Parameter Estimation of MSNBurr-Based Hidden Markov Model: A Simulation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Hidden Markov Model

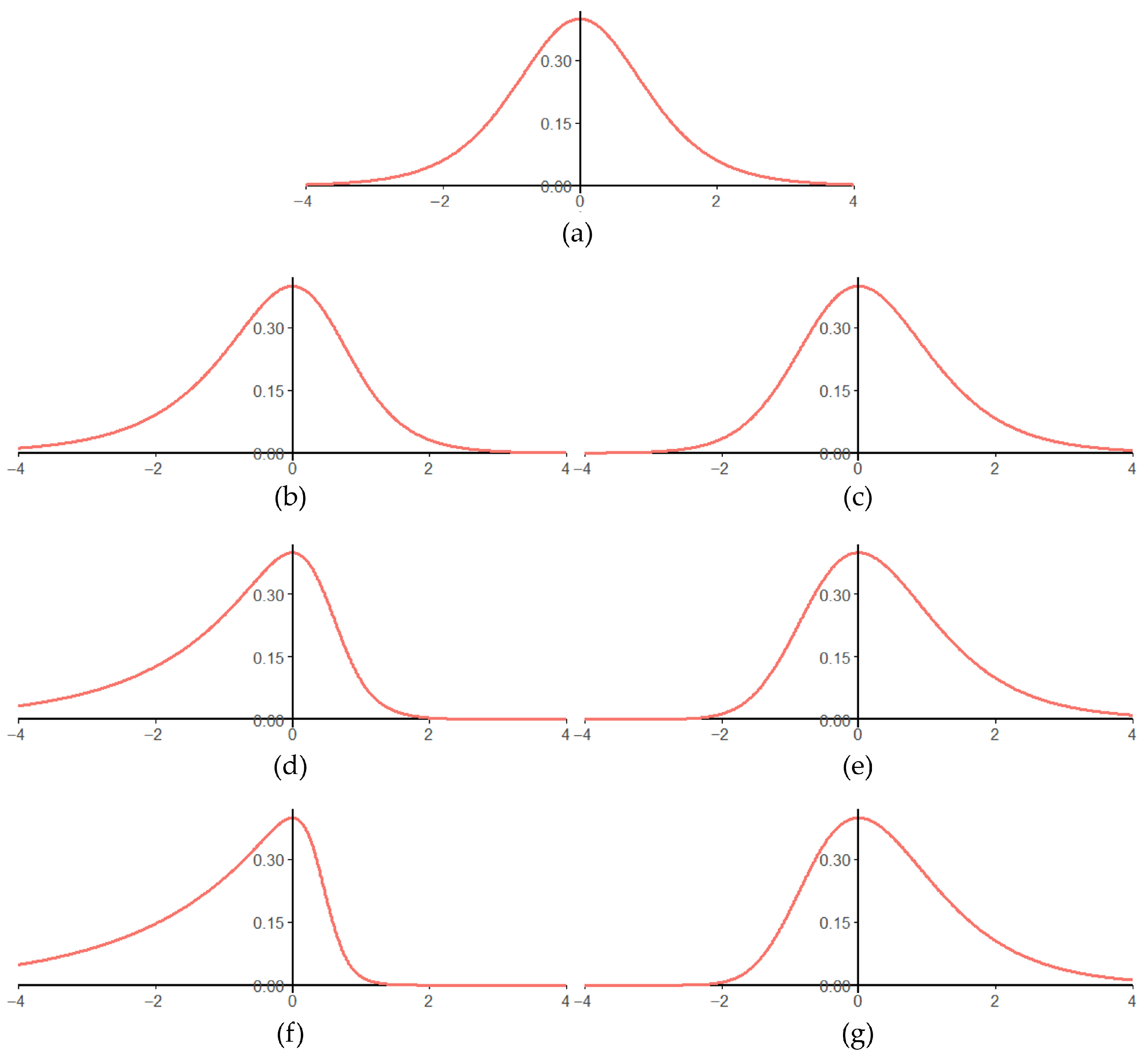

2.2. MSNBurr-Based HMM

2.3. Parameter Estimation of MSNBurr-HMM

| Algorithm 1. Baum–Welch algorithm for MSNBurr-HMM. |

| Input: ; Initialization ; convergence tolerance Output: Initialization: Set the iteration index Repeat: E-Step: Compute and using Equations (15), (16), (18) and (19). Compute and using Equations (20) and (21). , M-Step: Update using Equation (22) to obtain Update using Equation (23) to obtain Update using Equation (24) to obtain Convergence Check: Evaluate the parameter change using Equation (25) If the criterion in Equation (25) is satisfied, then stop the iteration and set ; Else set and repeat the process. End Repeat |

2.4. Simulation Design

2.5. Evaluation Criteria

3. Results

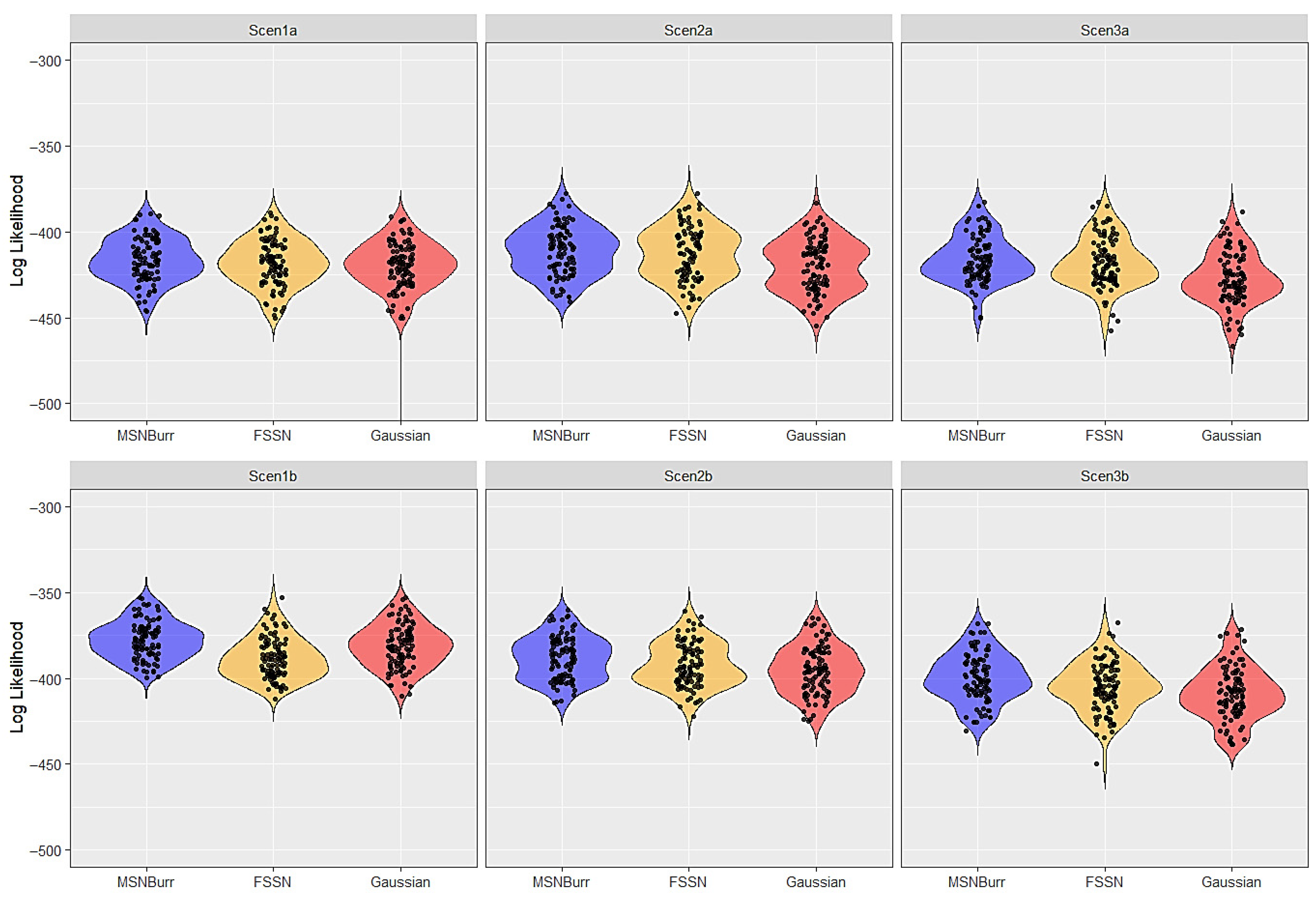

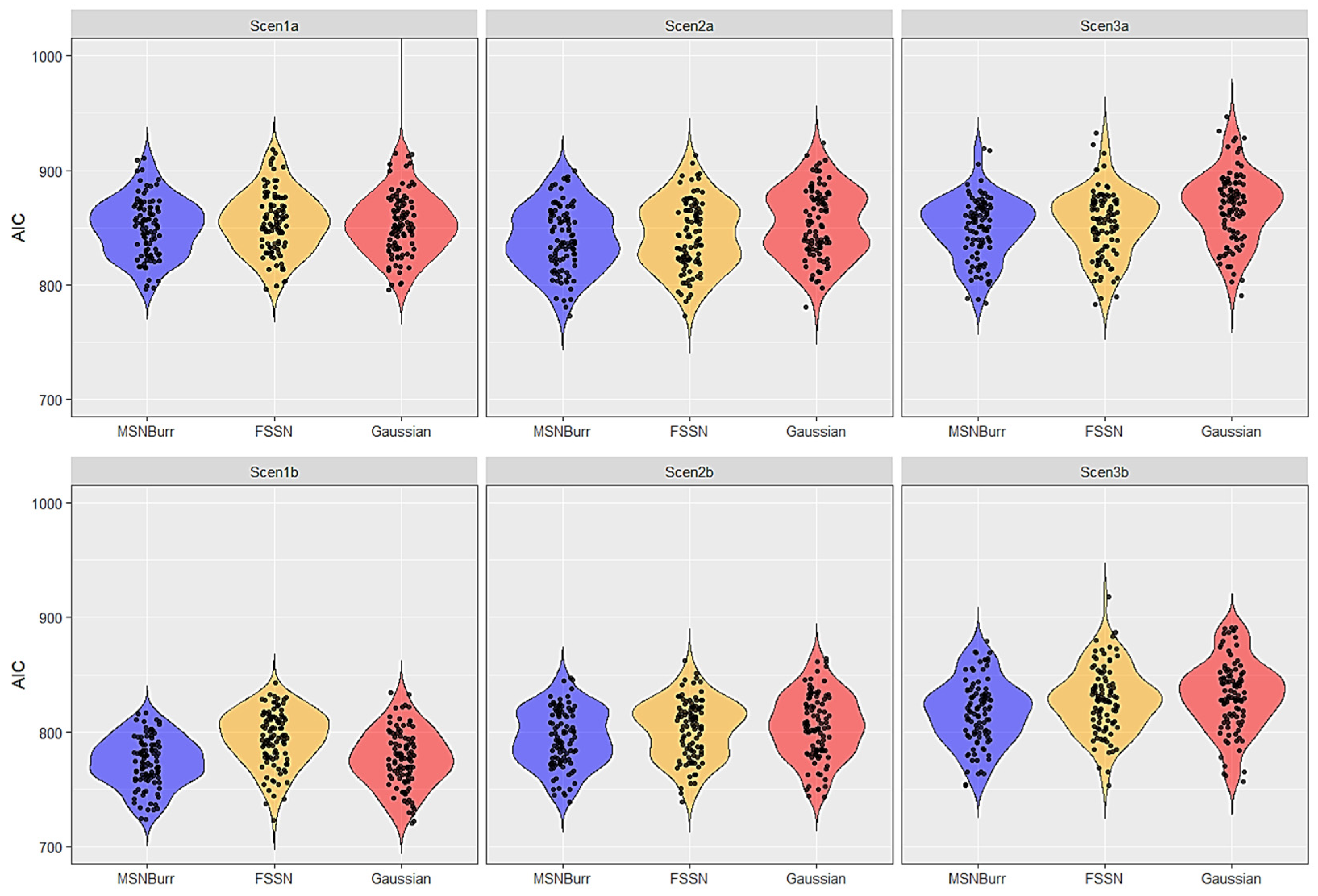

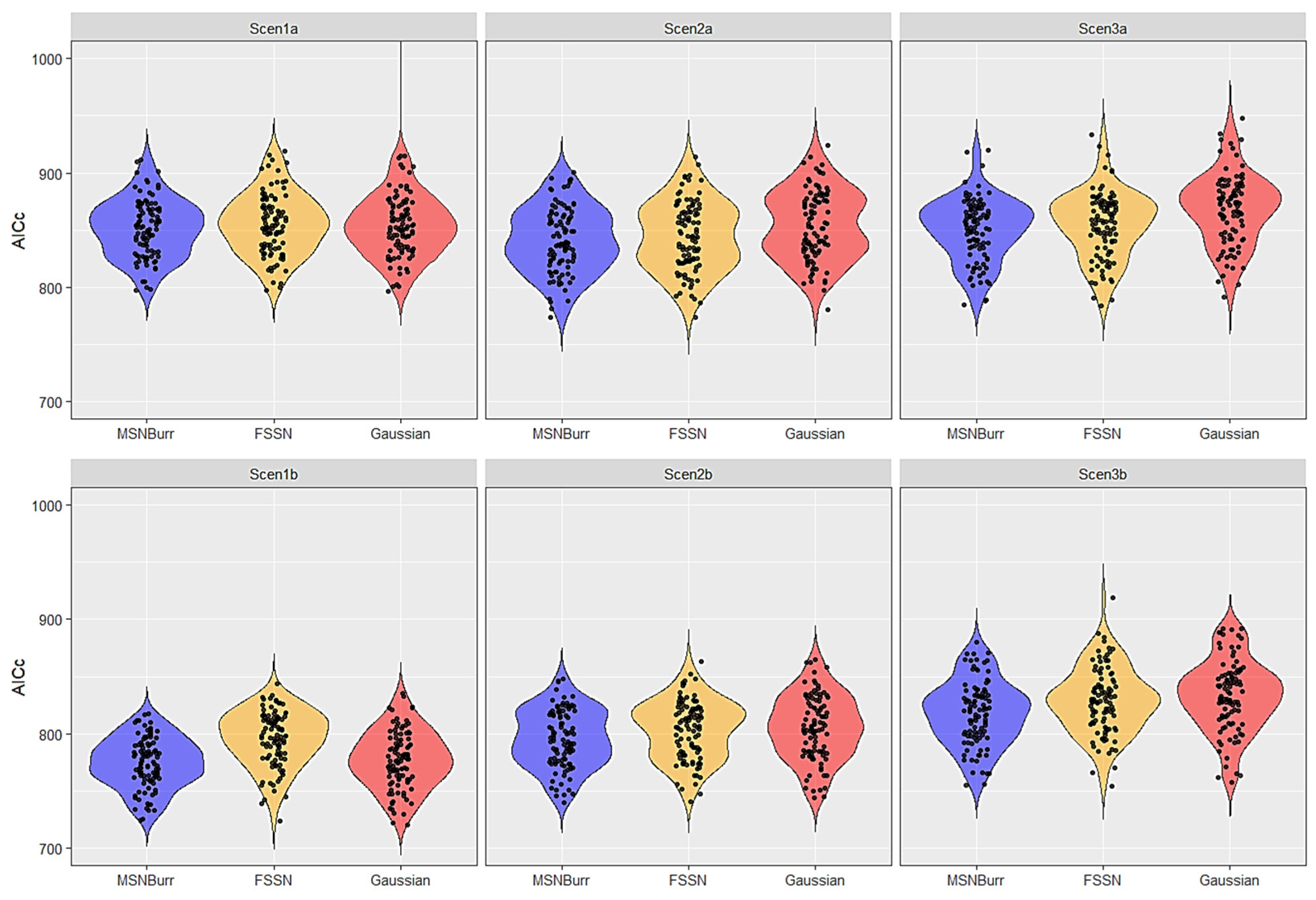

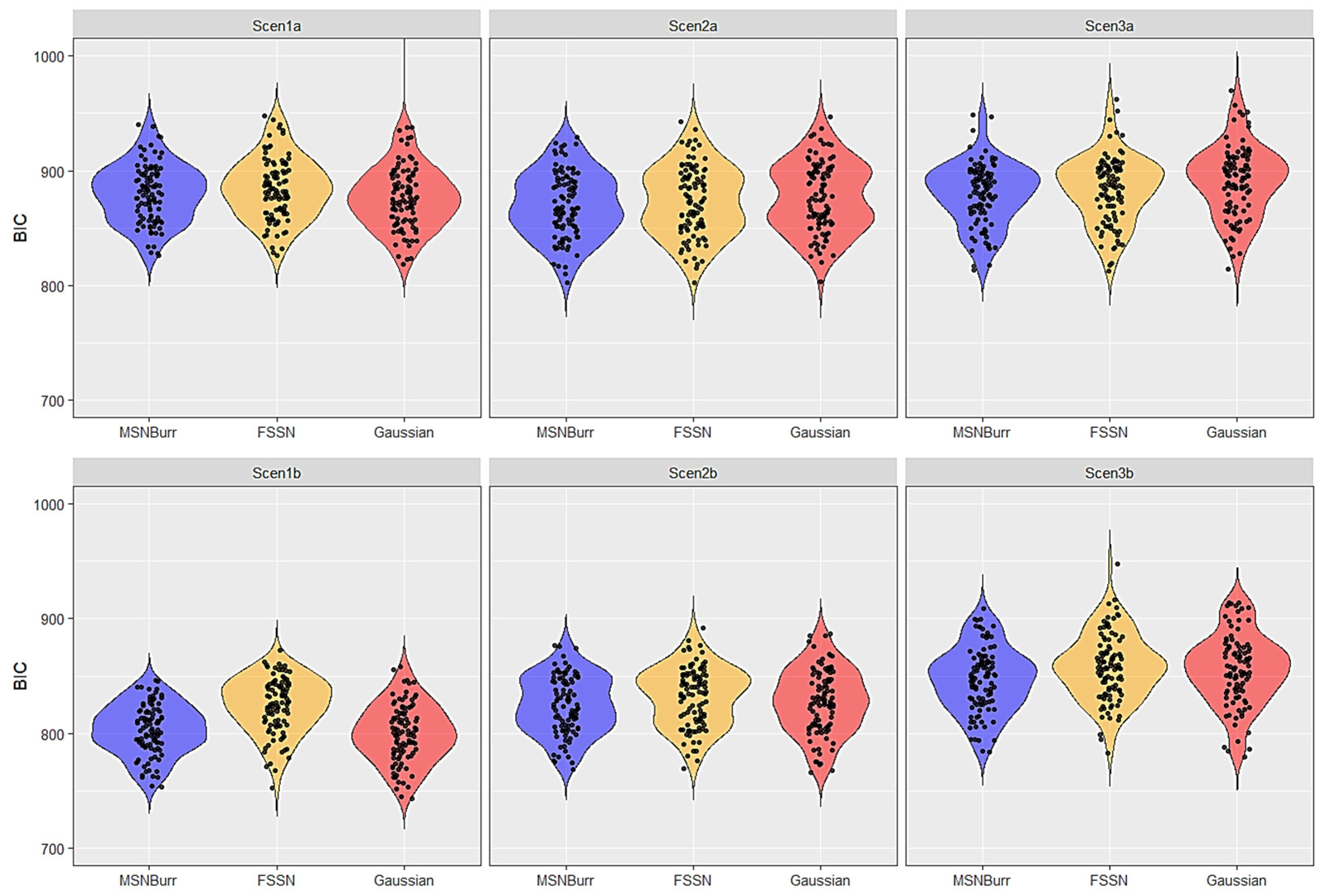

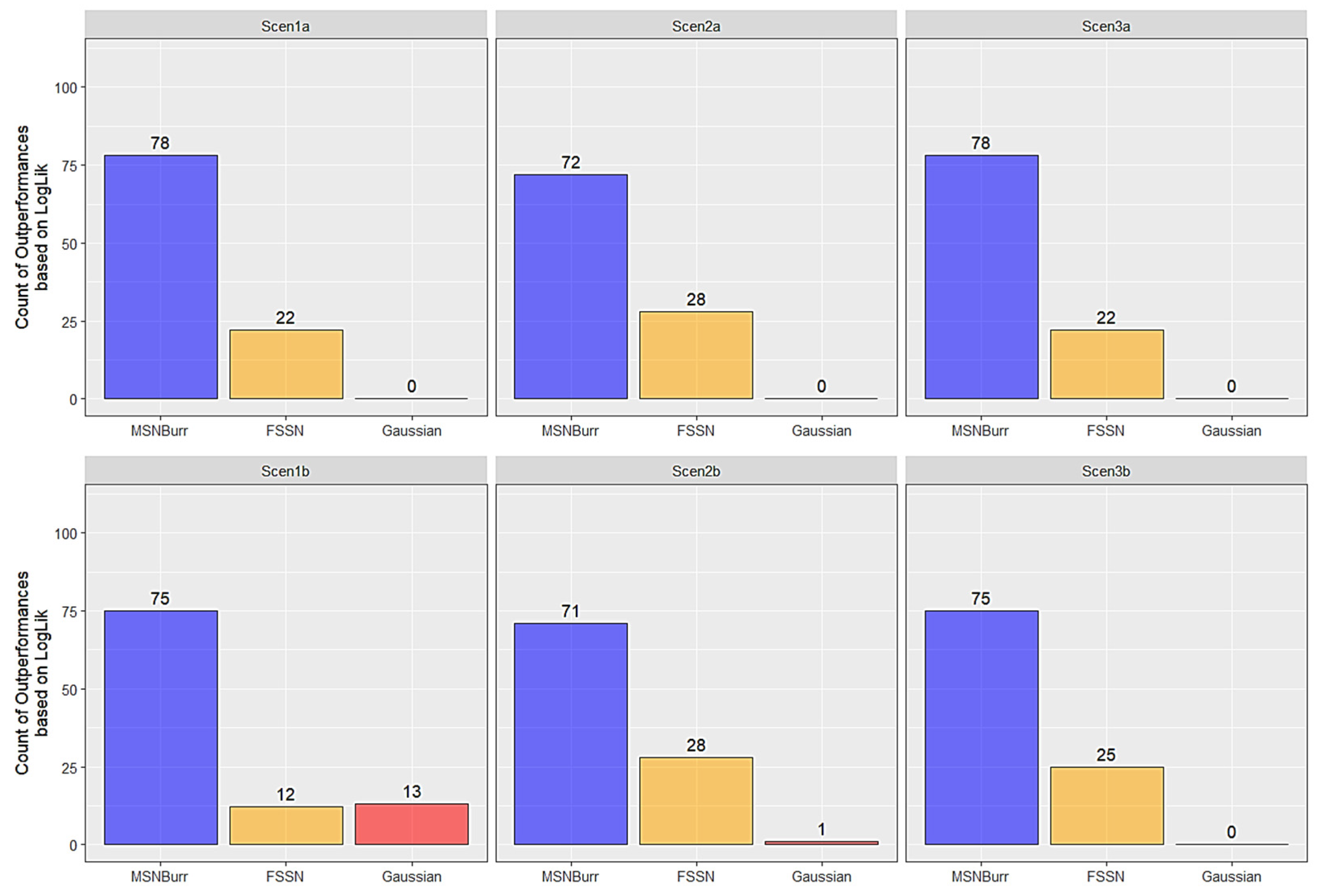

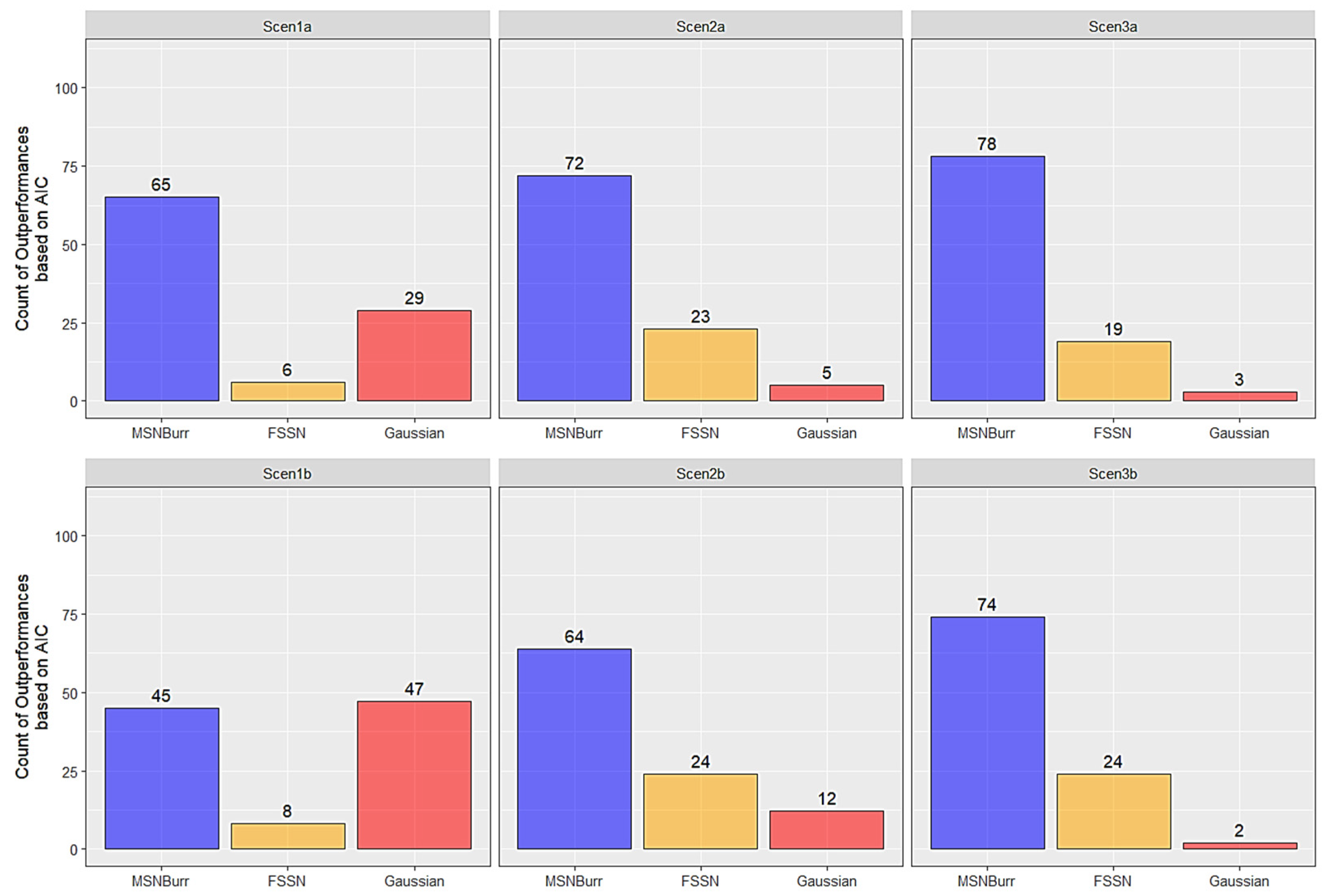

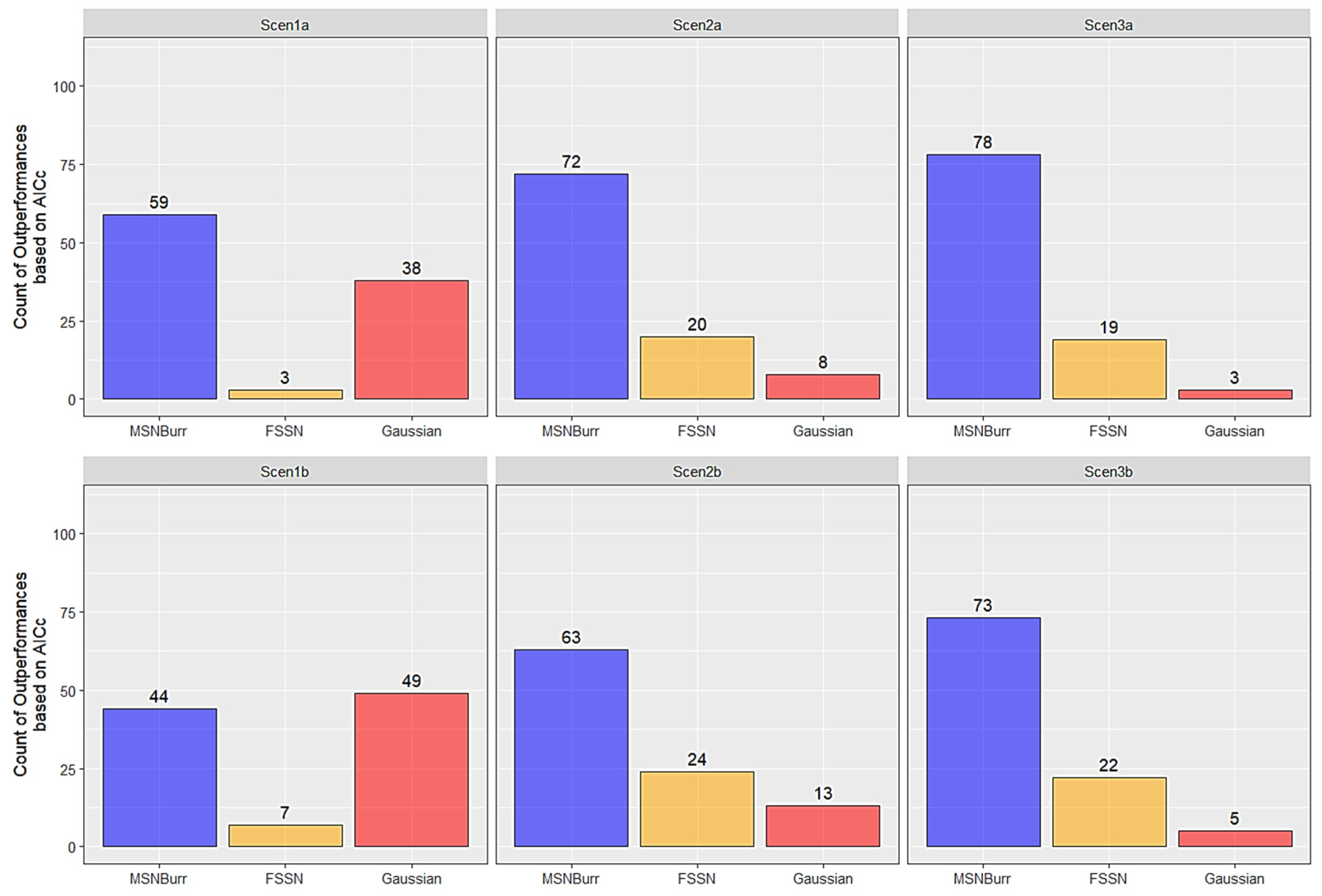

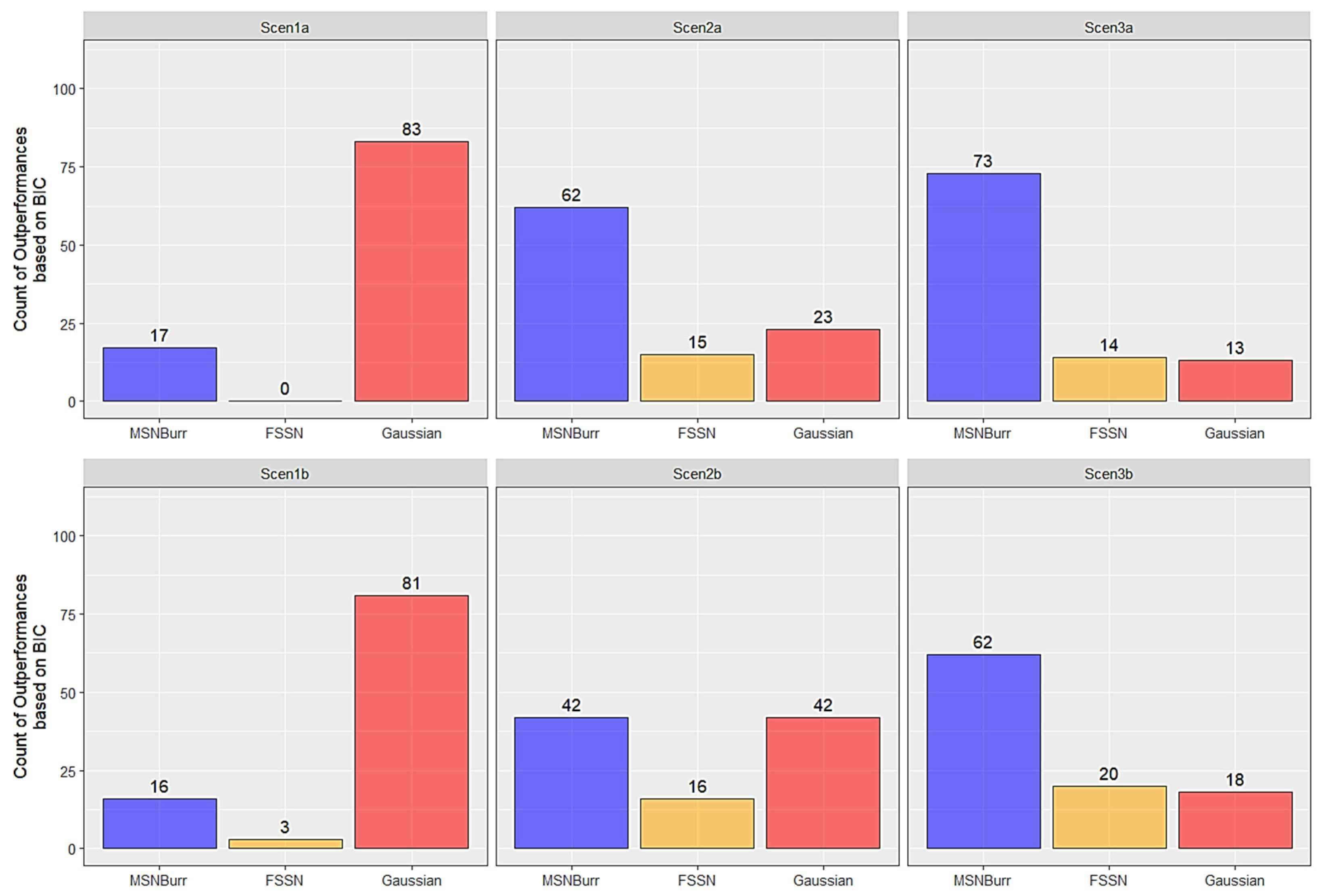

3.1. Simulation Results

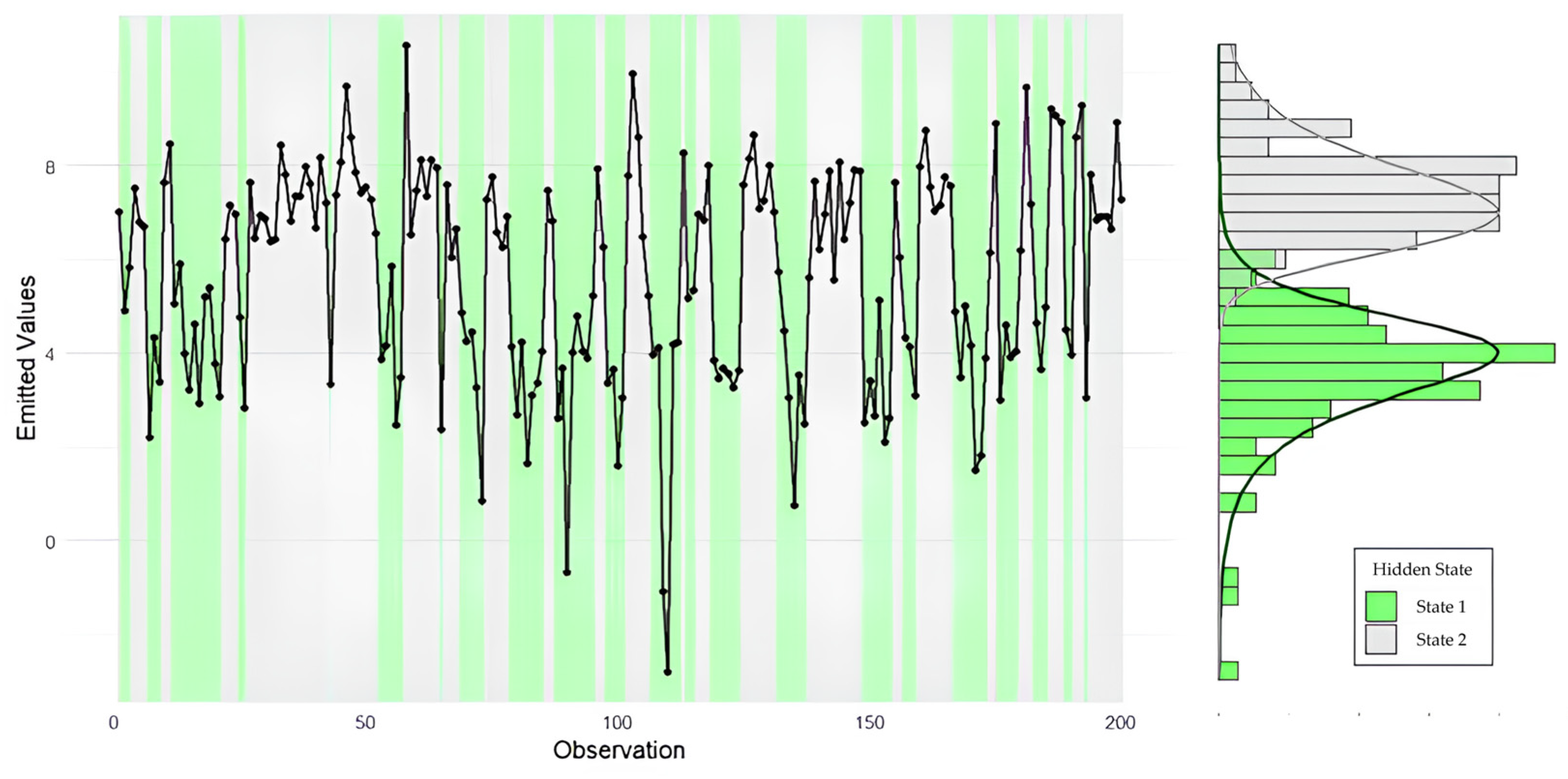

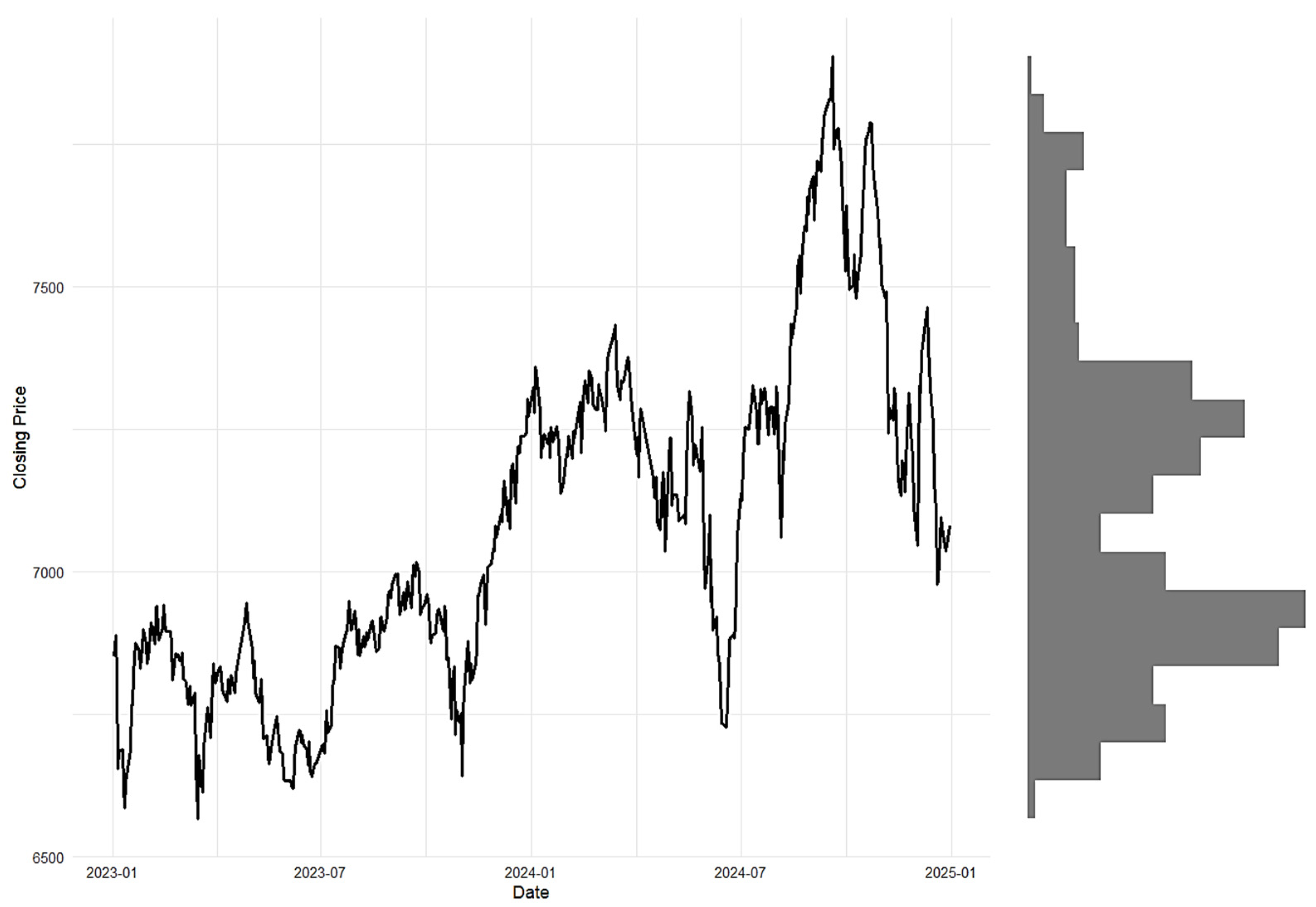

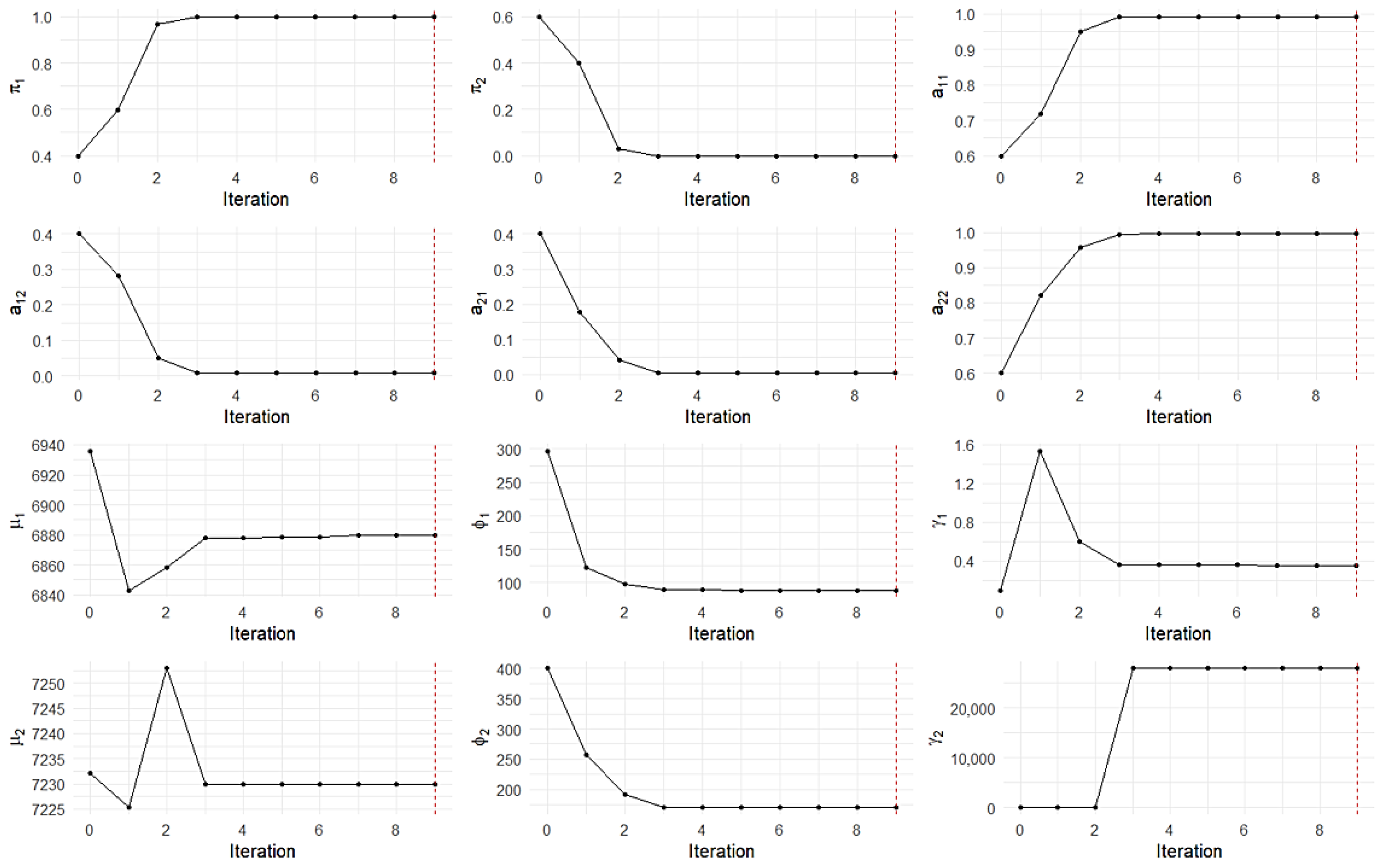

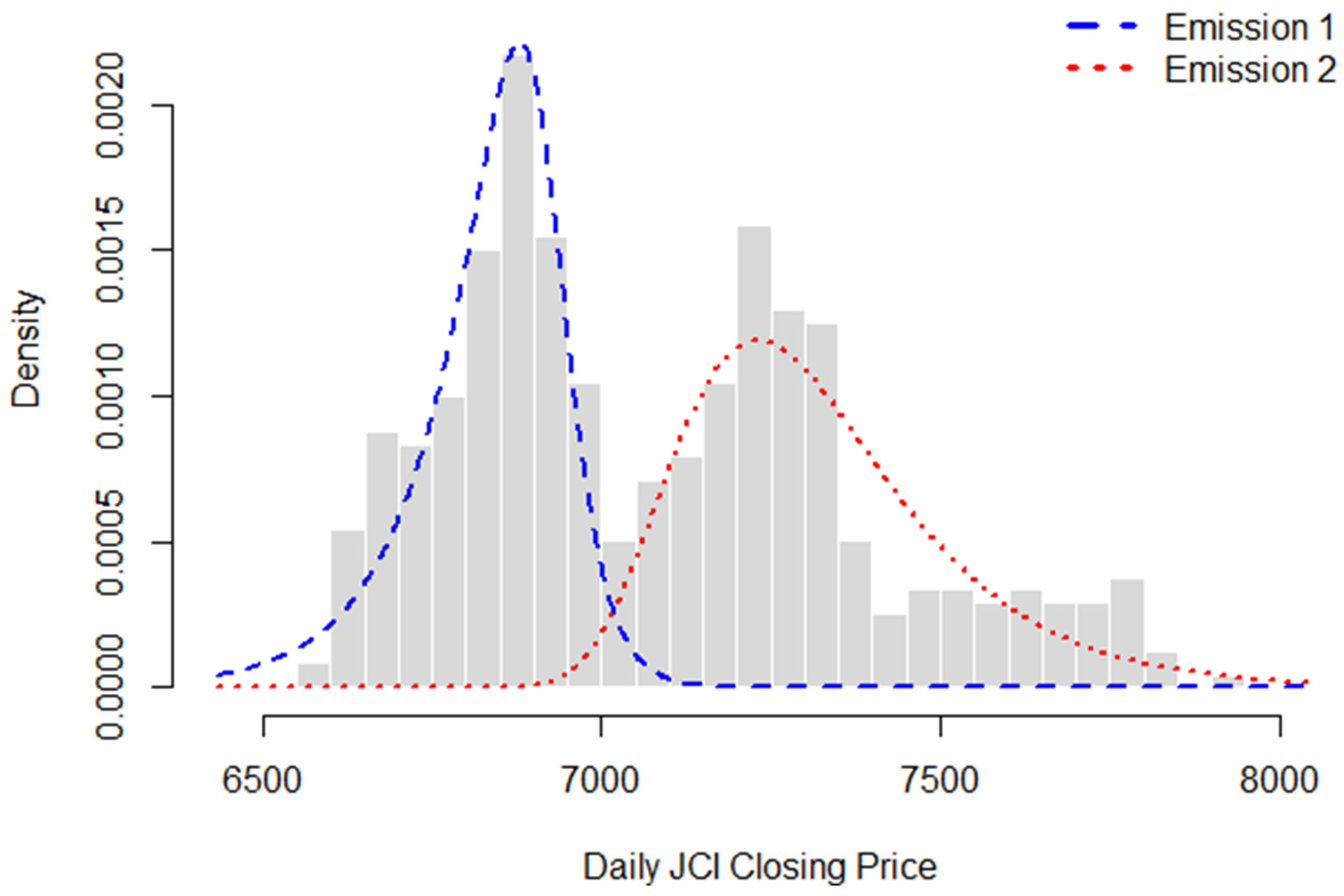

3.2. Real-Data Example

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Total number of observation periods | |

| Number of hidden states in the MSNBurr-HMM | |

| Observable value at time , for ; Full observation sequence | |

| Hidden state at time , for ; Full hidden state sequence | |

| Full parameter set of MSNBurr-HMM | |

| Initial state probability | |

| Transition probability matrix | |

| Emission parameter set | |

| Emission parameter set for i-th hidden state, , for | |

| Location parameter of the emission distribution in the i-th hidden state | |

| Scale parameter of the emission distribution in the i-th hidden state | |

| Shape parameter of the emission distribution in the i-th hidden state | |

| Forward variable, for and | |

| Backward variable, for and | |

| Expected state occupancy, for and | |

| Expected state transition, for and | |

| Iteration index of the BWA | |

| Convergence tolerance |

References

- Yu, S.-Z. Hidden Semi-Markov Models. Artif. Intell. 2010, 174, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouemou, G.L. History and Theoretical Basics of Hidden Markov Models. In Hidden Markov Models, Theory and Applications; Dymarski, P., Ed.; InTech: Houston, TX, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-953-307-208-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bouarada, O.; Azam, M.; Amayri, M.; Bouguila, N. Hidden Markov Models with Multivariate Bounded Asymmetric Student’s t-Mixture Model Emissions. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2024, 27, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, B.; Garhwal, S.; Kumar, A. A Systematic Review of Hidden Markov Models and Their Applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Shree, R.; Shukla, A.K.; Pandey, R.P.; Shukla, V.; Pandey, D. A Feature Based Classification and Analysis of Hidden Markov Model in Speech Recognition. In Cyber Intelligence and Information Retrieval; Tavares, J.M.R.S., Dutta, P., Dutta, S., Samanta, D., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 291, pp. 365–379. ISBN 978-981-16-4283-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bhar, R.; Hamori, S. Hidden Markov Models: Applications to Financial Economics; Advanced Studies in Theoretical and Applied Econometrics; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 40, ISBN 978-1-4020-7899-6. [Google Scholar]

- Glennie, R.; Adam, T.; Leos-Barajas, V.; Michelot, T.; Photopoulou, T.; McClintock, B.T. Hidden Markov Models: Pitfalls and Opportunities in Ecology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.-J. Hidden Markov Models and Their Applications in Biological Sequence Analysis. Curr. Genom. 2009, 10, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, S.B.; Killen, B.; Cummins, L.; Rahimi, S.; Amirlatifi, A.; Seale, M. A Survey of HMM-Based Algorithms in Machinery Fault Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Orlando, FL, USA, 5–7 December 2021; IEEE: Orlando, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Volant, S.; Bérard, C.; Martin-Magniette, M.-L.; Robin, S. Hidden Markov Models with Mixtures as Emission Distributions. Stat. Comput. 2014, 24, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowan, B.; Zhang, L.; Matar, N.; Zraqou, J.; Omar, F.; Alnatsheh, A. A Novel Lift Adjustment Methodology for Improving Association Rule Interpretation. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 15, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, C.S.K.; Behera, A.K.; Dehuri, S.; Ghosh, A. An Outliers Detection and Elimination Framework in Classification Task of Data Mining. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective; Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning Series; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-262-01802-9. [Google Scholar]

- Iriawan, N. Computationally Intensive Approaches to Inference in Neo-Normal Linear Models. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Choir, A.S.; Iriawan, N.; Ulama, B.S.S.; Dokhi, M. MSEPBurr Distribution: Properties and Parameter Estimation. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 2019, 15, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzalini, A. A Class of Distributions Which Includes the Normal Ones. Scand. J. Stat. 1985, 12, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Azzalini, A.; Capitanio, A. Distributions Generated by Perturbation of Symmetry with Emphasis on a Multivariate Skew T-Distribution. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2003, 65, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, B. The Modality of Skew T-Distribution. Stat. Pap. 2023, 64, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravitasari, A.A.; Iriawan, N.; Fithriasari, K.; Purnami, S.W.; Irhamah; Ferriastuti, W. A Bayesian Neo-Normal Mixture Model (Nenomimo) for MRI-Based Brain Tumor Segmentation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasyid, D.A.; Iriawan, N.; Mashuri, M. On the Flexible Neo-Normal MSAR MSN-Burr Control Chart in Air Quality Monitoring. Air Soil Water Res. 2024, 17, 11786221241272391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraini, U.S.; Iriawan, N.; Fithriasari, K.; Hidayat, T. Ising Neo-Normal Model (INNM) for Segmentation of Cardiac Ultrasound Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2024 Beyond Technology Summit on Informatics International Conference (BTS-I2C), Jember, Indonesia, 19 December 2024; IEEE: Jember, Indonesia, 2024; pp. 298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, L.R. Hidden Markov Models and the Baum-Welch Algorithm. IEEE Inf. Theory Soc. Newsl. 2003, 53, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike, H. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvich, C.M.; Tsai, C.-L. Regression and Time Series Model Selection in Small Samples. Biometrika 1989, 76, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.; Steel, M.F.J. On Bayesian Modeling of Fat Tails and Skewness. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1998, 93, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, N.O.; Gómez, H.W.; Leiva, V.; Sanhueza, A. On the Fernández–Steel Distribution: Inference and Application. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2011, 55, 2951–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantini, D.; Iriawan, N.; Irhamah. Fernandez–Steel Skew Normal Conditional Autoregressive (FSSN CAR) Model in Stan for Spatial Data. Symmetry 2021, 13, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, L.R. A Tutorial on Hidden Markov Models and Selected Applications in Speech Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Xia, T.; Pan, E. Hidden Markov Model with Auto-Correlated Observations for Remaining Useful Life Prediction and Optimal Maintenance Policy. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 184, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, L.E.; Petrie, T.; Soules, G.; Weiss, N. A Maximization Technique Occurring in the Statistical Analysis of Probabilistic Functions of Markov Chains. Ann. Math. Stat. 1970, 41, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Balakrishnan, S.; Wainwright, M.J. Statistical and Computational Guarantees for the Baum-Welch Algorithm. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 18, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nirmal, A.; Jayaswal, D.; Kachare, P.H. A Hybrid Bald Eagle-Crow Search Algorithm for Gaussian Mixture Model Optimisation in the Speaker Verification Framework. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 10, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A. When to Use the Bonferroni Correction. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2014, 34, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario | Target of Emission Distribution | Median of Empirical Skewness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hidden State 1 | Hidden State 2 | Hidden State 1 | Hidden State 2 | |

| Scen1a | MSNBurr(2, 1, 1) | MSNBurr(10, 1, 1) | −0.0159 | 0.0584 |

| Scen1b | MSNBurr(4, 1, 1) | MSNBurr(7, 1, 1) | −0.0110 | −0.0834 |

| Scen2a | MSNBurr(2, 1, 1) | MSNBurr(10, 1, 5) | −0.0466 | 0.8220 |

| Scen2b | MSNBurr(4, 1, 1) | MSNBurr(7, 1, 5) | −0.0929 | 0.8865 |

| Scen3a | MSNBurr(2, 1, 0.5) | MSNBurr(10, 1, 5) | −0.6443 | 0.8058 |

| Scen3b | MSNBurr(4, 1, 0.5) | MSNBurr(7, 1, 5) | −0.7681 | 0.8264 |

| Iterations to Convergence | Scen1a | Scen1b | Scen2a | Scen2b | Scen3a | Scen3b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below 11 Iterations | 81 | 0 | 95 | 1 | 100 | 0 |

| 11–25 Iterations | 19 | 5 | 4 | 34 | 0 | 54 |

| 26–50 Iterations | 0 | 64 | 1 | 48 | 0 | 41 |

| Above 50 Iterations | 0 | 31 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 5 |

| Parameter | Scen1a | Scen1b | Scen2a | Scen2b | Scen3a | Scen3b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Est. | Target | Est. | Target | Est. | Target | Est. | Target | Est. | Target | Est. | |

| 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.52 | |

| 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.48 | |

| 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.71 | |

| 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.29 | |

| 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.80 | |

| 2.00 | 1.98 | 4.00 | 3.99 | 2.00 | 2.01 | 4.00 | 4.02 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 4.00 | 4.02 | |

| 10.00 | 9.98 | 7.00 | 6.96 | 10.00 | 9.99 | 7.00 | 6.98 | 10.00 | 10.01 | 7.00 | 7.00 | |

| 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | |

| 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | |

| 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.48 | |

| 1.00 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 5.00 | 5.82 | 5.00 | 6.68 | 5.00 | 5.99 | 5.00 | 6.15 | |

| Scenario | Model | Log-Likelihood | AIC | AICc | BIC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Scen1a | MSNBurr-HMM | −416.93 | 18.77 | 851.86 | 37.54 | 852.81 | 37.54 | 881.55 | 37.54 |

| FSSN-HMM | −417.58 | 18.91 | 853.16 | 37.81 | 854.11 | 37.81 | 882.85 | 37.81 | |

| Gaussian-HMM | −418.80 | 18.80 | 851.59 | 37.60 | 852.18 | 37.60 | 874.68 | 37.60 | |

| Scen1b | MSNBurr-HMM | −377.61 | 14.68 | 773.22 | 29.36 | 774.17 | 29.36 | 802.91 | 29.36 |

| FSSN-HMM | −389.26 | 17.44 | 796.52 | 34.88 | 797.47 | 34.88 | 826.21 | 34.88 | |

| Gaussian-HMM | −381.23 | 17.51 | 776.46 | 35.02 | 777.04 | 35.02 | 799.54 | 35.02 | |

| Scen2a | MSNBurr-HMM | −409.68 | 19.91 | 837.37 | 39.83 | 838.32 | 39.83 | 867.05 | 39.83 |

| FSSN-HMM | −412.32 | 21.94 | 842.65 | 43.89 | 843.60 | 43.89 | 872.33 | 43.89 | |

| Gaussian-HMM | −418.89 | 22.74 | 851.79 | 45.47 | 852.37 | 45.47 | 874.88 | 45.47 | |

| Scen2b | MSNBurr-HMM | −387.66 | 20.52 | 793.32 | 41.04 | 794.27 | 41.04 | 823.00 | 41.04 |

| FSSN-HMM | −393.53 | 19.35 | 805.06 | 38.69 | 806.01 | 38.69 | 834.75 | 38.69 | |

| Gaussian-HMM | −395.10 | 21.37 | 804.19 | 42.75 | 804.78 | 42.75 | 827.28 | 42.75 | |

| Scen3a | MSNBurr-HMM | −417.50 | 17.04 | 852.99 | 34.09 | 853.94 | 34.09 | 882.68 | 34.09 |

| FSSN-HMM | −419.76 | 19.65 | 857.52 | 39.29 | 858.47 | 39.29 | 887.21 | 39.29 | |

| Gaussian-HMM | −429.20 | 21.37 | 872.41 | 42.75 | 872.99 | 42.75 | 895.49 | 42.75 | |

| Scen3b | MSNBurr-HMM | −400.67 | 18.10 | 819.34 | 36.19 | 820.29 | 36.19 | 849.02 | 36.19 |

| FSSN-HMM | −404.80 | 18.43 | 827.59 | 36.85 | 828.54 | 36.85 | 857.28 | 36.85 | |

| Gaussian-HMM | −408.70 | 18.64 | 831.41 | 37.28 | 831.99 | 37.28 | 854.50 | 37.28 | |

| Parameter | Estimated Value |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 1 × 10−12 | |

| 0.991 | |

| 0.009 | |

| 0.004 | |

| 0.996 | |

| 6879.568 | |

| 7229.954 | |

| 88.677 | |

| 170.374 | |

| 0.348 | |

| 27,871.600 |

| Model | Log-Likelihood | AIC | AICc | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSNBurr-HMM | −3060.60 | 6139.19 | 6139.57 | 6176.72 |

| FSSN-HMM | −3066.02 | 6150.04 | 6150.42 | 6187.56 |

| Gaussian-HMM | −3083.43 | 6180.86 | 6181.10 | 6210.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Unggul, D.B.; Iriawan, N.; Irhamah, I. Parameter Estimation of MSNBurr-Based Hidden Markov Model: A Simulation Study. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111931

Unggul DB, Iriawan N, Irhamah I. Parameter Estimation of MSNBurr-Based Hidden Markov Model: A Simulation Study. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111931

Chicago/Turabian StyleUnggul, Didik Bani, Nur Iriawan, and Irhamah Irhamah. 2025. "Parameter Estimation of MSNBurr-Based Hidden Markov Model: A Simulation Study" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111931

APA StyleUnggul, D. B., Iriawan, N., & Irhamah, I. (2025). Parameter Estimation of MSNBurr-Based Hidden Markov Model: A Simulation Study. Symmetry, 17(11), 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111931