LocPass: A Graphical Password Method to Prevent Shoulder-Surfing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Proposed Method

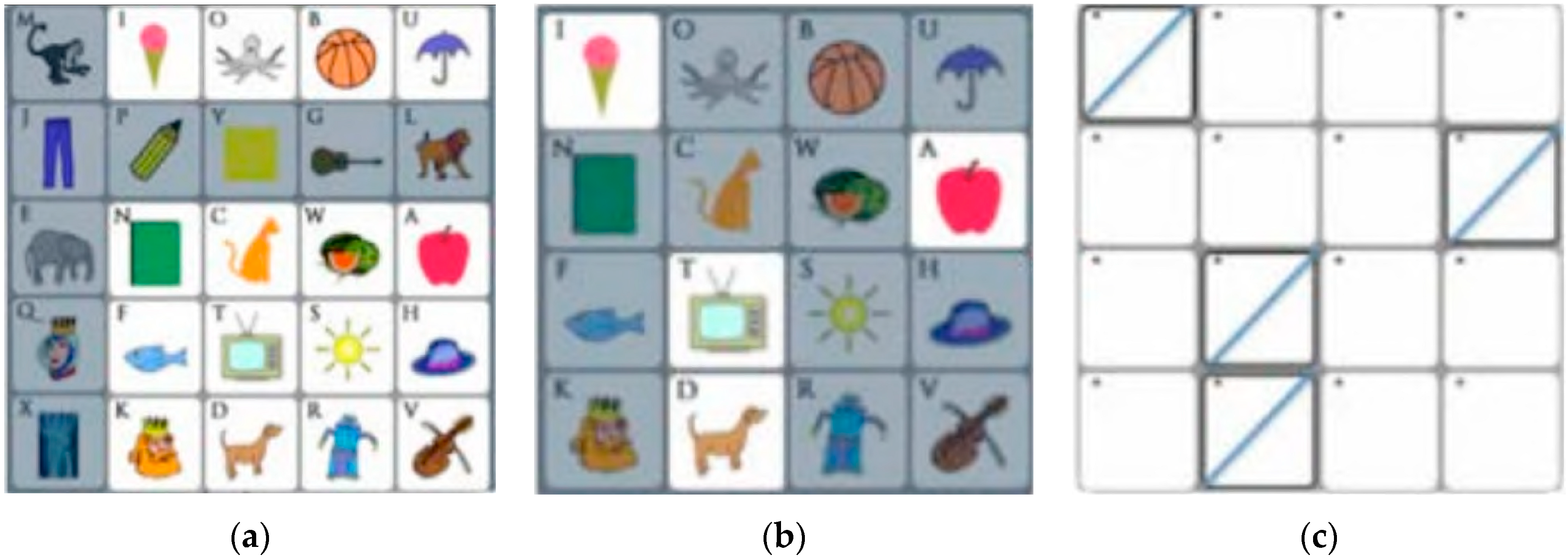

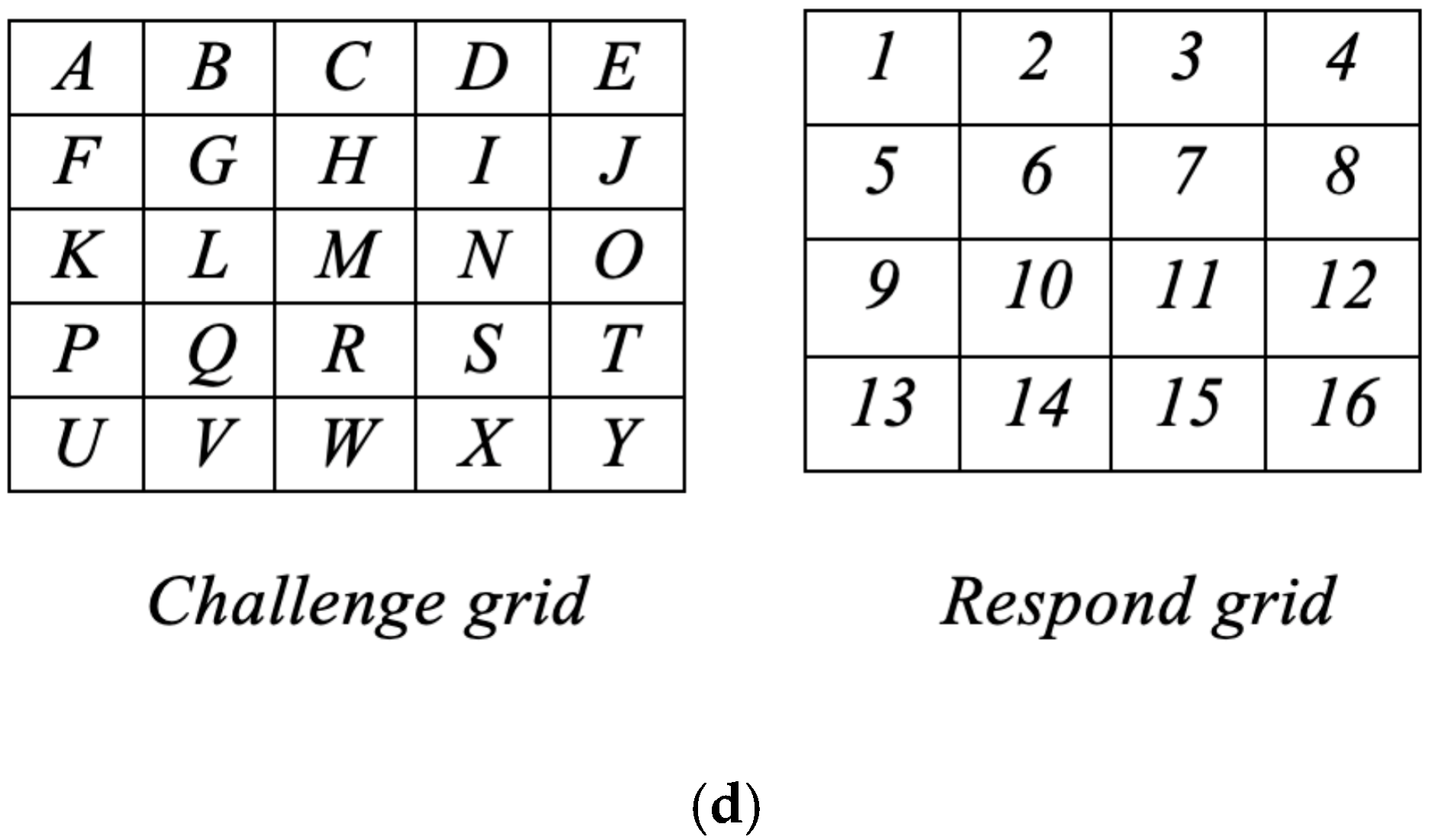

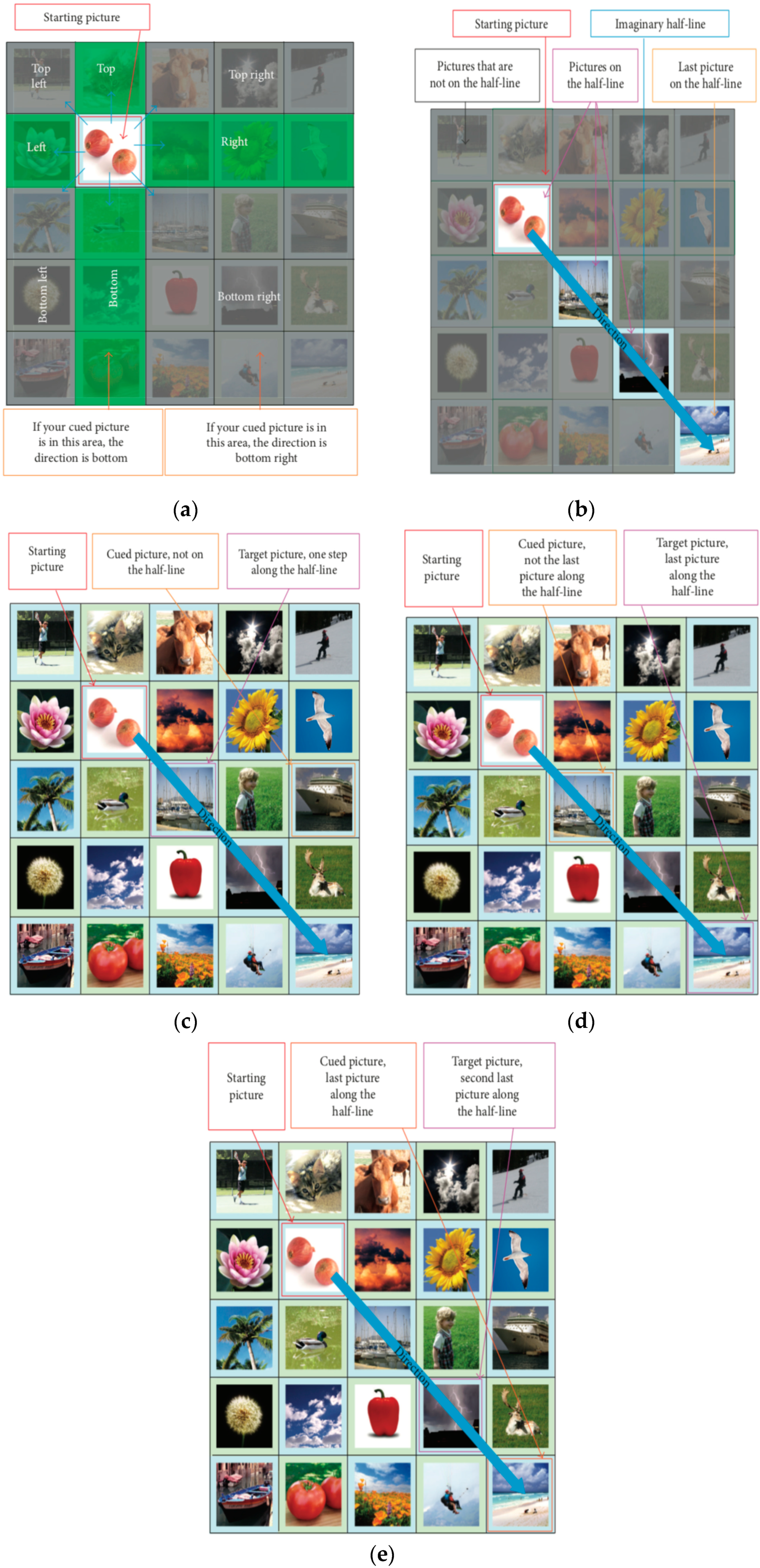

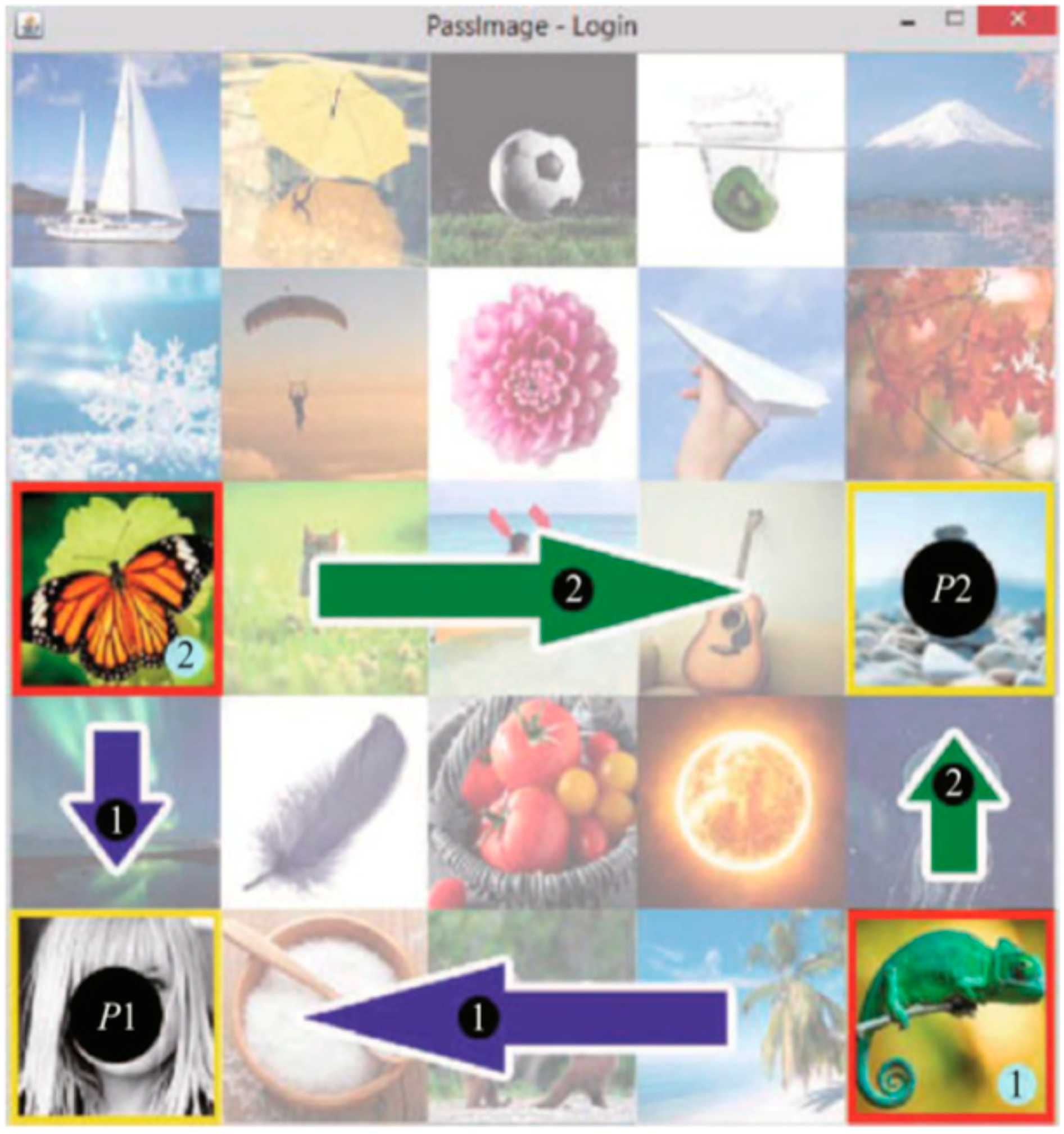

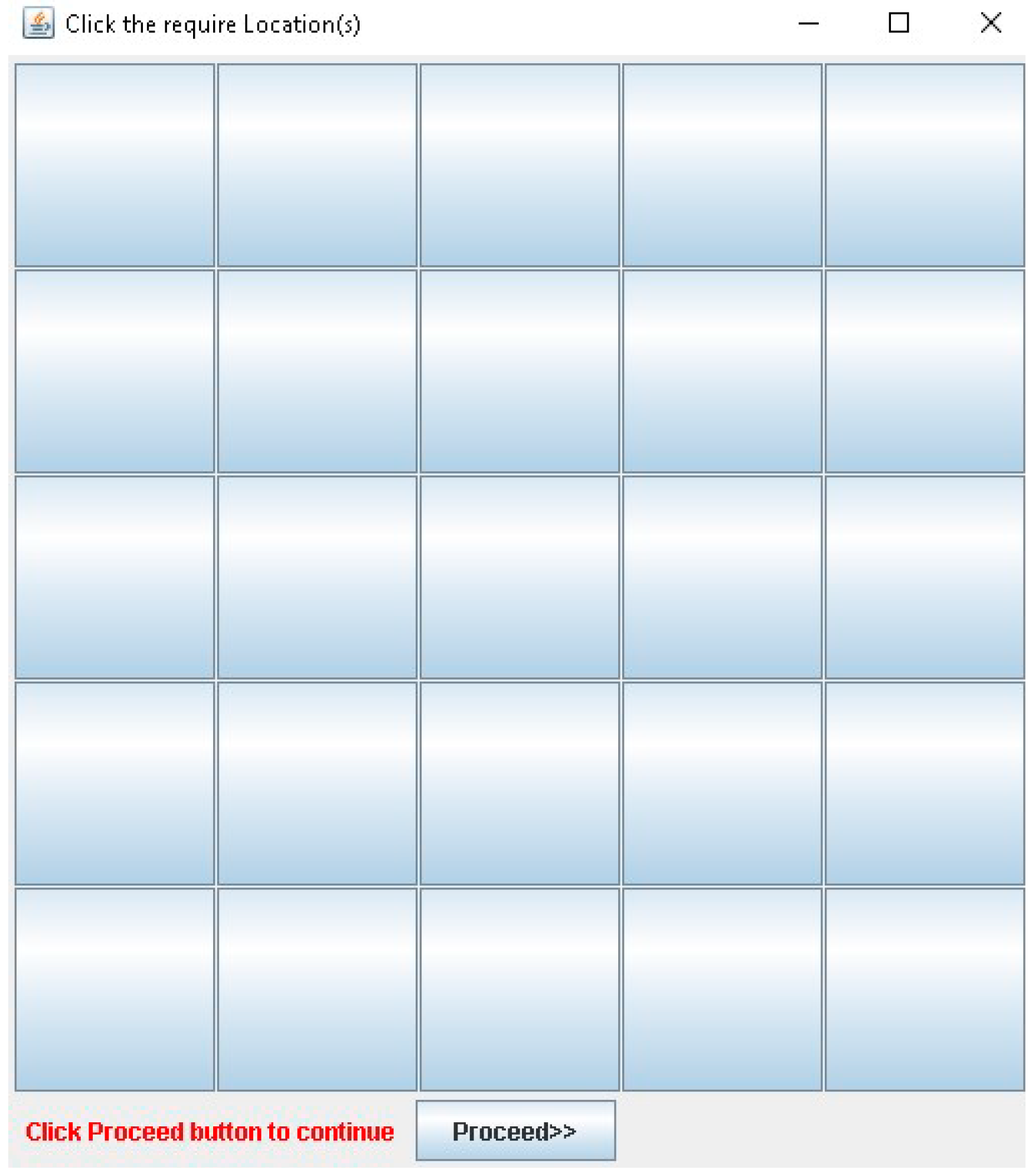

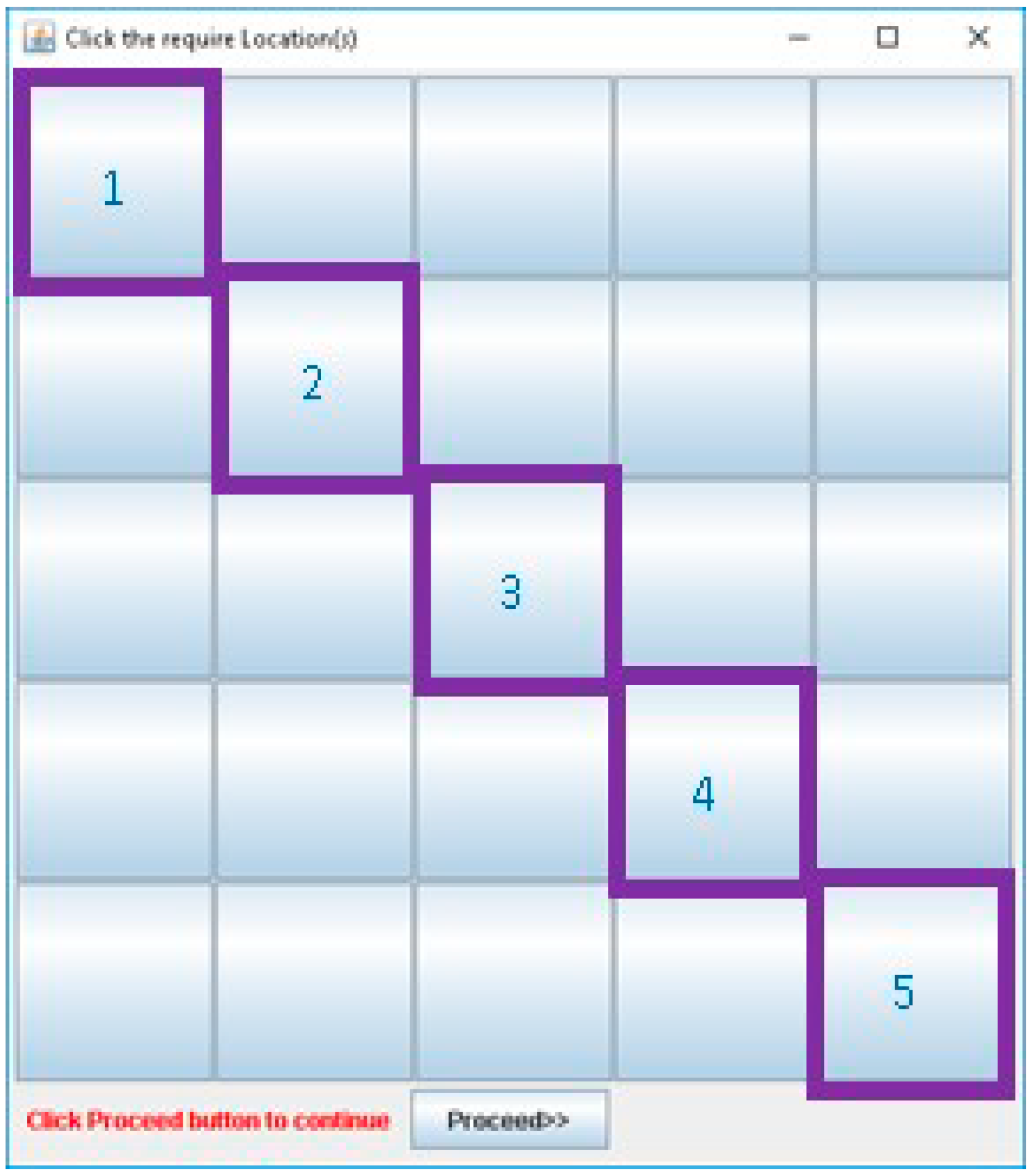

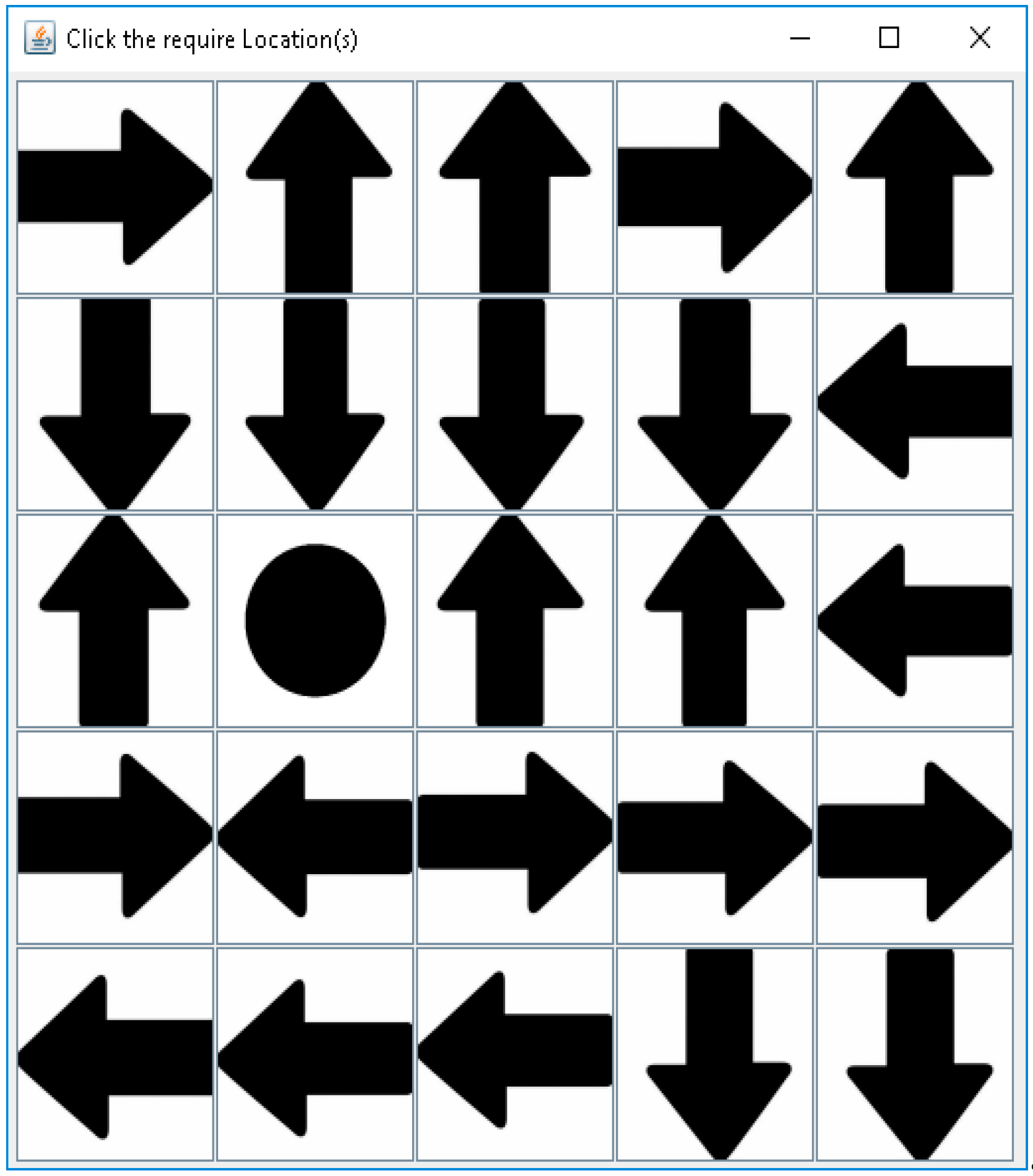

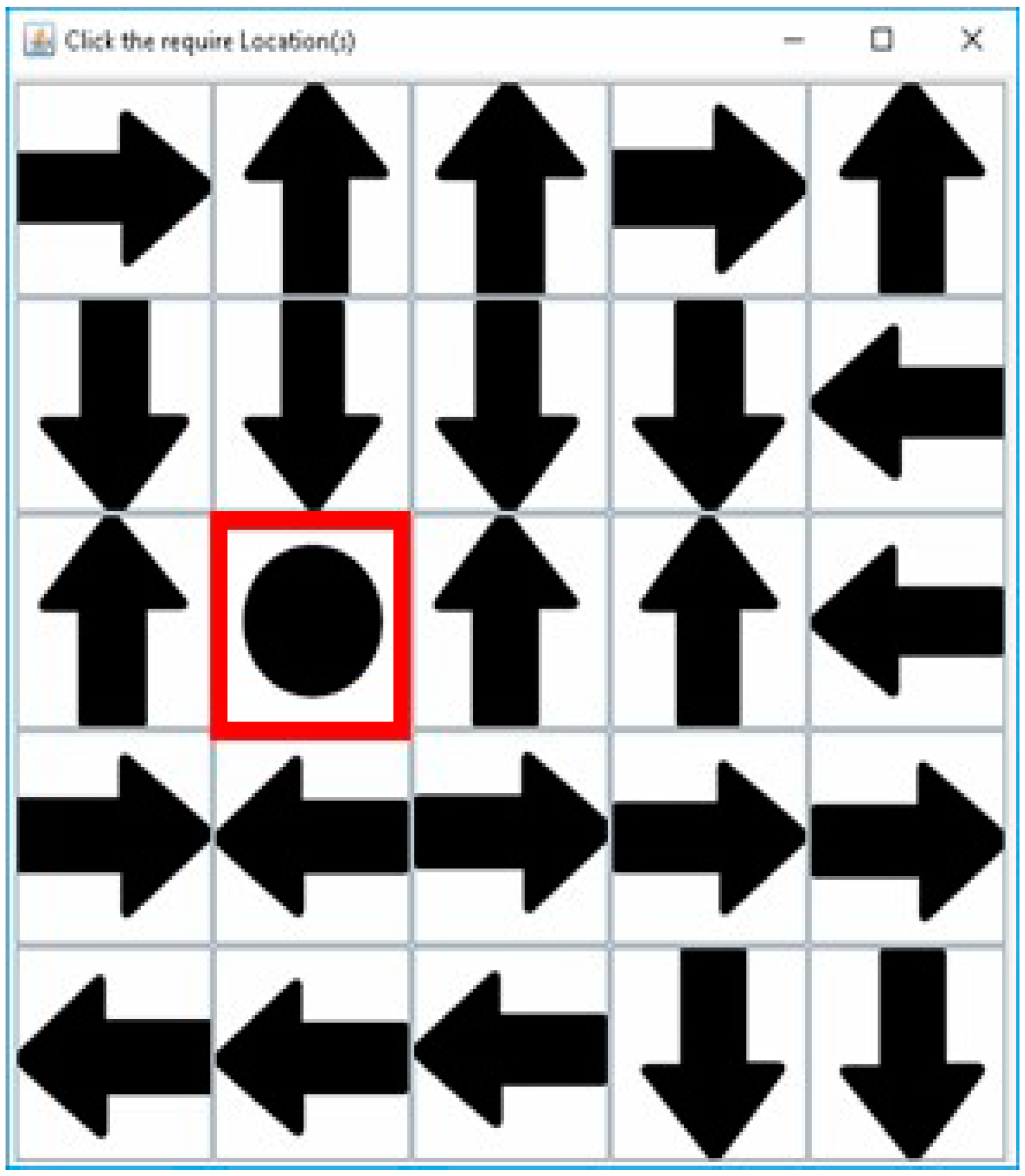

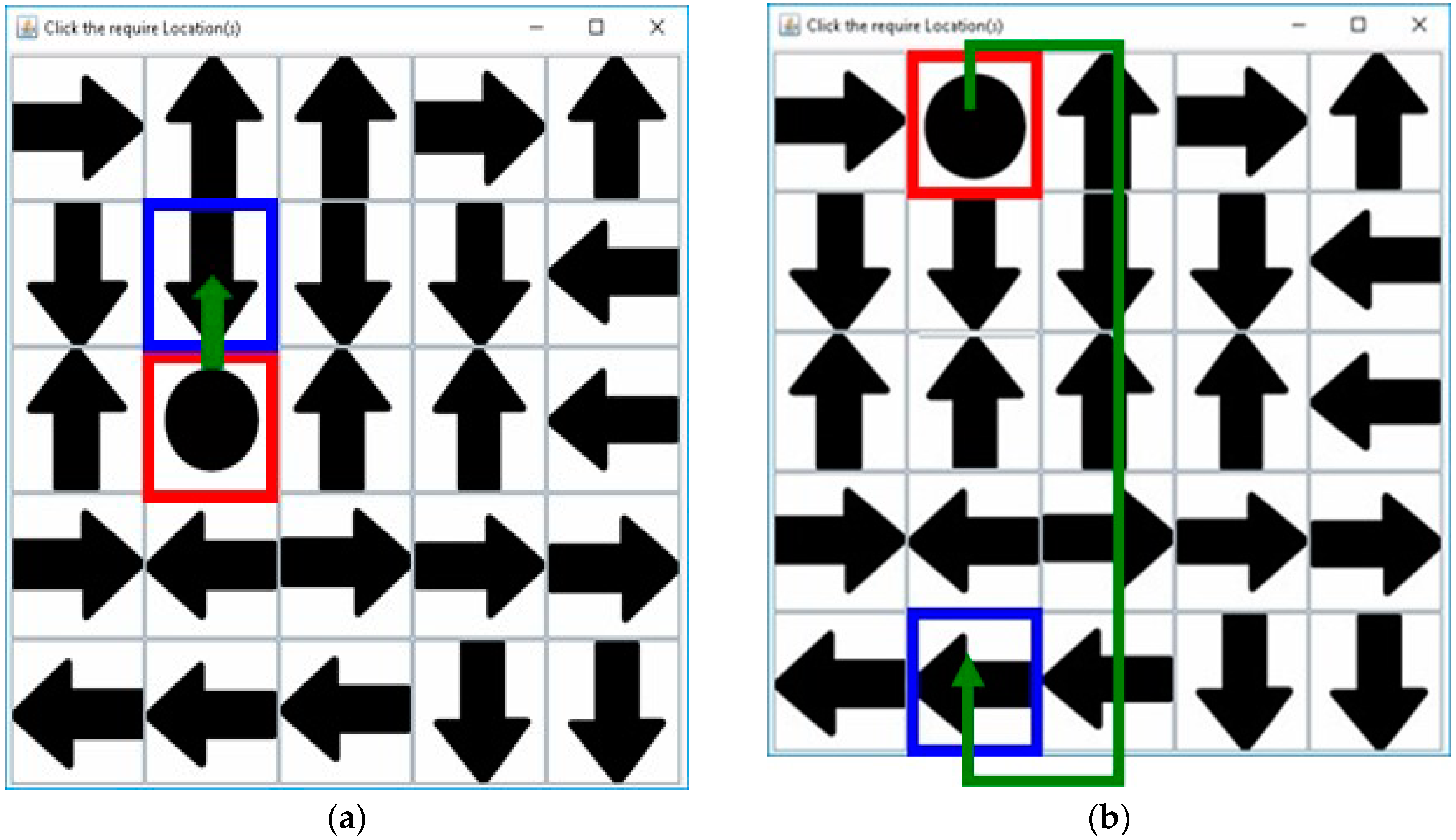

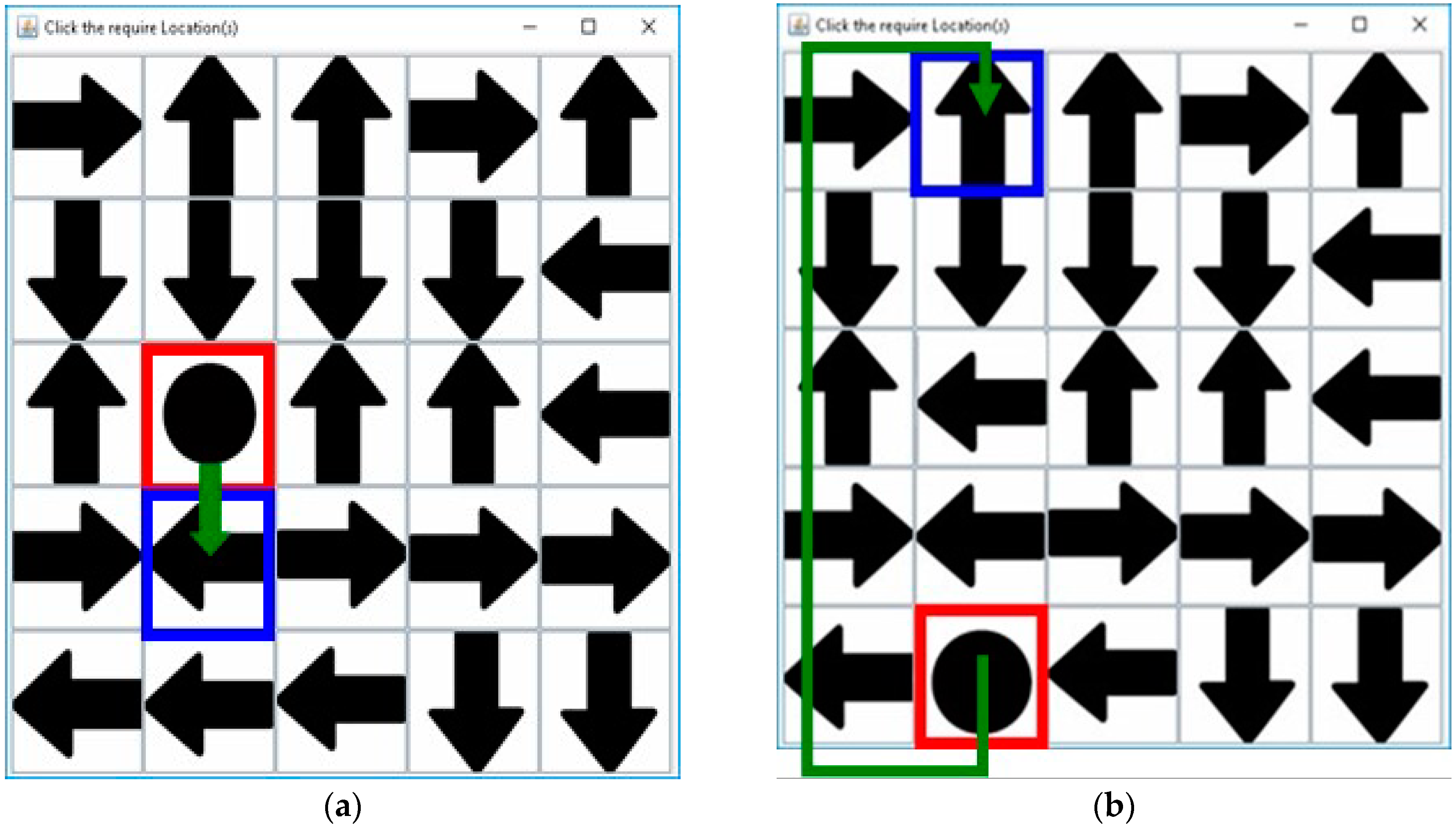

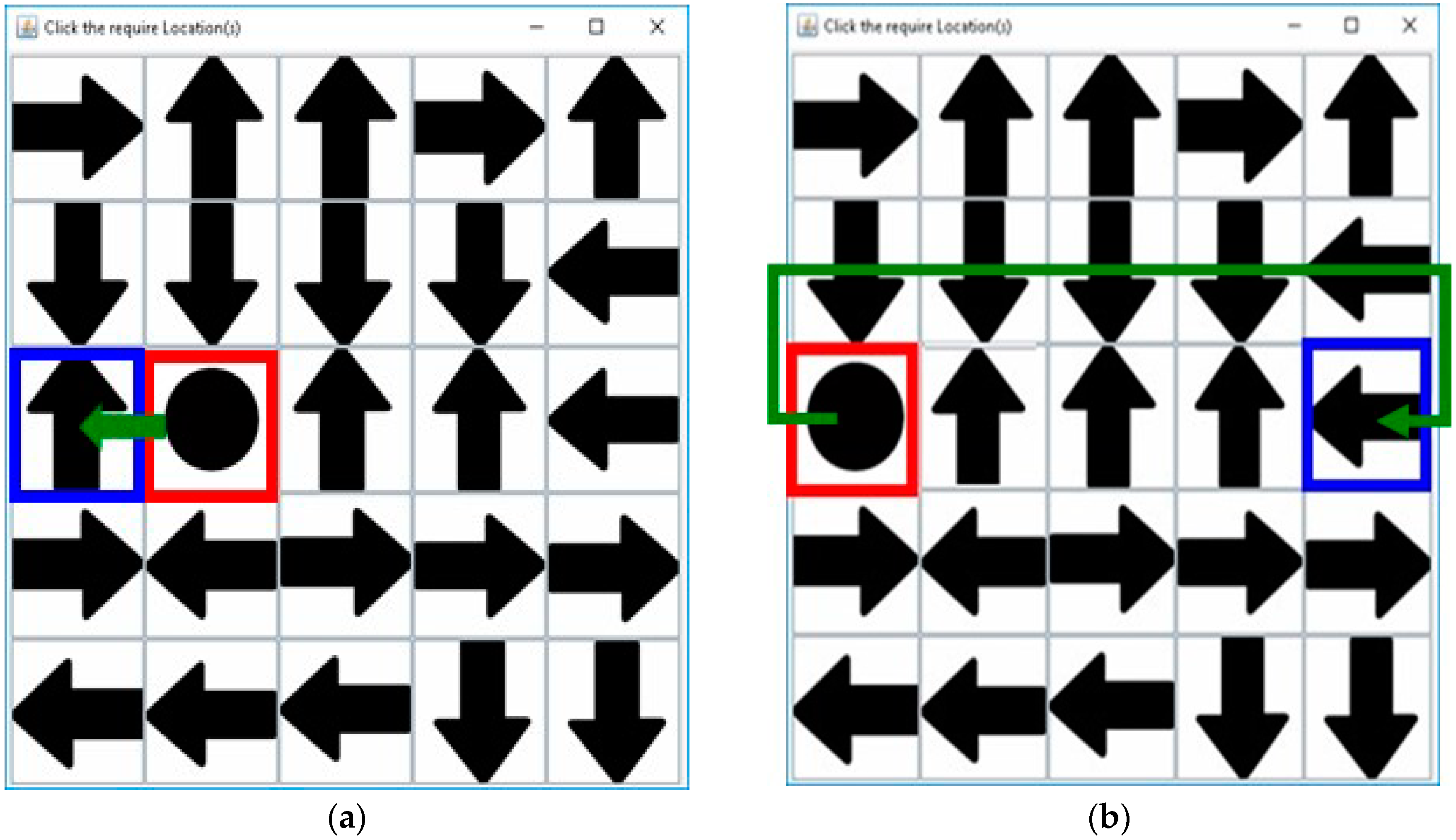

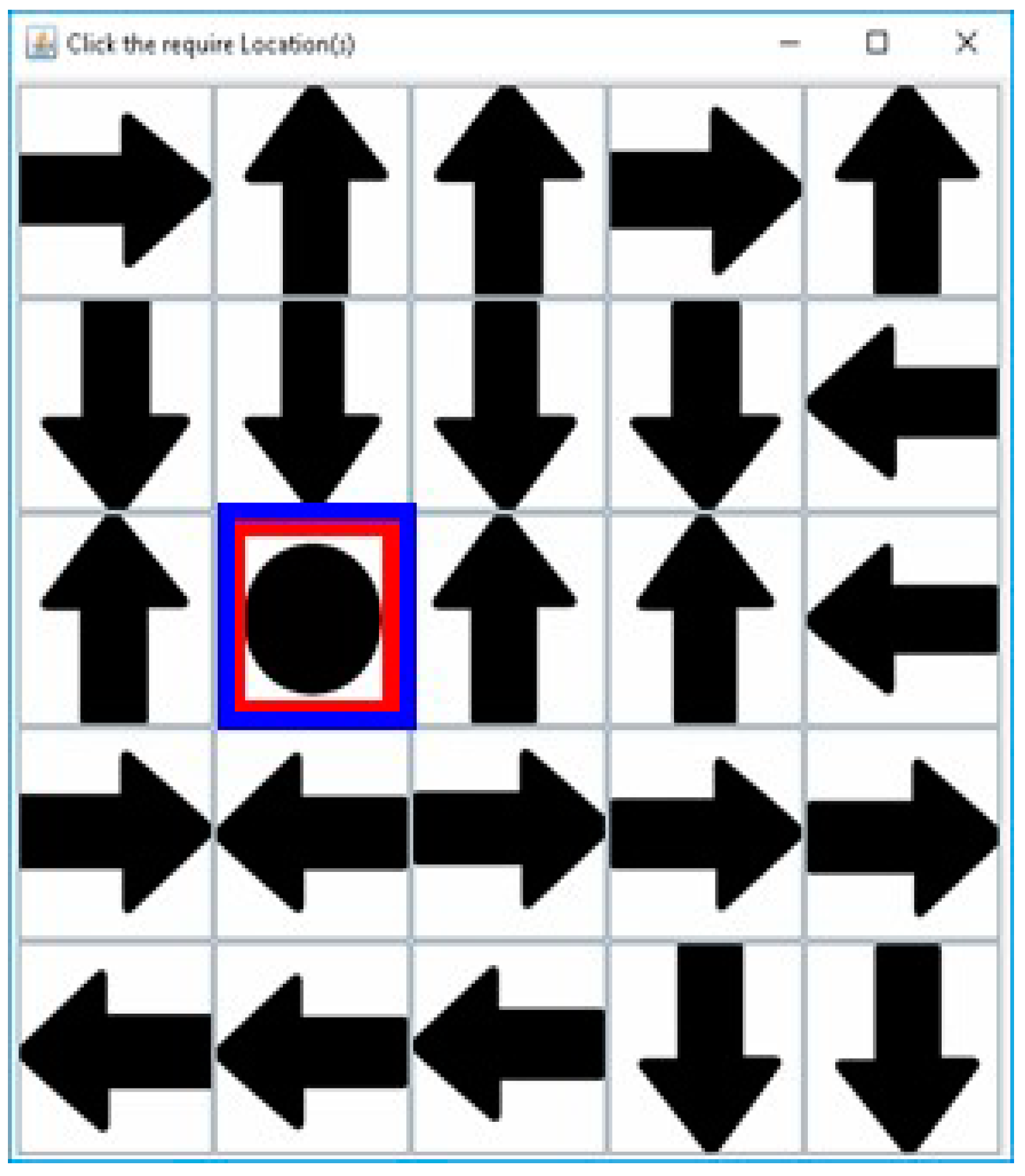

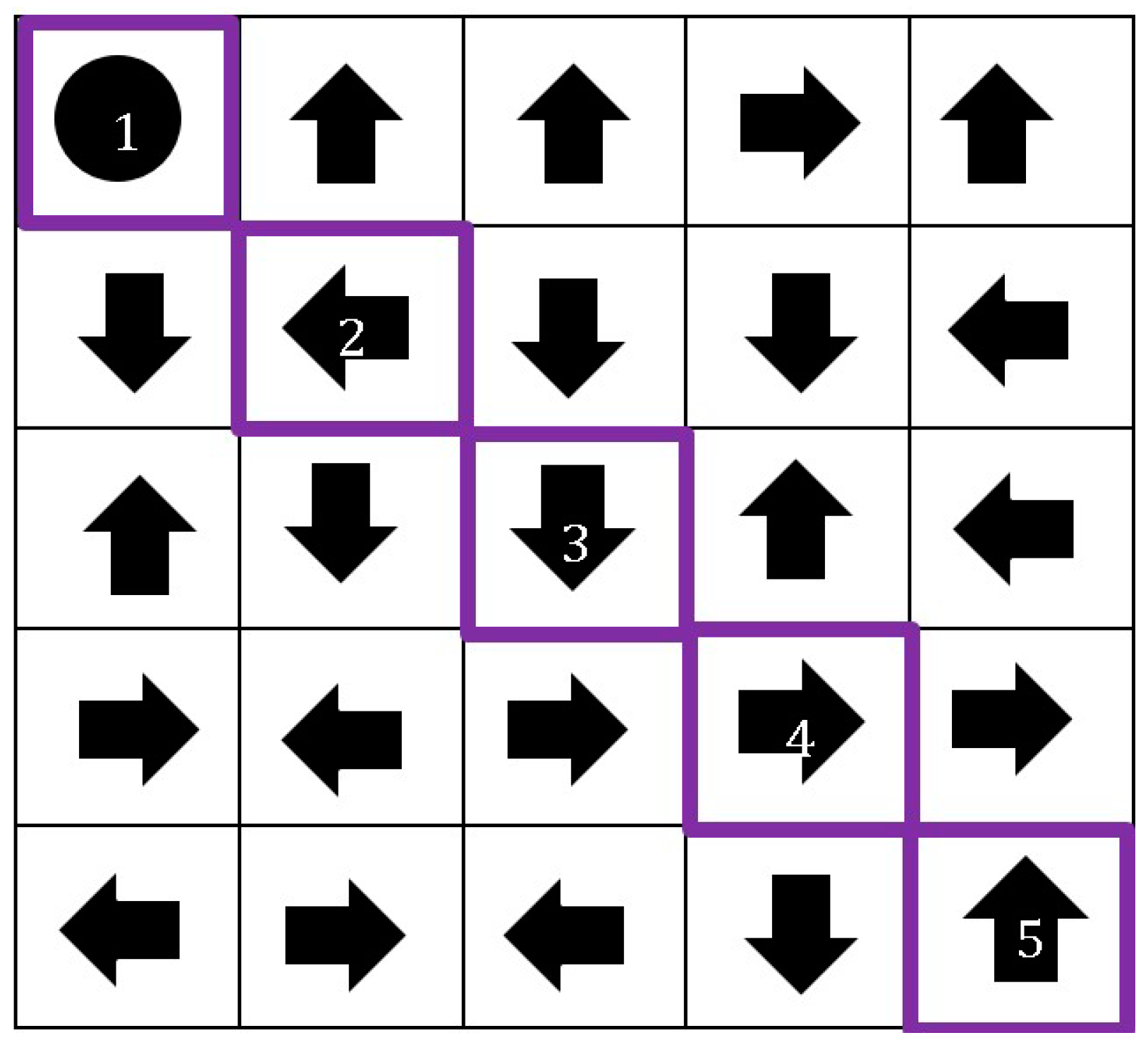

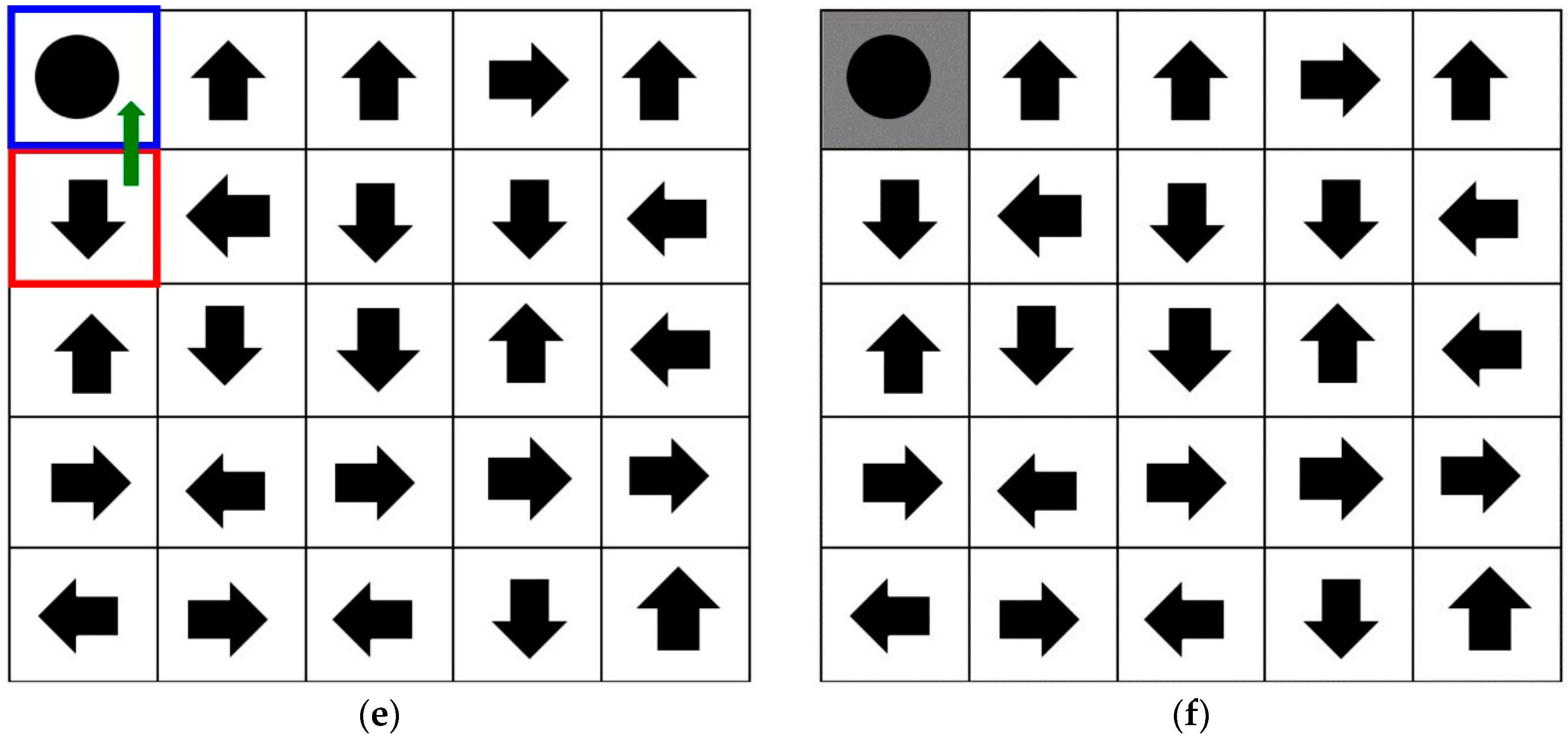

3.1. Registration Procedure

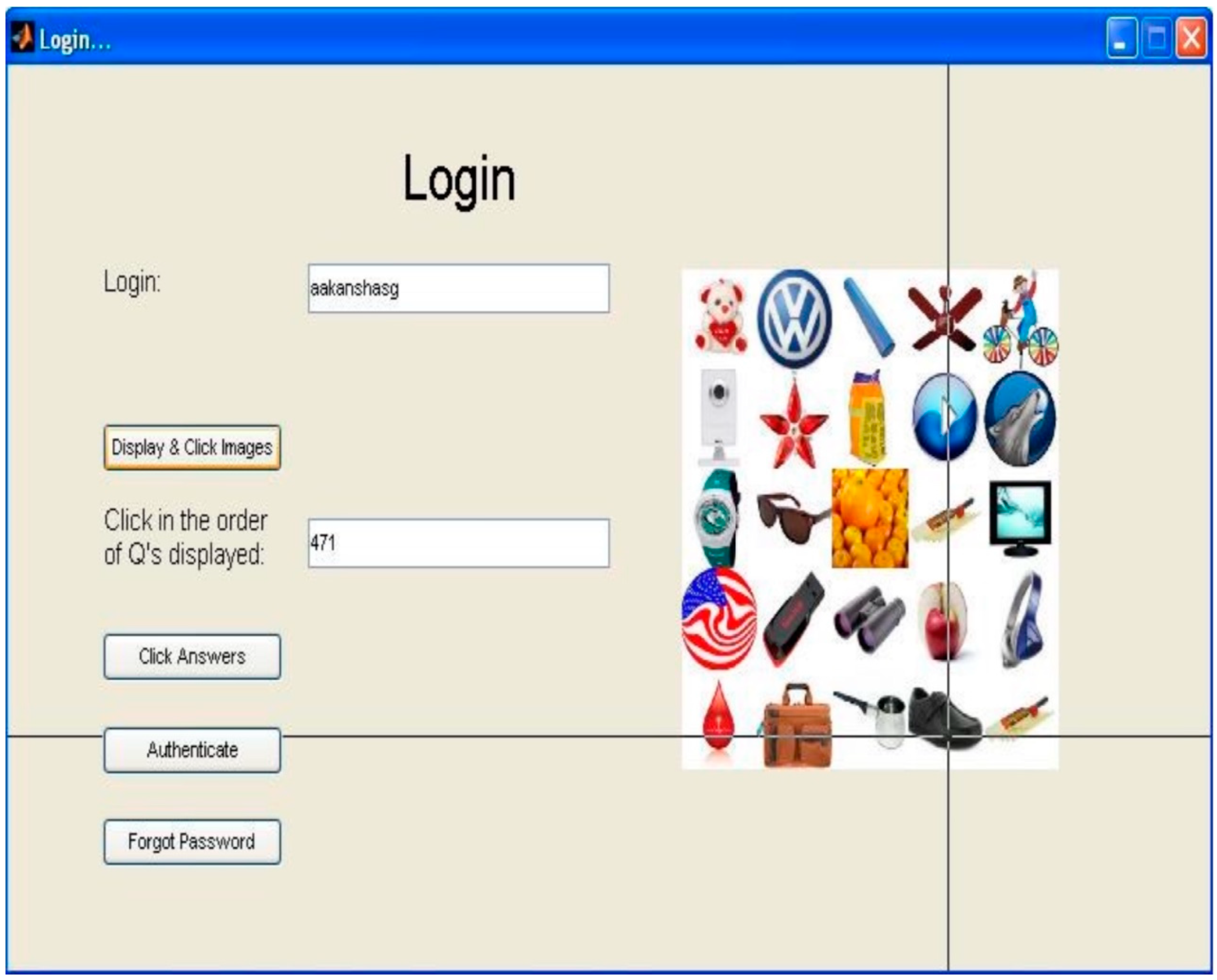

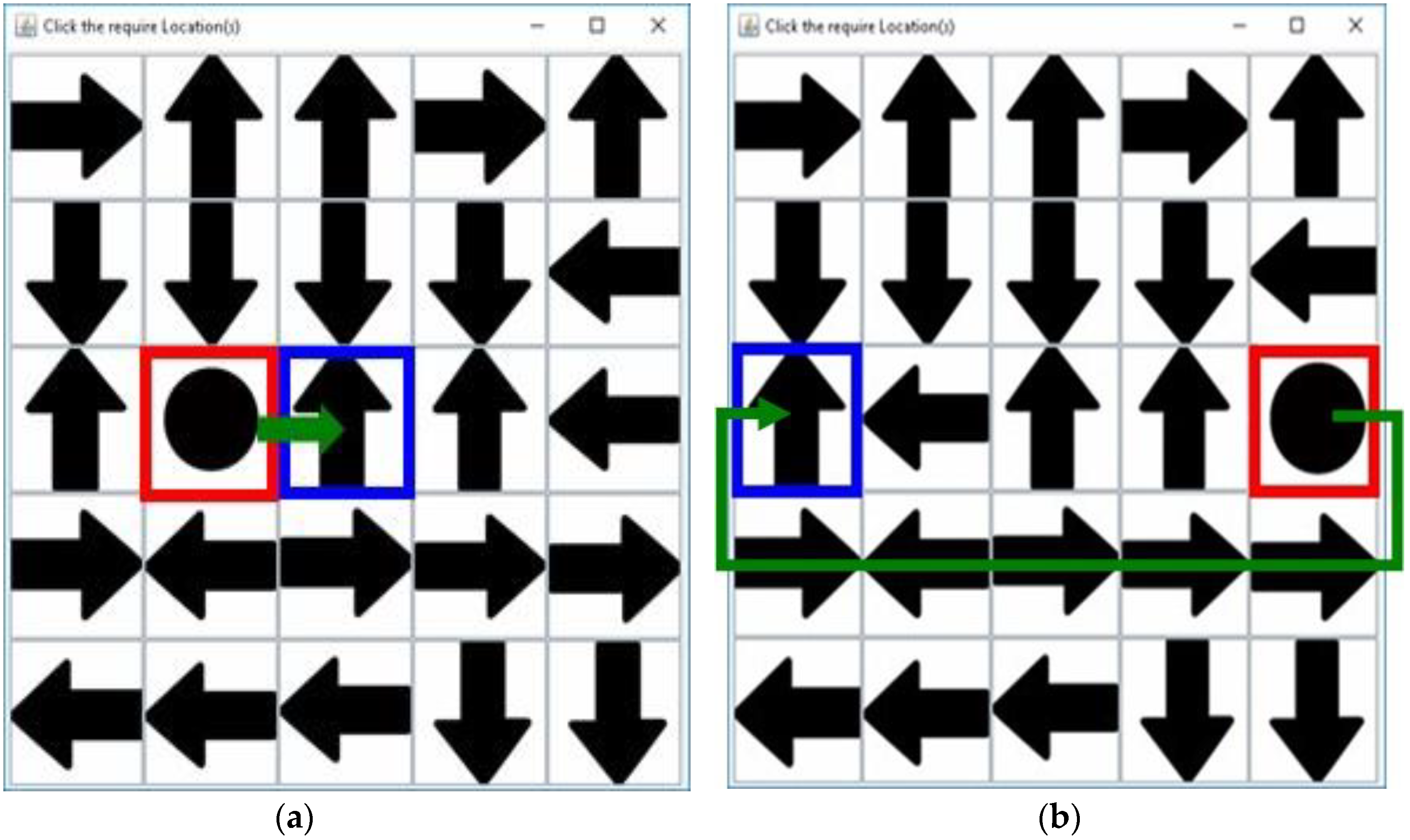

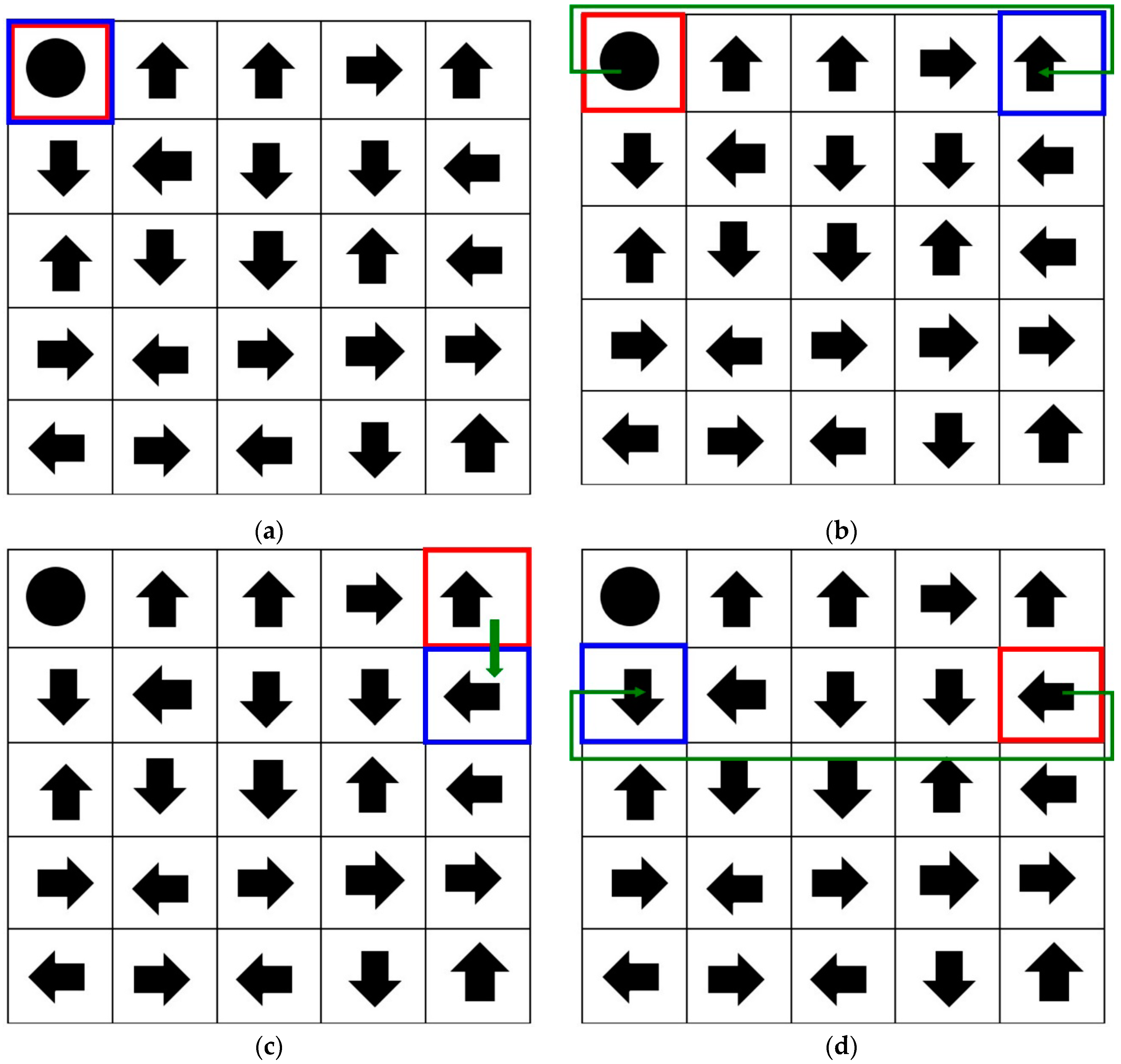

3.2. Authentication Procedure

3.3. Proposed Method

4. User Study

4.1. Hypothesis

4.2. Participants

4.3. Procedure

5. Results

5.1. Shoulder-Surfing Testing Result

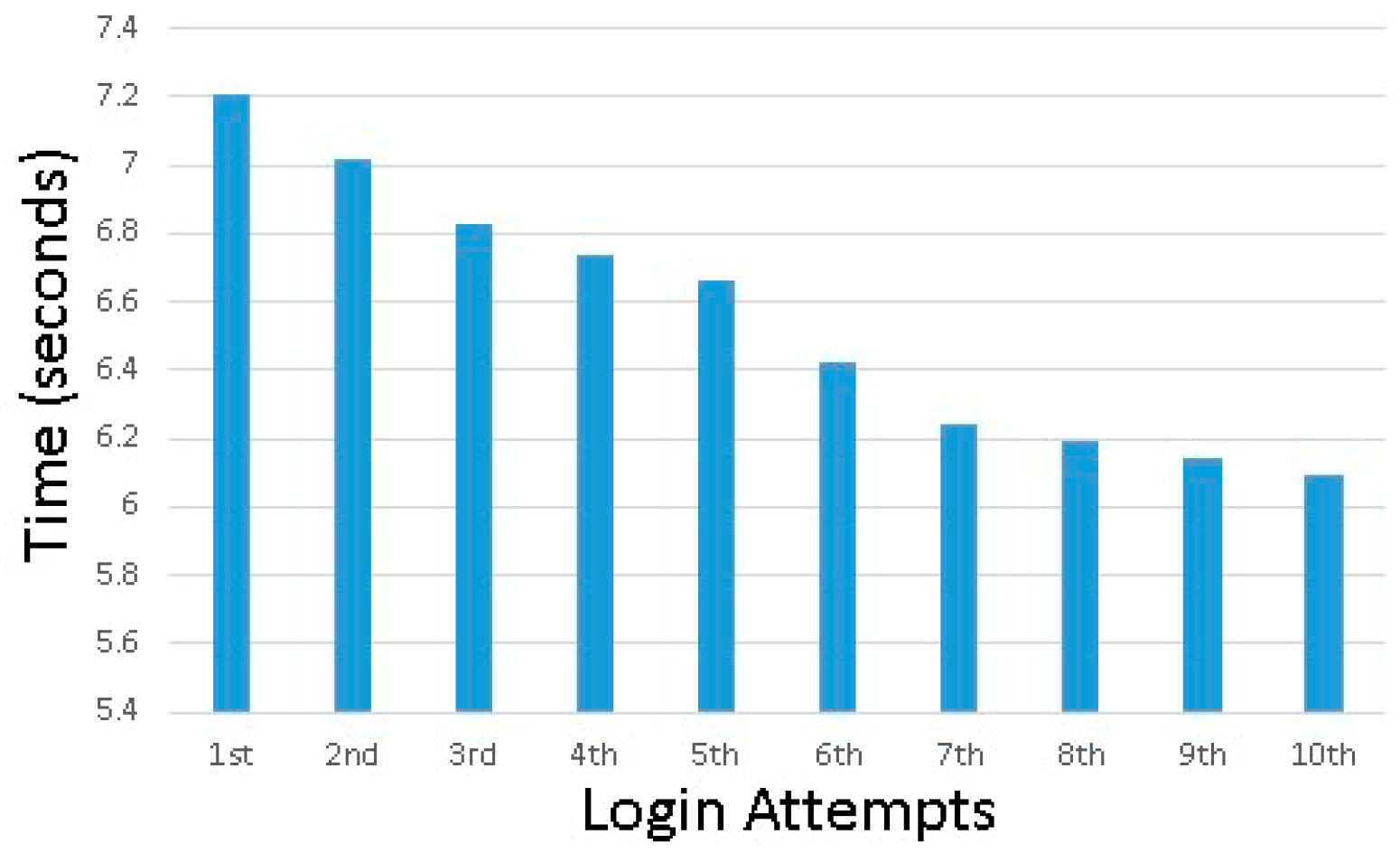

5.2. Usability Testing Result

5.3. Comparison with Other Selected Related Works

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Por, L.Y.; Ku, C.S.; Islam, A.; Ang, T.F. Graphical password: Prevent shoulder-surfing attack using digraph substitution rules. Front. Comput. Sci. 2017, 11, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamija, R.; Perrig, A. Deja Vu-A User Study: Using Images for Authentication. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium, Denver, CO, USA, 14–17 August 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, R.; Chiasson, S.; Van Oorschot, P. Graphical passwords: Learning from the first twelve years. J. ACM Comput. Surv. 2012, 44, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sahni, S.; Sabbu, P.; Varma, S.; Gangashetty, S.V. Passblot: A highly scalable graphical one time password system. Int. J. Netw. Secur. Appl. 2012, 4, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, R.A.; Kumaraguru, P.; Srinathan, K. WYSWYE: Shoulder surfing defense for recognition based graphical passwords. In Proceedings of the 24th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on—OzCHI ’12, Melbourne, Australia, 26–30 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ameen, M.N.; Wright, M.; Scielzo, S. Towards Making Random Passwords Memorable: Leveraging Users’ Cognitive Ability Through Multiple Cues. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing System, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, M.; Imran, A. A Comparative Study of Graphical and Alphanumeric Passwords for Mobile Device Authentication. In Proceedings of the 26th Modern AI and Cognitive Science Conference 2015, Greensboro, NC, USA, 25–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, W.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Cheng, B.R.; Chang, C.J. A sector-based graphical password scheme with resistance to login-recording attacks. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2015, 98, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.J.; Malwatkar, G.M. The graphical security system by using CaRP. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Energy Systems and Applications, Pune, India, 30 October–1 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Ahn, G.J.; Hu, H. Picture gesture authentication: Empirical analysis, automated attacks, and scheme evaluation. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2015, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.; Oakley, I.; Kim, H. PassBYOP: Bring your own picture for securing graphical passwords. IEEE T. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2016, 46, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assal, H.; Imran, A.; Chiasson, S. An exploration of graphical password authentication for children. Int. J. Child-Comp. Int. 2018, 18, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaiari, H.; Papadaki, M.; Dowland, P.S.; Furnell, S.M. A Review of Graphical Authentication Utilising a Keypad Input Method. In Proceedings of the Eighth Saudi Students Conference, London, UK, 31 January–1 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, M.; Dhane, D.M.; Mungle, T.; Chakraborty, R.; Deokamble, V.; Chakraborty, C. A Secure One-Time Password Authentication Scheme Using Image Texture Features. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Security in Computing and Communication, Jaipur, India, 21–24 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Por, L.Y.; Lim, X.T.; Su, M.T.; Kianoush, F. The design and implementation of background Pass-Go scheme towards security threats. WSEAS Trans. Inf. Sci. Appl. 2008, 5, 943–952. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.; Por, L.Y.; Othman, F.; Ku, C.S. A Review on Recognition-Based Graphical Password Techniques. In Computational Science and Technology, Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Alfred, R., Lim, Y., Ibrahim, A., Anthony, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.F.; Kam, Y.H.S.; Wee, M.C.; Chong, Y.N.; Por, L.Y. Preventing Shoulder-Surfing Attack with the Concept of Concealing the Password Objects’ Information. Sci. World. J. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Por, L.Y.; Ku, C.S.; Ang, T.F. Preventing Shoulder-Surfing Attacks using Digraph Substitution Rules and Pass-Image Output Feedback. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, M.A.S.; Waghmare, V.S. The shoulder surfing resistant graphical password authentication technique. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 79, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsini, C.; Raptis, G.E.; Fidas, C.; Avouris, N. Does image grid visualisation affect password strength and creation time in graphical authentication? In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, Castiglione della Pescaia, Grosseto, Italy, 29 May–1 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.M.; Chen, S.T.; Yeh, J.H.; Cheng, C.Y. A shoulder surfing resistant graphical authentication system. IEEE Trans. Depend. Secur. 2018, 15, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal Directions and Ordinal Directions: GEOLOUNGE. Available online: https://www.geolounge.com/cardinal-directions-ordinal-directions/ (accessed on 8 October 2017).

- Renaud, K.; De Angeli, A. Visual passwords: Cure-all or snake-oil? Commun. ACM 2009, 52, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, K.; Mayer, P.; Volkamer, M.; Maguie, J. Are Graphical Authentication Mechanisms as strong as Passwords. In Proceedings of the Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, Krakow, Poland, 8–11 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Por, L.Y. Frequency of occurrence analysis attack and its countermeasure. Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol. 2014, 10, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Por, L.Y.; Kiah, M.L.M. Shoulder surfing resistance using penup event and neighbouring connectivity manipulation. Malays. J. Comput. Sci. 2010, 23, 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Design Service (RDS) for the East Midlands/Yorkshire & the Humber 2007: Sampling and Sample Size Calculation. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ae57/ab527da5287ed215a9a3bf5f542ae19734ea.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Smith, Z.R.; Wells, C.S. Central Limit Theorem and Sample Size. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Northeastern Educational Research Association, Kerhonkson, New York, NY, USA, 18–20 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Gender | Count of Participants that Can Login via SSA 1 | Count of Participants that Can Prevent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO 2 | MO 3 | VR 4 | |||

| 1 | Female | 0% | 54.63% | 54.63% | 54.63% |

| Male | 0% | 45.37% | 45.37% | 45.37% | |

| 2 | Female | 0% | 23.33% | 23.33% | 23.33% |

| Male | 0% | 76.67% | 76.67% | 76.67% | |

| Total | 0% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| Item | Time (Seconds) |

|---|---|

| Minimum | 4.0 |

| Maximum | 20.0 |

| Mean | 6.55 |

| Median | 6.0 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.63 |

| Mode | 6.0 |

| Method | Min Login Time (Seconds) | Max Login Time (Seconds) | Mean Login Time (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WYSWTE [5] | No Specify | No Specify | No Specify |

| Ho et al. [17] | 16.1 | 184.2 | 53.5 |

| Por et al. [1] | 3.0 | 28.0 | 9.67 |

| 3DGUA [20] | No Specify | No Specify | No Specify |

| Sun et al. [21] | No Specify | No Specify | No Specify |

| Proposed Method | 4.0 | 20.0 | 6.55 |

| Method | DO 1 | MO 2 | VR 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WYSWTE [5] | Resist | Could not Resist | Could not Resist |

| Ho et al. [17] | Resist | Could not Resist | Resist |

| Por et al. [1] | Resist | Could not Resist | Could not Resist |

| 3DGUA [20] | Resist | Could not Resist | Could not Resist |

| Sun et al. [21] | Resist | Could not Resist | Could not Resist |

| Proposed Method | Resist | Resist | Resist |

| Method | Password Length (n) | Password Space in (r) Rounds |

|---|---|---|

| WYSWTE [5] | 4 | 28!/(28 − n)! |

| Ho et al. [17] | n | 25!/(25 − n)! |

| Por et al. [1] | 2 | (25!/(25 − n)!) × r |

| 3DGUA [20]—cannot register same image during registration phase | n | 150!/(150 − n)! × r |

| 3DGUA [20]—can register same image during registration phase | n | 150n × r |

| Sun et al. [21] | n | 77n × r |

| Proposed Method | n | 25r |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Por, L.Y.; Adebimpe, L.A.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Khaw, C.S.; Ku, C.S. LocPass: A Graphical Password Method to Prevent Shoulder-Surfing. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101252

Por LY, Adebimpe LA, Idris MYI, Khaw CS, Ku CS. LocPass: A Graphical Password Method to Prevent Shoulder-Surfing. Symmetry. 2019; 11(10):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101252

Chicago/Turabian StylePor, Lip Yee, Lateef Adekunle Adebimpe, Mohd Yamani Idna Idris, Chee Siong Khaw, and Chin Soon Ku. 2019. "LocPass: A Graphical Password Method to Prevent Shoulder-Surfing" Symmetry 11, no. 10: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101252

APA StylePor, L. Y., Adebimpe, L. A., Idris, M. Y. I., Khaw, C. S., & Ku, C. S. (2019). LocPass: A Graphical Password Method to Prevent Shoulder-Surfing. Symmetry, 11(10), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101252