Optimizing Estuarine Aquatic–Terrestrial Ecotone Landscapes Under Economic–Ecological Trade-Offs: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Land-Use Classification

2.2.2. Driving Factors

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Ecological Conservation Importance Assessment

2.3.2. CLUE-S Model

- 1.

- Weighting of driving factors

- 2.

- Spatiotemporal scale settings

- 3.

- Land-use conversion rules

2.3.3. Model Accuracy Validation

2.3.4. Scenario Settings

- 1.

- Markov chain model

- 2.

- Gray multi-objective optimization (GMOP) model

- Objective system construction

- Constraint settings

2.3.5. Benefit Comparison

3. Results

3.1. Model Validation Results

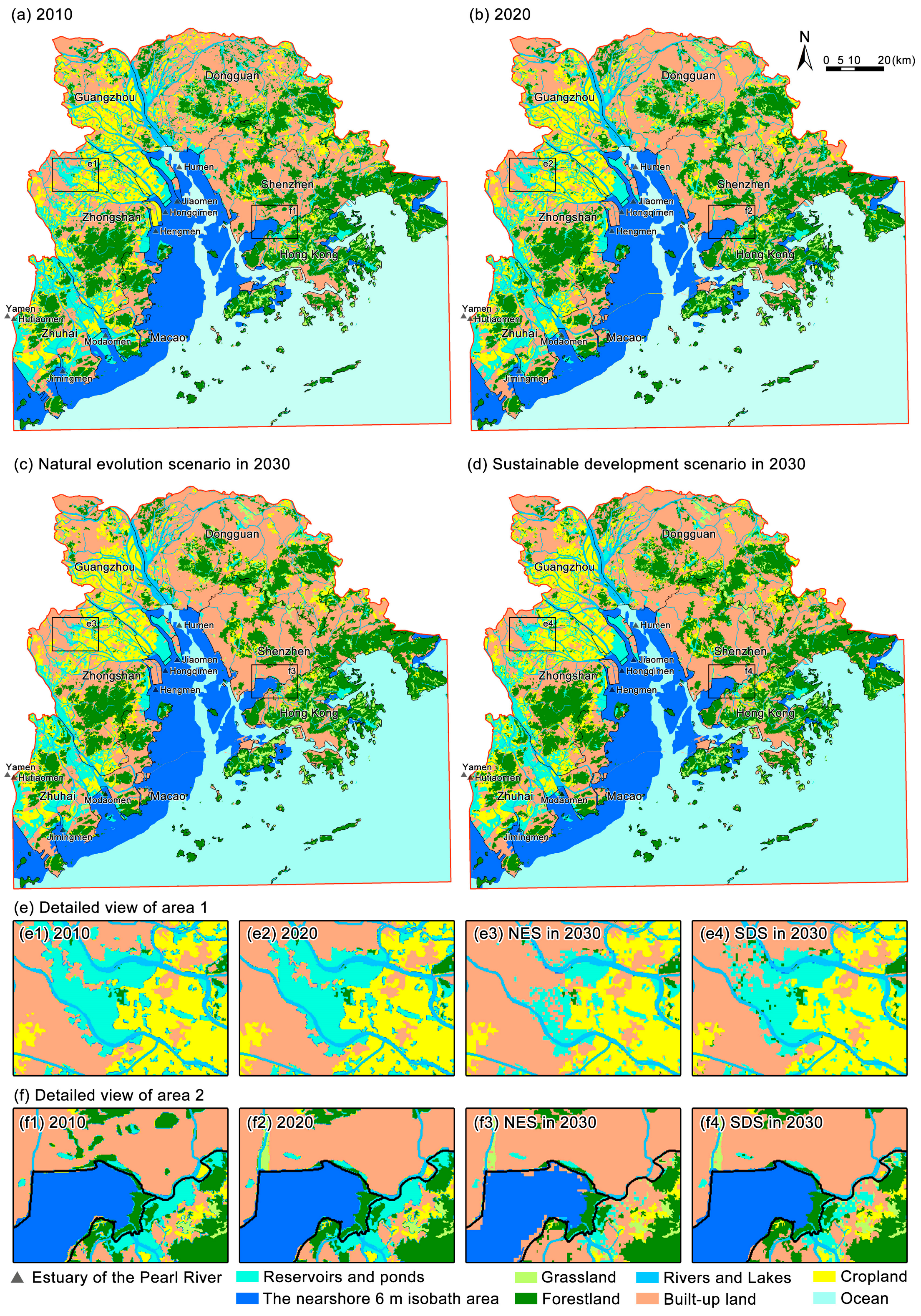

3.2. Landscape Pattern Evolution Characteristics

3.2.1. Dynamic Changes in Land-Use Types

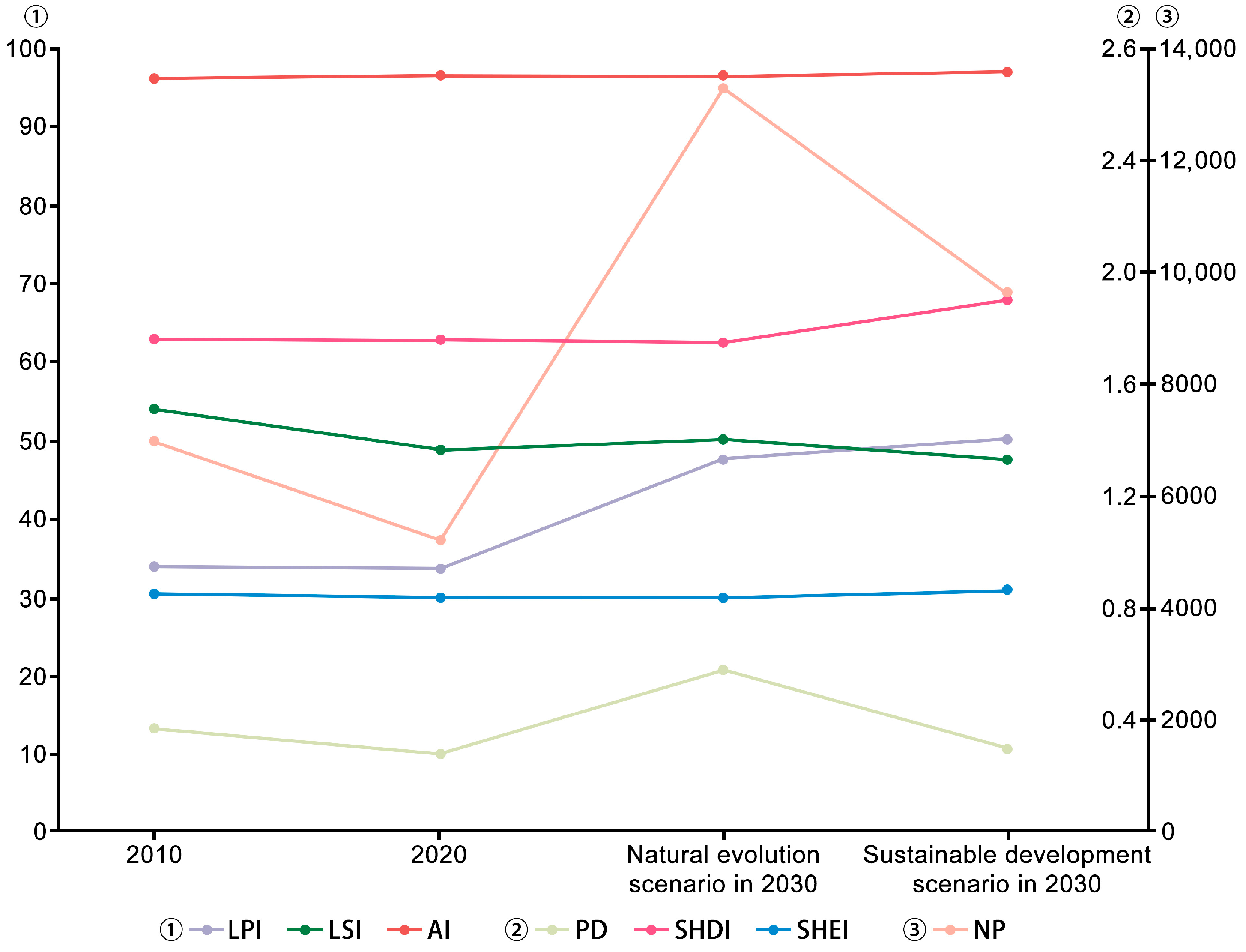

3.2.2. Dynamic Changes in Landscape Pattern

3.3. Comparison of Built-Up Land Encroachment on Priority Ecological Protection Areas

3.4. Economic and Ecological Benefit Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Model-Scale Selection and Simulation Accuracy Underpin This Study’s Reliability

4.2. The Evolution of Landscape Patterns in Estuarine Urban Agglomerations Clearly Reflects an Intense Interplay Between Human Activities and Natural Processes

4.3. Scenario-Based Comparison of Landscape Pattern and Ecological Conflicts

4.4. Policy Implications Based on Landscape Pattern Simulation and Optimization

4.5. Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- At the 50 × 50 m scale, the CLUE-S simulation for the 2020 land-use pattern shows high agreement with observations, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.904, indicating that the framework can be used to simulate pattern evolution in a complex aquatic–terrestrial ecotone. Landscape pattern change in the study area is mainly driven by rapid built-up land expansion. Encroachment of built-up patches on cropland, forestland, and water bodies is the main driver of landscape reorganization and ecological function degradation.

- (2)

- Although the natural evolution scenario increases economic benefits by 69.79%, it intensifies conflicts between built-up land and core ecological protection areas. In contrast, under planning constraints and ecological control, the sustainable development scenario avoids encroachment into high-importance ecological protection areas, improves overall ecological benefits, and maintains economic growth, with notable benefits for coastal ecological functions.

- (3)

- Embedding rigid constraints, including ecological redlines and shoreline controls, into land-use structure optimization and spatial allocation can curb unregulated built-up land expansion, particularly encroachment into ecologically sensitive areas such as estuaries and coastal zones, and guide more intensive development or orderly expansion at urban fringes. This approach can effectively alleviate conflicts between urban expansion and ecological protection and provides operational technical support and reference for land-use planning and classified management in rapidly urbanizing urban agglomerations.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brownstein, G.; Johns, C.; Fletcher, A.; Pritchard, D.; Erskine, P.D. Ecotones as Indicators: Boundary Properties in Wetland-Woodland Transition Zones. Community Ecol. 2015, 16, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawood, R.A.; Samways, M.J.; Pryke, J.S. Viable Conservation of Pondscapes Includes the Ecotones with Dryland. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 302, 110944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., 3rd; Zavaleta, E.S.; Eviner, V.T.; Naylor, R.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Reynolds, H.L.; Hooper, D.U.; Lavorel, S.; Sala, O.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Consequences of Changing Biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.B.; Wayne, R.K.; Girman, D.J.; Bruford, M.W. A Role for Ecotones in Generating Rainforest Biodiversity. Science 1997, 276, 1855–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T. Some General Principles of Landscape and Regional Ecology. Landsc. Ecol. 1995, 10, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-Resolution Mapping of Global Surface Water and Its Long-Term Changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichon, B.; Thebault, E.; Lacroix, G.; Gounand, I. Quality Matters: Stoichiometry of Resources Modulates Spatial Feedbacks in Aquatic-Terrestrial Meta-Ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1700–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel Barragan, J.; de Andres, M. Analysis and Trends of the World’s Coastal Cities and Agglomerations. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 114, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. The World Bank Annual Report 2010: Year in Review; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Quantifying the Spatial Impact of Landscape Fragmentation on Habitat Quality: A Multi-Temporal Dimensional Comparison between the Yangtze River Economic Belt and Yellow River Basin of China. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, G.; Zeng, J. Impact of Urbanization on Ecosystem Health in Chinese Urban Agglomerations. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilimigkas, G.; Rempis, N.; Derdemezi, E.-T. Marine Zoning and Landscape Management on Crete Island, Greece. J. Coast. Conserv. 2020, 24, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xie, B.; Liu, J. Scenario Simulation and Landscape Pattern Dynamic Changes of Land Use in the Poverty Belt around Beijing and Tianjin: A Case Study of Zhangjiakou City, Hebei Province. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 272–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.Z.; Renaud, J.; Biron, P.E.; Choler, P. Long-Term Modeling of the Forest-Grassland Ecotone in the French Alps: Implications for Land Management and Conservation. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Guo, Q.; Cheng, K.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z. Changes of Chinese Forest-Grassland Ecotone in Geographical Scope and Landscape Structure from 1990 to 2020. Ecography 2024, 2024, e07296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, T.; Cai, Y.; Fei, T.; Zhai, C.; Qi, W.; Dong, S.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Stable or Unstable? Landscape Diversity and Ecosystem Stability across Scales in the Forest-Grassland Ecotone in Northern China. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 3889–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Liu, M.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Mao, X.; Li, X.; Fan, J.; Chen, J.; Lv, Y.; et al. Assessing Land Cover and Ecological Quality Changes in the Forest-Steppe Ecotone of the Greater Khingan Mountains, Northeast China, from Landsat and MODIS Observations from 2000 to 2018. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Ding, H.; Fang, W.; Bi, R. Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Daylily Cultivation in the Farming-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China. Land 2024, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Peng, X.; Jia, G.; Yu, X.; Rao, H. Evaluation and Optimization of Landscape Spatial Patterns and Ecosystem Services in the Northern Agro-Pastoral Ecotone, China. Land 2024, 13, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodi, G.; Czegledi, I.; Eros, T. Drivers of the Taxonomic and Functional Structuring of Aquatic and Terrestrial Floodplain Bird Communities. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, T. Interplay of Natural and Anthropogenic Factors on Plant Diversity at the Aquatic-Terrestrial Interface of Yuhangtang River. Wetlands 2024, 44, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, W.; Verburg, P.H.; Leip, A. Modelling of Land Cover and Agricultural Change in Europe: Combining the CLUE and CAPRI-Spat Approaches. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 142, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, X. Simulation of Land-Use Scenarios for Beijing Using CLUE-S and Markov Composite Models. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Du, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Mao, F.; Zhu, D.; He, S.; Liu, H. Spatiotemporal LUCC Simulation under Different RCP Scenarios Based on the BPNN_CA_Markov Model: A Case Study of Bamboo Forest in Anji County. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf 2020, 9, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guan, Q.; Clarke, K.C.; Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Yao, Y. Understanding the Drivers of Sustainable Land Expansion Using a Patch-Generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) Model: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 85, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziridis, D.A.; Mastrogianni, A.; Pleniou, M.; Tsiftsis, S.; Xystrakis, F.; Tsiripidis, I. Simulating Future Land Use and Cover of a Mediterranean Mountainous Area: The Effect of Socioeconomic Demands and Climatic Changes. Land 2023, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiakou, S.; Vrahnakis, M.; Chouvardas, D.; Mamanis, G.; Kleftoyanni, V. Land Use Changes for Investments in Silvoarable Agriculture Projected by the CLUE-S Spatio-Temporal Model. Land 2022, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gong, Q.; Liu, B.; Yu, S.; Yan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J. Integrating Linear Programming and CLUE-S Modeling for Scenario-Based Land Use Optimization Under Eco-Economic Trade-Offs in Rapidly Urbanizing Regions. Land 2025, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Lu, X.; Han, J. Trade-Offs and Driving Forces of Land Use Functions in Ecologically Fragile Areas of Northern Hebei Province: Spatiotemporal Analysis. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulsoontornrat, J.; Ongsomwang, S. Suitable Land-Use and Land-Cover Allocation Scenarios to Minimize Sediment and Nutrient Loads into Kwan Phayao, Upper Ing Watershed, Thailand. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fang, C.; Zhao, R.; Zhu, C.; Guan, J. Spatial-Temporal Evolution and Driving Force Analysis of Eco-Quality in Urban Agglomerations in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Tang, L.; Wei, X.; Li, Y. Spatial Interaction between Urbanization and Ecosystem Services in Chinese Urban Agglomerations. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y. Construction of an Ecological Security Pattern Based on Ecosystem Sensitivity and the Importance of Ecological Services: A Case Study of the Guanzhong Plain Urban Agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chatterjee, N.D.; Dinda, S. Urban Ecological Security Assessment and Forecasting Using Integrated DEMATEL-ANP and CA-Markov Models: A Case Study on Kolkata Metropolitan Area, India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Xu, S.; He, X.; Yao, J.; Huang, Y. Analysis of Trade-off and Synergy of Ecosystem Services and Driving Forces in Urban Agglomerations in Northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Li, Y.; Quan, X.; Huang, G.; Xu, J. Exploring the Trade-Offs and Synergies among Ecosystem Services to Support Ecological Management in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liao, L.; Tan, X.; Yu, R.; Zhang, K. City Health Assessment: Urbanization and Eco-Environment Dynamics Using Coupling Coordination Analysis and FLUS Model-A Case Study of the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Land 2025, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Urban Wilderness: Supply, Demand, and Access. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Long, X.; Song, Y.; Lu, F.; Song, J.; Zhang, B.; Han, G. Spatial-Temporal Variations and Driving Factors of Coastal Aquaculture Ponds in China from 1985 to 2023. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 36, 1519–1530. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, H.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, W.; Qiu, Q.; Tang, L. Impact of Land Use Change on the Water Conservation Service of Ecosystems in Theurban Agglomeration of the Golden Triangle of Southern Fujian, China, in 2030. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 484–498. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abro, T.W.; Debie, E. Soil Erosion Assessment for Prioritizing Soil and Water Conservation Interventions in Gotu Watershed, Northeastern Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. Assessment Guidelines for Resource and Environmental Carrying Capacity and Territorial Development Suitability; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, R.; Li, K. Ecological Red Line Zoning of the Tibet Autonomous Region Based on Ecosystem Services and Ecological Sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 67, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Ni, H.; Chen, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J. Evaluation of Ecological Conservation Importance of Fujian Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 1130–1141. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W. The Simulation of the Ecological Land Change Based on CLUE-S and Markov Model. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 39, 52–57+63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Hu, Y. Assessing Temporal-Spatial Land Use Simulation Effects with CLUE-S and Markov-CA Models in Beijing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 32231–32245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.-Y.; Huang, G.; Zi, P.; Li, T.; Liang, Q. Implementation of Ecological Risk Scenario Simulation and Driving Mechanisms in Typical Rocky Desertification Regions in China: A Coupling Multi-Model Ecological Assessment Framework. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 174, 113464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, R.; Men, C.; Wang, Q.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Quantifying and Simulating Landscape Composition and Pattern Impacts on Land Surface Temperature: A Decadal Study of the Rapidly Urbanizing City of Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, M.; Xing, A.; Sun, Z.; Huang, Y. Modelling the Spatial Expansion of Green Manure Considering Land Productivity and Implementing Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Mai, X.; Shen, G. Delineation of Urban Growth Boundaries with SD and CLUE-s Models under Multi-Scenarios in Chengdu Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J.M. Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Sikder, M.B. Shoreline Dynamics in the Reserved Region of Meghna Estuary and Its Impact on Lulc and Socio-Economic Conditions: A Case Study from Nijhum Dwip, Bangladesh. J. Coast. Conserv. 2024, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, N.; Wu, M.; Wu, P.; He, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Fang, S. The Scale Identification Associated with Priority Zone Management of the Yangtze River Estuary. Ambio 2022, 51, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Cheng, Q.; Tsou, J.Y.; Huang, B.; Ji, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Investigating Spatiotemporal Coastline Changes and Impacts on Coastal Zone Management: A Case Study in Pearl River Estuary and Hong Kong’s Coast. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 257, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, F.; Su, F.; Lyne, V.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Response of Habitat Quality to Land Use Changes in The Johor River Estuary. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2390439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Q.; Qiu, H.; Du, J.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Z.; He, Y. Study on Ecosystem Service Trade-Offs and Synergies in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Based on Ecosystem Service Bundles. Land 2024, 13, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J. A New Approach to Evaluate the Sustainability of Ecological and Economic Systems in Megacity Clusters: A Case Study of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.A.; Nakagoshi, N. Changes in Landscape Spatial Pattern in the Highly Developing State of Selangor, Peninsular Malaysia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 77, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, M.; Goldstein, N.; Clarke, K. The Spatiotemporal Form of Urban Growth: Measurement, Analysis and Modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lin, W. Exploring Cultivated Land Trade-off/Synergy of Production and Ecological Supply-Demand Mismatch for Coordinated Development: Evidence from Mega Urban Agglomeration. Environ. Dev. Sustain 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Del Castillo, E.; García-Martin, A.; Longares Aladrén, L.A.; De Luis, M. Evaluation of Forest Cover Change Using Remote Sensing Techniques and Landscape Metrics in Moncayo Natural Park (Spain). Appl. Geogr. 2015, 62, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yi, K.; et al. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Service Values and Topography-Driven Effects Based on Land Use Change: A Case Study of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ma, C. Chain-Spectrum Analysis of Land Use/Cover Change Based on Vector Tracing Method in Northern Oman. Land 2025, 14, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Na, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Qu, Z.; Lv, S.; Jiang, R.; Sun, N.; Hao, D. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Vegetation Coverage and Its Response to Land-Use Change in the Agro-Pastoral Ecotone of Inner Mongolia, China. Land 2025, 14, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Indicator | Calculation Method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem service function importance | Water conservation | (1) | [40] | |

| WC denotes water conservation; Fpre is the multi-year mean precipitation; R is surface runoff; ET is evapotranspiration. | ||||

| Soil conservation | (2) | [41] | ||

| SC denotes soil conservation; R is rainfall erosivity; S is slope; K is soil erodibility; C is vegetation cover; L is slope length. | ||||

| Coastal protection | We followed China’s Guidelines for Resource Environment Carrying Capacity and Territorial Spatial Development Suitability Evaluation. Extremely important coastal protection zones are coasts with high authenticity and integrity that require priority protection. High-function zones include mangroves, shelterbelts, tidal flats, and other natural shoreline types. Medium-function zones include dike–pond coasts and bedrock coasts. Low-function zones include artificial hard coasts and sandy coasts. | [42] | ||

| Biodiversity maintenance | (3) | [43] | ||

| Q denotes biodiversity maintenance; NPPmean is the multi-year mean net primary productivity; Fpre is the multi-year mean precipitation; Ftem is the multi-year mean air temperature; Falt is altitude. | ||||

| Ecological sensitivity | Soil erosion | (4) | [42] | |

| SE denotes soil erosion sensitivity; R is rainfall erosivity; K is soil erodibility; LS is topographic relief; C is vegetation cover. | ||||

| Coastal erosion | Coastal erosion sensitivity is classified by coastal geomorphology: low for artificial hard revetments, bedrock coasts, and dike–pond coasts; medium for shelterbelts, mariculture areas, mangroves, and other natural shoreline types; and high for tidal flats, major estuarine zones, and sandy coasts [44]. | [42] | ||

| Type | Basis | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Total area | The sum of all the areas of all the decision variables equals the total study area. | |

| Forestland | The natural background is fragile, and degradation of forestland readily triggers soil erosion and desertification. Following the Outline of Guangdong Territorial Greening Plan, some low-quality and low-efficiency forestland is allowed to undergo structural optimization and functional restoration within ecological land, whereas conversion of forestland to built-up land or grassland is strictly prohibited. Accordingly, this study constrained forestland area change to prevent forestland loss and to ensure a net increase. | X2 > 287,137.75 |

| Rivers and lakes | The river chief system and the lake chief system have been fully implemented. Rivers and lakes are effectively protected, and their area should continue to increase. | X3 > 44,908.25 |

| Reservoirs and ponds | Municipal policy documents indicate that the area of reservoirs and ponds supporting aquaculture and planting will continue to decrease. Dike–pond agriculture is an important agricultural heritage and should be protected. Therefore, the rate of decrease in reservoirs and ponds should be moderated. | 84,121.47 < X4 < 94,950.25 |

| The nearshore 6 m isobath area | China’s 14th Five-Year Plans for Ecological Civilization and for the Marine Economic Belt call for major ecological restoration of key estuaries and nearshore wetlands and biodiversity. Therefore, the rate of decrease in the nearshore 6 m isobath area should be moderated and may achieve net growth. | X5 > 209,418.75 |

| Cropland | Permanent basic farmland zones are delineated, and farmland protection is strict. Therefore, the rate of decrease in cropland will decline. | 158,676.64 < X6 < 167,843 |

| Built-up land | The Pearl River Estuary is a key marine-industry cluster and a core Belt and Road economic zone. Therefore, the growth rate of built-up land should be controlled, and encroachment on ecological land-use types should be restricted. | 392,944.25 < X7 < 508,446.24 |

| Type | 2020 | Natural Evolution Scenario | Sustainable Development Scenario | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Benefits | Ecological Benefits | Economic Benefits | Ecological Benefits | Economic Benefits | Ecological Benefits | |

| Grassland | 0.16 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.49 |

| Forestland | 0.01 | 6.32 | 0.01 | 6.19 | 0.01 | 6.59 |

| Rivers and lakes | 0.01 | 6.60 | 0.01 | 6.71 | 0.01 | 6.68 |

| Reservoirs and ponds | 0.11 | 13.95 | 0.15 | 12.36 | 0.16 | 13.81 |

| The nearshore 6 m isobath area | 0.06 | 12.75 | 0.08 | 12.56 | 0.09 | 12.84 |

| Cropland | 1.64 | 1.29 | 2.39 | 1.16 | 2.40 | 1.16 |

| Built-up land | 798.55 | 0.00 | 1356.59 | 0.00 | 1279.15 | 0.00 |

| Ocean | 0.52 | 92.94 | 0.81 | 93.08 | 0.81 | 92.96 |

| Total | 801.06 | 134.40 | 1360.08 | 132.70 | 1282.66 | 134.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, K.; Lin, W. Optimizing Estuarine Aquatic–Terrestrial Ecotone Landscapes Under Economic–Ecological Trade-Offs: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta. Land 2026, 15, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010042

Li H, Xu Z, Wang S, Xu Q, Chen Z, Liu K, Lin W. Optimizing Estuarine Aquatic–Terrestrial Ecotone Landscapes Under Economic–Ecological Trade-Offs: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta. Land. 2026; 15(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hui, Zhenzhou Xu, Shuntao Wang, Qing Xu, Ziyi Chen, Kaiyan Liu, and Wei Lin. 2026. "Optimizing Estuarine Aquatic–Terrestrial Ecotone Landscapes Under Economic–Ecological Trade-Offs: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta" Land 15, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010042

APA StyleLi, H., Xu, Z., Wang, S., Xu, Q., Chen, Z., Liu, K., & Lin, W. (2026). Optimizing Estuarine Aquatic–Terrestrial Ecotone Landscapes Under Economic–Ecological Trade-Offs: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta. Land, 15(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010042