Exploring the Pattern of Residential Space Differentiation in a Megacity’s Fringe Areas and Its Influence Mechanism: Insights from Beijing, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Framework and Methods

2.1. Analytical Framework

2.2. Study Area and Data Sources

2.2.1. Study Area

2.2.2. Data Sources

2.2.3. Scale Selection

2.3. Research Method

2.3.1. Calculation of Residential Space Differentiation Index

2.3.2. Impact Factorization Based on the Optimal Parameter Geographic Detector

2.3.3. Influence Mechanism Analysis Based on Multi-Scale Geographic Weighted Regression Model

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Residential Space Differentiation in Urban Fringe Areas of Beijing

3.1.1. Analysis of Different Spatial Scales

3.1.2. Analysis of Different Housing Types

3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Residential Space Differentiation in Urban Fringe Areas of Beijing

3.2.1. Variable Selection and Description

3.2.2. Factor Detection Analysis

3.2.3. Interactive Detection

3.3. Analysis of Influencing Mechanism of Residential Space Differentiation in Urban Fringe Areas of Beijing

3.3.1. Impact Factor Screening

3.3.2. Model Contrast Optimization

3.3.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors

4. Discussions

4.1. Formative Mechanism of Residential Space Differentiation Phenomenon in Urban Fringe Area of Beijing

4.2. Influence Mechanism of Residential Space Differentiation in Urban Fringe Area of Beijing

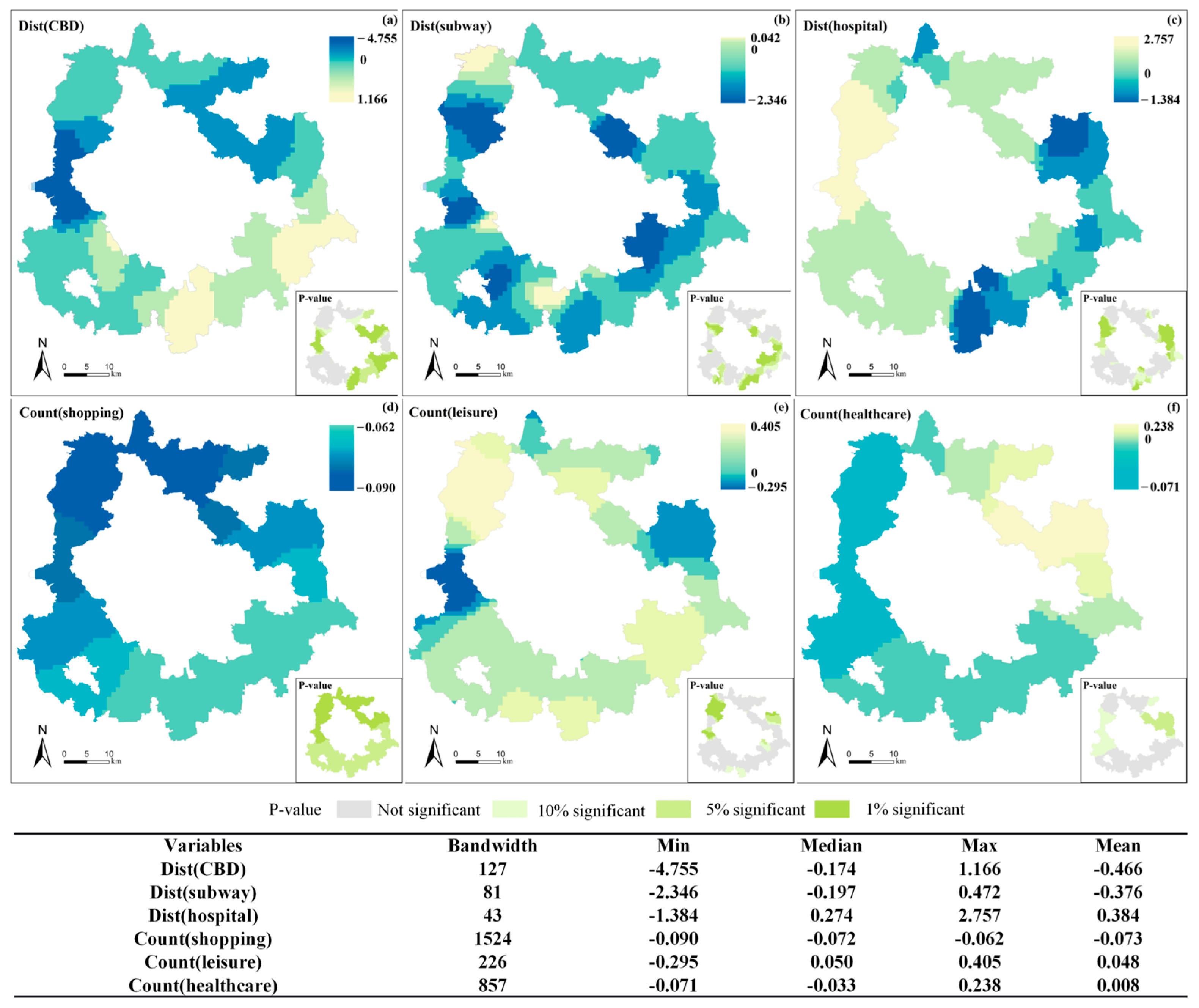

- Mechanism of the central position factor. The differentiation of residential space in Beijing’s urban fringe area is firstly reflected in the difference in dependence on the urban center area, which is related to the multi-center spatial structure strategy in the process of urbanization. This strategy has promoted the rise in many centers, such as the CBD in the northeast of Beijing, Tongzhou District sub-center, and Yizhuang New City in the southeast, each of which has formed a strong siphon and agglomeration effect. This macro layout plan not only attracts a large number of floating populations to choose their residential location based on employment distribution, but also strengthens the typical land rent gradient under the action of the rent competition mechanism, further solidifying the situation that high-income groups live near the center and low-income groups live in the periphery [43]. Specifically, the northern and western edge areas are affected by the radiation of shopping malls and enterprises in the CBD, attracting a large number of migrant workers engaged in basic service industries such as take-out, express delivery, and cleaning, as well as some highly educated and skilled professional and technical personnel. These floating populations usually choose to obtain limited residential space in neighboring villages with lower total rent or rent houses in farther areas in order to reduce the rent per unit area, thus maintaining and strengthening the gradient dependence on the CBD in space. In contrast, the southeastern edge area, driven by the city sub-center and its surrounding logistics bases, automobile manufacturing parks, and other functional nodes, provides a large number of workers’ jobs for the floating population and attracts them to live in the surrounding areas through low-cost living resources such as supporting dormitories, thus significantly weakening their single dependence on the CBD.

- Mechanism of the transportation position factor. The residential space differentiation in Beijing’s urban fringe area is significantly affected by the local negative correlation of traffic potential factors, which are the premium effects of track accessibility on the surrounding area [44,45]. As an efficient channel connecting marginal areas and core employment areas, subway stations can improve the accessibility of land plots, affect residents’ travel decisions and land development and utilization, and have a significant premium effect on surrounding areas. Compared with urban areas, due to the weakness of the secondary transportation network, subway stations in marginal areas play a more irreplaceable role in the commuting guarantee of floating populations, which makes floating populations regard “distance from subway stations” as a key consideration in renting a house. The planning and construction of subway stations and the demand of floating populations will lead to a situation where the surrounding stations are highly developed and the peripheral areas are lagging behind, further amplifying the degree of differentiation. In addition, the weakening effect of this effect in the southwestern suburbs and northwestern suburbs of Beijing comes from the fact that the nearby employment of residents in these areas reduces the dependence on long-distance rail transit frequency, and the marginal utility of traffic potential decreases, so its influence is weakened.

- Mechanism of the recreational amenities factor. The differentiation of residential space in Beijing’s urban fringe area is positively affected by leisure supporting factors, which reflects the differentiated preferences and consumption willingness of different groups for leisure supporting facilities. With the improvement of income level, the demand of floating populations will change from “survival” to “development” and “enjoyment” with the improvement of income level. As a scarce and exclusive social resource, high-quality leisure facilities (golf courses, hot springs, Universal Studios, etc.) can not only significantly improve the quality of the living environment, but also bear the social and identity consumption demand of the middle-class and above income groups. In this process, these kinds of leisure supporting facilities gradually transform into spatial capital with screening functions. By pushing up the surrounding housing rent and land value, they guide capital and middle- and high-income groups to gather in specific areas, thus forming a significant rent premium and strengthening the social stratification structure spatially. In contrast, areas that lack such facilities and rely on basic functions are more likely to absorb low-consumption groups oriented to cost minimization, thus forming significant spatial differentiation between different areas [46].

- Mechanism of the medical support factor. The residential space differentiation in urban fringe areas of Beijing is only affected by the negative effects of three medical resources in a few areas, and the influence of secondary medical resources is weak, which is related to the imbalance of the spatial allocation of medical resources and the mismatch between supply and demand. Tertiary medical resources are mainly concentrated in the core areas due to administrative planning constraints, while high-quality secondary medical resources also lack effective supply in the market, resulting in shortcomings in both the quality and quantity of medical resources in marginal areas. However, according to the actual survey, the floating population in the marginal area is mainly young and middle-aged, with relatively stable physical health and low demand for major medical services. Most of the daily basic medical needs can be met through community clinics. Therefore, under limited housing affordability, even if the medical supporting resources are unevenly distributed, it is difficult to form an effective spatial differentiation driving effect in the marginal rental market [47,48].

4.3. Policy Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knox, P.; Pinch, S. Urban Social Geography: An Introduction, 6th ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-317-90326-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.; Johnston, R.; Forrest, J.; Charlton, C.; Manley, D. Ethnic and Class Residential Segregation: Exploring Their Intersection—A Multilevel Analysis of Ancestry and Occupational Class in Sydney. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1163–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Deng, L.; Kwan, M.-P.; Yan, R. Social and Spatial Differentiation of High and Low Income Groups’ out-of-Home Activities in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2015, 45, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhou, C.; Jin, W. Integration of Migrant Workers: Differentiation among Three Rural Migrant Enclaves in Shenzhen. Cities 2020, 96, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, G. The Structure of Social Space in Beijing in 1998: A Socialist City in Transition. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Young, C. Social Differentiation and Spatial Mixture in a Transitional City—Kunming in Southwest China. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xiao, Y. Emerging Divided Cities in China: Socioeconomic Segregation in Shanghai, 2000–2010. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 1338–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, S.; Mo, H. Housing Differentiation in Transitional Urban China. Cities 2020, 96, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, D.; Lin, X.; Lu, Y. Residential Differentiation Characteristics Based on “Socio-Spatial” Coupling: A Case Study of Zhengzhou. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 166, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Xing, M.; Wu, C. A Review of International Residential Spatial Divergence Research from the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Relationship. Urban Probl. 2023, 5, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Huang, Q.; Gu, Y.; He, G. Unraveling the Multi-Scalar Residential Segregation and Socio-Spatial Differentiation in China: A Comparative Study Based on Nanjing and Hangzhou. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 1757–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Nielsen, C.P.; Wu, J.; Chen, X. Examining Socio-Spatial Differentiation under Housing Reform and Its Implications for Mobility in Urban China. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Shi, D.; Hui, E.C. Urban Residential Space Differentiation and the Influence of Accessibility in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 124, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; He, S.Y.; Luo, S. The Influence of Job Accessibility on Local Residential Segregation of Ethnic Minorities: A Study of Hong Kong. Popul. Space Place 2020, 26, e2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Yeh, A.G.; Yue, Y. Workplace Segregation of Rural Migrants in Urban China: A Case Study of Shenzhen Using Cellphone Big Data. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokem, J.; Vaughan, L. Geographies of Ethnic Segregation in Stockholm: The Role of Mobility and Co-Presence in Shaping the ‘Diverse’ City. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2426–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurichev, N.; Kuricheva, E. Interregional Migration, the Housing Market, and a Spatial Shift in the Metro Area: Interrelationships in the Case Study of Moscow. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2020, 12, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, W. Location and Land Use: Towards a General Theory of Land Rent; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.A.V. Changing Residential Preferences across Income, Education, and Age: Findings from the Multi-City Study of Urban Inequality. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009, 44, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.; Gyourko, J. The Economic Implications of Housing Supply. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Migrant Settlement and Spatial Distribution in Metropolitan Shanghai. Prof. Geogr. 2008, 60, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Housing Migrant Workers in Rapidly Urbanizing Regions: A Study of the Chinese Model in Shenzhen. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Stuck in the Suburbs? Socio-Spatial Exclusion of Migrants in Shanghai. Cities 2017, 60, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, R. Housing Migrants in Chinese Cities: Current Status and Policy Design. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jin, C.; Li, T. A Paradox of Economic Benefit and Social Equity of Green Space in Megacity: Evidence from Tianjin in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 109, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Mao, N.; Chen, P.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y. Coupling Mechanism and Spatial-Temporal Pattern of Residential Differentiation from the Perspective of Housing prices—A Case Study of Nanjing. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wu, Q. Gentrification and Residential Differentiation in Nanjing, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Zhang, W.; Chunyu, M.D. Emergent Ghettos: Black Neighborhoods in New York and Chicago, 1880–1940. Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 120, 1055–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku-Boansi, M.; Tetteh, N.; Adarkwa, K.K. Preferences for Rental Housing in Urban Ghana: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Long, Y.; Wang, X.; Hou, J. Urban Redevelopment at the Block Level: Methodology and Its Application to All Chinese Cities. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1725–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, O.D.; Duncan, B. A methodological analysis of segregation indexes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1955, 20, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Yang, W.; Kang, W. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR). Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Li, Z. The causal effect of residential spatial segregation on the provision of public services: Evidences from Shanghai. Prog. Geogr. 2023, 42, 1795–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, N.A.; Massey, D.S. Residential Segregation of Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians by Socioeconomic Status and Generation. Soc. Sci. Q. 1988, 69, 797–817. [Google Scholar]

- Arbaci, S. (Re)Viewing Ethnic Residential Segregation in Southern European Cities: Housing and Urban Regimes as Mechanisms of Marginalisation. Hous. Stud. 2008, 23, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; He, J.; Song, W. Relationship between Residential Patterns and Socioeconomic Statuses Based on Multi-Source Spatial Data: A Case Study of Nanjing, China. Land 2024, 13, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.-M. Agglomeration and Simplified Housing Boom. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 936–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.A. Residential Income Segregation and Commuting in a Latin American City. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 117, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lin, T.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, M.; Yu, Z. Residential Spatial Differentiation Based on Urban Housing Types—An Empirical Study of Xiamen Island, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wan, J. Land Use and Travel Burden of Residents in Urban Fringe and Rural Areas: An Evaluation of Urban-Rural Integration Initiatives in Beijing. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Jeong, B.; Go, S. Exploring Urban Amenity Accessibility within Residential Segregation: Evidence from Seoul’s Apartment Housing. Land 2024, 13, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Song, Y.; Xu, D.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Wu, P.; Hou, W.; Xiao, Z. Interpreting Differences in Access and Accessibility to Urban Greenspace through Geospatial Analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 129, 103823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-López, M.-À.; Moreno-Monroy, A.I. Income Segregation in Monocentric and Polycentric Cities: Does Urban Form Really Matter? Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 71, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, P.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J. Walking Accessibility to the Bus Stop: Does It Affect Residential Rents? The Case of Jinan, China. Land 2022, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerch, R.; Barwick, P.J.; Li, S.; Wu, J. The Impact of Road Rationing on Housing Demand and Sorting. J. Urban Econ. 2024, 140, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M. How Do Urban Amenities Shape Knowledge-Intensive Industry Locations within Cities? A Multi-Scalar Study of Wuhan, China. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 180, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, S.; Qi, W. Spatial Differentiation and Influencing Mechanism of Medical Care Accessibility in Beijing: A Migrant Equality Perspective. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Bai, J.; Feng, R. Evaluating the Spatial Accessibility of Medical Resources Taking into Account the Residents’ Choice Behavior of Outpatient and Inpatient Medical Treatment. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 83, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Hachem-Vermette, C. Impact of Commercial Land Mixture on Energy and Environmental Performance of Mixed Use Neighbourhoods. Build. Environ. 2019, 154, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wei, L.; López-Carr, D.; Dang, X.; Yuan, B.; Yuan, Z. Identification of Irregular Extension Features and Fragmented Spatial Governance within Urban Fringe Areas. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 162, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Type | Explanatory Variant | Encode/Units | Variable Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location conditions | Central position | Dist(CBD)/km | Distance from space point to Beijing International Trade Center |

| Transportation position | Dist(subway)/km | Distance from the space point to the nearest subway station | |

| Count(bus)/pcs | Number of bus stops within 800 m of the space point | ||

| Supporting amenities | Commercial amenities | Count(shopping)/pcs | Number of supermarkets and convenience stores within 800 m of the space point |

| Recreational amenities | Count(leisure)/pcs | Number of parks, green spaces, squares, cultural centers, etc., within 800 m of the space point | |

| Educational amenities | Count(school)/pcs | Number of schools (kindergartens, elementary school, secondary schools) within 800 m of the space point | |

| Medical support | Count(healthcare)/pcs | Number of level II medical facilities within 800 m of the space point | |

| Central position | Dist(hospital)/km | Distance from space point to a tertiary hospital |

| Independent Variables | Coefficient | p | Tolerance | VIF | Filter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dist(CBD) | −0.194 | 0.000 | 0.820 | 1.219 | Pass |

| Dist(subway) | −0.313 | 0.000 | 0.680 | 1.471 | Pass |

| Count(shopping) | −0.054 | 0.031 | 0.548 | 1.829 | Pass |

| Count(leisure) | 0.131 | 0.000 | 0.637 | 1.569 | Pass |

| Count(healthcare) | −0.049 | 0.006 | 0.690 | 1.450 | Pass |

| Dist(hospital) | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.879 | 1.138 | Pass |

| Model Metrics | OLS | GWR | MGWR |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.202 | 0.509 | 0.578 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.200 | 0.487 | 0.541 |

| AICc | 3996.966 | 3384.927 | 3284.020 |

| Residual sum of squares | 1216.344 | 748.521 | 643.491 |

| Log-likelihood | −1991.446 | −1621.248 | −1505.965 |

| Residual Moran’s I | 0.375 | 0.192 | 0.072 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, S.; Chen, J.; Lu, S.; Qian, Y. Exploring the Pattern of Residential Space Differentiation in a Megacity’s Fringe Areas and Its Influence Mechanism: Insights from Beijing, China. Land 2026, 15, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010043

Hu S, Chen J, Lu S, Qian Y. Exploring the Pattern of Residential Space Differentiation in a Megacity’s Fringe Areas and Its Influence Mechanism: Insights from Beijing, China. Land. 2026; 15(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Suxin, Jiangtao Chen, Shasha Lu, and Yun Qian. 2026. "Exploring the Pattern of Residential Space Differentiation in a Megacity’s Fringe Areas and Its Influence Mechanism: Insights from Beijing, China" Land 15, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010043

APA StyleHu, S., Chen, J., Lu, S., & Qian, Y. (2026). Exploring the Pattern of Residential Space Differentiation in a Megacity’s Fringe Areas and Its Influence Mechanism: Insights from Beijing, China. Land, 15(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010043