Inflation in Supergravity from Field Redefinitions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transformation of the Kähler Potential

3. Prototypes of Models

3.1. Monomial Models

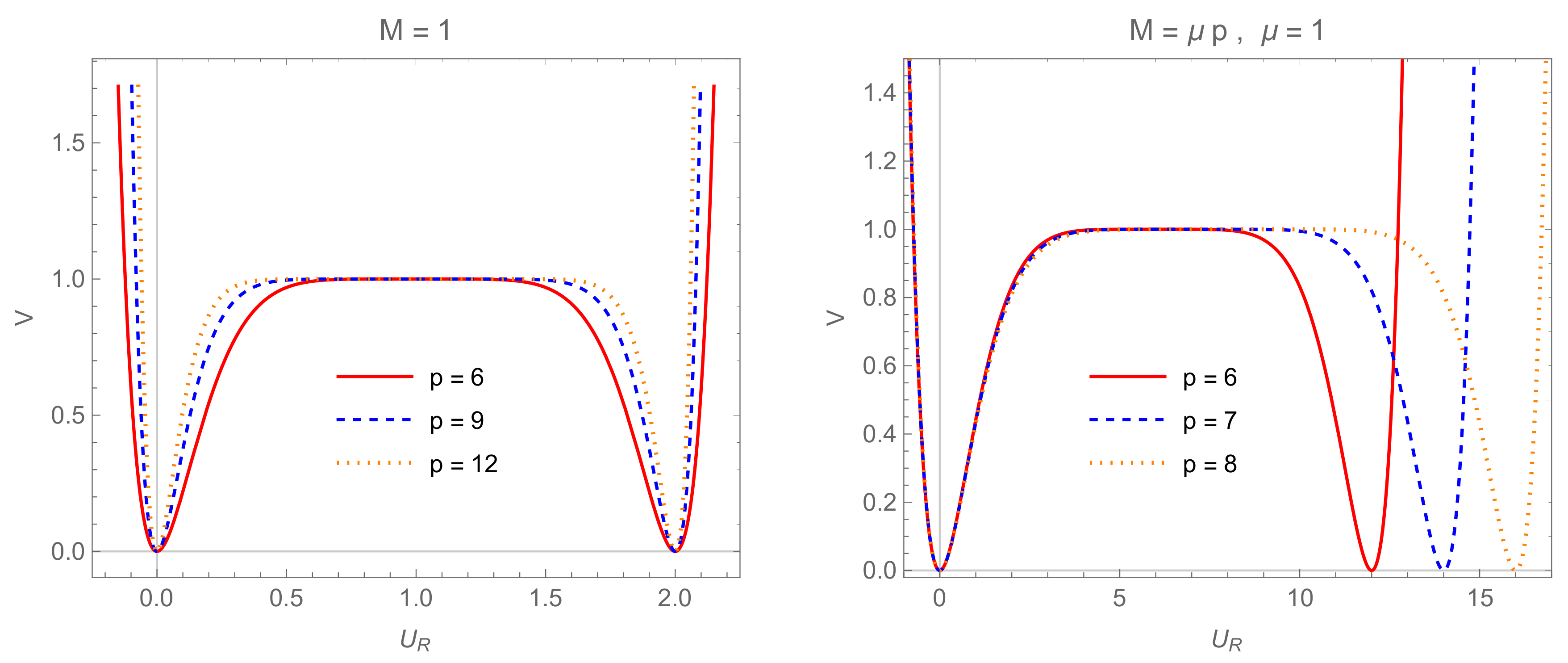

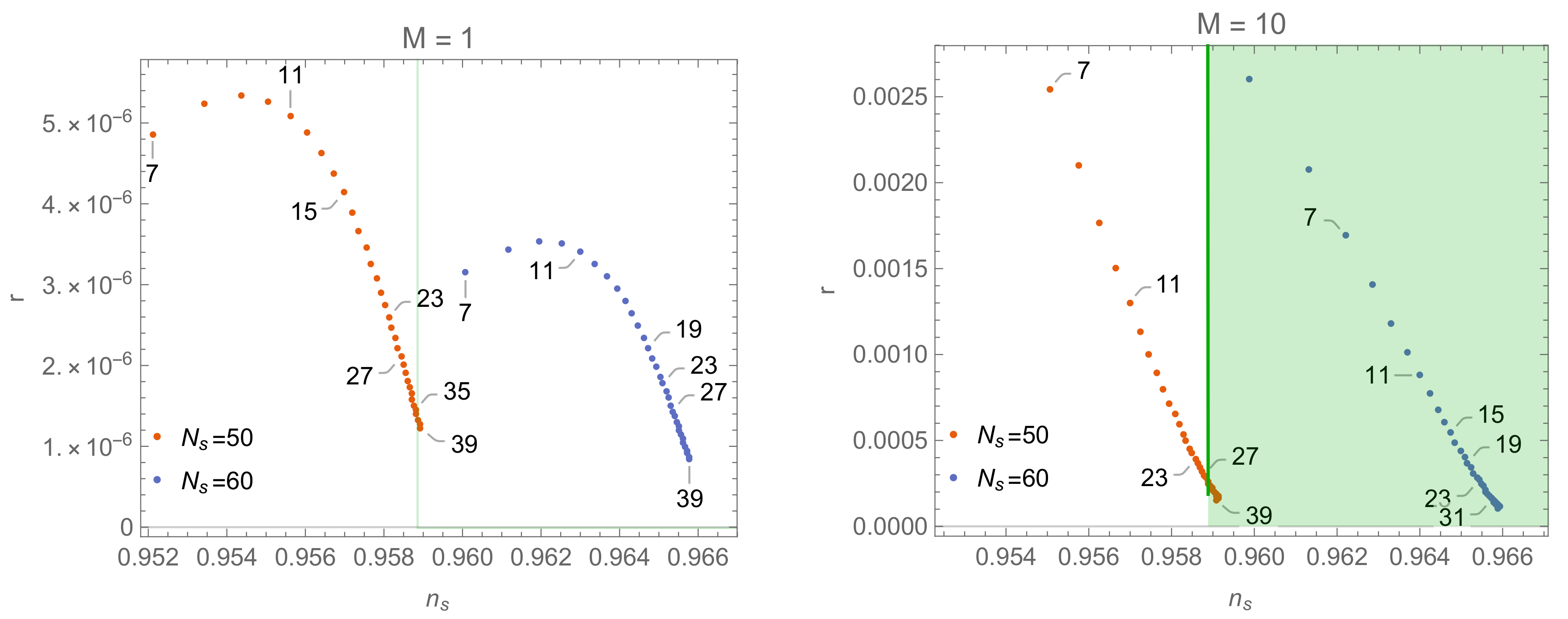

3.2. Locally Flat Potentials

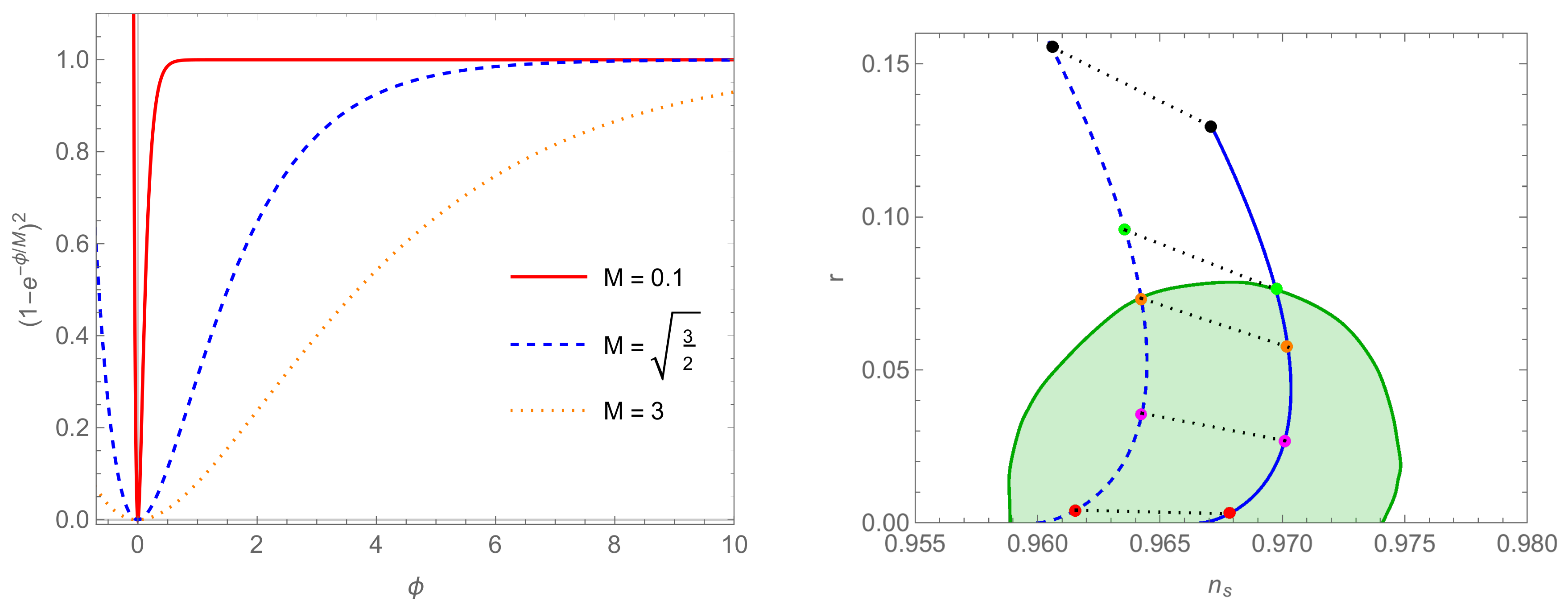

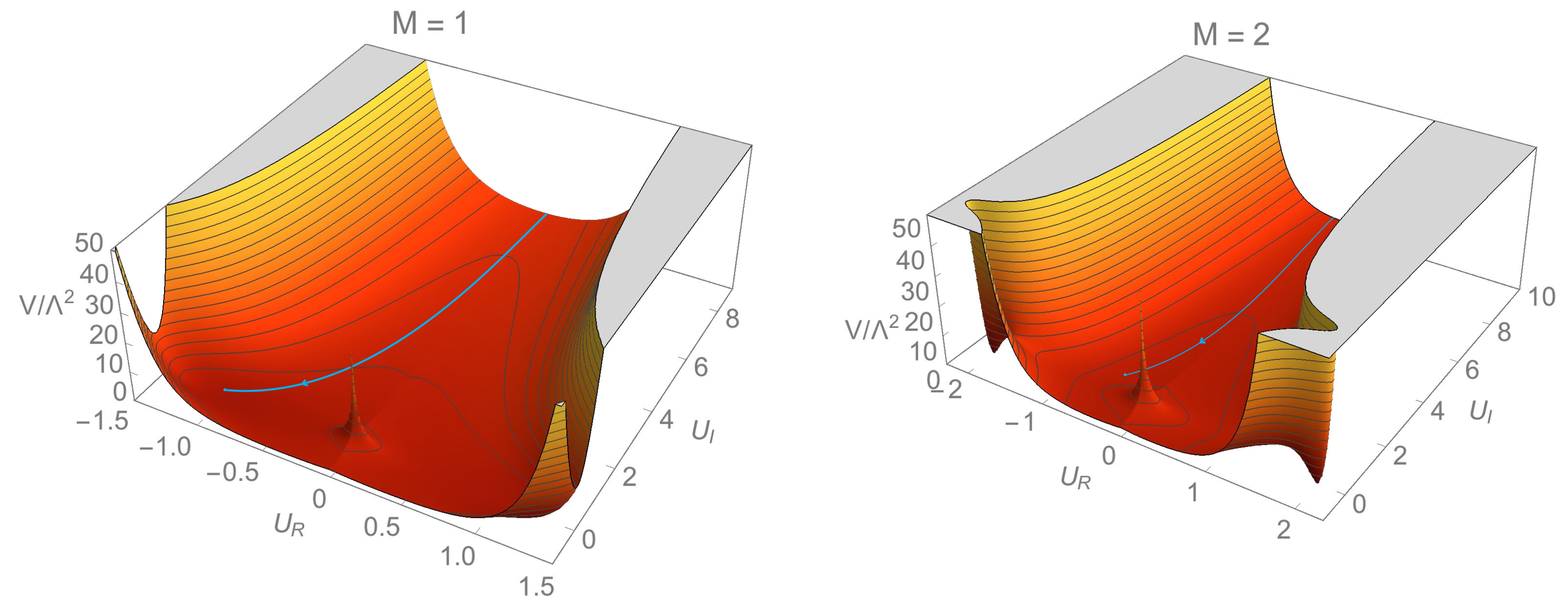

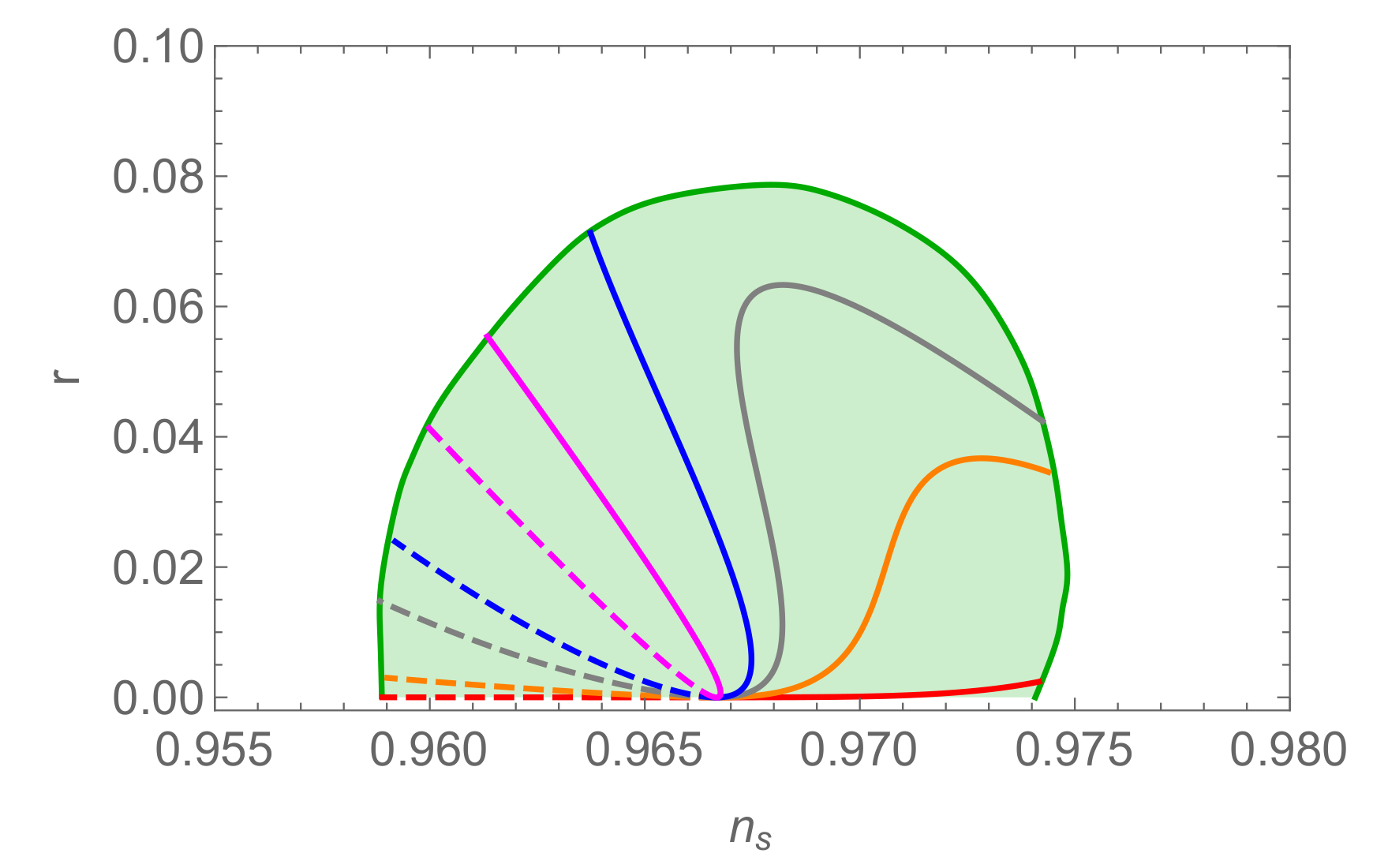

3.3. Generalization of the Starobinsky Inflation

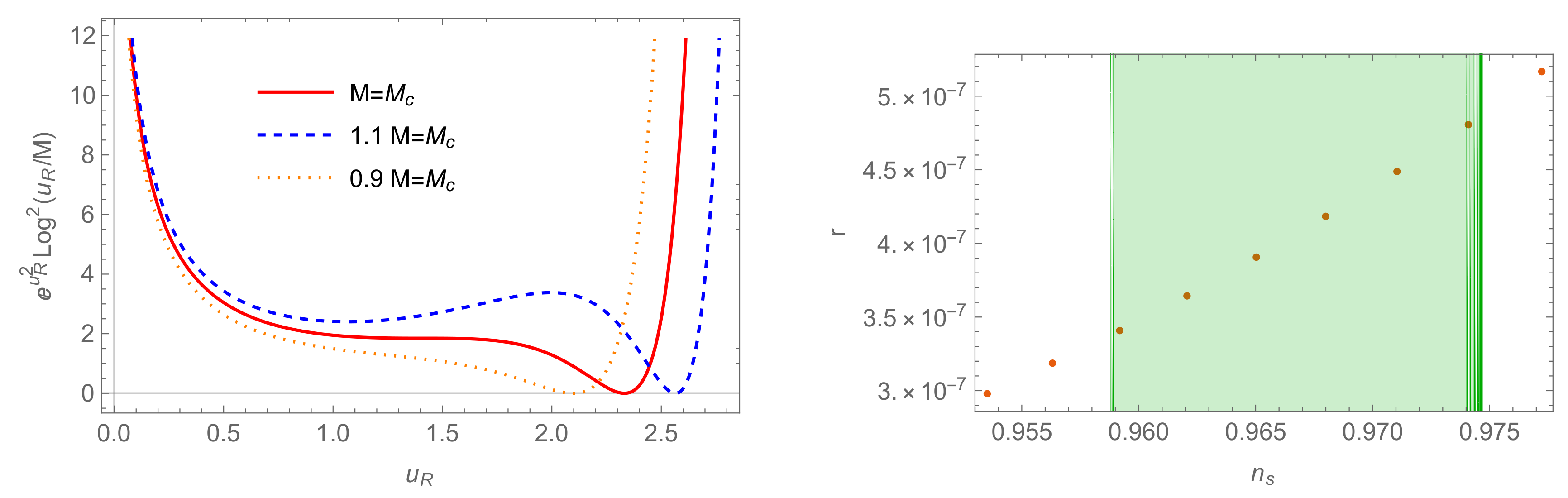

3.4. The Log Model for

The Scenario

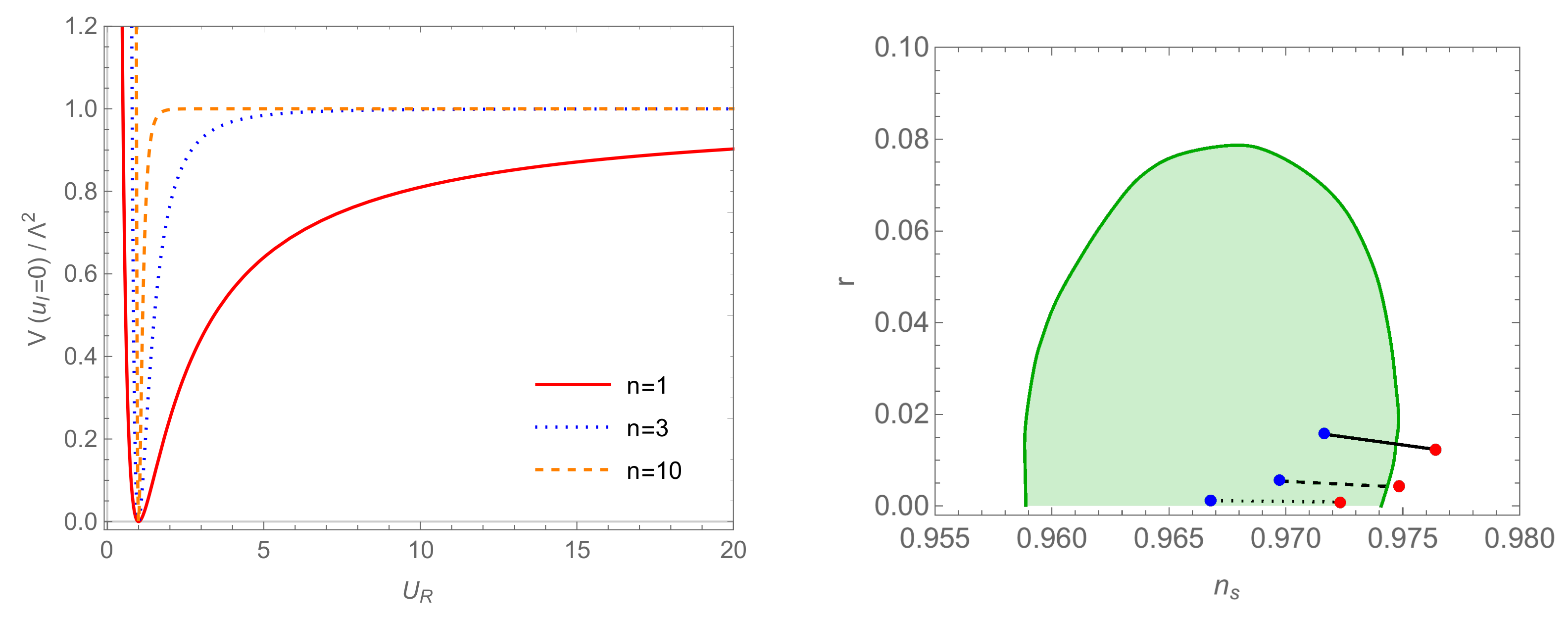

3.5. A Simple Plateau Model

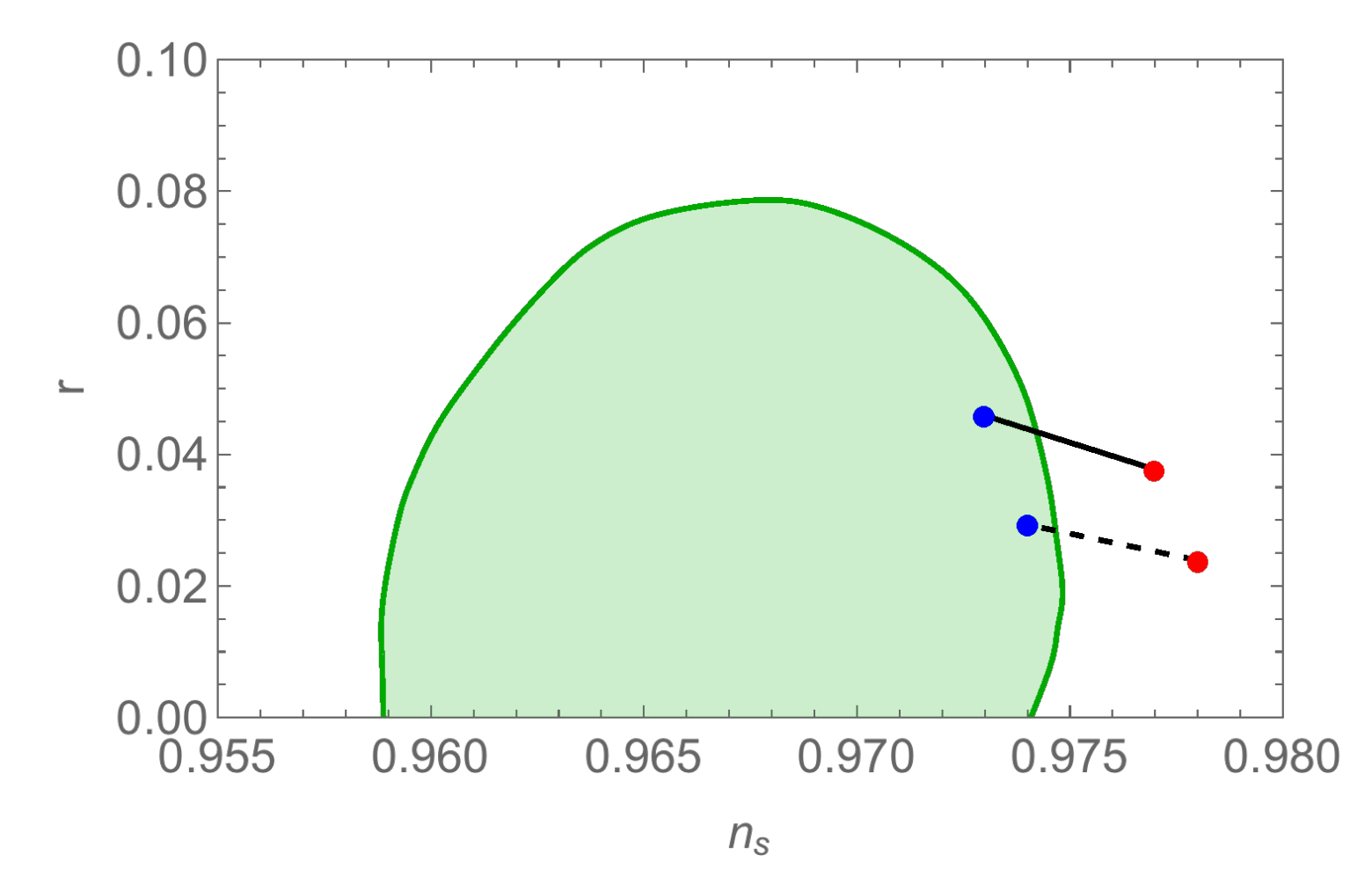

3.6. Plateau from the Modular Transformation

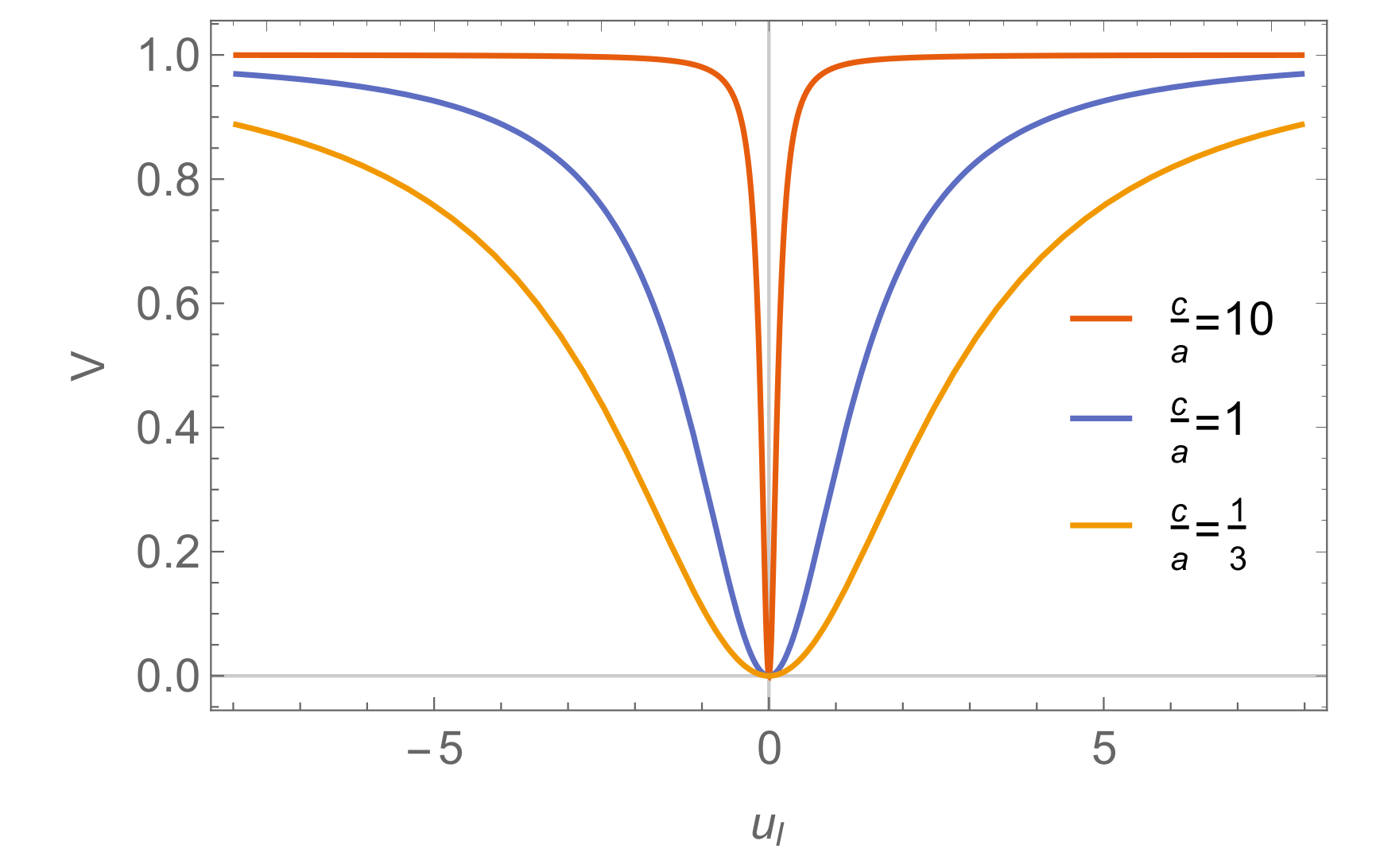

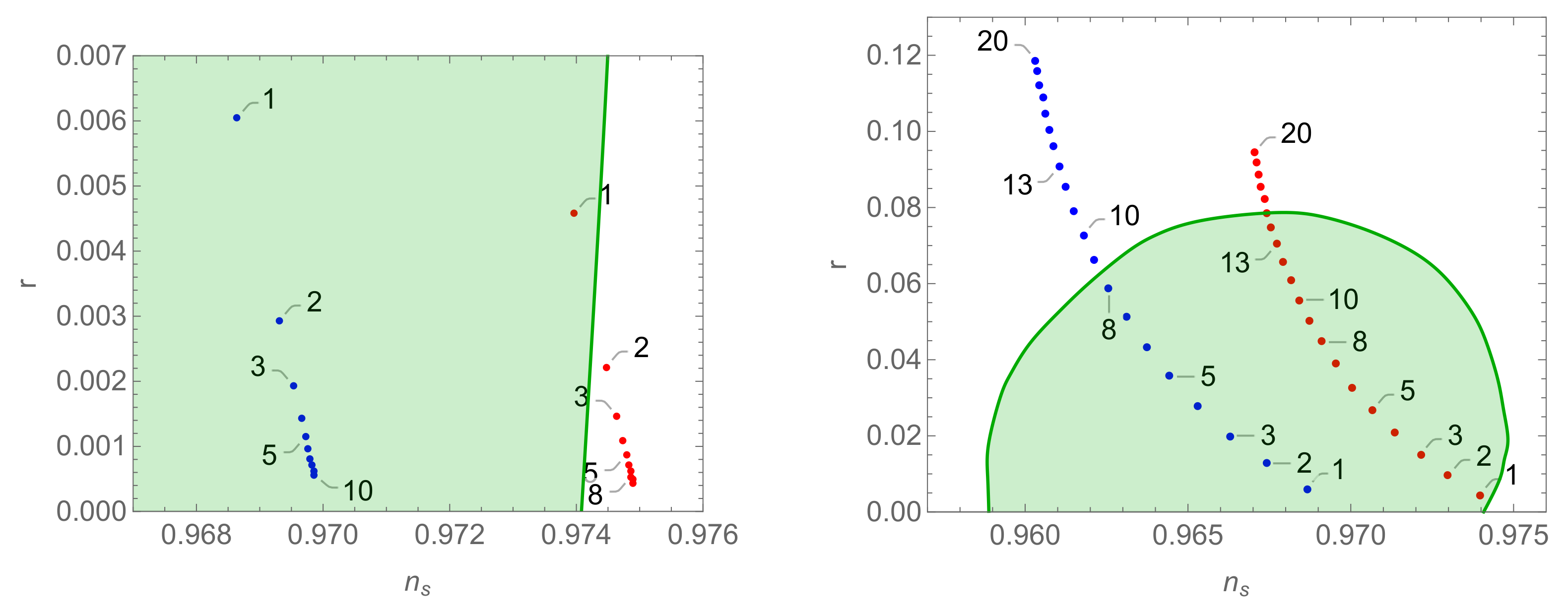

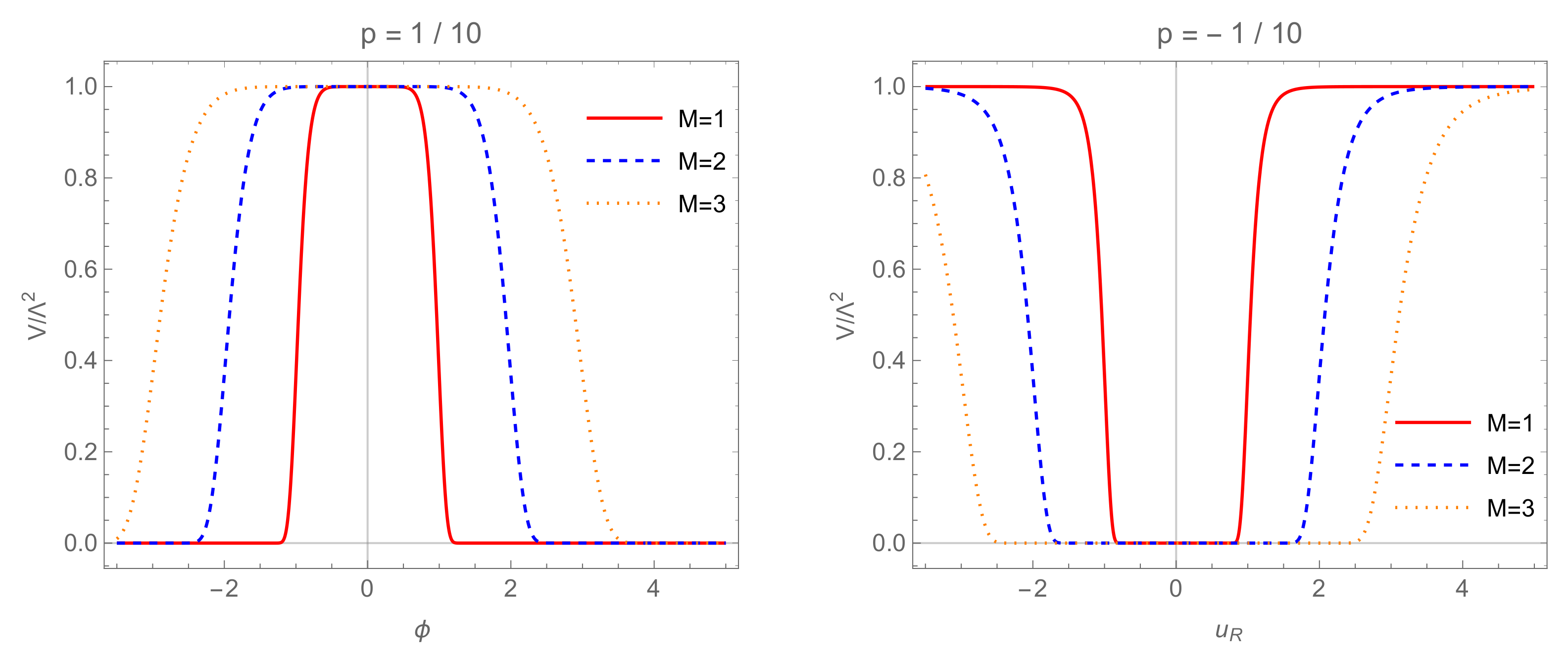

3.7. Bell-Curve Potentials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Starobinsky, A.A. A New Type of Isotropic Cosmological Models Without Singularity. Phys. Lett. 1980, 91, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyth, D.H.; Riotto, A. Particle physics models of inflation and the cosmological density perturbation. Phys. Rep. 1999, 314, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. First Order Phase Transition of a Vacuum and Expansion of the Universe. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 1981, 195, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, A.H. The Inflationary Universe: A Possible Solution to the Horizon and Flatness Problems. Phys. Rev. D 1981, 23, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrami, Y.; Arroja, F.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; et al. Planck 2018 results. X. Constraints on inflation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06211. [Google Scholar]

- Kallosh, R.; Linde, A.; Roest, D. Superconformal Inflationary α-Attractors. JHEP 2013, 1311, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artymowski, M.; Rubio, J. Endlessly flat scalar potentials and α-attractors. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 761, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, K.; Artymowski, M. Initial conditions for inflation. Astropart. Phys. 2017, 94, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Yanagida, T. Natural chaotic inflation in supergravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dayan, I.; Einhorn, M.B. Supergravity Higgs Inflation and Shift Symmetry in Electroweak Theory. JCAP 2010, 1012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K.; Takahashi, F. Higgs Chaotic Inflation in Standard Model and NMSSM. JCAP 2011, 1102, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badziak, M.; Olechowski, M. Volume modulus inflation and a low scale of SUSY breaking. JCAP 2008, 807, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ben-Dayan, I.; Brustein, R.; de Alwis, S.P. Models of Modular Inflation and Their Phenomenological Consequences. JCAP 2008, 807, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covi, L.; Gomez-Reino, M.; Gross, C.; Louis, J.; Palma, G.A.; Scrucca, C.A. Constraints on modular inflation in supergravity and string theory. JHEP 2008, 808, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallosh, R.; Linde, A.; Rube, T. General inflaton potentials in supergravity. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 43507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovik, G.; Zubkov, M. Emergent Weyl spinors in multi-fermion systems. Nucl. Phys. B 2014, 881, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbar, E.; Miransky, V.; Shovkovy, I. Chiral anomaly, dimensional reduction, and magnetoresistivity of Weyl and Dirac semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 85126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrikar, O.; Hughes, T.L.; Leigh, R.G. Torsion, Parity-odd Response and Anomalies in Topological States. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horava, P. Stability of Fermi surfaces and K-theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 16405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovik, G. The Universe in a helium droplet. Int. Ser. Monogr. Phys. 2006, 117, 1–526. [Google Scholar]

- Galante, M.; Kallosh, R.; Linde, A.; Roest, D. Unity of Cosmological Inflation Attractors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 141302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalianis, I.; Watanabe, Y. Probing the BSM physics with CMB precision cosmology: An application to supersymmetry. JHEP 2018, 2, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubekeur, L.; Lyth, D.H. Hilltop inflation. JCAP 2005, 507, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dayan, I.; Jing, S.; Westphal, A.; Wieck, C. Accidental inflation from Kähler uplifting. JCAP 2014, 1403, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dayan, I.; Brustein, R. Cosmic Microwave Background Observables of Small Field Models of Inflation. JCAP 2010, 1009, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhero, T.; Pal, S. Realising Mutated Hilltop Inflation in Supergravity. Phys. Lett. B 2019, 796, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Kawai, H.; Kawana, K. Saddle point inflation in string-inspired theory. PTEP 2015, 2015, 91B01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallosh, R.; Linde, A.; Roest, D. Large field inflation and double α-attractors. JHEP 2014, 1408, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallosh, R.; Linde, A. Superconformal generalizations of the Starobinsky model. JCAP 2013, 1306, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, S.; Ohashi, J.; Kuroyanagi, S.; Felice, A.D. Planck constraints on single-field inflation. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 23529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhero, T. Natural α-Attractors from = 1 Supergravity via flat Kähler Manifolds. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.05406. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, F.C.; Bond, J.R.; Freese, K.; Frieman, J.A.; Olinto, A.V. Natural inflation: Particle physics models, power law spectra for large scale structure, and constraints from COBE. Phys. Rev. D 1993, 47, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhanov, V. Inflation without Selfreproduction. Fortsch. Phys. 2015, 63, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, G.N.; Kofman, L.; Linde, A.D. Instant preheating. Phys. Rev. D 1999, 59, 123523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.H. Gravitational Particle Creation and Inflation. Phys. Rev. D 1987, 35, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artymowski, M.; Czerwinska, O.; Lalak, Z.; Lewicki, M. Gravitational wave signals and cosmological consequences of gravitational reheating. JCAP 2018, 1804, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berera, A.; Brahma, S.; Calderón, J.R. Role of trans-Planckian modes in cosmology. arXiv 2003, arXiv:2003.07184. [Google Scholar]

- Brahma, S. Trans-Planckian censorship conjecture from the swampland distance conjecture. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 46013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Wang, S. A refined trans-Planckian censorship conjecture. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00607. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dayan, I. Draining the Swampland. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Artymowski, M.; Ben-Dayan, I. Inflation in Supergravity from Field Redefinitions. Symmetry 2020, 12, 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050806

Artymowski M, Ben-Dayan I. Inflation in Supergravity from Field Redefinitions. Symmetry. 2020; 12(5):806. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050806

Chicago/Turabian StyleArtymowski, Michał, and Ido Ben-Dayan. 2020. "Inflation in Supergravity from Field Redefinitions" Symmetry 12, no. 5: 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050806

APA StyleArtymowski, M., & Ben-Dayan, I. (2020). Inflation in Supergravity from Field Redefinitions. Symmetry, 12(5), 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050806