1. Introduction

For the unconstrained optimization problem

Cartis et al. [

1] proposed an adaptive cubic regularization (ACR) algorithm. It is an alternative to classical globalization techniques, which uses a cubic over-estimator of the objective function as a regularization technique, and uses an adaptive parameter

to replace the Lipschitz constant in the cubic Taylor-series model. At each iteration, the objective function is approximated by a cubic function. Numerical experiments in [

1] show that the ACR is comparable with trust-region method for small-scale problems. Despite the fact that the method has been shown to have powerful local and global convergence properties, the practicality and efficiency of the adaptive cubic regularization method depend critically on the efficiency of solving its sub-problem at each iteration.

For solving the trust-region sub-problem, many efficient algorithms have been proposed. These algorithms can be grouped into three broad categories: the accurate methods for dense problems, the accurate methods for large-sparse problems, and the approximation methods for large-scale problems. The first category are the accurate methods for dense problems, such as the classical algorithm proposed by Moré and Sorensen [

2], which used Newton’s method to iteratively solve symmetric positive definite linear systems via the Cholesky factorization. The second category are the accurate methods for large-sparse problems. For instance, the Lanczos method was employed to solve the large-scale trust-region sub-problem through a parameterized eigenvalue problem [

3,

4]. Another accurate approach [

5], is based on a parametric eigenvalue problem within a semi-definite framework, which employed the Lanczos method for the smallest eigenvalue as a black box. Hager [

6] and Erway et al. [

7] utilized the subspace projection algorithms for accurate methods. The third category are the approximation methods for large-scale problems. The generalized Lanczos trust-region method (GLTR) [

8,

9] was proposed as an improved Steihaug [

10]-Toint [

11] conjugate-gradient method. For the GLTR method, Zhang et al. established prior upper bounds [

12] and posterior error bounds [

13] for the optimal objective value and the optimal solution between the original trust-region sub-problem and their projected counterparts.

For solving cubic models sub-problems, many algorithms are extensions of trust-region algorithms. Cartis et al. [

1] provided the Newton’s method to solve the sub-problem of ACR, which employs Cholesky factorization at each iteration. This method usually applies to small-scale problems. Moreover, Cartis et al. briefly described the process of using the Lanczos method for the ACR sub-problem in [

1]. Carmon and Duchi [

14] provided the gradient descent method to approximate the cubic-regularized Newton step, and gave the convergence rate. However, the convergence rate of the gradient descent method is worse than that of the Krylov subspace method. Birgin et al. [

15] proposed a Newton-like method for unconstrained optimization, whose sub-problem is similar to but different from that of ACR. They introduced a mixed factorization, which is a cheaper factorization than the Cholesky factorization. Brás et al. [

16] used the Lanczos method efficiently to solve the sub-problems associated with a special type of cubic models, and also embedded the Lanczos method in a large-scale trust-region strategy. Furthermore, an accelerated first-order method for the ACR sub-problem was developed by Jiang et al. [

17].

In this paper, we employ the Lanczos method to solve the sub-problem of the adaptive cubic regularization method (ACRL) for large-scale problems. The ACRL algorithm mainly includes the following three steps. Firstly, the ACRL generates the jth Krylov subspace using the Lanczos method. Next, we project the original sub-problem onto the jth Krylov subspace to obtain a smaller-sized sub-problem. Finally, we solve the resulting smaller-sized sub-problem to get an approximate solution. Such procedures are based on the minimization of the local model of the objective function over a sequence of small-sized sub-spaces. As a result, the ACRL is applicable for large-scale problems. Moreover, we analyze the error of the Lanczos approximation. For unconstrained optimization problems, we perform numerical experiments and compare our method with the method of not using the Lanczos approximation (ACRN).

The outline of this paper is as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce the adaptive cubic regularization method and its optimality condition. The method using the Lanczos algorithm to solve the ACR sub-problem is introduced in

Section 3. In

Section 4, we show the error bounds of the approximate solution and approximate objective value obtained using the ACRL method. Numerical experiments demonstrating the efficiency of the algorithm are given in

Section 5. Finally, we give some concluding remarks in

Section 6.

2. Preliminaries

Throughout the paper, a matrix is represented by a capital letter, while a lower case bold letter is used for a vector and a lower case letter for a scalar.

The adaptive cubic regularization method [

1,

18] is proposed by Cartis et al. for unconstrained optimization problems. It mainly uses a cubic over-estimator of the objective function as a regularization technique to calculate the step at each iteration. Assuming that

is the current iteration point, the objective function

is second-order continuously differentiable, and its Hessian matrix

is globally Lipschitz continuous. For any

, by expressing the Taylor expansion of

at the point

, we obtain

where

,

, and

L is the Lipschitz constant. Here, and for the remainder of this paper,

denotes an

norm. The inequality is obtained by using the Lipschitz property of

. In [

1], Cartis et al. proposed to replace the constant

in Equation (

1) with a dynamic positive parameter

. In the cubic regularization model, the matrix

needs not to be globally or locally continuous in general. Furthermore, the approximation of

by a symmetric matrix

is employed at each iteration. Therefore, the model

is used to estimate

at each iteration. Then, the adaptive cubic regularization method sub-problem aims to compute a descent direction vector

. Finally, the sub-problem is given with the form of

in which

is short for

Cartis et al. introduced the following global optimality result of ACR, which is similar to the optimality conditions of the trust-region method.

Theorem 1 ([

1], Theorem 3.1).

The vector is a global minimizer of the sub-problem (3) if and only if there is a scalar satisfying the following system of equations:where , and is a positive semi-definite matrix. If is positive definite, then is unique. The optimality condition of the trust-region sub-problem [

19] aims to minimize

within an

-norm trust region

, where

is the trust-region radius. For a trust-region sub-problem, the vector

satisfies

, which means either

. When both the trust-region sub-problem and the cubic regularization sub-problem approximate the original objective function precisely enough, we get

from Theorem 1. Therefore, the parameter

in the ACR algorithm is inversely proportional to the trust-region radius, and it plays the same role as the trust region-radius, while we adjust the estimation accuracy of the sub-problem.

3. Computation of the ACR Sub-Problem with the Lanczos Method

The Lanczos algorithm [

20] was proposed to solve sparse linear systems and to find the eigenvalues of sparse matrices. It builds up an orthogonal basis

for the Krylov space

By utilizing the orthogonal basis

the original symmetric matrix

B is transformed into a tridiagonal matrix.

Normally, the dimension of the increases by 1 as j increases by 1. However, the Lanczos process may break down and the dimension of stops increasing at a certain j. We define as the smallest nonnegative integer, such that the Lanczos process breaks down. If the dimension of the Krylov space is much less than the size of the matrix, it greatly saves the storage space and highly improves the calculation speed by projecting B onto a subspace. Specially, we find a proper using the Lanczos method, such that is tridiagonal. We state the procedure in the following algorithm.

Algorithm 1 computes an orthogonal matrix

, where

is tridiagonal. Moreover, it follows directly from Algorithm 1 that

where

is the first unit vector of

in length.

| Algorithm 1 Lanczos algorithm |

- 1:

- 2:

while

or

do - 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

end while

|

For a large-scale trust-region sub-problem, an effective solution is to approximately calculate it using the Krylov subspace methods. The Lanczos algorithm, as one of the Kryolv subspace methods, was first introduced in [

8] for the trust-region method. Similar to the trust-region method, the Lanczos algorithm is also suitable for solving the cubic regularization sub-problem. By employing Algorithm 1, we find

where

is defined by (

3). The original sub-problem (

3) is transformed into the following sub-problem

Theorem 1 illustrates that

is a global minimizer of the above sub-problem, if and only if a pair of

satisfies

where

is positive semi-definite. Equation (

8) can finally be solved by Newton’s method ([

1], Algorithm 6.1). Newton’s method for solving the sub-problem requires the eigenvalue decomposition of

for various

. When the scale of the original problem is large, it is very expensive to directly use the iterative method.

In summary, an approximation

of the solution of the ACR sub-problem (

3) can be obtained in the following steps. First, we apply

j steps of the Lanczos method to the cubic function appearing in (

3) to obtain a tridiagonal matrix

. Then, we use the Newton’s method for a small-size sub-problem with matrix

to compute the Lagrange multiplier

and

. Finally, the matrix

is used to recover

. Thus, it should be noted that the Lanczos vectors need to be saved. We sketch the algorithm as follows.

In the GLTR algorithm, ([

8], Theorem 5.8) discussed a restarting strategy for the degenerate case, which means that multiple global solutions

exist. Similar to the GLTR, a restarting strategy also applies to the ACRL, although this is just discussed from a theoretical perspective. Therefore, we mainly consider the nondegenerate case in the following analysis.

5. Numerical Experiments

In order to show the efficiency of the Lanczos for improving the adaptive cubic regularization algorithm, we perform the following two numerical experiments. In this section, we compare the numerical performances of the adaptive cubic regularization algorithm when using the Lanczos approximation method (ACRL) and the adaptive cubic regularization algorithm by just using Newton’s method (ACRN) for unconstrained optimization problems.

The ACRL and ACRN algorithms are implemented with the following parameters

Convergence in both algorithms for the sub-problem occurs as soon as

or if more than the maximum number of iterations has been performed, which we set to 2000. All numerical experiments in this paper were performed on a laptop with i5-10210U CPU at 1.60 GHz and 16.0 GB of RAM.

Example 1 (Generalized Rosenbrock function [

21]).

The Generalized Rosenbrock function is a non-convex function, introduced by Howard H. Rosenbrock in 1960, which is defined as follows: From the (

23), the solution

is obviously

, and the minimum

.

In

Table 1, we show the results of the ACRL and the ACRN for computing the minima of the Generalized Rosenbrock function, with variables from 10 to 2000. In addition to the dimensions of the Generalized Rosenbrock function, we give the number of iterations (“Iter.”), the total CPU time required in seconds and the relative error between the computational result and the exact minimum (“Err.”). It can be seen that, using the Lanczos method to solve the adaptive cubic regularization sub-problem of Generalized Rosenbrock function is much more efficient than not using the Lanczos method. Moreover, it is not only faster, but also more accurate to calculate, especially when the scale is relatively large.

Example 2 (Eigenvalues of tensors arising from hypergraphs).

Next, we consider the problem of computing extreme eigenvalues of sparse tensors arising from a hypergraph. An adaptive cubic regularization method on a Stiefel manifold named ACRCET is proposed to solve the eigenvalues of tensors [22]. We compare the numerical performances of the ACRL and the ACRN method when applying to the sub-problem of ACRCET. Before going to the experiment part, we first introduce the concepts of tensor eigenvalues and hypergraphs. A real

mth order

n-dimensional tensor

has

entries:

for

If the value of

is invariable under any permutation of its indices,

is a symmetric tensor.

Qi [

23] defined a scalar

as a Z-eigenvalue of

and a nonzero vector

as its associated Z-eigenvector if they satisfy

Definition 1 (Hypergraph). A hypergraph is defined as , where is the vertex set and is the edge set for If for and when , we call G an r-uniform hypergraph.

For each vertex

, the degree

is defined as

Definition 2 (adjacency tensor and Laplacian tensor).

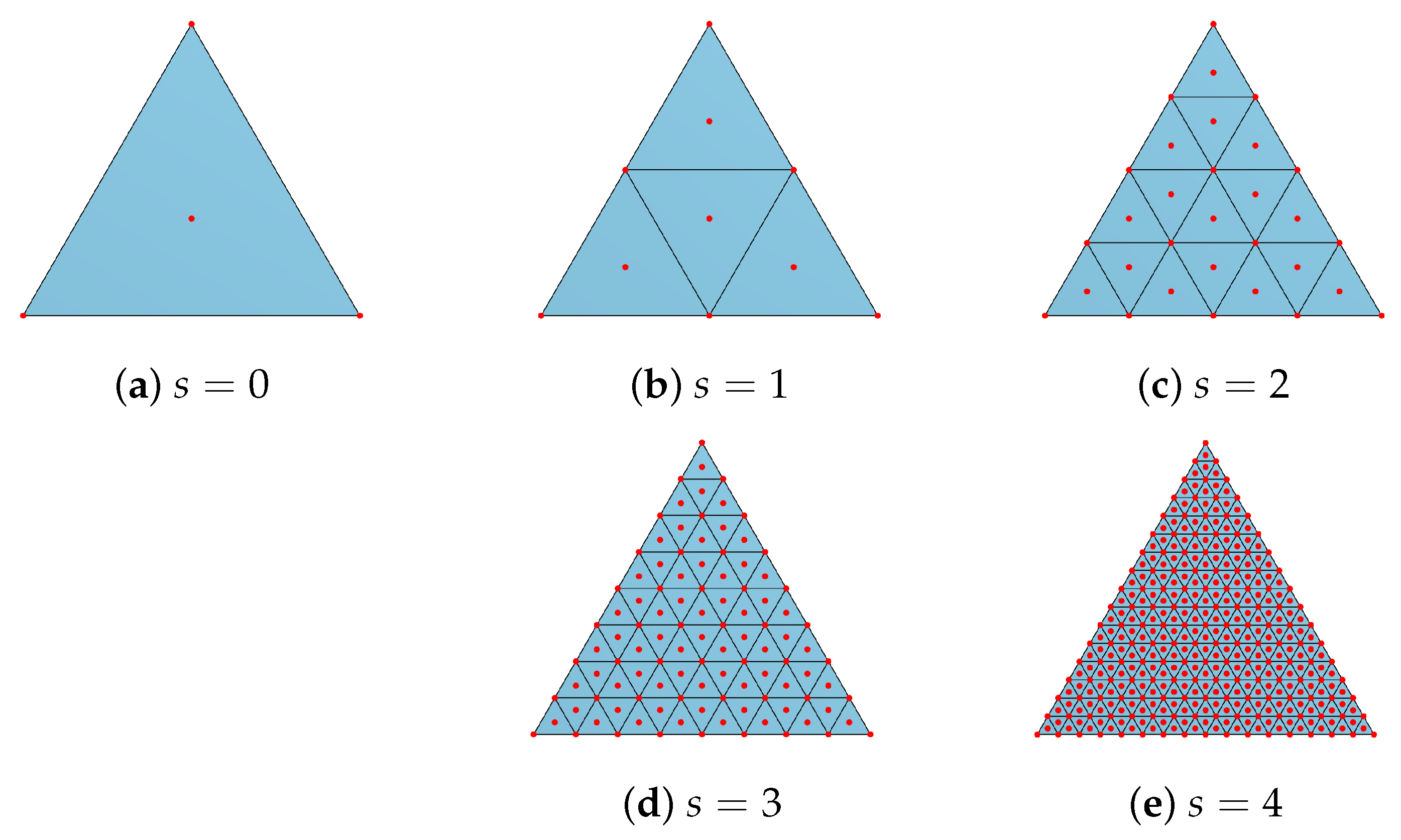

The adjacency tensor of a m-uniform hypergraph G is a symmetric tensor with entriesFor an m-uniform hypergraph G, the degree tensor is a diagonal tensor whose ith diagonal element is . Then, the Laplacian tensor is defined as A triangle has three vertices and three edges. In this example, we subdivide the triangles by connecting the midpoints of each edge of the triangles. Then, the

s-order subdivision of a triangle has

faces, and each face is a triangle. As shown in

Figure 1, three vertices as well as the center of the triangles are regarded as an edge of a 4-uniform graph

.

We compute the largest Z-eigenvalue of the Laplacian tensor

via the ACRCET method, using ACRL and ACRN, respectively. In each run, 10 points on the unit sphere are randomly chosen, and 10 estimated eigenvalues are calculated. Then, we take the best one as the estimated largest eigenvalue. For different subdivision order

the computation results, including the estimated largest Z-eigenvalue, the total number of iterations, and the total CPU time (in seconds) of the 10 runs are reported in

Table 2.

It can be seen that both the ACRL and the ACRN find all the largest eigenvalues. However, the ACRL takes almost no time compared to the ACRN. When

, the ACRL method only costs 236 s, while the ACRN needs 103,900 s. The numerical comparison between the ACRL and the ACRN verifies that the Lanczos method dramatically accelerates the running speed when solving the ACR sub-problem (

3), and is powerful for large-scale problems.