Abstract

There is increasing interest in two-dimensional and quasi-two-dimensional materials and metamaterials for applications in chemistry, physics and engineering. Some of these applications are driven by the possible auxetic properties of such materials. Auxetic frameworks expand along one direction when subjected to a perpendicular stretching force. An equiauxetic framework has a unique mechanism of expansion (an equiauxetic mode) where the symmetry forces a Poisson’s ratio of . Hinged tilings offer opportunities for the design of auxetic and equiauxetic frameworks in 2D, and generic auxetic behaviour can often be detected using a symmetry extension of the scalar counting rule for mobility of periodic body-bar systems. Hinged frameworks based on Archimedean tilings of the plane are considered here. It is known that the regular hexagonal tiling, , leads to an equiauxetic framework for both single-link and double-link connections between the tiles. For single-link connections, three Archimedean tilings considered as hinged body-bar frameworks are found here to be equiauxetic: these are , , and . For double-link connections, three Archimedean tilings considered as hinged body-bar frameworks are found to be equiauxetic: these are , , and .

1. Introduction

Auxetic materials and metamaterials are of technical and theoretical importance, with a spectrum of potential and realised applications [1,2,3,4,5,6], and they play a pivotal role in the theoretical explanation of rigidity and mobility in periodic systems [7,8]. This is a rapidly growing area of research; for example, if we limit our attention to those proposed metamaterials that are auxetic, the review [1] cites over 270 references relevant to this sub-field. An auxetic structure is defined by the initially surprising property of expanding along one direction when stretched along a perpendicular direction [9,10]. There is a considerable literature of experimental, theoretical and modelling work on such structures, e.g., [11,12,13,14,15]. One interesting subset of auxetics consists of those that have symmetric behaviour: equiauxetic structures have a Poisson’s ratio of . Thus, they display the auxetic property for all directions of stretch [16].

A symmetry treatment of mobility in periodic structures [17] has been adapted for the detection of equiauxetic behaviour [16] and applied to an extensive catalogue of 2D bar-and-joint frameworks in which rigid bars along polygon edges pivot freely at mutual joints [18]. This symmetry criterion has also been used to study equiauxetic mechanisms in hinged tilings: structures where the polygonal tiles of a tessellation of the plane are treated as rigid bodies connected by one, or sometimes more, pin-jointed bars per tile–tile edge contact. The three regular tilings of the plane by hexagons, squares and triangles have been studied in this context [19], yielding insight on the extent to which mobility properties of periodic systems can be deduced from finite physical models.

Many tiling-like patterns appear in structural chemistry, and many chemical realisations have been investigated because of the interest in 2D layer materials inspired by the discovery of graphene [20]. Layer materials now have their own journals, e.g., FlatChem, 2D Materials, and 2D Materials and Applications, and the properties of these materials are attracting interest from both theoreticians and experimentalists. One Archimedean tiling made up of carbon atoms appears in the 2D projection of the hypothetical auxetic carbon allotrope, pentagraphene [21,22], and another in the putative superconductor, T-graphene [23]. Some biomaterials can also be modelled as tilings: the regular square tiling appears in an auxetic layer material constructed from self-assembled pin-jointed aldolase tetramers [24]. Other constructions based on tilings connected by hinges have attracted interest in the mathematical literature [25]. Modifications of hinge tilings and lattices in practical application are also of current interest [26,27,28].

Here we investigate the extension of the symmetry treatment of equiauxeticity to Archimedean tilings, which are defined as vertex-transitive, edge-to-edge tilings of the plane with at least two types of regular polygonal tile. Some authors [29] use the term Archimedean inclusively to cover both semi-regular and regular tilings, but here we restrict its use to the non-regular cases. Our tilings are hinged, and in the first case of interest, they have a single link (pin-jointed bar) for each edge of the closed tiling, with one end pinned to each of the rigid contacting tiles, arranged with a consistent sense of rotation for all tiles. Eight such single-link hinged Archimedean tilings exist, of which one has mirror-image forms in 2D. Bar lengths are taken to be generic up to symmetry, i.e., equal for symmetrically equivalent edges but otherwise arbitrary. Established symmetry techniques, with extensions to deal with non-transitivity of edges and dependence of mobility counts on unit-cell size, turn out to be informative for these non-regular tilings.

In the earlier work on hinged regular tilings [19], both double- and single-link tilings were studied. Double-link connection with equivalent bars imposes an additional condition, in that the edges of neighbouring polygons must remain parallel. Regular tilings are edge-transitive, and the parallel constraint is therefore guaranteed for a totally symmetric expansion. However, of the Archimedean tilings, only the Kagome lattice is edge-transitive. As shown below, results for the mobility of these double-link hinged Archimedean tilings are obtained by minor modification of the character-table calculation for the single-link structure.

Finally, we note that finite analogues of the hinged tilings, the hinged expanding polyhedra (or expandohedra), have been studied in a symmetry context as models for deployable structures that occur in nature and engineering [30,31]. Structures such as cowpea chlorotic mottle virus and dengue virus, respectively, are known to undergo conformational transitions under the influence of changes in pH [32] and temperature [33]. Hinging of rigid subunits gives models for transitions of both types.

2. Theory

2.1. Mobility of Body-Bar Frameworks

The structures considered here are 2D body-bar frameworks, consisting of rigid bodies connected by pin-jointed bars. For n bodies connected by b bars, the Tay counting rule [34] gives the net mobility (the number of mechanisms, m, minus the number of states of self-stress, s) in two dimensions as

This equation for a finite 2D body-bar framework has symmetry-extended version [35]:

and a further extension to periodic systems [19]

The detailed reasoning leading to the last equation is given elsewhere [17]; the process is essentially one of allowing for freedoms of the bodies, removing rigid-body motions of the whole lattice, applying the (scalar) constraints imposed by the bars, and excluding motions that are disallowed for a 2D periodic framework.

The notation used in (2) and (3) requires some brief explanation. In 2D, the representations and refer to the rigid-body motions of frameworks in the plane: the two independent translations within the plane and the single rotation about the normal to the plane. The general notation (object) denotes the reducible representation of a set of objects, consisting of the vector of characters in which, for a finite structure, each entry gives the number of objects unshifted under operation R. In periodic calculations, the objects counted under a given operation are either unshifted or shifted to translationally equivalent positions. If the objects have vector or tensor characters, the resolution of components onto their original positions must also be considered. The permutation representations and describe the symmetries of the vertices and edges of a contact polyhedron C [36], which has vertices at body centres and an edge for each bar-constraint linking a pair of bodies.

In the present case, this so-called contact ‘polyhedron’ is infinite and is combinatorially equivalent to the dual of the tiling, i.e., to a Laves tiling [29]. As in previous work [17], all representations are to be calculated in the finite group obtained by factoring out translations from the infinite wallpaper group that describes the 2D periodic structure; the group is isomorphic to a point group. The groups appropriate to the Archimedean tilings are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Archimedean tilings and symmetry groups. In the first column, tilings are labelled by the vertex symbol in a nomenclature recommended by [37], which describes the cyclic sequence of faces around a vertex, much as the Schläfli symbol does for polyhedra [38]. The tiling group is the 2D wallpaper group [29], . The linked tiling belongs to the maximum rotational subgroup, . The point group is formed by factoring out translations from .

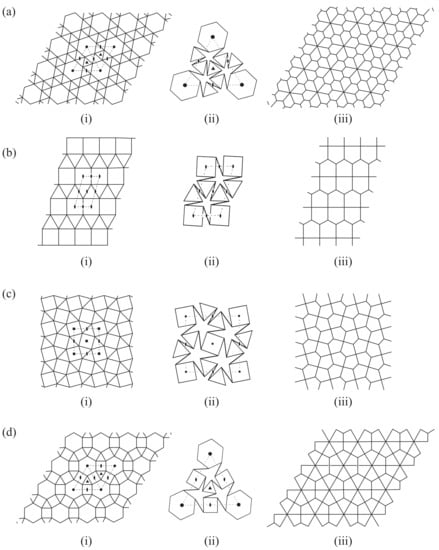

For hinged tilings, on the introduction of links following a consistent sense of rotation, the symmetry is reduced to a pure rotational group, isomorphic to a cyclic group, , where n is the order of the principal axis. These groups are abelian but with separable degeneracy and complex irreducible representations for . Standard sets of point-group tables [39,40,41] are available for the calculation of all the necessary representations. Figure 1 shows for each case: the Archimedean tiling, a portion of that tiling in a partially expanded state along an auxetic pathway, and the dual Laves tiling that corresponds to the infinite ‘contact polyhedron’. The figure is drawn for the ‘regular’ choice of geometry, where all edges are of equal length.

Figure 1.

Archimedean tilings and mobility of their single-link hinged versions. Panels (a–h) show (i) the closed tiling, (ii) a sample of an auxetic expansion mode, and (iii) the dual Laves tessellation. Rotational symmetry elements of orders 2, 3, 4, 6 are indicated by conventional symbols, ▴, ▪. The order in which tilings are presented in Table 1.

2.2. Equiauxetic Systems

Equation (3) can be applied to periodic systems to give a symmetry condition sufficient for equiauxeticity. The symmetry criterion for equiauxetic behaviour [16] is that the reducible representation for the net mobility, , should include, with positive weight, one or more irreducible representations of of A or B type (i.e., non-degenerate, and hence with character, respectively, or under the principal rotation operation in , which should be of order 3, 4 or 6). These correspond to symmetry-detectable equiauxetic modes. They can be identified by a standard tabular calculation [42], as used below.

The totally symmetric representation of a group is a special case of type A, in that it has character under all operations of that group motion along any A or B mode, with the exception of the totally symmetric representation, is a distortion that results in halving of the group, with the result that the distortion mode becomes totally symmetric in the smaller group. The appropriate group for some hinged Archimedean tilings turns out to be . Our symmetry condition can never predict equiauxeticity for this case, as a totally symmetric distortion can have different expansion in orthogonal directions in this symmetry. A totally symmetric mode in could perhaps be made auxetic by careful tuning.

We note that equations such as (3) predict the net mobility ; any mechanisms that are cancelled by equisymmetric states of self-stress are not detectable by this method. Furthermore, if contains the totally symmetric representation, the predicted mechanisms of any symmetry might be infinitesimal in nature. In consequence, a mechanism detected by the symmetry criterion can be guaranteed finite only if it can be shown that there is no totally symmetric state of self-stress in the reduced symmetry corresponding to that mechanism [43].

We use the terminology of equiauxetic modes and frameworks. An equiauxetic mode is a mechanism in which symmetry forces cause uniform expansion of the framework, i.e., a ’breathing’ mode. This mode can either maintain the full symmetry of the framework (when it belongs to the totally symmetric irreducible representation) or it may halve the group [16]. We call a framework an equiauxetic framework only if the mechanism is an equiauxetic mode. Such a system must deform with a Poisson’s ratio of .

3. Single-Link Hinged Tilings

For single-link hinged tilings, the mobility count is given by the trace of (3) under the identity operation, i.e.,

as n counts the bodies (tiles), one bar is associated with each of the b edges in the unit cell, and the characters of sets of in-plane translations and rotations are, respectively, and . In the single-link case, the site symmetry of the hinge constraint is that of an edge in the original tiling, subject to the exclusion of any improper symmetry, and is either or the trivial .

3.1. Calculations

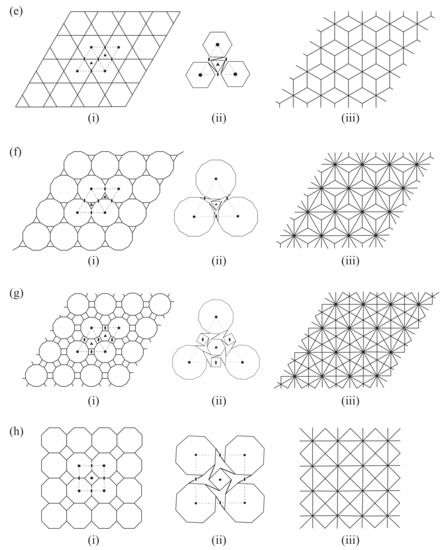

Calculations of the mobility representation using Equation (3) are now shown for the eight single-linked Archimedean tilings. In each case, the calculation is carried out for a array of copies of the basic unit cell indicated in Figure 1. The steps in the calculation are shown in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 for each of the single-link Archimedean tilings. For an explicit example of how characters are calculated, consider Table 2 for tiling . The rhomboidal unit cell, shown below in Figure 2a, contains in total one hexagon and eight triangles. At each corner of the cell, a axis (and hence also and axes) passes through the centre of the unique hexagon h; a axis passes through the centres of triangles and in the interior of the cell, and a two-fold axis passes through edge midpoints , at the centre of the cell, and , at the centres of the cell edges.

Table 2.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1a). The table shows the calculation of the mobility representation . Entries for rotations and their inverses are equal, as permutation representations and are real. Entries under depend on the parity of k.

Table 3.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1b).

Table 4.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1c).

Table 5.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1d).

Table 6.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1e).

Table 7.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1f).

Table 8.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1g).

Table 9.

Character calculation for fragments of single-link hinged tiling (See Figure 1h).

Figure 2.

Odd- and even-multiple unit cells for the tiling: (a) ; (b) .

The face centres of the tiling are vertices of the Laves dual, and edge centres in both the tiling and its dual coincide, so the Laves tiling defines the contact polyhedron C. As noted earlier, reducible representations and are permutation representations in which the entries count the appropriate structural components unshifted within the unit cell (or moved to translationally equivalent sites in neighbouring cells) by the rotations that comprise point group . Equivalently, this counting can be achieved by keeping track of the number of symmetry element symbols that lie within a unit cell (with fractional counting for elements on the cell perimeter). The characters of permutation representations are by definition purely real, even though the separably degenerate irreducible representations of cyclic groups have complex characters.

For this tiling, with odd values of k, the entry in under is 1 (h preserved); under it is 3 (h, , all preserved); under it is 1 (only h preserved, as no other face of the tiling is pierced by a axis). The edge representation has entry 0 for and (an edge in a 2D lattice cannot lie on a axis with ), and the entry for is 3 (, , all preserved). For even values of k, entries under and are unchanged, but the entry under is 4 (, , , preserved); likewise, the entry in is now 0 (as no symmetry element passes through an edge). Characters under the identity are trivially equal to the tile counts of for vertices and for edges of , respectively. Hence, as shown in Table 10, the final result for the reducible representation is a sum of and , i.e., a sum of copies of the regular representation and one copy of the totally symmetric representation: .

Table 10.

Mobility representations for single- and double-link hinged (regular and Archimedean) tilings. The reducible representation of the net mobility, , is listed for a array of copies of the smallest unit cell. Results for the Archimedean tilings follow from Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, and those for the three regular tilings are adapted from [19]. is the regular representation, with entry under the identity, and zero under all other operations: is in ; in ; in ; in .

3.2. Discussion

Table 10 shows interesting systematics for single-link and double-link hinged tilings. In the case of single-link hinges, the mobility representation is strictly positive in that all the single-link hinged tilings have at least one symmetry detectable mechanism, and none have a symmetry-detectable state of self-stress. In four cases, one regular () and three Archimedean (, , and ), there is a unique symmetry-detectable mechanism, which is non-degenerate and in fact totally symmetric. Hence, by the symmetry criterion for equiauxeticity discussed above, all four of these frameworks are detectably equiauxetic, giving us three new single-link cases.

3.3. Finiteness of Mechanisms

Furthermore, we claim that in each case, the detected equiauxetic mechanism extends to a finite motion. The interesting cases are those where the mobility representation is exactly , where is the totally symmetric representation in the point group. In such a case, we can argue that the predicted totally symmetric mechanism is not blocked by an equisymmetric state of self-stress (SOSS) and, hence, is finite and equiauxetic. We can characterise each SOSS by assigning a scalar to every bar to represent the tension in that bar. Proof that the equiauxetic mode is finite follows case by case.

Theorem 1.

Single-link hinged versions of the tilings , , and each give an equiauxetic framework supporting a unique, totally symmetric, finite equiauxetic mode.

Proof.

In each case, we consider a configuration close to the original closed arrangement, as pictured in the central column of Figure 1. ‘Close’ here implies that this configuration occurs before the system reaches any ‘special’ configurations, where, for instance, sets of bars become aligned. If the chosen configuration can be shown not to have a state of self-stress, then the infinitesimal mechanism that is detected must extend to a finite path.

Case 1.

Consider the single-link tiling in Table 7. If there were equal tensions in all bars connecting to a triangular tile, that tile would not be in equilibrium until the motion had reached the ‘special’ fully extended configuration with all bars directed radially from the triangle centre. We could assign zero tension to these bars, but that would require zero tension in all bars attached to any neighbouring dodecagonal tile, as this tile has alternating constraints connecting it to triangular and dodecagonal tiles. Therefore, the SOSS would have a zero scalar on every bar and would be the null vector. Thus, the equiauxetic mechanism is finite.

Case 2.

For tiling in Table 8, the argument is similar but slightly more involved. If a hexagonal tile is in equilibrium, then the bars linking this tile to dodecagonal neighbours all have the same sign, and hence the bars linking hexagonal to square tiles have the opposite sign. If the square tiles are in equilibrium, then all bars to the dodecagonal tiles carry the same sign, and hence, those tiles cannot be in equilibrium. Thus, the equiauxetic mechanism is finite.

Case 3.

A similar argument applies to the tiling , in Table 9, established by requiring equilibrium of square and then octagonal tiles. Hence, the motion is finite in this case too.

Case 4.

Of the regular tilings, the hexagonal tiling also has equal to a single copy of the totally symmetric representation. The argument here is simple, in that all bars are equivalent, so if any one bar is in tension, equilibrium is impossible [19]. Hence, all cases (1) to (4) have finite equiauxetic mechanisms. □

In summary, there are four cases where the single-link frameworks have equal to A, implying a single, equiauxetic mode for all choices of unit cells. These are , , , and . The regular was treated in [19]. Here, we have identified three more equiauxetic frameworks by extending symmetry counting calculations to single-link hinged Archimedean tilings.

4. Double-Link Hinged Tilings

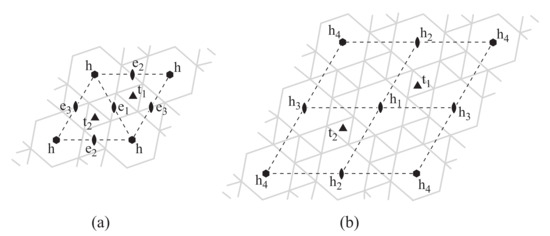

We also consider here the double-link analogue of the hinged structures discussed above. These have been described before for regular tilings [19], and an example of the construction for doubling up on the number of links is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Single-link (a) and double-link (b) versions of the hinged tilings. A sample of the auxetic expansion mode for , the Kagome lattice, is shown here. A similar construction can be applied to any of the systems illustrated in Figure 1. The extra constraint imposed by the double link made up of bars of the same length implies that the edges of linked tiles remain pairwise parallel, as in the unexpanded system.

For double-link hinged tilings, the mobility count is again given by the trace of Equation (3) under the identity,

as and in 2D, and n counts the bodies (tiles) as before, but now two bars are associated with each of the b edges in the unit cell. In the double-link case, the site symmetry of any individual bar constraint is the trivial .

Calculations and Discussion

The mobility calculation for the double-link version of a hinged tiling is identical to that for the single-link in all but one respect. There are now two constraints per edge of the original tiling, and there is no symmetry element preserving a constraint. The permutation representation now has equal to twice the value for the single-link version, but zero under all other operations, i.e., it is a multiple of . Hence, is available by a simple modification of the tabulated character calculations for the single-link case.

The results for the modified calculation have already been given in the final column of Table 10. For the single-link hinge tilings, many cases have mechanisms in addition to the totally symmetric expansion that is present in all cases. The double-link version is overconstrained according to the scalar count in almost all cases. (The exceptions are the zero counts for and with ). In the symmetry counts, the same overconstraint is shown in the reducible representation for general values of k, which typically includes a positive multiple of the totally symmetric representation A balanced against a negative multiple of the regular representation proportional either to or . Hence, the totally symmetric representation A appears in with zero or negative weight in most cases. The exceptions, where the sole symmetry-detectable mechanism is of A symmetry, are the four double-link hinged frameworks with based on , , , and . The regular case was treated in [19]. Here, we have identified three more equiauxetic frameworks by extending symmetry counting calculations to the double-link hinged Archimedean tilings.

We can show that the equiauxetic modes in these cases are finite mechanisms.

Theorem 2.

Double-link hinged versions of the tilings , , and (all with ) each give an equiauxetic framework supporting a unique, totally symmetric, finite equiauxetic mode.

Proof.

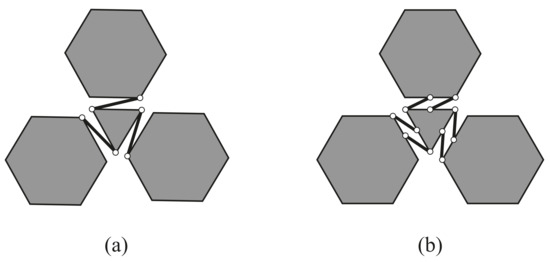

We start by establishing two symmetry conditions. Condition (1): Consider an n-gon of the tiling that has an n-fold axis of symmetry through its centre. For such a polygon, all n edge pairs must have the same member forces and (call this, for simplicity, a type-1 n-gon). For a type-1 polygon, n rotated copies of , and can only give equilibrium if each resultant of and passes through the centre of the n-gon. (This is always possible for some values of and if the two links are not collinear.). Since and are parallel, their resultant is also parallel with them. Near to the initial configuration, however, the resultant cannot pass through the centre of the other (connected) polygon. Condition (2): Any pair of links on a -element enforces , and runs along the midline of and .

Now we look at the tilings case by case.

Case 1.

: Condition (2) forces each to be parallel with its pair of links and not passing through the centres of connected hexagons, 6-fold symmetry implies six resultant forces representing the same moment about the centre of the hexagon, and hence, equilibrium is not possible with non-zero forces in links in this case.

Case 2.

: Both the hexagons and triangles are of type 1, so any resultant should be directed through the centres of the connected hexagon and triangle, which is not possible in a general configuration near to the initial closed configuration.

Case 3.

: Consider the double-link analogue of Figure 1a(ii). Since both the hexagon and the central triangle (with a axis in its centre) are of type 1, the resultant of forces around the hexagon (call it ) and any non-zero resultant of forces around the central triangle (call this ) must go through their respective face centres. Now, any non-central triangle must be balanced by a copy of and , as well as by the third resultant S represented by the pair on a axis. Close to the initial state, however, it is impossible for these to be concurrent since the intersection of and is outside the triangle, just beyond its vertex in front of the axis, while S passes that axis and is nearly parallel to the edges on which S acts. Hence, equilibrium is not possible with non-zero forces in links in this case.

Case 4.

: Consider the double-link analogue of Figure 1c(ii). Since squares are of type 1, all resultants of are equal and pass through the centres of their respective faces. Now, close to the initial configuration, any pair of triangles sharing a axis is surrounded by four copies of that have a moment with the same sense about the shared axis. Hence, equilibrium is not possible with non-zero forces in links in this case. □

An animation of the equiauxetic mode for the double-link hinged Kagome framework () is available as file S1 Kagome.mp4 in the Supplementary Material for this article.

5. Conclusions

The analysis reported here has illustrated the power of applying symmetry to the mobility criteria for periodic frameworks. The extension from pure counting to counting-with-symmetry typically leads to stronger necessary conditions for motion. Here, we have shown that the extended count given by the master equation for periodic body-bar frameworks (3), combined with the criterion for equiauxeticity from Section 2.2, allows us to detect generic equiauxetic behaviour in plausible models of 2D materials and metamaterials based on the canonical Archimedean tilings of the plane.

The main result of this analysis is the identification of two new sets of equiauxetic 2D frameworks, one set emerging from tilings with single links and the other from tilings with double links.

For single-link frameworks of the type shown in Figure 1, scalar counting shows that all are underconstrained. The symmetry-extended calculation shows that every framework has at least one totally symmetric, equiauxetic mode, and it detects no states of self-stress. Exactly four of the regular and Archimedean tilings generate equiauxetic single-link frameworks. These are , , and , and the previously identified [19] regular hexagonal case .

In contrast, double-link frameworks of the type shown in Figure 3b are typically overconstrained, as the scalar counts for show for all but , and . The application of symmetry reveals that these counts mask the existence of a totally symmetric equiauxetic mode for , for all but and . In four cases, the only mechanism detected by symmetry is the totally symmetric equiauxetic mode, and hence these are equiauxetic frameworks. These are , , , and the previously identified [19] regular hexagonal case .

Counting arguments for mobility lead to necessary rather than sufficient conditions as they relate to a difference, not an absolute value. This is true of scalar counting and is still true of counting with symmetry. Addition of an equal number of mechanisms and states of self-stress does not change , and addition of equisymmetric sets of mechanisms and states of self-stress (i.e., sets that transform in the same way under all symmetry operations of the framework) does not affect . In this connection, an interesting observation from the calculations reported here concerns the single-link hinged tilings and . The same scalar count of independently of k holds for both because the triangles in the interstices between the 12-gons add to the count of freedoms, but this is cancelled by the constraints imposed by the bars that connect to the triangles. In the character table calculation of the symmetry , the scalar count implies that the character under the identity operation is the same for the single-link hinged tilings and . The triangles of lie on axes, and hence the has character 3 under the associated operations, but this does not contribute to as the character of the rigid body modes is zero for this operation. In effect, the contact polyhedron for can be reduced to that of and by removing the vertices and edges associated with the triangles without affecting . The missing tiles can be reinstated with an appropriate rotation for any configuration of the framework.

Although the examples in Figure 1 refer to equilateral tiles, the symmetry calculations would be the same for a wider class of systems. For example, subject to retention of symmetry, edge lengths might be modified or gaps might be introduced between tiles, and indeed, the precise geometry of the single and double links has not been specified here beyond the restrictions imposed by symmetry.

It is also interesting to compare the present study with results on the mobility of tilings constructed under different physical models. In [7,16,18], Archimedean tilings are included amongst examples of bar-and-joint frameworks defined in a different way by considering the edges of the tiles as a bar-joint network rather than considering the tiles as rigid-bodies—that model also generates equiauxetic frameworks of a different kind.

Other directions for future work suggested by the present investigation include physical modelling of the systems studied here and extension of the symmetry techniques to 3D. Reproduction of pin-jointed frameworks with 3D printing techniques is problematic, but by introducing elasticity and replacing the pin joints with ‘elastic joints’, it should be possible to study the resulting compliant mechanisms in physical models produced by this technology. Extension of our symmetry reasoning to the design of auxetics and equiauxetics in 3D is also a compelling future direction for this research area. We believe that the symmetry approach has much to offer in terms of generating ideas for new metamaterials and in analysing the performance of systems of this type.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sym14020232/s1 One animation file (Video S1 Kagome.mp4) is available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; methodology, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; validation, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; visualization, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; formal analysis, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; investigation, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K.; writing—review and editing, T.T., P.W.F., S.D.G. and F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NKFIH under grants K 119440 (T.T. and F.K.), K 128584 (F.K.) and TPK2020 BME-NCS (F.K.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ren, X.; Das, R.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Xie, Y.M. Auxetic metamaterials and structures: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, Z.-M.; Shi, W.; Xie, B.-H.; Yang, M.-B. Review on auxetic materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 3269–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.E.; Alderson, A. Auxetic Materials: Functional Materials and Structures from Lateral Thinking! Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R.S. Negative-Poisson’s-Ratio Materials: Auxetic Solids. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2017, 47, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T. Auxetic Materials and Structures; Engineering Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y. Auxetic Textiles; The Textile Institute Book Series; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mitschke, H.; Robins, V.; Mecke, K.; Schröder-Turk, G.E. Finite auxetic deformations of plane tessellations. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 469, 20120465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borcea, C.S.; Streinu, I. Periodic frameworks and flexibility. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 466, 2633–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R.S. Foam Structures with a Negative Poisson’s Ratio. Science 1987, 235, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.E. Auxetic polymers: A new range of materials. Endeavour 1991, 15, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, J.N.; Evans, K.E. Auxetic behaviour from rotating squares. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 19, 1563–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Grima, J.N.; Alderson, A.E.; Evans, K.E. Auxetic behaviour from rotating rigid units. Phys. Status Solidi 2005, 242, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, D.; Grima, J.N. Auxetic behaviour from rotating rhombi. Phys. Status Solidi 2008, 245, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, L.; Azzopardi, K.M.; Attard, D.; Grima, J.N.; Gatt, R. Auxetic metamaterials exhibiting giant negative Poisson’s ratios. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL)—Rapid Res. Lett. 2015, 9, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, L.; Azzopardi, K.M.; Gatt, R.; Farrugia, P.S.; Grima, J.N. An analytical and finite element study on the mechanical properties of irregular hexachiral honeycomb. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, H.; Schröder-Turk, G.E.; Mecke, K.; Fowler, P.W.; Guest, S.D. Symmetry detection of auxetic behaviour in 2D frameworks. EPL Europhys. Lett. 2013, 102, 66005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guest, S.D.; Fowler, P.W. Symmetry-extended counting rules for periodic frameworks. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014, 372, 20120029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, H. Deformations of Skeletal Structures. Master’s Thesis, Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, P.W.; Guest, S.D.; Tarnai, T. Symmetry Perspectives on Some Auxetic Body-Bar Frameworks. Symmetry 2014, 6, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Jiang, D.; Schedin, F.; Booth, T.J.; Khotkevich, V.V.; Morozov, S.V.; Geim, A.K. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10451–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, X.; Kawazoe, Y.; Jena, P. Penta-graphene: A new carbon allotrope. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2372–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Einollahzadeh, H.; Fazeli, S.M.; Dariani, R.S. Studying the electronic and phononic structure of penta-graphene. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2016, 17, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, Q.; Xing, D.; Sun, J. Superconducting Single-Layer T-Graphene and Novel Synthesis Routes. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2019, 36, 097401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, Y.; Cardone, G.; Restrepo, D.; Zavattieri, P.D.; Baker, T.S.; Tezcan, F.A. Self-assembly of coherently dynamic, auxetic, two-dimensional protein crystals. Nature 2016, 533, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, A. Hinged Tilings. N. Am. GeoGebra J. 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Attard, D.; Farrugia, P.S.; Gatt, R.; Grima, J.N. Starchirals: A novel class of auxetic hierarchal structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 179, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, F.A.; Favata, A.; Micheletti, A.; Paroni, R. Design of auxetic plates with only one degree of freedom. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2021, 42, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, L.; Spaggiari, A. Chiralisation of Euclidean polygonal tessellations for the design of new auxetic metamaterials. Mech. Mater. 2021, 153, 103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünbaum, B.; Shephard, G.C. Tilings and Patterns; Dover Books on Mathematics Series; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, F.; Tarnai, T.; Fowler, P.W.; Guest, S.D. A class of expandable polyhedral structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2004, 41, 1119–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, F.; Tarnai, T.; Guest, S.D.; Fowler, P.W. Double-link expandohedra: A mechanical model for expansion of a virus. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2004, 460, 3191–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speir, J.A.; Munshi, S.; Wang, G.; Baker, T.S.; Johnson, J.E. Structures of the native and swollen forms of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus determined by X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. Structure 1995, 3, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Sheng, J.; Plevka, P.; Kuhn, R.J.; Diamond, M.S.; Rossmann, M.G. Dengue structure differs at the temperatures of its human and mosquito hosts. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6795–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tay, T.-S. Rigidity of multi-graphs. I. Linking rigid bodies in n-space. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 1984, 36, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guest, S.; Schulze, B.; Whiteley, W.J. When is a symmetric body-bar structure isostatic? Int. J. Solids Struct. 2010, 47, 2745–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guest, S.D.; Fowler, P.W. A symmetry-extended mobility rule. Mech. Mach. Theory 2005, 40, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatov, V.A.; O’Keeffe, M.; Proserpio, D.M. Vertex-, face-, point-, Schläfli-, and Delaney-symbols in nets, polyhedra and tilings: Recommended terminology. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coxeter, H. Regular Polytopes; Dover Books on Advanced Mathematics; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, P.W.; Child, M.S.; Phillips, C.S.G. Tables for Group Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, S.L.; Herzig, P. Point-Group Theory Tables; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D.M. Group Theory and Chemistry; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, P.W.; Guest, S.D. A symmetry extension of Maxwell’s rule for rigidity of frames. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2000, 37, 1793–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangwai, R.; Guest, S. Detection of finite mechanisms in symmetric structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1999, 36, 5507–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).