Assessing the Functional–Efficiency Mismatch of Territorial Space Using Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Quanzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data Source

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

3. Research Framework and Methods

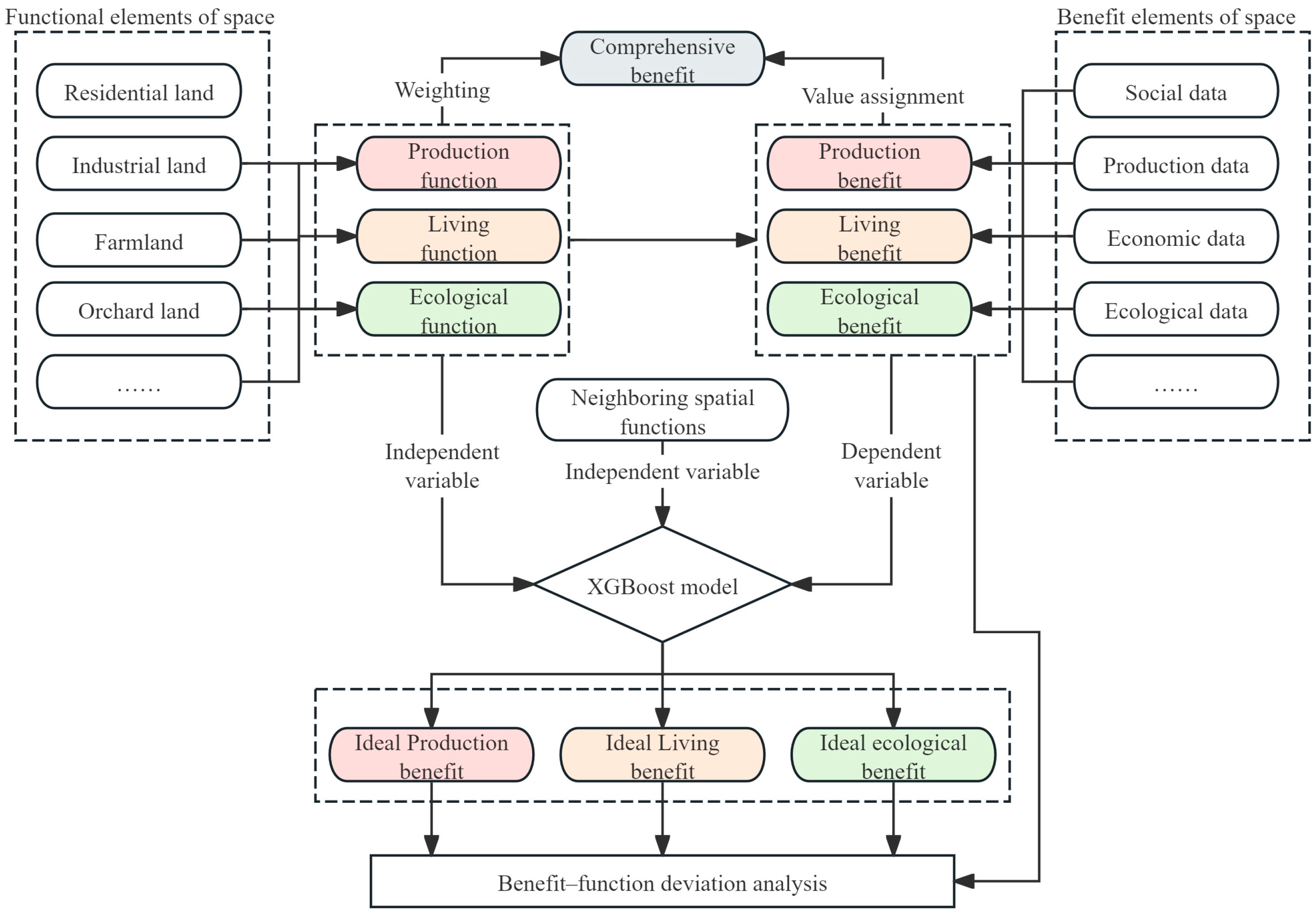

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Land-Use Function Identification

3.3. Spatial Efficiency Evaluation

3.4. Spatial Function–Efficiency Deviation Analysis Based on XGBoost

3.5. Spatial Feature Analysis

4. Results

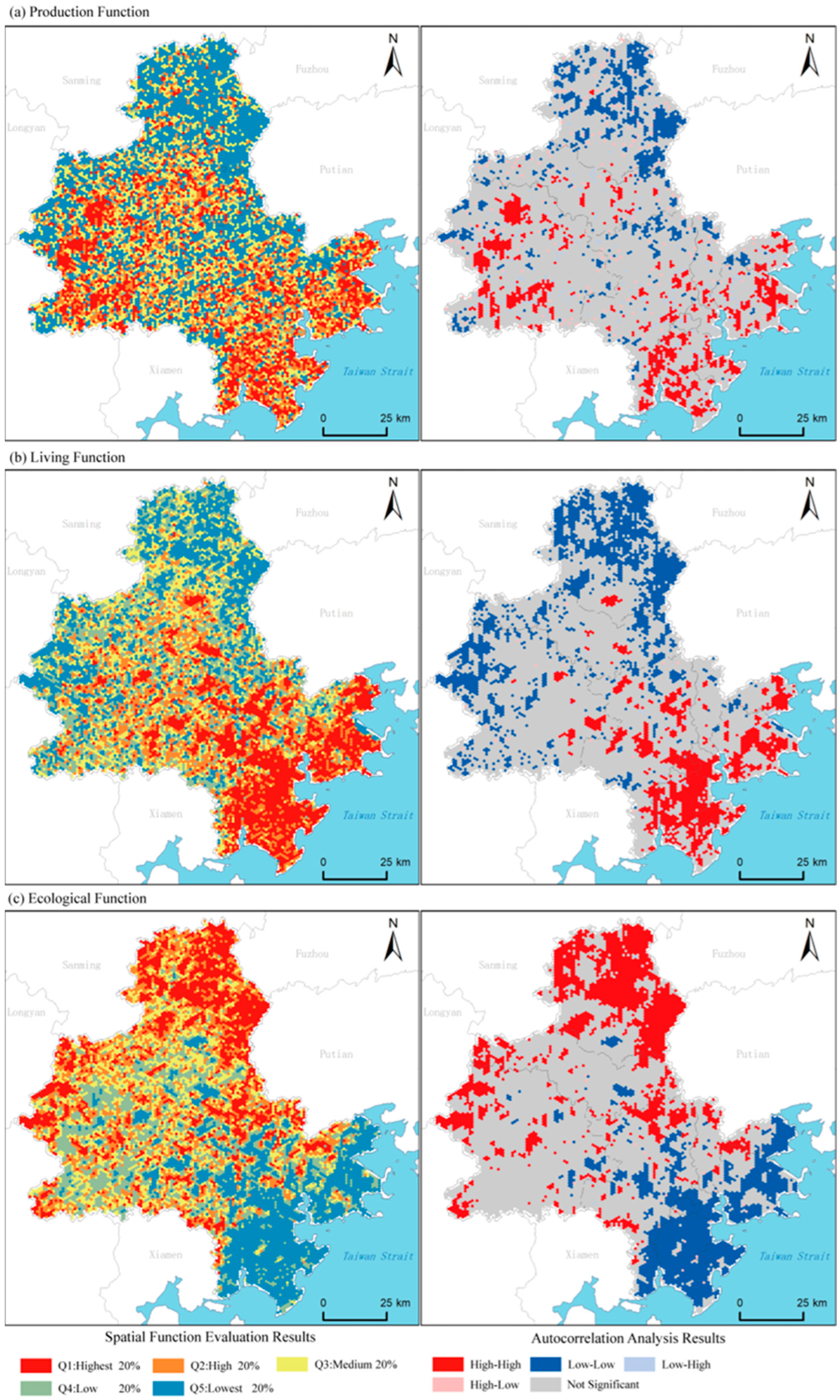

4.1. Spatial Characteristics of Territorial Functions in Quanzhou City

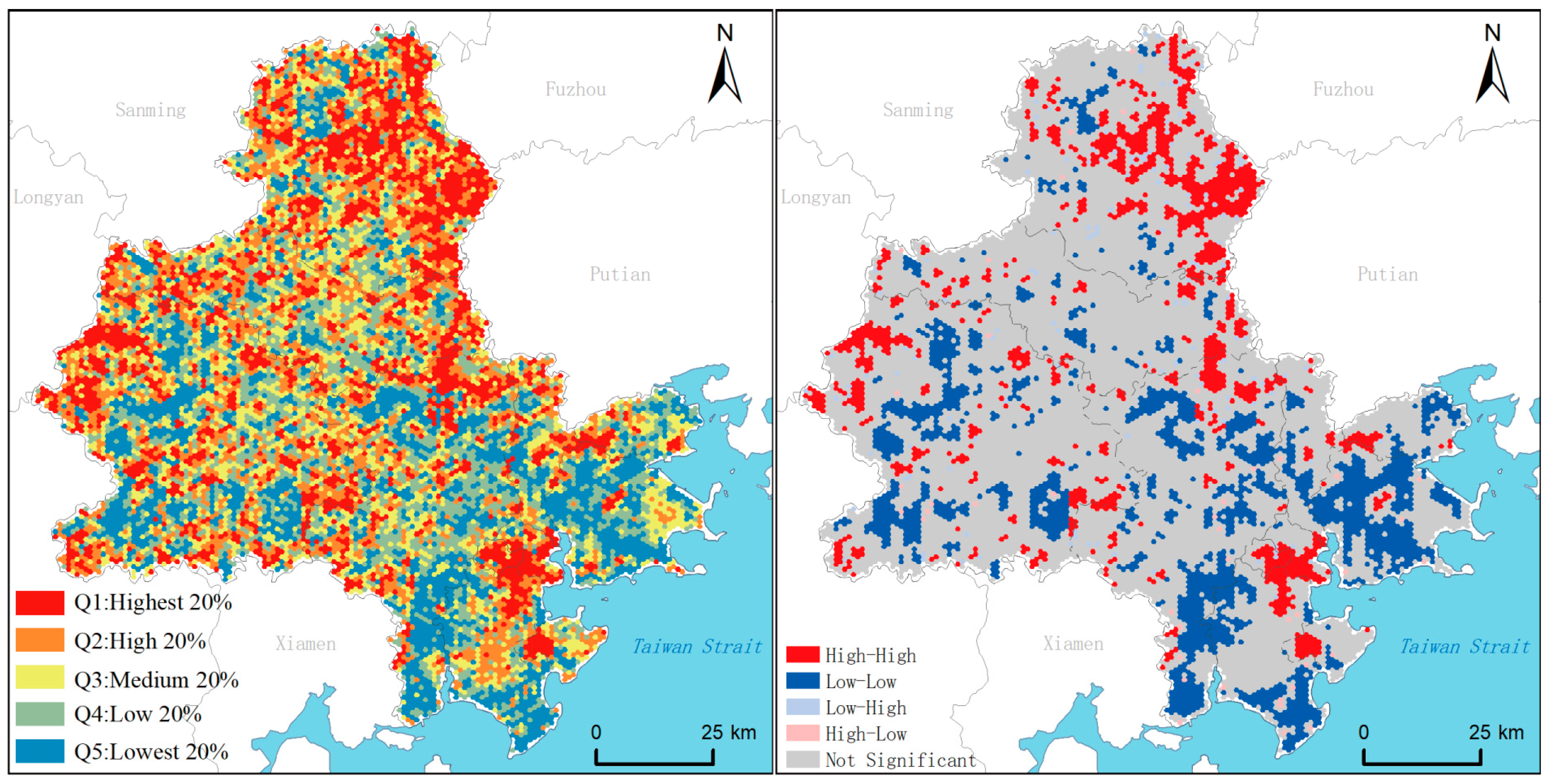

4.2. Spatial Characteristics of Territorial Efficiency in Quanzhou City

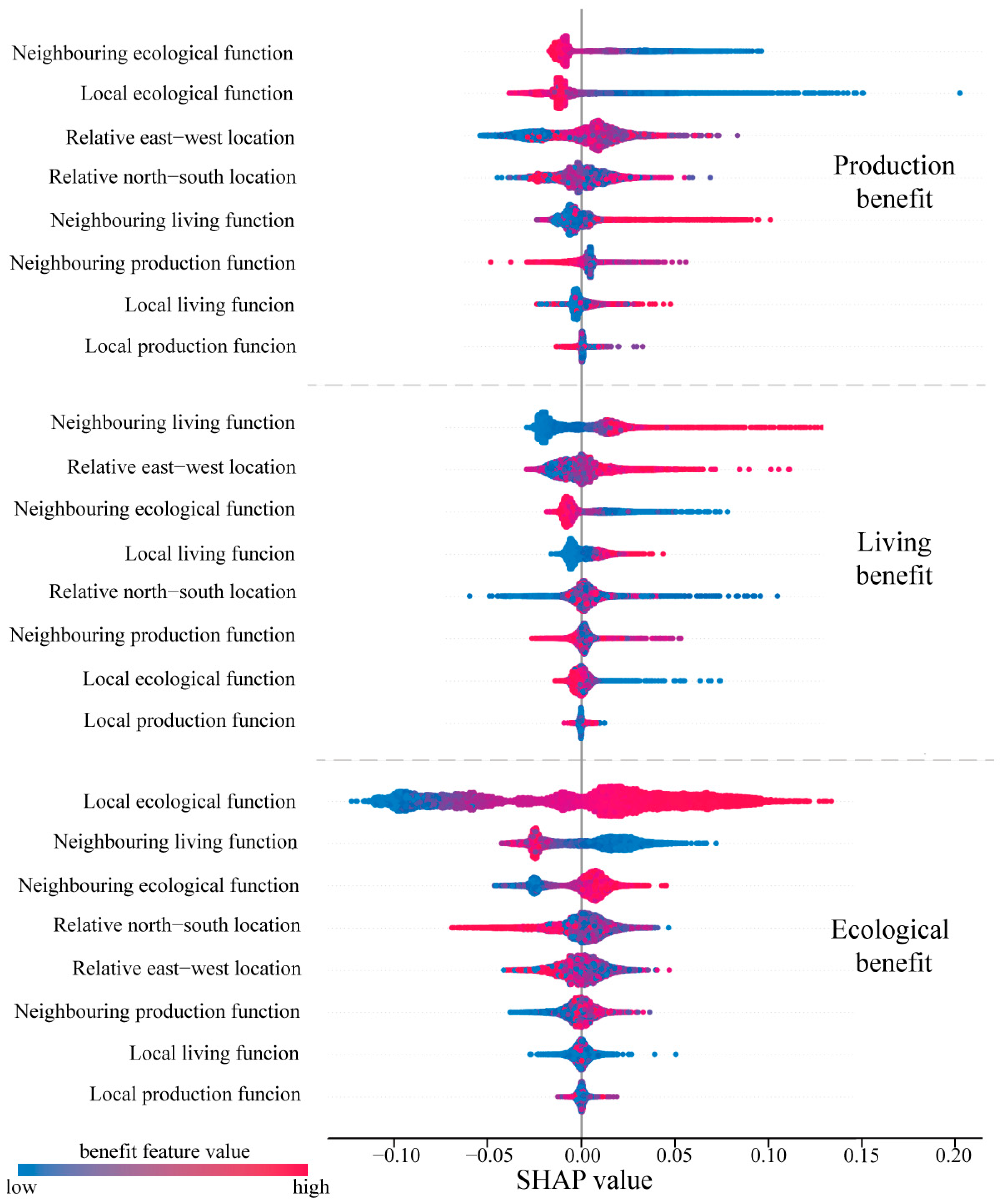

4.3. Prediction of Ideal Spatial Efficiency and Mechanism Analysis

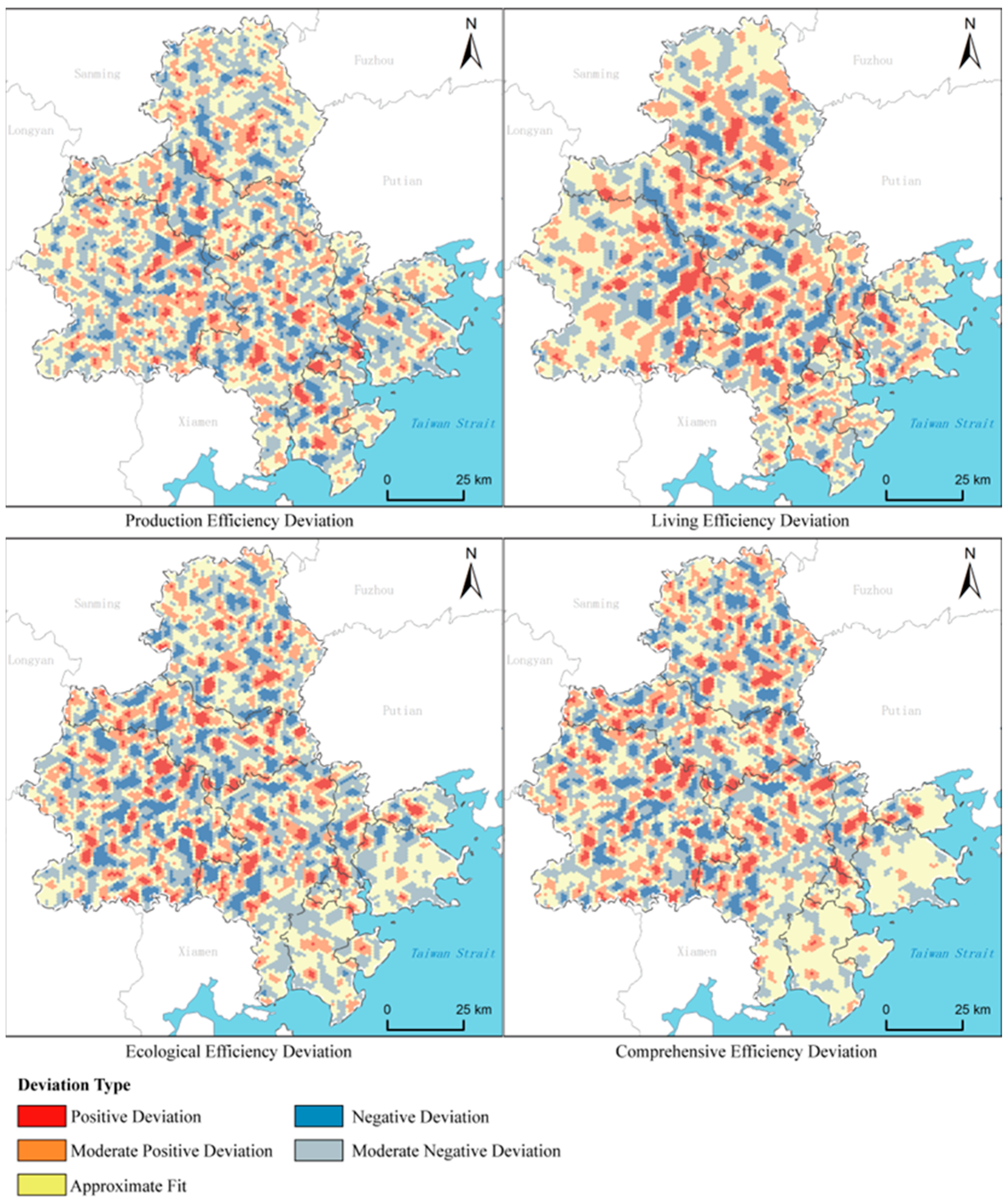

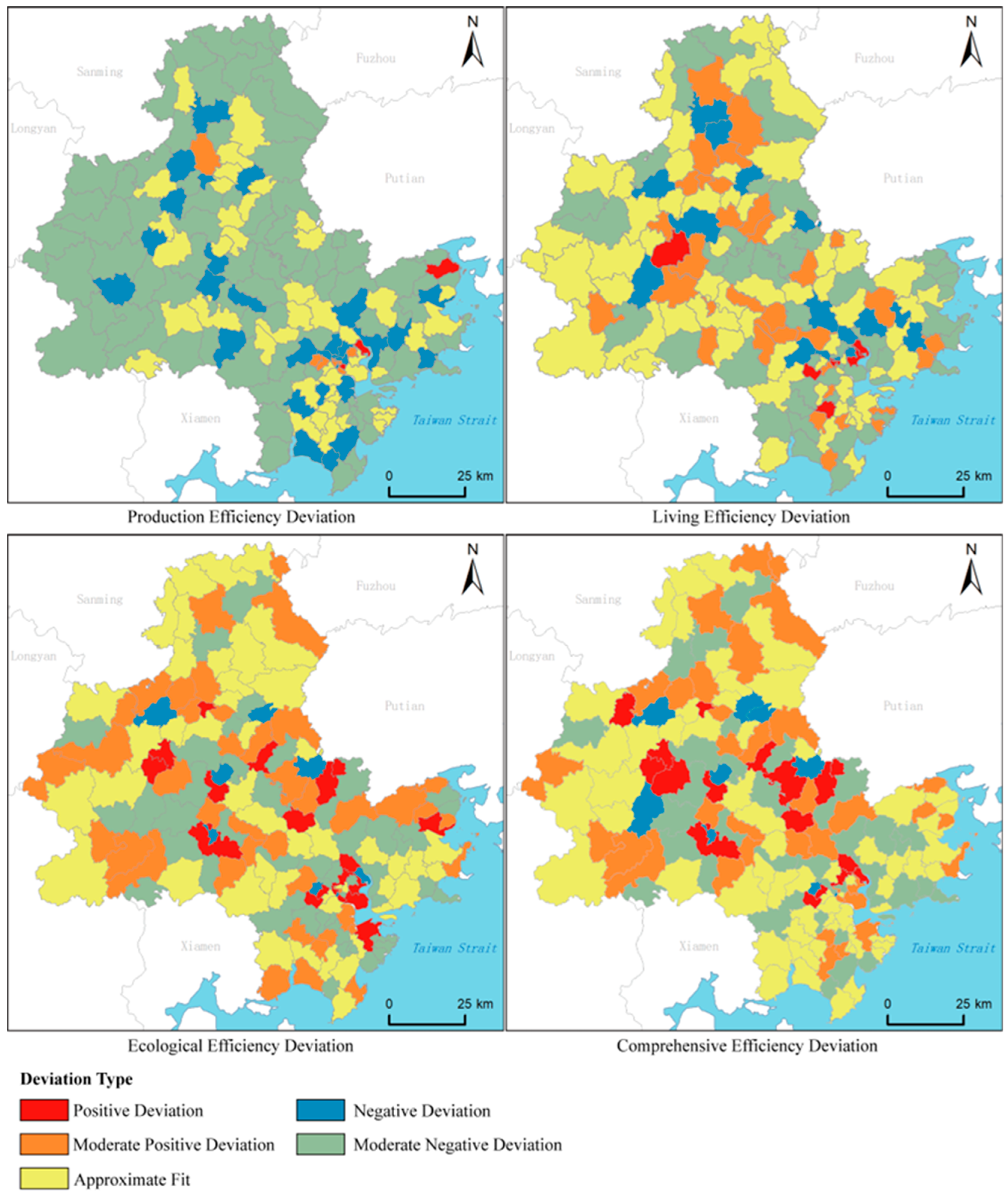

4.4. Spatial Deviation Results of Territorial Efficiency in Quanzhou City

- (1)

- The southern Quanzhou Bay zone demonstrated strong functional–efficiency alignment, especially in core urban districts with robust industrial and service bases. However, the outer peri-urban units showed deviations up to 0.03 lower than expected based on functional input levels, indicating uneven benefit realization within this high-growth region.

- (2)

- The central region, particularly the Shanmei Reservoir hinterland, formed a pronounced high-efficiency cluster. This subregion’s composite deviation averaged 0.19—almost double the citywide mean—highlighting the combined benefits of ecological quality and improving living service conditions.

- (3)

- The western mountainous zone exhibited stable positive deviations, supported by strong ecological resources and limited disturbance. Here, more than 80% of units recorded positive ecological or composite deviations.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W.; Zheng, S.; Sun, Y. Unraveling drivers of land use efficiency in rapidly urbanizing areas: A hybrid SBM-DDF and explainable machine learning framework. Habitat Int. 2025, 164, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zeng, H. Accurate identification and planning of land use functions in rapidly urbanizing areas based on multi-source data fusion. Cities 2025, 167, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lialia, E.; Prentzas, A.; Tafidou, A.; Moulogianni, C.; Kouriati, A.; Dimitriadou, E.; Kleisiari, C.; Bournaris, T. Optimizing Agricultural Sustainability Through Land Use Changes Under the CAP Framework Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Northern Greece. Land 2025, 14, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C.; Hu, B. Urban underground space value assessment and regeneration strategies in symbiosis with the urban block: A case study of large residential areas in Beijing. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 163, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Du, Z.; Bi, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, T. Ecological restoration zoning and its driving factors in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei based on landscape ecological risk and ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ao, Y.; Chai, B. Identification of key areas for ecological restoration based on ecological carrying capacity and ecological security pattern: A case study of Baoding. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Y. An integrated analysis framework for territorial space governance: Combining land use classification and functional evaluation toward spatial zoning. Habitat Int. 2025, 166, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, C.; Liu, Y. Detecting the contribution of transport development to urban construction land expansion in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China based on machine learning. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Yu, Z. Investigating the central place theory using trajectory big data. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, J.P.; Pires, A.J.G. A geographical theory of (de)industrialization. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2021, 59, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Wei, G.; Li, S.; He, B.-J. Does enhanced land use efficiency promote ecological resilience in China’s urban agglomerations? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 115, 108047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saakjans, D.; Gradinaru, S.R.; Hersperger, A.M. Planning open and green spaces in Europe: The importance of land-use regulations and their efficiency and equity objectives. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 264, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Wu, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, T. Understanding the relationship between population-land-industry inputs and function outputs of rural settlements: An efficiency-based perspective. Habitat Int. 2025, 159, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabašinskas, G.; Sujetovienė, G. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Supply and Demand for Ecosystem Services in Response to Urbanization: A Case Study in Vilnius, Lithuania. Land 2024, 13, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Spatial-temporal evolution and coupling coordination of land use functions across China using multiple-source heterogeneous data. Land Use Policy 2025, 155, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, Q.; Yang, P.; Xia, C. Dynamic coupling coordination of territorial spatial development intensity and comprehensive disaster-carrying capability: A case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 137, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up hierarchical detection of territorial spatial pattern based on multi-source heterogeneous data. Land Use Policy 2025, 158, 107757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariken, M.; Zhang, F.; Chan, N.W.; Kung, H.-T. Coupling coordination and spatio-temporal heterogeneity between urbanization and eco-environment along the Silk Road Economic Belt in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, H.; Chen, Y. Spatial correlation and interaction intensity between territorial ecological quality and new urbanization in the Nanchang metropolitan area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Hu, M.; Ma, X.; Li, X. Exploring the nexus between spatial configuration of urban agglomerations and land use efficiency: A bidimensional analysis considering transport network connectivity. Cities 2025, 167, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, C. Using social sensing to evaluate the effect of spatial planning: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration in China. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłos, M.J.; Staniek, M.; Sierpiński, G. Beyond the core: Method for assessing 15-minute city adaptation in diverse urban environments. Cities 2026, 168, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhu, H.; Xia, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, L. Spatial coupling coordination between land use efficiency and urbanization in the Chang-Zhu-Tan urban agglomeration, China. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 8642–8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, L. A new methodology to measure urban construction land-use efficiency based on a two-stage DEA model. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiao, W.; Li, L.; Ye, Y.; Song, X. Urban land use efficiency and improvement potential in China: A stochastic frontier analysis. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Fang, C.; Shu, T.; Ren, Y. Spatiotemporal impacts of urban structure on urban land-use efficiency: Evidence from 280 Chinese cities. Habitat Int. 2023, 131, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Wu, Q. Identification and planning response to inefficient urban and rural construction land use under the concept of relative performance. J. Urban Manag. 2025, 14, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yan, J.; Du, L. Spatial efficiency evaluation of subway station areas neighboring historic districts: Integrating transportation, culture, and place resources. Front. Archit. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Hu, C.; Liu, C. Spatial-temporal evolution and driving mechanism of urban land green use efficiency in the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Application of improved Moran’s I in the evaluation of urban spatial development. Spat. Stat. 2023, 54, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Xu, B.; Shi, X.; Li, R.; Chen, J. Spatial effects of rapid urbanization on land use efficiency in China under low-carbon constraints. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 174, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xie, A.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, P.; Ma, D.; An, Y.; Peng, G. Dynamic evolution and trend prediction of coupling coordination between urban and rural space utilization efficiency based on local and tele-coupling models. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Jin, X.; Frazier, A.E.; Yu, D.; Xia, C.; Hu, Z.; Hu, H. From local to national networks: Evolution and drivers of interprovincial linkages of construction land use efficiency in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 117, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, J.D.; Darling, L.E.; Locke, D.H.; Hardiman, B.S. Turning a new leaf: Social and land-use drivers of urban tree canopy change in the Chicago Metropolitan Area, 2010–2017. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 113, 128999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunsi, O.M.; Rienow, A. Examining urban expansion in Abeokuta through economic development clusters: A geospatial approach using Random Forest and Batty’s entropy. Geomatica 2025, 77, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Ge, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, H. Urban vitality and its driving factors in Zhengzhou’s main urban area based on multi-source data and XGBoost. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianoli, A. Unlocking Patterns in Urban Land Use Efficiency: A Global Analysis Using XGBoost and Bayesian Networks. Land Use Policy 2026, 160, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E.; Anselin, L.; Lee, S.; Koschinsky, J. Looking for Logic: The Zoning—Land Use Mismatch. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 152, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Spatial Distribution Dataset of Ecosystem Service Value in China; Resource and Environmental Science Data Center (RESDC), Chinese Academy of Sciences: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y. Identifying trade-offs and synergies among land use functions using an XGBoost-SHAP model: A case study of Kunming, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 172, 113330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Mu, H.; Chen, S. Production-living-ecological spaces and human-land relationships in poverty alleviation and relocation areas: Zhaotong City, Yunnan Province. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Jia, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X. Balancing urban expansion and ecological preservation: Simulation of production-living-ecological space dynamics in the Huaihe River Eco-Economic Belt. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tian, L.; Zhou, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhu, L. A comprehensive framework for assessing spatial conflict risk: A case study of production-living-ecological spaces based on a social-ecological system framework. Habitat Int. 2024, 154, 103218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Kang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Impact of land-use change on ecological environmental quality from the perspective of production-living-ecological space: The northern slope of Tianshan Mountains. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 83, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Cao, S.; Du, M.; He, Z. Aligning territorial spatial planning with the Sustainable Development Goals: A comprehensive analysis of production, living, and ecological spaces in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Ji, Z. Identification and spatio-temporal evolution of rural production-living-ecological space from the perspective of villagers’ behavior: A case study of Ertai Town, Zhangjiakou City. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, N. Research on Enhancing Urban Land Use Efficiency Through Digital Technology. Land 2025, 14, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-economic data | Township-level statistical yearbooks of Quanzhou City | Quanzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics |

| Land-use data | Shapefile | Quanzhou Bureau of Natural Resources |

| Nighttime light data | Raster, 742 m × 742 m | Earth observation group |

| Road network data | Shapefile | OpenStreetMap |

| Commercial and enterprise Points of Interest data | Shapefile | OpenStreetMap |

| Population data | Raster, 1 km × 1 km | LandScan Global Population Database |

| Housing market data | Shapefile | Beike Real Estate Platform |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | Raster, 1 km × 1 km | Geospatial Data Cloud |

| Net Primary Productivity (NPP) | Raster, 500 m × 500 m | National Aeronautics and Space Administration (https://www.nasa.gov/) |

| Ecosystem service value data | Raster, 1 km × 1 km | Resource and Environmental Science Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences [35] |

| Land-Use Type | Production Function Score | Living Function Score | Ecological Function Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated land | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Orchard land | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Forest land | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Grassland | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Wetland | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Agricultural facilities land | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Residential land | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Public administration and service land | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Commercial service land | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Industrial and mining land | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Storage land | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Transportation land | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Utility land | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Green space and open area | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Special-use land | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Inland water area | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Other land | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Evaluation Dimension | Indicator | Definition/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Production efficiency | Cultivation rate | Ratio of cultivated area to total farmland area |

| Agricultural output value | Agricultural output per unit of agricultural land | |

| Industrial rent | Average rent of shops and factory buildings | |

| Industrial | Density of commercial and enterprise points | |

| Living efficiency | Public service accessibility | Mean accessibility to healthcare, elementary schools, and elderly care facilities |

| Transportation accessibility | Average distance to bus stops | |

| Residential quality | Combined score of average second-hand housing and rental prices (higher value = better quality) | |

| Spatial vitality | Intensity of nighttime light | |

| Ecological efficiency | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | Vegetation coverage within the spatial unit |

| Net Primary Productivity | Utilization rate of solar energy by ecosystems | |

| Ecological purification value | Ecosystem’s capacity for pollutant purification | |

| Soil conservation value | Ecosystem’s capacity to prevent soil erosion and maintain fertility and structure |

| Efficiency Dimension | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Residual Moran’s I | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production efficiency | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.951 | −0.002 | 0.118 |

| Living efficiency | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.997 | 0.016 | 0.001 |

| Ecological efficiency | 0.048 | 0.035 | 0.804 | −0.005 | 0.005 |

| Major Influencing Factors (TOP 3) | Dominant Functional Drivers | Mechanism Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influencing Factor | Contribution | |||

| Production efficiency | Neighbouring living function | 0.025 | Production efficiency is mainly shaped by residential and productive conditions in surrounding areas, whereas local functional endowments exert relatively weak effects. | A spillover-dominant mechanism in which production activities tend to concentrate in areas supported by favorable living environments and adjacent productive bases. |

| Neighbouring production function | 0.007 | |||

| Relative east–west location | 0.007 | |||

| Living efficiency | Relative east–west location | 0.091 | Living efficiency is overwhelmingly influenced by inherited spatial structure, with supplementary contributions from neighboring production and living functions. | A strongly path-dependent mechanism characterized by high spatial autocorrelation and strong responsiveness to surrounding socioeconomic conditions |

| Neighbouring production function | 0.028 | |||

| Neighbouring living function | 0.018 | |||

| Ecological efficiency | Local ecological function | 0.204 | Ecological efficiency is dominated by intrinsic ecological endowment, strengthened by ecological and residential conditions in adjacent units. | An endowment-driven mechanism in which ecological performance primarily reflects natural conditions, with marginal gains from neighborhood ecological synergy. |

| Neighbouring ecological function | 0.041 | |||

| Neighbouring living function | 0.038 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ke, Z.; Wei, W.; Hong, M.; Xia, J.; Bo, L. Assessing the Functional–Efficiency Mismatch of Territorial Space Using Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Quanzhou, China. Land 2025, 14, 2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122403

Ke Z, Wei W, Hong M, Xia J, Bo L. Assessing the Functional–Efficiency Mismatch of Territorial Space Using Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Quanzhou, China. Land. 2025; 14(12):2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122403

Chicago/Turabian StyleKe, Zehua, Wei Wei, Mengyao Hong, Junnan Xia, and Liming Bo. 2025. "Assessing the Functional–Efficiency Mismatch of Territorial Space Using Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Quanzhou, China" Land 14, no. 12: 2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122403

APA StyleKe, Z., Wei, W., Hong, M., Xia, J., & Bo, L. (2025). Assessing the Functional–Efficiency Mismatch of Territorial Space Using Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study of Quanzhou, China. Land, 14(12), 2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122403