Deformation Control Technology for Surrounding Rock in Soft Rock Roadways of Deep Kilometer-Scale Mining Wells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Simulation Scheme for Surrounding Rock Deformation in Deep Soft Rock Mining Roadways

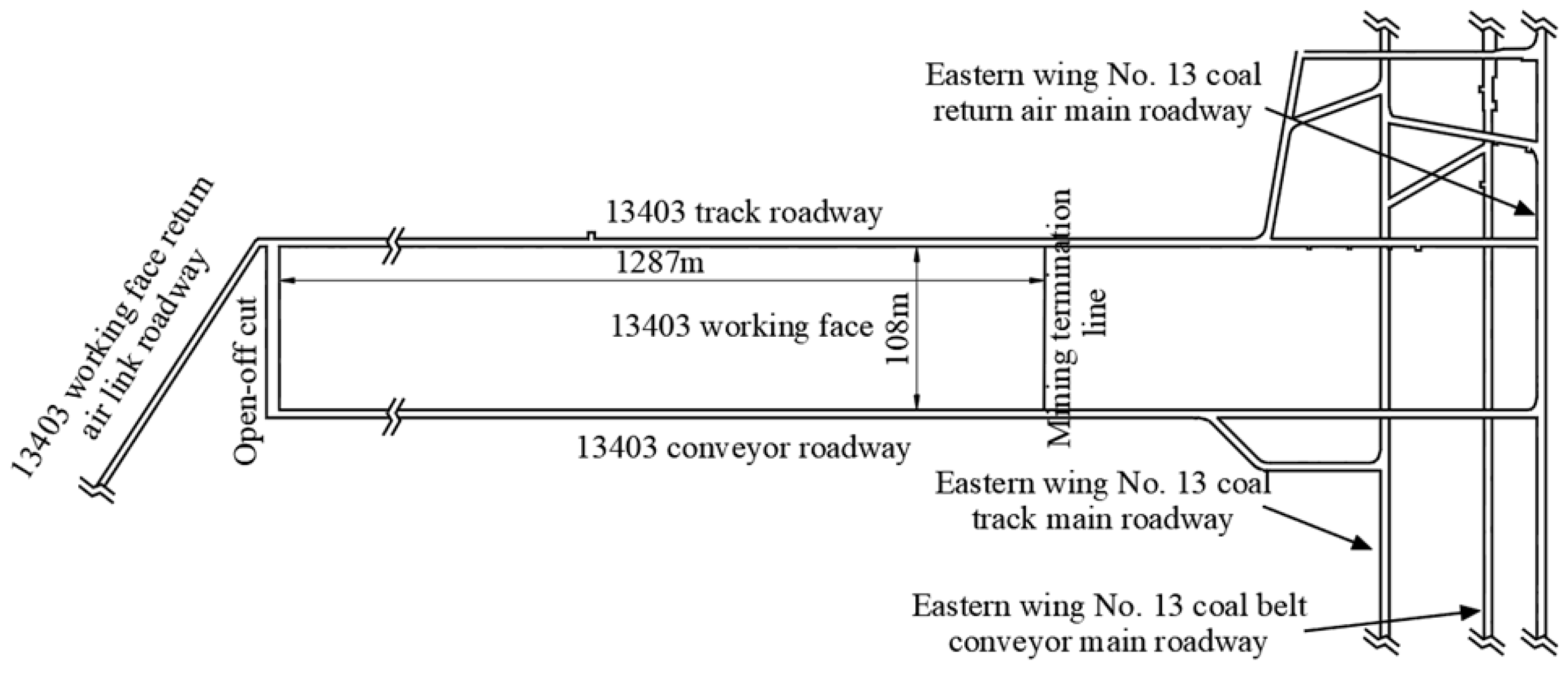

2.1. Engineering Background

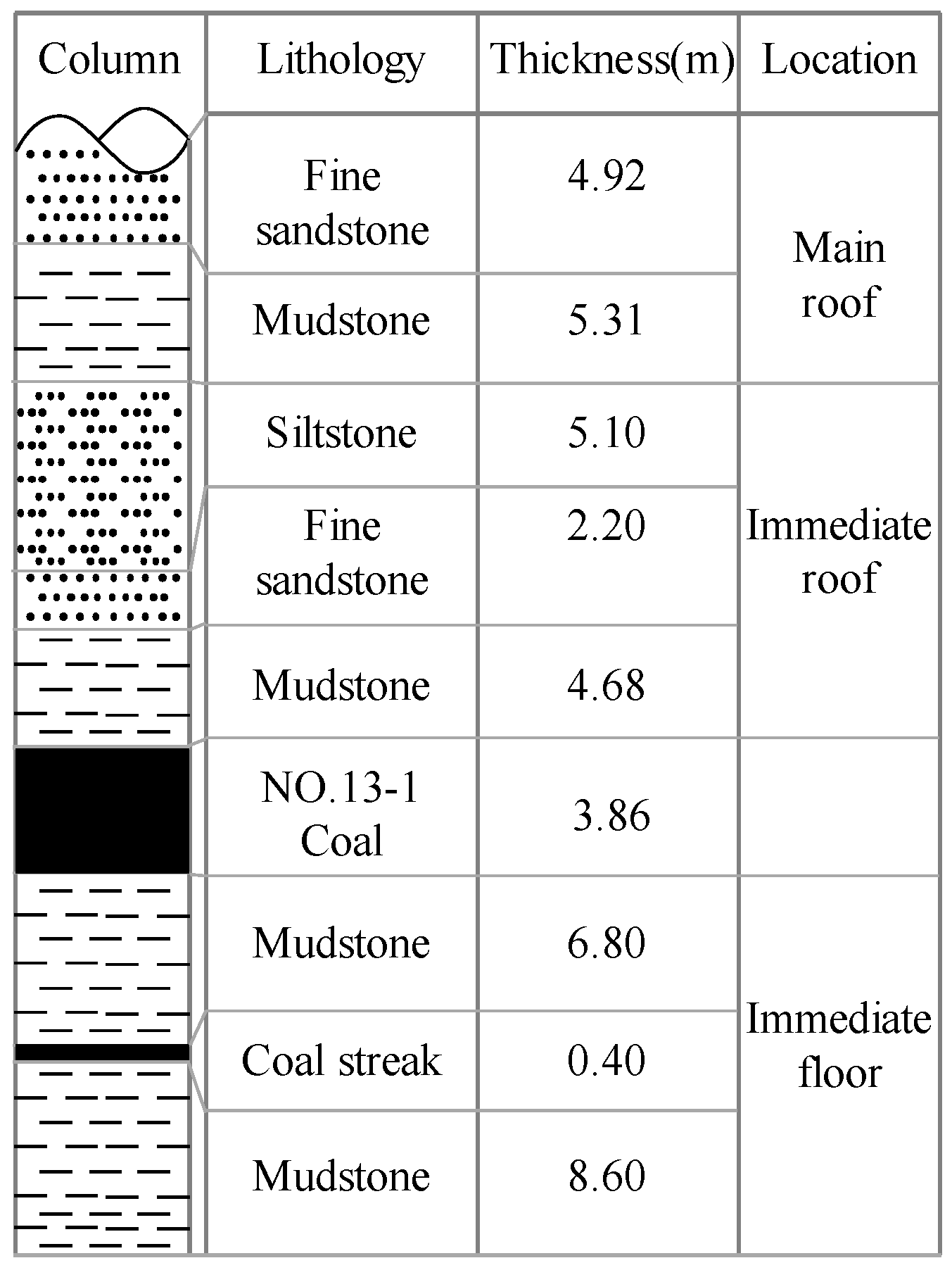

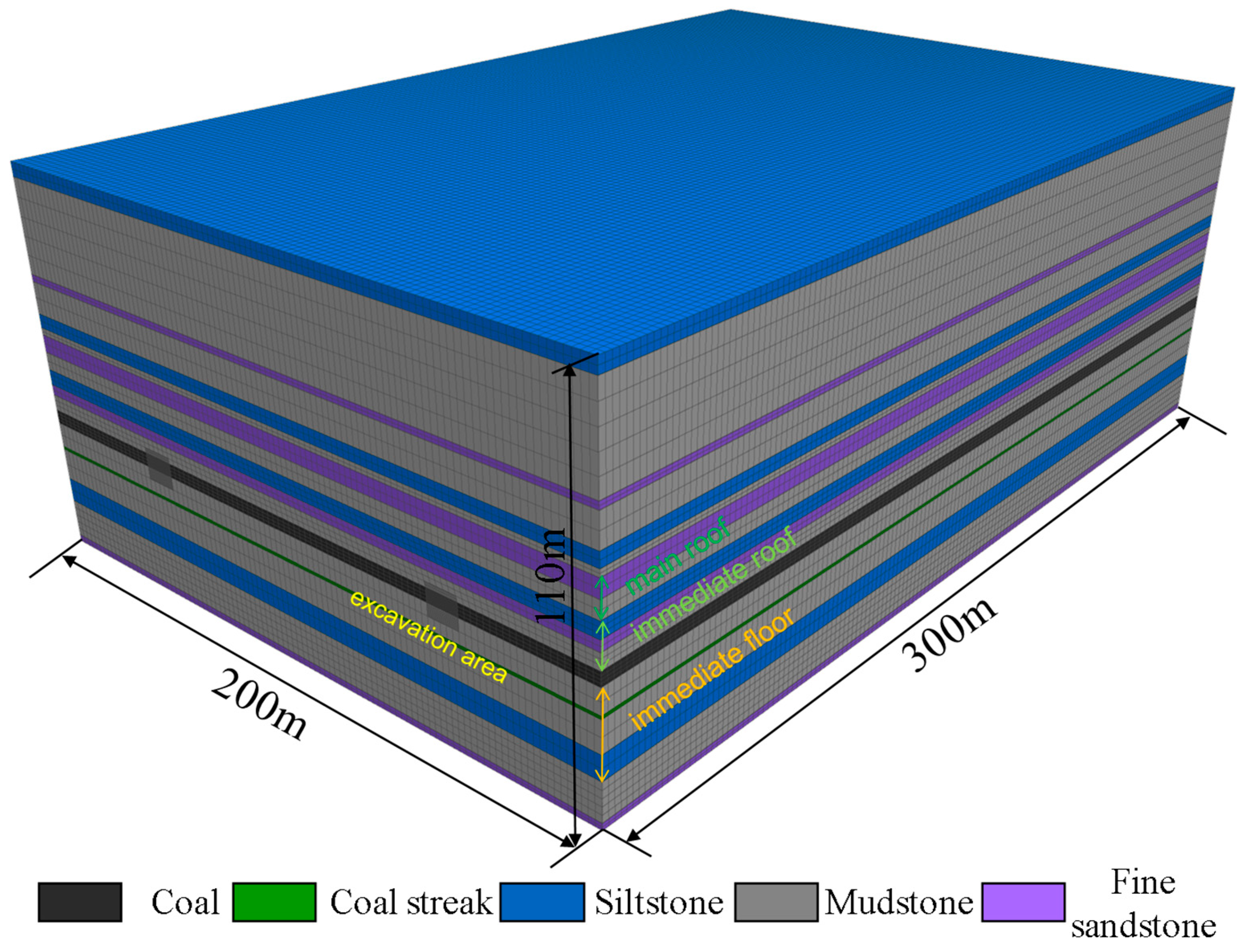

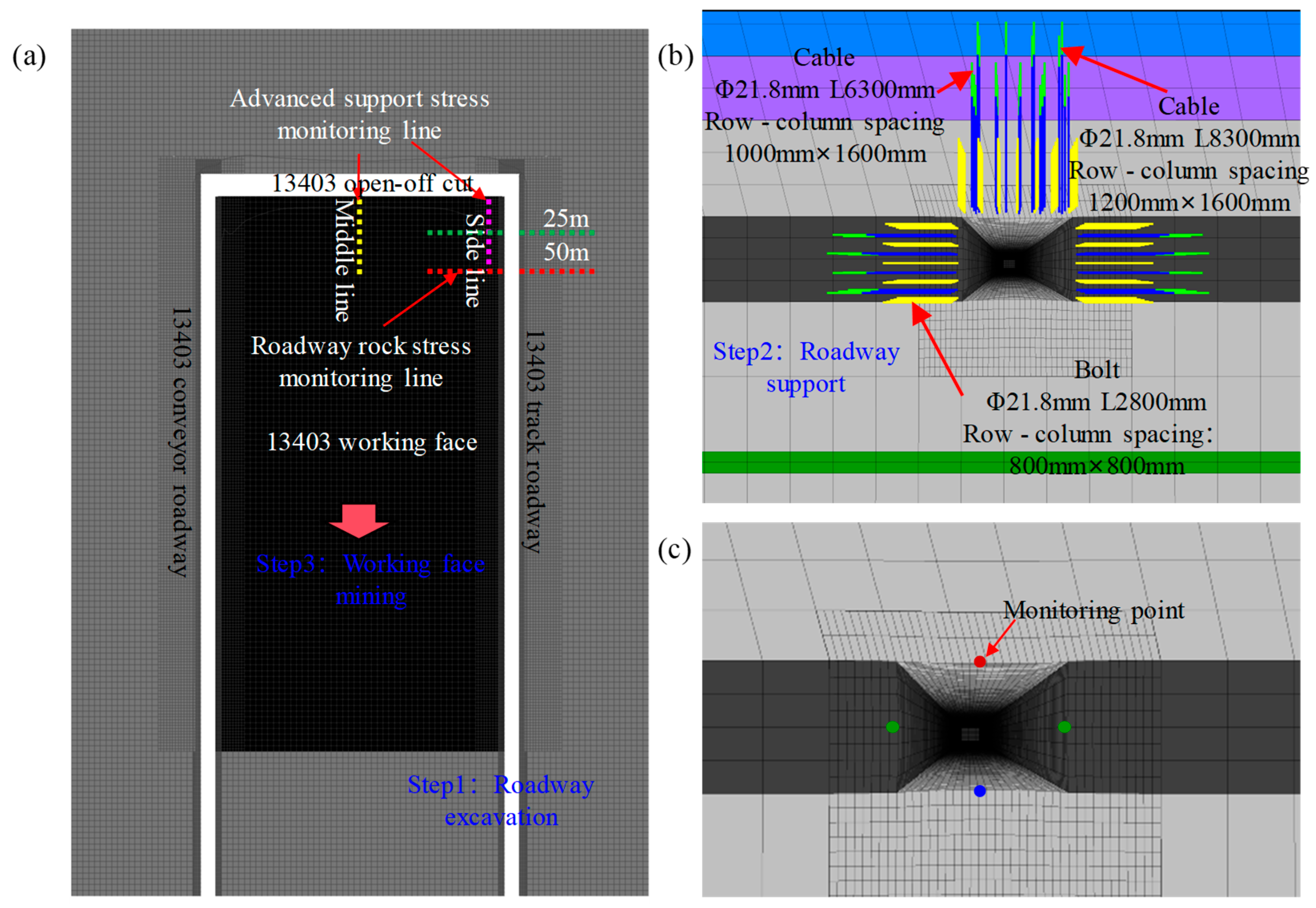

2.2. Model Construction

2.3. Simulation Scheme and Process

2.4. Monitoring Scheme

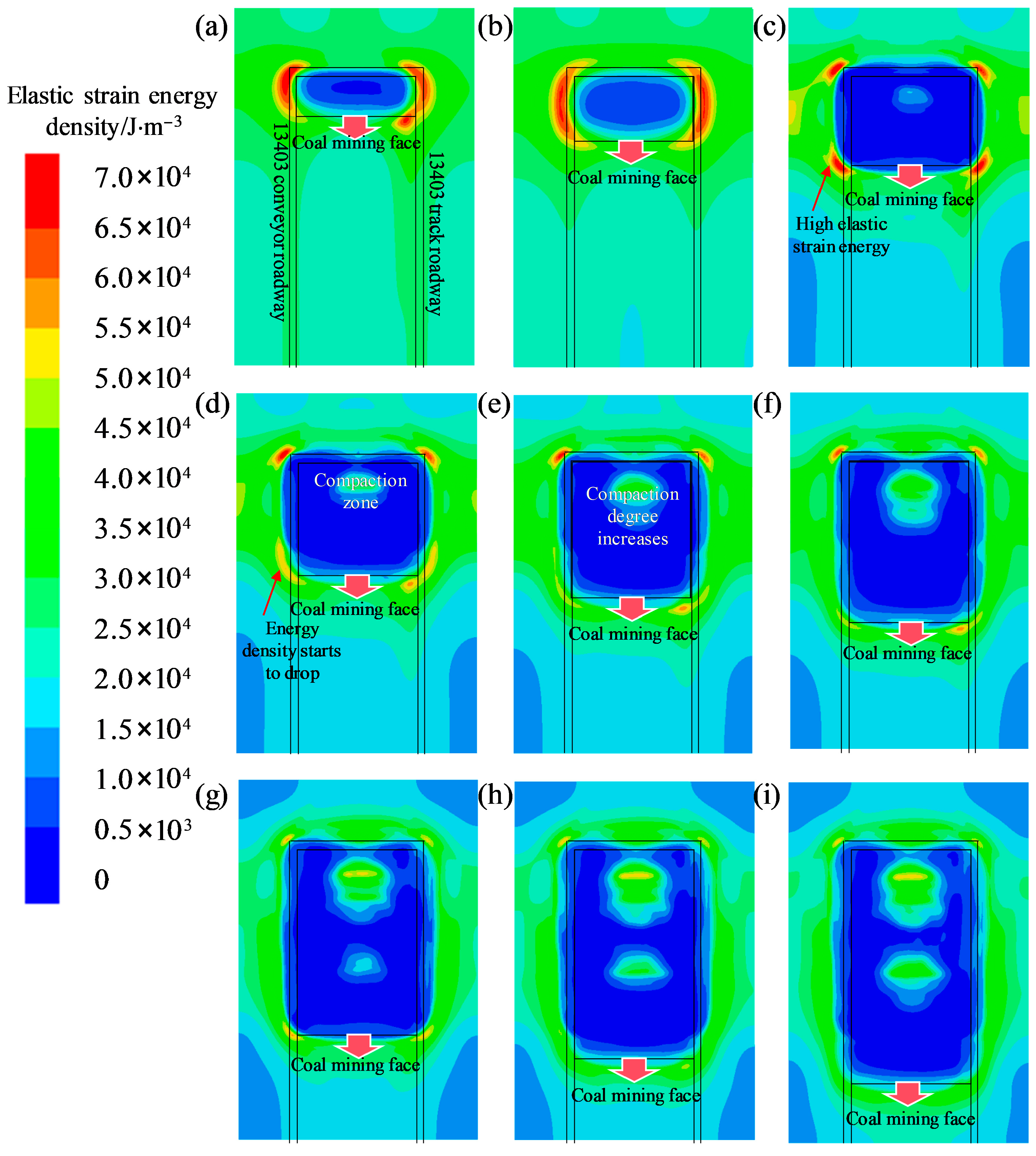

3. Evolution Law of Elastic Strain Energy in the Roof and Deformation Control of Kilometer-Deep Soft Rock Roadway

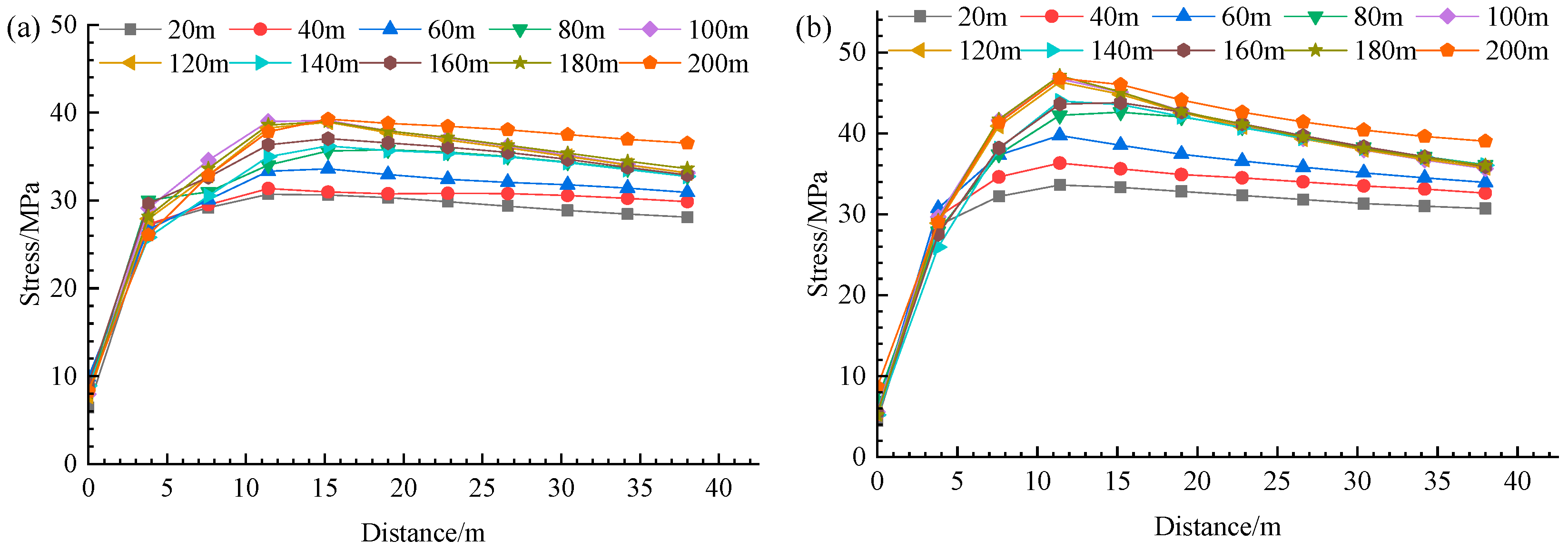

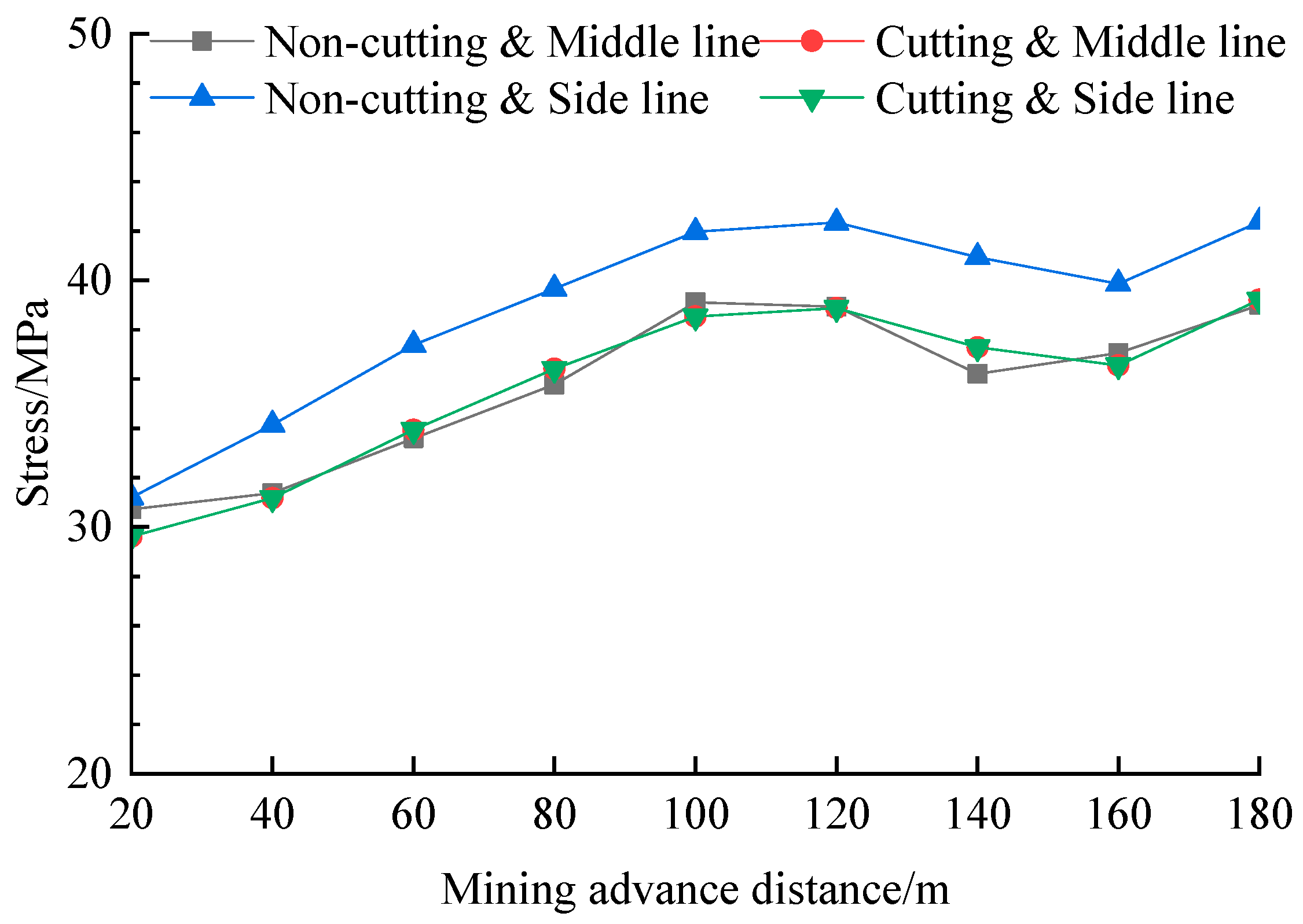

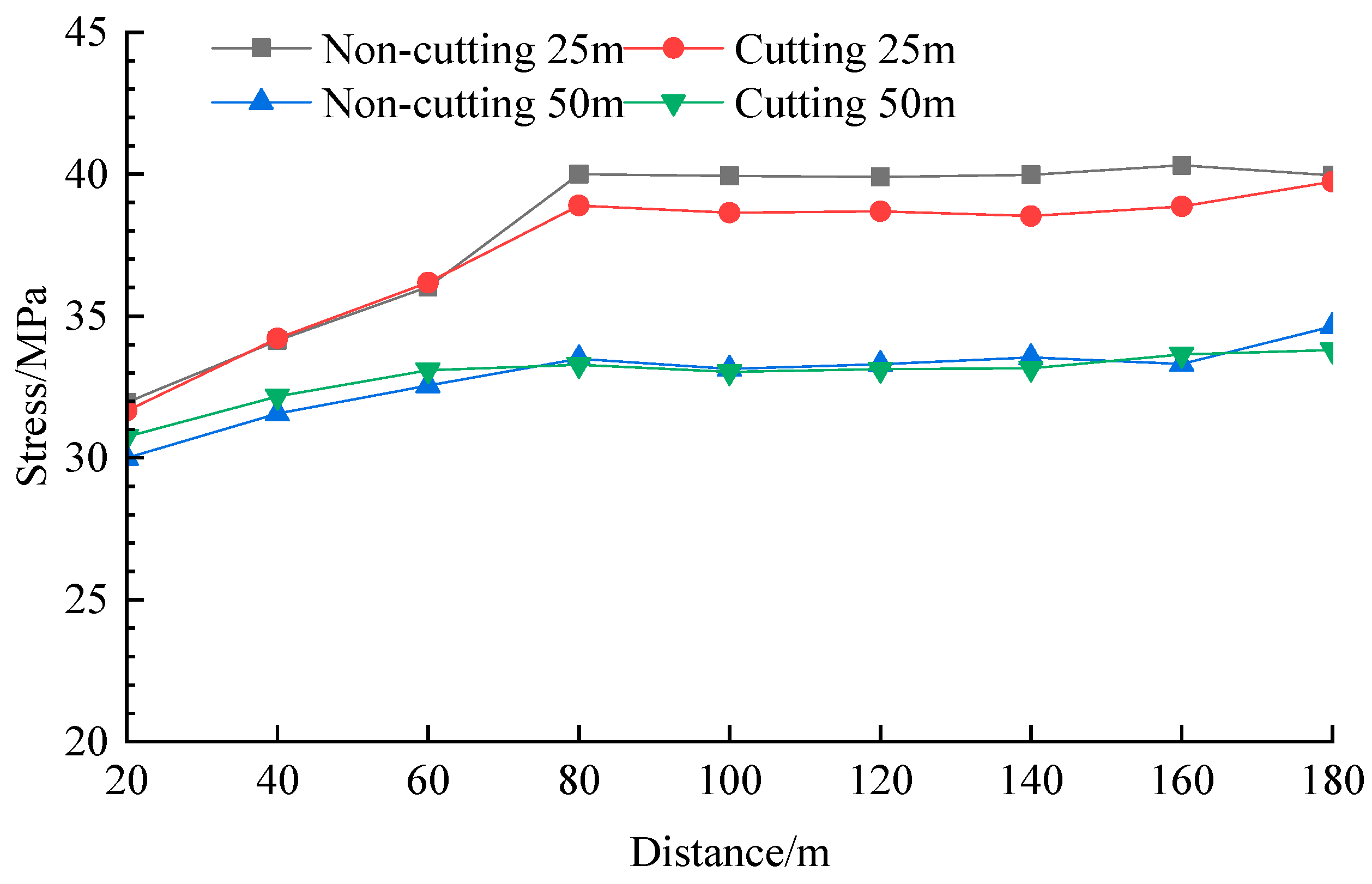

3.1. Evolution Law of Advance Abutment Stress in the Working Face

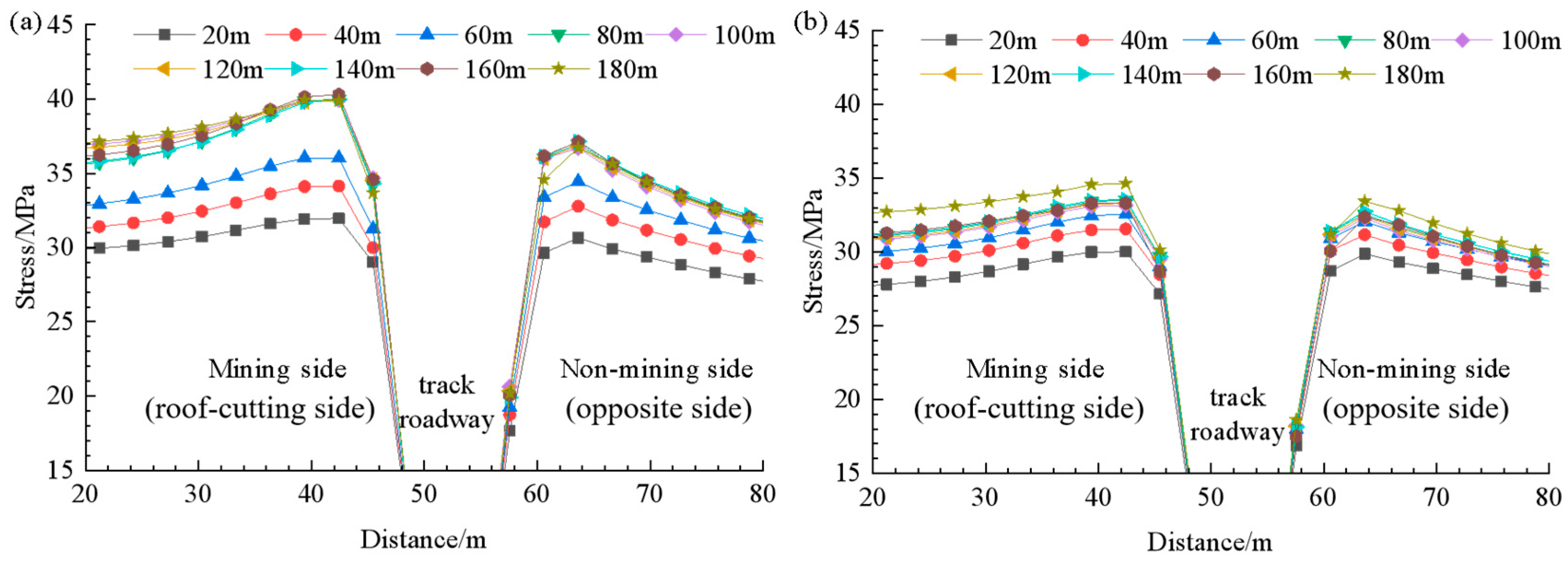

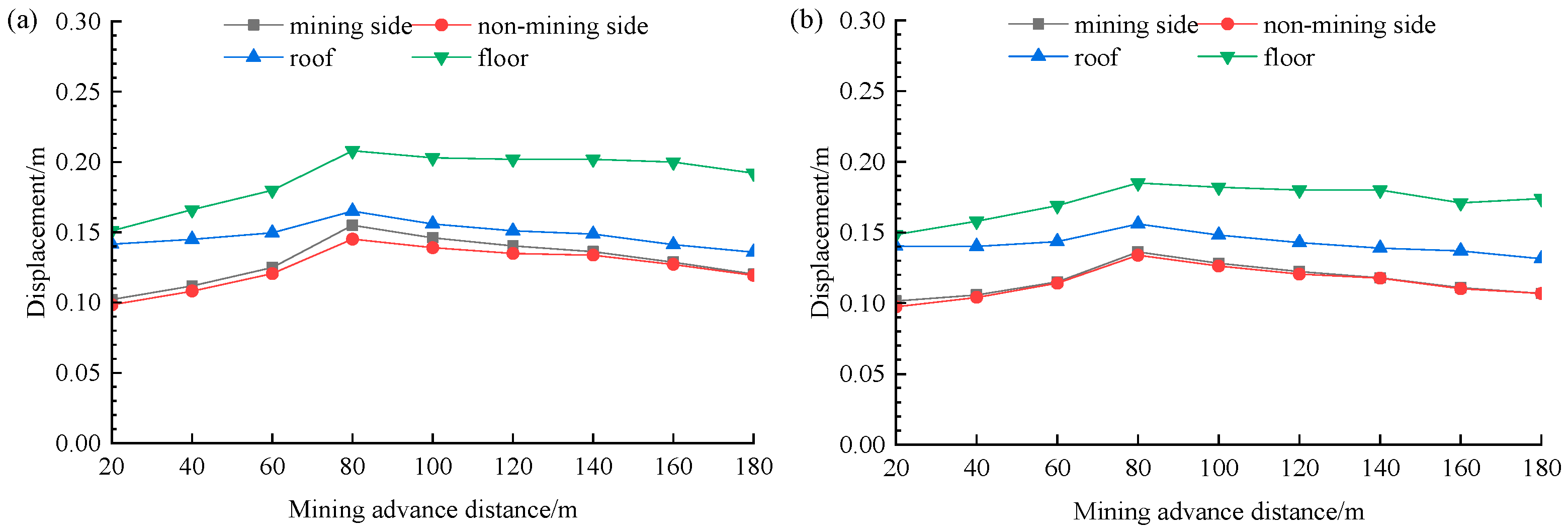

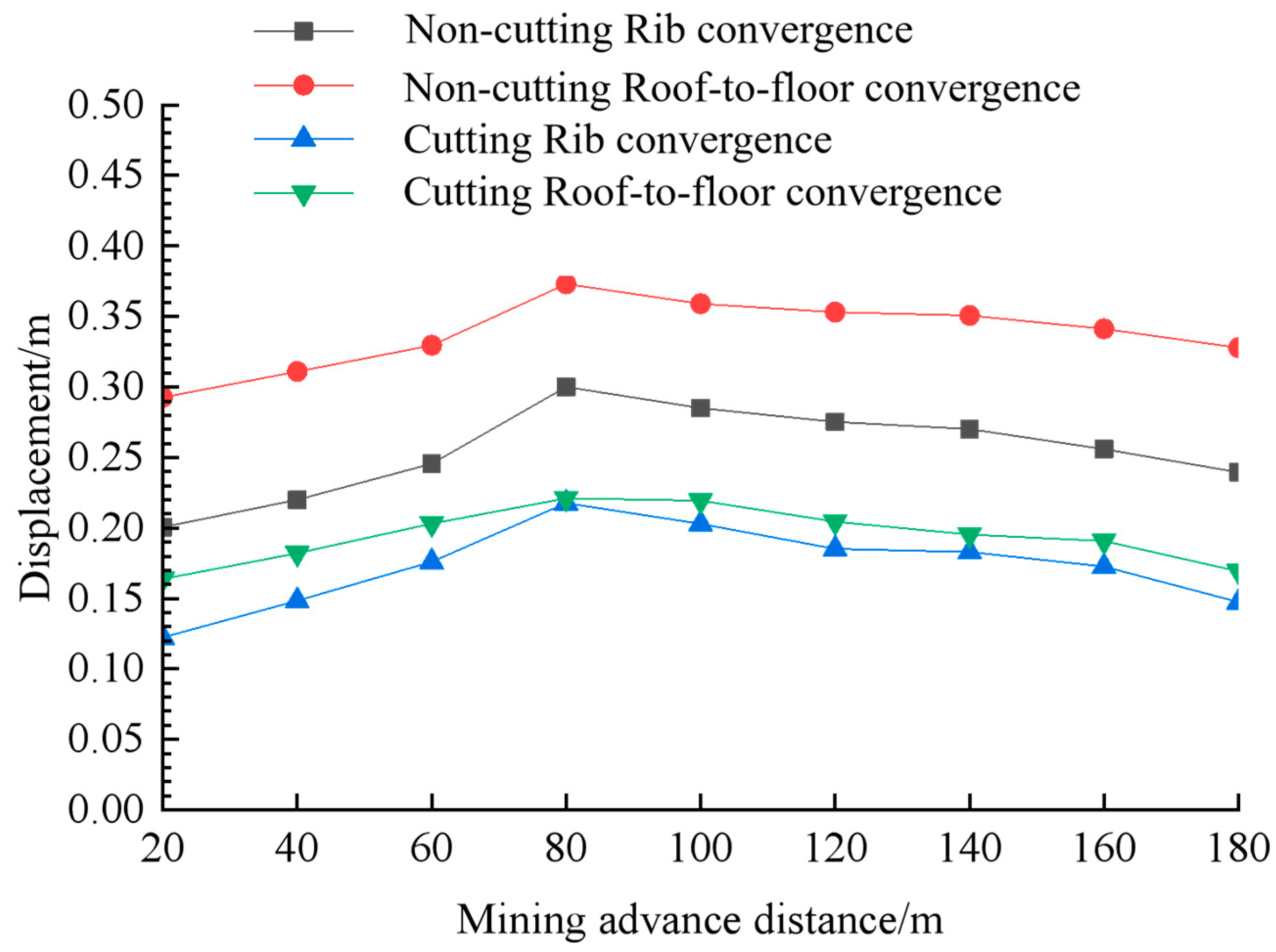

3.2. Evolution Law of Support Stress and Deformation in Surrounding Rock of Working Face Roadway

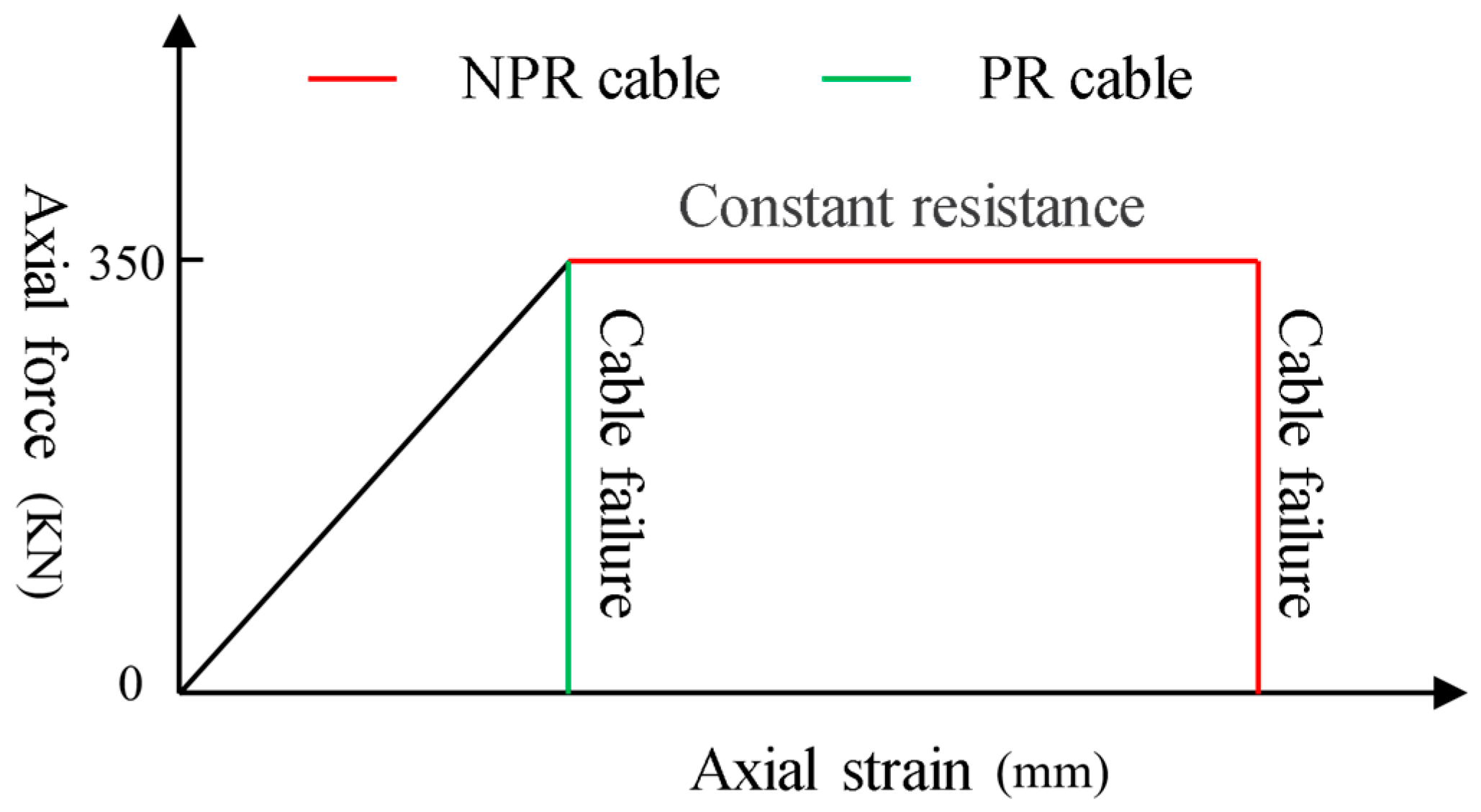

4. Surrounding Rock Deformation Control Technology for Deep Soft Rock Mining Roadways

5. Engineering Application Analysis

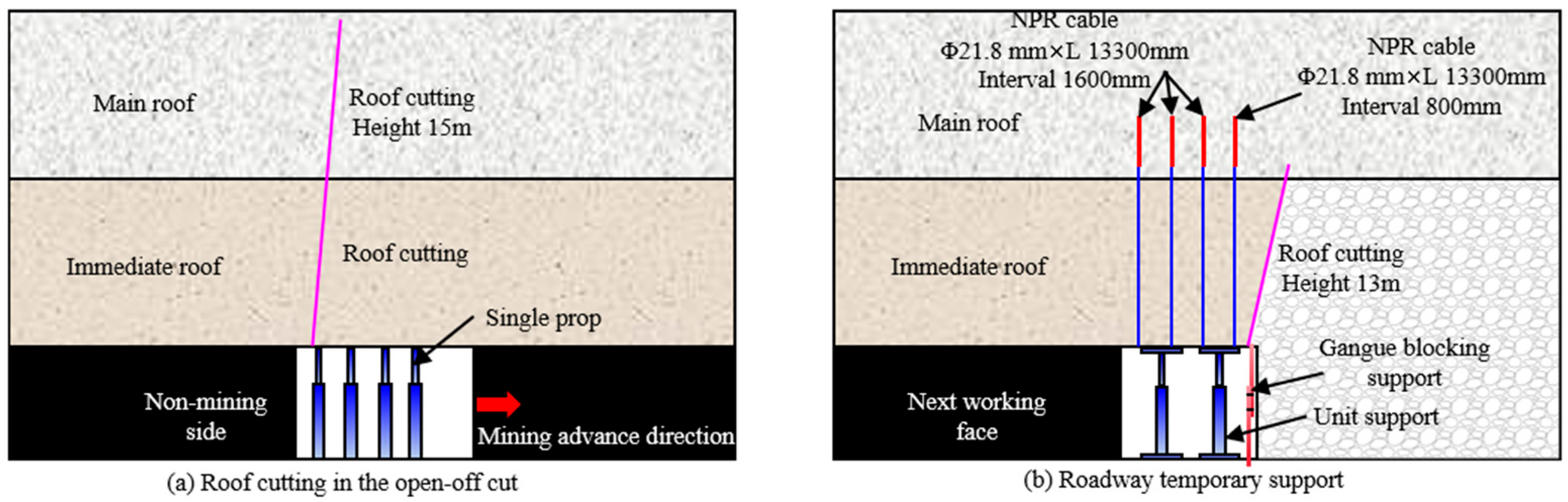

5.1. Surrounding Rock Control Technical Scheme

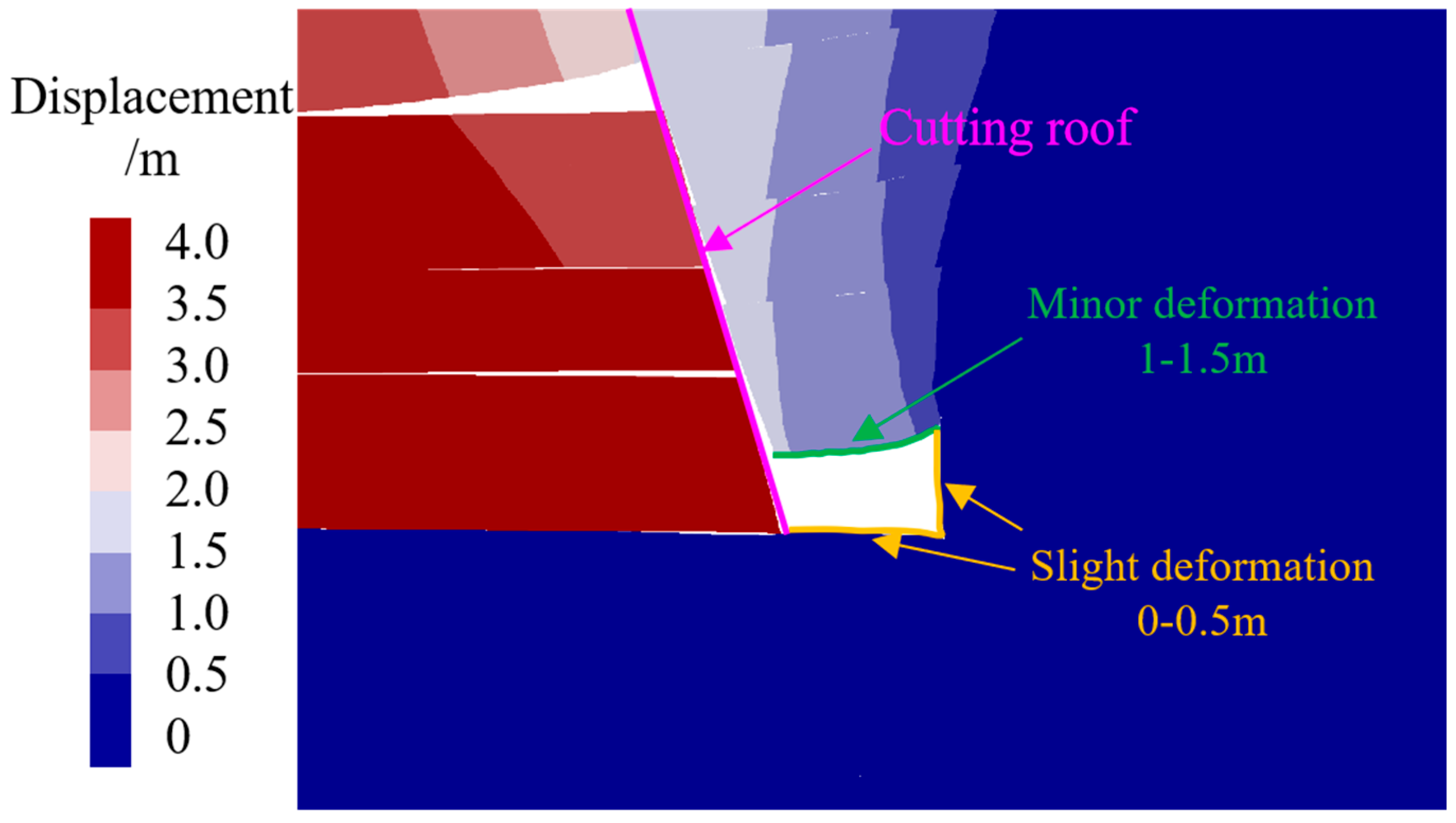

5.2. Numerical Simulation Analysis of Surrounding Rock Control Effect

5.3. Field Implementation at Face 13403: Configuration and Observed Outcomes

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, H.-P. Research review of the state key research development program of China: Deep rock mechanics and mining theory. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 1283–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L. Strategic thinking of simultaneous exploitation of coal and gas in deep mining. J. China Coal Soc. 2016, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.-C. Conception system and evaluation indexes for deep engineering. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 2854–2858. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.-C.; Hu, J.; Cheng, T.; Deng, F.; Tao, Z.-G.; Li, H.-R.; Peng, D. Dynamic properties of micro-NPR material and its controlling effect on surrounding rock mass with impact disturbances. Undergr. Space 2024, 15, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-P.; Tan, Z.-S.; Zhang, B.-J.; Wang, F.-X. Stress-Release Technology and Engineering Application of Advanced Center Drifts in a Super-Deep Soft-Rock Tunnel: A Case Study of the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 7103–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Maurya, S.; Tiwari, G. Reliability analysis of deep tunnels in spatially varying brittle rocks using interval and random field modelling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 181, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, F.; Zheng, J.; Wang, F.-N.; Tao, Z.-G. Study on the Support Strategy of NPR Cable Truss Structure in Large Deformation Soft Rock Tunnel Across Multistage Faults. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 11261–11281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huo, S.-S.; He, M.-C.; Tao, Z.-G. Compensation mechanics application of NPR anchor cable to large deformation tunnel in soft rock. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Luo, Z.-Y.; Wu, C.-Z.; Lu, H.; Zhu, C. Integrated early warning and reinforcement support system for soft rock tunnels: A novel approach utilizing catastrophe theory and energy transfer laws. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 150, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-P.; Xu, N.-W.; Xiao, P.-W.; Sun, Z.-Q.; Li, H.-L.; Liu, J.; Li, B. Characterizing large deformation of soft rock tunnel using microseismic monitoring and numerical simulation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, Y. Deep Soft Rock Tunnel Perimeter Rock Control Technology and Research. Appl. Sci. 2024, 15, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.-X.; Li, Y.-M.; Liu, G.; Meng, X.-R. Mechanism analysis and control technology of surrounding rock failure in deep soft rock roadway. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 115, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yao, Q.-L.; Xu, Q.; Yu, L.-Q.; Qu, Q.-D. Large deformation characteristics of surrounding rock and support technology of shallow-buried soft rock roadway: A case study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-P.; Yang, J.-W.; Jiang, P.-F.; Gao, F.-Q.; Li, W.-Z.; Li, J.-F.; Chen, H.-Y. Theory, technology and application of grouted bolting in soft rock roadways of deep coal mines. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 1463–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.-H.; Chang, J.-C.; Shi, W.-B.; Wang, T.; Qiao, L.-Q.; Guo, Y.-J.; Wang, H.-D. Creep deformation characteristics and control technology in deep mine soft rock roadway. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Jiang, Y.-J.; Sun, X.-M.; Luan, H.-J.; Zhang, H. Nonlinear large deformation mechanism and stability control of deep soft rock roadway: A case study in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.-W.; Zhou, H.; Sun, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, C.-Y.; Wang, J. Failure mechanism and safety control technology of a composite strata roadway in deep and soft rock masses: A case study. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 2427–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, N.-K.; Bai, J.-B.; Yoo, C.-S. Failure mechanism and control technology of deep soft-rock roadways: Numerical simulation and field study. Undergr. Space 2023, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Ying, X. Pressure relief for drilling (trenching) and support technology in deep soft rock tunnels. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1501420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.-D.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-S.; Chen, X.-Y. Study on surrounding rock-bearing structure and associated control mechanism of deep soft rock roadway under dynamic pressure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.-J.; Zheng, X.-G.; Du, J.-P.; Xiao, T. Coupling instability mechanism and joint control technology of soft-rock roadway with a buried depth of 1336 m. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 2233–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.-P.; Gao, F.; Ju, Y. Research and development of rock mechanics in deep ground engineering. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 34, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Yang, J.; Song, H.-X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.-X.; Wei, X.-J. Study on the method of pressure relief and energy absorption for protecting roadway under thick and hard roof. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 7177–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Q.-W.; Tu, M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Q.-C. Analysis of energy accumulation and dispersion evolution of a thick hard roof and dynamic load response of the hydraulic support in a large space stope. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 884361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.-W.; Xue, F.; Bai, G.-C.; Li, T.-C.; Wang, B.-X.; Zhao, J.-W. An exploration of improving the stability of mining roadways constructed in soft rock by roof cutting and stress transfer: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.-B.; Kong, L.-H.; Han, L.-U.; Li, Y.; Nie, J.-W.; Li, H.; Gao, J. Stability control technology for deep soft and broken composite roof in coal roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 2017, 42, 2554–2564. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.-C.; Guo, A.-P.; Meng, Z.-G.; Pan, Y.-F.; Tao, Z.-G. Impact and explosion resistance of NPR anchor cable: Field test and numerical simulation. Undergr. Space 2023, 10, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, C.-Z.; He, M.-C.; Gong, W. Mechanical behavior of soft rock roadway reinforced with NPR cables: A physical model test and case study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 138, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-C.; Yin, M.-S.; Zhou, G.-L.; Tao, G.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Yan, X.-Y.; Li, Z.-G.; Lvu, K. Evolution law of stress and energy field accumulation during the fracture of plate structure in Thick and hard rock strata. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2024, 53, 647–663. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Li, A.-W. Analytic solutions of deflection, bending moment and energy change of tight roof of advanced working surface during initial fracturing. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2012, 31, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-W.; Jiang, Y.-D.; Gao, R.-J.; Liu, S. Evolution of energy field instability of island longwall panel during coal bump. Rock Soil Mech. 2013, 34, 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.-Y.; He, C.; Walton, G.; Chen, Z.-Q. A combined support system associated with the segmental lining in a jointed rock mass: The case of the inclined shaft tunnel at the Bulianta coal mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 2653–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-B.; Wang, Y.-J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; He, M.-C. Meso-and macroeffects of roof split blasting on the stability of gateroad surroundings in an innovative nonpillar mining method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 90, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ma, L.; Ngo, I. Mechanism and control of deformation in gob-side entry with thick and hard roof strata. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2023, 123, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; He, M.-C.; Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Ma, Z.-M.; Ming, C.; Wang, R.; Feng, Z.-C.; Zhang, W.-J. Study on deformation mechanism and roof pre-splitting control technology of gob-side entry in thick hard main roof full-mechanized longwall caving panel. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 3206–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Wang, J.; He, M.-C.; Ma, Z.-M.; Tian, X.-C.; Liu, P. A novel non-pillar coal mining technology in longwall top coal caving: A case study. Energy Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1822–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Yang, J.; He, M.-C.; Tian, X.-C.; Liu, J.-N.; Xue, H.-J.; Huang, R.-F. Test of a liquid directional roof-cutting technology for pressure-relief entry retaining mining. J. Geophys. Eng. 2019, 16, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Du, M.-Q.; Xi, C.-H.; Yuan, H.-P.; He, W.-S. Mechanics principle and implementation technology of surrounding rock pressure release in gob-side entry retaining by roof cutting. Processes 2022, 10, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Jiang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Hou, S.-L.; He, M.-C.; Ma, L. Experiment research on the control method of automatically retained entry by roof cutting pressure relief within thick hard main roof longwall top coal caving panel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 168, 109085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, P.; He, M.-C.; Tian, H.-Z.; Gong, W.-L. Mechanical behaviour of a deep soft rock large deformation roadway supported by NPR bolts: A case study. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 8851–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stratum | Density/(kg m3) | Bulk/(GPa) | Shear/(GPa) | Friction/(°) | Cohesion/(MPa) | Tension/(MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mudstone | 2460 | 6.08 | 3.47 | 30 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Coal | 1350 | 4.91 | 2.01 | 30 | 1.25 | 0.9 |

| Siltstone | 2460 | 10.83 | 8.13 | 38 | 2.75 | 2.6 |

| Fine sandstone | 2870 | 20.01 | 13.52 | 42 | 3.2 | 2.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; Li, H.; Ma, L.; Guan, W.; Wang, H.; Feng, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, R. Deformation Control Technology for Surrounding Rock in Soft Rock Roadways of Deep Kilometer-Scale Mining Wells. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111911

Jiang L, Li H, Ma L, Guan W, Wang H, Feng H, Zhang B, Wang R. Deformation Control Technology for Surrounding Rock in Soft Rock Roadways of Deep Kilometer-Scale Mining Wells. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111911

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Li, Haipeng Li, Lei Ma, Weiming Guan, Haosen Wang, Haochen Feng, Bei Zhang, and Rui Wang. 2025. "Deformation Control Technology for Surrounding Rock in Soft Rock Roadways of Deep Kilometer-Scale Mining Wells" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111911

APA StyleJiang, L., Li, H., Ma, L., Guan, W., Wang, H., Feng, H., Zhang, B., & Wang, R. (2025). Deformation Control Technology for Surrounding Rock in Soft Rock Roadways of Deep Kilometer-Scale Mining Wells. Symmetry, 17(11), 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111911