1. Introduction

Much use occurs of the physical systems whose parts are kept at different temperatures, i.e., in out-of-thermal-equilibrium conditions. The processes occurring in thermally nonequilibrium systems are usually irreversible, i.e., they lack the symmetry inherent in systems characterized by some unique temperature equal to that of the environment. The theoretical description of thermally nonequilibrium systems is a rather complicated subject. However, the demands of both fundamental physics and its applications in nanotechnology lent impetus to a successful search for new theoretical approaches.

Casimir–Polder interaction is an example of how the standard theory of a thermal equilibrium phenomenon can be extended to out-of-thermal-equilibrium conditions. Casimir and Polder [

1] derived an expression for the force acting between a small polarizable particle and an ideal metal plane kept at zero temperature. In the framework of Lifshitz theory [

2], this result was generalized to the case when an ideal metal plane is replaced with a thick-material plate kept at the same temperature

as the environment [

3,

4]. The Casimir–Polder force is a thermally equilibrium quantum phenomenon determined by the zero-point and thermal fluctuations of the electromagnetic field. It finds extensive applications in atomic physics and condensed matter physics (see the monographs [

5,

6,

7,

8] for a large body of examples). Specifically, much attention is paid to the Casimir–Polder interaction between nanoparticles and material surfaces of different nature, including biomembranes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The extension of Lifshitz theory to physical systems out of thermal equilibrium, which covers both cases of two macroscopic bodies and a small particle near the surface of a macroscopic body, was developed in [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] and further elaborated in [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This was completed under an assumption that each body is in the state of local thermal equilibrium [

22]. The developed theory was confirmed experimentally by measuring the Casimir–Polder force between

87Rb atoms and a fused silica glass plate heated up to the temperatures much higher than

[

33]. The case when the dielectric properties of a plate depend heavily on the temperature offers a fertile field for the study of the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force. This is true for metallic plates [

28,

30] and for plates made of a material that undergoes phase transition with increasing temperature [

29].

The material, which demonstrates a profound effect of temperature on its dielectric properties, is graphene, i.e., a one-atom-thick layer of carbon atoms packed in the hexagonal lattice [

34]. At low energies, graphene is well-described by the Dirac model [

35,

36]. Due to its relatively simple structure, the spatially nonlocal dielectric properties of graphene can be expressed via the polarization tensor in (2 + 1) dimensions [

37,

38] and found on the solid basis of quantum electrodynamics at any temperature [

39,

40,

41,

42]. This presents the immediate possibility to calculate the Casimir–Polder force between nanoparticles and either heated or cooled graphene sheets using the extension of the Lifshits theory to the out-of-thermal-equilibrium situations. Calculations of this kind are of prime interest not only for fundamental physics but for numerous applications harnessing interaction of nanoparticles with graphene and graphene-coated substrates as well (see, e.g., [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]).

The investigation of the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder interaction between nanoparticles and graphene originated in [

49], where the freestanding in vacuum pristine graphene sheet was considered. The pristine character of graphene means that there is no energy gap in the spectrum of quasiparticles, i.e., they are massless, and it possesses the perfect crystal lattice with no foreign atoms. Both these assumptions are in the basis of the original Dirac model of graphene [

34,

35,

36]. According to [

49], the nanoparticles have the same temperature as the environment, whereas the graphene sheet may be either cooler or hotter than the environment, which takes the nanoparticle–graphene system out of the state of thermal equilibrium. It was shown [

49] that the nonequilibrium conditions have a strong effect on the nanoparticle–graphene force and can even change the Casimir–Polder attraction with repulsion if the temperature of a graphene sheet is lower than

.

Taking into account that real graphene sheets are characterized by some energy gap, i.e., small but nonzero mass of quasiparticles [

34], an impact of the energy gap on the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force between a nanoparticle and a freestanding gapped graphene sheet was investigated in [

50]. It was shown that, by varying the energy gap, it is possible to control the force value. Unlike the case of pristine graphene, the force acting on a nanoparticle from the sheet of gapped graphene preserves its attractive character.

When employing graphene sheets in physical experiments or in micro- and nanodevices, they are usually not freestanding in a vacuum but deposited on some dielectric substrate. Because of this, it is important to determine the impact of the substrate underlying the gapped graphene sheet on the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force acting on a nanoparticle. In this article, we investigate the force on a spherical nanoparticle from the source side of dielectric substrate coated with gapped graphene, which is either cooled or heated as compared to the environmental temperature . As to the temperature of nanoparticles, it is assumed to be equal to .

After presenting the main points of the theoretical formalism, we continue with a comparison between the equilibrium Casimir–Polder forces on a nanoparticle from the uncoated and coated with gapped graphene dielectric substrate. Then, the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force acting on a nanoparticle from an uncoated substrate is considered. Next, we turn our attention to the calculation of two contributions of different nature to the nonequilibrium force on a nanoparticle from the graphene-coated substrates with various values of the energy gap of graphene coating kept at different temperatures. Finally, the total nonequilibrium force on a nanoparticle is studied as the function of separation at different temperatures of a graphene-coated substrate and typical values of the energy gap.

It is shown that the presence of a substrate increases the magnitude of the nonequilibrium force, which is larger and smaller than the equilibrium one for a graphene substrate temperature higher and lower than , respectively. In all cases, an increase in the energy gap leads to smaller force magnitudes and to a lesser impact of the graphene coating on the nonequilibrium force on a nanoparticle from the uncoated dielectric substrate.

The article is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the necessary information from the theory of nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force acting on nanoparticles from the substrates coated with gapped graphene. In

Section 3, both the equilibrium and nonequilibrium forces on nanoparticles from the fused silica glass plate are considered and compared with the equilibrium one in the presence of graphene coating. In

Section 4, the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force from a fused silica plate coated with gapped graphene is investigated.

Section 5 contains the discussion. In

Section 6, the reader will find our conclusions.

2. Theoretical Description of Nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder Interaction from

Graphene-Coated Substrates

Here, we briefly present the formalism required for calculation of the Casimir–Polder force between nanoparticles and dielectric substrates coated with gapped graphene in out-of-thermal-equilibrium conditions. We assume that nanoparticles and the environment have the temperature

(in computations, we use

K), whereas the graphene-coated substrate has the temperature

, which may be either lower or higher than

. The separation distance between nanoparticles and the plane surface of area

S of a graphene-coated substrate is

a. The energy gap of a graphene coating is denoted

. Below, we consider the simplest case of spherical nanoparticles whose radius

R satisfies the conditions

where

is the Boltzmann constant. It is suggested also that

.

Nanoparticles of arbitrary shape spaced at any separation from the surface, which should not be necessarily plane, can be considered using the more complicated scattering matrix approach [

24,

27].

It is convenient to represent the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force as a sum of two contributions [

22,

24]

Here,

somewhat resembles the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force expressed as a sum over the discrete Matsubara frequencies, whereas

is the proper nonequilibrium contribution.

Actually, both terms in Equation (

2) describe some part of the effects of nonequilibrium and their explicit forms depend on which of the items responsible for these effects are included in

and which in

. Below, we employ

and

in the forms derived in [

49] and used in [

50]. Thus,

has the form

where

is the static polarizability of a nanoparticle,

k is the component of the wave vector parallel to the plane of graphene,

, the prime on the sum divides the term with

by 2, and the Matsubara frequencies and

are defined as

The quantities

are the reflection coefficients of the electromagnetic waves on the graphene-coated substrate for the transverse magnetic and transverse electric polarizations. In fact, Equation (

3) has the same form as the Lifshitz formula for the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force between a nanoparticle and a plate but with one important difference. Here, the Matsubara frequencies are defined at the environmental temperature

but the reflection coefficients at the temperature of graphene-coated substrate

(in the Lifshitz formula,

). Note also that Equation (

3) contains the static polarizability

in front of the summation sign in

l, whereas in the Lifshitz formula for an atom–wall interaction

appears under the sum in

l. This is because the dynamic polarizability of nanoparticles at several first Matsubara frequencies contributing to the force under the condition (

1) reduces to

[

26].

The proper nonequilibrium contribution

in Equation (

2) is given by [

49,

50]

where

It is presented as an integral over the real frequency axis. In so doing, only

, i.e., only the evanescent waves, contribute to Equation (

5).

In the literature, the other forms of

and

have been considered, where

contains contributions from both the evanescent and propagating waves [

22]. The advantage of Equation (

5) is a presence of the exponential factor with real

q and negative power, which secures the quick convergence of the integral.

The reflection coefficients on the graphene-coated substrate were expressed via the frequency-dependent dielectric permittivity of substrate

and the polarization tensor of graphene

in (2 + 1) dimensions, i.e., with

[

51].

where

For an uncoated substrate

and Equation (

7) transforms into the familiar Fresnel reflection coefficients. To obtain the reflection coefficients at the pure imaginary frequencies entering Equation (

3), one should put in Equation (

7)

. Here, we also assume that the dielectric permittivity of a substrate material does not depend on temperature, contrary to the polarization tensor of graphene. In the case of materials (metals, for instance) with temperature-dependent dielectric permittivity, one should change

in Equation (

7) with

.

Computations of the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force between nanoparticles and graphene-coated substrate can be performed by Equations (

2), (

3), (

5), and (

7) if one knows the explicit expressions for the components of the polarization tensor of graphene. For the gapped graphene, these components defined along both real and imaginary frequency axes were found in [

41] and presented more specifically in [

49,

50] in terms of the variables

and

k. It should be noted, however, that the numerical computations of Equation (

5) along the real frequency axis for substrates coated with gapped graphene are much more involved than those of Equation (

3) and should be performed using the convenient choice of dimensionless variables. That is why, below we introduce the necessary dimensionless quantities and present the results (

5)–(

8) and the expressions for the dimensionless polarization tensor in these terms.

Let us define the following dimensionless quantities

where

Using Equations (

9) and (

10), the reflection coefficients of Equation (

7) can be rewritten as

where

Below in this section, we rewrite the results of [

41,

50] for the polarization tensor in the region of evanescent waves in terms of dimensionless variables (

9) and (

10). It is common to present the polarization tensor as the sum of two contributions

The first terms on the right-hand side of Equation (

13) refer to the case of zero temperature, whereas the second have the meaning of the thermal corrections to them. The polarization tensor in the area of evanescent waves

has different forms in the so-called plasmonic region [

52]

and in the region

where

is the Fermi velocity for graphene and

.

We begin with the plasmonic region (

14). Here, the polarization tensor is also defined differently depending on the fulfilment of some condition. Thus, if the following inequality is satisfied:

the first contributions to the polarization tensor in Equation (

13) are given by

where

is the fine structure constant and

Under the condition of Equation (

16), the second contributions to Equation (

13) take the form

where

From Equations (

17) and (

19), it is observed that, under inequality (

16), the polarization tensor is real.

Next, we continue the consideration of the plasmonic region (

14) but under the inequality opposite to Equation (

16)

In this case, the first contributions to the polarization tensor (

13) take the form

where

The second contributions to Equation (

13) under inequality (

21) take a more complicated form

where

Note that the polarization tensor in the plasmonic region under inequality (

21) is the complex quantity. The first contributions to Equation (

13) defined in Equation (

22) are complex due to Equation (

23). As to the second contributions to Equation (

13) defined in Equation (

24), they are complex due to the square root in the denominators of Equation (

24), which have an imaginary part in the

z interval near

. Much care must be taken regarding this interval in numerical computations.

We come now to the region (

15) and rewrite the results of [

41,

50] for the polarization tensor in terms of the dimensionless quantities (

9) and (

10). In this region, the first contributions to Equation (

13) are

where

The second contributions to Equation (

13) in the region (

15) are expressed as

From Equations (

26) and (

28), it is observed that in the region (

15) the first contributions to the polarization tensor,

and

, are real whereas the second,

and

, are complex.

In the end of this section, we rewrite the proper nonequilibrium contribution (

5) to the Casimir–Polder force in terms of the dimensionless variables (

9), (

10), and (

12)

where

and the reflection coefficients

expressed via the dimensionless variables are contained in Equation (

11).

3. Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder Forces from Fused Silica

Plate Compared to Equilibrium Force in the Presence of Graphene Coating

In this and in the next sections, we use the formalism presented in Section 2 for numerical computations of the Casimir–Polder force acting on a nanoparticle on the source side of the graphene-coated substrate. As the substrate material, we choose fused silica glass,

, which is often used both in applications of graphene in nanoelectronics [

53,

54,

55,

56] and in physical experiments on measuring the Casimir force [

57,

58].

For better understanding of the relative roles of substrate, of nonequilibrium effects, and of graphene coating, in this section we start from calculation of the equilibrium Casimir–Polder forces acting on nanoparticles from the uncoated and coated with gapped graphene substrate. Next, the nonequilibrium force from an uncoated substrate will be computed.

The equilibrium Casimir–Polder force acing on a nanoparticle from both uncoated and graphene-coated

substrates is given by Equation (

3),

where we put

.

If the substrate is uncoated, the reflection coefficients

are given by Equation (

7), where

and

. If the substrate is coated with graphene, one should use Equation (

7) with

. In this case, the polarization tensor of graphene is given by expressions (

26) and (

28) found in the frequency region (

15), where, after returning to the dimensional variables, one can immediately put

(the explicit expressions for the polarization tensor of graphene at the pure imaginary frequencies

are contained in [

59]).

Computations of the equilibrium force

and the contribution

to the nonequilibrium force require the dielectric permittivity of

along the imaginary frequency axis at our disposal, whereas computations of the contribution

to the nonequilibrium force require

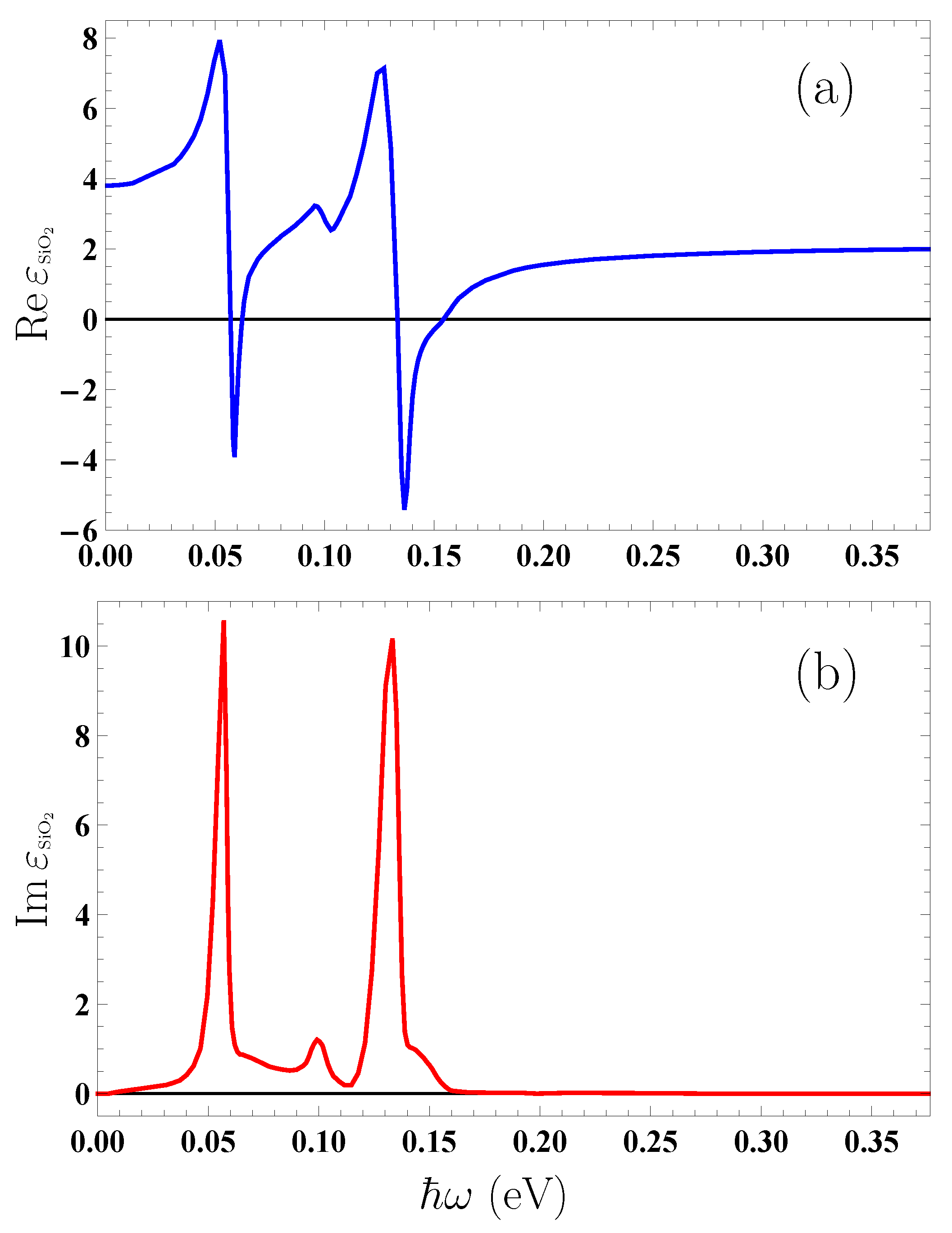

along the axis of real frequencies. In

Figure 1, we present the real (a) and imaginary (b) parts of the dielectric permittivity of

along the real frequency axis plotted by the tabulated optical data for the complex index of refraction of

[

60]. The data collected in [

60] extend from 0.0025 to 2000 eV, whereas in

Figure 1 the most important region for our computations is presented. The values of the dielectric permittivity along the imaginary frequency axis are obtained from

by means of the Kramers–Kronig relations and can be found in many literature sources (see, e.g., [

7]).

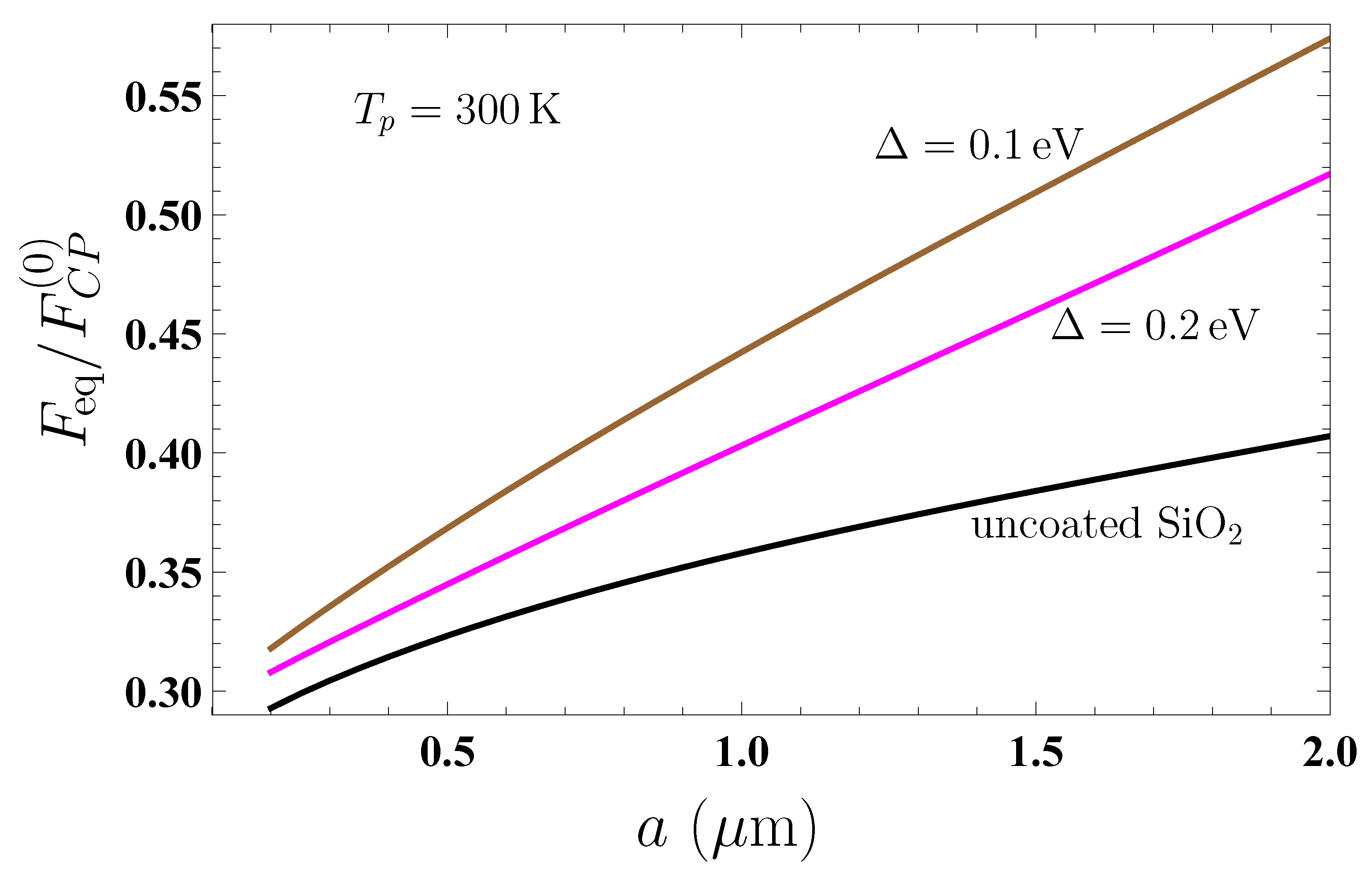

Now, we compute the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force (

31) acting on a nanoparticle from either an uncoated or graphene-coated

plate as a function of separation at the plate temperature

K. Keeping in mind that the force values strongly depend on separation, we normalize them to the Casimir–Polder force on a nanoparticle from the ideal metal plane at zero temperature [

7]

Taking into account that the Dirac model is applicable at energies below 3 eV [

61], we consider the nanoparticle–plate separations exceeding 200 nm where the characteristic energy

is much less than 3 eV. From the above, we restrict the separation region by

m, where the condition (

1) is yet applicable.

In

Figure 2, the computational results for

at

K are shown as the function of separation by the three lines counted from bottom to top for an uncoated

plate and for coated by a graphene sheet with the energy gap

eV and 0.1 eV, respectively (in the two latter cases, the temperature of graphene is

). As shown in

Figure 2, the presence of graphene coating increases the magnitude of the Casimir–Polder force acting on a nanoparticle. This increase, however, is larger for a graphene sheet with smaller energy gap.

To obtain the absolute values of force acting on a nanoparticle, one can use the data of

Figure 2 in combination with the following expressions for the static polarizabilities:

which are valid for dielectric and metallic nanoparticles, respectively [

26]. Thus, for

one obtains

from

Figure 1a.

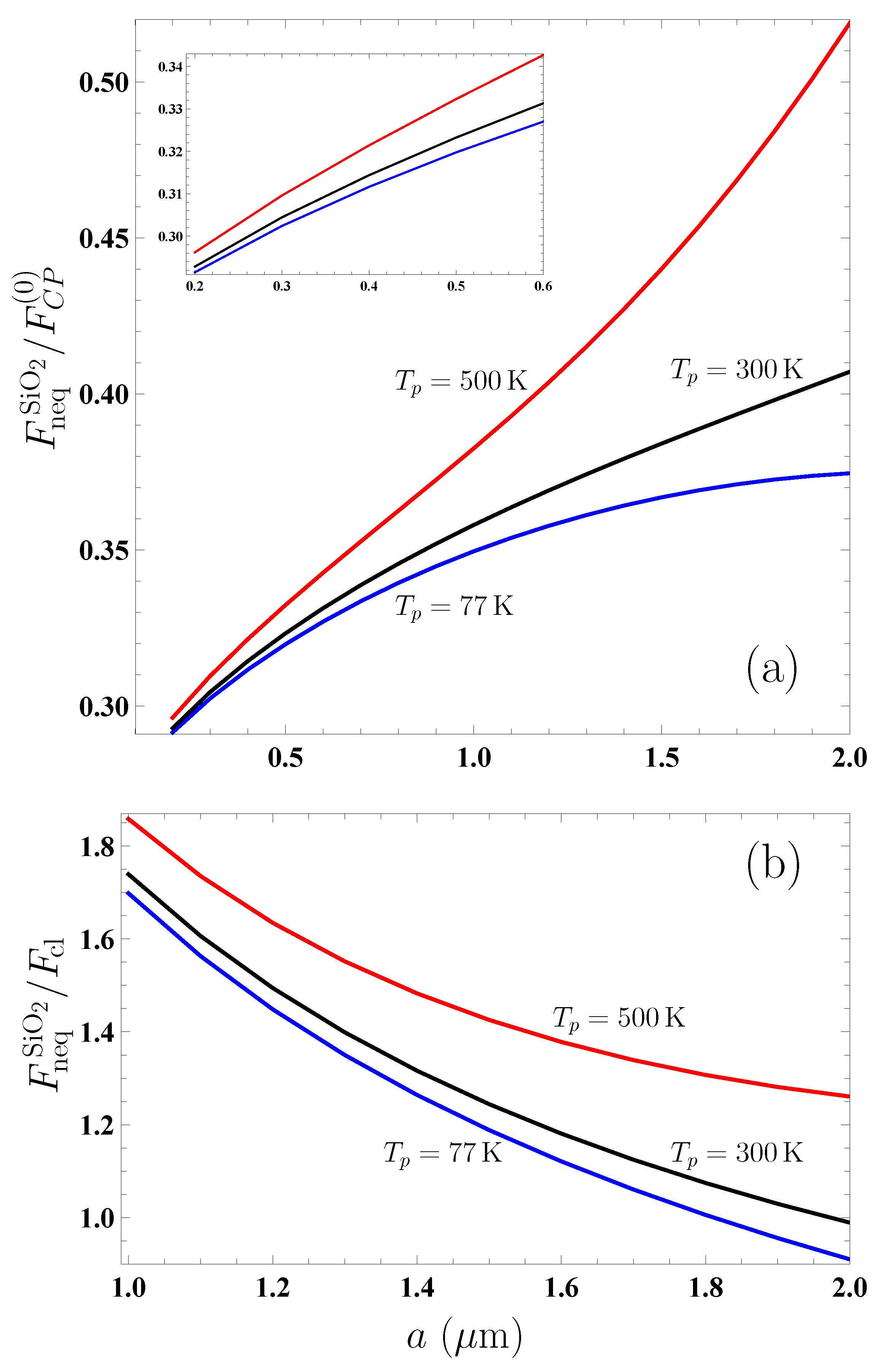

Now, we calculate the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force

acting on a nanoparticle from the uncoated

plate. In so doing, we assume that the plate temperature is either lower,

K, or higher,

K, than the environmental temperature

K. The computations are performed by Equations (

2), (

3), and (

29) with the reflection coefficients (

7), where

in the absence of graphene coating.

Note that the computation of the proper nonequilibrium contribution

to the nonequlibrium Casimir–Polder force, which is performed along the real frequency axis, is much more labor- and time-consuming, especially in the presence of graphene coating (see the next section). These computations were realized by using a program written in the C++ programming language [

50] at the Supercomputer Center of the Peter the Great Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University.

In

Figure 3a, we present the computational results for the ratio

as the function of separation by the bottom and top lines for the plate temperatures

K and 500 K, respectively. For comparison purposes, the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force ratio

for a plate kept at the environmental temperature

K is shown by the middle line, which reproduces the bottom line from

Figure 2. In the inset, the region of small separations from 0.2 to

m is shown on an enlarged scale for better visualization.

From

Figure 3a, it is seen that the effects of nonequilibrium have a strong impact on the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force from a

plate, making its magnitude larger if

and smaller if

. From

Figure 3a, one can also see that at separations exceeding

m the Casimir–Polder force (

32) from an ideal metal plane poorly reproduces the dependence of the nonequilibrium force on the separation distance. Because of this, in the region from 1 to

m, we consider the same computational results for

but normalize them to the thermal Casimir–Polder force from an ideal metal plane at large separations (the so-called classical limit) [

7]

In

Figure 3b, the computational results for the ratio

are shown as the function of separation by the bottom and top lines for the plate temperatures

K and 500 K, respectively. The middle line demonstrates the ratio

in the case of thermal equilibrium

K.

Figure 3b confirms the conclusions already drawn from

Figure 3a. It is also observed that the effects of nonequilibrium due to higher temperature than the environmental one have a greater impact on the equilibrium force than those due to a decrease in temperature to below the environmental one. Further decrease in temperature to below 77 K leads to only an insignificant decrease in the magnitude of nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force.

4. Nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder Force from Fused Silica

Plate Coated with Gapped Graphene

In the previous section, we already considered the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force from a

plate. The main difference in the case of a graphene-coated plate considered now is that the response of graphene to the electromagnetic field described by the polarization tensor strongly depends on temperature. This is not the case for a

plate whose dielectric permittivity is temperature-independent. As a result, for an uncoated

plate, the effects of nonequilibrium influence the force only through the factor

in Equation (

5) defined in Equation (

6).

According to Equation (

2), the total nonequilibrium force is the sum of two contributions,

and

. The first of them has the same form as the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force, whereas the second is the proper nonequilibrium contribution. In order to understand physics of the process, we consider each of them separately starting from

(for an uncoated

plate,

is equal to the equilibrium force at

K shown by the bottom line in

Figure 2 for any temperature of the plate).

Computations of

were performed by Equations (

3) and (

7) and the polarization tensor defined at the pure imaginary frequencies

(see

Section 3 and [

59]). The computational results for the ratio

are presented in

Figure 4a,b as the function of separation for (a) graphene coating with the energy gap

eV and (b) graphene coating with

eV by the bottom and top lines plotted for the graphene (and plate) temperatures

K and 500 K. The middle line shows the ratio

when the graphene temperature is equal to that of the environment,

K.

Unlike the case of an uncoated

plate, in the presence of graphene coating

is not equal to the equilibrium force at

K. As shown in

Figure 4a, for the relatively small energy gap of the graphene coating

eV, the quantity

at

K differs little from the equilibrium force at

K over the entire separation region from 0.2 to

m. Thus, the relative deviation

varies in this case from 1.21% at

m to 1.14% at

m, i.e., is almost independent on separation.

From

Figure 4a, it is also observed that both the middle and top lines grow with separation. This means that, for a substrate coated by graphene with

eV, considerable contribution to both

at

K and

at

K is given by the term of the Lifshitz formula with

. At the same time, for a graphene coating with

eV at

K, the deviation of

from

is much larger and it increases with increasing separation (see the bottom and middle lines in

Figure 4a). Thus, at

m we have

% and at

m already

%.

The comparison of

Figure 4a plotted for a graphene coating with

eV with

Figure 4b plotted for

eV shows that the values of

computed at

K almost coincide (the difference of 0.6% at

m and 1% at

m). This means that at the relatively low

K the thermal corrections are rather small and depend only slightly on the value of

in the range of separations from 0.2 to

m. The comparison of the values of

at

K for graphene coatings with

and 0.2 eV (top lines in

Figure 4a,b) also demonstrates rather small deviations (1% at

m and 1.9% at

m). This is because at such high temperature the thermal corrections are rather large and have only a weak dependence on

. As to the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force at

K, it depends on

more distinctly (compare with

Figure 2). Note also that the magnitudes of

at both 77 K and 500 K are larger than the magnitudes of

from an uncoated

plate at the same respective temperatures. This is observed from the comparison of

Figure 4a,b and

Figure 3.

Next, we consider the second contribution,

, to the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force (

2) acting on a nanoparticle from a graphene-coated substrate. The numerical computations of

were performed in the dimensionless variables by Equations (

11) and (

29) using the polarization tensor in Equations (

17), (

19), (

22), (

24), (

26), and (

28). The computational results for the ratio

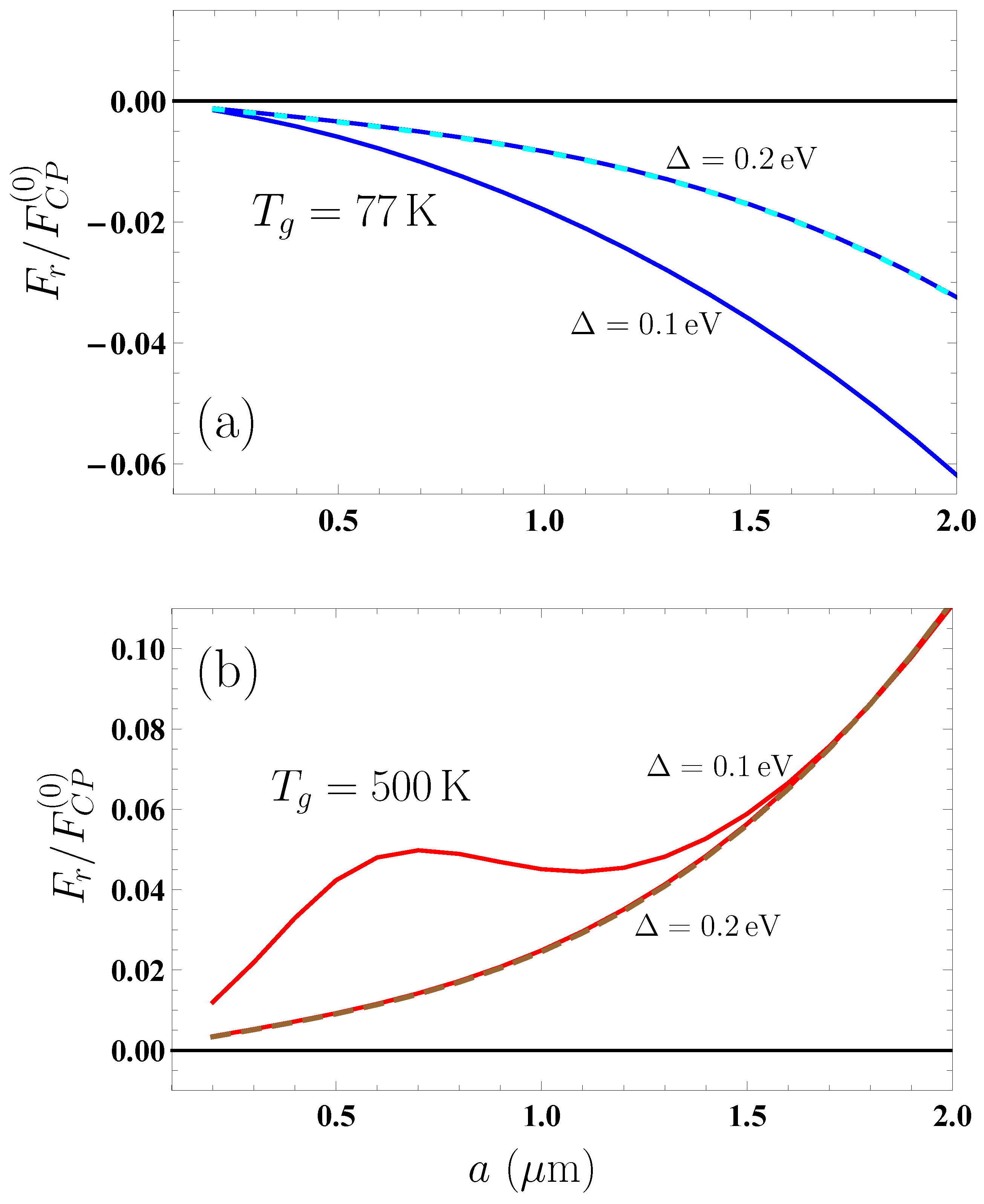

are presented in

Figure 5 as the function of separation for (a) graphene plate temperature

K and (b) graphene plate temperature

K. The solid line in

Figure 5a is plotted for a graphene coating with

eV, whereas another (dashed) line presents the coinciding results for the graphene coating with

eV and for the uncoated

plate. The top and bottom solid lines in

Figure 5b are for a graphene coating with

and 0.2 eV, respectively, and the dashed line is for the uncoated

plate. The form of presentation in

Figure 5a,b provides a way to determine the comparative contributions of the regions (

14) and (

15) to

.

As shown in

Figure 5a,b, the quantity

, unlike

, substantially depends on the value of

at both

and 500 K. The point is that, for

, the contributions to

from the regions (

14) and (

15) are positive, i.e., decrease the force magnitude. The opposite situation occurs for

, i.e., the contributions of Equations (

14) and (

15) to

are negative, leading to the increase in force magnitude.

For the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force acting on a nanoparticle from a freestanding in vacuum graphene sheet, different contributions to

were investigated in [

50]. It was shown that for a graphene with

eV at

K it holds

, whereas for

eV the main contribution to

is given by the region of (

15), which leads to the increase in the force magnitude. If the graphene with

eV is heated up to

K, at short separations (

m) the contribution from the region of (

15) is dominant. With increasing separation, however, the region (

14) takes the main role leading to a minor increase in force magnitude. For a freestanding graphene sheet with

eV, the main contribution to

at all separations is given by the region (

15) [

50].

For a graphene-coated substrate, one has a more complicated situation. The point is that for an uncoated

plate it is just

that determines a distinction of the nonequilibrium force from the equilibrium one. As s result, for an uncoated plate,

for

and

for

. As is seen in

Figure 5a, for

the graphene coating with

eV does not influence the value of

, which is fully determined by the properties of a substrate. However, the graphene coating with

eV has a sizable effect on

.

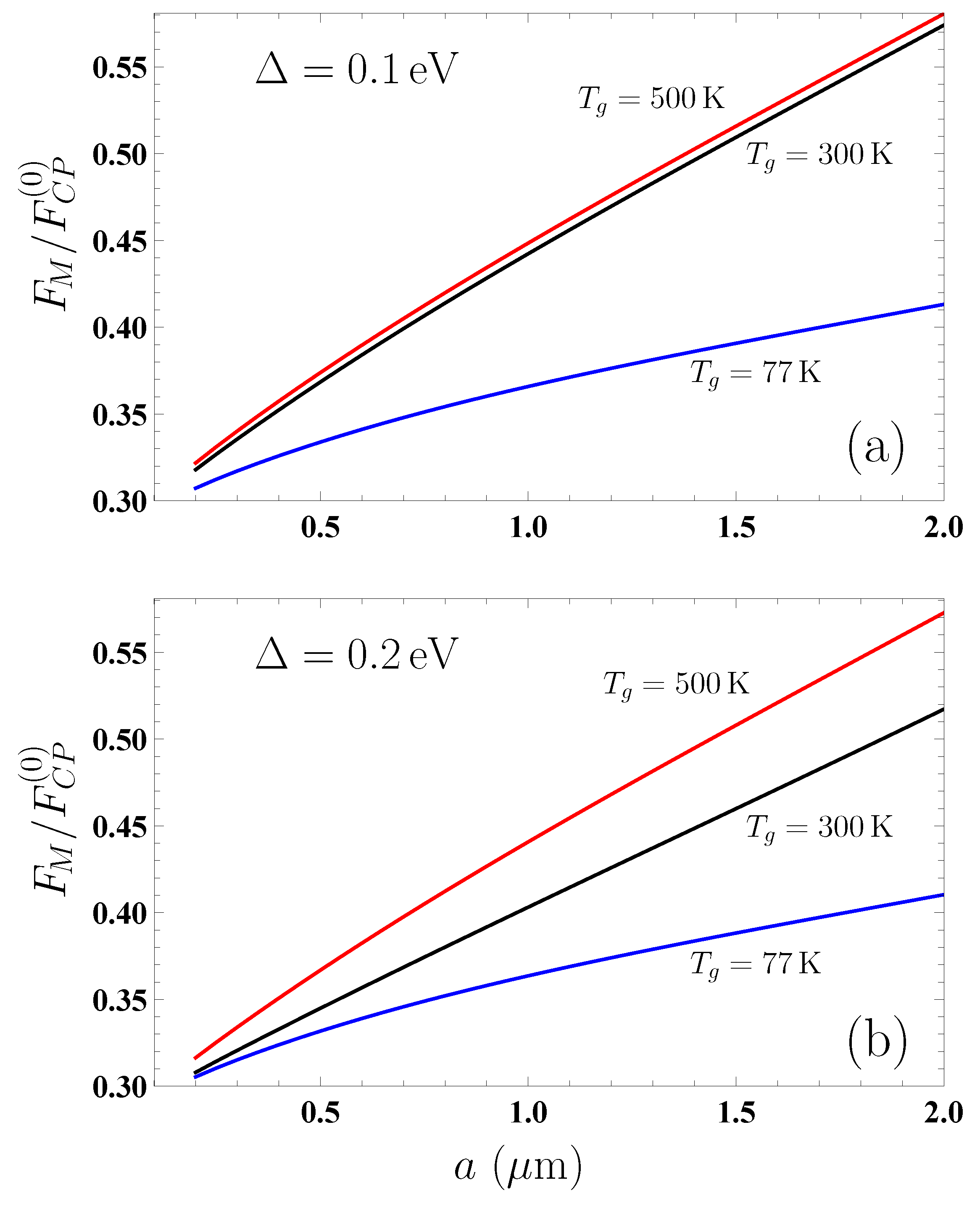

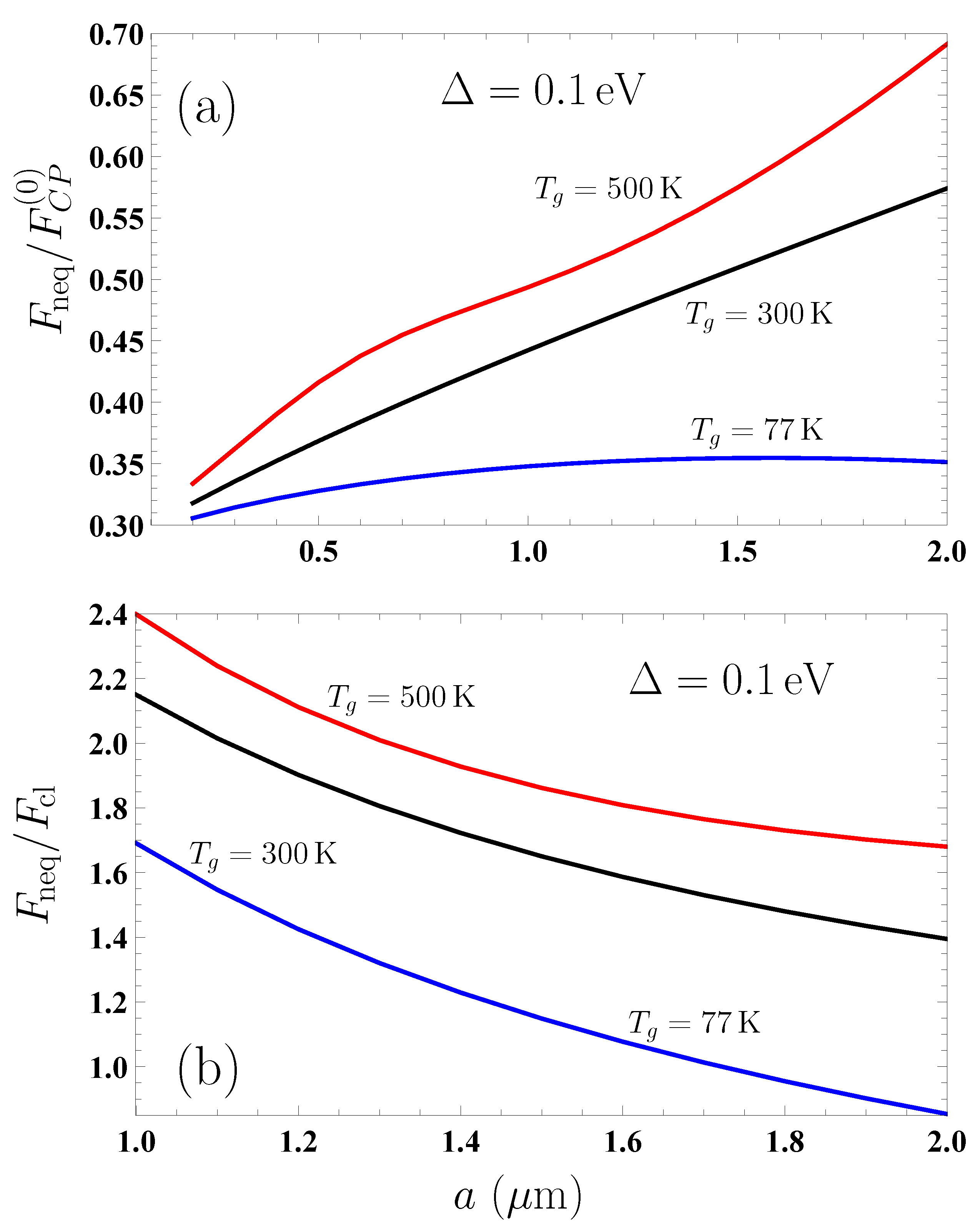

Now, we are in a position to present the computational results for the total nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force

between a nanoparticle and a graphene-coated substrate, which is the sum of contributions

given in

Figure 4 and

given in

Figure 5. In

Figure 6a,b and

Figure 7a,b, the results for

are shown for the graphene coating with

and 0.2 eV, respectively. In each figure, the bottom, middle, and top lines are plotted for the graphene plate temperatures

K, 300 K, and 500 K, respectively. In

Figure 6a and

Figure 7a, the values of

are normalized to the zero-temperature Casimir–Polder force

from an ideal metal plane (

32), whereas, in

Figure 6b and

Figure 7b, they are normalized to the classical limit of the Casimir–Polder force

from an ideal metal plane (

34).

Thus, the middle lines in

Figure 6a and

Figure 7a reproduce the top and middle lines in

Figure 2, respectively, which are also plotted for the equilibrium Casimir–Polder force from the graphene-coated substrate with

and 0.2 eV.

Figure 6b and

Figure 7b can be compared with Figures 1 and 2 in [

50] and plotted there for a freestanding in vacuum graphene sheet in order to determine an impact of the

substrate on the nonequilibrium force. By and large,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 are in analogy to

Figure 3 related to the case of an uncoated substrate.

From

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 it is seen that the nonequilibrium force

from the graphene-coated

plate at both

K and 500 K is larger in magnitude than the force

from an uncoated

plate and from a freestanding graphene sheet. Thus, for a

plate coated with a graphene sheet with

eV at

K, the ratio

is equal to 1.05 and 0.94 at separations

and

m, respectively. The same ratio for the same graphene coating but at

K is equal to 1.12 and 1.33 at the same respective separations. For a graphene coating with

eV at

K the ratio

is equal to 1.04 and 1.01 at

and

m, and, if the graphene-coated plate is at the temperature

K, it is equal to 1.04 and 1.32, respectively.

If we compare the Casimir–Polder force from the graphene-coated plate with that from a freestanding graphene sheet, , it is seen that the presence of a substrate significantly increases the magnitudes of both equilibrium and nonequilibrium forces. This increase is the most pronounced at short separations. As an example, for a graphene coating on a plate and a freestanding graphene sheet with eV, we obtain and 1.4 at and m, respectively. For the nonequilibrium forces with the same value of , the ratio is equal to 8.2 and 2.2 at K and to 4.7 and 1.6 at K at the same respective separations.

The above results allow to control the value of the nonequilibrium Casimir–Polder force acting on nanoparticles from the graphene-coated substrates.