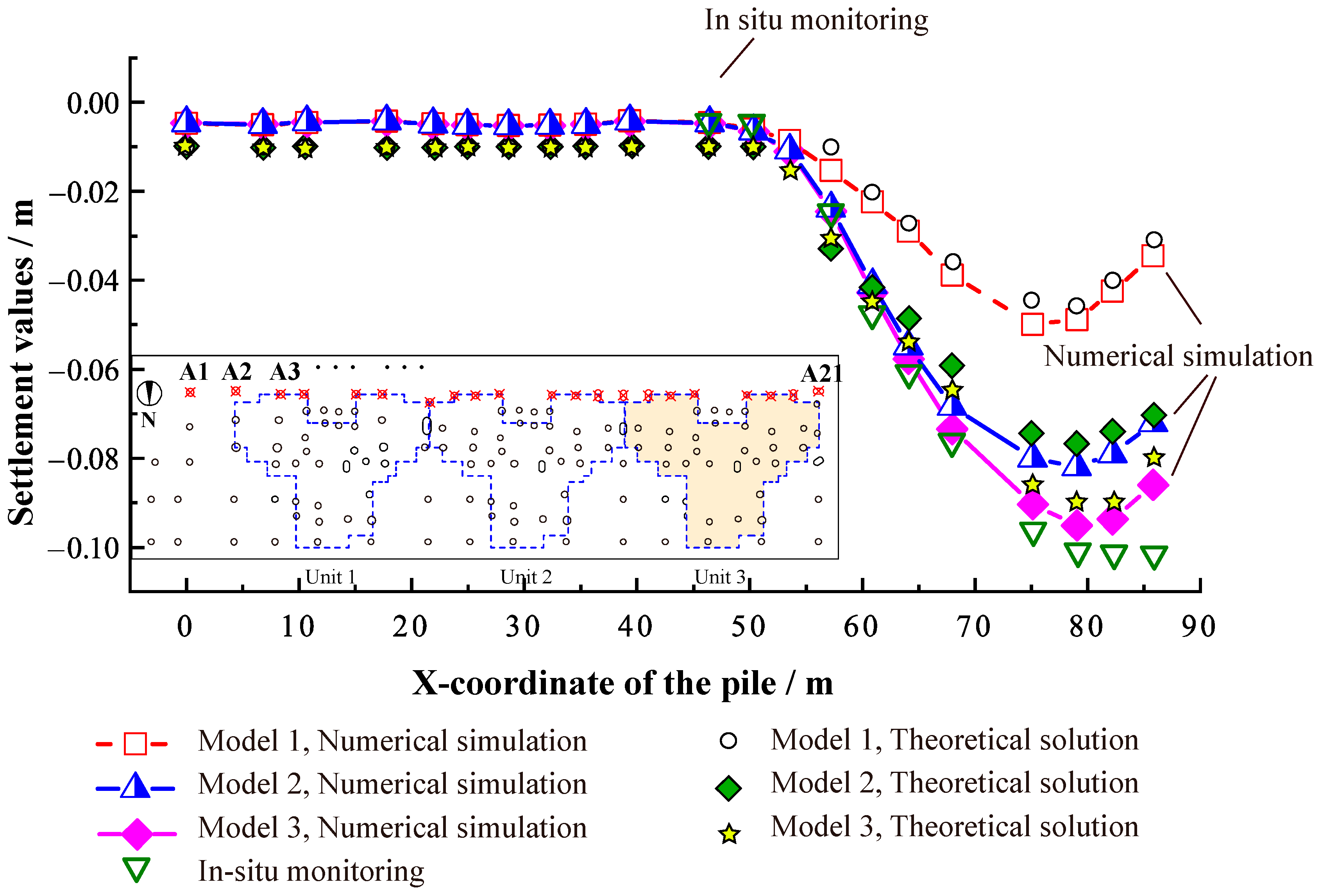

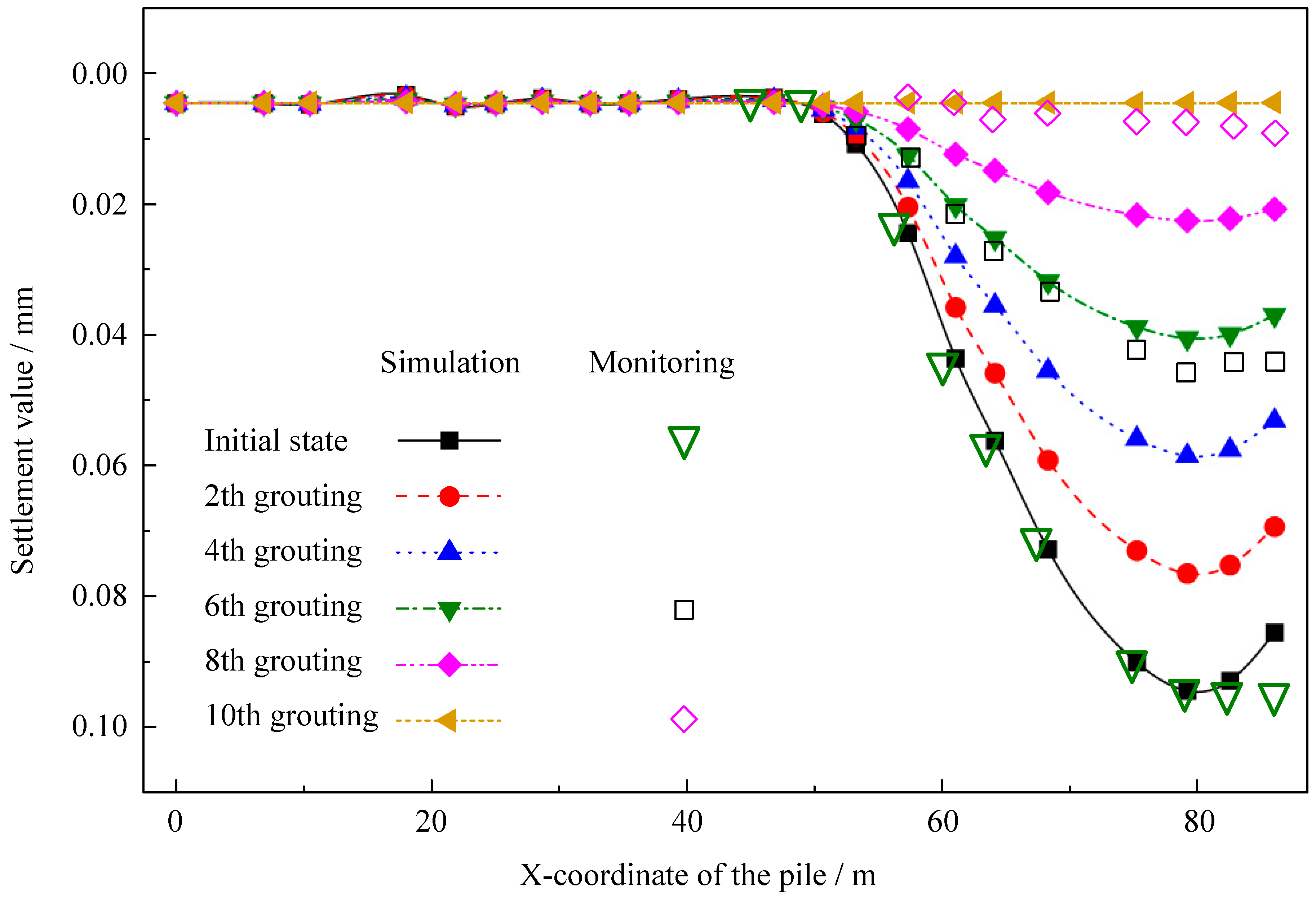

4.4.1. Comparison of Theoretical, Numerical, and Monitoring Values for Pile Cap Settlement

4.4.2. Settlement of Superstructure

4.4.3. Stress of the Superstructure

5. Design of Building Uplift and Correction Program

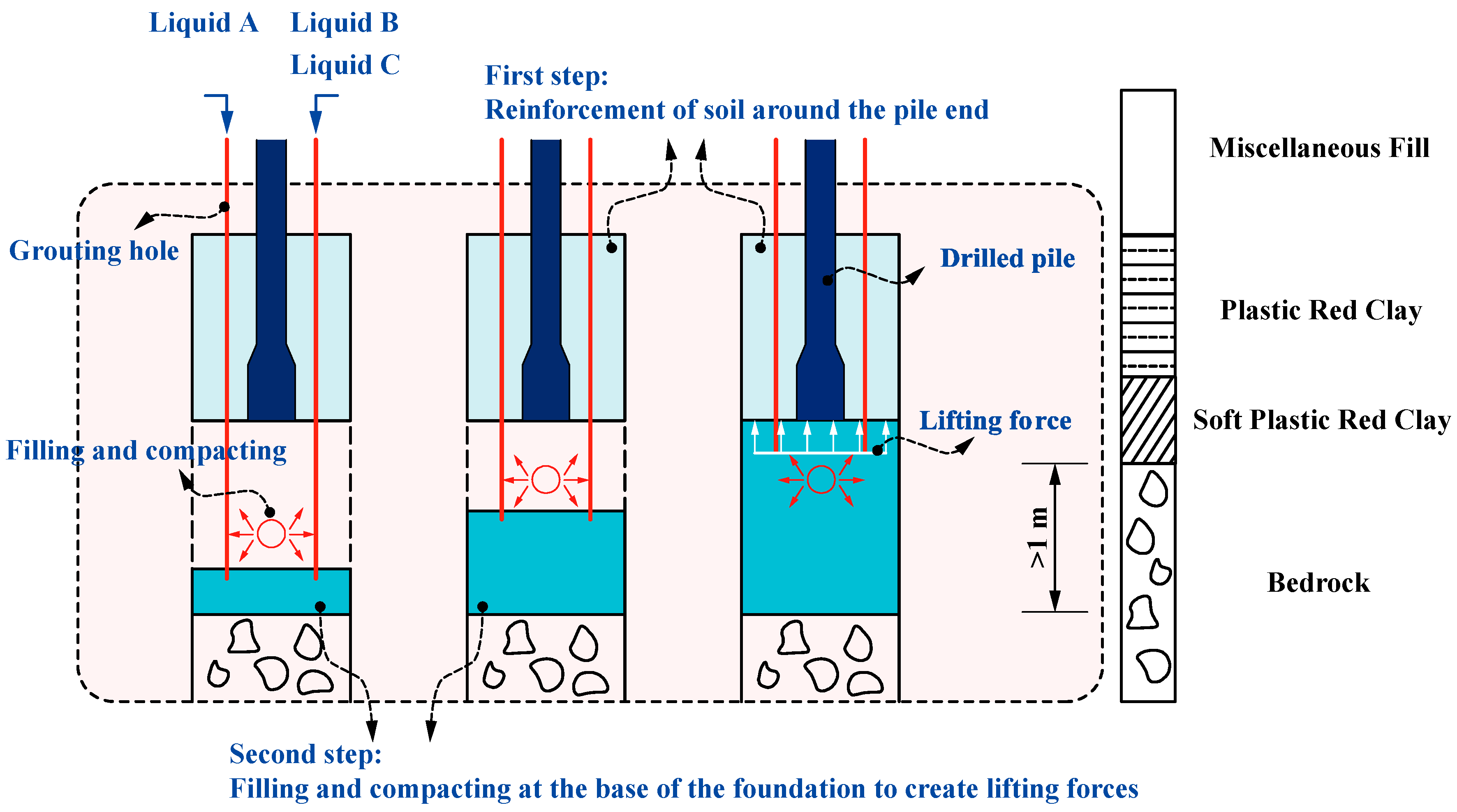

5.1. Principle of Foundation Reinforcement Lifting

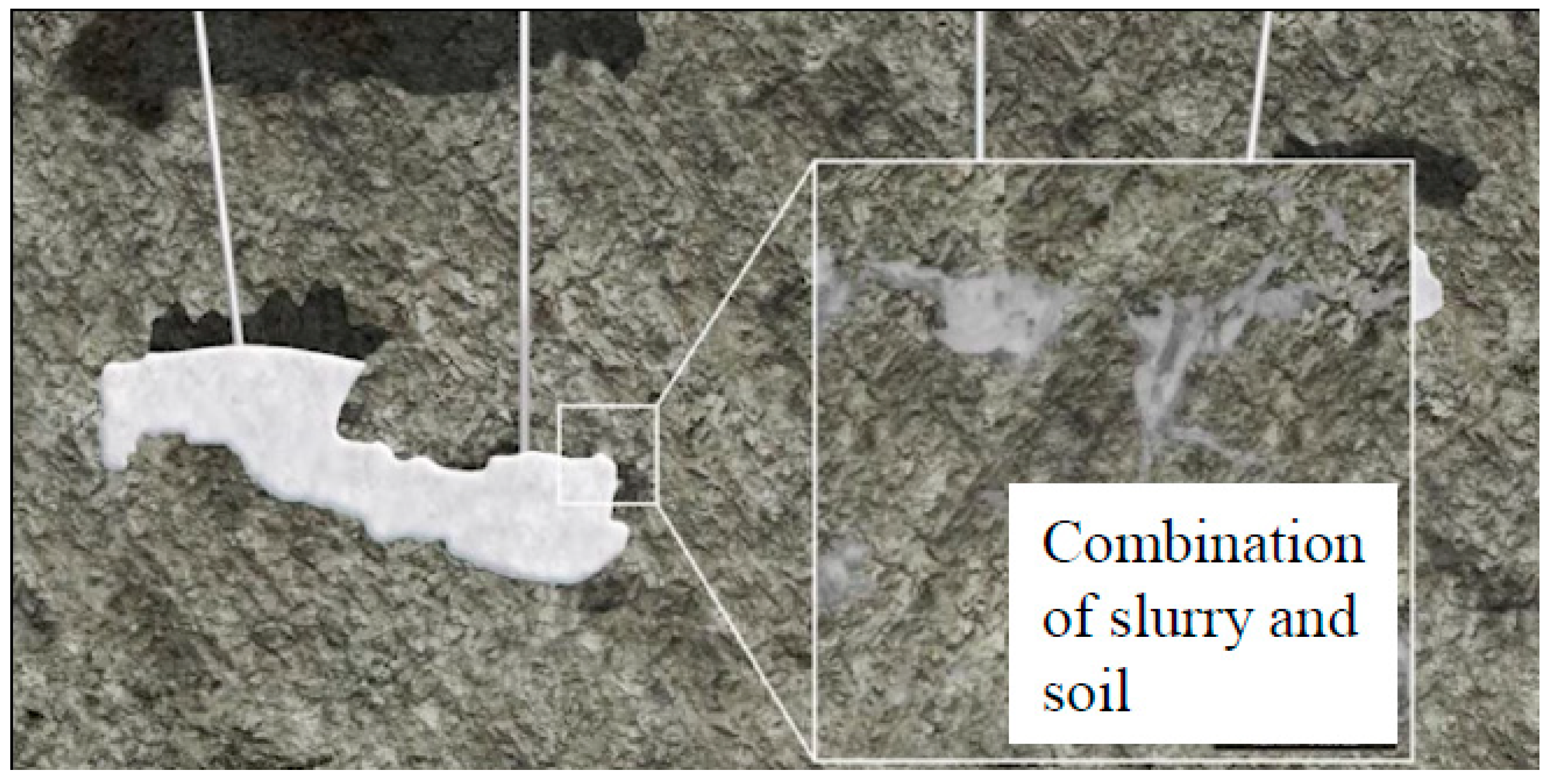

5.1.1. Grouting and Backfilling of Geological Voids

5.1.2. Elevation of Piles by Grouting

5.2. Feasibility Analysis Based on Numerical Simulation

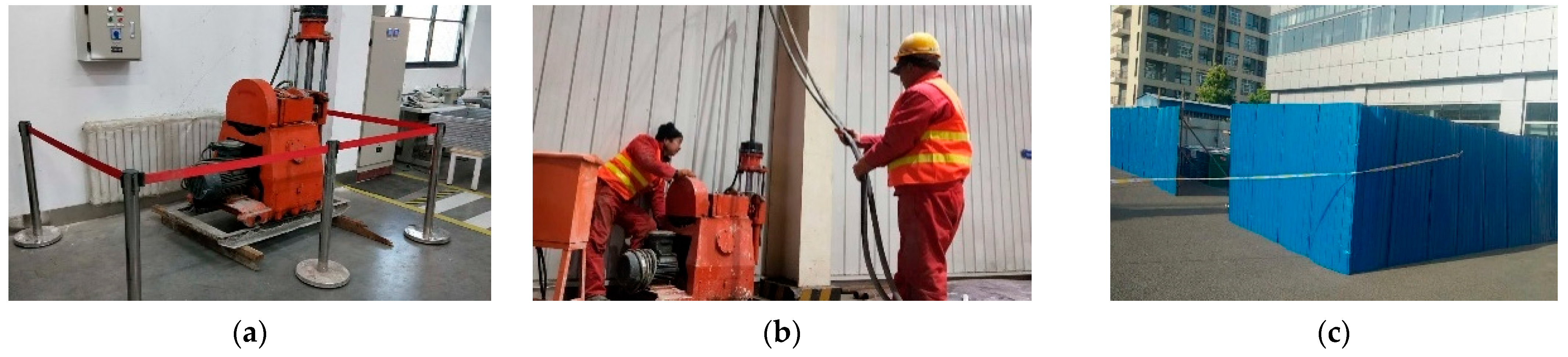

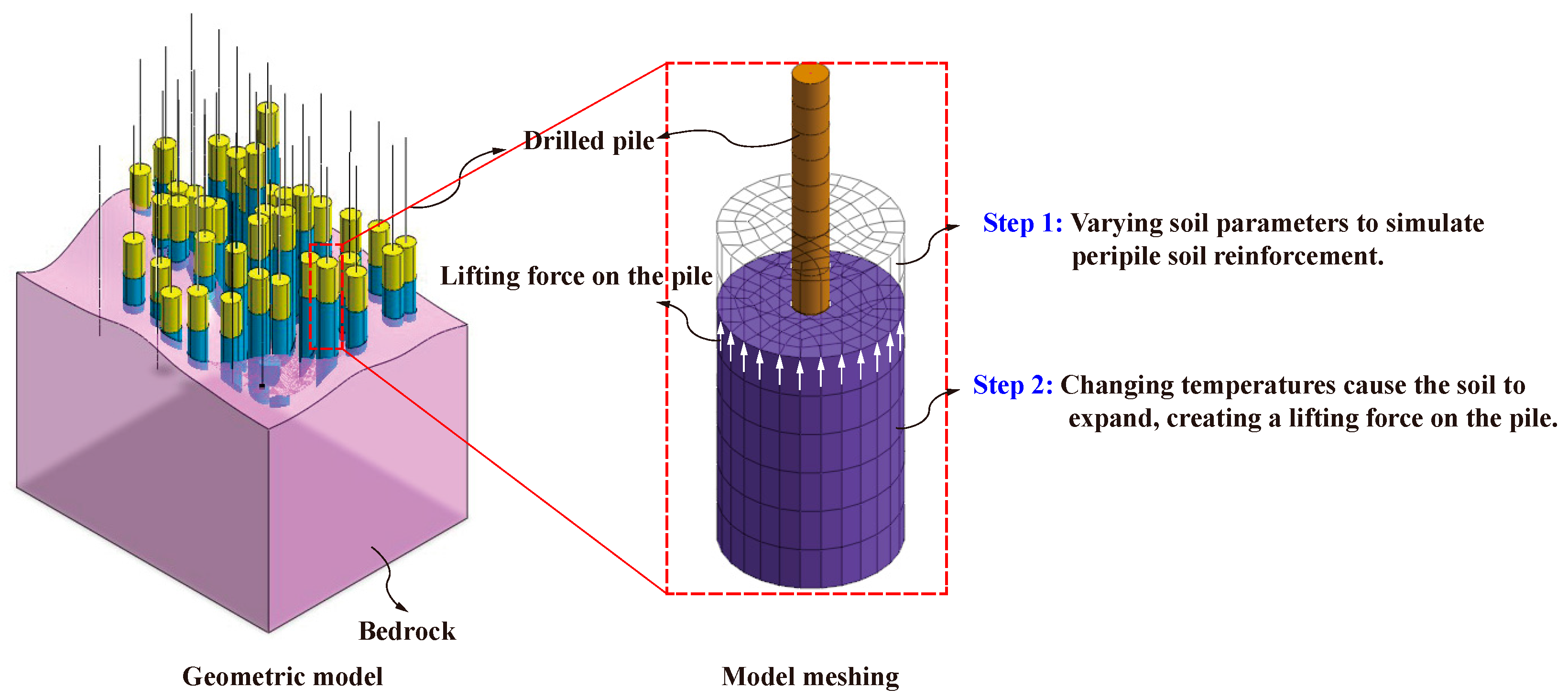

5.2.1. Simulation Method

5.2.2. Simulation Results

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, C.; Gao, Y.; Duan, E. The Influence of Environment on the Settlement of Historic Buildings in China. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 1951–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. Analysis of the Influence of Pile Foundation Settlement of High-Rise Buildings on Surrounding Buildings. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S. A Study of Differential Foundation Settlement of Piled Raft and Its Effect on the Long-term Vertical Shortening of Super-tall Buildings. Struct. Des. Tall Build. 2021, 30, e1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xu, J. Prediction of Buildings’ Settlement Induced by Metro Station Deep Foundation Pit Construction. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zeng, T.; Yuan, S.; Fan, H.; Xiang, W. Interval Prediction of Building Foundation Settlement Using Kernel Extreme Learning Machine. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 939772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimov, M.N. Settlement Stabilization of a Reconstructed Building. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2011, 47, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qu, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Investigating the Damage to Masonry Buildings During Shield Tunneling: A Case Study in Hohhot Metro. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 160, 108147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Influences of Deep Foundation Pit Excavation on the Stability of Adjacent Ancient Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotsenko, N.L.; Vinnikov, Y.L. Long-Term Settlement of Buildings Erected on Driven Cast-In-Situ Piles in Loess Soil. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2016, 53, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinin, V.I.; Sarana, E.P.; Soboleva, V.N.; Gurevich, D.V.; Katsnel’son, L.B. Engineering Analysis of Foundation Slab Settlement and Deformation for a High-Rise Building on a Nonuniform Rock Bed. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2016, 53, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Huang, F.; Wang, G.; Cui, T.; Cui, X.; Guo, F. Displacement Prediction of Inclined Existing Buildings with a Raft Foundation Restored by Compaction Grouting in Clay. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. On the Influence of Pile Foundation Settlement of Existing High-Rise Buildings on the Surrounding Buildings. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5560112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, R. A Parametric Study of Large Piled Raft Foundations on Clay Soil. Ocean Eng. 2022, 262, 112251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Debnath, B.; Reang, R.B.; Pal, S.K. Structural Analysis of Piled Raft Foundation in Soft Soil: An Experimental Simulation and Parametric Study with Numerical Method. Ocean Eng. 2022, 261, 112139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, H.; Fatahi, B. A Novel Cushioned Piled Raft Foundation to Protect Buildings Subjected to Normal Fault Rupture. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 106, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y. Settlement of Piled Raft Foundation Embedded in Rock and Its Calculation Method. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 41, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, X. Re-Analysis of Case Studies of Piled Raft Foundation for Super-Tall Building in Soft Soils. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 3253–3262+3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Hou, G.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, W. Settlement Characteristics and Calculation of Bending Moment for Large-Area Thick Raft Foundation Under Tall Buildings. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 36, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenbach, R.; Schmitt, A.; Turek, J. Assessing Settlement of High-Rise Structures by 3D Simulations. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2005, 2005, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Cause Investigation of Damages in Existing Building Adjacent to Foundation Pit in Construction. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 83, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fan, Q.; Qin, K. Influence of Karst Caves on the Pile’s Bearing Characteristics-A Numerical Study. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 754330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ding, H.; Zhang, P. Influence of Karst Caves at Pile Side on the Bearing Capacity of Super-Long Pile Foundation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 4895735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Geng, N.; Guo, P.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y. Bearing Behavior of Rock Socketed Pile in Limestone Stratum Embedded with a Karst Cavity beneath Pile Tip. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Lu, F.; Jiang, N.; Guo, P.; Li, X.; An, R.; Wang, Y. Bearing Behavior of Pile Foundation in Karst Region: Physical Model Test and Finite Element Analysis. Appl. Rheol. 2024, 34, 20230115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, C.; Huang, L.; Chen, W.; Lin, N.; Cui, J.; Xie, W. Performance of a Deep Excavation and the Influence on Adjacent Piles: A Case History in Karst Region Covered by Clay and Sand. Undergr. Space 2023, 8, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, P.; Hu, W.; Qiu, D. Seismic Response Analysis of Rock-Socketed Piles in Karst Areas Under Vertical Loads. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Xue, Y.; Li, Q.; Guo, B. Research on Bearing Capacity Characteristics of Cave Piles. Buildings 2025, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, D. Responses of Karst-Penetrating Piles Under Active and Passive Loading: Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 54, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Feng, Z.; Wu, M.; Zhou, G.; Chen, L.; Zhang, C. Study on the Vertical Bearing Performances of Piles on Karst Cave. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, D.; Prezzi, M.; Salgado, R.; Chakraborty, T. Settlement Analysis of Piles with Rectangular Cross Sections in Multi-Layered Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2008, 35, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, F.; Fenton, G.A.; Griffiths, D.V. Prediction of Pile Settlement in an Elastic Soil. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 60, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, X.; Wang, J. A New Nonlinear Method for Vertical Settlement Prediction of a Single Pile and Pile Groups in Layered Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2012, 45, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Xiao, K.; Cui, W. Settlement Calculation Method for the Solidified Soil Prefabricated Pile (PPSS) Embedded in Layer Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 179, 107053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, H.; Tian, Y.; Chen, H.; Hong, J. Research on Vertical Bearing Characteristics of Single Pile in Complex Interactive Karst Area. Buildings 2025, 15, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Xiao, L.; Zeng, C.; Mei, G. Innovative Flexible Casing for Concrete Loss Mitigation in Cast-in-Situ Piles: Karst Geological Case Study in Guizhou, China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 167, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB-50007-2011; Code for Design of Building Foundation. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Crispin, J.J.; Leahy, C.P.; Mylonakis, G. Winkler Model for Axially Loaded Piles in Inhomogeneous Soil. Géotechnique Lett. 2018, 8, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elastic Modulus E (MPa) | Density γ (kN/m3) | Friction Angle φ (°) | Cohesion c (kPa) | Poisson’s Ratio μ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miscellaneous Fill | 3 | 1500 | 10 | 10 | 0.40 |

| Plastic Red Clay | 5.3 | 1800 | 10 | 35 | 0.35 |

| Soft Plastic Red Clay | 0.5 | 2000 | 3 | 15 | 0.33 |

| Bedrock | 500 | 2300 | 40 | 800 | 0.30 |

| Concrete | 30,000,000 | 2500 | - | - | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, X. Urban High-Rise Building Asymmetric Settlement Induced by Subsurface Geological Anomalies: A Case Analysis of Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122068

Cui X. Urban High-Rise Building Asymmetric Settlement Induced by Subsurface Geological Anomalies: A Case Analysis of Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122068

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Xuedong. 2025. "Urban High-Rise Building Asymmetric Settlement Induced by Subsurface Geological Anomalies: A Case Analysis of Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122068

APA StyleCui, X. (2025). Urban High-Rise Building Asymmetric Settlement Induced by Subsurface Geological Anomalies: A Case Analysis of Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. Symmetry, 17(12), 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122068