1. Introduction

Turbulence in Newtonian fluids is certainly one of the oldest problems in out-of-equilibrium physics that is still today under active investigation. One of the biggest breakthroughs in its study has certainly been the work of Kolmogorov in 1941 [

1,

2,

3], who has shown that, although the motion of the turbulent fluid seems erratic, there exists some universally quantifiable regularity in the behaviour of some of its statistical properties, like the velocity pair correlation function, at least under some assumptions of isotropy, average homogeneity, and, more crucially, incompressibility of the fluid.

The case of compressible fluids though, is also of great importance in various fields of physics, mostly for applications in aeronautics, but also in astrophysics as it is the basis of models of the interstellar medium, the generation of galaxies and stars and their evolution through time. The scaling of statistical characteristics of compressible fluids however remains still largely elusive today, as witnessed by evaluations of the situation in relatively recent papers: “the theoretical understanding of compressible turbulence is still poor” [

4], “To our knowledge, no universal law has been derived for compressible turbulence” [

5], or “The particle distribution function and spectrum is still a matter of debate” [

6].

Most of the studies of the subject have been conducted numerically. They do not yield a clear and consistent picture of how compressible fluids behave in turbulent flows. It is to be noted that, over the years, numerical methods have evolved, which surely explains part of the dispersion of results. There are also two types of limitations that are intrinsic to numerical simulations that can explain at least partly the discrepancies with the theoretical results—exposed hereafter—first the fact that simulations are conducted on the Euler equation, and, thus, the viscosity is generated numerically rather than given as a physical input in the equations of motion, and second the so-called bottleneck effect that reduces the effective size of the inertial range in which universal behaviors are to be expected [

6].

Without being exhaustive, the recent numerical results regarding the scaling laws of compressible turbulence can be summarized as follows: In [

7], it is revealed that the statistical characteristics of the flows stay similar to those of incompressible fluids for Mach numbers Ma ≲ 1. Then, the study conducted for Ma = 6 regarding the scaling of the power law exponent of the kinetic energy spectrum

yields

, in contrast to the

value predicted by Kolmogorov in the incompressible case (hereafter denoted K41 scaling for short). The density of the fluid is predicted to scale as

.

In [

8], the influence of the type of forcing on supersonic flows is examined; in particular, the extreme limits of purely solenoidal or purely compressible forcings are investigated. It is then shown that the dependence on the type of forcing is strongly reduced if one studies the evolution of the mass-weighted velocity

instead of the velocity

. In a following paper [

4], it is shown that this effect is exacerbated if the Eulerian framework is used in contrast to the Lagrangian one, at least for Mach numbers in the range Ma ∼ 4.4–4.9. A subsequent study [

6], conducted at higher Mach numbers (Ma = 17), computes more precisely the values of the scaling exponents in the case of the mass-weighted velocity distribution function. In particular, they report two exponents

for the case of solenoidal driving and

in the case of compressible driving, showing a behavior closer to that of the one-dimensional (1D) Burgers’ fluid where

(and very close to the theoretical prediction of [

5] presented below). In agreement with the above, the incompressible K41 scaling is recovered for Ma ≲ 1.

Then, in the group of J. Wang and their collaborators, two studies at moderate Mach numbers have concluded first that the overall exponent

[

9], in agreement with the 1D Burgers’ prediction, and, in a refined study [

10] showing that, in the non linear subsonic regime 0.5 < Ma < 1, the velocity increment can be split into one positive component with 1D Burgers scaling, and a negative component with K41 scaling. On the other hand [

11] concluded the same year that for Ma ≳ 0.3, corrections to the 1D Burgers scaling are to be expected. The study gives explicit expressions for these corrections.

Finally [

12] concluded after an analysis of a large database of direct numerical simulation (DNS) of the compressible Navier–Stokes equations that the Reynolds number Re and Ma were not sufficient to characterize correctly the scaling properties of the fluid, since the data comprising different geometries and types of forcing do not collapse well onto one master curve. They propose instead to use

, the ratio of the root mean square parts of the incompressible and compressible parts of the velocity vector together with Ma. They show a good collapse of all the data of the ratio of the incompressible to the compressible mean kinetic energy dissipation rate as a function of

on a single straight line, which is an indication that Prandtl’s Misschungsweghypothese [

13] holds also for compressible fluids. As Ma increases,

converges towards a finite value

, a result in qualitative agreement with previous theoretical results exposed in [

14,

15]. Quantitative agreement between all these approaches is not reached however, probably because of a remaining lack of precision.

On the theoretical side, one of the first studies is probably that of Kraichnan in the early 1950’s [

14], where it was already shown, by constructing an analogy with Hamiltonian dynamical systems, that there is an equipartition of the kinetic energy in the two incompressible velocity modes on the one hand and in the two acoustic (the longitudinal velocity and compressibility) modes on the other hand. A little bit less than forty years later, the first renormalisation group (RG) analysis was conducted on the compressible turbulence problem [

15], showing that, in the limit of zero viscosity, the renormalised Mach number converges towards a finite value, so that dissipation by shock waves as well as by momentum transfer between vortices coexist even in this limit. In the weakly compressible limit, it is found that the kinetic energy spectrum behaves as

being the incompressible K41 contribution—thus substantiating the claim that the K41 scaling holds beyond the very small Ma number values, a result consistent with most of the numerical studies presented above. In the case of a finite Mach number, it is found that the ratio of

to the compressible component

is a constant number, which means that, in the supersonic case, both contributions must share the same scaling with

k.

In a subsequent perturbative RG computation, Antonov and his group concluded that the first correction to the behavior of the kinetic energy spectrum with the Mach number should rather be , where is the mean energy dissipation rate, A is a numerical constant, and L is the macroscopic integral scale. This correction is much greater than that proposed by the group of Staroselsky.

Finally, in [

5], a re-examination of the concept of energy cascade in the context of compressible turbulent flows is proposed. It was found that the energy balance equation involves new terms, such as a crucial

-dependent term that gives rise to a new scaling regime in the supersonic regime with

, in close agreement with the numerical results of [

6]. These results have been complemented by further work deriving exact relations between correlation functions [

16,

17,

18,

19], although to the best of our knowledge, consequences in terms of the value of

have not been provided.

To our knowledge, there is no universally accepted scenario that could solve the above exposed controversies. If some discrepancies can be explained by the improvement of the computing techniques—both numerical and analytical—across the examined period, the true scaling laws controlling the statistics of compressible turbulent flows, if they exist, remain hidden by a veil of mystery. It is precisely the goal of the present work to provide a solid basis for the understanding of the scaling of the power spectrum of the energy (that is essentially the value of ) and therefore the way energy cascades are generated and maintained at the different scales.

More recently, L. Canet and her collaborators developed an RG technique that proved remarkably successful in the study of incompressible turbulence [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In particular, it was shown in [

20] that local and global symmetries of the Navier–Stokes action generated in the framework of Martin–Siggia–Rose–Janssen–de Dominicis (MSRJD) [

27,

28,

29] impose

exact relations between the correlation functions of the turbulence problems and their generating functionals. These exact relations put strong constraints on the possible forms of the evolution of these correlation functions with scale, and in turn, their scaling properties.

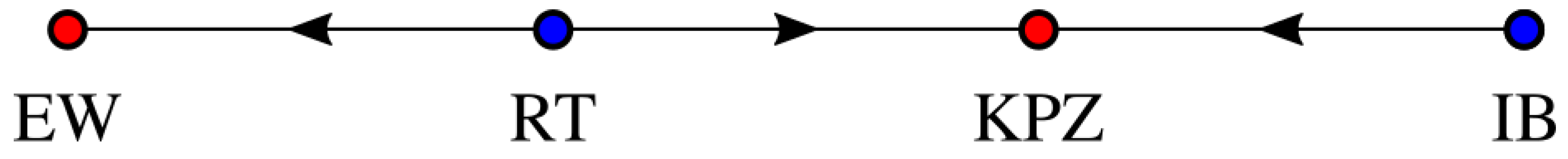

The aim of the present work is to adapt this formalism to the case of compressible flows and to investigate what predictions can be deduced from the symmetries of the compressible Navier–Stokes action. In particular, it is shown that the transverse and longitudinal sectors of the velocity field completely decouple, which leads to the usual K41 results in the limit of low Mach numbers as expected. But, more interestingly, this study also reveals that this does not impose that the longitudinal velocity mode behaves trivially. Indeed, contrary to previous studies, we show that its behavior is closer to the one of the 3D Burgers equation, which possesses two different possible infrared behaviors depending on the relative values of the viscosity and the dispersion of the forcing profile: one which scaling is fixed by the Edwards–Wilkinson model, consistent with a

scaling, and one corresponding to the Kardar–Parisi–Zhang (KPZ) universality class [

30], remarkably compatible with the solenoidal forcing prediction of [

6]. We also highlight, at the very fundamental level, how the symmetries of the action are broken as the Mach number augments and present the conclusions that can be drawn from this, although a complete derivation of the scaling relations in the large Mach number regime will be investigated in further work. Note that these breakthroughs are made possible by the fact that the formalism used here is fully non-perturbative and can thus be applied directly to a flow with any value of the Mach number, without needing further expansions.

The article is organised as follows: First, we derive the MSRJD field theory for the compressible Navier–Stokes fluid. Then, we derive from the symmetries of the action the different relations between the correlation functions. In the next section, the consequences of these relations on the scaling properties of the velocity correlation functions are explained. Finally, we conclude.

3. Symmetries and Ward Identities

In the context of an RG study in statistical field theory, two types of transformations of the microscopic action are of particular importance: (i) the transformations that leave the action invariant, (ii) the transformations for which the end result is linear in one of the microscopic field and can thus be re-absorbed in a redefinition of one of the sources in (

1). In both cases, the full generating functional is left unchanged, which yields exact relations, called Ward identities, relating the correlation functions and their generating functionals.

The study of the impact of such symmetries on the incompressible SNS action can be found in [

20]; as for the 3D viscous Burgers equation, it is given in [

30]. We will not reproduce the already derived relationships in this work, referring the interested reader to the two references above, but rather concentrate on the difference between the already known scenario and the compressible SNS case. In order to simplify our study, we can benefit from the decoupling property (

17) that allows us to study the transverse and longitudinal parts of the action separately.

3.1. The Transverse Action

We have shown above that the transverse part of the action has the form of the incompressible SNS action without the pressure term. This means for example that the pressure gauged symmetry

that ensured the preservation of the incompressibility property at all scales in the RG flow in the incompressible SNS case [

20] is not present anymore here. This is due to the definition of the transverse velocity field which is incompressible by definition.

We are not going to make a list of all the other symmetries that are not needed anymore, like the ones involving the pressure response field that does not appear, again, because incompressibility is enforced structurally here.

The major symmetry we have to study is the time-gauged Galilean symmetry,

being an arbitrary function of time.

This symmetry is crucial as in the incompressible case, it yields a Ward identity relating the different vertex functions exactly, which puts very strong constraints on the RG flow, and in particular driving it towards K41 in the inertial range. However, here, since has been promoted to a fluctuating field rather than a constant, the action of this transformation on the microscopic action is not linear in the fields anymore.

More precisely, in the limit of low Mach numbers,

, so that

is a constant to a good degree of approximation, and the usual Ward identity holds, leading among other things to the Kárman–Howarth relation [

20], and in turn, the K41 scaling. However, as the Mach number increases, this property is lost as the Ward identity is broken, leaving the scaling of the velocity correlation functions and thus that of the kinetic energy spectrum unconstrained. Whether this occurs abruptly in a two scaling fixed points kind of scenario or more progressively requires a specific RG model to study in detail the behavior of the RG flow, a task that we reserve for future work since we want to present here only general properties that stay valid no matter the truncation scheme devised for actual computations. A more precise statement about what happens in the case of moderate to high Mach numbers can still be sorted out, and it is presented a little bit further in our study.

All in all, in the limit of low Mach numbers (a precise definition of how low would, again, necessitate a precise RG model), the transverse part of the compressible SNS action behaves exactly as its incompressible counterpart. However, as the Mach number increases and the relative fluctuations of density becomes bigger, the symmetry that protected the K41 scaling in the inertial range vanishes, and the behavior of the velocity correlation functions is expected to change.

3.2. The Longitudinal Action

The longitudinal action is composed of two parts: (i) the matter conservation equation part and (ii) the 3D Burgers action with pressure part.

Before beginning our study, let us remark that the numerous auxiliary fields that are needed to enforce, in particular, the preservation of the longitudinal character of the velocity field in three dimensions, and which are meticulously described in [

30] are not present anymore, for the same reason as above, because this constraint is structurally there already.

We will thus first begin with the transformation that is absent from the usual Burgers equation, the pressure gauged shift:

Its effect on the action is linear in the longitudinal velocity response field, which leads to the following Ward identity:

Namely, the pressure sector is not renormalised. This situation is similar to that of the usual incompressible SNS case [

20] and should not be misinterpreted: given that there exists a non-trivial coupling to the diagonal, spin 0 part of the stress tensor at the level of the action; it cannot be excluded that an overpressure is generated within the renormalisation group process, and such a term would be added to the usual pressure term in the Burgers equation if one wants to compute the value of the pressure, under a given set of conditions, at a given point. But the crucial thing is that such a term would not in any case depend on the pressure that was present in the equation in the first place. This conclusion does not depend on the Mach number either since, when

is a fluctuating field, its place is in the kinetic term and not in front of the pressure term. Such a property seems to us to be particularly interesting as in almost all of the previously cited papers dealing with compressible turbulence, an equation of state, often of the form

,

being the speed of sound, was used in the derivation of the scaling laws, by numerical or analytical means. What we claim here is that, at least as long as RG analysis is concerned, such a hypothesis is not required at any point in the derivation. This simplifies a great deal the initial problem.

Second, let us examine the effect of a constant shift of the response density field:

The variation of the action is as follows:

where, in the last line, we used the fact that the two last terms of the first line are boundary terms. Hence, the nonlinear term cancels, and the resulting transformation is again linear in the fields, which allows us to write,

(where

).

The physical interpretation of this result is quite transparent: the mass conservation equation is enforced at all scales in the renormalisation group flow. But, the above equation also means that the mass conservation part of the effective action effectively decouples from the renormalisation group flow. Putting all these results together, we get that the renormalisation of the longitudinal part of the effective action is the same as that of the 3D Burgers model (since all the new terms decouple from the flow). This is a major simplification compared to the initial problem.

It should be understood though in the above comment that

is nonetheless still a fluctuating field. The fact that the mass conservation part is not coupled to the general flow means that the renormalisation of

is entirely determined as a function of that of

, not that the density field is not renormalised. The fact that the density field still fluctuates is of crucial importance, as we can already anticipate from the study of the transverse part of the action. It is also required for our results to be in agreement with the previous literature presented in the introduction: Indeed, if the longitudinal mode was the only acoustic mode, the study of Kraichnan [

14] would imply that the longitudinal velocity field alone carries the same amount of energy as the two transverse modes, which would also forbid scaling laws for the power spectrum that would be in agreement with the values found in previous studies.

Finally, a crucial symmetry is of course the time-gauged Galilean symmetry, but we are not going to reproduce the results here as they are exactly the same as in the incompressible case: In the limit of low Mach numbers, the symmetry behaves exactly as in the 3D Burgers model (see [

30]), and the scaling properties follow. As the Mach number increases, however, the relative fluctuation of

compared to its mean value is not negligible anymore, and the action of the time-gauged Galilean symmetry is not linear in the fluctuating fields anymore, which means that its action cannot be cancelled by a redefinition of the source terms. The importance of this symmetry should absolutely not be understated though, as it provides the scaling in the low Mach number limit. Indeed, as we are going to show, it enforces a scaling for the longitudinal mode that is different from that of the transverse modes, a result which supports a type of scenario like the one presented in [

6] with two types of modes with two types of scaling both contributing to the power spectrum of the kinetic energy dissipation.

3.3. Going Further with Bilinear Sources

Even restraining ourselves to exact statements true whatever the applied RG procedure, it is a bit frustrating not to have a Ward identity corresponding to the time-gauged Galilean symmetry in the case of moderate to high Mach numbers. As it turns out, this Ward identity provides a hierarchy of relationships between the successive vertex operators (the functional derivatives of with respect of the different fields involved) which is the backbone of the further RG analysis.

There is one way to go further than what we have done so far, which consists of adding to the definition of

two new source terms,

and

, that instead of coupling

linearly to the fields couple to a composite operator consisting of two fields evaluated at the same point. Explicitly, we add

and

. These two terms are not to be taken into account in the Legendre transform that defines

from

, so that the previous identities are not modified. However, it allows us to provide a form where the action of the time-gauged Galilean symmetry, augmented with the transformation of the density field

can be re-absorbed in a redefinition of the bilinear sources, finally leading to the following Ward identity:

It is important to note that the introduction of the bilinear source operators did not technically break the decoupling property, which can still be shown to exist in the new formalism, but it restored a coupling between the density mode and the transverse velocity fluctuations that was not present in the low Mach number limit. We insist again on the fact that it is not a fundamental breaking of the RG flow properties since we have shown that, even in the supersonic regime, the flow of the density field completely decouples, but the fact that the density field, which fluctuates in a way fixed by the renormalisation of the longitudinal component of the velocity, enters the fundamental equation at the basis of all the hierarchies between vertex operators even for the transverse modes shows how profound the consequences of going from the subsonic to the supersonic regime go.

It can be checked that (

26) yields back the usual Ward identities derived in [

20,

30] in the limit where

becomes a constant.

The lowest order equation of the above hierarchy is obtained when the average macroscopic fields are all taken to be 0, except

which becomes a constant, which yields the following identity:

The other equations are obtained by taking functional derivatives of (

26) with respect to the fields and evaluating it in the appropriate macroscopic field configuration.