1. Introduction

With advances in science and technology and growing production demands, the industrial sector is entering a new era—Industry 4.0 [

1]. As a traditional manufacturing sector, the textile industry is also experiencing a transformation towards automation and informatization. However, the contemporary textile industry is confronted with challenges such as overcapacity and intense competition, which necessitate the development of smart textile factories as a pivotal pathway for its transformation [

2]. The introduction of intelligent equipment such as mobile manipulators in processes like transportation and spinning in textile factories not only reduces labor costs and enhances productivity but also helps to ensure product quality, playing a significant role in the intelligent transformation of textile factories [

3].

In recent years, symmetry has assumed an increasingly important role in the modeling and control of robotic systems. Many redundant robots—particularly mobile manipulators—employ asymmetric mechanical architectures to enhance operational flexibility. Mobile manipulators combine the planar mobility of a mobile base with the precise operational capabilities of a multi-degree-of-freedom manipulator, greatly expanding the workspace and adapting to the complex and dynamic environments in textile factories. The study of inverse kinematics for manipulators involves, given a desired end-effector pose, calculating the joint angles of the manipulator. Such problems are often computationally intensive, have non-unique solutions, and require optimization of the results [

4]. However, incorporating a mobile base introduces nonholonomic constraints and additional redundant degrees of freedom. This substantially increases model complexity and makes the inverse kinematics problem more challenging [

5]. Thus, how to accurately and efficiently solve the inverse kinematics of mobile manipulators has become an important research topic in the field of robotics.

R. Raja et al. proposed an improved KSOM learning framework to learn the mapping between the joint angle space and Cartesian space, addressing the inverse kinematics problem of mobile manipulators and maximizing the operability of the manipulator during the solution process [

6]. Khan et al. transformed the tracking problem of mobile manipulators into a constrained position-level optimization problem and employed an improved recurrent neural network algorithm to solve the inverse kinematics under nonholonomic constraints, verifying the stability and convergence of the algorithm [

7]. Zhao et al., by integrating task space constraints, joint limit constraints, and collision-free constraints with obstacles, proposed a novel algorithm based on Newton’s method and first-order techniques to generate collision-free inverse kinematics solutions, achieving dynamic obstacle avoidance for spherical obstacles [

8]. Abbireddy et al. formulated the IK problem of a redundant manipulator as a nonlinear constrained optimization problem, whose objective is to minimize the position and orientation errors while avoiding obstacles. The classical nonlinear optimization method SQP, together with obstacle-avoidance techniques, was employed to determine the joint variables, and a bounding-box-based method was used to achieve collision avoidance [

9]. Zhang et al. introduced a fast solving framework for mobile manipulators with unique domain constraints, along with a real-time obstacle avoidance strategy for the manipulator [

10]. Li et al. introduced six parameters to characterize the motion redundancy and transformed the inverse kinematics of dual mobile manipulators into a non-redundant inverse kinematics problem. Subsequently, a weighted product form of normalized ideal redundant behaviors was constructed as the objective function. Finally, the Nelder–Mead simplex method was employed to optimize the redundancy parameters, thereby obtaining the desired joint configuration [

11]. Jin et al. treated the mobile base and the manipulator as an integrated system and designed a fully connected network (FCN) to predict the positions and joint configurations of all degrees of freedom based on the target pose, achieving an online optimization for the whole-body inverse kinematics of the mobile manipulator. However, compared to the commonly used NNO algorithm, this method requires a longer computation time and its optimization speed needs improvement [

12]. Xu et al. simplifies the inverse kinematics problem of the nine-axis gantry robot into that of a six-axis robotic arm. Through simulation experiments and specific experiments on the Staubli RX160L robotic arm, the accuracy of the inverse kinematics analysis of the robot was confirmed [

13]. However, the aforementioned algorithms often rely on complex computations or extensive data training, thereby increasing the cost of solving the inverse kinematics. In response to these shortcomings, an increasing number of researchers have begun to employ intelligent optimization algorithms that do not rely on data training and have lower computational complexity to solve the inverse kinematics problem of mobile manipulators. Algorithms such as Differential Evolution [

14], Fruit Fly Optimization [

15], Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm [

16], Particle Swarm Optimization [

17] and Bald Eagle Search Optimization Algorithm [

18] have all been validated for their effectiveness in solving these problems.

Among the intelligent optimization algorithms previously referenced, Particle Swarm Optimization is distinguished by its simple structure and ease of implementation, and is frequently employed to solve complex constrained problems. It has been extensively applied to the inverse kinematics problem of mobile manipulators. Ram et al., targeting mobile manipulators in complex environments, formulated a multi-objective optimization problem with objectives of minimizing pose error and total joint movement, and with obstacle avoidance as a constraint, thereby achieving joint decoupling and an inverse kinematics solution for the mobile manipulator [

19]. For SSRMS-type redundant manipulators, Jin et al. introduced the elbow joint posture and derived the algebraic relationship between the elbow posture and joint angles. By incorporating obstacle avoidance and singularity avoidance as additional tasks to constrain the particle swarm algorithm, the approach demonstrated satisfactory performance in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and operability, although it did not account for joint limit issues [

20]. Liu et al., for general manipulators that do not satisfy the Pieper criterion, employed an improved particle swarm algorithm to solve their inverse kinematics. They introduced a nonlinear dynamic inertia weight adjustment method based on the concept of similarity and simultaneously utilized multiple populations for the search, thereby enhancing the stability of the inverse solution [

21]. Cao et al. presents an improved quantum particle swarm optimization algorithm (IQPSO), which is used to solve the inverse kinematics problems. In this algorithm, quantum behavior is added to the particle swarm optimization algorithm, improve the convergence speed and solution accuracy [

22]. Ning et al. proposed an adaptive transfer particle swarm algorithm (VDMAT-PSO) based on measures of velocity and directional manipulability, providing a solution for the inverse kinematics of mobile manipulators [

23]. These approaches demonstrate the effectiveness of PSO-based solvers, but each focuses on specific aspects of performance. Challenges such as ensuring a well-distributed search in the high-dimensional solution space and avoiding premature convergence remain unsolved in many cases. In particular, no prior work has integrated multiple advanced PSO strategies into a unified solver for the IK problem of mobile manipulators. This gap means that existing methods may still suffer from uneven exploration of the redundant solution space or early stagnation in local optima.

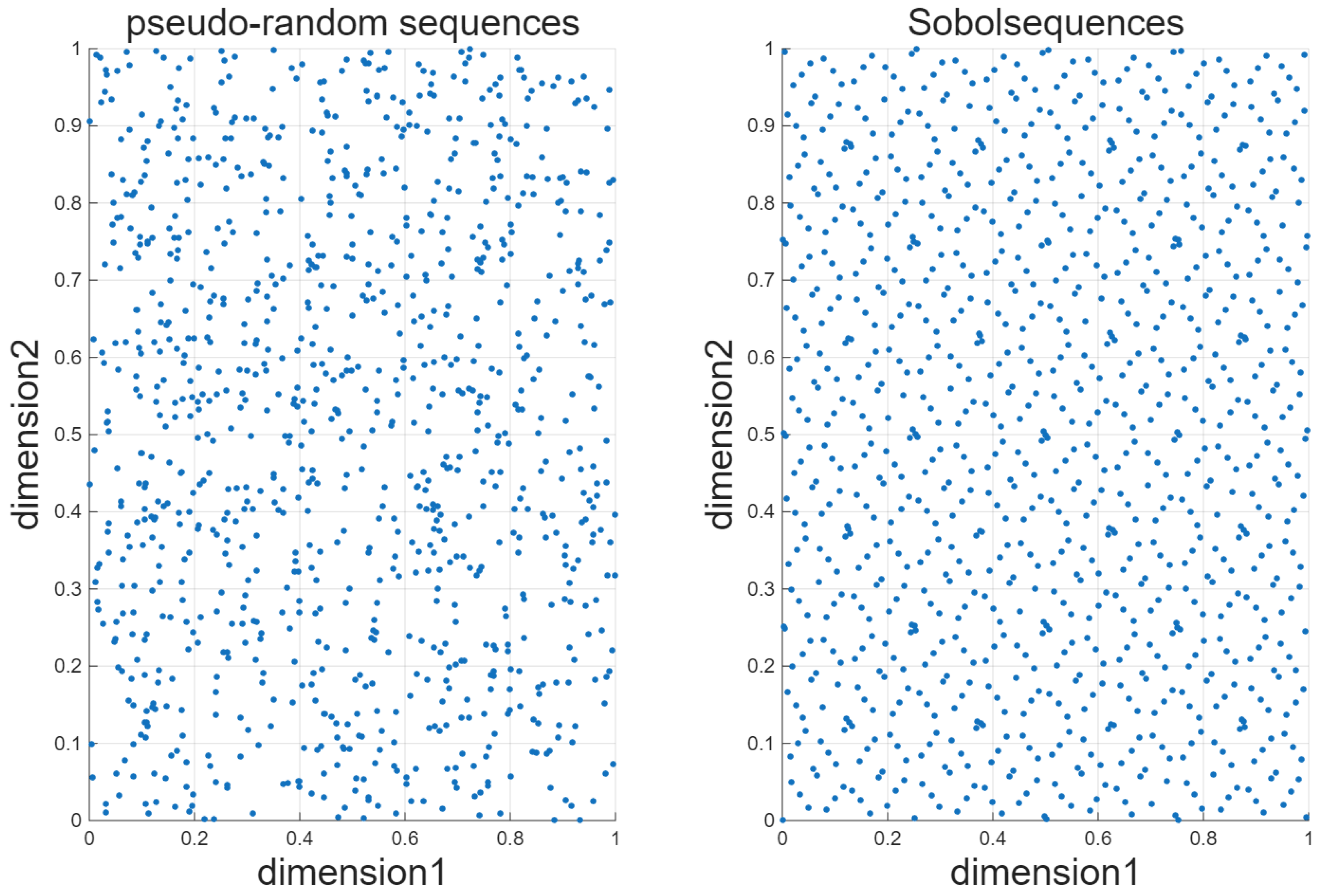

In recent years, researchers have increasingly leveraged system symmetry in kinematic modeling, controller architectures, and optimization algorithms to simplify computation and improve performance. Correspondingly, deliberately introduced asymmetries—such as nonuniform gains or perturbations in control strategies—have become a growing trend for enhancing robustness and adaptability. By jointly exploiting symmetry and asymmetry in algorithmic and control design, robotic systems achieve improved stability and performance in complex, uncertain environments. To address the limitations of PSO solvers mentioned above, we propose a targeted integrated optimization strategy for IK, which combines several techniques in a novel way. We refer to this improved algorithm as Chaotic Mutation PSO (CMPSO). The integration of these three strategies is specifically designed to balance solution-set distribution and convergence quality in the redundant, high-dimensional search space of a mobile manipulator. We highlight the synergy of the integrated strategies: Sobol initialization ensures a high-quality, uniformly distributed starting population. The logistic chaotic perturbation introduces asymmetry in the swarm’s evolution, preventing synchronized premature convergence by re-diversifying particles when they approach boundaries. The Gaussian–Cauchy mutation adaptively balances local fine-tuning and global exploration, helping particles escape local optima while maintaining convergence precision. Together, these mechanisms complement each other to significantly improve the algorithm’s global search ability, population diversity, and solution accuracy. We apply the proposed CMPSO to a 9-DOF mobile manipulator’s IK problem and conduct extensive simulations, including single-point IK solving and continuous trajectory planning. Comparative experiments against the standard PSO and other enhanced variants demonstrate that our integrated approach achieves superior accuracy, stability, and efficiency.

3. Simulation and Results

All experiments in this study were conducted on a computer running Windows 11 and equipped with a 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-13620H processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 2.40 GHz. Python 3.13.0 was used as the simulation environment. Inverse kinematics tests were performed for both single-point and continuous-point cases.

3.1. Single-Point Inverse Kinematics Ablation Experiment

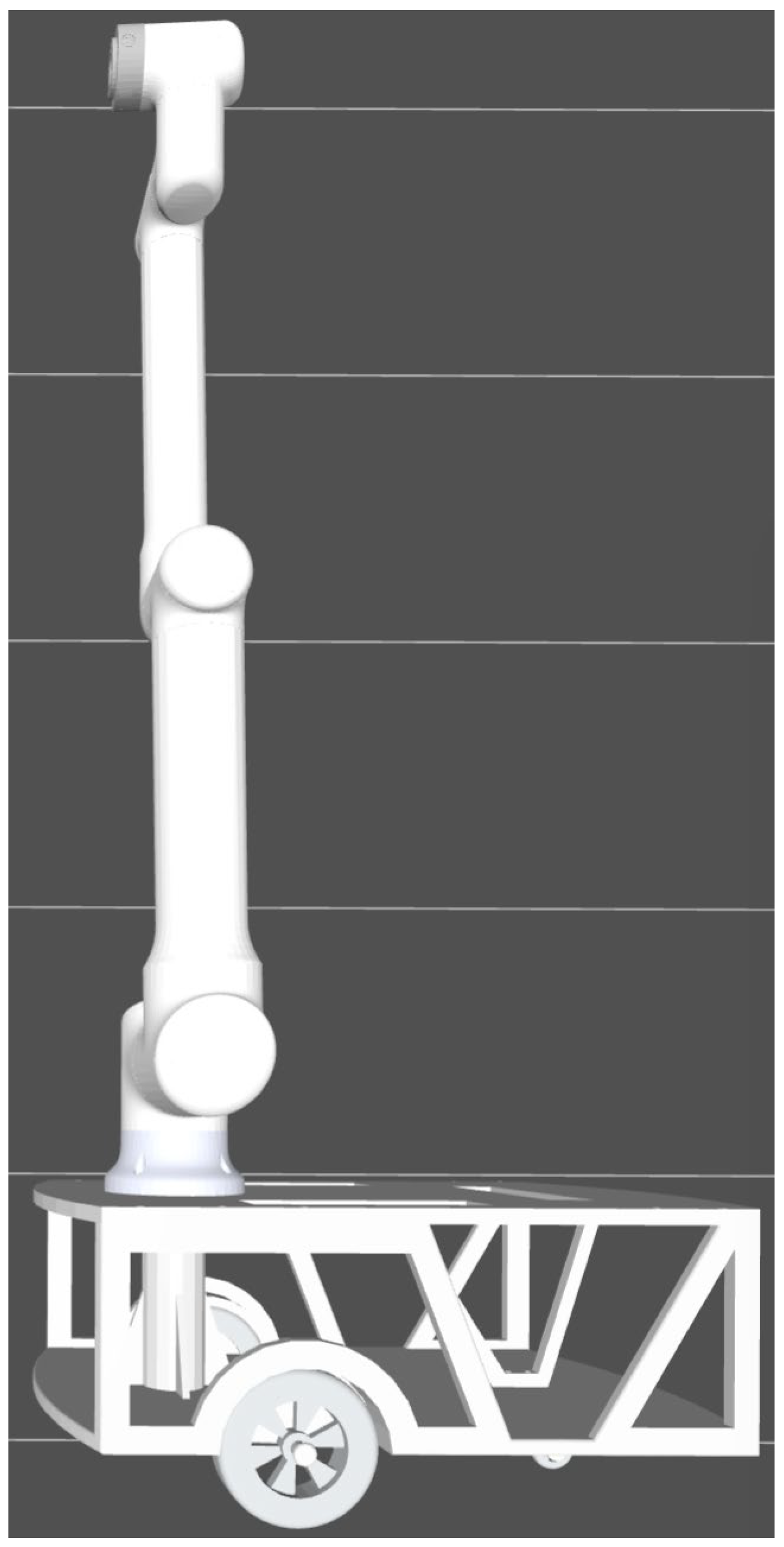

To thoroughly verify the effectiveness of the CMPSO improvement strategies, ablation experiments are first conducted. For the mobile manipulator in the textile workshop shown in

Figure 1, ablation tests of inverse kinematics based on the chaotic-mutated particle swarm optimization algorithm are performed following the algorithm flow described in

Section 2.2.3. The specific procedure is as follows: given the desired end-effector pose and the initial pose of the mobile manipulator, the improvement strategies of CMPSO are removed individually, and the nine joint variables of the mobile manipulator are solved accordingly. The obtained joint solutions are then substituted into the forward kinematics to compute the actual end-effector pose, and the error relative to the desired pose is evaluated. The algorithm parameters are set as follows: the maximum number of iterations is

T = 500, and the population size is

N = 30; the extrema of the inertia weight are

and

; acceleration coefficients

; to ensure that the particles remain in a fully chaotic state, the chaotic coefficient is chosen as

r = 4. The initial configuration of the mobile manipulator is set as:

The desired homogeneous transformation matrix corresponding to the end-effector is given by:

The position error for the single-point inverse kinematics solution is defined as:

and the orientation error is defined as:

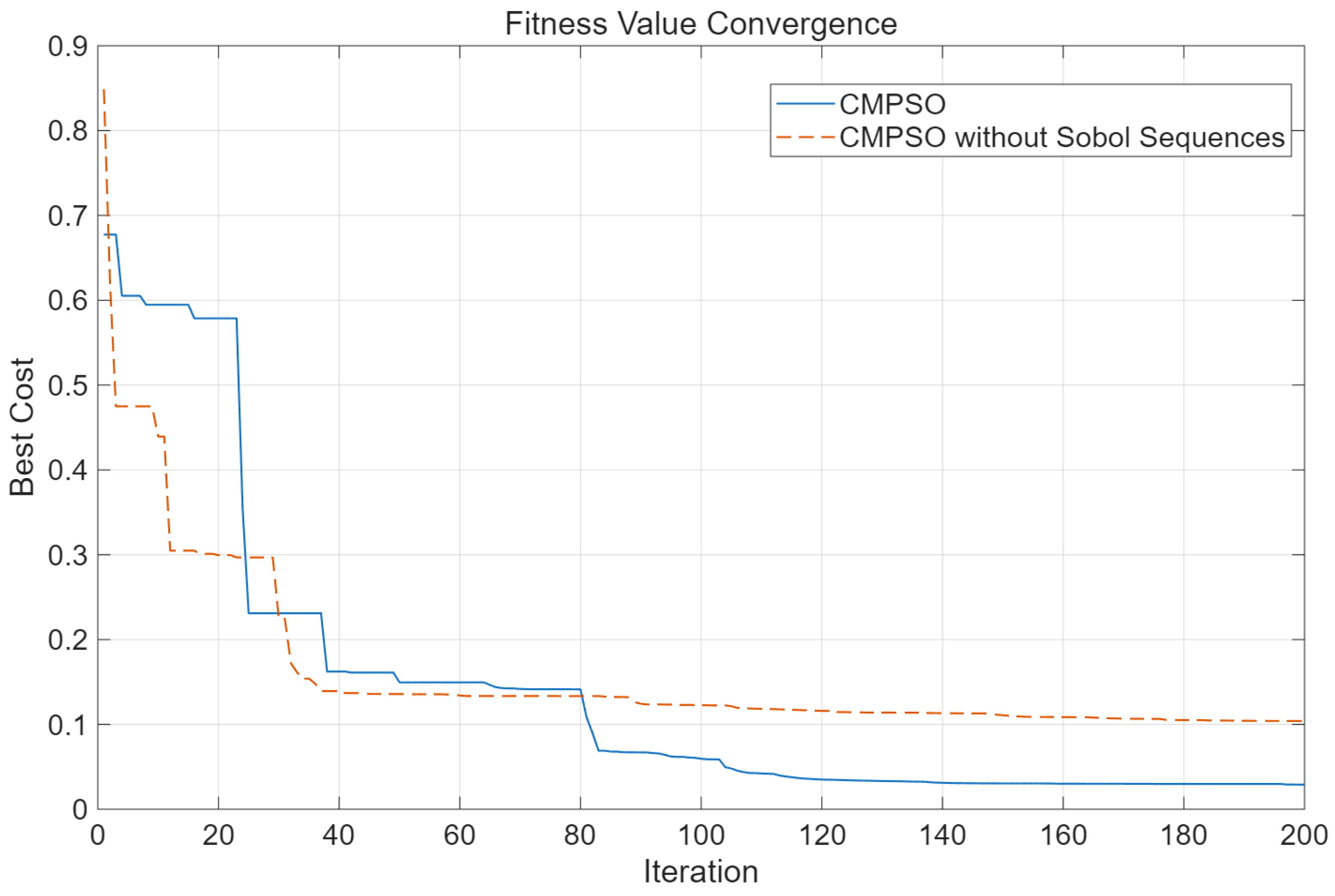

In this experiment, the Sobol sequence-based population initialization method in CMPSO was removed. The convergence curves of the fitness values are shown in

Figure 5.

It can be observed that the original CMPSO (before removal) exhibits a lower initial fitness value. This is because the Sobol sequence-based initialization distributes particles more uniformly within the feasible domain, resulting in a higher-quality global optimum in the initial state. Moreover, due to this uniformly distributed starting condition, the algorithm is able to converge toward a better solution in the later stages.

- 2.

Ablation Experiment on Particle Boundary-Handling Strategy

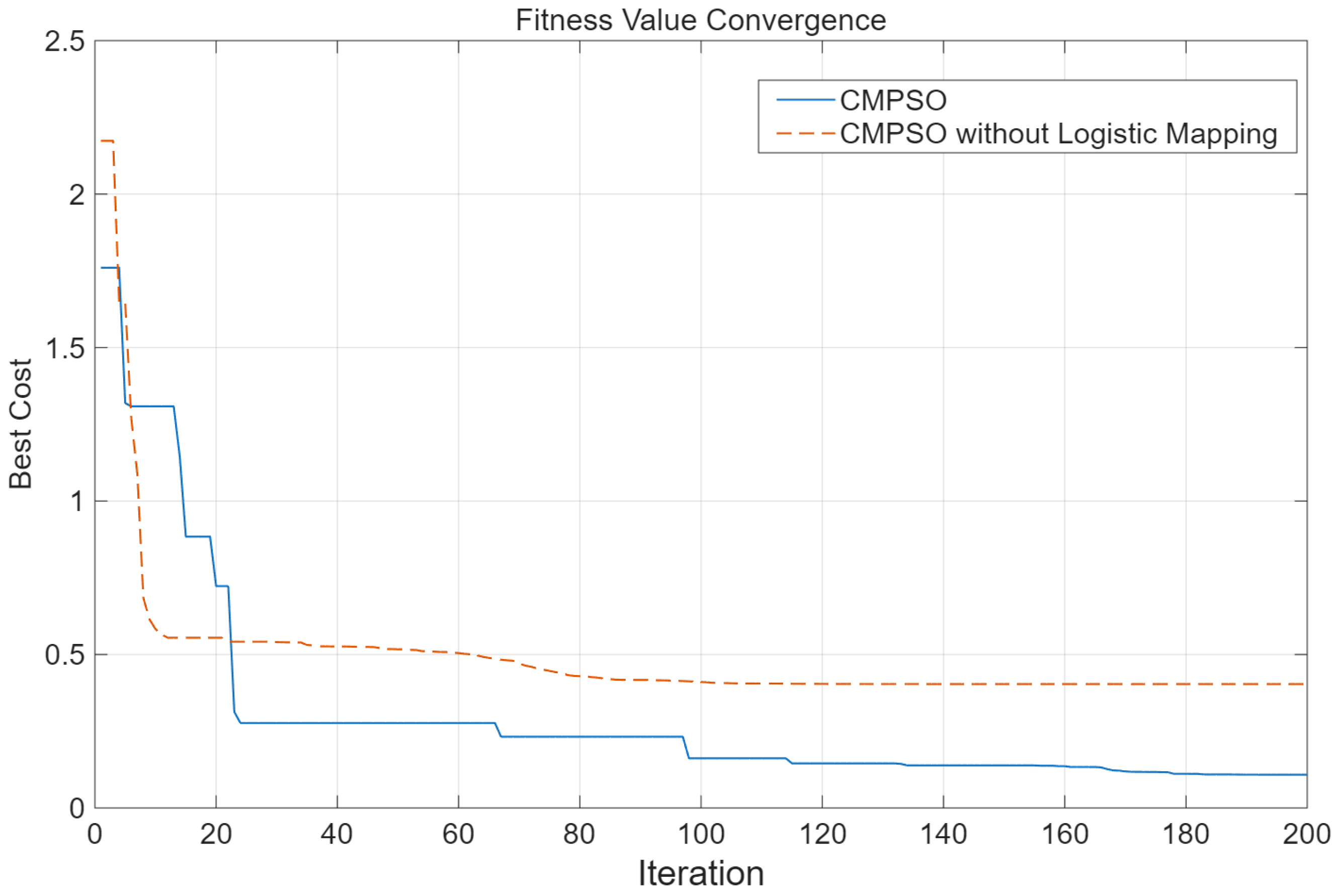

In this experiment, the Logistic mapping-based boundary-handling method in CMPSO was removed. The convergence curves of the fitness values are shown in

Figure 6.

It can be observed that when a simple truncation method is used for boundary handling, the algorithm falls into a local optimum during the early and middle stages of iteration and fails to escape. In contrast, the CMPSO algorithm maintains a consistent convergence trend throughout the iterative process. This is because the Logistic mapping-based boundary-handling strategy allows particles that move outside the feasible domain to return uniformly to the feasible region rather than being fixed at the boundary, thereby enhancing their ability to re-explore the search space.

- 3.

Ablation Experiment on Particle Mutation Strategy

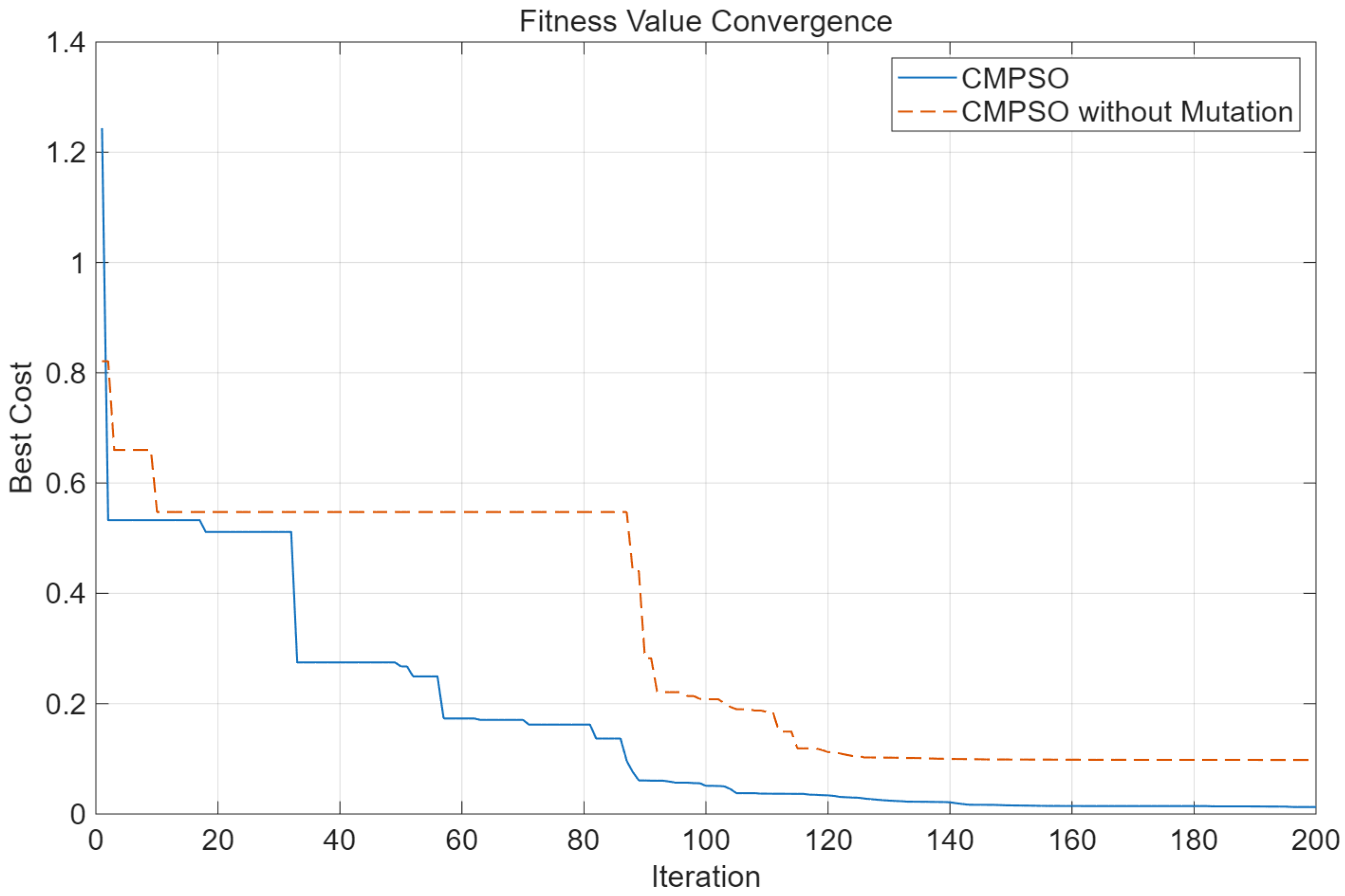

In this experiment, the adaptive mutation strategy of particles was removed. The convergence curves of the fitness values are shown in

Figure 7.

It can be observed that CMPSO exhibits more pronounced and frequent stepwise convergence behavior and ultimately finds a better feasible solution. This is because, with the adaptive mutation strategy, particles selectively undergo Gaussian mutation or Cauchy mutation based on their current fitness values, which greatly enhances their ability to escape local optima. As a result, the fitness curve demonstrates stepwise changes. This mutation mechanism significantly improves the search capability of particles, enabling CMPSO to achieve higher solution accuracy in inverse kinematics computation.

3.2. Single-Point Inverse Kinematics Comparison Experiment

The proposed CMPSO is compared with the standard PSO, Adaptive PSO (APSO) [

17], and Quantum-behaved PSO (QPSO) [

28] in inverse kinematics experiments. The basic algorithm parameters are the same as those in

Section 3.1, and the remaining algorithm parameters are set as follows: acceleration coefficient range for APSO as

, and contraction–expansion factors for QPSO as

,

. The convergence curves depicting the variation in the fitness value with iteration are shown in

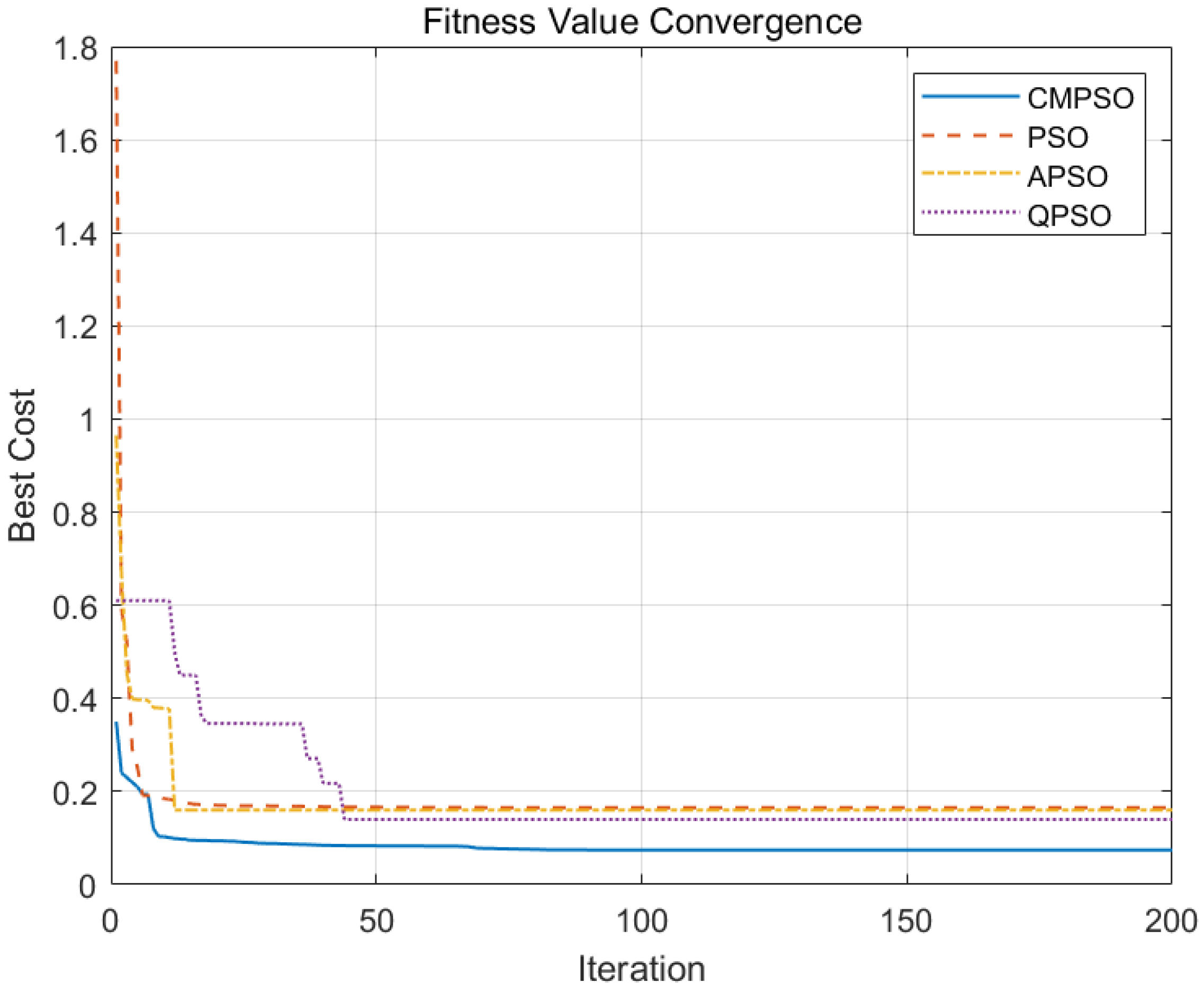

Figure 8.

Analysis of the convergence curves shows that compared with the other three algorithms, CMPSO starts with a lower initial fitness value due to the use of the Sobol sequence for population initialization, which results in a more uniform distribution of particles in the search space. As the iterations proceed, CMPSO converges the fastest and achieves the highest solution accuracy.

Fifty independent runs were conducted for each algorithm, recording the best fitness value, worst fitness value, mean fitness value, fitness variance, and the average pose error. The pose error is defined as

. The stability of the algorithms was analyzed, and the results are summarized in

Table 2.

From

Table 2, it can be seen that compared with PSO, APSO, and QPSO, the proposed CMPSO exhibits the smallest mean fitness value and variance, indicating superior stability and convergence, with the average pose error reduced by 70.15%, 54.39%, and 36.05%, respectively. This significantly enhances the accuracy of the inverse kinematics solution.

Inverse kinematics serves as the foundation for subsequent trajectory planning. The time performance of the algorithm determines whether the mobile manipulator can achieve real-time trajectory planning; therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the computational efficiency of the algorithm and further optimize its time complexity when required. According to our previous research, the mobile manipulator studied in this work must operate at a control frequency of at least 250 Hz in the textile workshop. Thus, the solution time of the inverse kinematics algorithm should be less than 4 ms. A total of 1000 inverse kinematics computations were randomly performed within the workspace of the mobile manipulator, and the computation times of the proposed CMPSO as well as PSO, APSO, and QPSO are summarized in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, the proposed CMPSO-based inverse kinematics algorithm exhibits significantly superior time performance compared with the other three PSO variants in the random experiments. This improvement is attributed to the designed joint-limit-avoidance constraint, which keeps the manipulator joints away from singular configurations, enhances manipulability, and reduces the computational cost of matrix operations. Based on the maximum and average computation times of CMPSO, the proposed inverse kinematics algorithm can almost satisfy a 1 kHz control frequency, which is much higher than the required 250 Hz. Furthermore, the low variance indicates that the computation efficiency of CMPSO is highly stable, fulfilling the requirements of real-time trajectory planning.

We define successful computation as the case in which the solution error converges to within 1% of the desired pose, upon which the algorithm terminates; otherwise, the computation is considered a failure. Similarly, 1000 random solution experiments were conducted within the workspace of the mobile manipulator, and the computation times for successful solutions are summarized in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, when convergence error rather than iteration count is used as the termination criterion (a criterion that is evidently more consistent with real robot operation and commonly adopted in robotic control), the computational efficiency advantage of the proposed CMPSO-based inverse kinematics algorithm becomes even more significant, consistent with the results shown in

Figure 8. Due to the more uniform population initialization, the algorithm uniformly covers the feasible domain in the initial phase, reducing the difficulty of convergence. Additionally, the adaptive mutation strategy greatly improves the success rate of the algorithm.

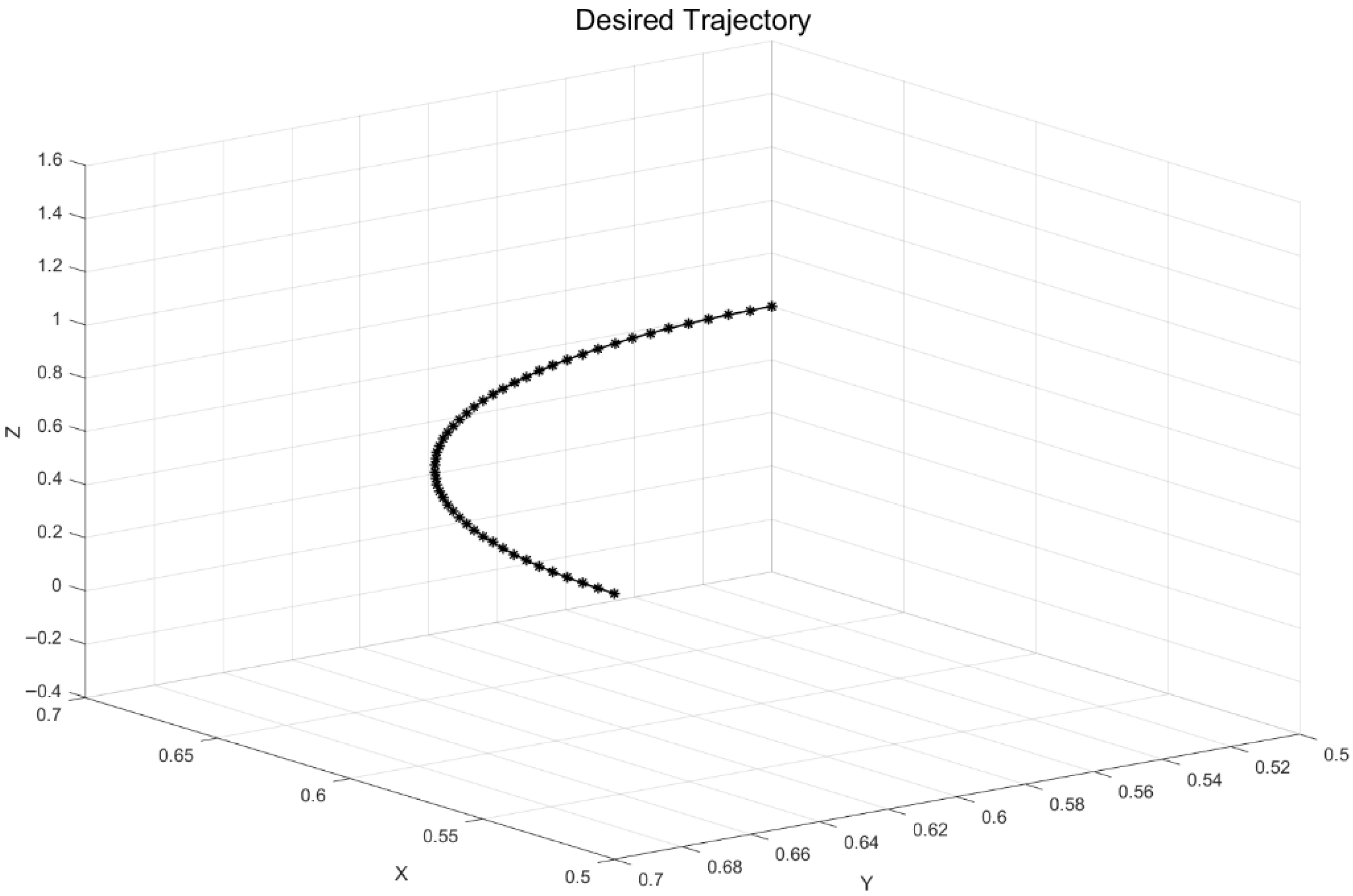

3.3. Trajectory Planning Experiment

Section 3.1 has verified the feasibility of the algorithm in solving single-point inverse kinematics. On this basis, a trajectory planning test for the mobile manipulator is conducted to further validate the algorithm’s performance in motion control. The specific method is as follows: two points in the manipulator’s workspace

and

, representing a pick-up point and a placement point in the textile workshop, are given. A circular arc in space with a center at

and a radius of 0.2 is planned between these two points. A fifth-order polynomial is used for trajectory planning along the circular arc, and 50 interpolation points are obtained based on the interpolation period, as shown in

Figure 9.

In this study, the circular end-effector path is discretized into 50 interpolation points. This number of waypoints provides a sufficiently fine spatial resolution for the given radius and workspace scale, so that the discrete points closely approximate a smooth continuous trajectory while keeping the experimental setup and figures concise. It should be noted that the proposed CMPSO-based inverse kinematics solver treats each interpolation point as an independent optimization problem. Therefore, the algorithm can be directly applied to trajectories with a larger number of interpolation points or to longer and more complex paths without any modification of the optimization framework. Combined with the timing results reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4, where the average computation time per IK query remains well below the 4 ms budget required by a 250 Hz control frequency, this indicates that the proposed method is suitable for real-time trajectory generation even for significantly denser discretizations.

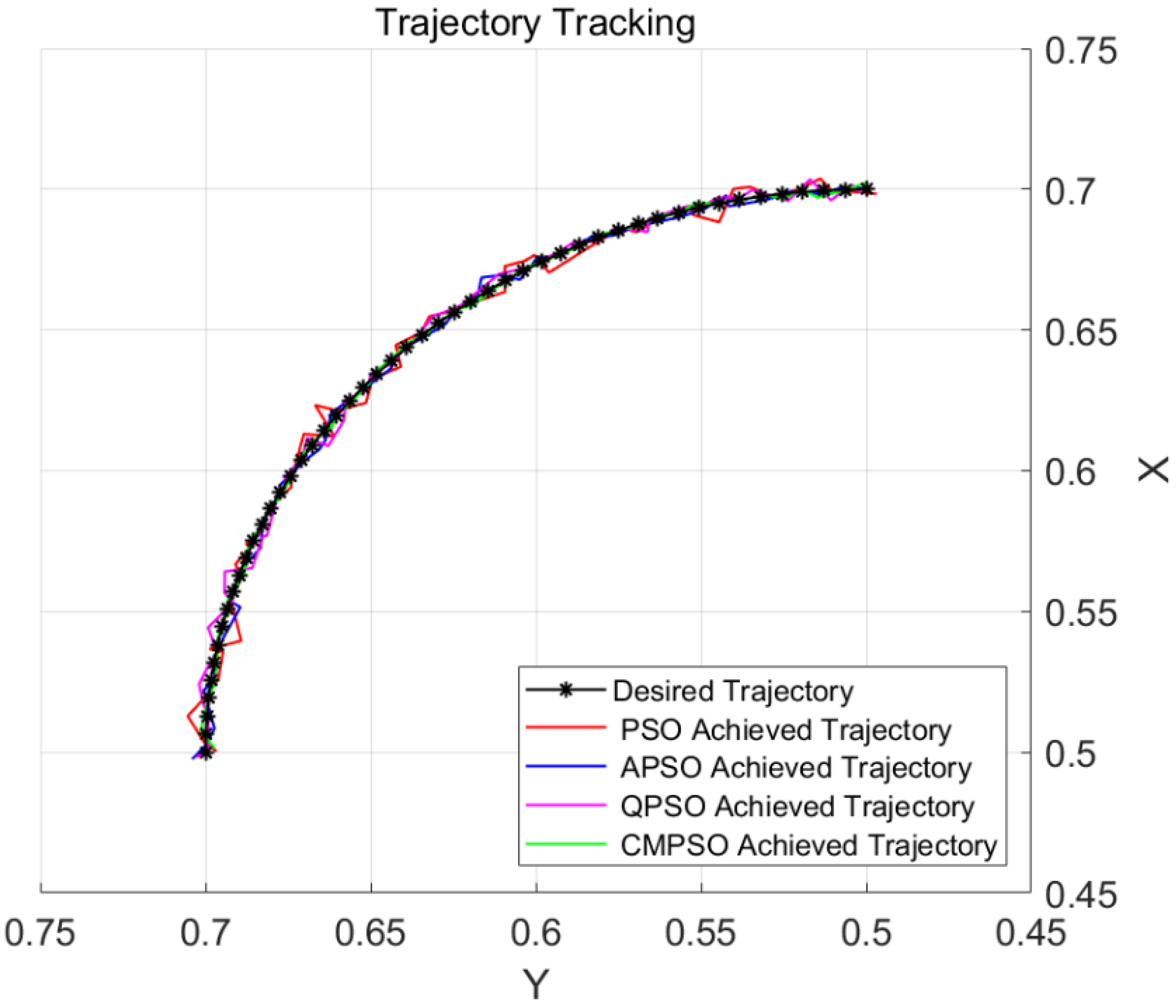

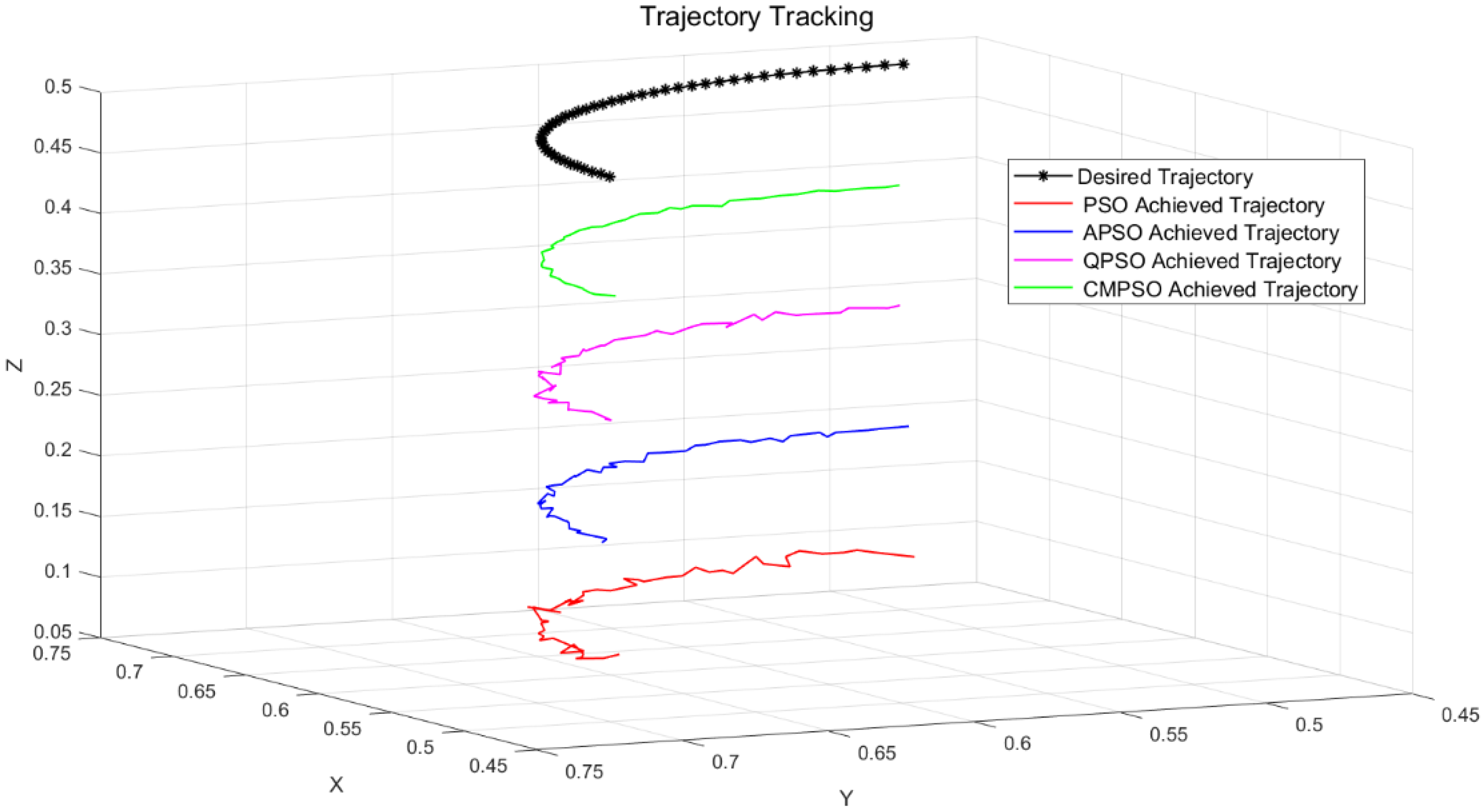

During the trajectory planning process, the PSO algorithm uses the previously computed trajectory point as the starting pose for the current iteration. The first starting pose is the same as that in Equation (21). The pose solutions computed by the algorithm are substituted into Equation (5) to extract and plot the position vectors

. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional comparisons are presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 (in the three-dimensional view, the trajectory has been translated in the z-direction for visual clarity).

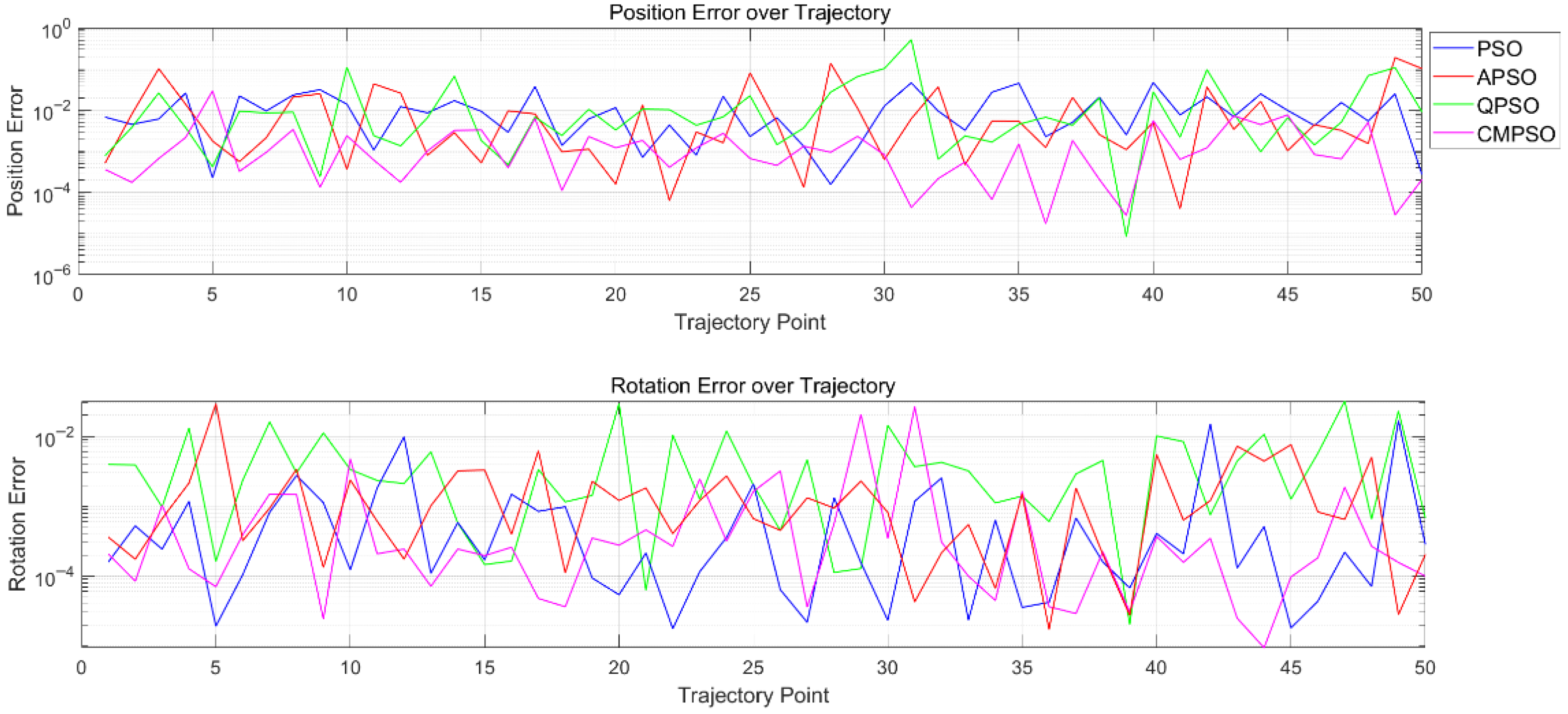

For the 50 trajectory points obtained, the position and orientation errors are calculated based on the definitions in Equations (23) and (24), respectively. The results are illustrated in

Figure 12.

Analysis of

Figure 8 reveals that the pose error curve obtained by the proposed CMPSO is lower in value and smoother compared to the other three algorithms. The error remains within a limited range

, indicating a high degree of solution accuracy. These experimental results are consistent with those presented in

Section 3.1 and demonstrate that CMPSO has superior precision and stability in solving the inverse kinematics problem.

4. Discussion

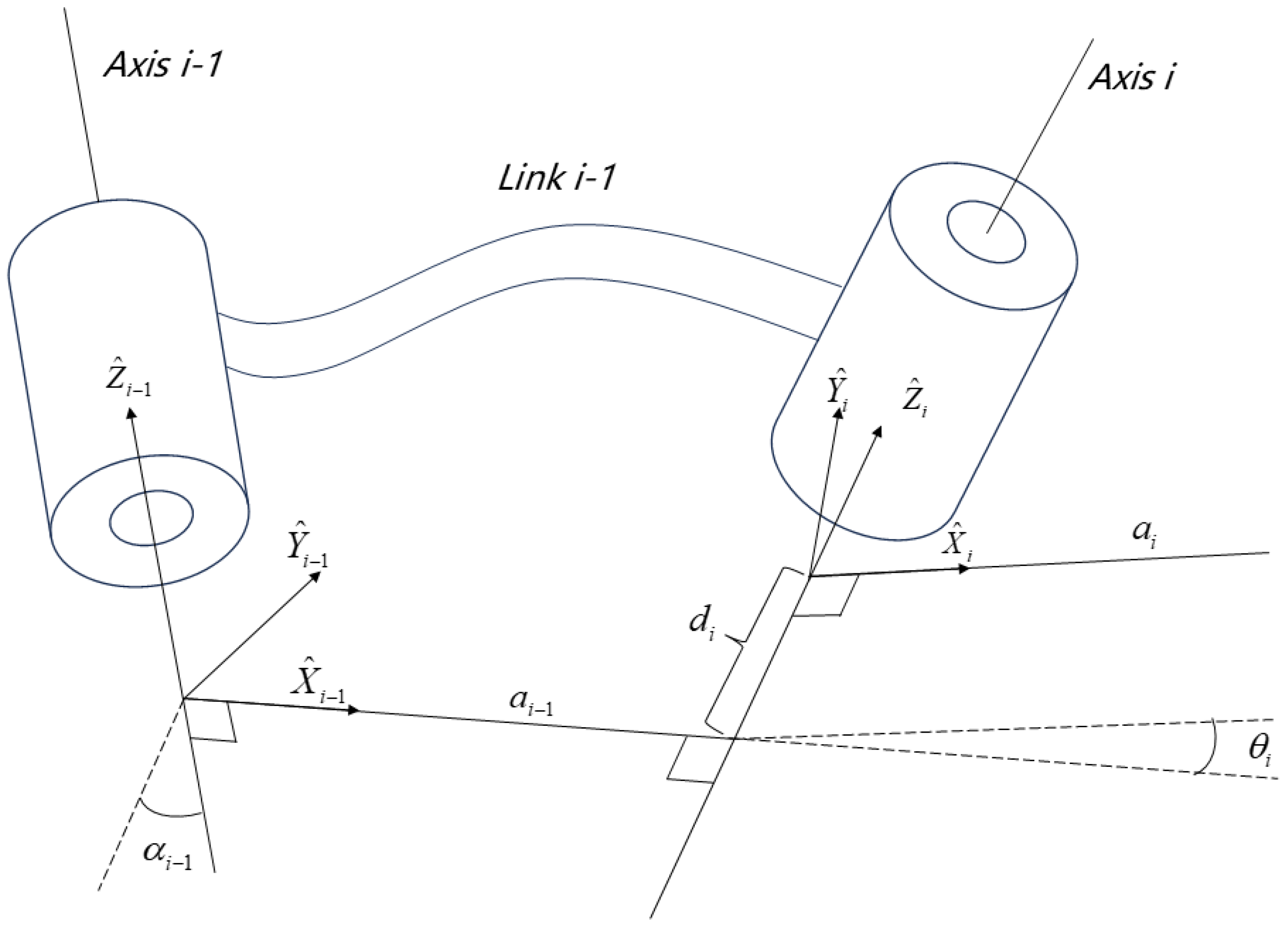

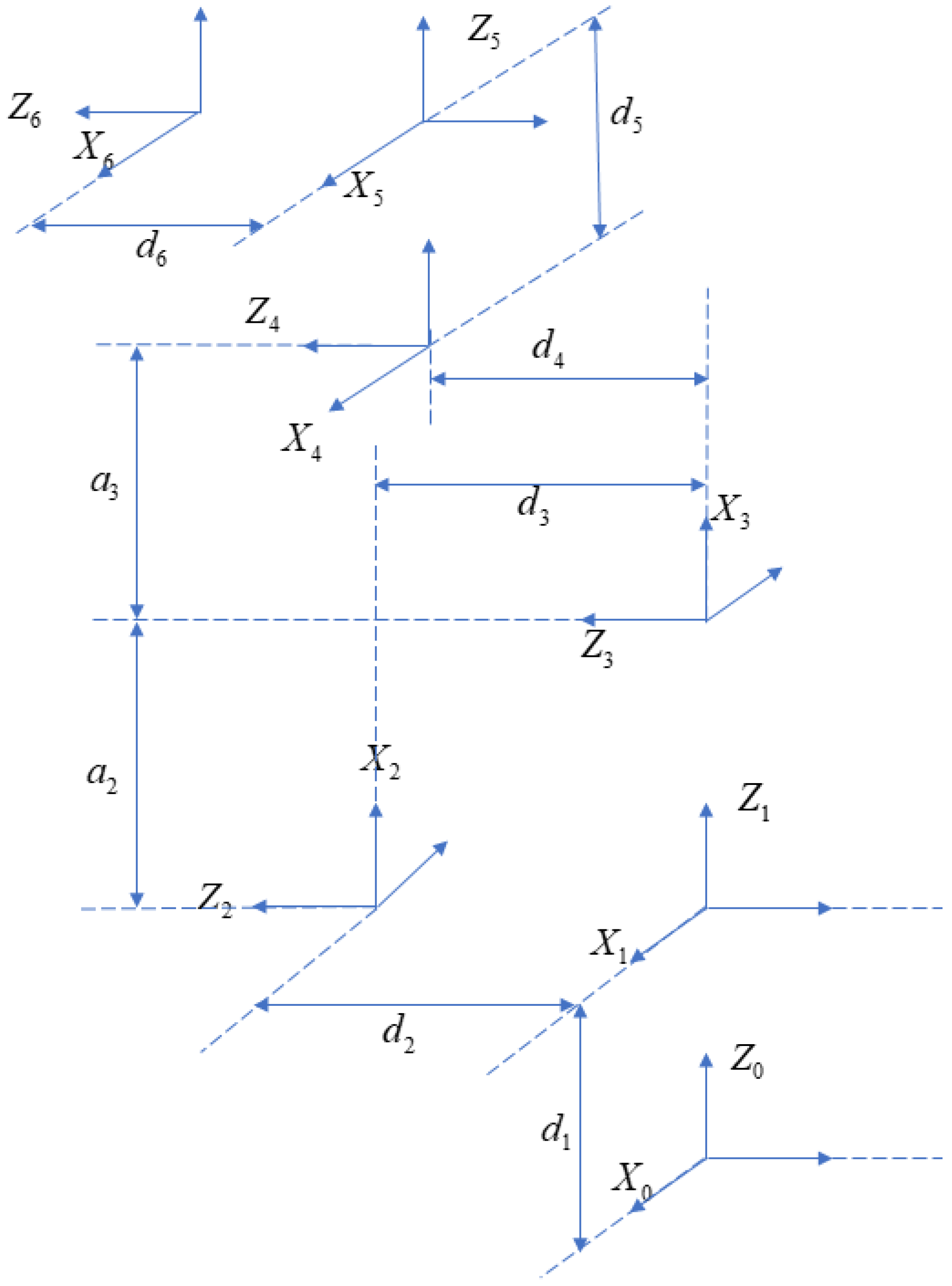

In this paper, we addressed the inverse kinematics problem of a mobile manipulator operating in a textile workshop and proposed a CMPSO-based solution capable of achieving high accuracy. By analyzing the coordinate transformation relationships of the mobile manipulator system and adopting the D–H convention, we first established the forward kinematic model of the 9-DOF mobile manipulator. Based on pose error, a “compliance” principle, and joint-limit avoidance, a multi-objective inverse kinematics model was formulated. To overcome the shortcomings of the standard PSO, such as uneven initial population distribution, premature convergence, and a tendency to be trapped in local optima, we introduced three enhancements: Sobol-sequence-based population initialization, logistic-map-based chaotic handling of boundary violations, and a weighted adaptive Gaussian–Cauchy mutation for inferior particles. These components were integrated into a chaotic mutation PSO (CMPSO) algorithm and applied to the multi-objective IK model.

Extensive simulations, including single-point IK solving and trajectory-planning experiments, demonstrated that the proposed CMPSO achieves higher precision and stability compared with the standard PSO and two other enhanced PSO variants (APSO and QPSO). CMPSO consistently yielded the smallest average pose error and variance, indicating superior solution quality and robustness. Moreover, the timing analysis showed that the average computation time per IK query is well below 1 ms, and even the worst-case runtimes satisfy the 4 ms budget required by a 250 Hz control frequency. This implies that the proposed solver is not only suitable for off-line planning, but also has strong potential for real-time control applications, such as online trajectory tracking and whole-body motion generation of mobile manipulators in textile production lines.

Beyond the textile manipulator studied here, the proposed CMPSO framework is largely independent of specific kinematic structures. It requires only the forward kinematics and task-space error definition. As such, it can be extended to other redundant robot systems, including different types of wheeled mobile manipulators and fixed-base manipulators that do not satisfy the Pieper criterion. For these systems, the integrated Sobol initialization, chaotic boundary handling, and adaptive Gaussian–Cauchy mutation are expected to provide similar benefits in terms of maintaining solution-set diversity and improving convergence accuracy in high-dimensional redundant spaces.

From a deployment perspective, several practical considerations will be important for industrial adoption. These include implementing the CMPSO-based IK solver on embedded or industrial controllers with limited computational resources, coping with model uncertainties and sensor noise, and enforcing strict joint, velocity, and workspace constraints to ensure safe operation in cluttered textile factory environments. While the current work focuses on detailed simulations, future research will investigate real-robot validation on a mobile manipulator platform in a textile workshop, integrating the proposed solver with low-level motion controllers and perception modules. This will allow us to evaluate the algorithm under real-world disturbances and hardware limitations and to further refine the method for long-term, reliable deployment in industrial scenarios.