Co-Designing Accessible Urban Public Spaces Through Geodesign: A Case Study of Alicante, Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geodesign in Spatial and Accessibility Planning

3. Aims and Scope

- [RQ1] How can we conceptualise accessibility as a standalone system within the geodesign framework?

- [RQ2] How do different groups of stakeholders rank the importance of accessibility during a co-design process?

- [RQ3] To what extent does the geodesign process foster socio-spatial awareness and a sensitivity to equity and inclusion among architecture students?

4. Geographic Context of the Study: Alicante

Delimitation of the Case Study Area

5. Methodology: The Geodesign Approach

5.1. Behind the Scenes

5.1.1. Development of Representation, Process, and Evaluation Models: Conceptualising and Modelling the Accessibility System

5.2. Participatory Engagement Phase: The Workshop

5.2.1. Diagram Creation Phase: Individual Proposals

5.2.2. Role-Playing Phase: Group Proposals

5.2.3. Synthesising Proposals Through Synergy-Based Negotiation

5.2.4. Consensus and Final Decision-Making

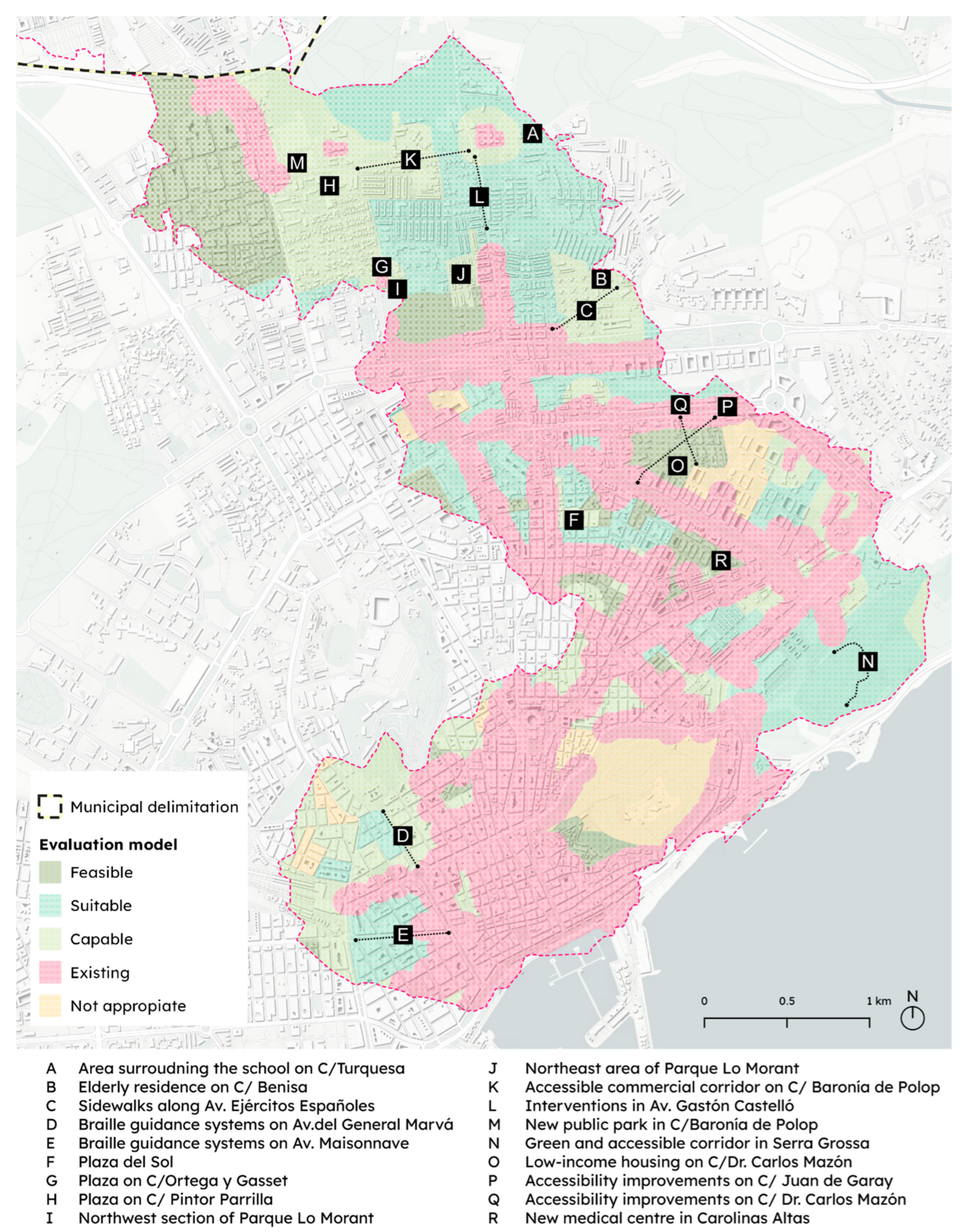

6. Results: Overview of Accessibility-Related Proposals

6.1. Diagram Production and System Overview

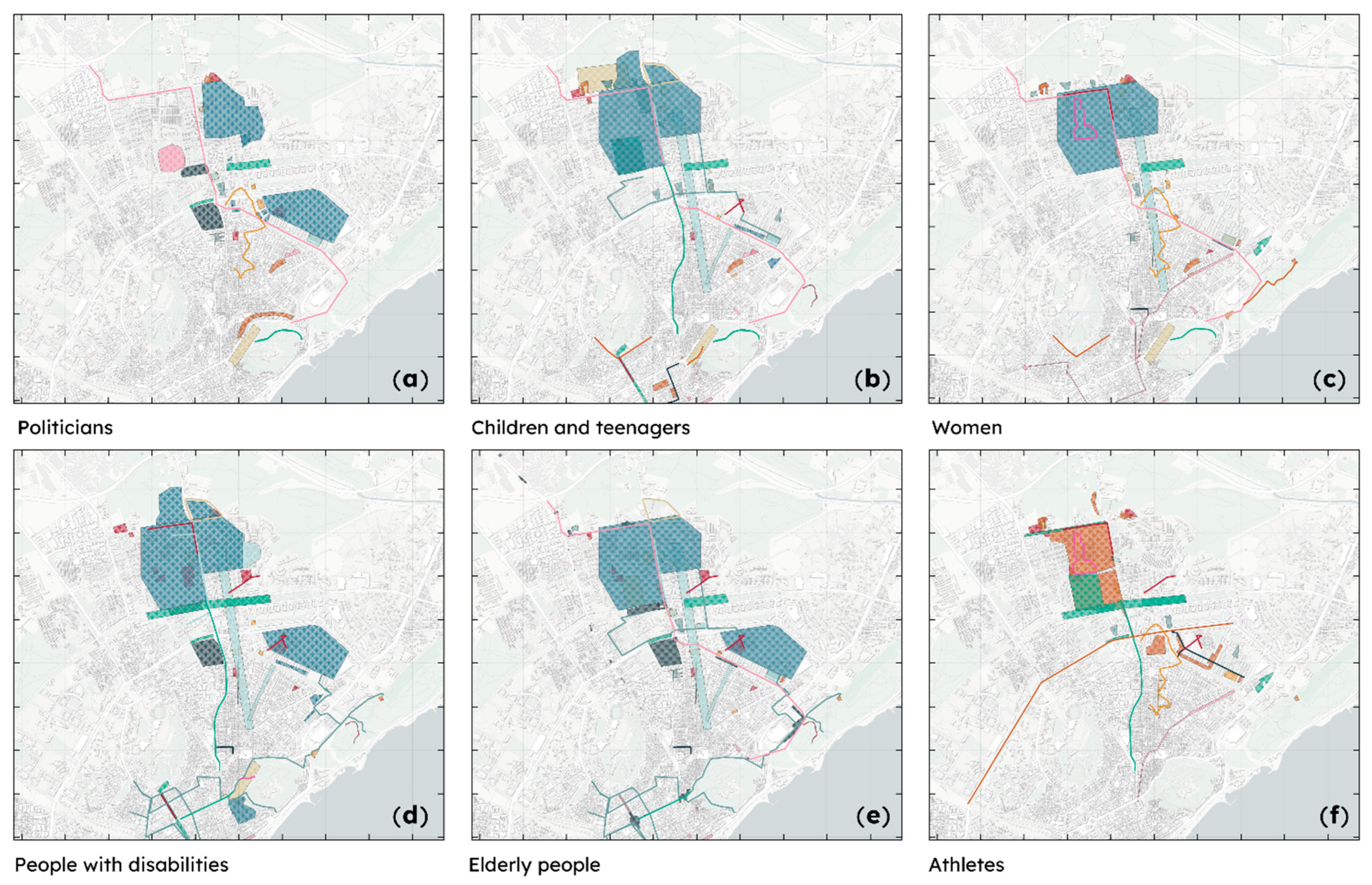

6.2. Stakeholder Role-Playing Outcomes

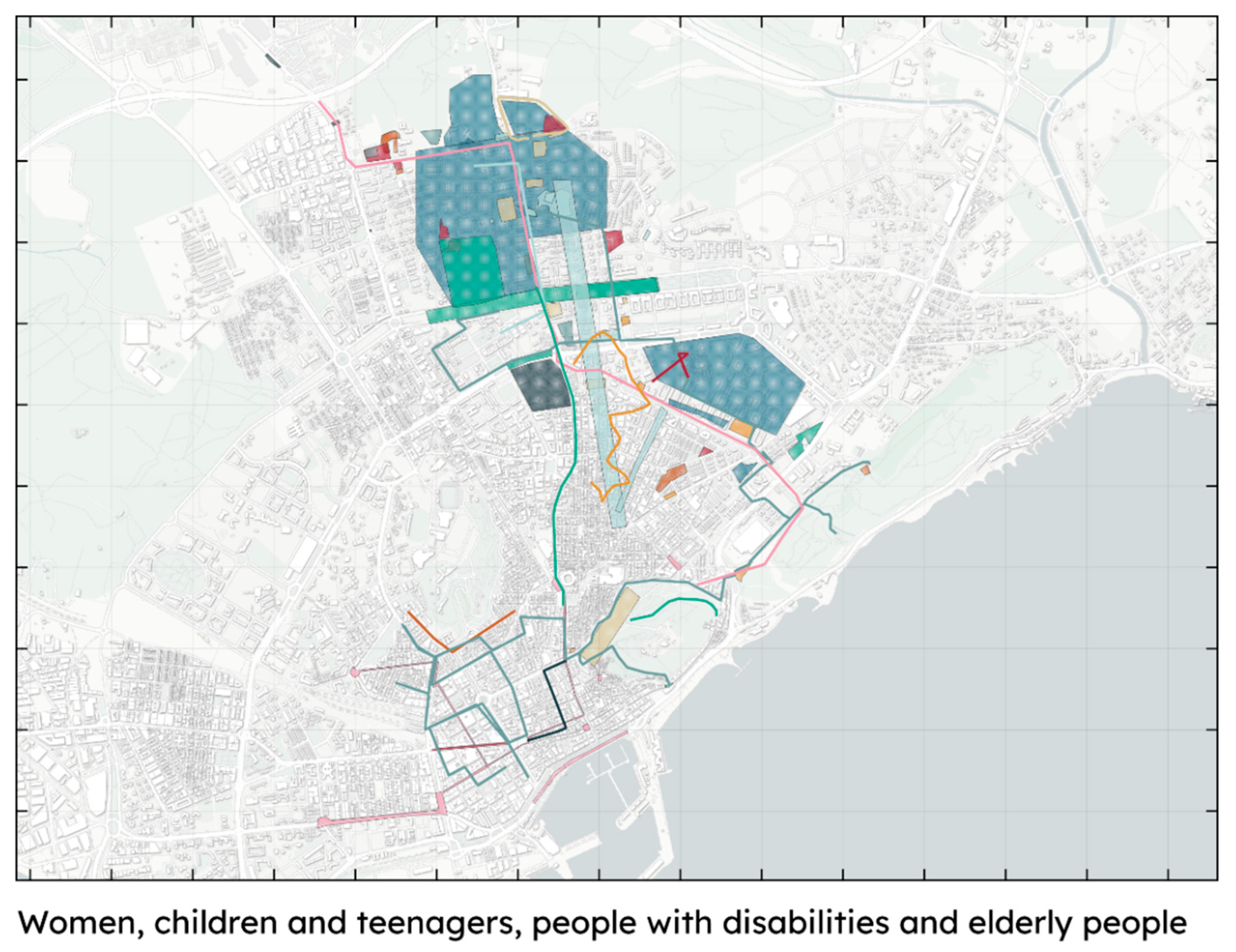

6.3. Synthesis and Negotiation Phases

6.4. Consensus and Final Decision-Making

7. Discussion

7.1. Accessibility as an Integrative or Isolated Design Objective

7.2. Spatial Distribution and Socio-Territorial Sensitivity

7.3. Pedagogical and Methodological Contributions

7.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| PSS | Planning Support System |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| PPGIS | Public Participatory Geographic Information System |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spanish National Statisctics Institute) |

| GVA | Generalitat Valenciana (Regional Valencian Community Government) |

| ICV | Instituto Cartográfico Valenciano (Valencian Cartographic Institute) |

References

- Lee, S.; Koschinsky, J.; Talen, E. Planning tools for walkable neighborhoods: Zoning, land use, and urban form. J. Archit. Plann Res. 2018, 35, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M.; Mesloub, A.; Alalouch, C.; Noaime, E. Reclaiming the Urban Streets: Evaluating Accessibility and Walkability in the City of Hail’s Streetscapes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Proyecciones Demográficas: INE y AIReF. Gobierno de España; MITECO: Madrid, Spain, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, U.; Rauws, W.S.; de Roo, G. Planning and Complexity: Engaging with Temporal Dynamics, Uncertainty and Complex Adaptive Systems. Environ. Plann B Plann Des. 2016, 43, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abujder Ochoa, W.A.; Iarozinski Neto, A.; Vitorio Junior, P.C.; Calabokis, O.P.; Ballesteros-Ballesteros, V. The Theory of Complexity and Sustainable Urban Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenbergh, N.; Ciuró, A.B.; Ahlers, R. Participatory Processes and Support Tools for Planning in Complex Dynamic Environments: A Case Study on Web-GIS Based Participatory Water Resources Planning in Almeria, Spain. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, A.; Arifin, K.; Ali, M.A.M.; Khairil, M. A Systematic Literature Review on Public Participation in Decision-Making for Local Authority Planning: A Decade of Progress and Challenges. Environ. Dev. 2023, 46, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğu, T.; Mengi, O.; Köse, S. Where Do Temporary Urban Design Interventions Fall on the Spectrum of Public Participation? An Analysis of Global Trends. Cities 2024, 152, 105164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataman, C.; Tuncer, B. Urban Interventions and Participation Tools in Urban Design Processes: A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis (1995–2021). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kang, E.; Shin, Y. Urban Regeneration and Community Participation: A Critical Review of Project-Based Research. Open House Int. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbi, V.; Ginocchini, G.; Sponza, C. Co-Designing the Accessibility: From Participatory Mapping to New Inclusive Itineraries Through the Cultural Heritage of Bologna. Eur. J. Creat. Pract. Cities Landsc. 2020, 3, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.; Smith, H.; Epstein, I.; Baljko, M.; Mcintosh, I.; Dadashi, N.; Prakash, D.N. Accessibility and Participatory Design: Time, Power, and Facilitation. CoDesign 2023, 19, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Siqueira, G.; Malaj, S.; Hamdani, M. Digitalization, Participation and Interaction: Towards More Inclusive Tools in Urban Design—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, M. Geodesign in the Planning Practice: Lessons Learnt from Experience in Italy. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 7, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somma, M.; Campagna, M.; Canfield, T.; Cerreta, M.; Poli, G.; Steinitz, C. Collaborative and Sustainable Strategies Through Geodesign: The Case Study of Bacoli. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Málaga, Spain, 4–7 July 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13379, pp. 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Patata, S.; Lisboa de Paula, P.; Mourão Moura, A.C. The Application of Geodesign in a Brazilian Illegal Settlement. Participatory Planning in Dandara Occupation Case Study. In Environmental and Territorial Modelling for Planning and Design; Leone, A., Gargiulo, C., Eds.; FedOAPress: Naples, Italy, 2018; pp. 673–685. ISBN 978-88-6887-048-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, C.J.; Hawken, S.; Ticzon, C.; Leao, S.Z.; Afrooz, A.E.; Lieske, S.N.; Canfield, T.; Ballal, H.; Steinitz, C. Breaking down the Silos through Geodesign—Envisioning Sydney’s Urban Future. Environ. Plan. B Urban. Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1387–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.A.; Mourão Moura, A.C.; Fernandes Araújo, B.M. Geodesign Teaching Experience and Alternative Urban Parameters: Using Completeness Indicators on GISColab Platform. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2022, 13379 LNCS, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.A.; Mourão Moura, A.C. Geoprocessing, Geodesign and Urban Parameters: Geoinformation and Co-Creation of Ideas in Urban Planning Teaching. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2024, 467 LNCE, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; von Haaren, C.; Vargas-Moreno, J.C.; Steinitz, C. Teaching Scenario-Based Planning for Sustainable Landscape Development: An Evaluation of Learning Effects in the Cagliari Studio Workshop. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6872–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jano Reiss, M.; Tchetchik, A. Facilitating Walkability in Hilly Terrain: Using the Geodesign Platform to Integrate Topographical Considerations into the Planning Process. Urban Book Ser. 2024, F2839, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F. Training Decision-Makers: GEODESIGN Workshop Paving the Way for New Urban Agenda. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2020, 12252, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Towards Geodesign: Repurposing Cartography and GIS? Cartogr. Perspect. 2010, 66, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Deal, B.; Larsen, L. Geodesign Processes and Ecological Systems Thinking in a Coupled Human-Environment Context: An Integrated Framework for Landscape Architecture. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, M.; Di Cesare, E.A.; Cocco, C. Integrating Green-Infrastructures Design in Strategic Spatial Planning with Geodesign. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R. Introducing Geodesign: The Concept; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Steinitz, C. A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design; Esri Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ballal, H. Collaborative Planning with Digital Design Synthesis. Ph.D. Thesis, UCL (University College London), London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Albert, J.; Vavages, A.; Pijawka, D.; Wentz, E.; Hale, M. Resilience-Based Adaptation in Data Scarce Areas: Flood Risk Assessment Using Geodesign in the Tohono O’odham Nation. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2025, 45, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, M.; Mourão Moura, A.C.; Borges, J.; Cocco, C. Future Scenarios for the Pampulha Region: A Geodesign Workshop. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, A.C.M.; de Oliveira, F.H.; Furlanetti, T.; Panceli, R.; de Oliveira, E.F.P.; Steinitz, C. Geodesign as Co-Creation of Ideas to Face Challenges in Indigenous Land in the South of Brazil: Case Study Ibirama La Klano. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Online, 1–4 July 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Nyerges, T.; Gallo, J.A.; Prager, S.D.; Reynolds, K.M.; Murphy, P.J.; Li, W. Synthesizing Vulnerability, Risk, Resilience, and Sustainability into VRRSability for Improving Geoinformation Decision Support Evaluations. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2021, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco, C.; Magalhães Fonseca, B.; Campagna, M. Applying Geodesign in Urban Planning: Case Study of Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. In Proceedings of the 27th International Cartographic Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 23–28 August 2015; UFU: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; pp. 929–940. [Google Scholar]

- Huskinson, M.; Serrano-Estrada, L.; Martí, P. Perceived Accessibility Matters: Unveiling Key Urban Parameters through Traditional and Technology-Driven Participation Methods. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key Issues and Research Priorities for Public Participation GIS (PPGIS): A Synthesis Based on Empirical Research. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 46, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Deal, B.; Orland, B.; Campagna, M. Evaluating Practical Implementation of Geodesign and Its Impacts on Resilience. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 5, 467–475. [Google Scholar]

- INE Demographic Information: Number of Eldery People per Census Section by Age. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Eurostat Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DEMO_PJANIND__custom_964289/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=599174db-325f-429b-87ba-6af6b18e9ca9 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- ICV Visor Cartogràfic de La Generalitat Valenciana: Grau d’accessibilitat Del Municipi. Available online: https://visor.gva.es/visor/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Alicante City Council Statistics Department Population Census Data of Alacant/Alicante—Diputación de Alicante. Available online: http://documentacion.diputacionalicante.es/4hogares.asp?codigo=03014 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Bosch-Checa, C.; Lorenzo-Sáez, E.; Haza, M.J.P.d.L.; Lerma-Arce, V.; Coll-Aliaga, E. Evaluation of the Accessibility to Urban Mobility Services with High Spatial Resolution—Case Study: Valencia (Spain). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch Checa, C. Análisis de Equidad Ambiental Entre Los Diferentes Barrios de La Ciudad de Valencia Mediante Datos de Dosimetría Pasiva y Otros Indicadores de Vulnerabilidad; The Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UITP The European Outlook: On Track with Light Rail and Tram Systems; UITP: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Chava, J.; Newman, P.; Tiwari, R. Gentrification of Station Areas and Its Impact on Transit Ridership. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2018, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.; Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P.L. Self-Selection in the Relationship between the Built Environment and Walking: Empirical Evidence from Northern California. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICV Visor Cartogràfic de La Generalitat Valenciana: Special Care Educational Centres. Available online: https://visor.gva.es/visor/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Strava Pedestrian and Cyclist Activity Data. Available online: https://www.strava.com/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Wikiloc Pedestrian and Cyclist Recreational Routes Data. Available online: https://www.wikiloc.com/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-59139-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine a Configurational Theory of Architecture; Space Syntax: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Campagna, M.; Steinitz, C.; Di Cesare, E.A.; Cocco, C.; Ballal, H.; Canfield, T. Collaboration in Planning: The Geodesign Approach. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2016, 35, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, F.B.; Erdoğan, S.; Yılmaz, M.; Ulukavak, M.; Şenol, H.İ.; Memduhoğlu, A. A new master plan for harran university based on geodesign. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-4/W6, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyerges, T.; Ballal, H.; Steinitz, C.; Canfield, T.; Roderick, M.; Ritzman, J.; Thanatemaneerat, W. Geodesign Dynamics for Sustainable Urban Watershed Development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 25, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, R.; Smith, A.; Orland, B.; Calabria, J.; Ballal, H.; Steinitz, C.; Perkl, R.; Mcclenning, L.; Key, H. Multiscale and Multijurisdictional Geodesign: The Coastal Region of Georgia, USA. Landscapes 2017, 19, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, T. Evaluating Accessibility for Transport Planning; Victoria Transport Policy Institute: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; De Jong, M.; Schraven, D.; Wang, L. Mapping Key Features and Dimensions of the Inclusive City: A Systematic Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R. Universalism, Universal Design and Equitable Access to the Built Environment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansern, N.; Philo, C. The normality of doing things differently: Bodies, spaces and disability geography. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2007, 98, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.E.B.; Chu, E.K.; Natekal, A.; Waaland, G. Institutional Designs for Procedural Justice and Inclusion in Urban Climate Change Adaptation. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, N.; Chen, J.-C.; Jarrott, S.; Satari, A. Designing Intergenerational Spaces: What to Learn From Children. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, Greece, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frediani, A.A.; Boano, C. Processes for Just Products: The Capability Space of Participatory Design. In The Capability Approach, Technology and Design; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Steiniger, S.; Poorazizi, M.E.; Hunter, A.J.S. Planning with Citizens: Implementation of an e-Planning Platform and Analysis of Research Needs. Urban. Plan. 2016, 1, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertman, S.; Stillwell, J. Planning Support Science: Developments and Challenges. Environ. Plan. B Urban. Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Description | Relevance to Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| Representation |

|

|

| Process |

|

|

| Evaluation |

|

|

| Change |

|

|

| Impact |

|

|

| Decision |

|

|

| Step | Description | Section | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [A] Behind the scenes | Organisation tasks and preparation of materials before the workshop | Section 5.1. | |

| [A1] | Development of representation, process, and evaluation models. Conceptualising and modelling the accessibility system |

| Section 5.1.1. |

| [B] Participatory engagement phase: the workshop | Workshop development with the participants that include both individual and collaborative tasks | Section 5.2. | |

| [B1] | Diagram creation phase: Individual proposals |

| Section 5.2.1. |

| [B2] | Role-playing phase: Group proposals |

| Section 5.2.2. |

| [B3] | Integration and synthesis of design alternatives: Synergies between groups |

| Section 5.2.3. |

| [B4] | Consensus and final decision-making |

| Section 5.2.4. |

| Version 02 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | Diagrams selected | |||

| Total | Accessibility diagrams selected | |||

| Number | Number | Percentage | Project | |

| Politicians | 32 | 3 | 9% | A F O |

| Children and teenagers | 66 | 9 | 14% | D E H I Q L M N P |

| Women | 60 | 3 | 5% | A L R |

| People with disabilities | 69 | 18 | 26% | A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R |

| Elderly people | 82 | 11 | 13% | B C D F G H I K L N R |

| Athletes | 51 | 9 | 18% | A C H I K L M P Q |

| Disabled People | Politicians | Elderly | Women | Athletes | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disabled people | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | |

| Politicians | − | − − | − − | − − | − | |

| Elderly | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | |

| Women | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Athletes | − − | − | + | − − | + | |

| Children | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | − |

| Negotiated Design: Agreements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | Diagrams selected | |||

| Total | Accessibility diagrams selected | |||

| Number | Number | Percentage | Project | |

| Women, children and teenagers | 53 | 3 | 6% | A M R |

| People with disabilities and elderly people | 62 | 15 | 24% | A B C D E F G H I M N O P Q R |

| Politicians and athletes | 33 | 3 | 9% | A H F |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huskinson, M.; Bernabeu-Bautista, Á.; Campagna, M.; Serrano-Estrada, L. Co-Designing Accessible Urban Public Spaces Through Geodesign: A Case Study of Alicante, Spain. Land 2025, 14, 2072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102072

Huskinson M, Bernabeu-Bautista Á, Campagna M, Serrano-Estrada L. Co-Designing Accessible Urban Public Spaces Through Geodesign: A Case Study of Alicante, Spain. Land. 2025; 14(10):2072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102072

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuskinson, Mariana, Álvaro Bernabeu-Bautista, Michele Campagna, and Leticia Serrano-Estrada. 2025. "Co-Designing Accessible Urban Public Spaces Through Geodesign: A Case Study of Alicante, Spain" Land 14, no. 10: 2072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102072

APA StyleHuskinson, M., Bernabeu-Bautista, Á., Campagna, M., & Serrano-Estrada, L. (2025). Co-Designing Accessible Urban Public Spaces Through Geodesign: A Case Study of Alicante, Spain. Land, 14(10), 2072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102072