Abstract

Let be a digraph of order n and let with . A directed -Steiner path (or an -path for short) is a directed path P beginning at r such that . Arc-disjoint between two -paths is characterized by the absence of common arcs. Let be the maximum number of arc-disjoint -paths in D. The directed path k-arc-connectivity of D is defined as In this paper, we shall investigate the directed path 3-arc-connectivity of Cartesian product and prove that if G and H are two digraphs such that , , and , , then moreover, this bound is sharp. We also obtain exact values for for some digraph classes G and H, and most of these digraphs are symmetric.

1. Introduction

For a detailed explanation of graph theoretical notation and terminology not provided here, readers are directed to reference [1]. It should be noted that all digraphs discussed in this paper do not contain parallel arcs or loops. The set of all natural numbers from 1 to n is denoted by . If a directed graph D can be obtained from its underlying graph G by replacing each edge in G with corresponding arcs in both directions, then D is said to be symmetric, denoted as . The notation is used for a symmetric digraph whose underlying graph forms a tree of order n. The notation is used for a symmetric digraph whose underlying graph forms a cycle of order n. The cycle digraph of order n is denoted by . We denote the complete digraph of order n as .

The well-known Steiner tree packing problem is characterized as follows. Given a graph G and a set of terminal vertices , the goal is to identify as many edge-disjoint S-Steiner trees (i.e., trees T in G with ) as feasible. This particular problem, along with its associated topics, garners significant interest from researchers due to its extensive applications in VLSI circuit design [2,3,4] and Internet Domain [5]. In practical applications, the construction of vertex-disjoint or arc-disjoint paths in graphs holds significance, as they play a crucial role in improving transmission reliability and boosting network transmission rates [6]. This paper will specifically delve into a variant of the directed Steiner tree packing problem, termed the directed Steiner path packing problem, closely interconnected with the Steiner path problem and the Steiner path cover problem [7,8].

We now consider two types of directed Steiner path packing problems and related parameters. Let be a digraph of order n and let with . A directed -Steiner path, or simply an -path, refers to a directed path P originating from r such that S is a subset of the vertices in P. Arc-disjoint between two -paths implies that they share no common arcs, while two arc-disjoint -paths are internally disjoint when their common vertex set is precisely S. Let (and ) represent the maximum number of arc-disjoint (and internally disjoint) -paths in D, respectively. The Arc-disjoint (or Internally disjoint) Directed Steiner Path Packing problem is formulated as follows. Given a digraph D and letting , the objective is to maximize the count of arc-disjoint (or internally disjoint) -paths. The notion of directed path connectivity, which is a derivative of path connectivity in undirected graphs, is intricately linked to the directed Steiner path packing problem and serves as a logical progression from path connectivity in directed graphs (refer to [5] for the initial presentation of path connectivity). The directed path k-connectivity [9] of D is defined as

Similarly, the directed path k-arc-connectivity [9] of D is defined as

The concepts of directed path k-connectivity and directed path k-arc-connectivity are synonymous with directed path connectivity. In the context of , equates to and equates to , where and denote vertex-strong connectivity and arc-strong connectivity of digraphs, respectively. Hence, these parameters can be viewed as extensions of the classical connectivity measures in a digraph. It is pertinent to emphasize the close relationship between strong subgraph connectivity and directed path connectivity; refer to [10,11,12] for further insights on this interconnected topic.

It is a widely recognized fact that Cartesian products of digraphs are of great interest in graph theory and its applications. For a comprehensive overview of various findings on Cartesian products of digraphs, one may refer to a recent survey chapter by Hammack [13]. In this paper, we continue research on directed path connectivity and focus on the directed path 3-arc-connectivity of Cartesian products of digraphs.

2. Cartesian Product of Digraphs

Consider two digraphs G and H with vertex sets and . The Cartesian product of G and H, denoted by , is a digraph with vertex set

The arc set of , denoted by , is given by or It is worth noting that Cartesian product is an associative and commutative operation. Furthermore, is strongly connected if and only if both G and H are strongly connected, as shown in a recent survey chapter by Hammack [13].

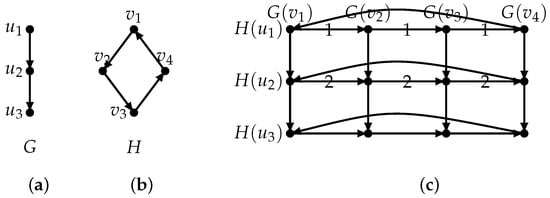

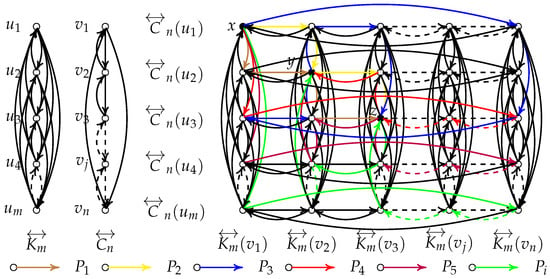

In the rest of the paper, we will use to denote . Additionally, will refer to the subgraph of induced by the vertex set with , while will denote the subgraph of induced by the vertex set with . It is evident that is isomorphic to G and is isomorphic to H. To illustrate this, refer to Figure 1 (this figure comes from [14]), where it can be observed that is isomorphic to G for , and is isomorphic to H for .

Figure 1.

G, H and their Cartesian product [14] (1 denotes arc u1,1u1,2, u1,2u1,3 and arc u1,3u1,4; 2 denotes arc u2,1u2,2, u2,2u2,3 and arc u2,3u2,4).

For distinct indices and with , the vertices and belong to the same digraph , where is an element of . is referred to as the vertex corresponding to in . Similarly, for distinct indices and with , is the vertex corresponding to in . Analogously, the subgraph corresponding to a given subgraph can also be defined. For instance, in the digraph depicted in Figure 1, if we label the path 1 as (and the path 2 as ) in (), then is identified as the path that corresponds to in .

Sun and Zhang proved some results of directed path connectivity, that is, the following lemma.

Lemma 1

([9]). Let D be a digraph of order n, and let k be an integer satisfying . The following statements are valid:

: when .

: .

Lemma 2

([15]).

3. A General Lower Bound

Now we will provide a lower bound for .

Theorem 1.

Let G and H be two digraphs such that , , and , . We have

Furthermore, this bound is sharp.

Proof.

It suffices to show that there are at least or arc-disjoint -paths for any with , . Let and let . Without loss of generality, we may assume and consider the following six cases.

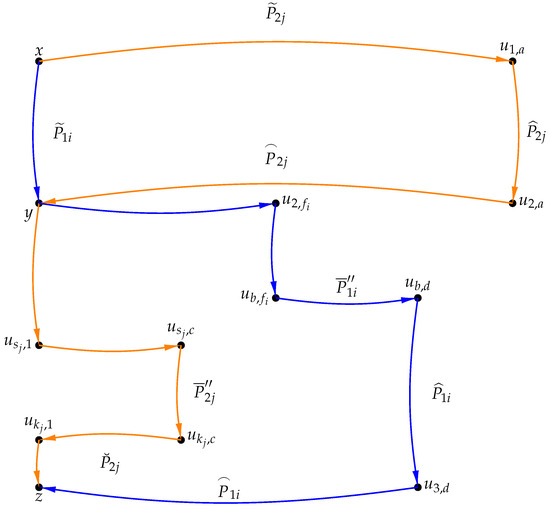

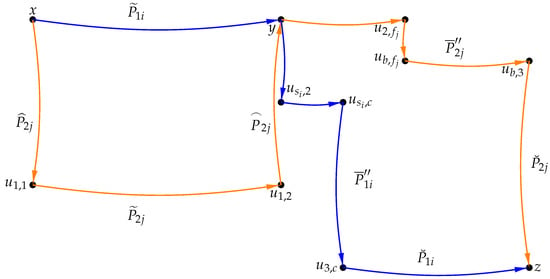

Case 1.

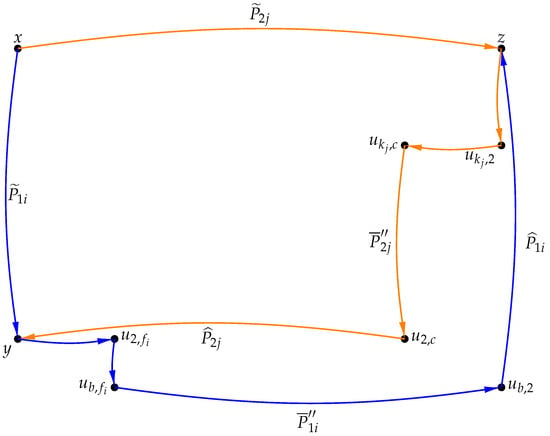

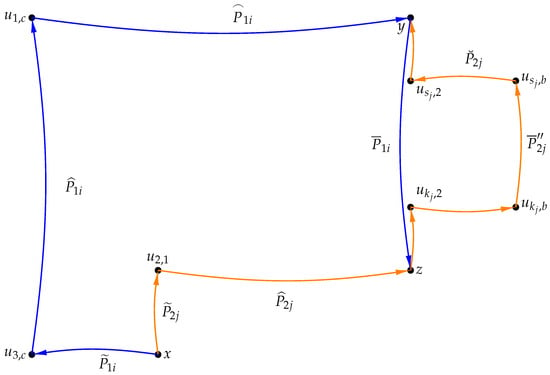

Let x, y and z be in the same or for some , . Without loss of generality, we may assume that , , . In this case, our overall goal is that we will use arc-disjoint paths between x and y in , y and z in , x and its out-neighbors in , y and its in-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , and combine them together to form the required arc-disjoint paths. The general idea of the proof process is briefly described in Figure 2. The vertices and paths contained in Figure 2 are explained below.

Figure 2.

Depiction of the arc-disjoint paths found in Case 1 of the proof of Theorem 1.

Let , . It is known that there are at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . Considering , , there are at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . For each , let be the out-neighbor of y in ; clearly these out-neighbors are distinct. Similarly, an in-neighbor of z in can be chosen such that these in-neighbors are distinct. In , if there is a vertex that is not an out-neighbor of x, then choose such a vertex as , where . If there is no such vertex, that is, all vertices are out-neighbours of x, then choose any vertex as , where . In , let , , and it is established that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, say . In , let , , and it is established that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, say . In , let , , and it is established that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, say .

In , if there is a vertex that is not an out-neighbor of x in , then choose such a vertex as , with . If there is no such vertex, then choose any vertex as , with . In , with and , it is known that there are at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as . For each , let be the out-neighbor of y in ; clearly these out-neighbors are distinct. For each , since , an out-neighbor of in , denoted by , can be chosen, with . If there exists a vertex , let . If there is no such vertex, then let . In , is the -path corresponding to , where , and . In , the path from vertex to is denoted as . Let , , and it is established that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, say . If , then let in . In , let , , and it is established that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, say .

In , if there is an out-neighbor of x that is not an out-neighbor of x in , then choose such a vertex as , with . If there is no such vertex, then choose any out-neighbor of x as , with . And is an out-neighbor of in . In , is the -path corresponding to , where and . In , the path from vertex to is denoted as . If , then . If , then . If , then . In , with , and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths. Then in these paths, one of the paths is chosen, with .

Subcase 1.1.

In the set , there is no vertex such that or , and the vertex z is not in path . We now construct the arc-disjoint -paths by letting

.

Then we obtain arc-disjoint -paths.

Subcase 1.2.

In the set , there is no vertex such that or , and there exist , but there is no arc in path . Let . The other paths are the same as Subcase 1.1.

Subcase 1.3.

There is an arc in path . In the set , there is no vertex x. We can find a path such that . If , then let . If , then let . In and , let and . Let

.

The other paths are the same as Subcase 1.1.

Subcase 1.4.

The set contains the vertex and . There is no arc in . In , there is an arc , . In , there exists an out-neighbor of x, where , and this path is denoted by .

Subcase 1.4.1.

There is no arc in .

In , the path from vertex to is denoted as . In , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths. Then in these paths, one of the paths is chosen, with . If , then let . In , the path from vertex to is denoted as . Let

If , then . The other paths are the same as Subcases 1.1–1.3.

Subcase 1.4.2.

If there exists an arc in , then in , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths. Then in these paths, one of the paths is chosen, with . In , the path from vertex to y is denoted as . Let be the same as in Subcase 1.4.1. Let

The other paths are the same as Subcases 1.1–1.3.

Subcase 1.5.

In the set , there exists vertex . And there is no arc in .

In , there is an out-neighbor of x such that , and this path is denoted by . In , let , , and we know there exist at least internally disjoint -paths. Then in these paths, we choose one of the paths , and let . In , we denote the path from vertex to as . Let

The other paths are the same as Subcases 1.1–1.3.

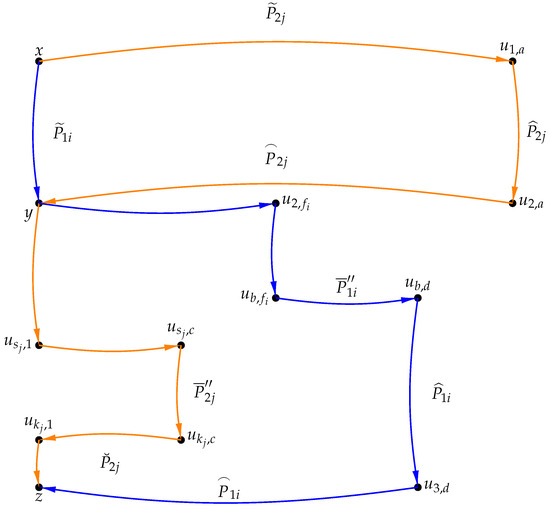

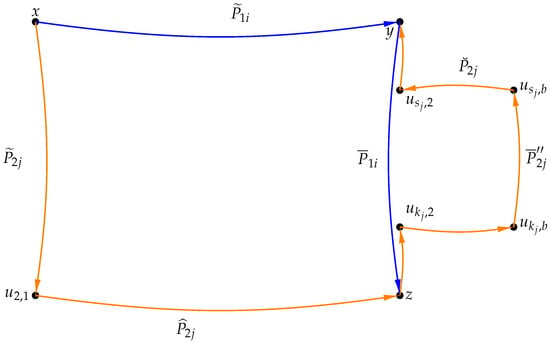

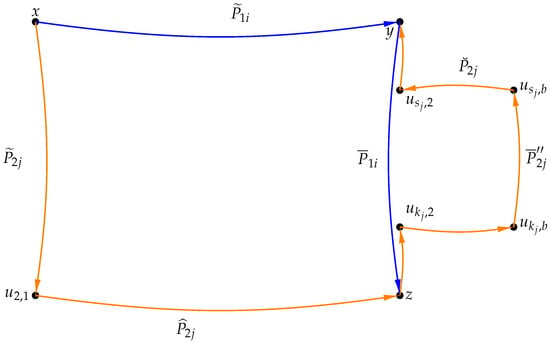

Case 2.

Let x and y be in the same . Let x and z be in the same for some , . Without loss of generality, we may assume that , , . In this case, our overall goal is that we will use arc-disjoint paths between x and y in , y and its out-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , and combine them together to form the required arc-disjoint paths. The general idea of the proof process is briefly described in Figure 3. The vertices and paths contained in Figure 3 are explained below.

Figure 3.

Depiction of the arc-disjoint paths found in Case 2 of the proof of Theorem 1.

Considering , , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . Let , , and there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . For each , let be the out-neighbor of y in ; clearly these out-neighbors are distinct. For each , an out-neighbor of in can be chosen, with . In , with and . is the -path corresponding to . In , the path from vertex to is denoted . With and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . If , then . The arc-disjoint -paths can be constructed as

,

Likewise, we can identify arc-disjoint -paths from x to z and subsequently to y. Consequently, we can derive arc-disjoint -paths.

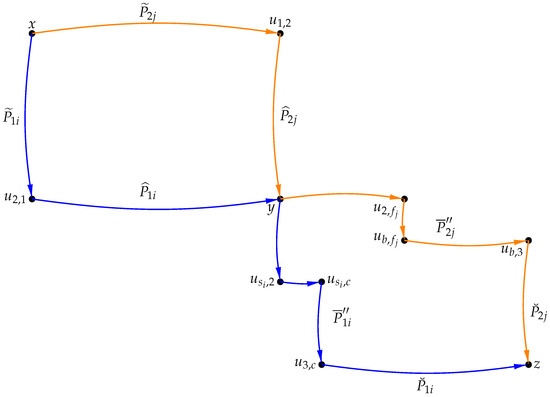

Case 3.

Let x, y and z be in different and for some , . Without loss of generality, we can assume that , , . In this case, our overall goal is that, we will use arc-disjoint paths between x and its out-neighbors in , y and its out-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , x and its out-neighbors in , y and its out-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , and combine them together to form the required arc-disjoint paths. The general idea of the proof process is briefly described in Figure 4. The vertices and paths contained in Figure 4 are explained below.

Figure 4.

Depiction of the arc-disjoint paths found in Case 3 of the proof of Theorem 1.

Considering , , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . Let , , and there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . Considering , , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . Let , , and there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . In , with , , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as . For each , let be the out-neighbor of y in , clearly these out-neighbors are distinct.

In , with , , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . For each , let be the out-neighbor of y in , clearly these out-neighbors are distinct. For each , an out-neighbor of in can be chosen, denoted by , with . Similarly, an out-neighbor of in can be chosen, denoted by , with .

In , with , . is the -path corresponding to . In , the path from vertex to is denoted as . In , with , , and it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, say . In , with , , is the -path corresponding to . In path , the path from vertex to is denoted as . In , with , , and it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , say . If , then . If , then . Similarly, if , then . If , then . The arc-disjoint -paths can be constructed as

Then we obtain arc-disjoint -paths.

Case 4.

Let x and y be in the same . Let z, x, and y be in different and let z, x be in different , for some , . Without loss of generality, we can assume that , , . In this case, our overall goal is that we will use arc-disjoint paths between x and y in , y and its out-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , x and its out-neighbors in , y and its out-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , and combine them together to form the required arc-disjoint paths. The general idea of the proof process is briefly described in Figure 5. The vertices and paths contained in Figure 5 are explained below.

Figure 5.

Depiction of the arc-disjoint paths found in Case 4 of the proof of Theorem 1.

Considering , , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . In , with , and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as . In , with , and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as . In , with , and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as . Let , , , ,, , and be the same as in Case 3.

If , then . If , then . If , then . If , then . If , then .

Subcase 4.1.

If there exists no vertex . Let

Subcase 4.2.

If there exists a vertex , then in , there exists an out-neighbor of x. If , this path is denoted by .

In , there exists an out-neighbor of z such that . In , there exists an in-neighbor of y such that . If , this path is denoted by . Then in , with , and , it is known that there are at least internally disjoint -paths. One such -path is chosen, denoted as , with . In , with , and , it is known that there are at least internally disjoint -paths. One such -path is chosen, denoted as , with . Then, is constructed as

The other paths are the same as Subcase 4.1. Then we obtain arc-disjoint -paths.

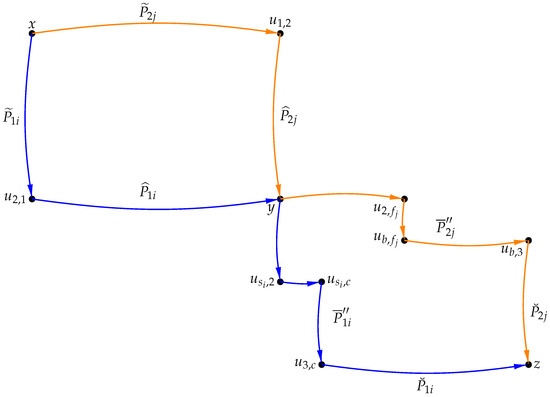

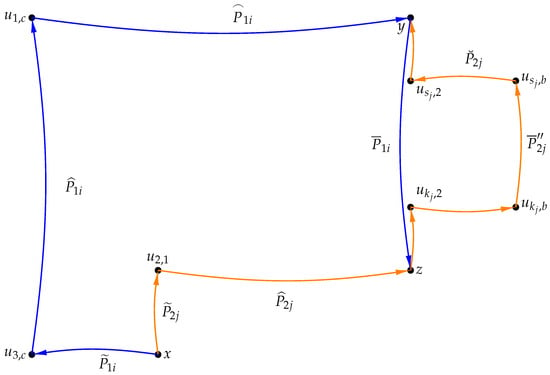

Case 5.

Let x and y be in the same . Let y and z be in the same , for some , . Without loss of generality, we can assume that , , . In this case, our overall goal is that we will use arc-disjoint paths between x and y in , y and z in , x and its out-neighbors in , x and its out-neighbors in , z and y in , and combine them together to form the required arc-disjoint paths. The general idea of the proof process is briefly described in Figure 6. The vertices and paths contained in Figure 6 are explained below.

Figure 6.

Depiction of the arc-disjoint paths found in Case 5 of the proof of Theorem 1.

It is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as , where and . In , there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as , where and . Similarly, in , there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as , where and . In , there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as , where and . In , there exist at least internally disjoint -paths, denoted as , where and . For each , let be the in-neighbor of y in , and clearly these in-neighbors are distinct. Similarly, let be the out-neighbor of z in . For each , an out-neighbor of is chosen in , where .

In , with and . is the -path corresponding to . In , the path from vertex to is denoted as . Then, in , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths. One such -path, denoted as , is chosen, with . The arc-disjoint -paths can be constructed as

If , then . And if , then . This results in obtaining arc-disjoint -paths.

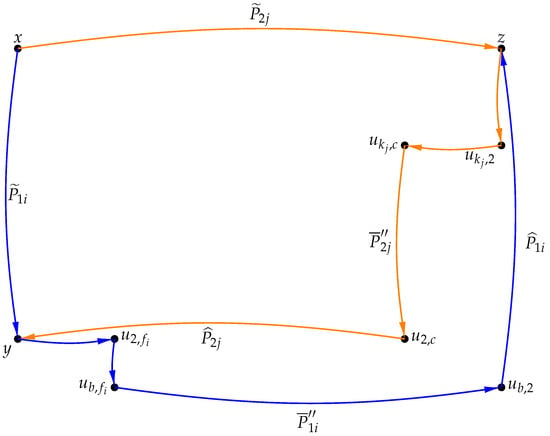

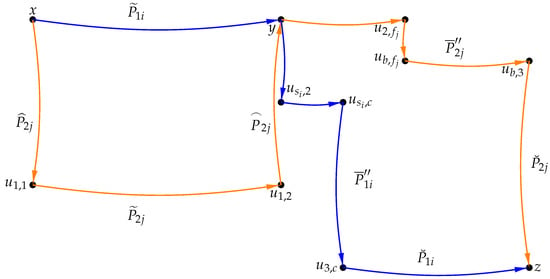

Case 6.

Let y and z be in the same . Let x, y be in different and x, y, z be in different , for some , . Without loss of generality, we can assume that , , . Let , , , , be the same as in Case 5. In , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . In this case, our overall goal is that we will use arc-disjoint paths between x and its out-neighbors in , y and its in-neighbors in , y and z in , x and its out-neighbors in , z and its in-neighbors in , z and y in , and combine them together to form the required arc-disjoint paths. The general idea of the proof process is briefly described in Figure 7. The vertices and paths contained in Figure 7 are explained below.

Figure 7.

Depiction of the arc-disjoint paths found in Case 6 of the proof of Theorem 1.

Subcase 6.1.

In the set , there does not exist . Thus, , , , remain the same as in Case 5.

In , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . In , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . In , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths in , denoted as . If , then . Let

If , then . And if , then . Now we obtain arc-disjoint -paths.

Subcase 6.2.

In the set , only one vertex exists. Thus, , , , remain the same as in Case 5.

If in , then , remain the same as in Subcase 6.1. If an arc is in path , since , then an out-neighbor of can be found in such that and . In , is the -path corresponding to , where , . In , with and , it is known that there exist at least internally disjoint -paths. Then in these paths, one of the paths is chosen, with . and remain the same as in Subcase 6.1. is constructed as

Subcase 6.3.

In the set , there is only one vertex .

For each , an in-neighbor of in can be chosen, denoted by , where . In , let be the -path corresponding to , where , . The path from vertex to in path is denoted as . In , let , , and at least internally disjoint -paths are known to exist. Then, one of the paths is chosen, where . If , . And if , . If in the path . Let

.

If an arc is in path , an in-neighbor of can be found in such that and . In , let be the -path corresponding to , where , . In , let , , and at least internally disjoint -paths are known to exist. Then, one of the paths is chosen, and let . Let

Hence, we obtain arc-disjoint -paths.

Now we prove that this bound is sharp. By Proposition 1, By Lemma 2, . So we have , with . Therefore, the lower bound holds and is sharp. □

4. Exact Values for Digraph Classes

In this section, we aim to determine precise values for the directed path 3-arc-connectivity of the Cartesian product of two digraphs within specific digraph classes.

Proposition 1.

We have

Proof.

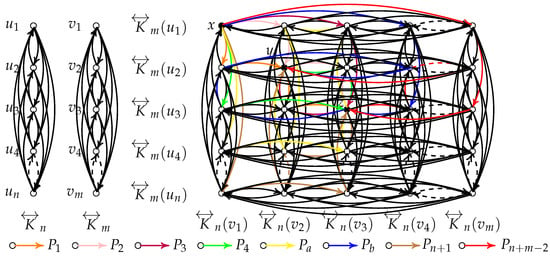

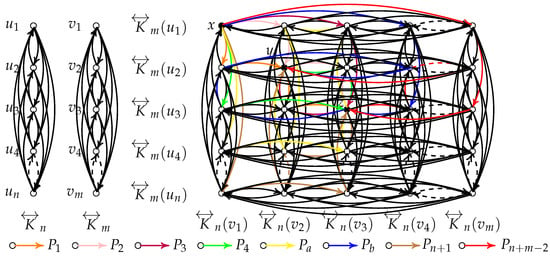

Consider and . We will focus solely on scenarios where x, y, and z do not all belong to the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . It is feasible to derive arc-disjoint -paths in , say , , ⋯, , , ⋯, , (as shown in Figure 8) such that

Figure 8.

.

Now, we add two cases to prove that the proposition holds, so as to show that the proposition has no constraint conditions.

First, let . We can assume that , , . Let

Furthermore, let , . We can assume that , , . Let

Then we have min . This concludes the proof. □

Proposition 2.

We have with .

Proof.

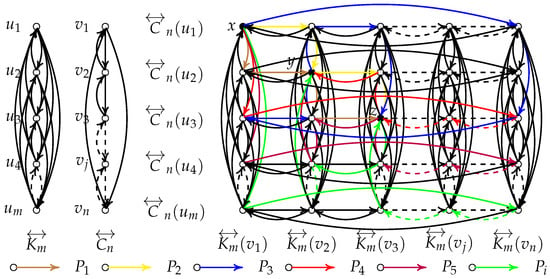

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain arc-disjoint -paths in , say , , ⋯, , , (as shown in Figure 9) such that

Figure 9.

.

Now, we add two cases to prove that the proposition holds, so as to show that the proposition has no constraint conditions.

First, let . We can assume that , , . Let

Furthermore, let , . We can assume that , , . Let

Then we have . This concludes the proof. □

Proposition 3.

We have

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain m arc-disjoint -paths in .

First assume that m is even number, let

, and i is an even number.

Conversely assume that m is odd number, let

, and i is an odd number. Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 4.

We have

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain m arc-disjoint -paths in , say , , ⋯, , , such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 5.

We have

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain two arc-disjoint -paths in , say and such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 6.

We have with .

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain three arc-disjoint -paths in , say , , such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 7.

We have with , .

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain four arc-disjoint -paths in , say , , , such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 8.

We have

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain three arc-disjoint -paths in , say and such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 9.

We have with .

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain three arc-disjoint -paths in , say , , such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

Proposition 10.

We have

Proof.

Let , , and we only examine the case where x, y, and z are not all within the same or the same for any , . The rationale for the remaining cases follows a similar line of argument. Without loss of generality, let us assume , , . We can obtain three arc-disjoint -paths in , say and such that

Then we have . This completes the proof. □

According to Propositions 1–9, we find that the directed path 3-arc-connectivity of some Cartesian products of digraphs is equal to the minimum semi-degrees. Based on this discovery, we can consider under what conditions the directed path 3-arc-connectivity of Cartesian products of digraphs can be equal to the minimum semi-degrees, which is a problem we can consider next.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we prove that if G and H are two digraphs such that , , and , , then and moreover, this bound is sharp. Finally, we obtain exact values of for some digraph classes G and H. In practical terms, constructing vertex-disjoint or arc-disjoint paths in graphs is crucial. These paths play a significant role in improving transmission reliability and boosting network transmission speeds.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this work as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bang-Jensen, J.; Gutin, G. Digraphs: Theory, Algorithms and Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grotschel, M.; Martin, A.; Weismantel, R. The Steiner tree packing problem in VLSI design. Math. Program. 1997, 78, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lee, C.; Gao, H.; Hsieh, S. The internal Steiner tree problem: Hardness and approximations. J. Complex. 2013, 29, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwani, N. Algorithms for VLSI Physical Design Automation, 3rd ed.; Kluwer Acad. Pub.: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Mao, Y. Generalized Connectivity of Graphs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liptak, L.; Cheng, E.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.W. One-to-many node-disjoint paths of hyper-star networks. Discret. Appl. Math. 2012, 160, 2006–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Affash, A.K.; Carmi, P.; Katz, M.J.; Segal, M. The Euclidean bottleneck Steiner path problem and other applications of (α,β)-pair decomposition. Discret. Comput. Geom. 2014, 51, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurski, F.; Komander, D.; Rehs, C.; Rethmann, J.; Wanke, E. Computing directed Steiner path covers. J. Comb. Optim. 2022, 43, 402–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X. Directed Steiner path packing and directed path connectivity. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.04025. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Gutin, G. Strong subgraph connectivity of digraphs. Graphs Comb. 2021, 37, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gutin, G.; Yeo, A.; Zhang, X. Strong subgraph k-connectivity. J. Graph Theory 2019, 92, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gutin, G.; Zhang, X. Packing strong subgraph in digraphs. Discret. Optim. 2022, 46, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, R.H. Digraphs Products. In Classes of Directed Graphs; Bang-Jensen, J., Gutin, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Gutin, G.; Sun, Y. Strong subgraph 2-arc-connectivity and arc-strong connectivity of Cartesian product of digraphs. Discuss. Math. Graph Theory 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yeo, A. Directed Steiner tree packing and directed tree connectivity. J. Graph Theory 2023, 102, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).