Abstract

This paper investigated the rotation minimizing frames that are related to the space curves and the sweeping surfaces that are traced by these frames in the three-dimensional Lie group. Then, the sufficient and necessary conditions for the sweeping surface to be a developable ruled surface were obtained. In particular, we mostly focused on the study of the resulting developable surface is a cylinder, cone, or tangent surface. Meanwhile, to support the results in the paper, some illustrative examples are presented.

1. Introduction

The common aspects of geometry and algebra, which are two significant subjects of mathematics, are collected Lie groups in two forms: one is that a Lie group is a group, and the second is that it is a differentiable manifold. Thus, the geometric and algebraic framework of Lie groups should be coherent in a specific manner. The study of Lie groups is essential to the common new path to geometry. Therefore, there are numerous study results on curves and surfaces in the three-dimensional Lie group [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

In the Euclidean three-space , the sweeping surface is the surface traced by a continuously moving 2D curve (the generatrix or profile curve) on a spine curve (trajectory) in the space. The outcome of such growth, be it composed of movement in the space or substantial shape distortion, is a sweep subject. The sweep subject type is specified by the choice of the generator and the position. Sweeping surfaces are a considerable and essential types of surfaces in geometric modeling and are universally used in industrial design, which shows why these surfaces are one of the charming subjects of surface theory, as well as being applied in many areas of science such as computer-aided geometric design, computer-aided design, and so on [8,9,10,11,12]. One of the paramount facts about the sweeping surface is that the sweeping surface can be a developable ruled surface [13,14]. Developable surfaces are the distinctive ruled surfaces that are rather interesting and have many applications in many subjects. Therefore, many geometers and engineers have investigated and obtained many properties of the ruled and developable surfaces (see, for example, [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]). However, to the authors’ knowledge, there is no work devoted to discussing the notions of sweeping surfaces immersed in Lie groups.

In this study, we investigated how to design sweeping surfaces using the rotation-minimizing frames in the three-dimensional Lie group. Then, we investigated the necessary and sufficient conditions for the sweeping surface to turn into a developable ruled surface to establish the Bishop frame along a unit speed curve and develop the local differential geometry of the sweeping surface in the three-dimensional Lie group . Then, we summarize some results concerning the differential geometry of the sweeping surfaces that are generated by these frames. Consequently, we give the necessary and sufficient conditions for the sweeping surface to be a developable ruled surface. We also investigated the uniqueness of such developable surfaces. In particular, we mainly focused on the study of the resulting developable surface to be a cylinder, cone, or tangential surface. Finally, some examples of its applications are introduced and explained in detail.

Hopefully, these results will lead to a connection with the similarities between the theory of the sweeping surfaces in Euclidean three-space and with that in the three-dimensional Lie group.

2. Preliminaries

This section gives an introduction to Lie group theory (see [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]). Consider to be a Lie group with a bi-invariant metric <, > and ∇ to be the Levi-Civita connection of . If indicates the Lie algebra of , then is isomorphic to where e is the identity (neutral) element of . For any three vector fields , , and in , we have the following:

and:

Let be an arc-length smooth curve and {, ,...,} be an orthonormal basis of . In this case, any two vector fields and can be written as and , where , : are smooth functions. The Lie bracket of and is given by:

and the directional derivative of on the curve is given as follows:

where and , where . It is necessary to note that if is the left-invariant vector field to the curve, then (see for details [14,15,16,17,18]). Here, a “dash” denotes the derivative with respect to the parameter s.

Let be a regular curve in the three-dimensional Lie group with the Serret–Frenet system {, , , , . Then, a smooth function , which is called Lie torsion, is defined by:

and:

Proposition 1.

Let α be an arc-length parametrized curve in . Then,

In view of Equation (2) and Proposition 1, the Serret–Frenet formulas of in are written as:

where and .

Remark 1.

Let be a three-dimensional Lie group with a bi-invariant metric. Then:

(1) If is the special orthogonal group (3), then ;

(2) If is the special unitary group (2), then ;

(3) If is a commutative (Abelian) group, then .

Bishop Frame or Rotation-Minimizing Frame

From the Serret–Frenet formulas, we see that:

is the instantaneous dual Darboux vector along the curve . This vector allows writing the Serret–Frenet formulas as:

Definition 1.

A moving orthonormal frame , , through a space curve in , is a rotation-minimizing frame (RMF) with respect to if its angular velocity ω satisfies , or equivalently, the derivatives of and are both parallel to . A similar description holds when or is selected as the reference orientation [10,17,18].

In view of Definition 1, we see that the Serret–Frenet frame is an RMF with respect to the principal normal , but not with respect to the tangent (resp. the binormal ). However, the Serret–Frenet frame is not an RMF with respect to , and one can simply obtain such an RMF from it. The new normal plane vectors (, ) are given through a rotation of (, ) according to:

with a certain angle . Here, we call the set , the RMF or Bishop frame. Thus, the Bishop formulae are:

where is the Bishop Darboux vector. Furthermore, the Bishop curvatures are defined by , . One can show that:

where is the initial value of s. In this study, we supposed that . Comparing Equation (6) with Equation (8), we see that the relative velocity is:

This proves that the Serret–Frenet frame has an extra revolution along the tangent, whose speed equals . This shows that the integral formula of Equation (9) for evaluating the RMF results in the undesirable rotation of the Serret–Frenet frame. Therefore, we have the following:

Corollary 1.

Assume is a regular curve with the arc-length parameter s in and , , , κ, comprise its Serret–Frenet apparatus. Then, the Serret–Frenet frame is obtainedalong with the RMF if and only if the binormal vector is a constant vector field, that is .

3. Sweeping Surfaces in the Three-Dimensional Lie Group

Kinematically, the concept of a sweeping surface is generated by a plane curve moving over the space such that the motion of any point on the surface is constantly orthogonal to the plane. Hence, by using the RMF frame, the sweeping surface family in is given by [13]:

where is called the spine curve. Here, the planar profile (cross-section) curve is specified by the parametric exemplification , where the character “t” represents transposition, with different parameters . The particular orthogonal matrix , is assignedto the RMF along .

Without loss of generality, we can suppose the profile curve is a unit speed curve, that is, . In the next, we use “dot” to indicate the derivative with respect to the arc-length parameter of the profile curve . It is readily checked that the two tangent vectors of M are given by:

The first fundamental form is then given by:

where:

The surface unit normal vector is given by:

By a simple derivation, we have:

This leads to the elements of the second fundamental form , , and , where:

Hence, the t and s curves of M are curvature lines, that is . Thereby, the isoparametric curve:

is a 2D unit speed curvature line. Equation (16) determines a family of planes. The unit tangent vector to is:

and consequently, the unit principal normal vector of is:

From Equation (18), it is interesting to note that the surface normal is identical to the principal normal , that is the curve is a geodesic 2D curvature line on . Surfaces for which parametric curves are curvature lines have numerous implementations in geometric design [9]. In the case of sweeping surfaces, one has to evaluate the offset surfaces of a given surface at a constant distance f. As a result of this equation, the offsetting procedure for the sweeping surface can be performed more easily than the offsetting of the 2D profile curve, which is much easier to deal with.

Proposition 2.

Let a sweeping surface M be defined by Equation (10). Assume is the planar offset of the 2D profile at distance f. Then, the offset surface is still a sweeping surface, defined by the spine curve and the 2D profile curve .

3.1. Local Singularities

Singularities are fundamental for the realization of the sweeping surfaces and are inspected next: It can be seen that the sweeping surface M has singular points if and only if:

where is the curvature radius of . Using , we have the correlations:

We can obtain the singular curve of M as follows:

We mention that singular points happen at the intersection amidst the 2D profile curve and the instantaneous axis of rotation:

Corollary 2.

Assume that M is a sweeping surface Equation (10), with the profile and spine curves having non-vanishing curvatures anywhere. Then, M has no singular points if:

is satisfied for all s and t.

The conditions that guarantee the convexity or curves that produce parabolic points of a surface are desired in various implementations (such as manufacturing of sculpted surfaces or layered manufacturing). Therefore, we discuss in what conditions the parametric curves are parabolic curves as follows: The Gaussian curvature of M at a regular point can be obtained as:

Let be the angle between the normal of the isoparametric curve t=const. and be the normalof the surface M, then we have:

where:

Since every generating 2D profile curve is a curvature line for the sweeping surface, the value of one principal curvature is:

Furthermore, the curvature of the parametric curves . is:

In order to describe the shape of M, we attempted to obtain the curves on M that are traced by parabolic points, that is points with zero Gaussian curvature. These curves divide the elliptic (, locally convex) and hyperbolic (, hence non-convex) parts of the surface. As a result of Equation (26), there three cases emerge when parabolic points are considered:

Case (1) exists when . If , the 2D profile curve is turned into a straight line, and from Equation (24), it can be seen that:

This equation shows that a flat or inflection point of forms a parabolic curve const. on parts of the sweeping surface.

Case (2) exists when . From Equation (25), it can be found that if , then . This means that the spine curve is turned into a straight line. Likewise, a flat or inflection point of the spine curve forms a parabolic curve const. on parts of the sweeping surface.

Case (3) exists when . From Equation (22), it can be found that if , hence . Then, the curve is not only a curvature line, but also an asymptotic of the sweeping surface. Thus, for the parabolic points, the condition:

is satisfied for all s and t. Thus, the following corollary can be given:

Corollary 3.

Consider M to be a sweeping surface Equation (10), with the profile and spine curves having non-vanishing curvatures everywhere. Then, M has parabolic points if and only if the spine curve is an asymptotic curve.

By the integration of Equation (28), the following can be acquired:

where is an arbitrary function. Then, we have the relationships:

Therefore, from Equation (10), it follows that the parabolic curve is:

Corollary 4.

Consider M to be a sweeping surface Equation (10), with the spine and profile curves having non-vanishing curvatures everywhere. Then, M has precisely one parabolic curve if and only if the spine curve is an asymptotic curve.

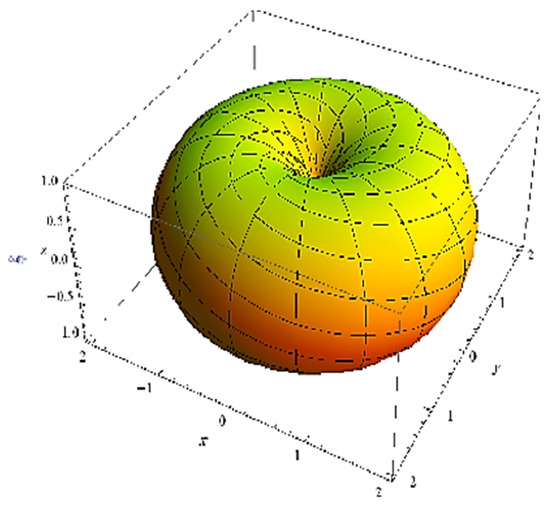

Example 1.

Let the spine curve be:

For this curve,

where and . Then , and the Bishop curvatures are, respectively, as follows:

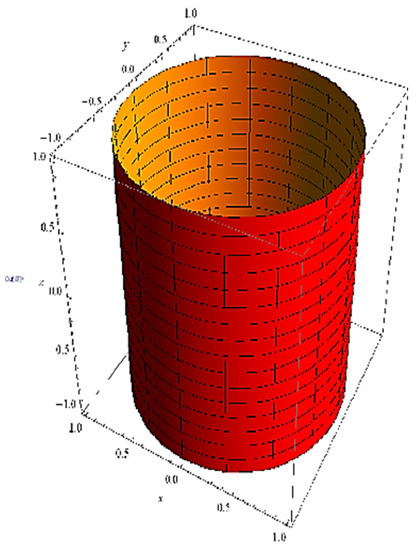

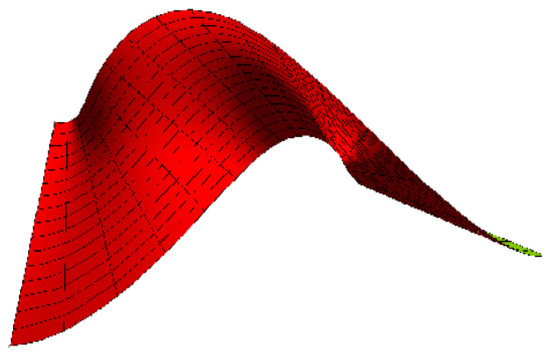

If we consider , then we obtain a member of the sweeping surface family in the special orthogonal group (3), as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Sweeping surface over a circle.

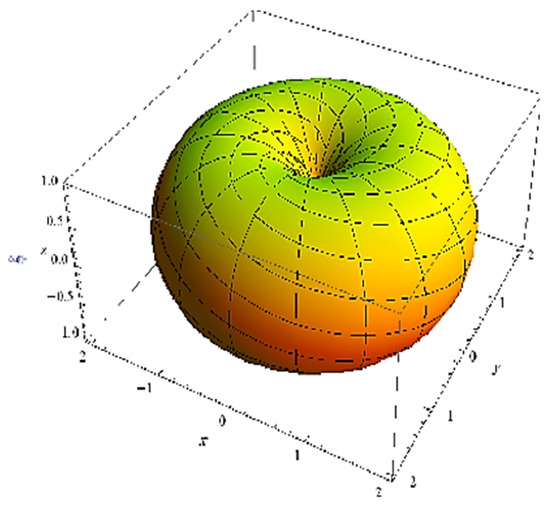

Example 2.

Let the spine curve be:

Then,

where , . Then, , and:

Similarly, we obtain:

from which we have:

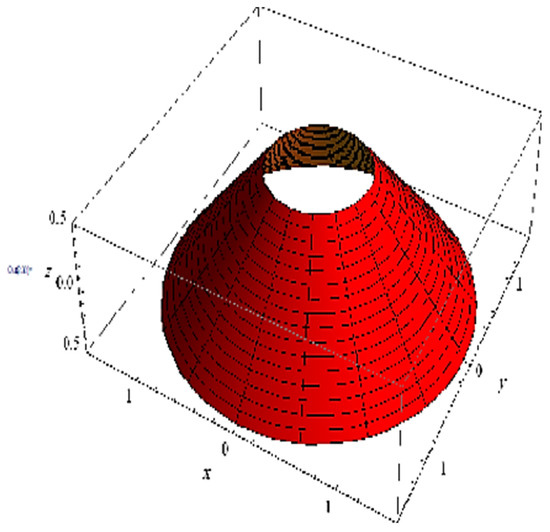

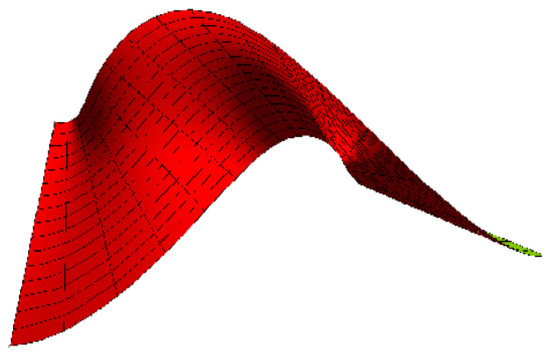

If we consider , then we obtain a member of the sweeping surface family in a commutative group as shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Sweeping surface over a helix.

3.2. Developable Surfaces

Developable surfaces are curved surfaces developing on planes without tearing and stretching. The significance of such surfaces is illustrated in manufacturing and engineering applications such as automobile components, ship hulls, and apparel modeling (see, e.g., [13,14,15,16]). Therefore, we analyzed the case in which the profile curve degenerates into a line. Then, we have two developable surfaces as follows:

and:

Moreover,

and:

Then, M (resp. ) is the normal developable surface of (resp. M) along , and is a curvature line of M (resp. ).

Proposition 3.

Let M be a sweeping surface Equation (10); if the profile curve degenerates into a straight line, then M is a developable surface.

Theorem 1

(Existence and uniqueness). Under the above notations, there exists a unique developable surface Equation (32).

Proof.

For the existence, we have the developable surface Equation (32). On the other hand, since M is a ruled surface, we assume that:

It can be instantly seen that M is developable if and only if:

Further, we have:

where is a differentiable function. In addition, the normal vector at the point is:

In analogous arguments for , we can give the corresponding Theorem 1, and we omit the details here. Thus, the Joachimsthal theorem in can be stated as follows:

Theorem 2

(Joachimsthal). Let M and be two developable surfaces in such that is a regular curve and along , where and are unitary normal vector fields to M and , respectively. Then, is a curvature line of M if and only if it is a curvature line of .

As a utility (such as cylindrical or flank milling), through the movement of the RMF, consider a cylindrical cutter that is rigidly linked to this frame. Hence, the equation of a family of cylindrical cutters, which is traced by the movement of a cylindrical cutter along , can be obtained as follows:

where indicates the cylindrical cutter’s radius. This surface is a developable surface offset of the surface . The equation of can therefore be written as:

The normal vector of the cylindrical cutter can be represented as:

On the other hand, we can rewrite Equation (42) as:

Moreover, we have:

from which is orthogonal to the normal vector . Furthermore, the vector is orthogonal to the tool axis vector . Hence, the developable surface and the envelope surface of the cylindrical cutter have a common normal vector, and the length between the two surfaces is the cylindrical cutter’s radius .

Therefore, we conclude the following:

Proposition 4.

If the developable surface Equation (32) possessing as a curvature line and the envelope surface of the cylindrical cutter are regular, the two surfaces are offset developable surfaces.

Regarding curves with developable surfaces, we studied the conditions when the developable surface M is a cylinder, cone, or tangent surface, respectively.

Theorem 3.

The developable surface Equation (32) in is a cylinder surface if and only if .

Proof.

M is a cylindrical surface if and only if:

Since is a non-zero unit vector, then M is a cylinder if and only if:

□

Remark 2.

In Theorem 3, by , we know or π. However, in any case, we have , then . Therefore, in terms of the Serret–Frenet formulas in , we have that is a constant vector, the curve is a planar curvature line, and M is a binormal surface.

Theorem 4.

The developable surface Equation (32) is a cone if and only if , where and .

Proof.

The first derivative of the directrix is:

where is the first derivative of the striction curve and is a regular function. Then, M is a cone if and only if the striction curve degenerates into a point, that is . This means that:

Hence, by equating the coefficients of and , , this implies that:

where and . □

In Theorem 4, we have that if is a constant, that is , then the curve is a planar curvature line with a constant curvature. Similarly, if is also a constant, we can have , and is also constant. Then, the curve is the arc of a circle.

Theorem 5.

The developable surface Equation (32) is tangential developable if and only if , where and .

Proof.

According to the proof of Theorem 4, when , we have . Since det( , and , then . This means that M is tangential developable. □

3.3. Examples

In this subsection, we confirm the correctness of the formulae obtained above.

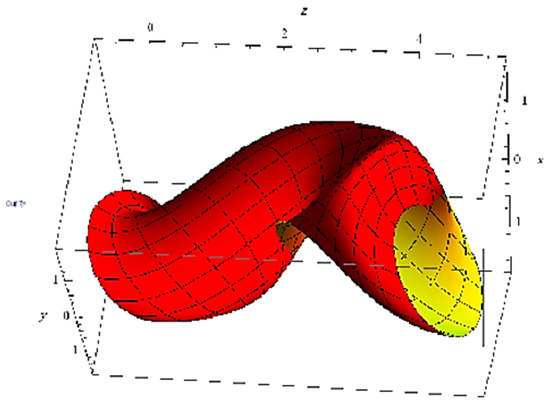

Example 3.

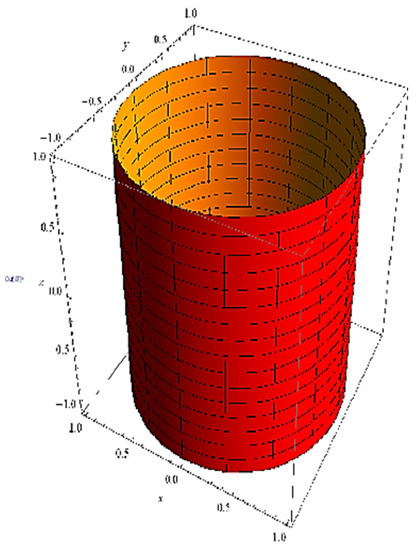

Based on Example 1, we construct a cylinder in with the following equation (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

A right cylinder.

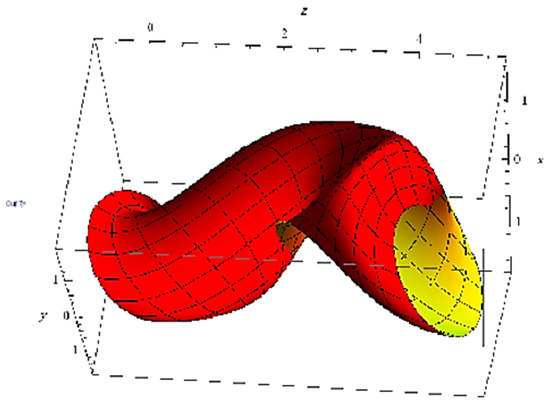

Obviously, it does not satisfy Theorem 3, that is . This means that a cylinder in a commutative group is developable, but a cylinder in a three-dimensional Lie group is not developable. More explicitly, since , then is a constant. If or π, the developable surface is a cylinder. If we take for example, then M is shown in Figure 3. Take for example; the developable surface:

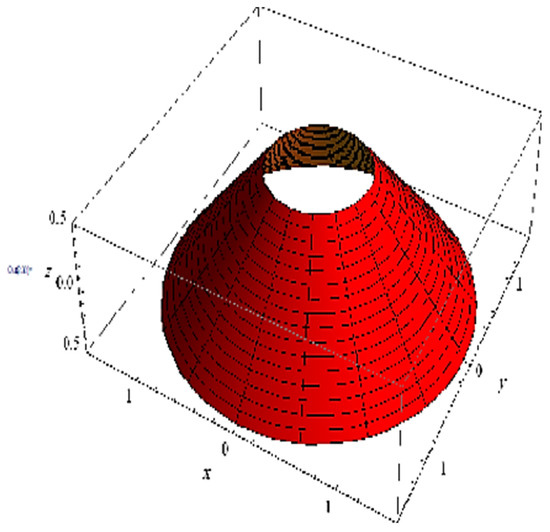

is a cone (Figure 4). Then, we state the following: in the three-dimensional Lie group, there exists no developable cylinder (resp. cone) surface possessing a given planar curve as a curvature line.

Figure 4.

A circular cone.

Example 4.

Based on Example 2 and Theorem 3, we have . Then, the developable surface:

is a tangential developable surface in a commutative group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A tangential developable.

4. Conclusions

In the three-dimensional Lie group , we developed a new mathematical framework for finding a sweeping surface family. We also showed that the parameter curves are curvature lines and gave their Gaussian curvatures. This led us to study their geometric properties and local singularities. In the process of the derivation, the necessary and sufficient conditions when the resulting sweeping surface is a developable ruled surface were also analyzed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.N. and R.A.A.-B. methodology, S.H.N. and R.A.A.-B. investigation, S.H.N. and R.A.A.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.N. and R.A.A.-B.; writing— review and editing, S.H.N. and R.A.A.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yoon, D.W. General helices of AW (k)-type in the Lie group. J. Appl. Math. 2012, 2012, 535123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, D.W.; Tuncer, Y.; Karacan, M.K. On curves of constant breadth in a 3-dimensional Lie group. Acta Math. Univ. Comen. 2016, 85, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, D.W. Classifications of special curves in the Three-Dimensional Lie Group. Int. J. Math. Anal. 2016, 10, 503–514. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyucu, O.Z.; Yıldız, O.G.; Tosun, M. Spinor Frenet equations in three dimensional Lie Groups. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras 2016, 26, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yüzbası, Z.K.; Yoon, D.W. On constructions of surfaces using a geodesic in Lie group. J. Geom. 2019, 110, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, A. New type direction curves in 3-dimensional compact Lie group. Symmetry 2019, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, D.W.; Yüzbası, Z.K. A generalization for surfaces using a line of curvature in Lie group. Hacet. J. Math. Stat. 2021, 50, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo, M.P. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pottmann, H.; Wallner, J. Computational Line Geometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Jüttler, B.; Zheng, D.; Liu, Y. Computation of rotating minimizing frames. ACM Trans. Graph. 2008, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.H.; Kim, Y.H. Some Classification of canal surfaces with the Gauss map. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2019, 42, 3261–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.A.; Mahmoud, W.M.; Solouma, E.M.; Bary, M. The new study of some characterization of canal surfaces with Weingarten and linear Weingarten types according to Bishop frame. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 2019, 27, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdel-Baky, R.A. Developable surfaces through sweeping surfaces. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2019, 45, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Baky, R.A.; Mofarreh, F. Sweeping surfaces according to type-2 Bishop frame in Euclidean 3-space. Asian-Eur. J. Math. 2021, 14, 2150184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Y.; Wang, G.J. A new method for designing a developable surface utilizing the surface pencil through a given curve. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2008, 18, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Wang, R.H.; Zhu, C.G. An approach for designing a developable surface through a given line of curvature. Comput.-Aided Des. 2013, 45, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.L. There is more than one way to frame a curve. Am. Math. Mon. 1975, 82, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouki, R.T.; Giannelli, C.; Sampoli, M.L. Rotation-minimizing osculating frames. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2011, 31, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).