Numerical Simulation of Pattern Formation on Surfaces Using an Efficient Linear Second-Order Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Swift–Hohenberg Type of Equation on a Narrow Band Domain

3. Numerical Method

4. Numerical Experiments

4.1. Convergence Test

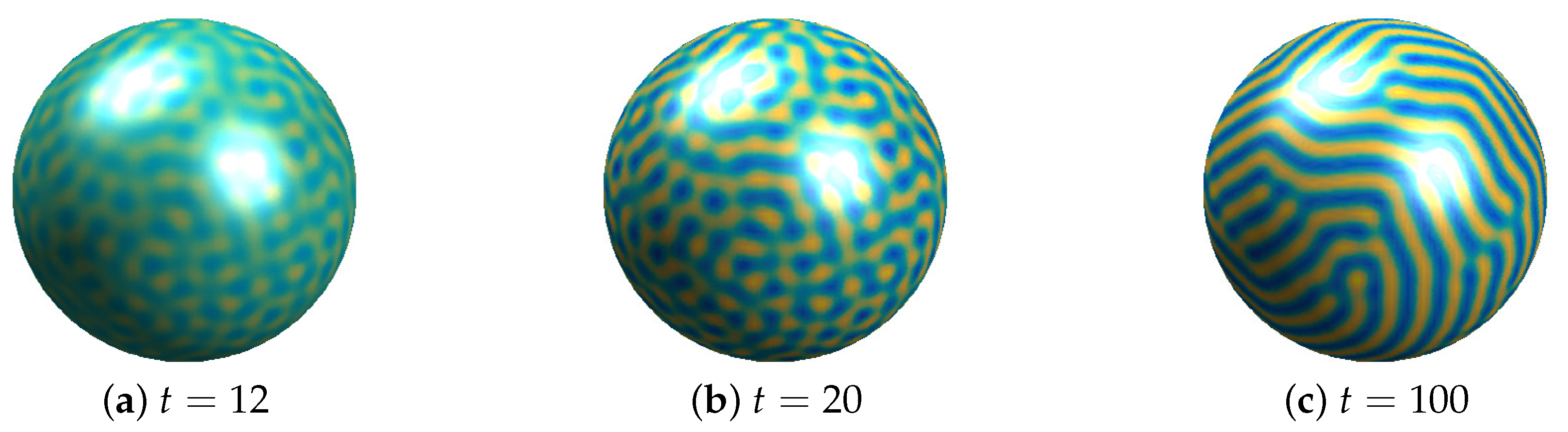

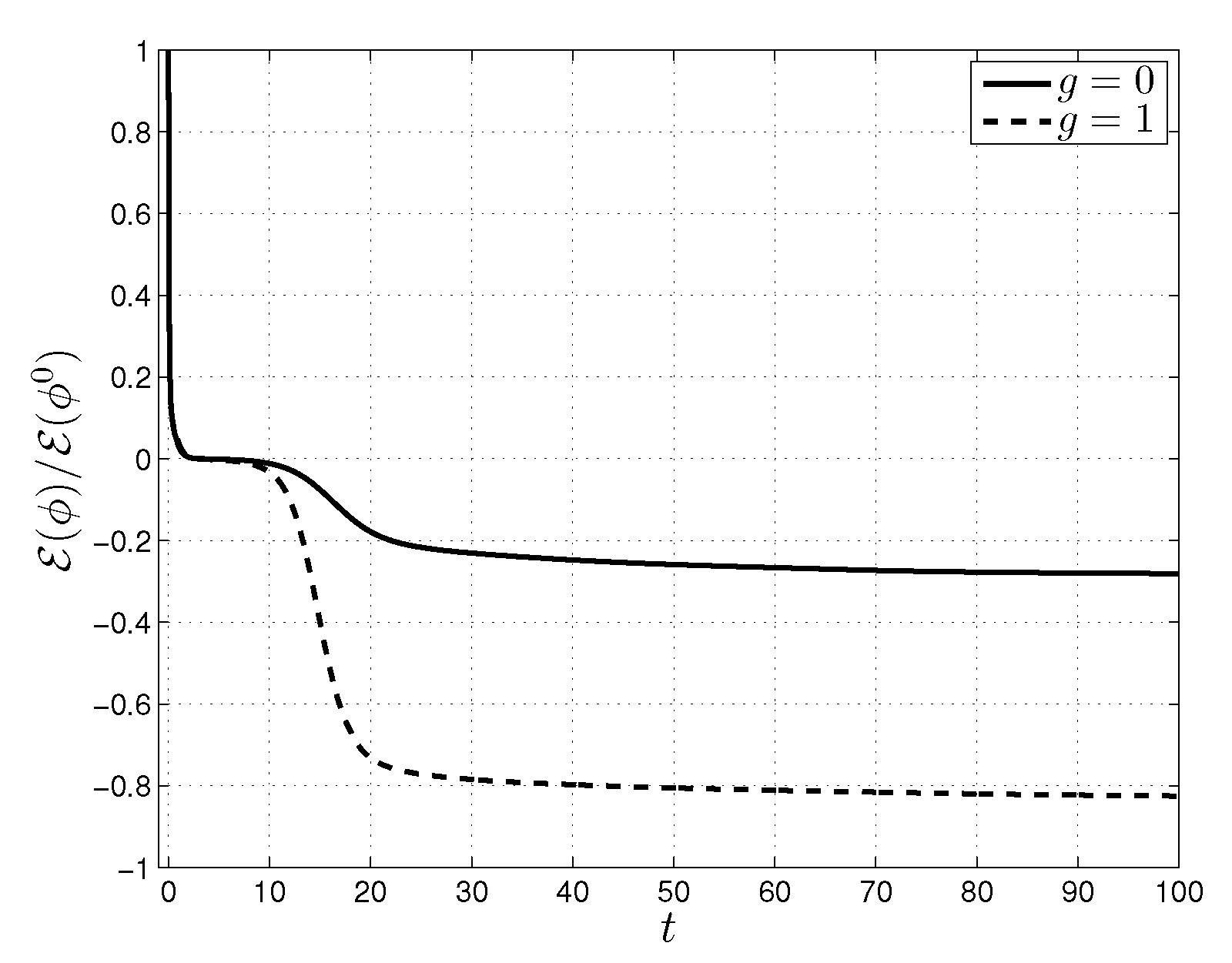

4.2. Pattern Formation on a Sphere

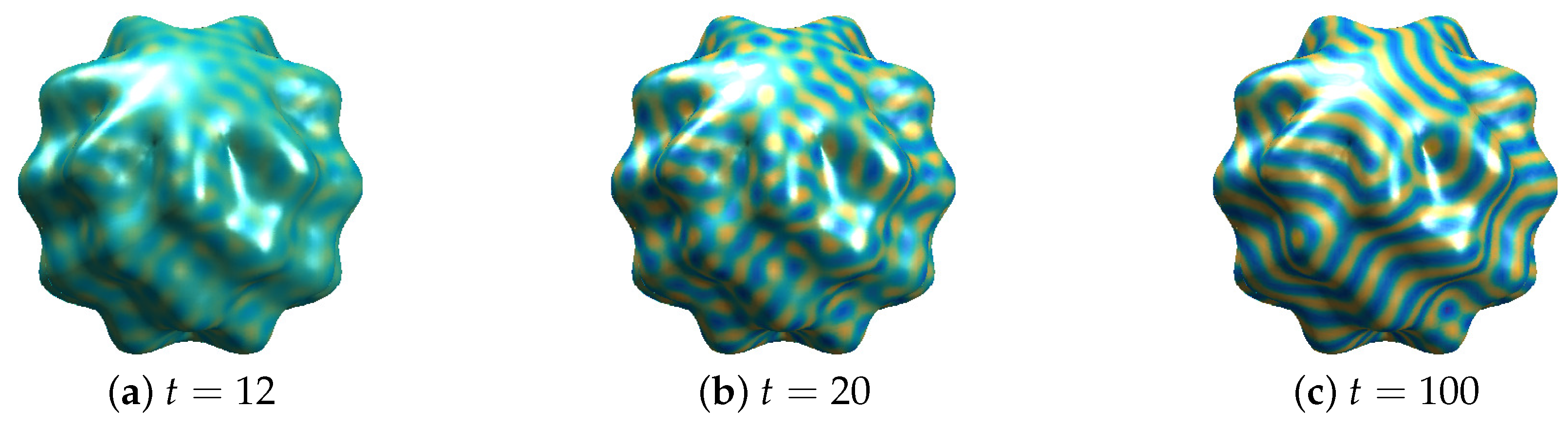

4.3. Pattern Formation on a Sphere Perturbed by a Spherical Harmonic

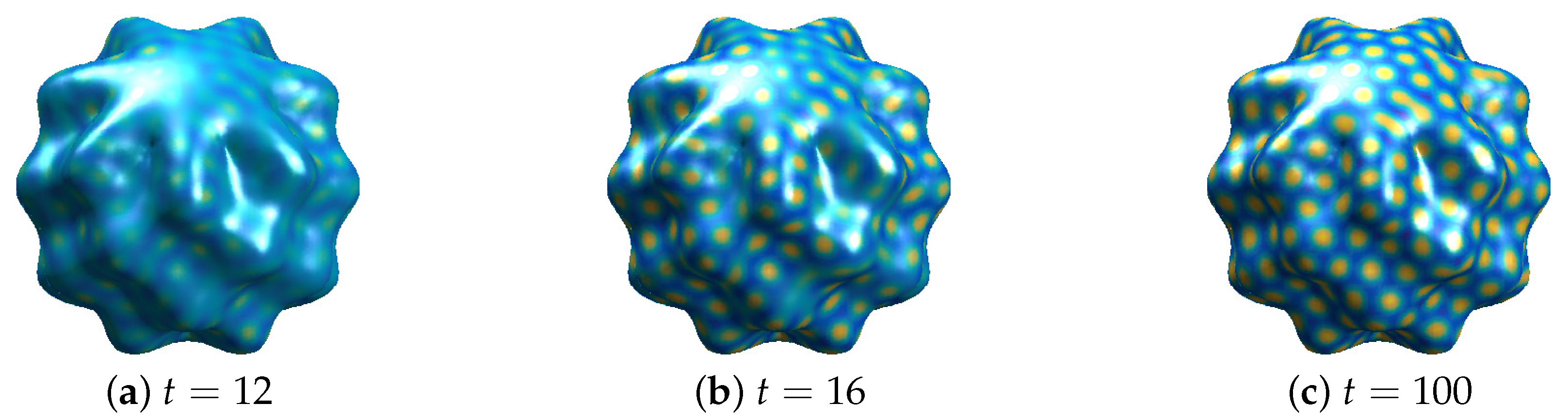

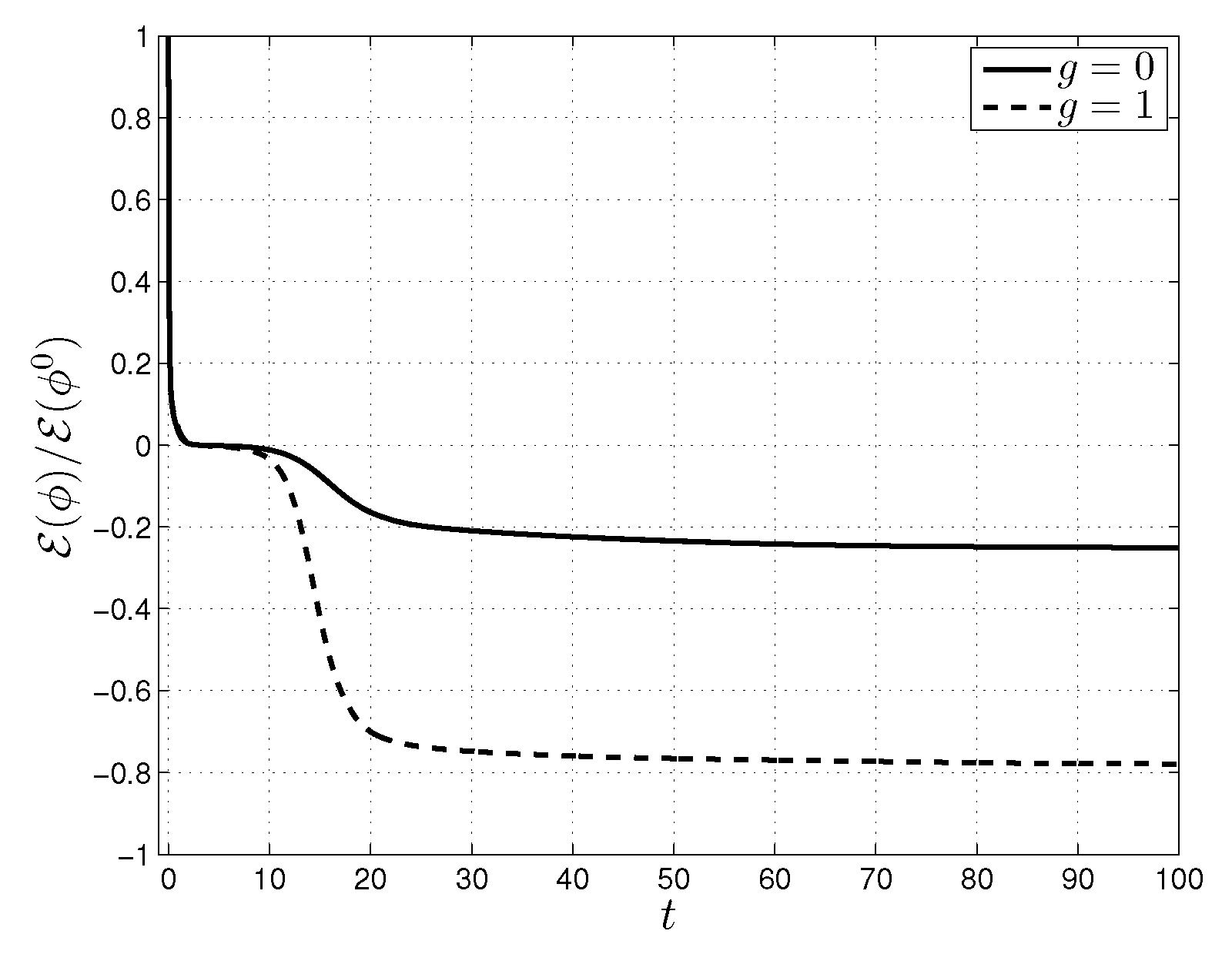

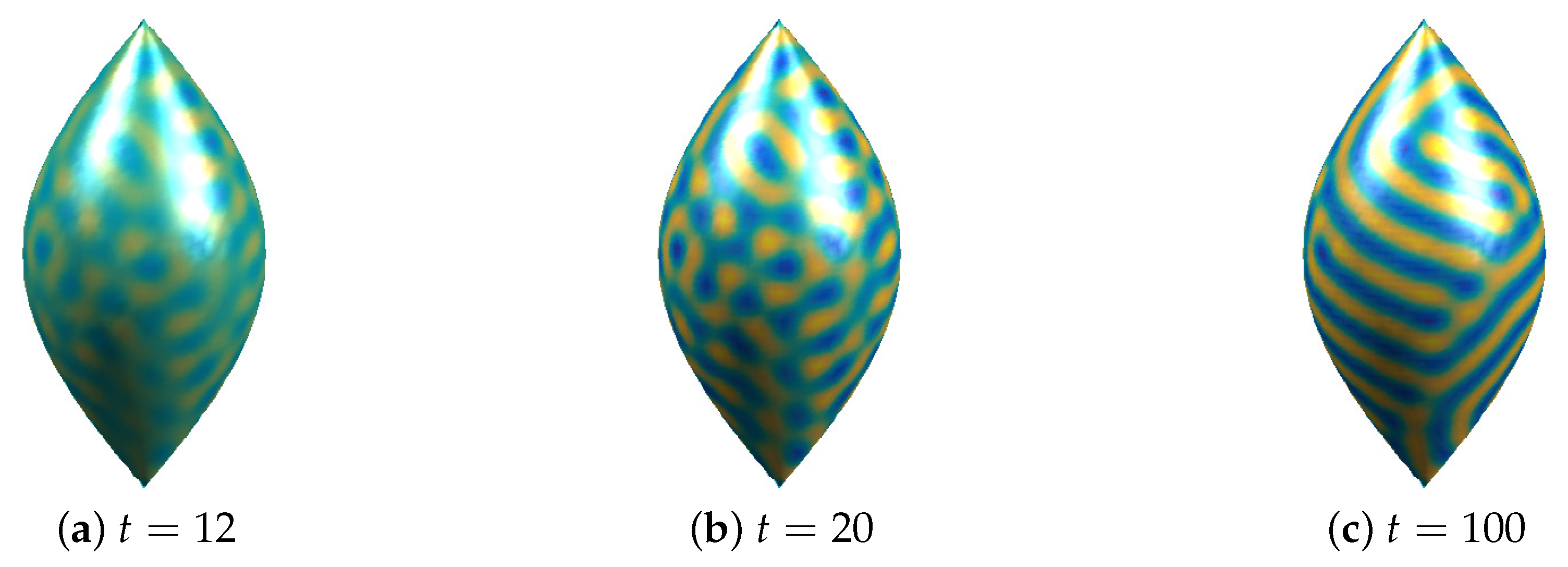

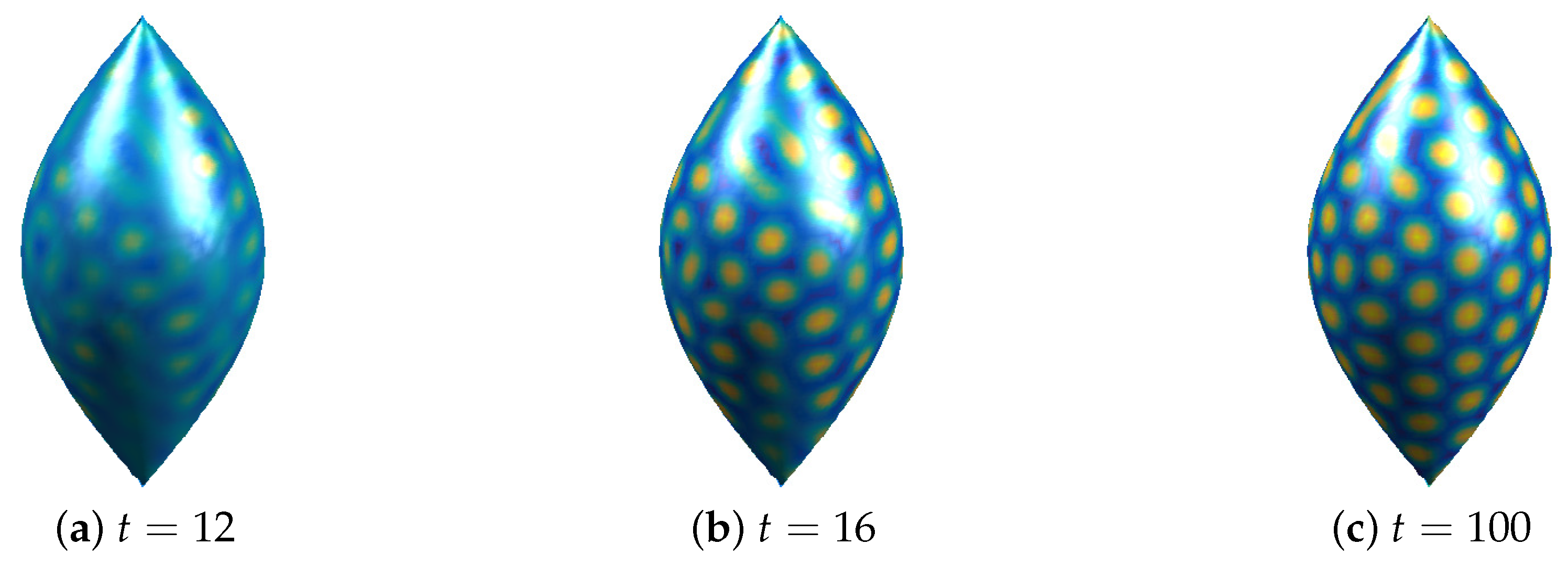

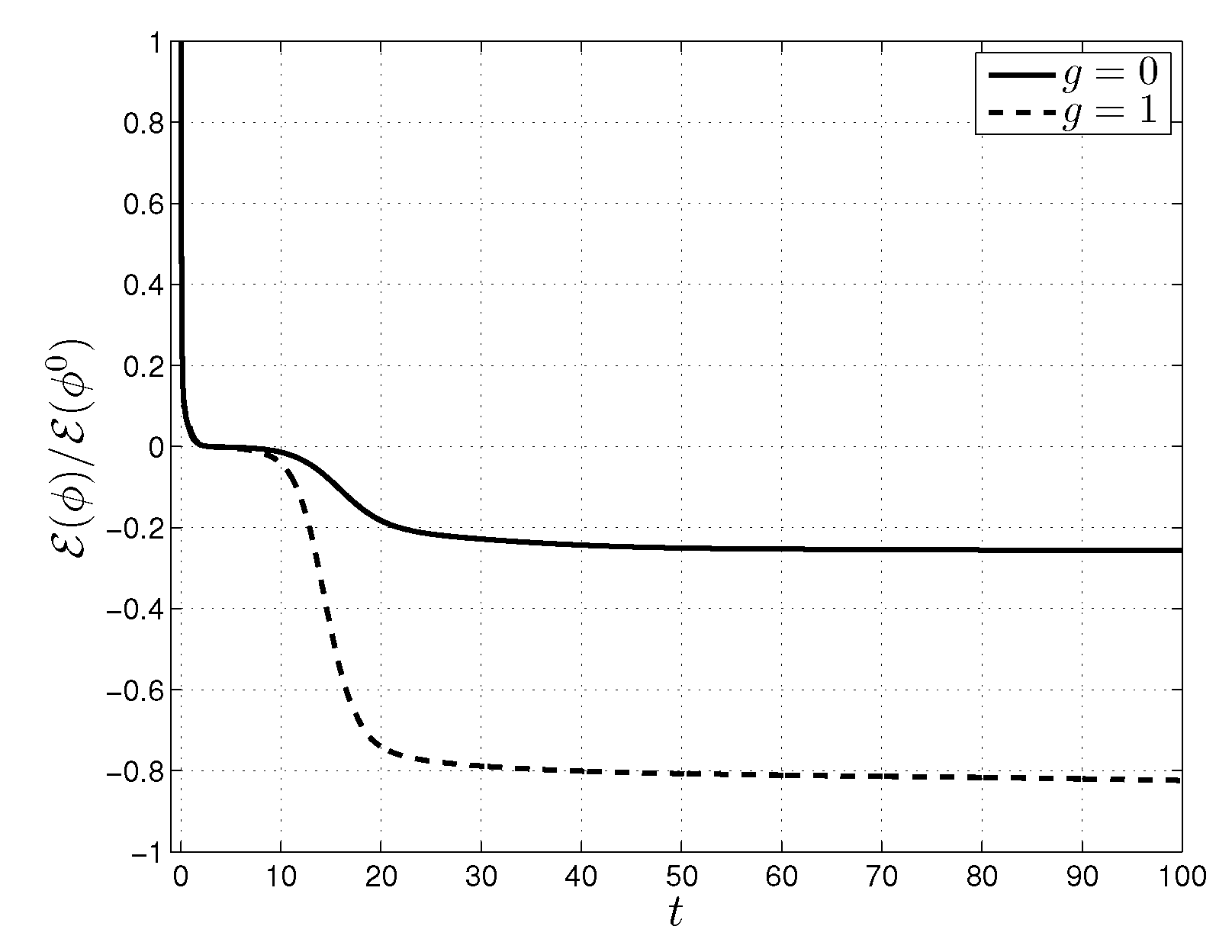

4.4. Pattern Formation on a Spindle

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swift, J.; Hohenberg, P.C. Hydrodynamic fluctuations at the convective instability. Phys. Rev. A 1977, 15, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.C.; Swift, J.B. Effects of additive noise at the onset of Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 46, 4773–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, M.C.; Hohenberg, P.C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1993, 65, 851–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.R.; Pontes, J.; Christov, C.I.; Ramos, F.M.; Rodrigues Neto, C.; Rempel, E.L.; Walgraef, D. Gradient pattern analysis of Swift–Hohenberg dynamics: Phase disorder characterization. Phys. A 2000, 283, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutt, A.; Atay, F.M. Analysis of nonlocal neural fields for both general and gamma-distributed connectivities. Phys. D 2005, 203, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Warren, J.A. An efficient algorithm for solving the phase field crystal model. J. Comput. Phys. 2008, 227, 6241–6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, S.M.; Wang, C.; Lowengrub, J.S. An energy-stable and convergent finite-difference scheme for the phase field crystal equation. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2009, 47, 2269–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, H.; Nogueira, X. A new space–time discretization for the Swift–Hohenberg equation that strictly respects the Lyapunov functional. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2012, 17, 4930–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsey, M.; Wirth, B. A simple and efficient scheme for phase field crystal simulation. ESAIM: Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2013, 47, 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.F.; Espath, L.F.R.; Vignal, P.; Dalcin, L.; Parsani, M.; Calo, V.M. An energy-stable generalized-α method for the Swift–Hohenberg equation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 344, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G. An energy stable method for the Swift–Hohenberg equation with quadratic–cubic nonlinearity. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 343, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, P.C. Pattern formation on a sphere. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 67, 036206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigrist, R.; Matthews, P. Symmetric spiral patterns on spheres. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 2011, 10, 1177–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruuth, S.J.; Merriman, B. A simple embedding method for solving partial differential equations on surfaces. J. Comput. Phys. 2008, 227, 1943–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Jeong, D.; Lee, S.; Yoo, M.; Kim, J. Motion by mean curvature of curves on surfaces using the Allen–Cahn equation. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2015, 97, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Kim, J. A simple and efficient finite difference method for the phase-field crystal equation on curved surfaces. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 307, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Han, C.; Hong, W.-T. Iterative speedup by utilizing symmetric data in pricing options with two risky assets. Symmetry 2017, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, C.; Tang, Y.; Cho, Y.J. Convergence analysis of an inexact three-operator splitting algorithm. Symmetry 2018, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertalmío, M.; Cheng, L.-T.; Osher, S.; Sapiro, G. Variational problems and partial differential equations on implicit surfaces. J. Comput. Phys. 2001, 174, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, J.B. An improvement of a recent Eulerian method for solving PDEs on general geometries. J. Sci. Comput. 2006, 29, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, G. On the construction and comparison of difference schemes. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1968, 5, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| -error | |||||||

| Rate | 2.02 | 2.22 | 2.37 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.G. Numerical Simulation of Pattern Formation on Surfaces Using an Efficient Linear Second-Order Method. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11081010

Lee HG. Numerical Simulation of Pattern Formation on Surfaces Using an Efficient Linear Second-Order Method. Symmetry. 2019; 11(8):1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11081010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyun Geun. 2019. "Numerical Simulation of Pattern Formation on Surfaces Using an Efficient Linear Second-Order Method" Symmetry 11, no. 8: 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11081010

APA StyleLee, H. G. (2019). Numerical Simulation of Pattern Formation on Surfaces Using an Efficient Linear Second-Order Method. Symmetry, 11(8), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11081010