Symmetry-Guided Theoretical Study on Photoexcitation Characteristics of CdSe Quantum Dots Hybridized with Graphene and BN

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Construction and Calculation Method

3. Results and Discussion

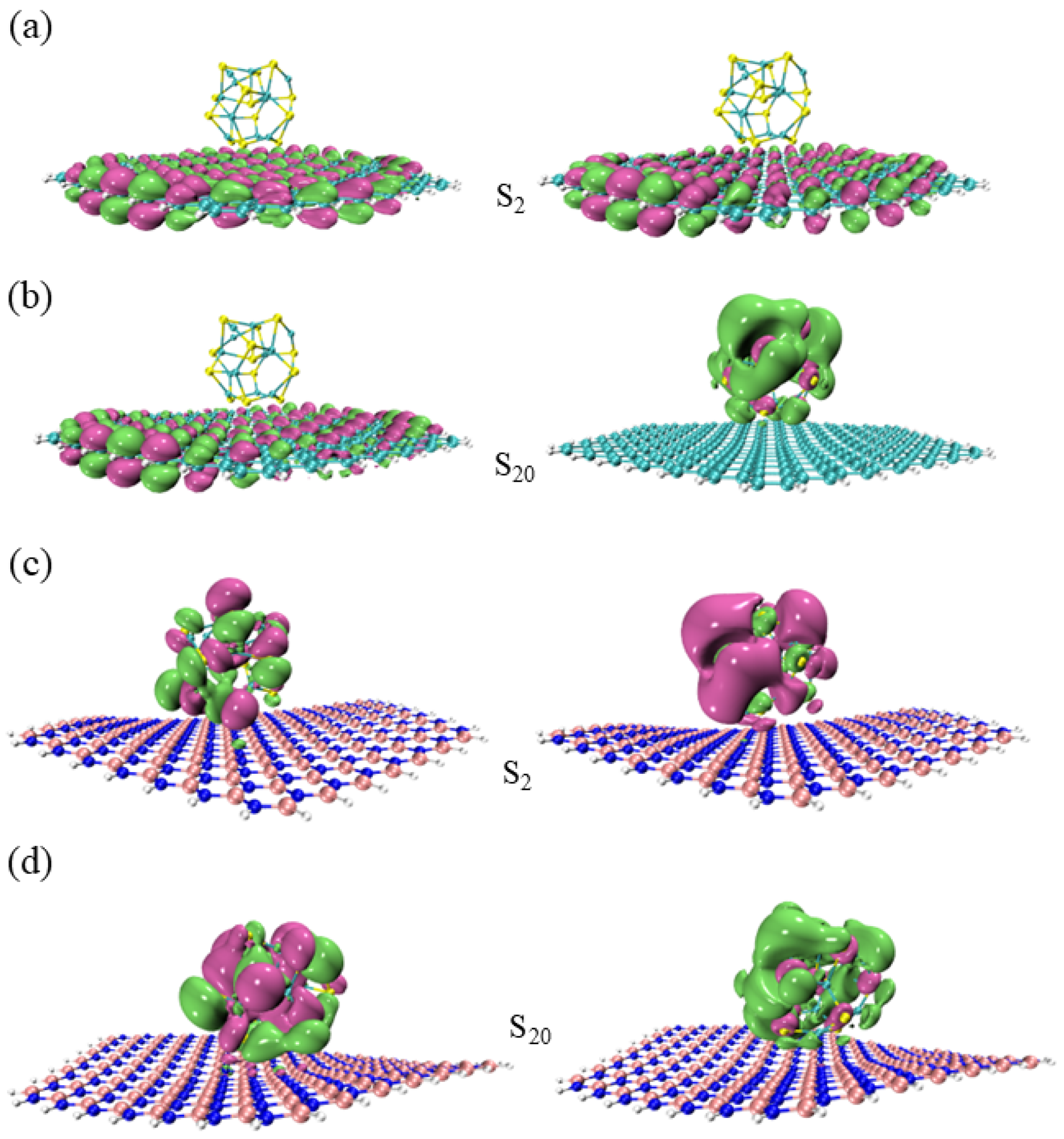

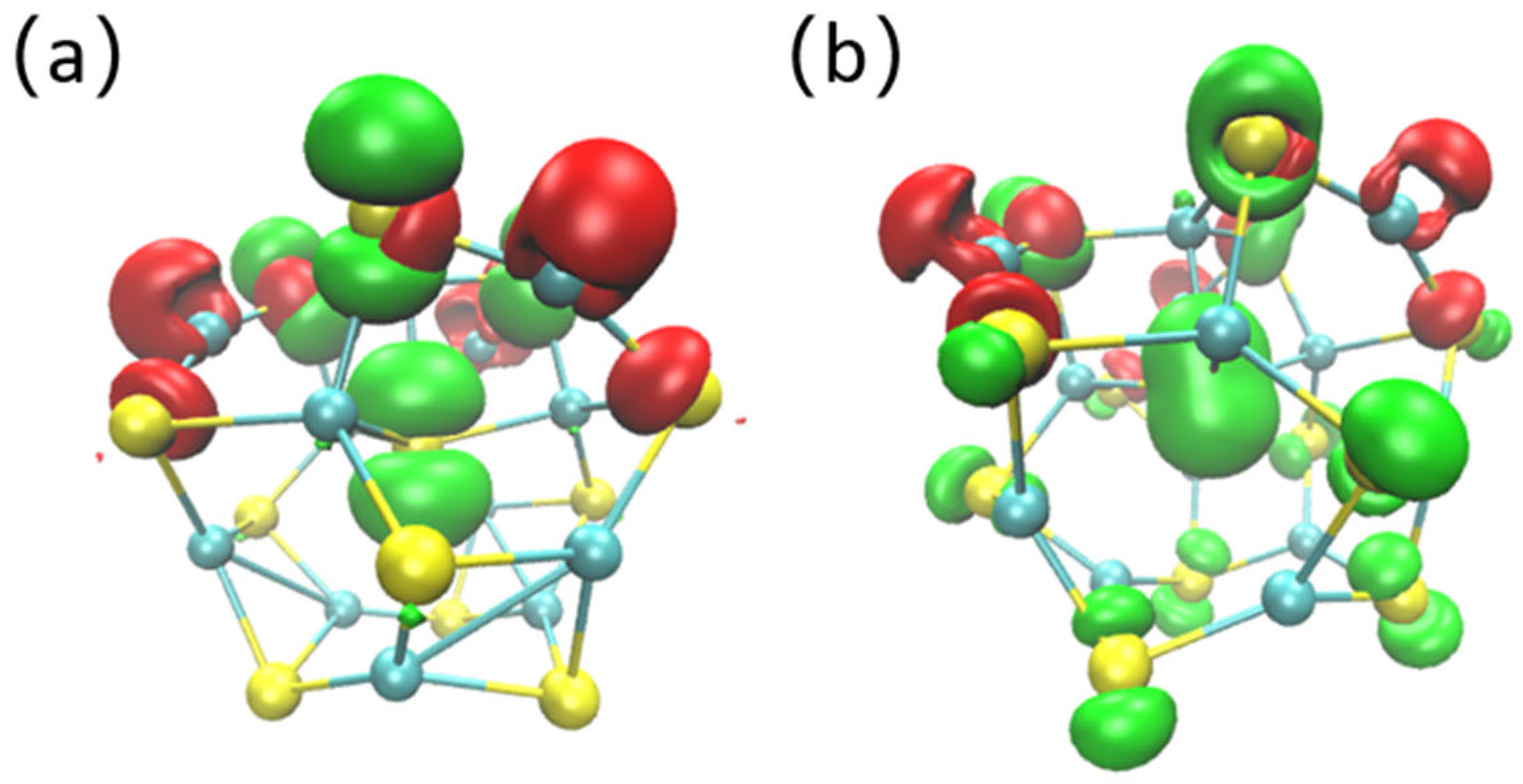

3.1. HOMO–LUMO Orbit Analysis

3.2. State of Density Analysis

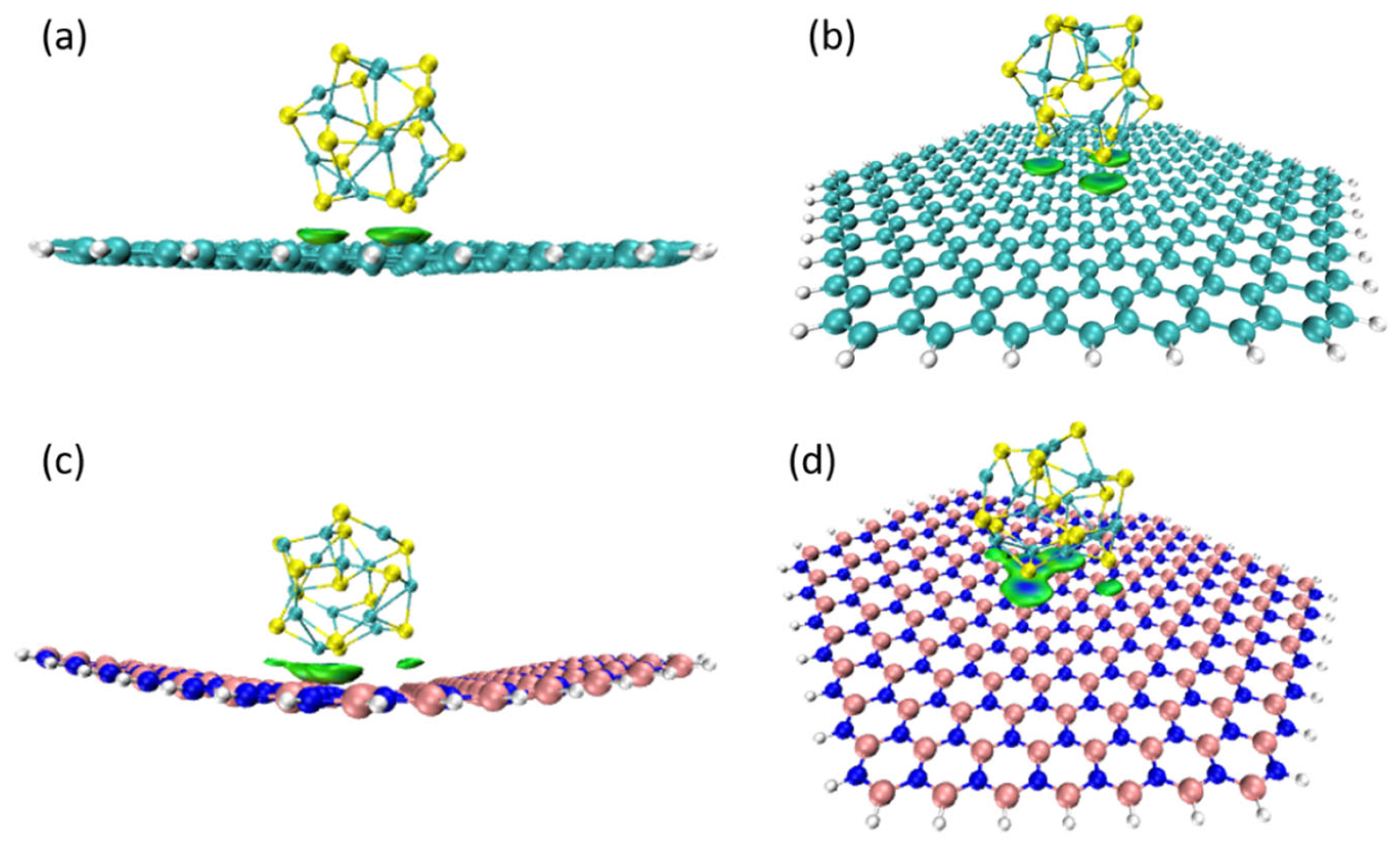

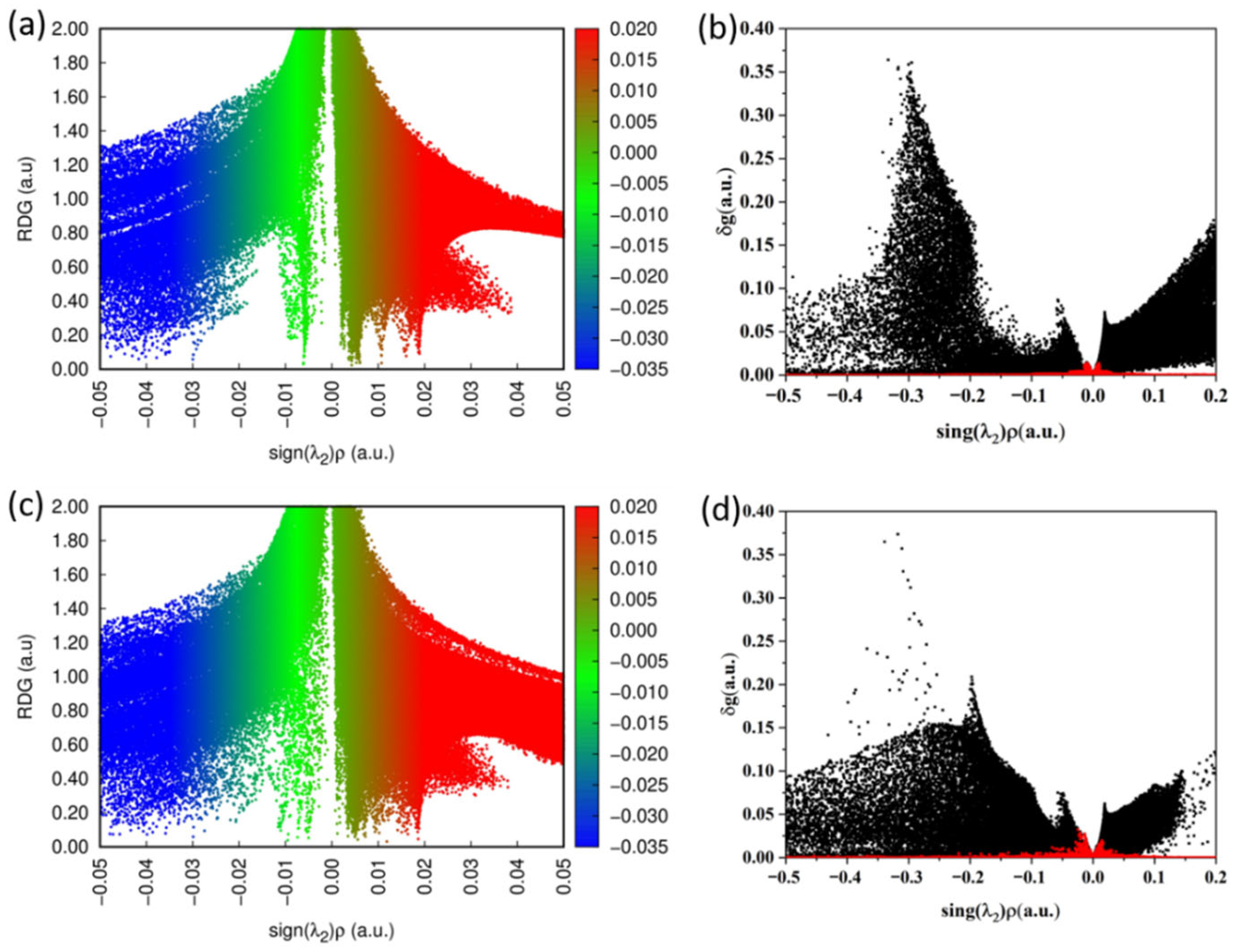

3.3. Weak Interaction Analysis

3.4. Binding Energy Analysis

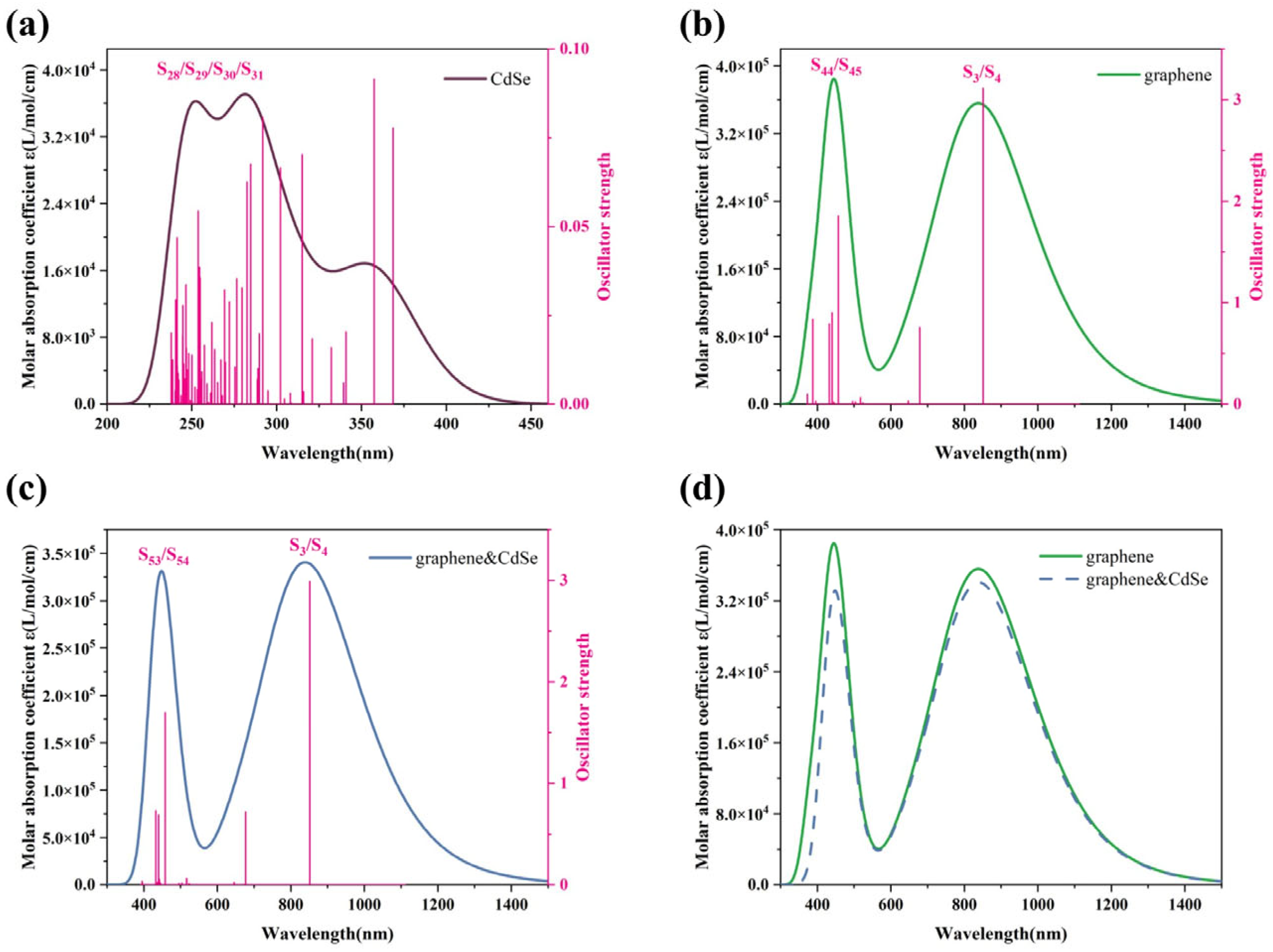

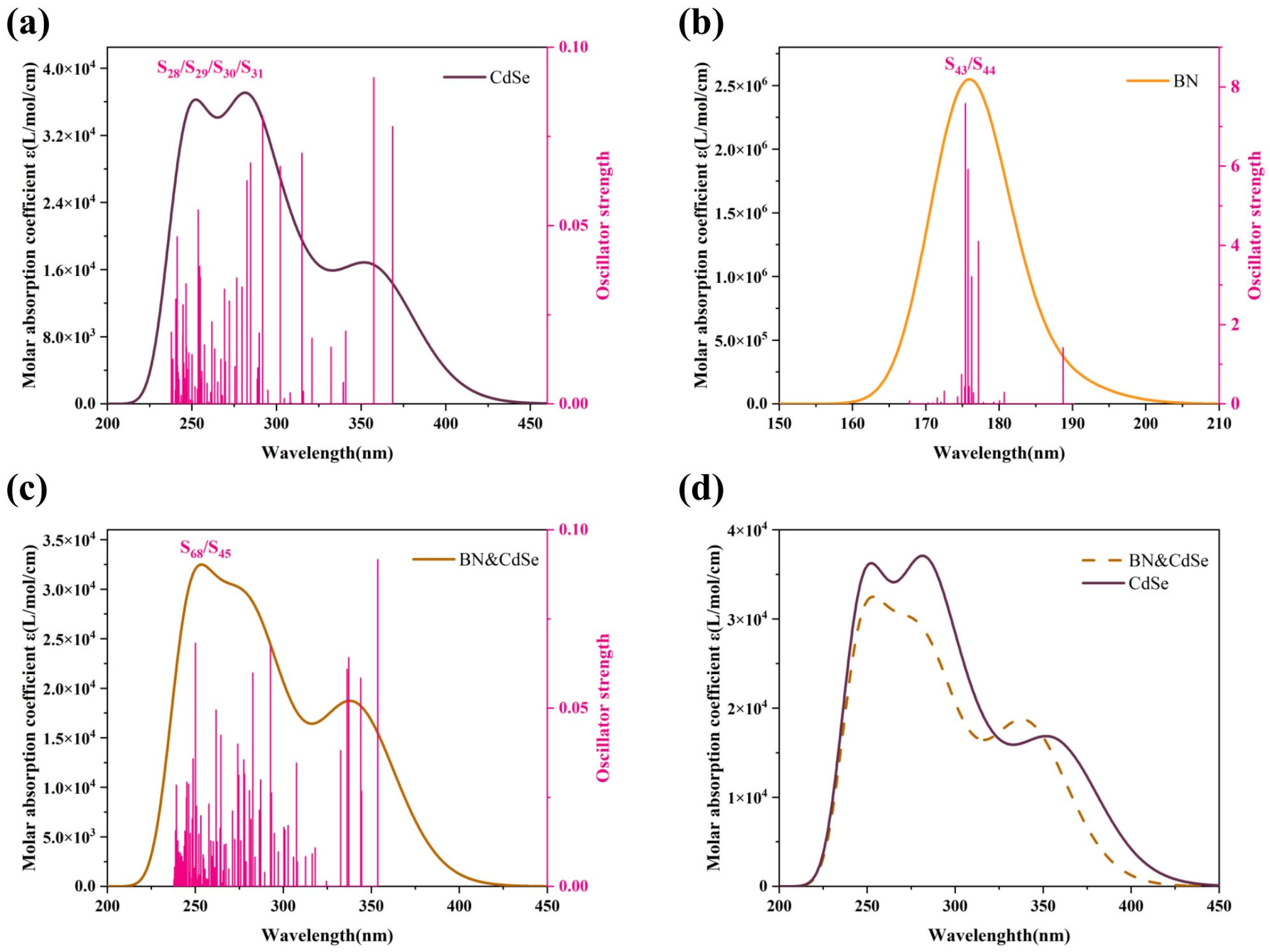

3.5. UV–Vis Absorption Spectrum Analysis

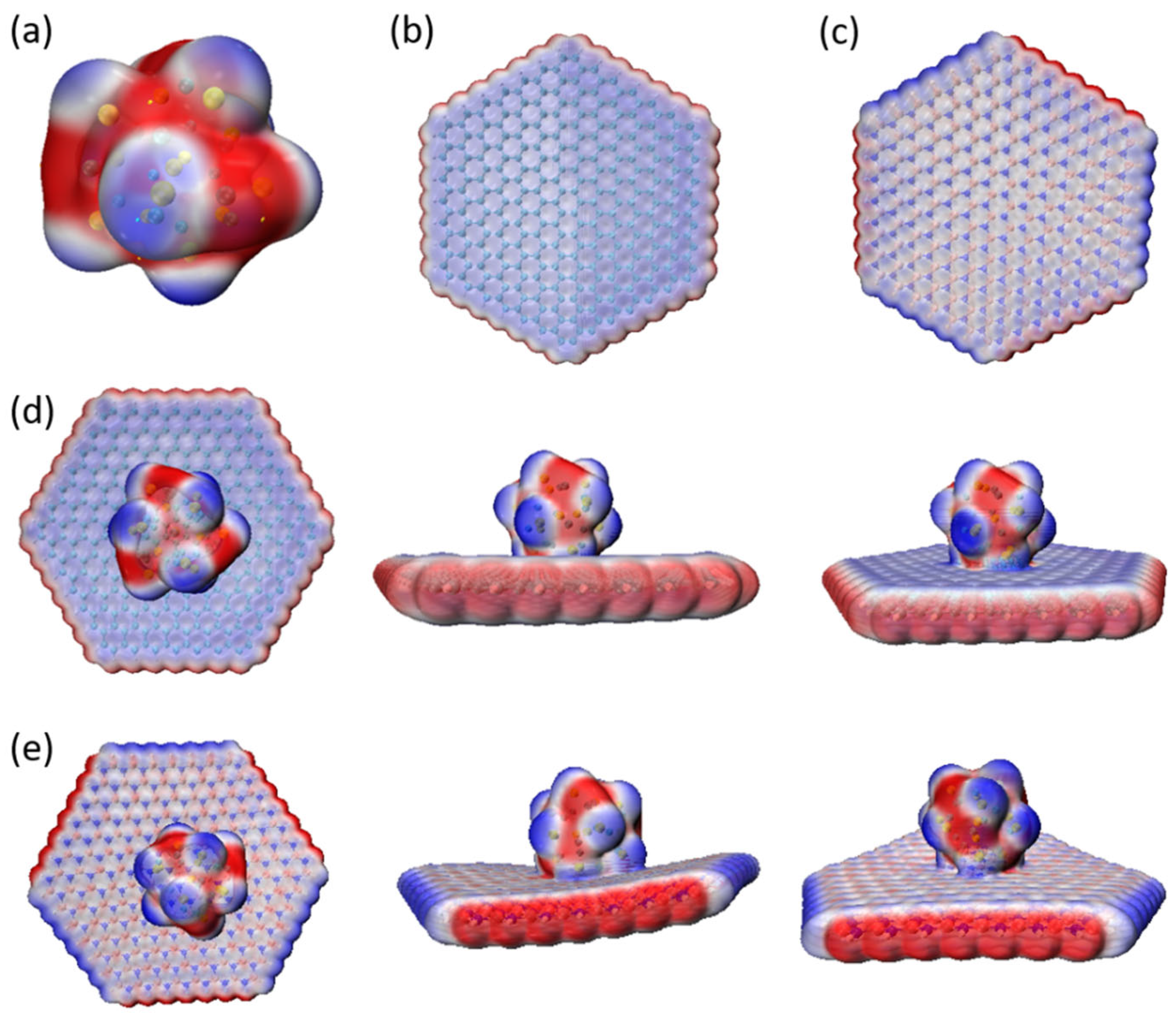

3.6. Electrostatic Potential Analysis

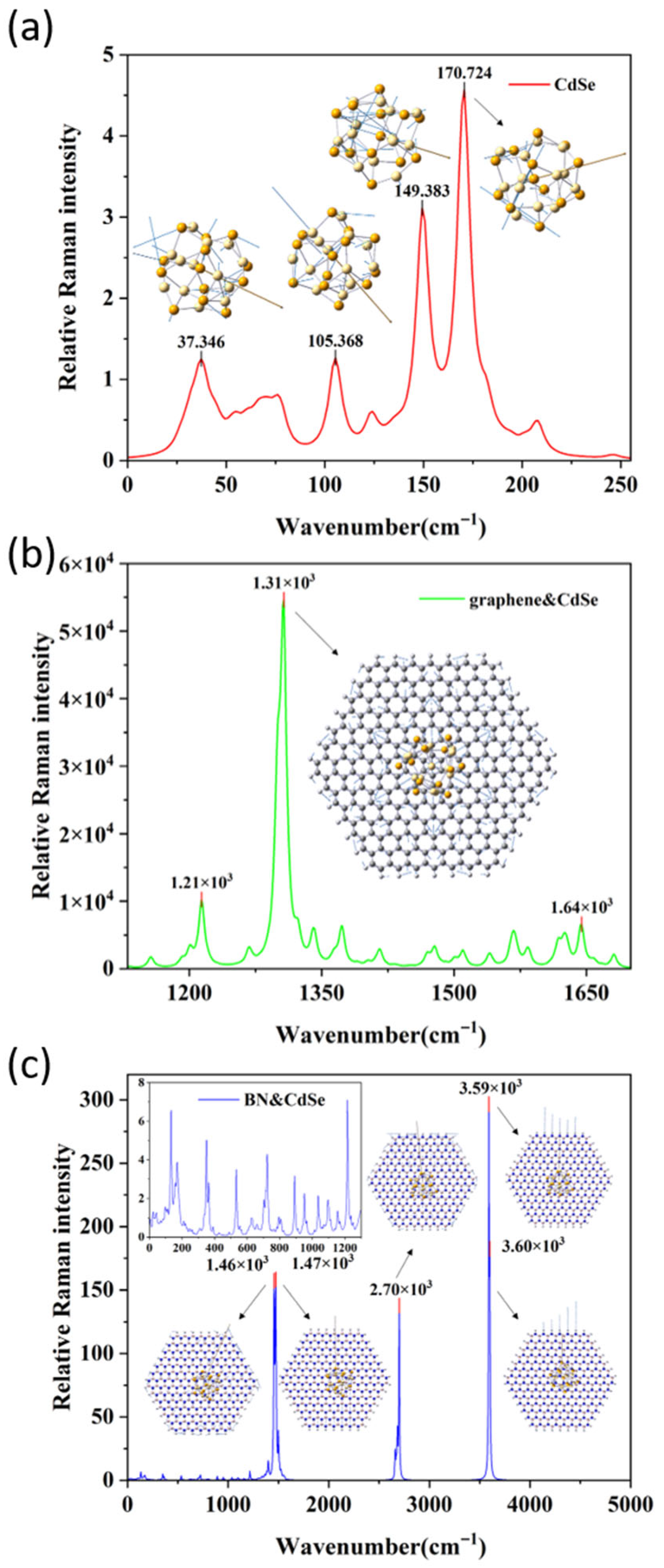

3.7. Raman Spectrum Analysis

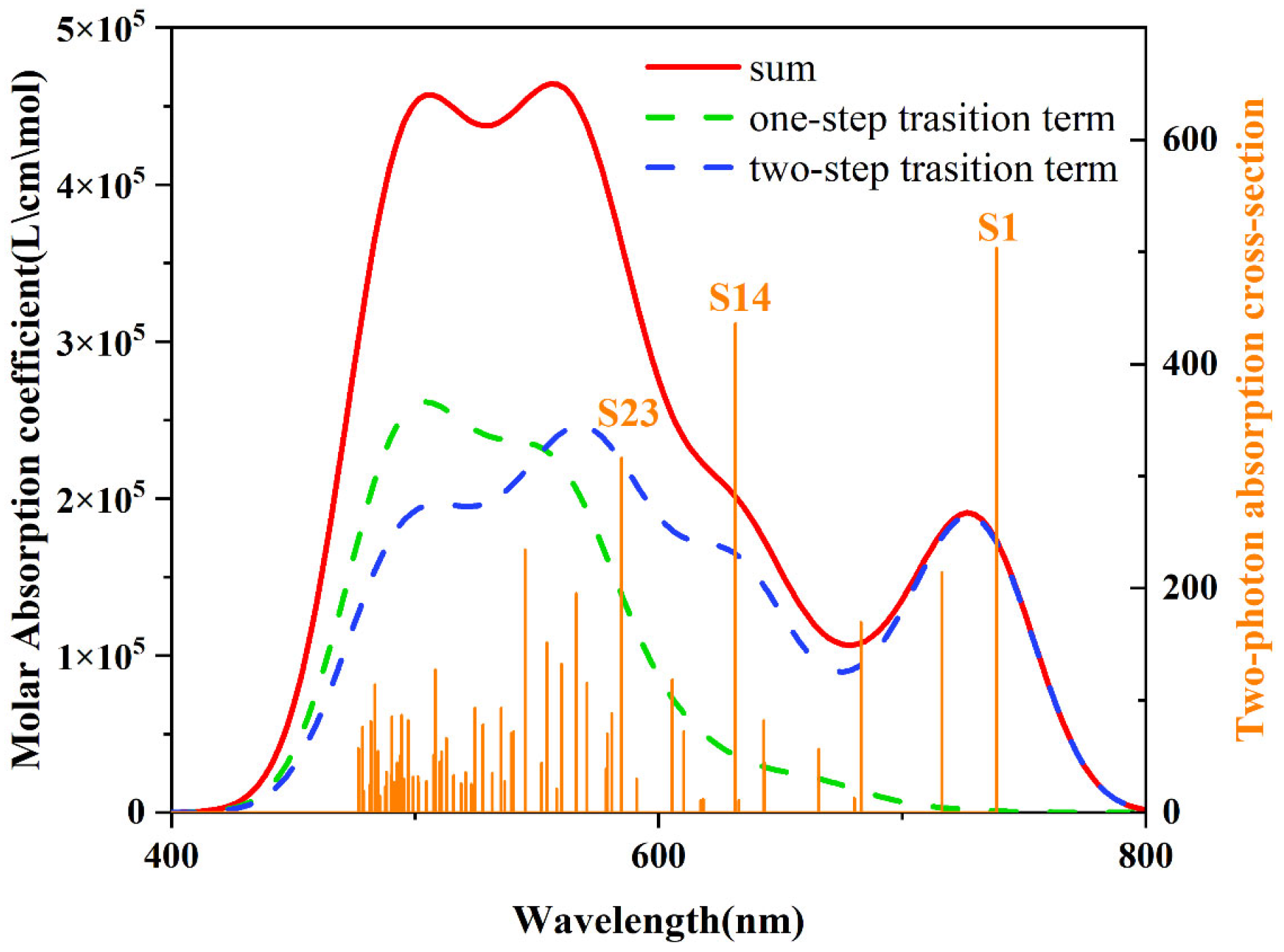

3.8. Two-Photon Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Z.; Gao, M.; Wu, W.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y.W.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Han, L.; et al. Recent advances in quantum dot-based light-emitting devices: Challenges and possible solutions. Mater. Today 2019, 24, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Arinze, E.S.; Palmquist, N.; Thon, S.M. Advancing colloidal quantum dot photovoltaic technology. Adv. Mater. 2016, 5, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahak, B.K.; Roshan, R.; Jhariya, N.; Sahu, A.; Patra, G.K.; Sahu, S.; Sahu, P.; Kumar, A. Study on photoinduced charge transfer between Citrus Limon capped CdS quantum dots with natural dyes. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 42, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetsch, F.; Zhao, N.; Kershaw, S.V.; Rogach, A.L. Quantum dot field effect transistors. Mater. Today 2013, 16, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, D. Improving the thermoelectric properties of graphene through zigzag graphene–graphyne nanoribbon heterostructures. Eur. Phys. J. B 2021, 94, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, S.; Mallick, S.; Bahadur, D. Electrochemical Method To Prepare Graphene Quantum Dots and Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8343–8353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorrata, S.; Balzarotti, R. Advances in Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shenoy, V.B. Graphene quantum dots embedded in hexagonal boron nitride sheets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 013105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Tong, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, J.; Qian, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. Hot spot assisted blinking suppression of CdSe quantum dots. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 652, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, D.; Li, X. Study of photoluminescence characteristics of CdSe quantum dots hybridized with Cu nanowires. Luminescence 2016, 31, 1298–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Ma, F.; Sun, M. Visualization of weak interactions between quantum dot and graphene in hybrid materials. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, F.; Sun, M. Charge-transfer channel in quantum dot–graphene hybrid materials. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 145202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Rev. C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016.

- BIOVIA Material Studio, Version 2021; Dassault Systèmes: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020.

- Dennington, R.; Todd, A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, Version 6; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2016.

- Kasuya, A.; Sivamohan, R.; Barnakov, Y.A.; Dmitruk, I.M.; Nirasawa, T.; Romanyuk, V.R.; Kumar, V.; Mamykin, S.V.; Tohji, K.; Jeyadevan, B.; et al. Ultra-stable nanoparticles of CdSe revealed from mass spectrometry. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassolov, V.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Pople, J.A.; Redfern, P.C.; Curtiss, L.A. 6-31G basis set for third-row atoms. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, R.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, G. Hexagonal WSe2 Nanoplates for Large-Scale Continuous Optoelectronic Films. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 5014–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejo-Alvaro, F.; Alfaro-López, H.M.; Salinas-Juárez, M.G.; Rojas-Chávez, H.; Cruz-Martínez, H.; Medina, D.I. Metal clusters/modified graphene composites with enhanced CO adsorption: A density functional theory approach. J. Nanopart. Res. 2022, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, R.K.; Ren, C.Y.; Chang, Y.C. Semi-Empirical Pseudopotential Method for Graphene and Graphene Nanoribbons. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, H.; Kawabata, H. Additions of fluorine atoms to the surfaces of graphene Nanoflakes: A density functional theory study. Solid State Sci. 2019, 97, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.K.U.; Kohn, W. Local Density-Functional Theory of Frequency-Dependent Linear Response. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, T.; Tew, D.P.; Handy, N.C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Su, N.Q.; Yang, W. Describing Chemical Reactivity with Frontier Molecular Orbitalets. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.C.M.; Bezerra, C.G.; Lawlor, J.A.; Ferreira, M.S. Density of states of helically symmetric boron carbon nitride nanotubes. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2014, 26, 015303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Zhan, H.; Du, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. DFT investigation of transition metal-doped graphene for the adsorption of HCl gas. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 136, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Si, W.; Liu, F.; et al. 0D/2D heterojunction of graphene quantum dots/MXene nanosheets for boosted hydrogen evolution reaction. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 30, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Zong, H.; Zhu, L.; Sun, M. External Electric Field-Dependent Photoinduced Charge Transfer in a Donor–Acceptor System in Two-Photon Absorption. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 2319–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, J.; Xu, H. Visualizations of transition dipoles, charge transfer, and electron-hole coherence on electronic state transitions between excited states for two-photon absorption. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 064106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CdSe | Graphene | Graphene/CdSe | CdSe | BN | BN/CdSe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Hartree) | −745.942 | −11,231.217 | −11,978.807 | −745.942 | −11,745.106 | −13,492.567 |

| Total binding energy | −4326.842 KJ/mol | −3988.134 KJ/mol | ||||

| Name | TPA cross section | TPA spectral line width | Gaussian spectrum broadening function | Transition probability | The electronic dipole moment |

| Physical meaning | A physical quantity that describes the ability of a material to absorb two photon in a two-photon absorption process, The larger the , the higher the two-phono absorption efficiency. | The frequency range at which a substance can absorb two photons in the two-photon absorption process in indicated. | It is used to describe spectral broadening and energy distribution to ensure that theoretical calculations agree with experimental results. | It is used to calculate the electron transition in two-photon absorption. | The asymmetry of charge distribution and the strength of photon-electron coupling are described, which determines the transition probability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Y.; Du, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, S. Symmetry-Guided Theoretical Study on Photoexcitation Characteristics of CdSe Quantum Dots Hybridized with Graphene and BN. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111972

Du Y, Du Z, Sun J, Wang J, Cao S. Symmetry-Guided Theoretical Study on Photoexcitation Characteristics of CdSe Quantum Dots Hybridized with Graphene and BN. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111972

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Yinuo, Zeng Du, Jianjun Sun, Junping Wang, and Shuo Cao. 2025. "Symmetry-Guided Theoretical Study on Photoexcitation Characteristics of CdSe Quantum Dots Hybridized with Graphene and BN" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111972

APA StyleDu, Y., Du, Z., Sun, J., Wang, J., & Cao, S. (2025). Symmetry-Guided Theoretical Study on Photoexcitation Characteristics of CdSe Quantum Dots Hybridized with Graphene and BN. Symmetry, 17(11), 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111972