1. Introduction

Structured databases, as opposed to unstructured ones, are characterized by the existence of a format or some form of organization, which make them searchable in a relational fashion. In turn, structured data are amenable to spatial search algorithms, i.e., algorithms taking into account the spatial organization of the dataset. Usually this is done using tools from graph theory, and exploiting the structure of links within the database. In this framework, quantum spatial search [

1] is the problem of finding a marked element in a structured database using the quantum dynamics of a walker over a graph, as opposed to a classical one [

2]. Quantum spatial search may be thus considered a generalization of the Grover search algorithm [

3] to problems where some form of data structure is available.

Among the possible implementations, it has been shown [

4] that continuous-time quantum walks (CTQWs) over graphs may provide exact solutions to the search problem for certain graph topologies, i.e., exact localization (with unit probability) of the walker on some given target state. Additionally, the time needed to have the walker localized may be of the order

[

5], where

N is the size of the graph. This is largely outperforming any classical algorithm, where the searching time is at least of the order

. Among the different graphs, the class of those achieving exact localization in a searching time

includes the complete and the hypercube graphs of any size, and the

d-dimensional lattice of any size for

. Recently, the star graph has been added to this short list [

6,

7]. Quantum search based on CTQWs have received large attention in the recent years [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, although the high connectivity and global symmetry of the graph have been proven not to be necessary for fast quantum search [

15,

16], CTQWs are known to perform poorly on realistic graphs with low connectivity, e.g., the ring graph [

17].

Since the ring graph, and other similar graphs with low connectivity, may be of interest in view of possible implementations, a question arises on whether there exist alternative algorithms that make it possible to improve quantum search on simple graphs. In this paper, we address this problem and put forward an alternative search algorithm, based on structuring the oracle operator, which allows one to improve the localization properties of the walker by tuning only the on-site energies of the graph, i.e., without altering the topology of the graph itself. The proposed algorithm is thus suitable for implementation in systems with low connectivity, e.g., ring of quantum dots or superconducting circuits, and may be of interest for implementation of quantum search in condensed matter systems. As we will see in the following, the novel algorithm provides an overall faster strategy for quantum search, i.e., it increases the walker’s probability to reach a specific site, while decreasing the overall time needed to ensure the localization in that target. Besides quantum search, we foresee applications in the field of quantum probing [

18].

The paper is structured as follows. In the next Section, we briefly review quantum spatial search on graphs and introduce notation. In

Section 3 we discuss the use of a structured oracle to improve the searching performance of CTQW on ring graphs.

Section 4 closes the paper with some concluding remarks.

2. Quantum Spatial Search on Graphs

In several systems of interest for condensed matter, the dynamics of particles or quasi-particle (excitations) may be effectively described using the concept of continuous-time quantum walks. In CTQW one assumes that the particle may reside only on a discrete set of sites, which replaces the continuum spatial domain. A graph structure thus naturally emerges, with the set of possible position states mapped to the vertex set V of some graph G. The presence of an edge connecting two sites of the graph means that the particle may tunnel between those two sites.

Quantum spatial search on graphs is usually implemented using quantum walkers with (dimensionless) Hamiltonians of the form

where

L is the Laplacian matrix of the graph,

is the so-called oracle operator, and

is a tunable coupling, whose meaning and use will be discussed later. The Hilbert space of the walker is

where

N is the size of the graph, i.e., the number of vertices. The standard basis

,

is made of localized states, i.e., describing the walker sitting on a given site of the graph. The Laplacian is defined as

where

A is the

adjacency matrix of the graph, i.e., a square matrix with elements

, with

iff the sites

j and

k are connected, i.e., the walkers may tunnel between the two sites, and zero otherwise. The matrix

D is instead a diagonal matrix, known as the

degree matrix of the graph, with elements

, being

the number of links originating from site

j, i.e., the number of decay channels for a walker localized in

j.

A quantum spatial search on graphs consists of preparing the walker in an initially delocalized state

which can be allowed to evolve according to the Hamiltonian in Equation (

1). The goal is that of

localizing, in the shortest time, the walker on a specific site

, i.e., the

target state encoding the solution

of the search (here, for the sake of simplicity, we focus on the simple case of a unique solution, but our analysis can be straightforwardly extended to a general number

M of solutions). The task of optimally design quantum spatial search on graph thus consists of looking for an oracle

and a coupling

quickly maximizing the localization probability

The figures of merit to assess whether quantum spatial search may be implemented on a given graph structure are therefore: (1) the maximum achievable value of the localization probability in Equation (

3), and (2) the

search time , i.e., the time needed to achieve the maximum of the localization probability

. For the localization probability, the benchmark value is of course

, whereas for the search time, the benchmark is given by the

Grover (dimensionless) time

, i.e.,

, taking into account the optimal value of

.

For a complete graph of any size, quantum spatial search may be exactly implemented, i.e., we may achieve

, with

. This is obtained by choosing the oracle as the projector over the target

. In turn, the Laplacian of the complete graph is given by

, and the Hamiltonian in Equation (

1) may be exactly diagonalized. The localization probability in Equation (

3) may be thus written as

which is maximized,

, for

and

. Results are of course independent on the specific choice of the target

w, owing to the full symmetry of the complete graph.

Realistic physical structures, however, are not usually fully connected, and a question thus arises on whether it is possible to effectively implement quantum spatial search on graphs with lower connectivity, e.g., the paradigmatic example of the ring (cycle) graph. Using the same oracle

, together with the Laplacian of the ring graph

(boundary conditions:

and

) the resulting search performance is rather poor, and degrades with

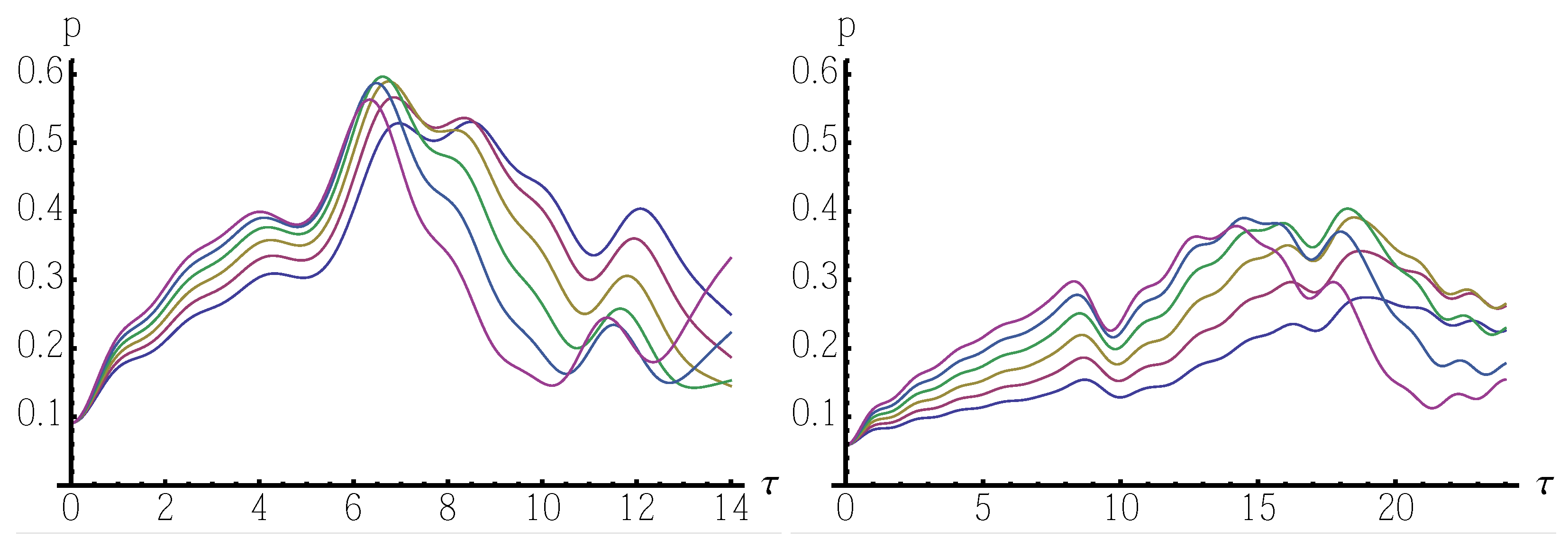

N. For the sake of illustration, in

Figure 1 we show the localization probability

as a function of

t for two ring graphs with

and

, and for different values of

(chosen among those maximizing the localization probability for short time). Also for the ring graph we have full symmetry, and thus results do not depend on the choice of the target.

3. Quantum Search by Structured Oracles

In this Section we explore the possibility of using a structured oracle in order to improve the searching performance of CTQW on ring graphs. The idea is that of going beyond the simple projector structure, however without altering the topology of the graph. In other words, we allow ourselves to tune only the on-site energies of the graph by choosing an oracle operator

(no longer a projector) that, in general, can be written in the form

where

still refers to the unique solution of the search problem. In principle, the ability of a walker with Hamiltonian

to localize at the target state

may be assessed by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian

, and then maximizing the probability

by brute force. However, this task becomes quickly unfeasible as far as

N increases, and an educated guess would be very much welcome.

In order to gain some insight into the problem, we start by considering the following three-site symmetric oracle operator

which is made of the usual oracle plus the projectors over the neighbouring sites. In particular, we analyze the effect of the sign and amplitude of the on-site energy

on the localization probability

of the ring graphs. Numerical evidence suggests that larger localization probabilities are obtained when

is smaller than

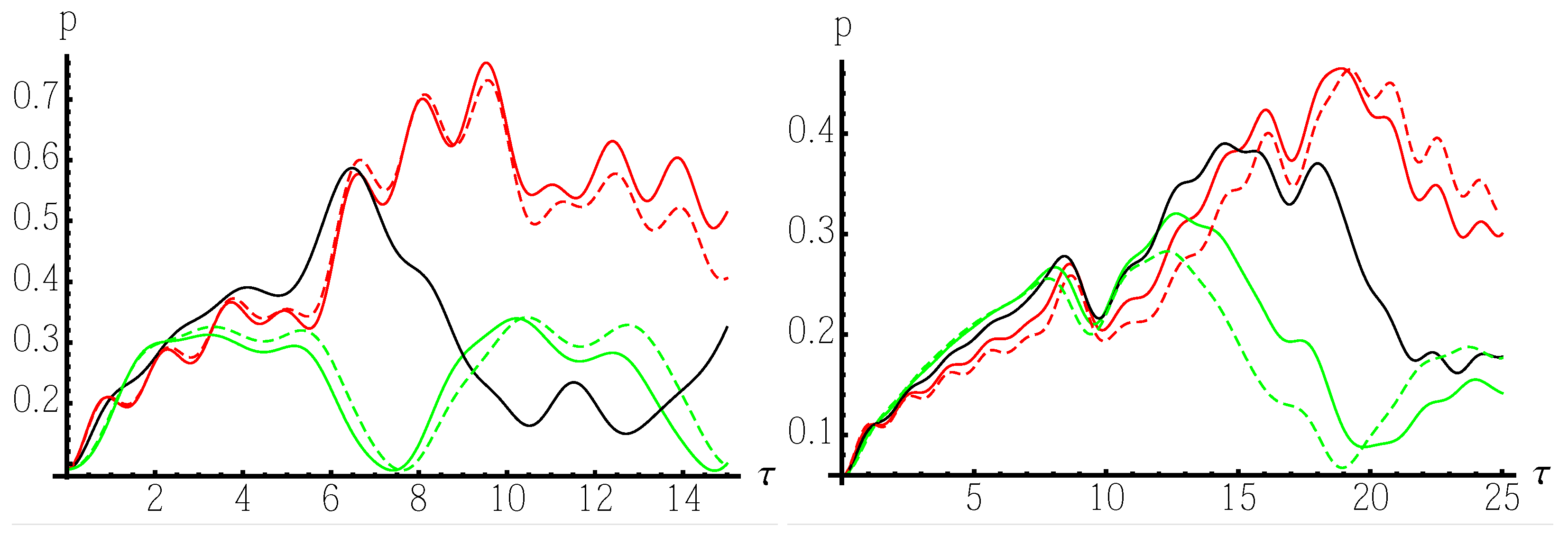

and with opposite sign. An illustrative example is reported in

Figure 2, where we show the localization probability

as a function of

for the same graphs of

Figure 1, i.e., two ring graphs with

and

. The black line in both panels denotes the localization probability

, i.e., the result obtained without the additional terms in the oracle, and corresponding to the value of

achieving maximum localization probability (i.e.,

for

and

for

).

The red curves in both panels of

Figure 2 denote the results obtained for negative values of

, whereas the green ones are for positive values of

. Solid lines in the left panel correspond to

and dashed lines to

. In the right panel we have

(solid lines) and

(dashed lines). As it is apparent from the plots, the inclusion of additional terms in the oracle is an effective strategy to achieve larger localization probability, although at later times. A systematic analysis for graphs of dimensions

confirms that larger localization probabilities are obtained when

is smaller than

and with opposite sign. Another general feature that may be observed is that with

the maximum value of the localization probability is achieved at later times.

A intuitive explanation of the behaviour of the walker goes as follows. The difference between the on-site energy of target and those of its neighbouring sites creates a barrier which slows down the walker. However, the same fact also leads to a trapping effect which allows the walker to localize more efficiently to the target.

Motivated by the above results and considerations, let us now consider a two-parameter structured oracle of the form

and try to optimize the performance by choosing suitable values of

and

c. Instead of using brute force numerical optimization, we set the values of the two parameters using the following argument. Since the evolution is unitary, the Hamiltonian is a constant of motion and we have

for any integer

k and any pair of initial

and evolved

states. In our case, the initial state is the fully delocalized state

, and the desidred final state is the target

. Since the localization is not exact, i.e.,

is not the exact final state of the evolution, we cannot hope that the all the equalities

are satisfied. However, we may use these constraints to obtain suitable values of the oracle parameters. In particular, let us consider the value

. Since

for any Laplacian, and that

from Equation (

7), the equalities

, and

may be written as

Numerical counterexamples show that for a given

n, the solutions of Equations (

8) and (9)

do not, in general, coincide the exact values found by numerical maximization of

. However, they represent a suitable approximation and, as we will see in the following, they improve the localization probability, and the search time, in comparison to the case of a simple unstructured oracle. For these reasons, we refer to

in Equation (

7) with the parameters found by the Hamiltonian constraints Equations (

8) and (9) as a

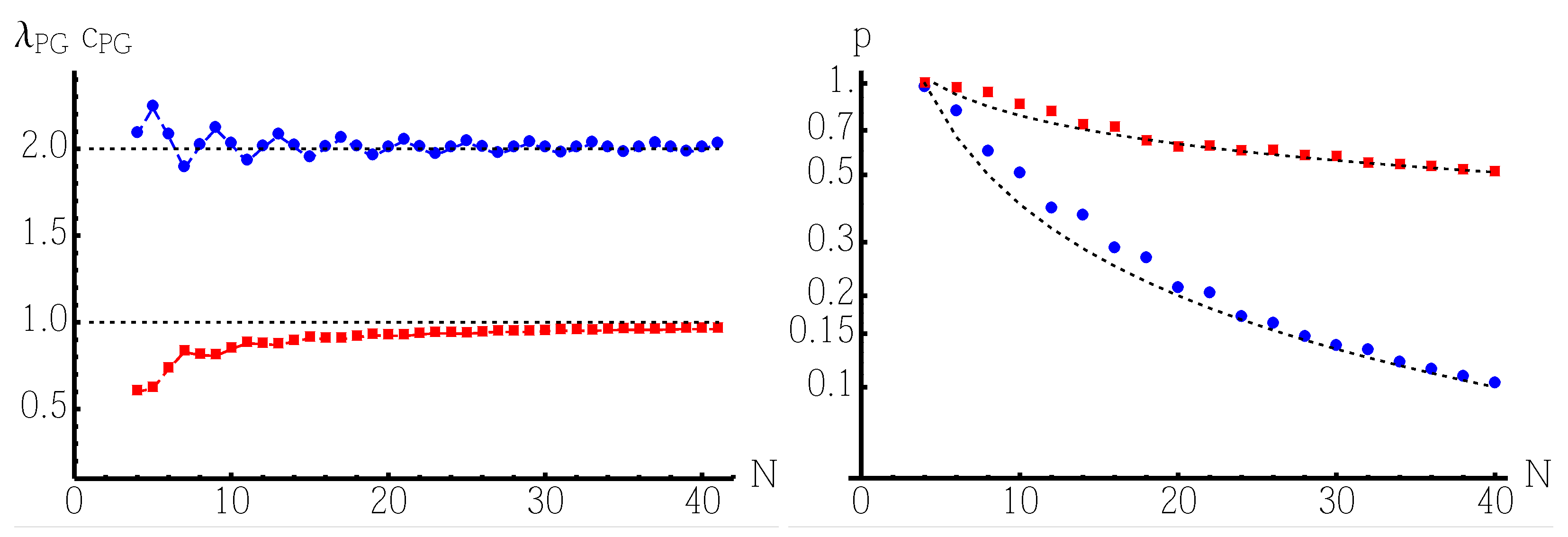

pretty good oracle (PGO). The solutions of Equations (

8) and (9), denoted by

and

, are reported in the left panel of

Figure 3 as a function of N. The value of

oscillates around the value

(the oscillation amplitude decreases with

N), whereas

increases with

N, approaching the limiting value

from below. The corresponding localization probability, i.e.,

is reported, as a function of the graph size

N, in the right panel of

Figure 3, together with the localization probability obtained with an unstructured oracle. The improvement is apparent. In the range of

N considered, the localization probability decreases as

with an unstructured oracle and only as

for a structured PGO.

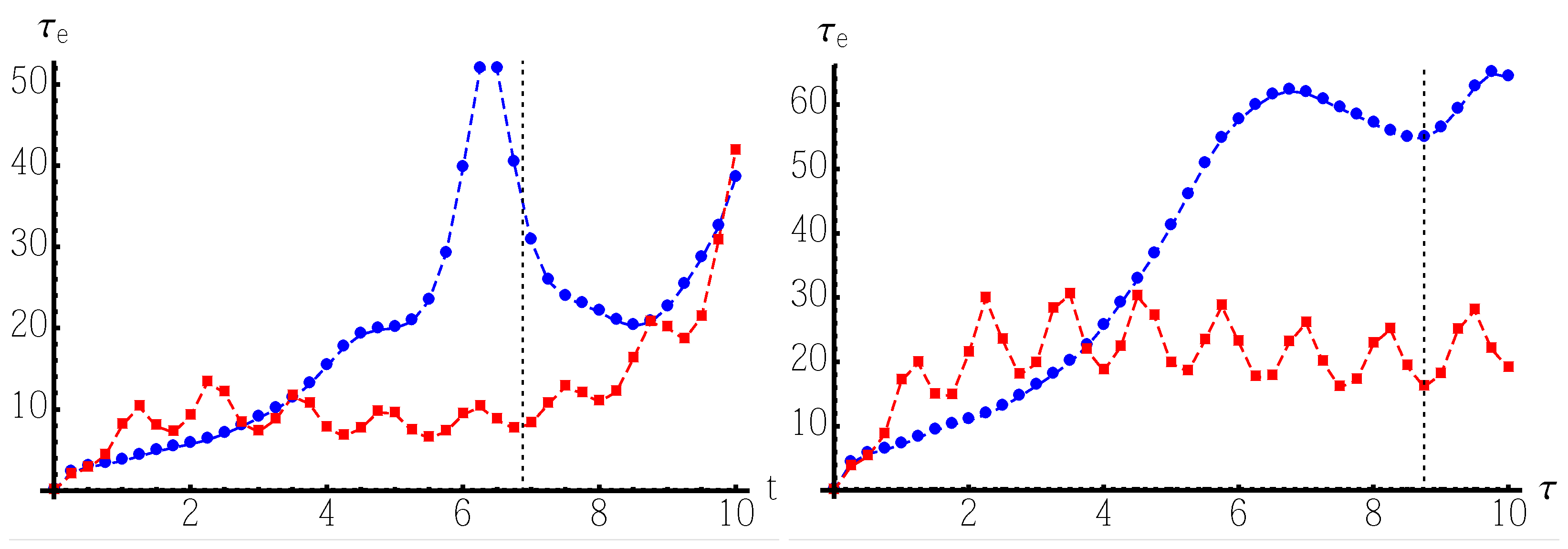

Let us now address the performance of our structured PGO in terms of the search time. If one consider search algorithm where localization is not exact, i.e., the localization probability is not one, localization should be intended in statistical sense, i.e., obtained in average by repeating experiments. In this framework, a suitable figure of merit to compare different algorithms and regimes is given by the equivalent time

obtained by renormalizing time by the corresponding localization probability. In the two panels of

Figure 4, we show the equivalent time

of PGO compared to the corresponding equivalent time

of an unstructured oracle for two ring graphs with sizes

and

.

In both panels, the red squares denotes

for our PGO, and the blue circles

for an unstructured oracle. The vertical dashed line indicates the time at which the maximum PGO localization probability is obtained. The interpretation of the results reported in

Figure 4 is the following: the equivalent time of PGO is not always lower than that of an unstructured oracle, but it becomes much smaller for times corresponding to the maximum localization probability. Overall, this means that despite the dynamics of the walker is slower with a PGO (see above), the gain in the localization probability make it convenient also in terms of the equivalent search time, which is closer to the Grover time compared to the corresponding quantity evaluated for an unstructured oracle.

Physical implementations of quantum search on graphs may require going beyond the projector structure, since acting on single sites may be difficult to implement. Our analysis shows that taking into account some modification of the on-site energies of the sites neighbouring the target one, it is still possible to obtain some effective improvement up to suitably control the phase and coupling of the different involved sites, as we highlighted in Equation (

7).

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have addressed spatial quantum search with quantum walks on graphs, and put forward an alternative search algorithm based on structuring the oracle operator. Our protocol allows one to improve the localization properties of the walker by tuning only the on-site energies of the graph, i.e., without altering its topology. In particular, we have analyzed the use of a structured oracle in order to improve the searching performance of CTQW on ring graphs, as a paradigmatic example of structure with low connectivity.

We have employed a two-parameter oracle operator and instead of using brute force numerical optimization, we have set the values of the two parameters using Hamiltonian constraints. The resulting oracle is not necessarily the optimal one, but it nevertheless provides improved performance compared to that of an unstructured oracle. We thus refer to our design as a pretty good oracle (PGO). We have considered ring graphs with size and, in the range of N considered, have found that the localization probability decreases as with an unstructured oracle and only as for a structured PGO.

The proposed algorithm is suitable for implementation in systems with low connectivity, e.g., ring of quantum dots or superconducting circuits, whereas characterization of oracle parameters may be achieved by quantum probing [

19,

20,

21].