Combination Test for Mean Shift and Variance Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Main Results

3. The Three-Step Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Three-step algorithm |

|

4. Simulations

- •

- For Case 1: The mean and variance are not changed. It can be seen that the empirical sizes of are around the level of significance , while the empirical sizes and of and are smaller than , respectively.

- •

- For Case 2: The mean is changed, while the variance is not changed. It can be seen that the powers of , of , go to 1 as sample size T increases, while the powers of are smaller than 0.025.

- •

- For Case 3: The variance is changed, while the mean is not changed. It can be seen that the powers of , of , increase to 1 as sample size T increases, while the powers of are around .

- •

- For Case 4: The mean and variance are both changed. We can find that the powers of , of , of , go to 1 as sample size T increases.

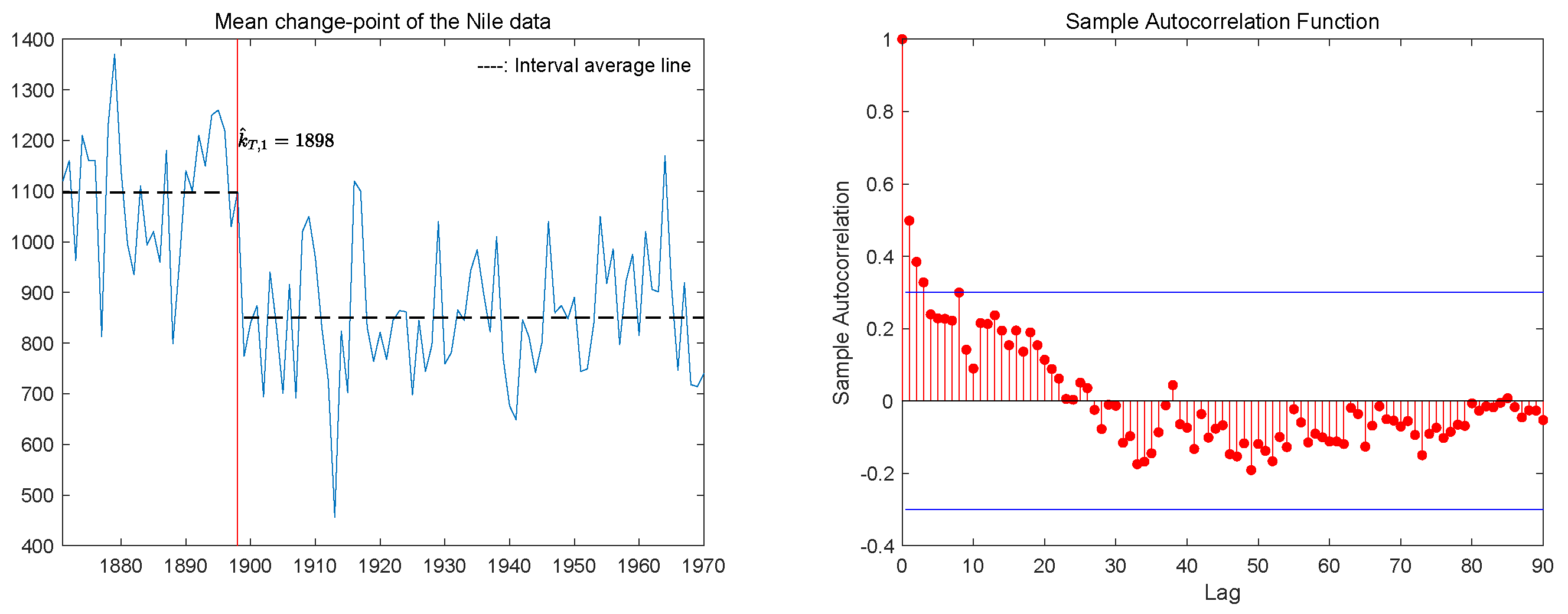

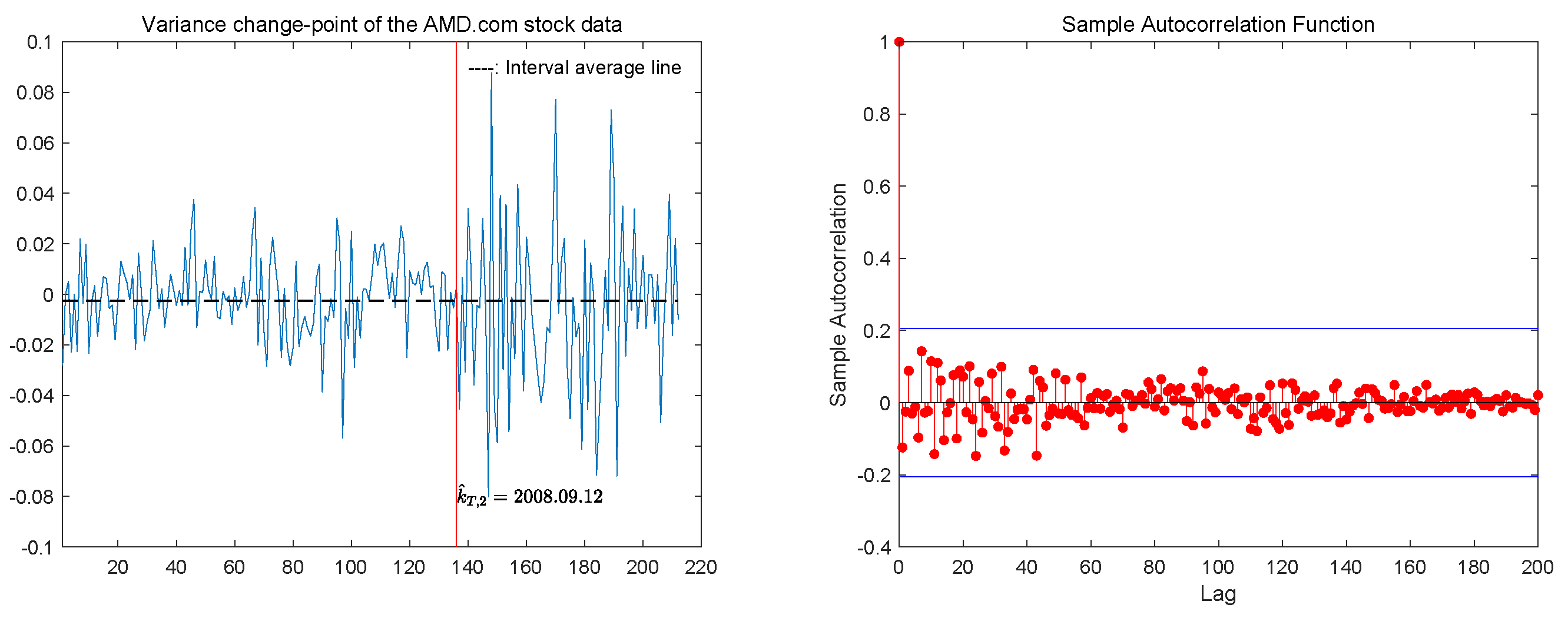

5. The Real Data Analysis

6. Conclusions

7. Proofs of Main Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shewhart, W.A. The application of statistics as an aid in maintaining quality of a manufactured product. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1925, 20, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.S. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika 1954, 41, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoch, J.; Hušková, M.; Veraverbeke, N. Change-point problem and bootstrap. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 1995, 5, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. Least squares estimation of a shift in linear processes. J. Time Series Anal. 1994, 15, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inclán, C.; Tiao, G. Use of cumulative sums of squares for retrospective detection of changes of variance. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1994, 89, 913–923. [Google Scholar]

- Gombay, E.; Horváth, L.; Hušková, M. Estimators and tests for change in variances. Statist. Decis. 1996, 14, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csörgő, M.; Horváth, L. Limit Theorems in Change-Point Analysis; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997; pp. 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Gupta, A. Parametric Statistical Change Point Analysis, with Applications to Genetics, Medicine and Finance, 2nd ed.; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shiryaev, A. On stochastic models and optimal methods in the quickest detection problems. Theory Probab. Appl. 2009, 53, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A. Stochastic Disorder Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 367–388. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, M. A central limit theorem and a strong mixing condition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1956, 42, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killick, R.; Eckley, I.A. changepoint, An R Package for Changepoint Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Kirch, C.; Cho, H. mosum: A Package for Moving Sums in Change-Point Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2021, 97, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoszka, P.; Leipus, R. Change-point in the mean of dependent observations. Statist. Probab. Lett. 1998, 40, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.P.; Wu, Y.H.; Miao, B.Q. Strong convergence rate of estimators of change-point and its application. Comput. Statist. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.S.; Fang, H.Y.; Dong, X.; Yang, W.Z. The CUSUM statistics of change-point models based on dependent sequences. J. Appl. Stat. 2022, 49, 2593–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, S.Y. Inference for mean change-point in infinite variance AR(p) process. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2009, 79, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zhang, X. Testing for change points in time series. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2010, 105, 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X. Self-normalization for time series, a review of recent developments. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2015, 110, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, R. Outliers, level shifts and variance changes in time series. J. Forecast. 1988, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Z.; Liu, H.S.; Wang, Y.W.; Wang, X.J. Data-driven estimation of change-points with mean shift. J. Korean Statist. Soc. 2023, 52, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. Common breaks in means and variance for panel data. J. Econom. 2010, 157, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, L.; Hušková, M. Change-point detection in panel data. J. Time Ser. Anal. 2012, 33, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. Change-point detection in panel data via double CUSUM statistic. Electron. J. Stat. 2016, 10, 2000–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gupta, A. Testing and locating variance change points with application to stock prices. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1997, 92, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, S. The cusum of squares test for scale changes in infinite order moving average processes. Scand. J. Stat. 2001, 28, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wu, Y.; Jin, B. Detection of a change-point in variance by a weighted sum of powers of variances test. J. Appl. Stat. 2019, 46, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, I.; Gombay, E.; Horvath, L. Testing for changes in the covariance structure of linear processes. J. Stat. Plan. Inf. 2009, 139, 2044–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ha, J.; Na, O. The cusum test for parameter change time series models. Scand. J. Stat. 2003, 30, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vexler, A. Guaranteed testing for epidemic changes of a linear regression model. J. Stat. Plann. Inference 2006, 136, 3101–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.S.; Wu, Y.H.; Shi, X.P. Consistent two-stage multiple change-point detection in linear models. Canad. J. Statist. 2016, 44, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, G. Optimal properties of parametric Shiryaev-Roberts statistical control procedures. Comput. Model. New Technol. 2013, 17, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Aue, A.; Hörmann, S.; Horváth, L.; Reimherr, M. Break detection in the covariance structure of multivariate time series models. Ann. Statist. 2009, 37, 4046–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kirch, C. Two-stage data segmentation permitting multiscale change points, heavy tails and dependence. Ann. Inst. Statist. Math. 2022, 74, 653–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Hao, N.; Zhang, H. Multiple change-point detection, a selective overview. Statist. Sci. 2016, 31, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkas, K.; Fryzlewicz, P. Multiple change-point detection for non-stationary time series using wild binary segmentation. Statist. Sinica 2017, 27, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.P.; Wu, Y.H.; Rao, C.R. Consistent and powerful graph-based change-point test for high-dimensional data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3873–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.P.; Wang, X.-S.; Reid, N. A New Class of Weighted CUSUM Statistics. Entropy 2022, 24, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Mamon, R.; Nkurunziza, S. Inference for a change-point problem under a generalised Ornstein-Uhlenbeck setting. Ann. Inst. Statist. Math. 2018, 70, 807–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamba, K.D.; Hawkins, D.M. A multivariate change-point model for change in mean vector and/or covariance dtructure. J. Qual. Technol. 2009, 41, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Lee, S. On score vector-and residual-based CUSUM tests in ARMA-GARCH models. Stat. Methods Appl. 2018, 27, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäntschi, L. A test detecting the outliers for continuous distributions based on the cumulative distribution function of the data being tested. Symmetry 2019, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, K.; Isidore, N. Inference for nonstationary time series of counts with application to change-point problems. Ann. Inst. Statist. Math. 2022, 74, 801–835. [Google Scholar]

- Arrouch, M.S.E.; Elharfaoui, E.; Ngatchou-Wandji, J. Change-Point Detection in the Volatility of Conditional Heteroscedastic Autoregressive Nonlinear Models. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.; Heyde, C.C. Martingale Limit Theory and Its Application; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.Y.; Lu, C.R. Limit Theory for Mixing Dependent Random Variable; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Withers, C.S. Central limit theorems for dependent variables. Z. Wahrsch. Verw. Gebiete. 1981, 57, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrndorf, N. A Functional Central Limit Theorem for Strongly Mixing Sequences of Random Variables. Z. Wahrsch. Verw. Gebiete 1985, 69, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; Domowitz, I. Nonlinear regression with dependent observations. Econometrica 1984, 52, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Györfi, L.; Härdle, W.; Sarda, P.; Vieu, P. Nonparametric Curve Estimation from Time Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.Q.; Yao, Q.W. Nonlinear Time Series. Nonparametric and Parametric Methods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.Z.; Wang, Y.W.; Hu, S.H. Some probability inequalities of least-squares estimator in non linear regression model with strong mixing errors. Comm. Statist. Theory Methods 2017, 46, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, P. Convergence of Probability Measures; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer, J. K-sample analogues of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Cramér-v. Mises tests. Ann. Math. Statist. 1959, 30, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolboacă, S.D.; Jäntschi, L. Predictivity approach for quantitative structure-property models. application for blood-brain barrier permeation of diverse drug-like compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4348–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, C.; Oudre, L.; Vayatis, N. Selective review of offline change-point detection methods. Signal Process. 2020, 167, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balke, N. Detecting level shifts in time series. J. Bus. Econom. Statist. 1993, 11, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis, A.; Kleiber, C.; Krämer, W.; Hornik, H. Testing and dating of structural changes in practice. Comput. Statist. Data Anal. 2003, 44, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Perron, P. An analysis of the real interest rate under regime shifts. Rev. Econom. Statist. 1996, 78, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeileis, A.; Leisch, F.; Hornik, K.; Kleiber, C. strucchange: An R Package for Testing for Structural Change in Linear Regression Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2002, 7, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.0590 | 0.0230 | 0.0190 |

| 600 | 0.0430 | 0.0170 | 0.0120 | ||

| 900 | 0.0520 | 0.0220 | 0.0130 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.0500 | 0.0230 | 0.0120 | |

| 600 | 0.0490 | 0.0170 | 0.0130 | ||

| 900 | 0.0470 | 0.0140 | 0.0150 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.0490 | 0.0120 | 0.0180 | |

| 600 | 0.0440 | 0.0190 | 0.0130 | ||

| 900 | 0.0450 | 0.0170 | 0.0120 | ||

| Case 2 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.9320 | 0.9180 | 0.0130 |

| 600 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0230 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0270 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.6630 | 0.6090 | 0.0170 | |

| 600 | 0.9750 | 0.9730 | 0.0230 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0190 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.3820 | 0.2970 | 0.0200 | |

| 600 | 0.8010 | 0.7680 | 0.0200 | ||

| 900 | 0.9550 | 0.9490 | 0.0150 | ||

| Case 3 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.7920 | 0.0320 | 0.7460 |

| 600 | 0.9910 | 0.0300 | 0.9880 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.0250 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.8890 | 0.0230 | 0.8640 | |

| 600 | 0.9990 | 0.0200 | 0.9980 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.0170 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.8170 | 0.0260 | 0.7630 | |

| 600 | 0.9910 | 0.0230 | 0.9910 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.0220 | 1.0000 | ||

| Case 4 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.9740 | 0.7740 | 0.8000 |

| 600 | 1.0000 | 0.9960 | 0.9960 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.9360 | 0.3930 | 0.8380 | |

| 600 | 1.0000 | 0.8660 | 1.0000 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.9820 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.9790 | 0.7580 | 0.7910 | |

| 600 | 1.0000 | 0.9950 | 0.9950 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| T | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.0530 | 0.0240 | 0.0140 |

| 600 | 0.0470 | 0.0200 | 0.0110 | ||

| 900 | 0.0540 | 0.0220 | 0.0190 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.0490 | 0.0160 | 0.0140 | |

| 600 | 0.0570 | 0.0190 | 0.0160 | ||

| 900 | 0.0420 | 0.0120 | 0.0190 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.0380 | 0.0150 | 0.0100 | |

| 600 | 0.0400 | 0.0140 | 0.0130 | ||

| 900 | 0.0500 | 0.0140 | 0.0200 | ||

| Case 2 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.8130 | 0.7870 | 0.0150 |

| 600 | 0.9550 | 0.9470 | 0.0150 | ||

| 900 | 0.9800 | 0.9770 | 0.0250 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.5890 | 0.5370 | 0.0130 | |

| 600 | 0.8430 | 0.8200 | 0.0220 | ||

| 900 | 0.9310 | 0.9210 | 0.0210 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.3590 | 0.2930 | 0.0200 | |

| 600 | 0.6530 | 0.6200 | 0.0180 | ||

| 900 | 0.7920 | 0.7750 | 0.0180 | ||

| Case 3 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.8160 | 0.0280 | 0.7660 |

| 600 | 0.9960 | 0.0420 | 0.9950 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.0350 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.8890 | 0.0270 | 0.8680 | |

| 600 | 0.9980 | 0.0290 | 0.9980 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.0260 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.8370 | 0.0170 | 0.8050 | |

| 600 | 0.9970 | 0.0160 | 0.9950 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.0280 | 1.0000 | ||

| Case 4 | −0.3 | 300 | 0.9370 | 0.6460 | 0.7750 |

| 600 | 1.0000 | 0.8900 | 0.9900 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.9480 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0 | 300 | 0.9290 | 0.3740 | 0.8390 | |

| 600 | 1.0000 | 0.6860 | 0.9980 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.8600 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0.3 | 300 | 0.8170 | 0.1630 | 0.6990 | |

| 600 | 0.9970 | 0.4700 | 0.9900 | ||

| 900 | 1.0000 | 0.6290 | 1.0000 |

| T | Our Algorithm | cpt.meanvar’s Algorithm | Mosum’s Algorithm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | |||

| 300 | 0.6563 | 0.6518 | 0.6533 | 0.1738 | 0.1738 | 0.1738 | 0.3117 | 0.3117 | 0.3117 | ||

| −0.3 | 600 | 0.8342 | 0.8242 | 0.8275 | 0.6823 | 0.6823 | 0.6823 | 0.6304 | 0.6274 | 0.6284 | |

| Case 2 | 900 | 0.9141 | 0.9011 | 0.9054 | 0.9600 | 0.9595 | 0.9597 | 0.8272 | 0.8242 | 0.8252 | |

| 300 | 0.3656 | 0.3626 | 0.3636 | 0.2088 | 0.2083 | 0.2085 | 0.3467 | 0.3382 | 0.3410 | ||

| 0 | 600 | 0.7223 | 0.7133 | 0.7163 | 0.6294 | 0.6284 | 0.6287 | 0.6364 | 0.6170 | 0.6234 | |

| 900 | 0.8102 | 0.8027 | 0.8052 | 0.8691 | 0.8681 | 0.8685 | 0.7662 | 0.7509 | 0.7559 | ||

| 300 | 0.1469 | 0.1454 | 0.1459 | 0.2238 | 0.2188 | 0.2204 | 0.3526 | 0.3199 | 0.3306 | ||

| 0.3 | 600 | 0.5015 | 0.4950 | 0.4972 | 0.5325 | 0.5253 | 0.5276 | 0.5984 | 0.5098 | 0.5380 | |

| 900 | 0.6783 | 0.6738 | 0.6753 | 0.7522 | 0.7451 | 0.7474 | 0.7253 | 0.6248 | 0.6562 | ||

| 300 | 0.5085 | 0.4980 | 0.5015 | 0.2987 | 0.2977 | 0.2980 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| −0.3 | 600 | 0.8122 | 0.8012 | 0.8049 | 0.7453 | 0.7443 | 0.7446 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Case 3 | 900 | 0.9141 | 0.8966 | 0.9024 | 0.8981 | 0.8981 | 0.8981 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| 300 | 0.6374 | 0.6284 | 0.6314 | 0.3177 | 0.3152 | 0.3160 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| 0 | 600 | 0.8531 | 0.8442 | 0.8472 | 0.7642 | 0.7637 | 0.7639 | 0.0030 | 0.0030 | 0.0030 | |

| 900 | 0.9231 | 0.9156 | 0.9181 | 0.9141 | 0.9126 | 0.9131 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| 300 | 0.5185 | 0.5125 | 0.5145 | 0.3327 | 0.3232 | 0.3263 | 0.0140 | 0.0123 | 0.0128 | ||

| 0.3 | 600 | 0.8042 | 0.7957 | 0.7985 | 0.6993 | 0.6893 | 0.6926 | 0.0290 | 0.0230 | 0.0248 | |

| 900 | 0.8941 | 0.8836 | 0.8871 | 0.8901 | 0.8820 | 0.8846 | 0.0220 | 0.0154 | 0.0174 | ||

| 300 | 0.5285 | 0.6369 | 0.5646 | 0.1828 | 0.3546 | 0.2401 | 0.0794 | 0.1588 | 0.1059 | ||

| −0.3 | 600 | 0.8217 | 0.8247 | 0.8227 | 0.4421 | 0.7794 | 0.5544 | 0.3152 | 0.6274 | 0.4192 | |

| Case 4 | 900 | 0.8971 | 0.8971 | 0.8971 | 0.6528 | 0.8838 | 0.7297 | 0.4136 | 0.8242 | 0.5504 | |

| 300 | 0.3981 | 0.5879 | 0.4614 | 0.2043 | 0.3953 | 0.2679 | 0.1169 | 0.2293 | 0.1543 | ||

| 0 | 600 | 0.7343 | 0.7927 | 0.7537 | 0.4411 | 0.7686 | 0.5500 | 0.3192 | 0.6180 | 0.4187 | |

| 900 | 0.8506 | 0.8591 | 0.8535 | 0.6389 | 0.8590 | 0.7121 | 0.3821 | 0.7504 | 0.5048 | ||

| 300 | 0.5280 | 0.6449 | 0.5669 | 0.2223 | 0.3996 | 0.2813 | 0.1484 | 0.2650 | 0.1870 | ||

| 0.3 | 600 | 0.8327 | 0.8367 | 0.8340 | 0.4291 | 0.6900 | 0.5157 | 0.3157 | 0.5330 | 0.3865 | |

| 900 | 0.9041 | 0.9041 | 0.9041 | 0.5934 | 0.7702 | 0.6517 | 0.0270 | 0.0380 | 0.0304 | ||

| T | Our Algorithm | cpt.meanvar’s Algorithm | Mosum’s Algorithm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | |||

| 300 | 0.5514 | 0.5470 | 0.5485 | 0.0649 | 0.0593 | 0.0611 | 0.1089 | 0.1079 | 0.1082 | ||

| −0.3 | 600 | 0.7622 | 0.7552 | 0.7576 | 0.2777 | 0.2626 | 0.2674 | 0.2577 | 0.2547 | 0.2557 | |

| Case 2 | 900 | 0.8392 | 0.8292 | 0.8325 | 0.5544 | 0.5159 | 0.5275 | 0.3876 | 0.3856 | 0.3863 | |

| 300 | 0.3417 | 0.3402 | 0.3407 | 0.0839 | 0.0755 | 0.0782 | 0.1479 | 0.1449 | 0.1459 | ||

| 0 | 600 | 0.5914 | 0.5844 | 0.5867 | 0.2977 | 0.2770 | 0.2834 | 0.3087 | 0.3022 | 0.3044 | |

| 900 | 0.7163 | 0.7098 | 0.7120 | 0.5355 | 0.5034 | 0.5128 | 0.4815 | 0.4720 | 0.4752 | ||

| 300 | 0.1528 | 0.1503 | 0.1512 | 0.1269 | 0.1149 | 0.1185 | 0.1798 | 0.1635 | 0.1688 | ||

| 0.3 | 600 | 0.4036 | 0.3981 | 0.3999 | 0.3137 | 0.2841 | 0.2929 | 0.3926 | 0.3464 | 0.3614 | |

| 900 | 0.5455 | 0.5380 | 0.5405 | 0.4865 | 0.4487 | 0.4596 | 0.5115 | 0.4668 | 0.4809 | ||

| 300 | 0.5185 | 0.5090 | 0.5122 | 0.2657 | 0.2488 | 0.2539 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| −0.3 | 600 | 0.8122 | 0.7937 | 0.7999 | 0.5345 | 0.5011 | 0.5111 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Case 3 | 900 | 0.9041 | 0.8876 | 0.8931 | 0.6683 | 0.6324 | 0.6427 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| 300 | 0.6104 | 0.6004 | 0.6037 | 0.2827 | 0.2645 | 0.2700 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | ||

| 0 | 600 | 0.8501 | 0.8377 | 0.8418 | 0.5485 | 0.5225 | 0.5305 | 0.0020 | 0.0020 | 0.0020 | |

| 900 | 0.9281 | 0.9166 | 0.9204 | 0.7103 | 0.6640 | 0.6768 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| 300 | 0.5375 | 0.5315 | 0.5335 | 0.2837 | 0.2566 | 0.2649 | 0.0080 | 0.0070 | 0.0073 | ||

| 0.3 | 600 | 0.8482 | 0.8407 | 0.8432 | 0.5105 | 0.4664 | 0.4797 | 0.0230 | 0.0208 | 0.0215 | |

| 900 | 0.9041 | 0.8921 | 0.8961 | 0.6923 | 0.6437 | 0.6580 | 0.0180 | 0.0135 | 0.0148 | ||

| 300 | 0.4770 | 0.6139 | 0.5226 | 0.1538 | 0.2837 | 0.1969 | 0.0260 | 0.0519 | 0.0346 | ||

| −0.3 | 600 | 0.7602 | 0.8072 | 0.7759 | 0.3192 | 0.5548 | 0.3961 | 0.1284 | 0.2532 | 0.1700 | |

| Case 4 | 900 | 0.8546 | 0.8776 | 0.8623 | 0.4191 | 0.6603 | 0.4960 | 0.1938 | 0.3856 | 0.2577 | |

| 300 | 0.3921 | 0.5799 | 0.4547 | 0.1728 | 0.3042 | 0.2157 | 0.0400 | 0.0779 | 0.0526 | ||

| 0 | 600 | 0.6753 | 0.8072 | 0.7193 | 0.3392 | 0.5856 | 0.4197 | 0.1543 | 0.3012 | 0.2033 | |

| 900 | 0.7912 | 0.8581 | 0.8135 | 0.4575 | 0.6846 | 0.5277 | 0.2408 | 0.4720 | 0.3178 | ||

| 300 | 0.2842 | 0.4865 | 0.3516 | 0.1888 | 0.3281 | 0.2343 | 0.0699 | 0.1255 | 0.0884 | ||

| 0.3 | 600 | 0.5375 | 0.7522 | 0.6091 | 0.3362 | 0.5177 | 0.3932 | 0.2078 | 0.3604 | 0.2582 | |

| 900 | 0.6573 | 0.8212 | 0.7120 | 0.4635 | 0.6581 | 0.5228 | 0.2647 | 0.4744 | 0.3335 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, M.; Shi, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, W. Combination Test for Mean Shift and Variance Change. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15111975

Gao M, Shi X, Wang X, Yang W. Combination Test for Mean Shift and Variance Change. Symmetry. 2023; 15(11):1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15111975

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Min, Xiaoping Shi, Xuejun Wang, and Wenzhi Yang. 2023. "Combination Test for Mean Shift and Variance Change" Symmetry 15, no. 11: 1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15111975

APA StyleGao, M., Shi, X., Wang, X., & Yang, W. (2023). Combination Test for Mean Shift and Variance Change. Symmetry, 15(11), 1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15111975