1. Introduction

Hyperspectral images (HSIs) are captured through continuous narrow-band imaging, enabling the acquisition of fine spectral characteristics of target objects. Compared to grayscale and RGB images, HSIs can more comprehensively reflect the spectral information and spatial distribution of target areas, making them widely applicable in environmental monitoring, agriculture, military reconnaissance, and other fields [

1,

2,

3]. HSIs usually have high resolution, large width, and rich geospatial information, and they are suitable for tasks such as image classification [

4], target segmentation [

5], target detection [

6], and super-resolution [

7]. Recent years have witnessed significant advances in deep learning and artificial intelligence within the field of hyperspectral imaging. Techniques such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), self-supervised learning, and Transformer-based models have substantially improved performance in tasks including classification, anomaly detection, and target detection. These AI-driven methodologies are increasingly exploring their generalization capabilities across different tasks, domains, and sensor types, thereby paving new technical pathways toward scalable, automated, and robust hyperspectral analysis workflows [

8]. However, their enormous data volume poses significant challenges for transmission and storage in on-orbit remote sensing satellites and end-user applications. To achieve high fidelity and better preserve the spectral information of HSIs, efficient H compression techniques have become a key research focus.

Traditional 2D image coding employs a hybrid coding framework composed of modules such as prediction, transform, quantization, and entropy coding. Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) are widely used in conventional transform coding techniques to decompose the original image into energy-concentrated coefficients, which are then quantized to achieve efficient compression. For example, the classic image coding standard JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group) [

9] applies DCT to 8 × 8 image blocks, but this approach introduces severe blocking artifacts under low-bitrate conditions. JPEG2000 [

10] adopts DWT, supporting input blocks of arbitrary sizes and significantly mitigating blocking artifacts.

Recently, deep learning-based lossy image processing has achieved better performance than traditional approaches [

11,

12]. For instance, Toderici et al. [

13,

14] utilized Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to progressively generate entropy-coded bitstreams and intermediate reconstructed images of varying quality, adjusting the compression ratio by controlling the number of iterations. Jiao et al. [

15] employed Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to reduce artifacts generated by the JPEG standard when compressing holographic images, addressing quality degradation caused by the loss of high-frequency features during compression. Kingma et al. [

16] introduced Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), while Ballé et al. [

17] enhanced the original VAE framework by incorporating an entropy model and a hyperprior structure. Minnen et al. [

18] further advanced the field by introducing an autoregressive model. Cheng et al. [

19] significantly improved compression efficiency by integrating residual blocks, a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)-based entropy model, and attention mechanisms. Minnen et al. [

20] proposed a channel-wise autoregressive entropy model, further enhancing the performance of learned image compression algorithms. Currently, end-to-end learned image coding techniques fully demonstrate their potential in leveraging spatial correlations and statistical distributions of images, achieving optimized rate-distortion trade-offs while allowing rapid adjustment of various distortion metrics.

With the generation of HSI data, compression methods tailored for HSIs have been extensively studied, resulting in numerous research efforts [

21]. The focus lies in designing effective feature extractors and entropy coders. In recent years, to address the urgent demand for HSI compression, the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) established and released the low-complexity lossless and near-lossless multispectral/hyperspectral image compression standard CCSDS123.0-B-2 [

21] in 2019 (hereinafter referred to as CCSDS123.0-B-2). This new standard extends the capabilities of its predecessor, CCSDS123.0-B-1 [

21], which only supported lossless compression. Here, ‘near-lossless’ refers to the ability to perform compression in a way that the maximum error in the reconstructed image can be limited to a user-specified bound. CCSDS123.0-B-2 improves the predictor by introducing error constraints, enabling near-lossless compression. Additionally, it incorporates a novel entropy coding method called Hybrid Entropy Coding to enhance compression efficiency for low-entropy data.

Meanwhile, learning-based HSI compression methods have also advanced rapidly. Guo [

22] proposed HCCNet, a hyperspectral compression network leveraging cross-channel contrastive learning. Zhang [

23] adopted a compressed sensing approach, introducing a CNN–Transformer hybrid architecture for HSI compression. Rezasoltani [

24] developed a compression method based on Implicit Neural Representation (INR). Zhang [

25] proposed a low-overhead, compressed sensing-based channel filtering method, where the encoder derives channel filters via least-squares regression between the compressed and original images, transmitting a bitstream containing both the compressed image and filters to the decoder.

Although existing methods have achieved certain progress, HSI compression still faces numerous challenges. Traditional approaches such as JPEG2000 [

10] and CCSDS123.0-B-2 exhibit a significant degradation in reconstructed image quality at low bit rates, while direct application of visible-light image compression models leads to the loss of spectral characteristics. Most current deep learning-based HSI compression methods adopt compressed sensing frameworks, which generate code streams without entropy encoding modules and are thus unsuitable for transmission over satellite communication channels. Therefore, investigating HSI compression models incorporating entropy encoding is of great importance for reducing the data transmission burden in satellite systems.

The data characteristics of HSIs dictate the design rationale for their compression frameworks. The spatial dimension of an HSI contains rich textural and structural information, while the spectral dimension records the unique spectral response curves of ground objects. These two types of information are closely interrelated yet distinct: abrupt changes in spatial details often correspond to rapid variations in spectral features, whereas smooth regions exhibit high inter-spectral correlation. Existing methods, such as those directly adapted from visible-light image models, typically employ uniform 2D convolution operations. This approach struggles to adaptively balance the utilization efficiency of spatial and spectral information, often resulting in either blurred spatial details or distorted spectral characteristics under constrained bitrates. Therefore, the primary motivation of this work is to design a mechanism capable of explicitly and separately extracting spatial and spectral features, aiming to maximize the preservation of critical information in each dimension through dedicated feature extraction pathways.

However, processing spatial and spectral features in isolation is insufficient for achieving optimal compression. The essence of an HSI lies in its representation of a spatial scene projected across a continuous spectral range, with both dimensions unified at a semantic level. If spatial and spectral features are separated during encoding, the decoder will face challenges in reconstructing this intrinsic coherence. Thus, feature fusion becomes a critical step. This paper introduces a spatial–spectral joint encoding–decoding network, where independently extracted features are fused in the latent space. This enables the model to learn the mapping relationships between spatial structures and spectral curves, thereby leveraging the fused features during decoding to reconstruct the image with higher accuracy.

During the feature fusion and reconstruction process, the contribution of different spatial locations and spectral bands to the overall reconstruction quality is not uniform. For instance, spatial details in edge regions typically carry higher information content and warrant a greater allocation of bits. Existing compression frameworks often lack the capability to model such non-uniform importance, leading to inefficient bitrate allocation. To address this key limitation of undifferentiated bit distribution, this work incorporates an attention mechanism. The attention module dynamically computes weights for spatial–spectral features, guiding the model to prioritize the allocation of limited bits to information-intensive regions and bands. Consequently, under the same bitrate, the proposed approach achieves higher reconstruction fidelity, particularly by suppressing overall distortion under low-bitrate conditions.

In light of the correlated yet distinct spatial and spectral characteristics of hyperspectral imagery, this paper proposes an end-to-end lossy compression model based on joint spatial–spectral feature extraction and attention mechanisms. The model employs a variational autoencoder (VAE) architecture to separately extract and fuse spatial and spectral features for encoding and decoding, thereby achieving end-to-end compression of HSIs. Building upon visible-light image compression models, spectral features are extracted using 3D convolutions and fused with features obtained through 2D convolutions. The latent representation of the image is derived via analysis transformation, quantized, and subsequently entropy-encoded using a channel-wise autoregressive entropy model to generate a transmission-friendly bitstream. This bitstream is then synthesized through inverse transformation and reconstructed into the original HSI via a joint spatial–spectral feature recovery module. The structures of the joint feature extraction and recovery modules are symmetric. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through comparisons with state-of-the-art HSI compression standard algorithms.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 1, the Introduction, outlines the characteristics of HSIs, traditional image compression methods, and deep learning-based hyperspectral compression techniques. It also discusses the limitations of existing approaches and provides a brief overview of the proposed model architecture.

Section 2 reviews the main development of lossy compression methods for HSIs based on deep learning.

Section 3 elaborates on the structure of the end-to-end HSI compression model based on joint spatial–spectral feature extraction and attention mechanisms, detailing the spatial information extraction module, spectral information extraction module, spatial–spectral feature fusion-based encoding–decoding network, and the local attention mechanism.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup and evaluation methodology.

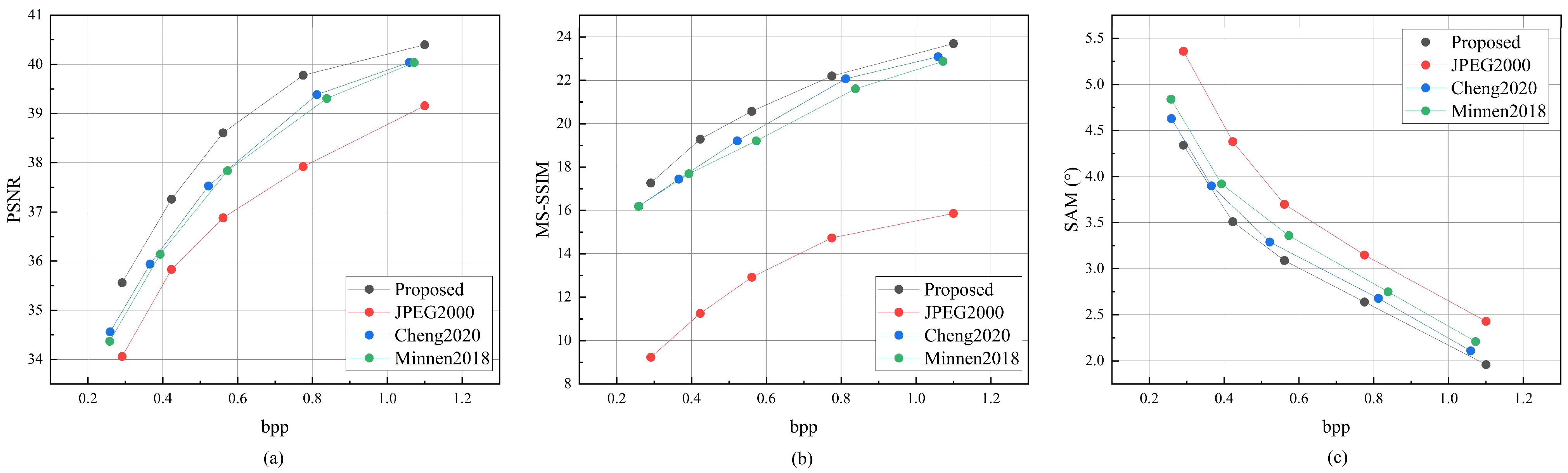

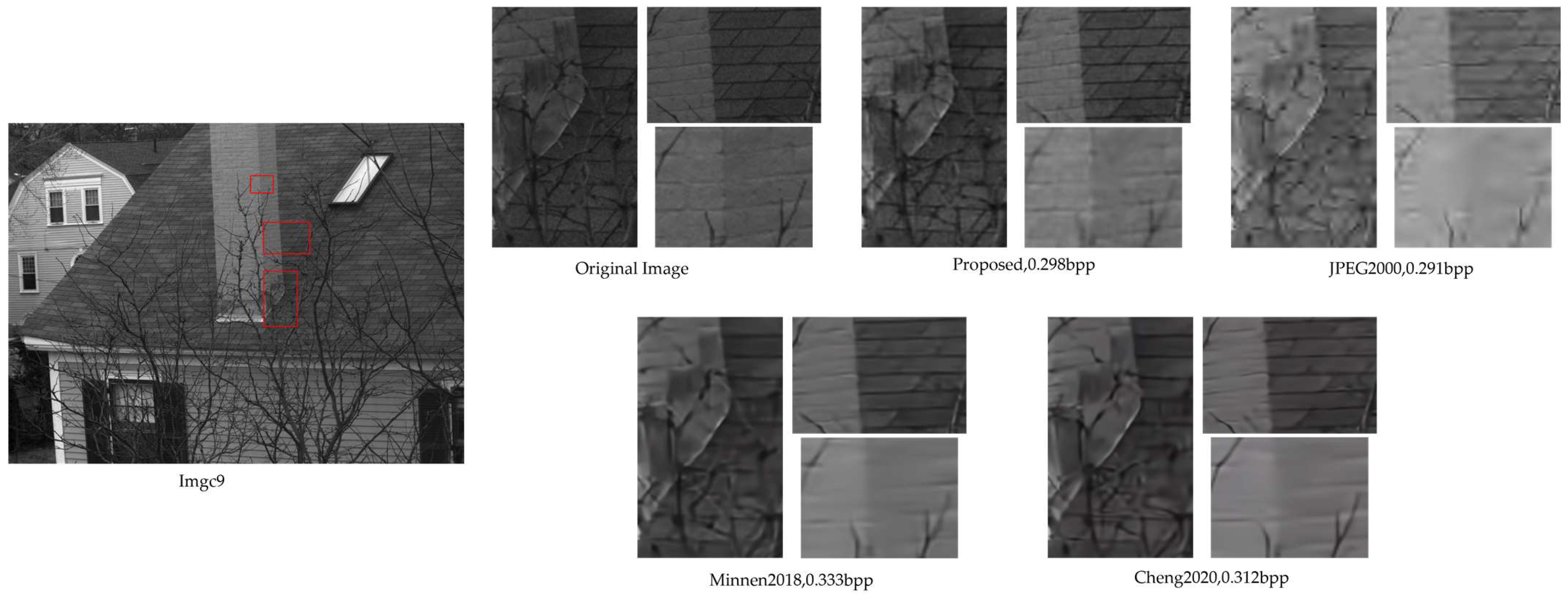

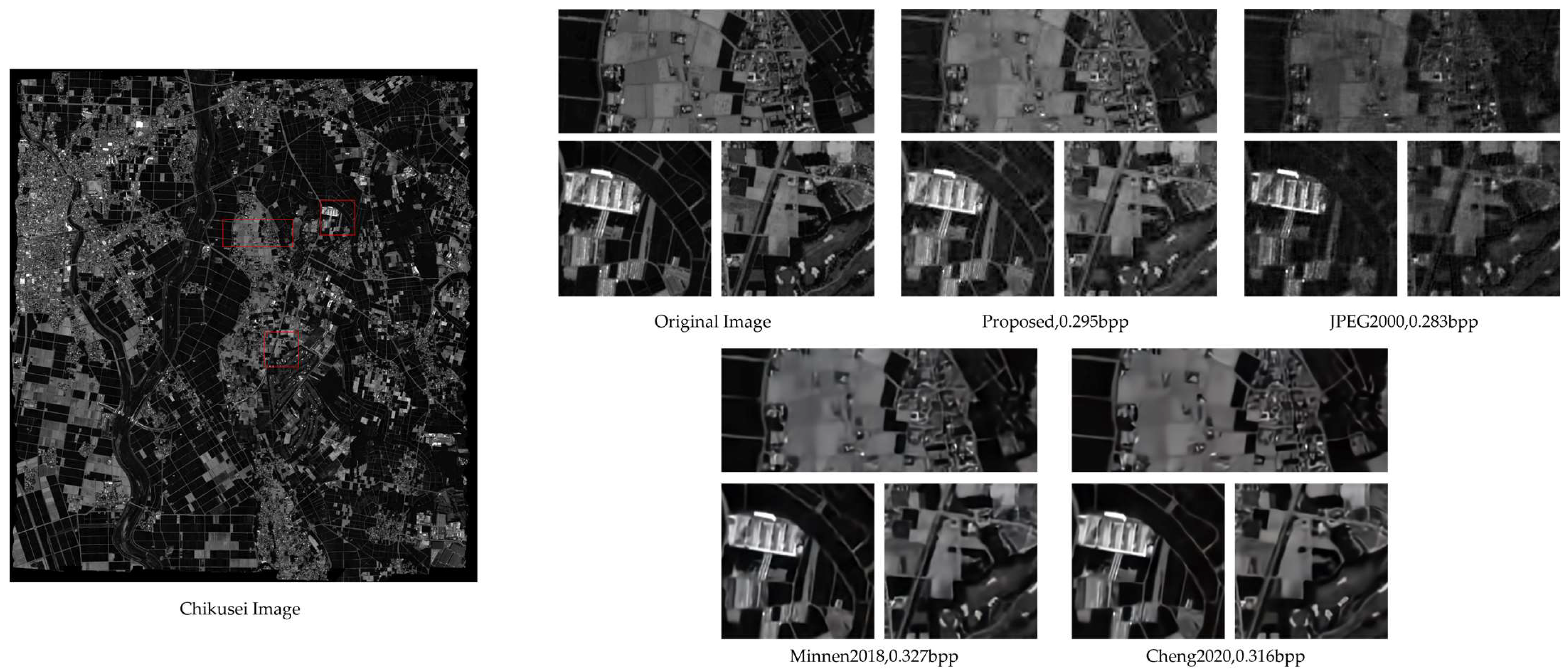

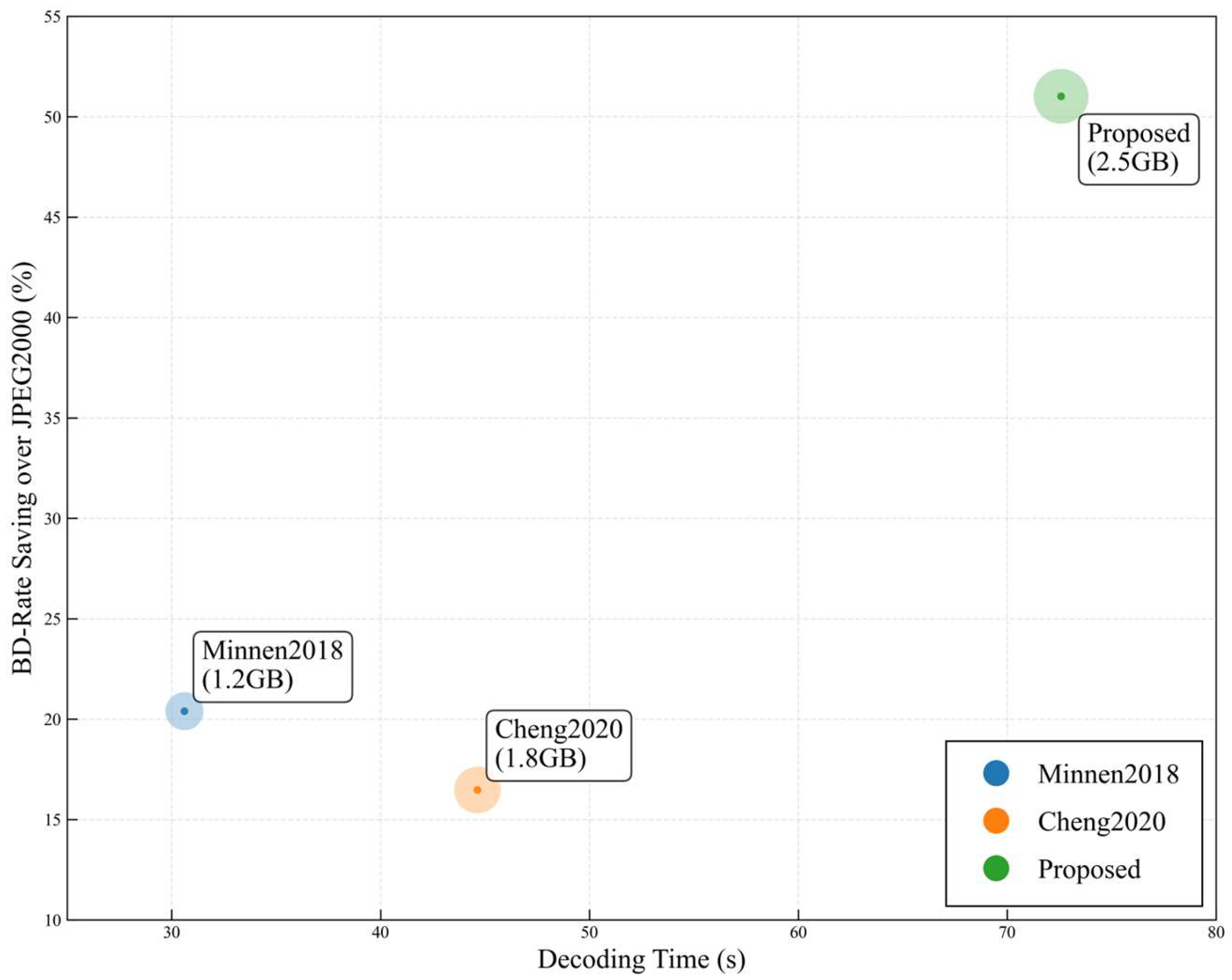

Section 5 presents an analysis of the rate-distortion performance of the proposed method, comparing it with traditional approaches and two deep learning-based visible-light image compression models. Reconstructed image details are visually demonstrated, and the results are thoroughly discussed.

2. Related Work

Early HSI compression methods typically applied RGB image compression techniques to encode HSI data in a band-by-band manner. This approach fails to exploit inter-spectral correlations, resulting in suboptimal rate-distortion performance. To address this limitation, several studies [

26,

27] have extended two-dimensional image compression algorithms to handle the three-dimensional nature of HSIs. These methods often employ transform coding, which converts HSIs from the pixel domain into a latent space (e.g., frequency domain). Prominent transforms, such as the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) and wavelet transforms, utilize linear operations typically defined by a set of linear and orthogonal basis functions. However, such linear transforms with fixed bases may not fully capture the underlying redundancies, as HSIs are not generated by a linear combination of independent components [

28]. Consequently, nonlinear transforms may be more suitable for HSI compression.

In recent years, learning-based nonlinear transforms [

29,

30] have demonstrated considerable potential in HSI compression. Dua et al. [

29] and La et al. [

30] were among the first to introduce autoencoder (AE) for lossy HSI compression. Subsequently, the variational autoencoder (VAE), which incorporates variational Bayesian theory, has been adopted to represent the latent features of input HSIs from a probabilistic perspective. Owing to its ability to effectively model image statistics, the VAE framework has emerged as a dominant architecture in image compression. Building upon the VAE, Guo et al. [

31] utilized a hyperprior model [

17] to compress HSIs. Guo [

22] further proposed HCCNet, a hyperspectral compression network incorporating cross-channel contrastive learning, to better preserve spectral characteristics.

To fully leverage inter-spectral correlations and achieve superior rate-distortion performance, the proposed HSI compression method adopts a variational autoencoder architecture. It integrates both 2D and 3D convolutional layers to jointly model spatial and spectral features, and incorporates an attention mechanism to enhance reconstruction detail and rate-distortion optimization.

3. Method

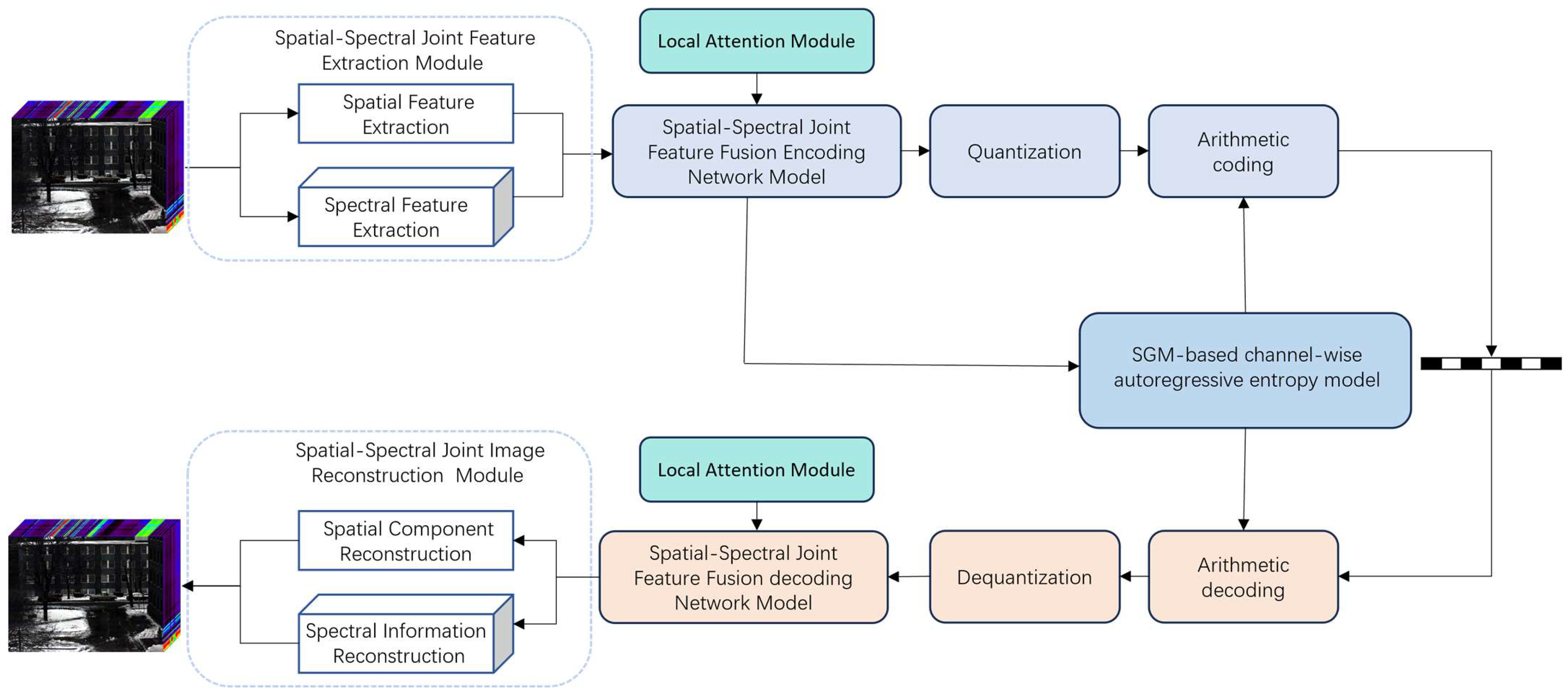

The overall framework of the proposed end-to-end HSI compression network, which integrates spatial–spectral joint feature extraction with attention mechanisms, is illustrated in

Figure 1. The encoding process first feeds the input HSI into a spatial–spectral joint feature extraction network to separately extract spectral features and spatial features, which are then concatenated to form complete joint spatial–spectral feature information. The joint spatial–spectral feature data is subsequently input into a feature fusion encoding network to generate low-dimensional feature representations. Finally, the low-dimensional feature representations are quantized. The potential probability distribution of the low-dimensional features is predicted through the single Gaussian distribution-based channel-wise autoregressive entropy model (SGM-based channel-wise autoregressive entropy model) [

20], and the arithmetic coding is used to generate the binary code stream.

The decoding reconstruction process performs inverse operations of the encoding stage. The decoder first reconstructs the low-dimensional feature representations from the compressed binary bitstream through arithmetic decoding and inverse quantization. These recovered low-dimensional feature representations are then fed into a feature fusion decoding network to restore the joint spatial–spectral features. Ultimately, the HSI is reconstructed by the spatial–spectral joint image reconstruction network.

This algorithm specifically addresses the characteristics of HSI by proposing a novel compression approach based on spatial–spectral information extraction. This method extracts spatial information and spectral information respectively and fuses them, and then it inputs the fused information into the fusion coding network to more effectively eliminate redundancy. During the decoding process, it reconstructs the spatial and spectral components to achieve high-quality image restoration.

3.1. 3D-2D Hybrid Convolution-Based Spatial–Spectral Joint Feature Extraction Module

3.1.1. Spatial Feature Extraction Module

Spatial information constitutes the primary input received by the human visual system and holds particular significance in the field of image processing. Similar to visible light images, HSIs also contain substantial spatial information. With continuous improvements in spectral imaging resolution, the spatial information in acquired images has become increasingly abundant. During HSI compression, it is crucial to eliminate spatial redundancies while preserving critical features.

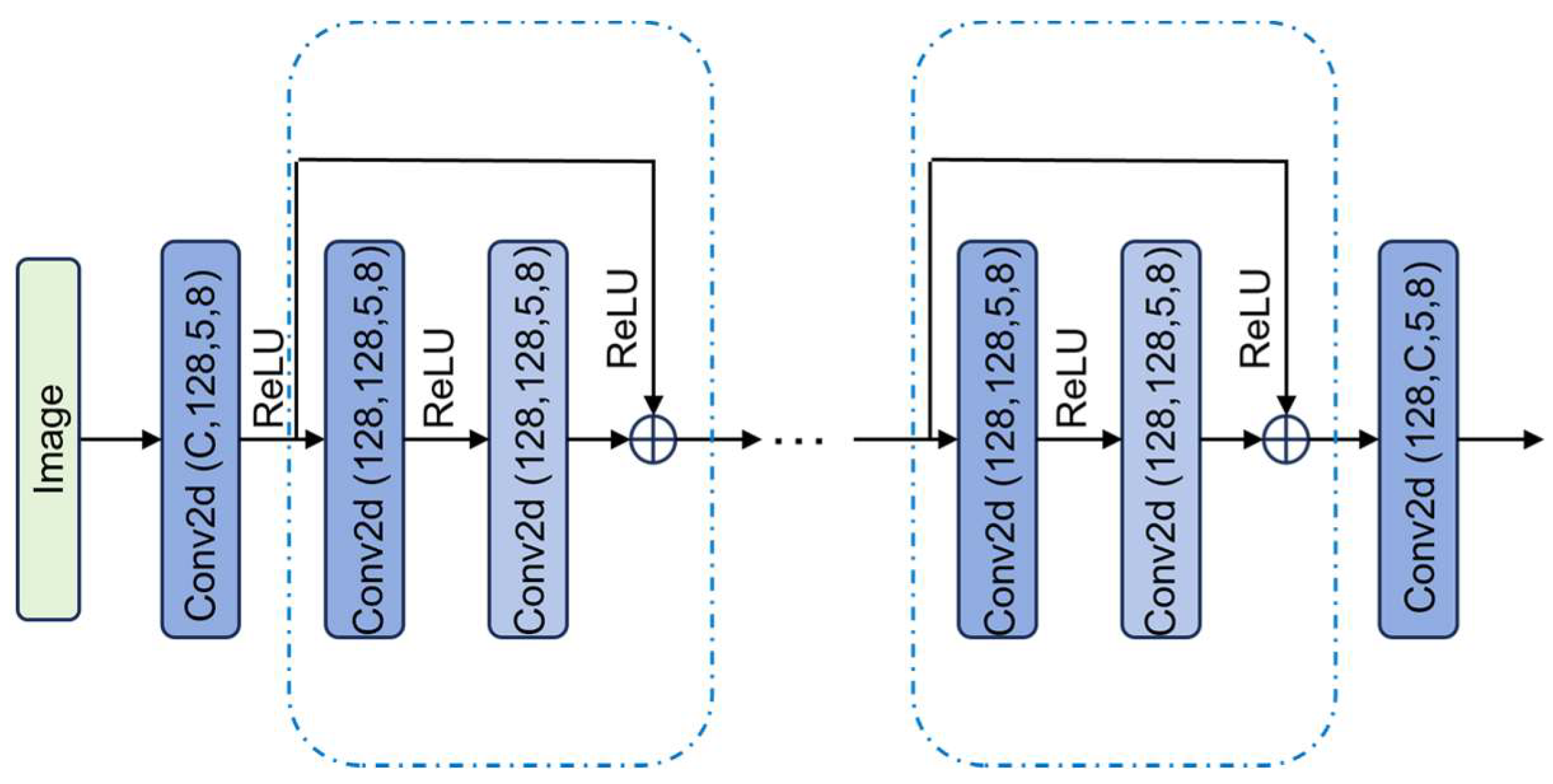

This section proposes a spatial feature extraction module based on the residual network architecture in CNN. When extracting spatial features directly using CNN, the naive approach would cause unintended fusion of information across spectral bands, thereby interfering with spectral feature extraction. To address this limitation, we employ grouped convolution for feature extraction. The detailed architecture is illustrated in

Figure 2, where Conv() represents grouped convolution. All parameters remain consistent with conventional convolution except for the final parameter, which specifies the number of groups.

To accelerate feature extraction and mitigate issues such as gradient vanishing or explosion, the fundamental unit of the spatial feature extraction module adopts a two-layer residual block structure. The processing pipeline operates as follows: First, the HSI data is fed into an initial grouped convolutional layer. While this layer maintains the same number of convolutional kernels as conventional convolution, it significantly reduces computational overhead by restricting each kernel’s operation to only within its assigned feature group during the extraction process.

3.1.2. Spectral Feature Extraction Module

In addition to spatial information, HSIs contain substantial spectral information with significant inter-band redundancies that must be effectively removed during compression. To better eliminate these spectral redundancies, this section proposes a dedicated Spectral Feature Extraction Module specifically designed to extract inter-band spectral characteristics.

Similar to the spatial feature extraction module, the spectral feature extraction module is designed to exclusively process inter-band information to maintain spectral integrity while maximizing redundancy elimination, deliberately avoiding fusion with spatial features. Three-dimensional (3D) convolution extends traditional two-dimensional (2D) convolution by incorporating an additional data dimension, making it particularly suitable for processing multi-frame image data in applications such as video analysis and medical imaging.

For HSIs containing multiple spectral bands, the data can be conceptually represented in two ways: as a single-frame image with multiple channels (where channels correspond to spectral bands) or as a multi-frame sequence with a single channel (where frames represent spectral bands). To facilitate effective spectral feature extraction using 3D convolution, we adopt the latter representation, treating each spectral band as an individual frame in a single-channel sequence.

In standard implementation, 3D convolution kernels operate by sliding across all three dimensions of the input data, introducing an additional depth-wise convolution process compared to 2D convolution. The computational complexity can be quantified as follows: for 2D convolution, the computation scales as , while for 3D convolution it increases to , where represents the number of spectral bands, denotes the kernel size, and indicate spatial width and height respectively, and corresponds to the spectral dimension (analogous to the temporal dimension in video processing). This formulation demonstrates that 3D convolution incurs significantly higher computational overhead compared to its 2D counterpart.

Direct application of 3D convolution for HSI feature extraction would not only incur substantial computational overhead but also lead to unintended fusion of spatial and spectral information during feature extraction. To mitigate computational complexity while exclusively extracting inter-band spectral features, we strategically configure the 3D convolution kernel dimensions: employing 1 × 1 kernel size in spatial dimensions (effectively disabling spatial feature extraction) while maintaining a kernel size of 3 along the spectral dimension. This modified implementation restricts feature extraction solely to inter-band correlations while significantly reducing parameter computations, with the computational complexity now expressed as . Compared to conventional 3D convolution, this approach achieves a -fold reduction in parameter count while preserving dedicated spectral information extraction.

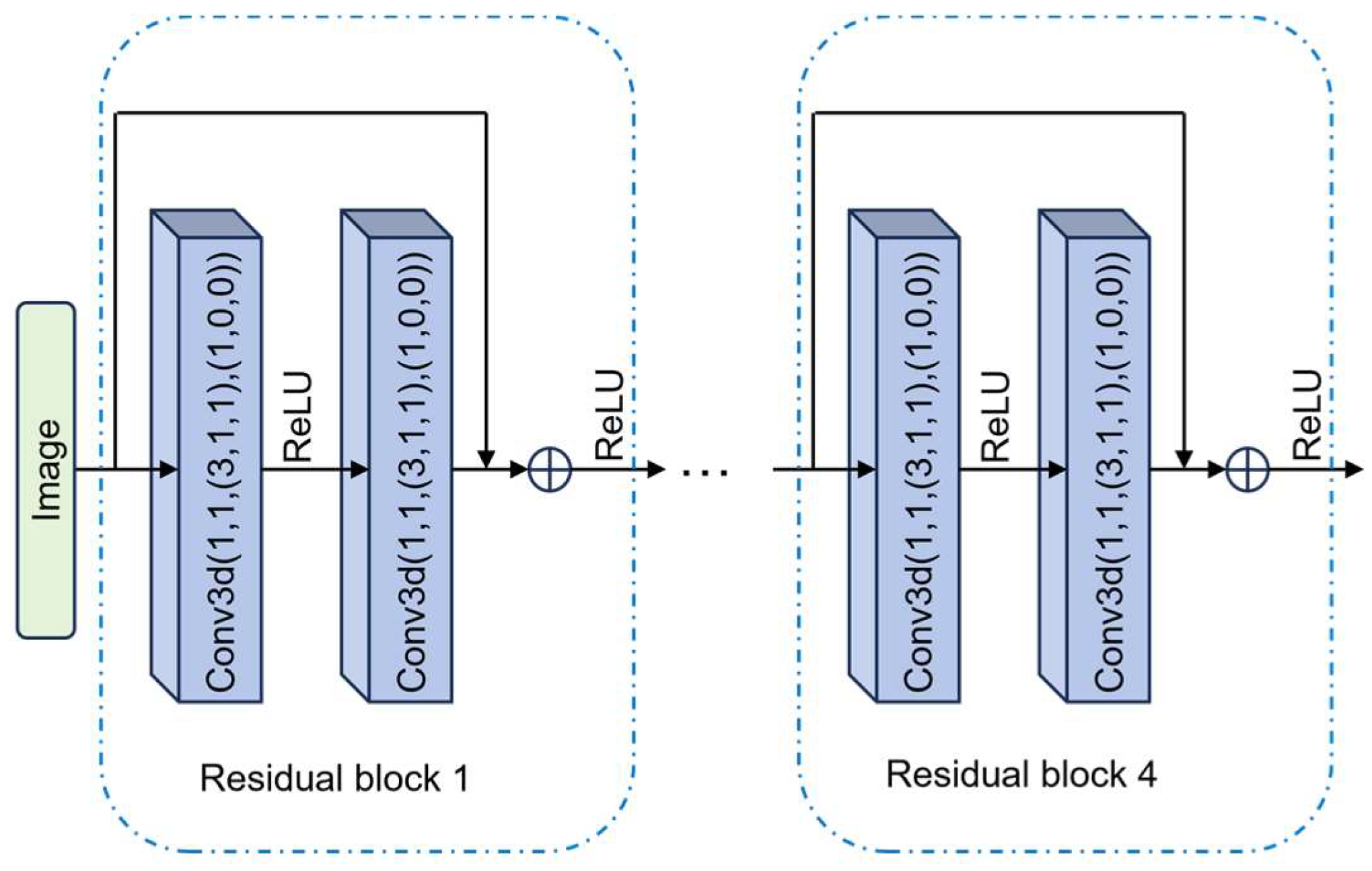

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the spectral feature extraction module architecture processes hyperspectral data through the following stages: First, the input HSI is transformed into a single-channel multi-frame representation, where the frame count corresponds to the number of spectral bands. This restructured data then passes through a series of two-layer residual blocks composed of our modified 3D convolutions. Multiple residual blocks progressively extract hierarchical spectral features while maintaining spectral purity. Finally, the processed feature maps are reshaped to their original dimensions for subsequent fusion with parallel-extracted spatial features. Notably, all convolution kernels maintain three-dimensional parameters (one spectral dimension and two spatial dimensions), though spatial feature extraction is deliberately suppressed through the 1 × 1 spatial kernel configuration. This design ensures exclusive spectral information flow while maintaining compatibility with spatial feature fusion at later network stages.

3.2. Spatial–Spectral Joint Feature Fusion Encoding–Decoding Network Model

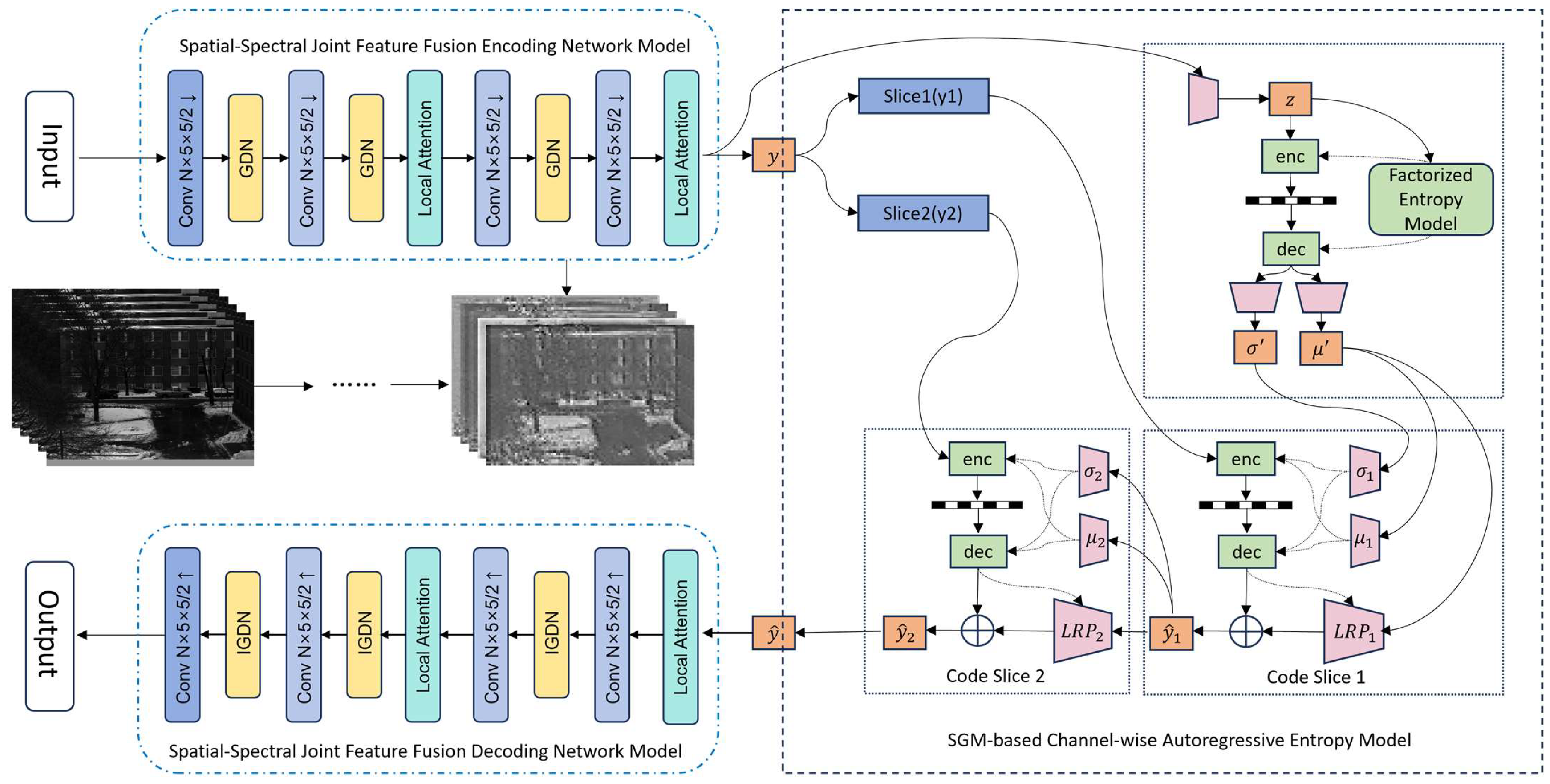

Inspired by end-to-end compression models for visible light images, our framework employs a hybrid 2D-3D convolutional architecture to extract joint spatial–spectral features, which are then processed through a dedicated spatial–spectral feature fusion encoding–decoding network. To enhance the model’s capability in learning complex information relationships, we incorporate a local attention mechanism. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the proposed spatial–spectral fusion encoding/decoding network comprises three core modules: spatial–spectral feature fusion encoding network, spatial–spectral feature fusion decoding network and arithmetic encoding/decoding components.

The spatial–spectral feature fusion encoding network processes the input hyperspectral image’s joint spatial–spectral features through a series of convolutional downsampling modules, Generalized Divisive Normalization (GDN) layers [

32], and local attention mechanisms to achieve effective feature fusion. The resulting low-dimensional compressed representation preserves the majority of the original hyperspectral image’s critical information while significantly reducing redundancy.

Our proposed method builds upon the hyperprior architecture [

17,

18] and channel-wise autoregressive entropy model [

20]. The encoder

transforms a given input image

into a latent representation

. After quantization

,

denotes the discrete-valued latent representation of

. The decoder

subsequently reconstructs the output image

from

. This primary workflow can be formally expressed as:

where

and

are trainable parameters of the encoder

and decoder

. Quantization

inevitably introduces clipping errors of the latent (

), which leads to distortion of the reconstructed image. Following previous work [

20], in the training phase, we also modify the quantization error by rounding and adding the predicted quantization error.

We model each element

as a single Gaussian distribution with its standard deviation

and mean

by introducing a side information

. The distribution

of

is modeled by a single gaussian distribution-based entropy model (SGM):

The loss function of image compression model is:

where

controls the trade-off between rate and distortion,

is the bit rate of latents

and

,

is the distortion between the raw image

and reconstructed image

.

The encoding network incorporates Generalized Divisive Normalization (GDN), which serves as a divisive normalization module. GDN represents one of the most widely used normalization and nonlinear activation functions in image compression. In the decoding network, Inverse GDN (IGDN) performs the inverse operation of GDN in the encoding pathway. Within both the spatial–spectral feature fusion encoding and decoding networks, we introduce a local attention mechanism that assigns higher weighting coefficients to image feature regions with high contrast during the fusion encoding/decoding process, followed by fusion encoding/decoding of the re-weighted features.

The decoder network performs inverse operations corresponding to the encoder network, utilizing convolutional upsampling modules, IGDN, and local attention modules to reconstruct the spatial–spectral features of the HSI.

HSI compression aims to reconstruct high-quality images at given bitrates, where establishing an accurate entropy model is crucial for bitrate estimation. Therefore, the proposed network architecture introduces an SGM-based channel-wise autoregressive entropy model [

20] to predict the latent probability distribution of the low-dimensional features output by the encoding network. The learned parameters are then transmitted to both the arithmetic encoder and decoder for entropy encoding and decoding operations.

3.3. Local Attention Mechanism

The attention mechanism computationally emulates biological perceptual processes by selectively allocating cognitive resources to salient regions, thereby enhancing detail acquisition while suppressing irrelevant information. This paradigm mirrors neurobiological attention mechanisms wherein distinct spatial regions receive differential processing priority based on their behavioral relevance. Specifically, the system dynamically modulates its information processing capacity to preferentially encode and retain high-value visual features in regions of interest (ROIs), while attenuating neural responses to less significant areas.

The network training process involves learning hierarchical representations of image data through the optimization of feature-specific weighting parameters via backpropagation. These learned weights are applied through element-wise multiplication with the original input features to generate enhanced feature maps.

In the network training process, the generation of attention masks based on spatially adjacent elements can effectively enhance the rate-distortion performance of the network at a relatively low computational cost. To improve the quality of reconstructed images, inspired by the Non-Local Attention Module (NLAM) [

33], this section introduces a local attention module into the network architecture. This module specifically focuses on regions with complex texture features by partitioning the feature map into non-overlapping blocks and independently computing attention maps for each block.

Here, and represent the i-th and j-th elements within the k-th partitioned block, respectively. The function denotes an embedded Gaussian function, which computes the similarity between elements, while serves as a normalization factor to ensure the attention weights sum to unity. Additionally, corresponds to the embedding matrix associated with the spatial position of the k-th block, enabling location-aware feature transformation.

The attention map for each block is obtained by incorporating residual connections to the intra-block attention computation, as formalized in Equation (6):

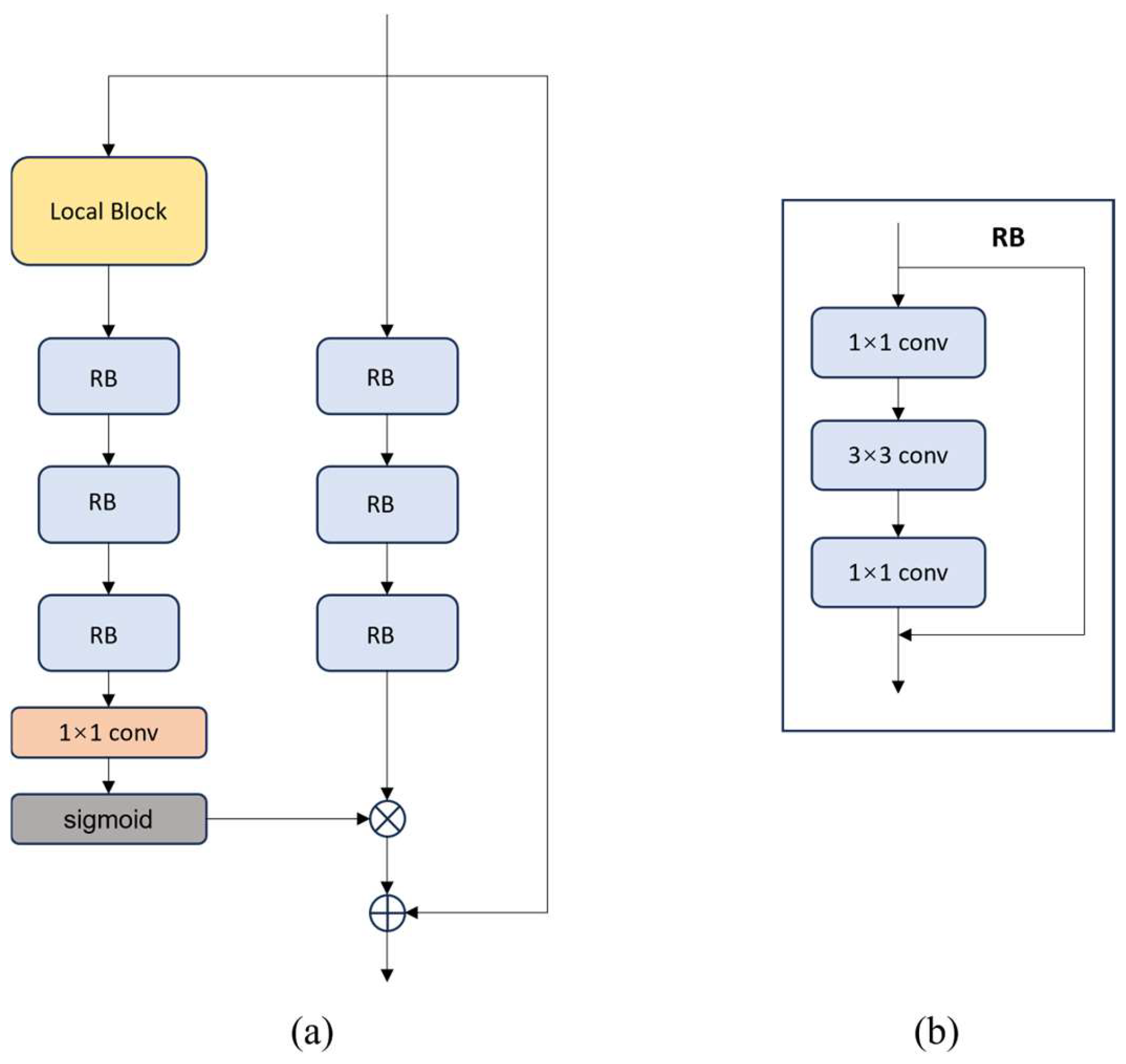

Based on the computational results, regions with significant information divergence in the image are identified, and additional bit allocation is assigned to these complex information areas. The structure of the local attention module is illustrated in

Figure 5a, where the residual block consists of convolutional layers composed of 1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolutions, as shown in

Figure 5b.

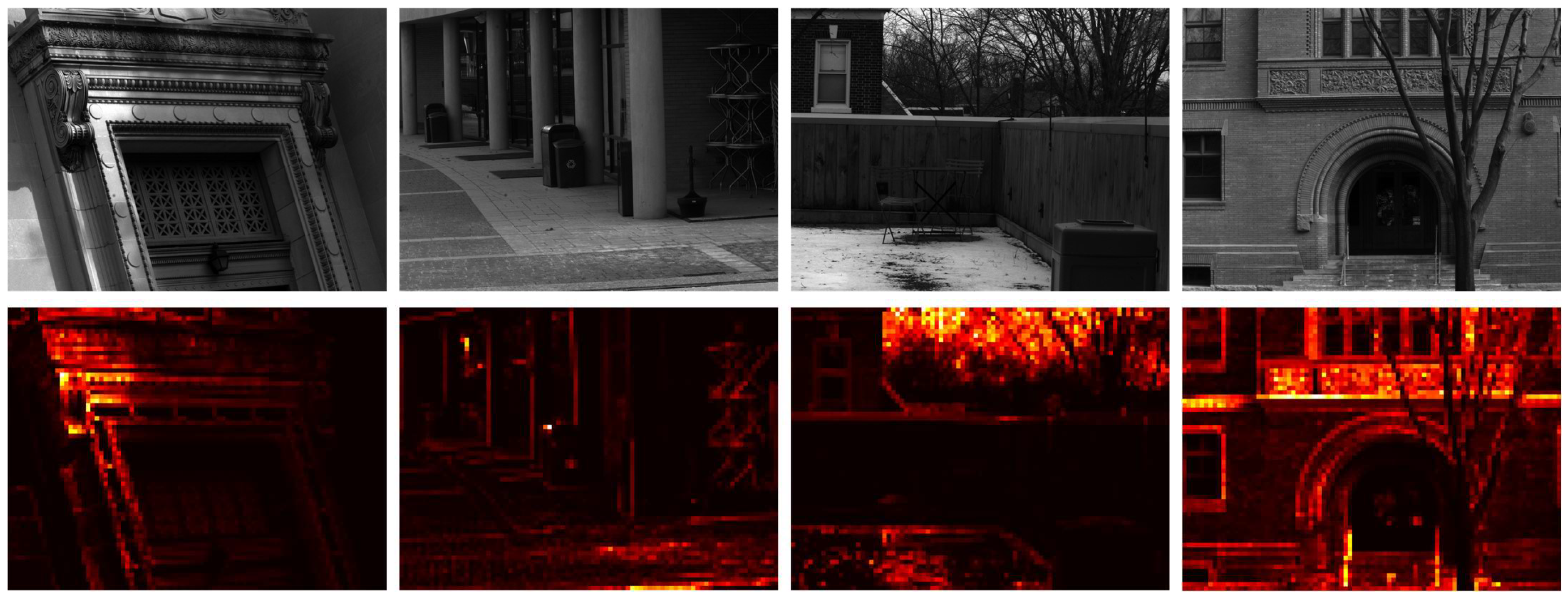

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the feature maps generated by the attention module reveal its operational mechanism: it effectively guides the bit allocation strategy. Significantly more bits are assigned to detail-rich regions, such as the textured patterns on the wall, thereby preserving fine spatial information. Fewer bits are allocated to the relatively smooth wall areas in the image, which indicates the significant role of the attention module in the feature map.