Delannoy Tau-Based Numerical Procedure for the Time-Fractional Cable Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Developing a spectral tau-based algorithm based on employing certain orthogonal polynomials, namely shifted Delannoy polynomials, to treat the TFCE.

- Developing closed formulas for some integrals to implement the tau approach.

- Investigating the error analysis in Delannoy-weighted Sobolev spaces.

- Presenting some illustrative examples to ensure the accuracy and applicability of the proposed numerical method.

- Performing some comparisons with some other methods in the literature.

- The employment of the shifted Delannoy polynomials as orthogonal basis functions within the spectral tau framework for solving the TFCE is new.

- Some operational formulas, such as some integrals, are presented and employed.

2. Preliminaries and Essential Relations

2.1. The Caputo Fractional Derivative

2.2. An Account of Delannoy Polynomials and Their Shifted Versions

2.3. High-Order Derivative Formula for the Shifted Delannoy Polynomials

3. Tau Approach for the TFCE

4. The Error Bound

- An upper bound for is given in Theorem 3.

- An upper bound for is given in Theorem 4.

- An upper bound for is given in Theorem 5.

- Upper bounds for and are given in Theorem 6.

- An upper bound for is given in Theorem 7.

- An upper bound for is given in Theorem 8.

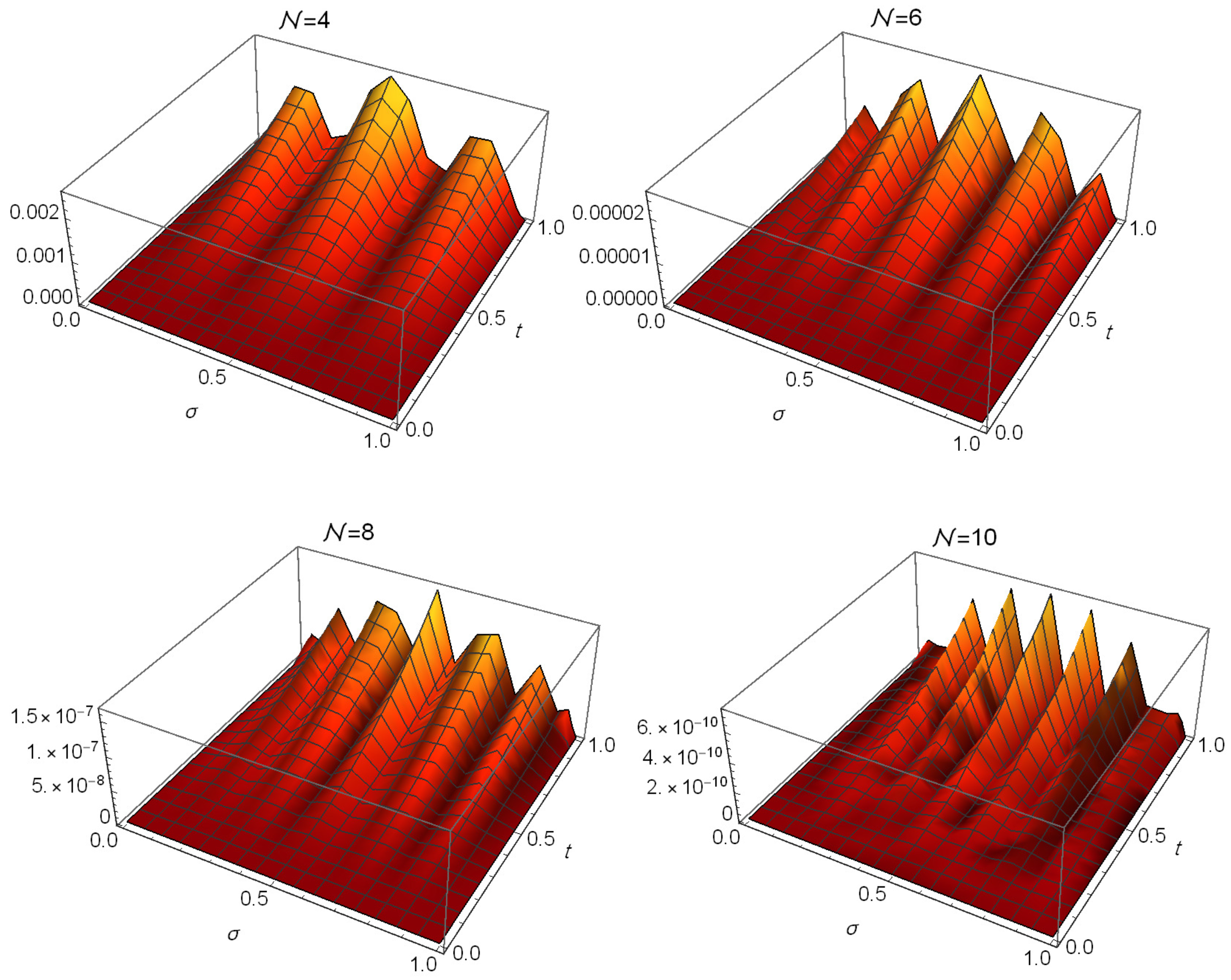

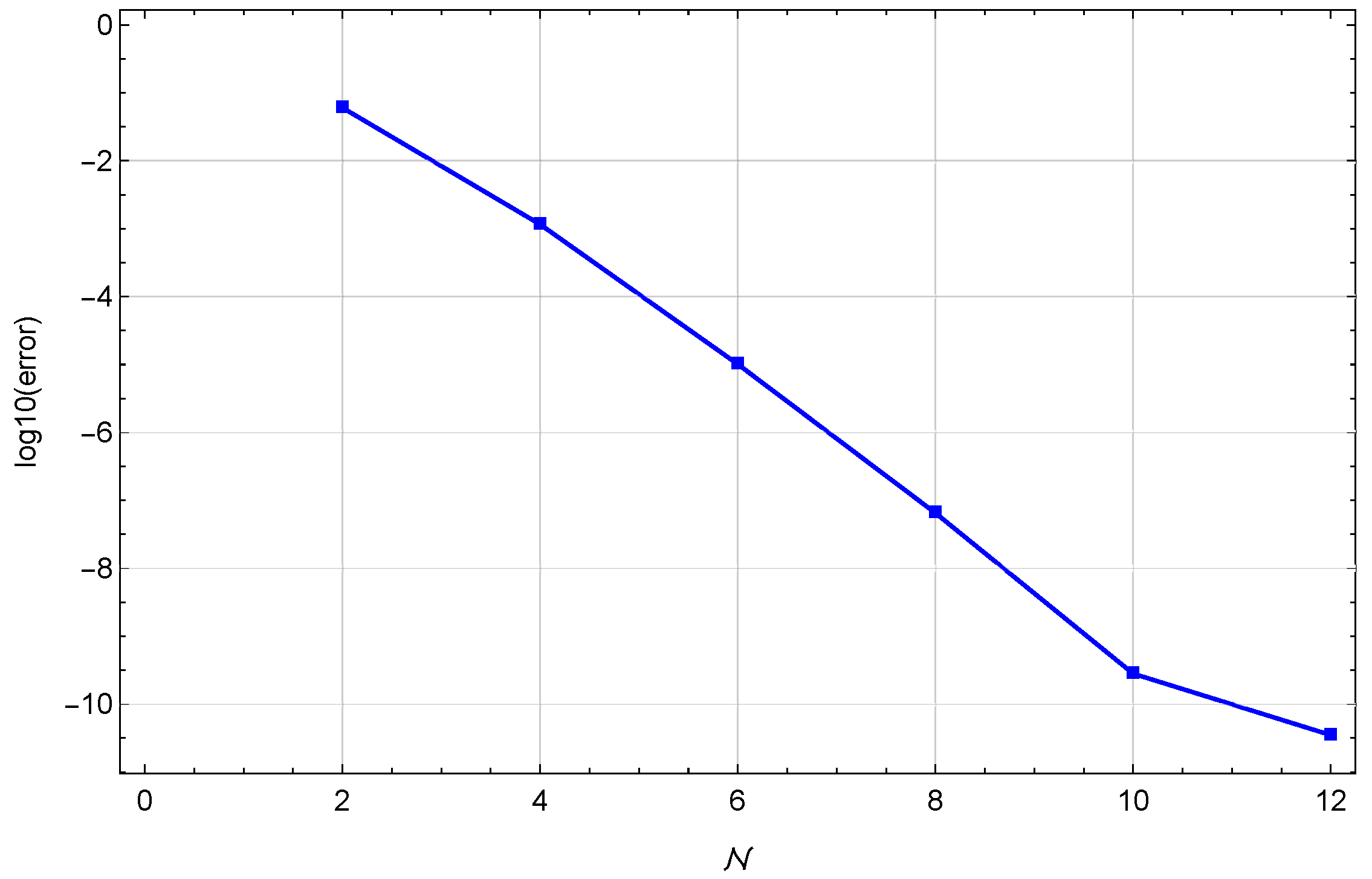

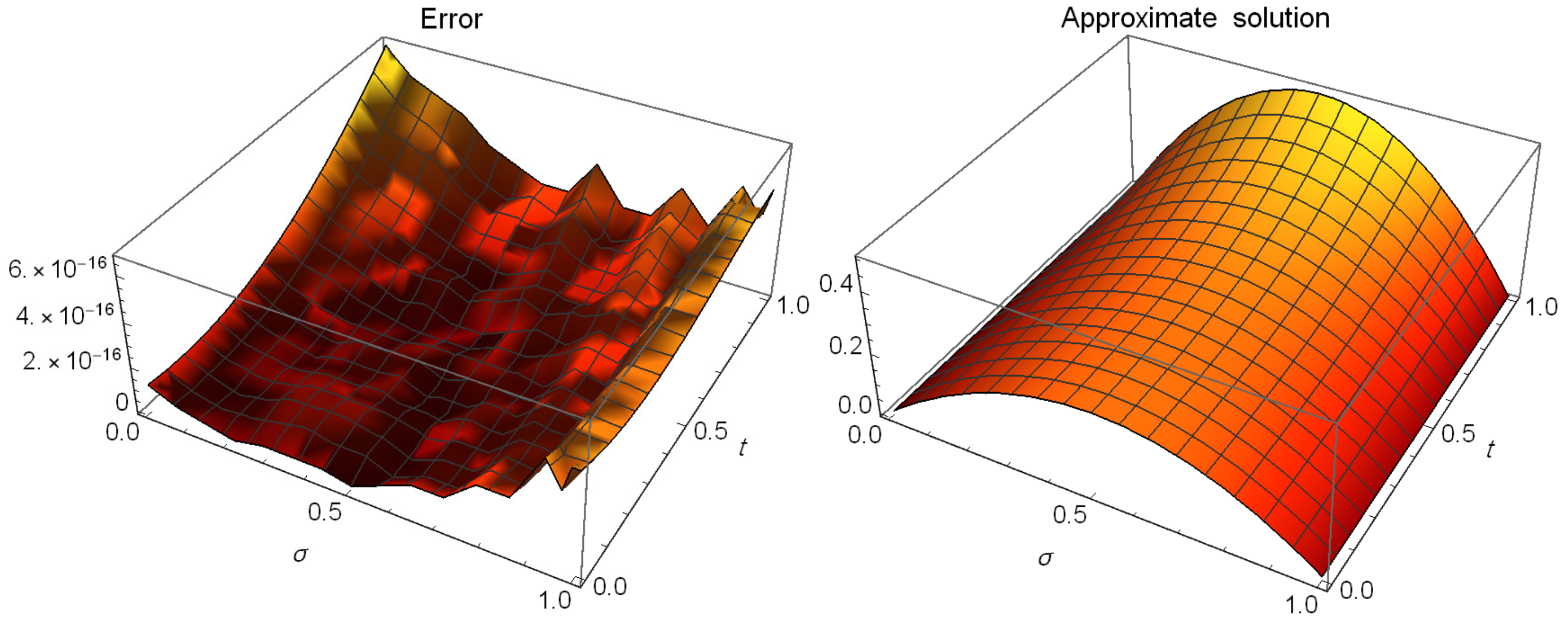

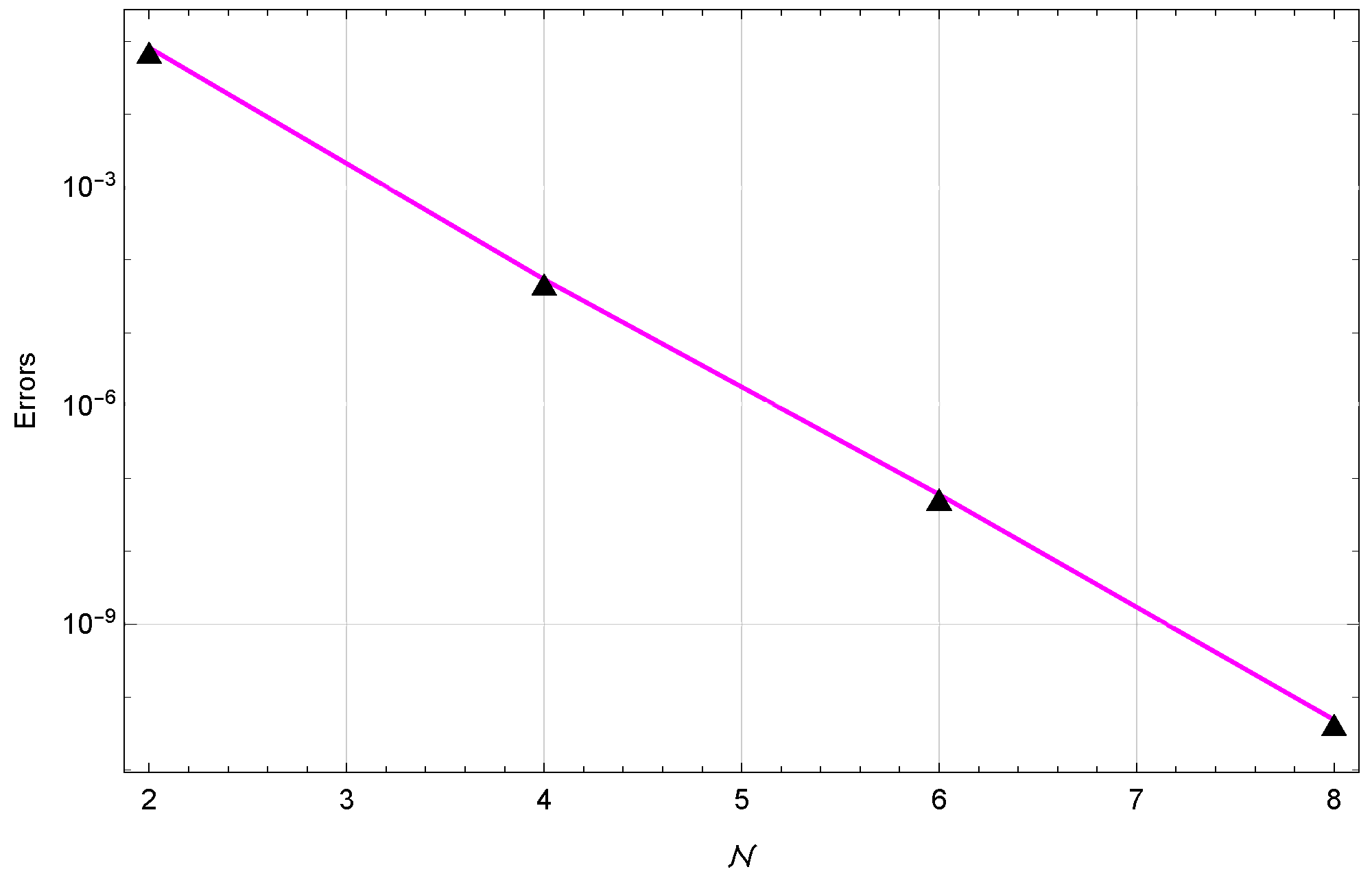

5. Illustrative Examples

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortigueira, M.D. Fractional Calculus in Applied Sciences and Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, V.E. Fractional Dynamics: Applications of Fractional Calculus to Dynamics of Particles, Fields, and Media; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, W.; Pan, B. Modified fractional homotopy method for solving nonlinear optimal control problems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 3453–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Akbar, M.A. A study on the fractional-order COVID-19 SEIQR model and parameter analysis using homotopy perturbation method. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 2024, 12, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamzi, G.; Gouri, A.; Alkahtani, B.S.T.; Dubey, R.S. Analytical solution of generalized Bratu-type fractional differential equations using the homotopy perturbation transform method. Axioms 2024, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J. A spatial sixth-order numerical scheme for solving fractional partial differential equation. Appl. Math. Lett. 2025, 159, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivalingam, S.M.; Kumar, P.; Trinh, H.; Govindaraj, V. A novel L1-Predictor-Corrector method for the numerical solution of the generalized-Caputo type fractional differential equations. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 220, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Singh, S.; Das, P.; Kumar, D. A higher order stable numerical approximation for time-fractional non-linear Kuramoto–Sivashinsky equation based on quintic B-spline. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2024, 47, 11953–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, D.; Baleanu, D. A reliable numerical algorithm based on an operational matrix method for treatment of a fractional order computer virus model. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 3195–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Izadi, M. An accurate approximation technique based on Schröder operational matrices for numerical treatments of time-fractional nonlinear generalized Kawahara equation. Bound. Value Probl. 2025, 2025, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M. Enhanced shifted Jacobi operational matrices of integrals: Spectral algorithm for solving some types of ordinary and fractional differential equations. Bound. Value Probl. 2024, 2024, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasi, H.R.; Derakhshan, M.H.; Ghuraibawi, A.A.; Kumar, P. A novel method based on fractional order Gegenbauer wavelet operational matrix for the solutions of the multi-term time-fractional telegraph equation of distributed order. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 217, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohara, G.; Kumbinarasaiah, S. Fibonacci wavelet collocation method for the numerical approximation of fractional order Brusselator chemical model. J. Math. Chem. 2024, 62, 2651–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, R.; Arora, G.; Singh, B.K.; Emadifar, H. Numerical solution of two-dimensional fractional differential equations using Laplace transform with residual power series method. Nonlinear Eng. 2024, 13, 20220347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhanov, A.A.; Asl, M.S.; Huang, C. Stability analysis of a second-order difference scheme for the time-fractional mixed sub-diffusion and diffusion-wave equation. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2024, 27, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, L. A compact finite difference scheme for solving fractional Black-Scholes option pricing model. J. Inequal. Appl. 2025, 2025, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wen, S.Y.; Fang, Q.; Wang, P. Application of Adomian decomposition method to fractional order partial differential equations. Therm. Sci. 2025, 29, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, C.; Hussaini, M.Y.; Quarteroni, A.; Zang, T.A. Spectral Methods: Fundamentals in Single Domains; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, J.P. Chebyshev and Fourier Spectral Methods, 2nd ed.; Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, L.L. Spectral Methods: Algorithms, Analysis and Applications. In Springer Series in Computational Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Çevik, M.; Savaşaneril, N.B.; Sezer, M. A review of polynomial matrix collocation methods in engineering and scientific applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 3355–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohara, G.; Kumbinarasaiah, S. An innovative Fibonacci wavelet collocation method for the numerical approximation of Emden-Fowler equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 2024, 201, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.; Noreen, A.; Akbar, T.; Arifeen, S.U.; Ghafoor, A.; Khan, Z.A. Numerical solution of seventh order KdV equations via quintic B-splines collocation method. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 114, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, M.; Zaky, M.A.; El-Kady, M.; Abdelhakem, M. Chebyshev polynomial derivative-based spectral tau approach for solving high-order differential equations. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 43, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhameed, W.M.; Abu Sunayh, A.F.; Alharbi, M.H.; Atta, A.G. Spectral tau technique via Lucas polynomials for the time-fractional diffusion equation. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 34567–34587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhameed, W.M.; Youssri, Y.H.; Atta, A.G. Adopted spectral tau approach for the time-fractional diffusion equation via seventh-kind Chebyshev polynomials. Bound. Value Probl. 2024, 2024, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhameed, W.M.; Ahmed, H.M. Spectral solutions for the time-fractional heat differential equation through a novel unified sequence of Chebyshev polynomials. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 2137–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Aeri, S.; Bala, A.; Kumar, R.; Baleanu, D. Solving system of fractional differential equations via Vieta-Lucas operational matrix method. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2024, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elaziz El-Sayed, A.; Boulaaras, S.; Sweilam, N.H. Numerical solution of the fractional-order logistic equation via the first-kind Dickson polynomials and spectral tau method. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 8004–8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, N.; Sejnowski, T. An electro-diffusion model for computing membrane potentials and ionic concentrations in branching dendrites, spines and axons. Biol. Cybern. 1989, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, M.J. Anomalous subdiffusion in fluorescence photobleaching recovery: A Monte Carlo study. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 2226–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, F.M. On numerical simulations of variable-order fractional cable equation arising in neuronal dynamics. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.V.D.; Prakasha, D.G.; Veeresha, P.; Kapoor, M. A homotopy-based computational scheme for two-dimensional fractional cable equation. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2024, 38, 2450292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosari, S.; Xu, P.; Shafi, J.; Derakhshan, M.H. An efficient hybrid numerical approach for solving two-dimensional fractional cable model involving time-fractional operator of distributed order with error analysis. Numer. Algorithms 2024, 99, 1269–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweilam, N.H.; Ahmed, S.M.; Al-Mekhlafi, S.M. Two-dimensional distributed order Cable equation with non-singular kernel: A nonstandard implicit compact finite difference approach. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Mech. 2024, 23, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikan, O.; Golbabai, A.; Machado, J.A.T.; Nikazad, T. Numerical approximation of the time fractional Cable model arising in neuronal dynamics. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Shokri, A. A pseudo-spectral approach to solving the fractional Cable equation using Lagrange polynomials. Anal. Numer. Solut. Nonlinear Equ. 2025, 9, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, A.K.; Balyan, L.K.; Panda, M.K.; Shrivastava, P.; Singh, H. Pseudospectral analysis and approximation of two-dimensional fractional Cable equation. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022, 45, 8613–8630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, A.; Avazzadeh, Z. Barycentric–Legendre interpolation method for solving two-dimensional fractional Cable equation in neuronal dynamics. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2022, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biranvand, N.; Ebrahimijahan, A. Utilizing differential quadrature-based RBF partition of unity collocation method to simulate distributed-order time fractional Cable equation. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 43, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 198. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, S.G.; Atta, A.G.; Youssri, Y.H. A spectral Delannoy polynomial-based computational framework for fractional differential problems in complex systems. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Askey, R.; Roy, R. Special Functions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Numerical simulation of time fractional cable equations and convergence analysis. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2018, 34, 1556–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.L.; Xie, Z. Sharp error bounds for Jacobi expansions and Gegenbauer–Gauss quadrature of analytic functions. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2013, 51, 1443–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, H. A time–space spectral tau method for the time fractional cable equation and its inverse problem. Appl. Numer. Math. 2018, 130, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghi, N.; Saadatmandi, A. Numerical solution of time fractional cable equation via the sinc-Bernoulli collocation method. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2021, 7, 1916–1924. [Google Scholar]

| Algorithm in [46] | Algorithm in [47] | Proposed Algorithm () | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 |

| Algorithm in [46] at | Proposed algorithm () | Algorithm in [46] at | Proposed algorithm () |

| Algorithm in [47] | Proposed algorithm () | Algorithm in [47] | Proposed algorithm () |

| CPU Time | CPU Time | CPU Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | ||||||

| 0.2 | ||||||

| 0.3 | ||||||

| 0.4 | ||||||

| 0.5 | 284.53 | 284.53 | 284.53 | |||

| 0.6 | ||||||

| 0.7 | ||||||

| 0.8 | ||||||

| 0.9 |

| Error | Error | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm in [47] | Proposed Algorithm () | Algorithm in [47] | Proposed Algorithm () | ||

| 0.5 | 0.5 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.8 | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.9 | ||||

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU time | 3.157 | 8.016 | 23.124 | 61.437 | 161.172 |

| CPU time | 2.797 | 7.704 | 20.97 | 54.328 | 142.454 |

| 0.1 | |||

| 0.2 | |||

| 0.3 | |||

| 0.4 | |||

| 0.5 | |||

| 0.6 | |||

| 0.7 | |||

| 0.8 | |||

| 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atta, A.G.; Abdelkawy, M.A.; Alsafri, N.M.A.; Abd-Elhameed, W.M. Delannoy Tau-Based Numerical Procedure for the Time-Fractional Cable Model. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111916

Atta AG, Abdelkawy MA, Alsafri NMA, Abd-Elhameed WM. Delannoy Tau-Based Numerical Procedure for the Time-Fractional Cable Model. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111916

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtta, Ahmed Gamal, Mohamed A. Abdelkawy, Naher Mohammed A. Alsafri, and Waleed Mohamed Abd-Elhameed. 2025. "Delannoy Tau-Based Numerical Procedure for the Time-Fractional Cable Model" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111916

APA StyleAtta, A. G., Abdelkawy, M. A., Alsafri, N. M. A., & Abd-Elhameed, W. M. (2025). Delannoy Tau-Based Numerical Procedure for the Time-Fractional Cable Model. Symmetry, 17(11), 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111916