Abstract

Diversification is a strategy adopted by many enterprises in the process of expansion. The success of the diversification of an enterprise mainly depends on the choice and implement of strategy; choosing an organizational structure that fits the type of diversification strategy used is fundamental to improving financial performance. Based on the empirical research method, this study establishes a symmetric model of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance and selects data from 613 A-share-listed companies in China, from 2012 to 2016, to test the impacts of unrelated and related diversification strategies on financial performance, as well as the moderating effects of united company, holding company, and multidivisional structures on such relationships. The results show that there is asymmetry between the diversification strategy adopted and financial performance, and a related diversification strategy should be adopted as a priority; the symmetry of an unrelated diversification strategy and holding company structure on financial performance is partially confirmed, and other elements should be adopted, simultaneously, to improve this symmetry; a related diversification strategy and multidivisional structure on financial performance is symmetric. The above findings will provide references for the diversification strategy choice and the organizational structure design of enterprises.

1. Introduction

Enterprise management is a large area composed of different elements, and the symmetry of different elements generally exists in enterprise management. Numerous studies have shown that the symmetry of different elements of enterprise management plays a synergistic role in promoting enterprise development [1,2,3]. This idea is also applicable to the diversification strategies of enterprises. Diversification is a strategic business model in which enterprises engage in two or more business areas simultaneously in their process of development [4]. With the gradual growth of scale and capital accumulated, numerous enterprises try to diversify their operations to achieve further expansion. The study based on developed countries indicated that most large enterprises’ development evolved from single or diversified operations [5]. The maximization of financial performance is the common pursuit of diversified enterprise and is also an important indicator with which to measure the success of diversification strategies. The financial performance of a diversified enterprise mainly depends on the choice of strategy used and how strategy is implemented [5,6]. The choice of diversification strategy types directly determines the mode of resource allocation and business operation; choosing different types of diversification strategies may lead to different financial performances [7]. After the diversification strategy is selected, the successful implementation of the diversification strategy requires the synergistic effect of different management elements, among which choosing an organizational structure that is symmetric to the type of diversification strategy used is key to ensuring the realization of financial performance objectives [5,6]. Organizational structure, as the carrier of strategy implementation, directly determines the division of power and responsibility and the design of the management process, and affects the operational efficiency of an enterprise [8]. Numerous enterprises use the same strategy, yet their results differ. An important factor in success is whether the organizational structure can support the implementation of the diversification strategy. Symmetry between the diversification strategy adopted and the organizational structure can promote financial performance. On the contrary, asymmetry between these elements may damage financial performance. Therefore, when facing the complex and evolving market environment, enterprises should treat their diversification strategy rationally, choose an appropriate diversification strategy type, and establish an organizational structure matching their diversification strategy to promote financial performance. Empirically, the symmetric modeling of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance seems to be indispensable.

After the reform and opening up of 1978, Chinese enterprises began to adopt diversification strategies. The Chinese market was further opened after joining the World Trade Organization (WTO). Numerous foreign enterprise groups entered the Chinese market, resulting in many successful cases of diversification. Although Chinese enterprises have been implementing diversification strategies for over 40 years, they remain at the exploratory stage in general [9]. With the emergence of cases of failed diversification, such as Lenovo, Giant, LeTV, and other large enterprise groups, numerous cases of the improper selection of diversification strategy types and the incorrect symmetry of organizational structure and diversification strategy have occurred. These miscalculations lead to certain deviations in the understanding of the diversification strategies of Chinese enterprises [10,11]. Under the current Chinese institutional environment, which diversification strategy is most appropriate? Which organizational structures match the different types of diversification strategy? Therefore, in response to these concerns, studying the diversification strategy choice and organizational structure design of Chinese diversified enterprises has practical significance.

The first contribution of this study is to prove the effectiveness of the economies-of-scope theory in Chinese diversified enterprises. According to the economies-of-scope theory [12], enterprises with a related diversification strategy can realize scope economy better than those with an unrelated diversification strategy; this view has been confirmed by relevant scholars, based on data from other countries [7,13]. This study tested the impacts of unrelated and related diversification strategies on the financial performance using the data of Chinese enterprises. Although there is asymmetry between the diversification strategy adopted and a firm’s financial performance, compared with using an unrelated diversification strategy, the use of a related diversification strategy has a more positive impact on its financial performance. This finding may provide a theoretical basis for enterprises to prioritize related diversification strategies.

The second contribution of this study is to further enrich the structure-following-strategy theory. According to the structure-following-strategy theory, a multidivisional structure match a total diversification strategy [14], but the question of which organizational structures match unrelated and related diversification strategies is still worth exploring. This study tested, separately, the moderating effects of using a united company, holding company, and multidivisional structure on the relationships between unrelated and related diversification strategies and financial performance. The results show that a holding company structure can more positively regulate the impact of using an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance than united and multidivisional structures can, and a multidivisional structure can more positively regulate the impact of using a related diversification strategy on financial performance than united and holding company structures can. These findings may provide a more specific reference to design organizational structures matching unrelated and related diversification strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Diversification Strategy and Financial Performance

In the process of enterprise expansion, it is necessary to first solve the problem of strategic choice. Since the concept of diversification strategy was put forward [4], diversification strategies have been widely adopted by more and more enterprises. While expanding their scale through a diversification strategy, some recent studies show that enterprises should also pay attention to sustainable development through a green investment strategy [15,16]. However, no matter which strategy is used, financial performance has been always one of the most important objectives for enterprises.

The relationship between the diversification strategy used and financial performance has attracted the attention of many scholars. Because samples from many different countries and industries have been used to study the impact of diversification strategy on financial performance, presently no consistent conclusion exists in the academic literature [5,17,18]. The same is true of China. Based on China’s environment, numerous scholars have paid attention to the relationships between diversification strategy and financial performance. However, owing to the different samples used by scholars, a consistent conclusion still remains to be found [9,10,11,19,20].

Some scholars have also studied the relationships between the use of different types of diversification strategy and financial performance. Diversification strategies are divided into unrelated and related diversification strategies [7], and the analyzed results indicate that the financial performance of enterprises with related diversification strategies is better than that of enterprises with unrelated diversification strategies [7,13]. However, this view has been confirmed by numerous scholars using data from other countries, and not from China. This study further explored the impacts of the use of different types of diversification strategy on firms’ financial performances in China—that is, how to choose the type of diversification strategy for Chinese enterprises.

2.2. Diversification Strategy, Organizational Structure, and Financial Performance

In-depth research has found that introducing other variables is necessary when analyzing the impact of the use of a diversification strategy on financial performance [21,22]. In particular, organizational structure, as an important moderator variable affecting the relationship between diversification strategy and financial performance, has attracted some scholars’ attention [6,7] regarding the issue of how to design an organizational structure that matches the diversification strategy used.

Chandler (1962) proposed the structure-follows-strategy theory [14]. Business strategies determine the design of organizational structure modes. Conversely, the implementation process and effect of business strategy are restricted by the organizational structure modes adopted. Further research has proven that strategy is a more important determinant of structure than structure is of strategy [23]. Only with an organizational structure that is adjusted based on the enterprise’s strategy can an enterprise achieve substantial financial performance. Chandler (1962) divided the development stages of enterprises into four stages, namely quantity expansion, regional diffusion, vertical integration, and diversification. When expanding to the fourth stage and implementing a diversification strategy, enterprises can adopt a multidivisional structure, to carry out moderate decentralization management [14]. Following the findings of Chandler, relevant studies support the view that a multidivisional structure matches a diversification strategy [24]. However, this conclusion is based on the premise that a multidivisional structure is suitable for a total diversification strategy, without classifying the actual diversification strategy used.

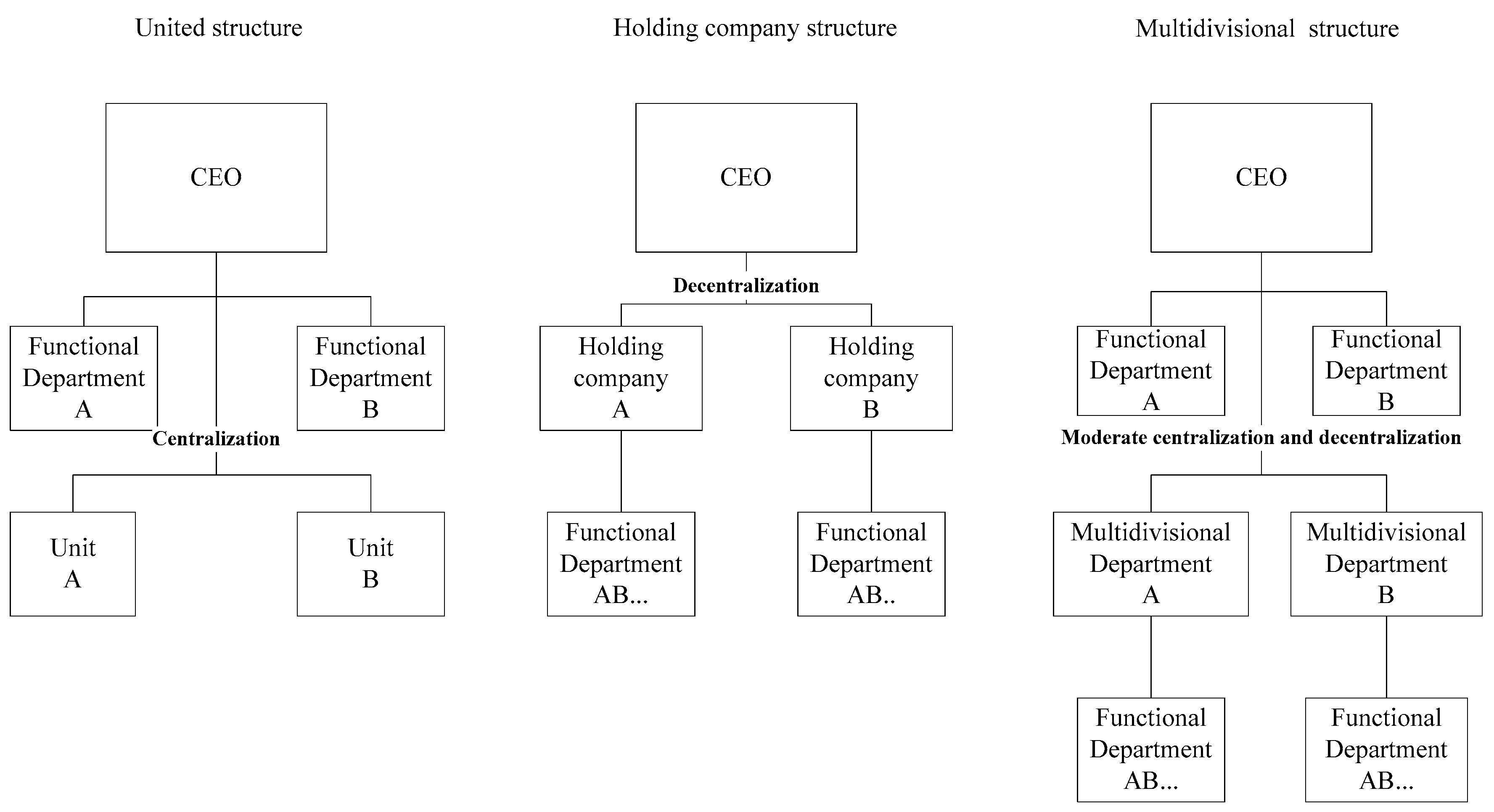

Williamson (1975) divided the types of organizational structure into united, holding company, and multidivisional structures [8]. The united, holding company, and multidivisional structures are shown in Figure 1. The united structure, as a centralized structure, is the most basic form of enterprise organizational structure. The holding company structure, as a decentralized structure, is a model of parent–subsidiary companies with multiple corporate entities. The multidivisional structure is a decentralized management system with high-level centralization, which creates the possibility of giving full play to the advantages of an organization and forward backward integration.

Figure 1.

United, holding company, and multidivisional structures.

In reality, the organizational structure of a diversified enterprise is characterized by diversity, united, holding company, and multidivisional organizational structures; these structures are adopted by numerous enterprises. However, when scholars study the impact of different types of diversification strategy on financial performance, taking organizational structure as a moderator is very rare. Whether these organizational structures can match unrelated and related diversification strategies and improve the financial performances of enterprises remains unknown. The question of how to choose a symmetric organizational structure when implementing different types of diversification strategy needs to be explored in research. Therefore, based on previous studies, this study focuses on the symmetry of the effect of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance, that is, united, holding company, and multidivisional structures are taken as moderator variables that affect the impacts of unrelated and related diversification strategies on financial performance.

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. The Asymmetry of Diversification Strategy on Financial Performance

3.1.1. Theoretical Basis

The economies-of-scope theory describes the economy of multi-product manufacturing enterprises [12]. Specifically, economies of scope exist when two or more product lines are jointly produced in one enterprise rather than separately distributed among different enterprises that produce only one product. The economies-of-scope theory reveals the phenomenon of the cost saving of enterprises engaged in multi-product production. Usually, economies of scope mainly originate from the full use of shared factors. Once such shared factors are invested in the production of a product, they can be used to produce other products in part or in whole without too much cost.

3.1.2. Hypothesis Analysis

Diversification is a business strategy chosen by the enterprise, and its successful implementation depends on the symmetry between the diversification strategy and other internal management elements. Financial performance may not be stable and excellent in a company with a high degree of diversification, a fact which has been confirmed by relevant studies [25,26,27,28]. This indicates that the use of a diversification strategy cannot significantly and positively affect financial performance. Therefore, there is asymmetry between diversification strategy and financial performance. However, this is not to say that an enterprise cannot adopt a diversification strategy; rather, it is necessary and feasible to compare the impacts of unrelated and related diversification strategies on financial performance, to provide a theoretical basis for the choice of diversification strategy for an enterprise.

The economies-of-scope theory can be used to explain why enterprises should give priority to related diversification strategies [29]. With the implementation of a related diversification strategy, synergistic roles can be played in technology, operation, sales, and management of new businesses. A related diversification strategy can reduce the cost of synergy and the business risks, utilize resource and activity sharing at the business level, and benefit from the transmission of core competitiveness at the company level. With the implementation of an unrelated diversification strategy, new businesses have minimal or no connection with the main business. The advantages of using an unrelated diversification strategy is that it can expand the business field, seize external market opportunities, and expand the source of profits. However, unrelated diversification is difficult and risky to implement cross-industry, and the management cost is high, which may lead to the loss of the main business advantages and the erosion of the main business through side businesses. As a result, enterprise resource misallocation may occur and production costs may increase. Therefore, making use of the economies-of-scope theory for unrelated diversification strategies is difficult, leading to an uneconomic scope and ultimately reducing the financial performance of enterprises.

Referring to previous studies based on other countries [7,13], this study assumes that the economies-of-scope theory has universal global significance and that the financial performances of Chinese diversified enterprises conform to the economies-of-scope theory; that is, compared with the use of an unrelated diversification strategy, the production of economies of scope and the improvement of financial performance is easier to achieve through the adoption of a related diversification strategy.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is put forward:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is asymmetry between the diversification strategy used and financial performance, but a related diversification strategy has a more positive impact on financial performance than that of an unrelated diversification strategy.

3.2. The Symmetry of Diversification Strategy and Organizational Structure on Financial Performance

3.2.1. Theoretical Basis

The configural organization theory [30], as a classic theory of organization management, has been adopted and confirmed by multiple studies [31]. According to the configural organization theory, the internal elements of an enterprise are interrelated, coordinated, and form a configuration which becomes a more prominent source of competitive advantage than any single aspect of an enterprise’s strategy. The more the environment changes, the stronger the uncertainty and the looser the organizational structure. By contrast, the less the environment changes, the lower the uncertainty and the more rigid the organizational structure.

3.2.2. Hypotheses Analysis

The configural organization theory can provide a theoretical basis for the organizational structure design of a diversified enterprise. On the basis of the configural organization theory, in combination with the characteristics, advantages, disadvantages, and applications of united, holding company, and multidivisional structures, further analysis can be carried out on the symmetry between united, holding company, and multidivisional structures and unrelated and related diversification strategies.

According to united structure functions, enterprises are divided into different departments. A united structure’s greatest feature is its centralized control at the management level and the horizontal and vertical differentiations of internal management functions, which are convenient for achieving unified and coordinated management. However, its greatest defects are its lack of unified and coordinated management, its lower flexibility, and its poor adaptability to the external environment. Thus, the united structure is suitable for single-strategy enterprises with a low variety of products and a stable external environment. However, a successful diversification strategy must maintain organizational slack management policies [32]. Organizational rigidity increases coordination costs, thus further constraining the economies of scope [33]. A diversification strategy requires enterprises to decentralize and authorize business units to meet the requirements of flexible and efficient operations. The united structure emphasizes centralized control, which is contrary to a diversification strategy. Therefore, regardless of whether enterprises implement an unrelated or related diversification strategy, if the united structure is forcibly adopted, these strategies can have a negative impact on financial performance.

According to holding company structure functions, the relationship between a parent company and a subsidiary company is mainly through property rights. Given that each company, as an independent legal entity, has great independence, the parent company coordinates and controls the goals and actions of the subsidiary company mainly through various committees and functional departments. The control of a parent company over a subsidiary company is generally limited to financial performance assessment and the allocation of funds, whereas the subsidiary company operates with great independence. The holding company structure is highly independent and lacks strategic coordination. Therefore, the holding company structure is difficult to use as a total resource strategy, but it is considerably suitable for enterprises with complex businesses, wide coverage, scattered investment, and low non-correlation. Decentralization improves financial performance by allowing businesses to adapt to the business environment [34]. When enterprises arrangements emphasize competition among business units, companies that attempt to achieve economic benefits from effective internal governance perform well [35]. The implementation of an unrelated diversification strategy in an enterprise that enters the industry with low or no correlation can lead to management complexity issues. Enterprises with unrelated diversification should use the holding company structure, where a parent can function as a group company and a subsidiary can function as a separate legal entity. The corporation controls the subsidiary in terms of strategic, financial, and personnel management, to alleviate the burden on the top management and to ensure that the subsidiary remains flexible to changes in the internal and external environment. At the same time, the holding company structure is not applicable to a related diversification strategy. If an enterprise implements a related diversification strategy and uses the holding company structure, then it will not be conducive to resource sharing and complementary advantages between related and original businesses, and ensuring the synergy of new and old businesses will be difficult.

Compared with the united and holding company structures, the multidivisional structure overcomes the drawbacks of the high centralization of united structure and avoids the shortcomings of the excessive decentralization of the holding company structure. The multidivisional structure allows a full combination of resources and the formation of an appropriate allocation of resources within the enterprise. The integrated mode of the centralization and decentralization of the multidivisional structure is suitable for enterprises with prominent major and relevant businesses. When organizational arrangements emphasize cooperation between business units, companies trying to achieve economies of scope perform well [35]. The multidivisional structure can increase the management ability of related diversified companies for organizational relaxation [36]. Differences in the scope of diversification can be explained by the differences in dynamic capabilities [37]. Enterprises using a diversification strategy must share production, technology, marketing, management, and other resources and play a synergistic role among different departments to enhance the total dynamic capabilities of the enterprise. Therefore, the adoption of the multidivisional structure with a related diversification strategy is appropriate. At the same time, the multidivisional structure is not applicable to an unrelated diversification strategy. If the multidivisional structure is matched with an unrelated diversification strategy, functional departments will continue to play a leading role in the business’ research and design, marketing, and other areas; this scenario does not foster flexibility and initiative in business units and can reduce the operational efficiency of unrelated diversification strategies used.

The symmetry of the effect of a diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance is shown in Table 1. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are put forward:

Table 1.

The symmetry of the effect of a diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The modeling of the use of an unrelated diversification strategy and holding company structure on financial performance is symmetric—that is, the holding company structure can more positively regulate the impact of the use of an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance than the united and multidivisional structures can.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The modeling of the use of a related diversification strategy and multidivisional structure on financial performance is symmetric—that is, the multidivisional structure can more positively regulate the impact of the use of a related diversification strategy on financial performance than the united and holding company structures can.

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample

The data used in the current study are mainly from the Wind China Financial Database. As the leading database for Chinese financial data, Wind is often cited by academic papers for its rich information, software service platforms, media, and research reports. Most listed companies are leading enterprises in various industries, which can ensure the sample’s typicality and representativeness. The present study uses Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share-listed companies.

The samples were selected according to the following steps, to ensure the validity of the research data. The first step was to eliminate all special treatment company samples, to prevent the influence of abnormal data on the analysis results. Secondly, financial and real estate companies were not considered in the data collection, because their business and organization are relatively single. Thirdly, organizational structure is not a financial index and cannot be obtained directly in batches from various databases; information about the organizational structures of the listed companies could only be gathered manually from their official websites and annual reports. However, certain enterprises do not publish details of their organizational structure in their official websites and annual reports, resulting in the data being inaccessible; thus, the samples of such companies were removed to complete the research. After the above steps, a total of 3065 samples from 613 companies, from 2012 to 2016, were collected as a research sample.

The initial data were used for a descriptive analysis. Correlation and regression analyses were carried out with the data after centralized processing. To unify the dimension, the data of all the variables were processed centrally—that is, we subtracted the mean of all the variables from the value of all the variables, to gain a new value for all the variables. Data analysis was completed by using SPSS 26.0 and EVIEWS 10.0.

4.2. Variables

4.2.1. Explained Variable

Financial performance was set as the explained variable. Financial performance can include return on asset (ROA) [38], return on equity (ROE) [39], and Tobin’s Q [28]. Among numerous financial indicators, the ROA indicator is comprehensive and can reflect the capital structure, operating results, and operational efficiency of enterprises. The ROA indicator also has a strong versatility and is not limited by the industry. Based on the study of Bettis (1981) [38], this study uses ROA as the measure of financial performance. The ROA value was enlarged 100 times, to facilitate observation, which did not affect the data structure and the results of the analysis.

4.2.2. Explanatory Variables

Unrelated and related diversification strategies were set as the explanatory variables. According to existing research, an enterprise diversification strategy has three main direct measurement methods: product calculation based on standard industrial classification (SIC) [40], the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) [41], and the entropy index [42]. Considering the research objectives of this study and referring to research on the application of the entropy index method [7,43], the entropy index formula was used to measure the diversification strategy of enterprises based on the Chinese national economic industry classification standards (GB/T4754-2002). The diversification strategy entropy index is calculated by the following formula:

where D denotes the degree of diversification strategy, n denotes the number of industries operated, and Pi denotes the proportion of business i income in the total business income of the enterprise. When other conditions remain unchanged, the number of industries involved in the enterprise operation is high, and the entropy index is also high. When an enterprise enters only one industry, the minimum value of D is 0. When the business industry is unchanged, the higher the average sales of enterprises in all industries, the higher the entropy index. When the sales are distributed equally in all industries—that is, n = l/n—the value of D is the largest.

The entropy index can measure the degree of diversification of different categories. When a proportion of business income is divided into the four-digit SIC codes, the result of Formula (1) is the total diversification index. The industry diversification index is calculated by Formula (1) when the business department is divided into two-digit SIC codes. Product diversification can be regarded as the total diversification strategy degree, whereas industry diversification can be regarded as the unrelated diversification strategy degree. The difference between them is the related diversification strategy degree, which is as follows:

where DR is the degree of related diversification strategy, DT is the degree of total diversification strategy, and DU is the degree of unrelated diversification strategy.

4.2.3. Moderator Variables

Organizational structures are set as moderator variables. According to Williamson (1975) [8], the organizational structure of an enterprise is divided into three types, namely united, holding company, and multidivisional, which are represented by the symbols OU, OH, and OM, respectively. According to the united, holding company, and multidivisional structures shown in Figure 1, the type of organizational structure can be judged by referring to the annual report and website of the enterprises. Organizational structures are virtual variables; when an organizational structure is represented by the value 1, the others remain 0.

4.2.4. Control Variables

Based on previous research [43,44], enterprise age and the asset–liability ratio were selected as control variables.

(1) Enterprise age is represented by the symbol AGE. Enterprises with different ages are in different stages of development, and their strategic choices and organizational structure designs vary. Therefore, to study the relationships between diversification strategy, organizational structure, and financial performance, the factor of enterprise age cannot be ignored. This index is expressed by the number of years between the observation period of the sample enterprise and its establishment date.

(2) The asset–liability ratio is expressed by the symbol LEV. The capital structure of an enterprise affects its capital operation and performance. Therefore, the asset–liability ratio of an enterprise is taken as a control variable, which is expressed by the asset–liability ratio disclosed in the annual report of the sample enterprise in the observation period. The LEV value is enlarged 100 times, to facilitate observation, but this enlargement does not affect the data structure and analysis results.

In sum, Table 2 shows the variables and definitions used.

Table 2.

Definition of variables.

4.3. Regression Models

4.3.1. H1 Regression Models

According to H1, the sample data are divided into unrelated and related diversification strategies, to verify the impact of diversification strategy on financial performance. The test models are as follows:

Model 1: Impact of unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 2: Impact of related diversification strategy on financial performance.

In Models 1 and 2, i denotes individuals, t denotes periods, it denotes observations of individuals i in period t, β1 is the coefficient of explanatory variables, β2 and β3 are the coefficients of control variables, αi represents constant term, and μit represents random error.

Compared with the regression results in Models 1 and 2, if the regression coefficient of DU and DR are not significant at the same time, and the regression coefficient of DR is positive and larger than that of DU, then H1 is verified.

4.3.2. H2 and H3 Regression Models

According to H2 and H3, the united, holding company, and multidivisional structures interact separately with the unrelated and related diversification strategies, to verify the moderating effects of organizational structure on the relationships between diversification strategy and financial performance. The test models are as follows:

Model 3: Regulating the role of the united structure on the impact of an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 4: Regulating the role of the united structure on the impact of a related diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 5: Regulating the role of the holding company structure on the impact of an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 6: Regulating the role of the holding company structure on the impact of a related diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 7: Regulating the role of the multidivisional structure on the impact of an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 8: Regulating the role of the multidivisional structure on the impact of a related diversification strategy on financial performance.

From Model 3 to Model 8, i denotes individuals, t denotes periods, it denotes the observations of individuals i in period t, β1 denotes the coefficient of explanatory variables, β2 denotes the coefficient of moderator variables, β3 denotes the coefficient of moderator variables and explanatory variables’ interaction terms, β4 and β5 are the coefficients of control variables, αi represents the constant term, and μit represents random error.

According to the regression results of Model 3, Model 5, and Model 7, if the regression coefficient of OH × DU is significantly positive and larger than that of OU × DU and OM × DU, then H2 is verified. According to the regression results of Model 4, Model 6, and Model 8, if the regression coefficient of OM × DR is significantly positive and larger than that of OU × DR and OH×DR, then H3 is verified.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 3 shows the results of variable descriptive statistics. The minimum value of ROA is −20.606, whereas the maximum value is 51.657, indicating a large gap in the business performance of each enterprise. The minimum value of each diversification strategy is 0, that is, the company has not chosen a diversification strategy. However, the average value of DU is 0.681, the average value of DR is 0.314, and the average value of DU is more than the average value of DR, indicating that the degree of unrelated diversification is higher than that of related diversification. The standard deviation of each diversification strategy is small, which shows little difference in the choice of diversification strategy. The average of AGE is 12.587, indicating that the sample enterprises have been established for a long time, and most of them are relatively stable continuous operation enterprises. The minimum value of LEV is 1.027, the maximum value is 91.173, and the standard deviation is large. This shows that the asset–liability ratio gap between enterprises is large. OU, OH, and OM are dummy variables, and each organizational structure was adopted by enterprises.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

5.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 4 shows the correlation between variables. ROA is significantly correlated with DR, AGE, LEV, OH, and OM, and the correlation with DU and OH is not significant. Further regression analysis is needed to test the effects of antecedents on the outcome variables. Except for the correlation between OM and DU, and OM and AGE, no significant correlation is found between other explanatory variables, and no correlation coefficient is greater than 0.5, thus indicating the absence of multicollinearity between explanatory variables.

Table 4.

Variable correlation analysis.

5.3. Regression Results

5.3.1. H1 Test Results

Table 5 shows the regression results of the impact of diversification strategy on financial performance. According to Model 1 and Model 2, explanatory variables and control variables are added to regress explained variable to test H1. The F values are all significant at the 0.01 level, indicating that each regression model has significant statistical significance.

Table 5.

Regression results of the impact of diversification strategy on financial performance.

Model 1 uses ROA as the explained variable and DU as the explanatory variable to test the impact of using an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance. The results show that the DU coefficient is −0.685, which is significant at the 0.01 level, indicating that the unrelated diversification strategy has a significant negative impact on financial performance.

Model 2 uses ROA as the explained variable and DR as the explanatory variable, to test the impact of using a related diversification strategy on financial performance. The results show that the impact of using an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance is positive but not significant.

To sum up, using an unrelated diversification strategy has a significant negative impact on financial performance, whereas the related diversification has no significant impact on financial performance. Therefore, H1 is verified, which shows that there is asymmetry between adopting a diversification strategy and financial performance, but the financial performance of firms’ using a related diversification strategy is better than that of firms’ using an unrelated diversification strategy.

5.3.2. H2 and H3 Test Results

Table 6 shows the regression results of the moderating effects of united, holding company, and multidivisional structures on the relationships between unrelated and related diversification strategies and financial performance. According to Model 3 to Model 8, explanatory variables, moderator variables, interaction of the explanatory variables and moderator variables, and control variables are added to regress explained variable to test H2 and H3. The F values are all significant at the 0.01 level, indicating that each regression model has significant statistical significance.

Table 6.

Regression results of the moderating effect of organizational structure on diversification strategy and financial performance.

Model 3 uses ROA as the explained variable, DU as the explanatory variable, and OU as the moderator variable to test the moderating effect of the united structure on the financial performance of firms’ using an unrelated diversification strategy. The results show that the regression coefficient of OU × DU is negative.

Model 4 uses ROA as the explained variable, DR as the explanatory variable, and OU as the moderator variable, to test the moderating effect of the united structure on the financial performance of firms’ use of a related diversification strategy. The results show that the regression coefficient of OU × DR is negative.

Model 5 uses ROA as the explained variable, DU as the explanatory variable, and OH as the moderator variable, to test the moderating effect of the holding company structure on the financial performance of firms’ use of an unrelated diversification strategy. The results show that the regression coefficient of OH × DU is positive but not significant, which indicates that the moderator variable OH has a positive regulating effect but that the moderating effect is not significant.

Model 6 uses ROA as the explained variable, DR as the explanatory variable, and OH as the moderator variable to test the moderating effect of the holding company structure on the financial performance of firms’ use of a related diversification strategy. The results show that the regression coefficient of OH × DR is negative.

Model 7 uses ROA as the explained variable, DU as the explanatory variable, and OM as the moderator variable to test the moderating effects of the multidivisional structure on the financial performance of firms’ use of an unrelated diversification strategy. The results show that the regression coefficient of OM × DU is negative.

Model 8 uses ROA as the explained variable, DR as the explanatory variable, and OM as the moderator variable to test the moderating effects of the multidivisional structure on the financial performance of firms’ use of a related diversification strategy. The results show that the regression coefficient of OH × DR is 1.353, which is significant at the 0.05 level, and the adjusted R2 increases from 0.130 in Model 2 to 0.136 in Model 8, indicating that the goodness of fit of the model increases after the addition of the moderator variable OM.

In conclusion, the interaction of using an unrelated diversification strategy with the united and holding company structures has significant negative impacts on financial performance, whereas it has a positive impact on financial performance by interacting with the holding company structure, but the impact is not significant. Therefore, H2 is partly verified, indicating that, compared with the united and multidivisional structures, the modeling of using an unrelated diversification strategy and holding company structure on financial performance is symmetric, and other elements should be included to improve the symmetry. The interaction of using a related diversification strategy with the united and holding company structures has negative impacts on financial performance, whereas it has a significant and positive impact on financial performance by interacting with the multidivisional structure. Therefore, H3 is verified, indicating that, compared with the united and holding company structure, the modeling of using a related diversification strategy and multidivisional structure on financial performance is symmetric.

5.4. Robustness Test

The robustness of the models was tested by replacing the explained variables, and ROA was replaced with ROE. ROE, which is return on equity, was also often used to represent the financial performance of enterprises [39]. Table 7 shows the robustness of the test results. The F values of Model 1 to Model 8 are all significant at the 0.01 level, indicating that each model has significant statistical significance. According to the regression results of Model 1 and Model 2, the coefficient of DU is significantly negative, whereas the coefficient of DR is negative but not significant. Therefore, H1 is verified. According to the regression results in Model 3 to Model 8, the coefficients of OU × DU and OH × DU are negative, and the coefficient of OH × DU is positive; however, the moderating effect is not significant, indicating that H2 is partly verified. The coefficients of OU × DR and OH × DR are negative, and the coefficient of OM × DR is significantly positive, indicating that H3 is verified. To sum up, the regression results with ROE as the explained variable are consistent with those with ROA as the explained variable, showing that all the models are robust.

Table 7.

Results of the robustness test.

6. Conclusions

This study adopted the empirical research method; constructed symmetric modeling of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance; measured the degree of using unrelated and related diversification strategies, with the entropy index method; divided organizational structure into the categories of united, holding company, and multidivisional; represented financial performance via ROA; took enterprise age and the asset–liability ratio as the control variables, and selected the sample data from Chinese listed enterprises, from 2012 to 2016, to test the impacts of using unrelated and related diversification strategies on financial performance and the moderating effects of organizational structures on such relationships. The following conclusions were drawn from empirical analysis.

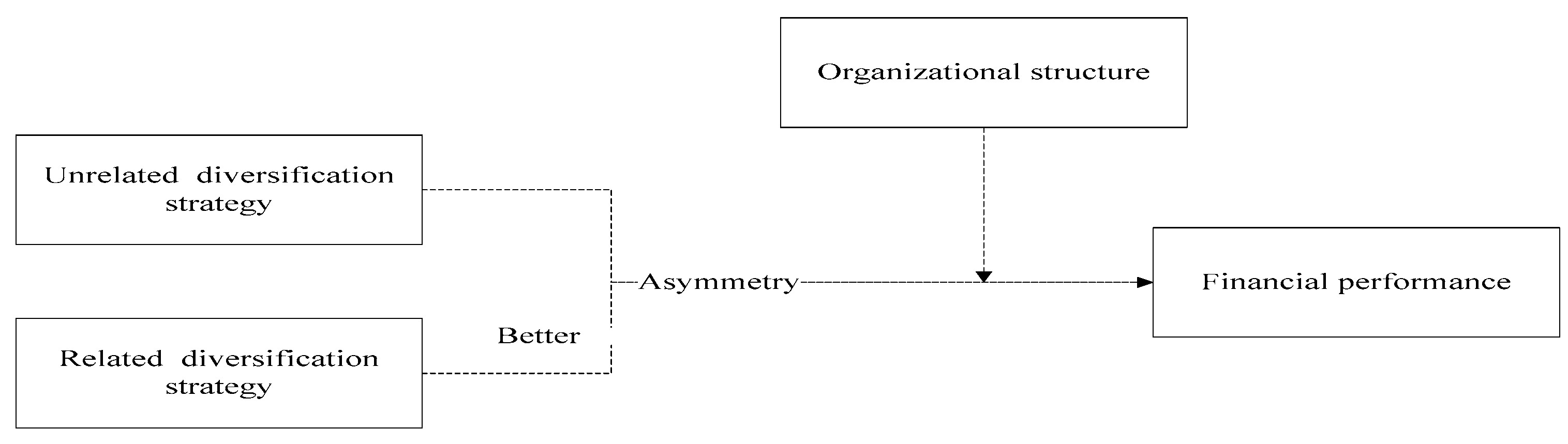

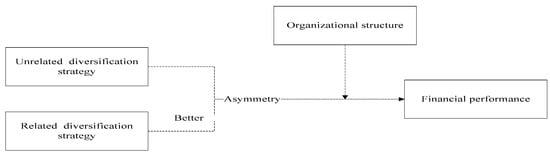

Firstly, the impacts of firms’ use of unrelated and related diversification strategies on their financial performance were explored. The asymmetry of the degree of using a diversification strategy on financial performance is shown in Figure 2. Neither unrelated diversification strategy nor related diversification strategy has a significant positive impact on financial performance, but the impact of the use of a related diversification strategy on financial performance is more positive than that of the use of an unrelated diversification strategy. However, this is not to say that enterprises cannot choose to use an unrelated diversification strategy. When an enterprise proposes the use of an organizational structure that is symmetric with an unrelated diversification strategy, it is still possible to achieve an excellent financial performance. The above conclusion based on our sample of Chinese enterprises is consistent with the conclusions of researchers studying firms in other countries [7,13], proving that the economics-of-scope theory is also valid for diversified business operations in China [12].

Figure 2.

The asymmetry of the degree of diversification strategy on financial performance.

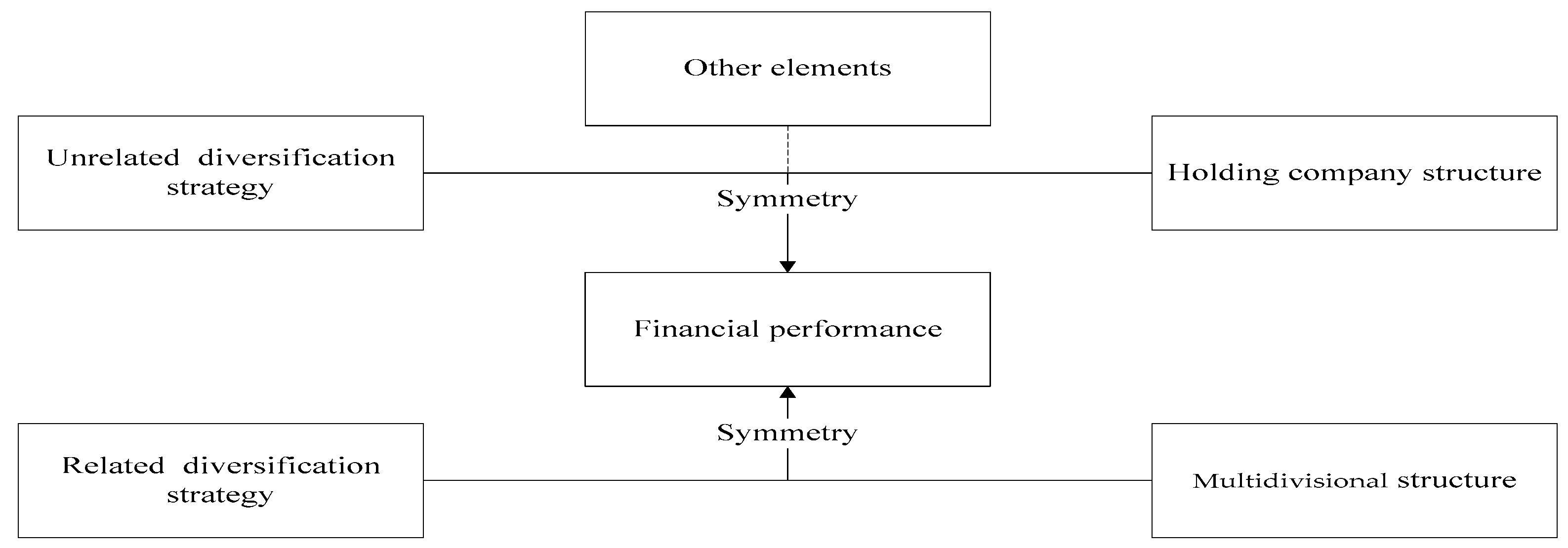

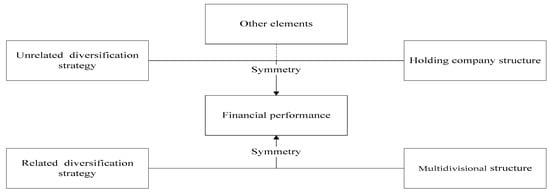

Secondly, this study examined the moderating effects of the united, holding company, and multidivisional structures on the impacts of the use of unrelated and related diversification strategies on financial performance. The symmetry of the effect of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance is shown in Figure 3. Organizational structure is an important element of the internal management system of diversified enterprises. Adopting an organizational structure that is symmetric with the diversification strategy is conducive to the improvement of financial performance. The holding company structure has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between an unrelated diversification strategy and financial performance; however, the moderating effect is not significant, indicating that the effect of the use of the holding company structure and an unrelated diversification strategy on financial performance is partly symmetric, and other elements should be included to improve the symmetry. The multidivisional structure positively moderates the relationship between a related diversification strategy and financial performance, indicating that the effect of the use of the multidivisional structure and a related diversification strategy on financial performance is symmetric. These conclusions verify the notion that the configural organization theory can provide a theoretical basis for the design of the organizational structure of diversified enterprises [30], and a more specific organizational structure design suitable for different types of diversification strategy is put forward, which further develops the view of the structure-follows-strategy theory that the multidivisional structure is applicable to the total diversification strategy [14].

Figure 3.

The symmetry of the effect of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance.

7. Discussion

The findings have certain economic and commercial significance. Specifically, they can provide a theoretical basis for enterprises to preferentially choose which type of diversification strategy and design organizational structure to match unrelated and related diversification strategies, to improve their financial performance. As for the choice of diversification strategy type, it is suggested that enterprises should preferentially use a related diversification strategy and be cautious in choosing an unrelated diversification strategy that may hinder the financial performances of the enterprise. As for the design of the organizational structure, adopting an unrelated diversification strategy with a holding company structure may be considered. Enterprises enter industries with low or no correlation that, at the same time, have a certain complexity in operation. The organizational structure needs a certain degree of decentralization, and the holding company structure can meet the needs of multi-business autonomy and flexible operation to the greatest extent. However, a symmetric organizational structure is not enough; this approach needs to use management control, human resource management, corporate culture, and other elements together. It is suggested that enterprises adopt a related diversified strategy, and a multidivisional structure should be established as far as possible. When adopting a related diversification strategy, the two functions of strategic decision-making and operational decision-making in the profit center should be effectively separated, and the centralized control of a company and the decentralized operation of a business unit should be considered. By using a multidivisional structure, the synergy of new and old businesses will be maximized.

This study has a generalized value for Chinese enterprises and the countries that carry out investment cooperation with Chinese enterprises. The sample enterprises are representative listed Chinese enterprises and span a wide range of industries, regions, and ownership structures, indicating that the findings can provide a reference point for most enterprises in China. At the same time, China is the second largest economy and the largest emerging economy in the world. As of 2020, 133 Fortune 500 companies are operating in China. In recent years, with the saturation of the country’s local market and the gradual rise in the price of labor, Chinese enterprises have increasingly invested in other countries, and the internationalization of Chinese enterprises has been greatly accelerated. Diversification strategies are an important strategic mode of international investment for multinational enterprises. Numerous studies have found that the home environment is an important factor influencing the effect of implementing a diversification strategy in multinational enterprises [6,45]. Therefore, understanding the diversified business environment of Chinese enterprises is conducive to win–win cooperation between an investee country and Chinese enterprises.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Whether the research results can be extended to other countries is unclear, and the differences between various industries and fields of activity in the analyzed enterprises are also unclear. The results reveal that the financial performance of diversified enterprises is closely related to the institutional environment [46,47]. This study used data only from A-share-listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen, from 2012 to 2016, as its research object. In the future, we expect that scholars will expand this research to other countries and industries, and further try to use meta-research methods to cluster the institutional environments of different countries and industries, based on a sufficient number of research samples. Through such an approach, future researchers can explore the symmetry of the effect of diversification strategy and organizational structure on financial performance under different institutional environments and provide more specific suggestions on diversification strategy choice and organizational structure design for enterprises in different countries and industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W.; supervision, C.W.; writing—original draft, J.C., H.G. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Project of North Minzu University, grant number 2020XYSGY01, and the National Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 2013GZSG0333.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the input from the editors and anonymous reviewers who contributed to improving the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, D.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Wu, Y. Stakeholder Symbiosis in the Context of Corporate Social Responsibility. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.-S.; Chuang, K.-C.; Li, H.-X.; Tu, J.-F.; Huang, H.-S. Symmetric Modeling of Communication Effectiveness and Satisfaction for Communication Software on Job Performance. Symmetry 2020, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, J.; Guo, H.; Wu, X. Research on Collaborative Planning and Symmetric Scheduling for Parallel Shipbuilding Projects in the Open Distributed Manufacturing Environment. Symmetry 2020, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. Strategies for diversification. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1957, 35, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Purkayastha, S.; Manolova, T.S.; Edelman, L.F. Diversification and Performance in Developed and Emerging Market Contexts: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirca, A.H.; Roth, K.; Hult, G.T.M.; Cavusgil, S.T. The role of context in the multinationality-performance relationship: A meta-analytic review. Glob. Strategy J. 2012, 2, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palepu, K. Diversification strategy, profit performance and the entropy measure. Strateg. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Ó. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications: A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization. 1975. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1496220 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Tsai, H.T.; Ren, S.C.; Eisingerich, A.B. The effect of inter- and intra-regional geographic diversification strategies on firm performance in China. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Au, K.; Yi, L. Diversification Strategy, Ownership Structure, and Financial Crisis: Performance of Chinese Private Firms. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2018, 47, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.H.; Tang, Y.J.; Su, S.W. R&D internationalization, product diversification and international performance for emerging market enterprises: An empirical study on Chinese enterprises. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Economies of scope and the scope of the enterprise. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1980, 1, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palich, L.E.; Miller, L.B.C.C. Curvilinearity in the diversification–performance linkage: An examination of over three decades of research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 21, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.H. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise. By Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. (Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press, 1962. xvi + 463 pp. Charts, references, notes, and index. $10.00.). J. Am. History 1962, 49, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M. Green investment strategies and bank-firm relationship: A firm-level analysis. Econ. Bull. 2018, 38, 2225–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Falcone, P.M. Environmental regulation and green investments: The role of green finance. Int. J. Green Econ. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, M.; Richter, A.; Karna, A. Does the Diversification-Firm Performance Relationship Change Over Time? A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 270–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H. Literature Review on Diversification Strategy, Enterprise Core Competence and Enterprise Performance. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2019, 9, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Lou, Y.; Cheng, K.; Yang, X. Diversification and corporate performance: Evidence from china’s listed energy companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.M.; Cui, T.; Nie, R.; Lin, H.; Shan, Y.L. Does diversification help improve the performance of coal companies? Evidence from China’s listed coal companies. Resour. Policy 2019, 61, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, J. Effectiveness of diversification strategies for ensuring financial sustainability of construction companies in the Republic of Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Chen, C.J.; Guo, A.R.S.; Lin, Y.H. Strategy, capabilities, and business group performance: The endogenous role of industry diversification. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amburgey, T.L.; Dacin, T. As the left foot follows the right? The dynamics of strategic and structural change. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1427–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan, J.I.; Sanchez-Bueno, M.J. The continuing validity of the strategy-structure nexus: New findings, 1993–2003. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, J.M.; Kedia, S. Explaining the diversification discount. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 1731–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Servaes, H.; Zingales, L. The cost of diversity: The diversification discount and inefficient investment. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 35–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.N.; Chu, W.Y. Diversification, resource concentration, and business group performance: Evidence from Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, L.H.P.; Stulz, R.M. Tobin’s Q, Corporate Diversification and Firm Performance. J. Polit. Econ. 1993, 102, 1248–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavas, J.P.; Kim, K. Economies of diversification: A generalization and decomposition of economies of scope. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 126, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Configurations Revisited. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, A.H.; Ganco, M.; Hinings, C.R. Returning to the Frontier of Contingency Theory of Organizational and Institutional Designs. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 393–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayne Gary, M. Implementation strategy and performance outcomes in related diversification. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawley, E. Diversification, coordination costs, and organizational rigidity: Evidence from microdata. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Tirole, J. Formal and real authority in organizations. J. Polit. Econ. 1997, 105, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.W.; Hitt, M.A.; Hoskisson, R.E. Cooperative versus competitive structures in related and unrelated diversified firms. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. The Impact of the Multi-divisional Structure on Organizational Slack: The Contingency of Diversification Strategy. Br. J. Manag. 1998, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Døving, E.; Gooderham, P.N. Dynamic capabilities as antecedents of the scope of related diversification: The case of small firm accountancy practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettis, R.A. Performance differences in related and unrelated diversified firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 1981, 2, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, P.D. PE Ratios, PEG Ratios, and Estimating the Implied Expected Rate of Return on Equity Capital. Account. Rev. 2004, 79, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, V.; Varadarajan, P. Research on corporate diversification: A synthesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 523–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.H. Corporate growth and diversification. J. Law Econ. 1971, 14, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, A.P.; Berry, C.H. Entropy measure of diversification and corporate growth. J. Ind. Econ. 1979, 27, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Hitt, M.A.; Johnson, R.A.; Moesel, D.D. Construct validity of an objective (entropy) categorical measure of diversification strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.P.; David, P.; Yoshikawa, T.; Delios, A. How capital structure influences diversification performance: A transaction cost perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1013–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleilate, J.M.G.; Magnusson, P.; Parente, R.C.; Alvarado-Vargas, M.J. Home Country Institutional Effects on the Multinationality-Performance Relationship: A Comparison between Emerging and Developed Market Multinationals. J. Int. Manag. 2016, 22, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.; Capone, G. Institutions and diversification: Related versus unrelated diversification in a varieties of capitalism framework. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1902–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, K.; Purkayastha, S.; Petitt, B.S. How do institutional transitions impact the efficacy of related and unrelated diversification strategies used by business groups? J. Bus. Res. 2017, 72, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).