1. Introduction

Tourism destinations around the world are facing social and ecological changes that will worsen over the coming years [

1,

2]. Tourism has much potential to make regions more resilient and to assist them in coping with these changes [

3]. A region can benefit from tourism in economic terms, through an increase in jobs, wellbeing and livability [

4]. Conversely, because a tourism destination is dependent upon attractive landscapes and highly biodiverse habitats, tourism managers should seek to protect landscapes to ensure the tourists keep coming [

5]. Nevertheless, in practice, balancing nature protection and tourism development often remains challenging given the disruptive effects tourism can also have on communities and landscapes [

6].

In this paper, it is argued that synergy between tourism development and nature protection is a precondition to building resilience in regions. Synergies are about striving for win-win situations by balancing the twin goals of nature protection and economic development. Focusing on synergies helps in overcoming an excessive focus either on nature protection or on economic development. When tourism and nature are balanced, this helps build social-ecological resilience in an area. Resilience is a concept that has been widely discussed, but its practical application remains limited [

2]. In practice, the extent to which synergies are acknowledged and activated is very much dependent on the effectiveness of decision-making processes. Therefore, decision-making processes and how these have been changing over time are the main focus in this paper.

The role of policy and how local stakeholders act are important in steering the course of development [

7]. Despite the need for win-win and balance, the emphasis in policy is often either on economic development or on the protection of landscapes. This results in outcomes that are conflicting rather than mutually strengthening. Opportunities for synergies between tourism and nature are generally overlooked [

4,

8].

To help policy makers manage tourism and nature better and avoid undesirable outcomes, this paper provides recommendations to improve decision-making. To do this, it was necessary to identify the factors that enable and constrain the synergies between tourism and landscape. The extent to which synergies are likely to be acknowledged and acted upon is related to the quality of the decision-making processes. It is also important to assess the institutional context [

9] from different angles, and to understand how policy has developed over time, how public opinion has changed, and how multilevel governance was and is arranged. To discuss the concept of synergetic interactions in tourism, we report on a case study of Terschelling, a Dutch island in the UNESCO World Heritage Wadden Sea. The island is renowned for its outstanding landscapes, and is an important tourism destination. This current paper is based on our previous papers [

3,

10,

11,

12], however, it goes beyond the previous papers by offering overarching policy recommendations.

2. Towards Resilient Regions

Striving for synergies between tourism and landscape can help build the resilience of regions and tourism destinations [

10]. Resilience is a key concept in social-ecological system (SES) thinking and implies that a system is able to cope with and positively adapt to future social and ecological changes [

13,

14]. In order to progress towards resilient regions, there is a need to understand the way tourism and landscape interact, and how these interactions can be improved to find a good balance between economic development and nature protection [

15,

16].

The concept of synergies is elaborated by Heslinga et al. [

3] and refers to situations of mutual gains in which the interactions between the elements of a system combine in ways that result in a sum-total that is larger than the sum of its parts [

17]. The general idea is that synergies steer away from trade-offs between economic development and nature protection, where one is chosen over the other, and instead look for win-win outcomes. A situation with an extreme focus only on nature protection leads to the exclusion of human activities, something that might be regarded as socially undesirable. An extreme focus on economic development will likely lead to environmental degradation, which is ecologically undesirable. Synergetic interactions are about win-win situations, meaning that nature protection and economic development are not conflicting, but can help strengthen each other [

11]. When tourism-landscape interactions are balanced, this helps to build social-ecological resilience in a region [

1,

2,

3].

The extent to which synergies are acknowledged is dependent on policy and decision-making processes [

18,

19,

20,

21]. This is because the role of policy and how stakeholders act are important in steering development. To make future policies on tourism and nature, it is vital to understand how decisions are made, and have been made in the past [

7]. Whether synergies actually contribute to resilience is affected by how policy has changed over time, the fluctuating nature of public discourse, and the extent to which all stakeholders (despite differing interests and power relations) are involved in governance processes [

22,

23]. These three issues are analyzed in this paper.

3. Terschelling as an Exemplar for Analyzing Tourism-Landscape Interactions

It is generally accepted that the use of real-life examples can assist in explaining a concept [

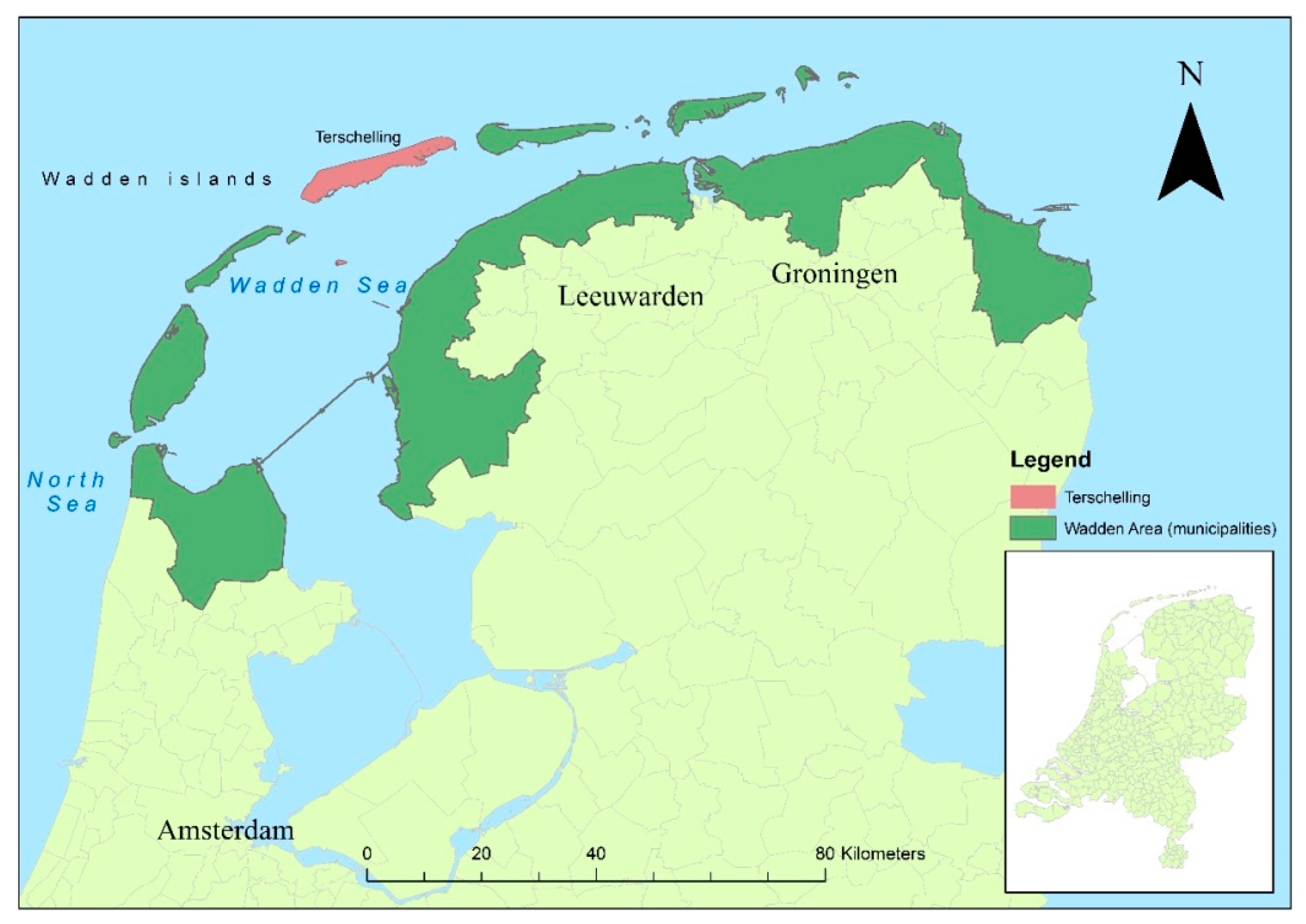

24]. Therefore, this paper uses of the case of Terschelling (see

Figure 1), the Netherlands, to discuss tourism-landscape interactions. Terschelling is an island located in the Wadden Sea region, a UNESCO World Heritage site in the north of the Netherlands. The Wadden is renowned for its ecological qualities (birds, seals, etc.) and highly-valued landscapes (mudflats, saltmarshes, dunes, forest). Due to its attractiveness, tourism has been increasing over the past decades and is now a significant activity in the Wadden [

25]. Each year, the area is visited by many tourists who enjoy hiking, bicycling, swimming, sunbathing, birdwatching and other activities.

Taking Terschelling as an example is relevant because the twin goals of economic development and nature protection come together here and potentially clash. Terschelling is successful as a tourism destination, but is highly dependent on nature and its beautiful landscapes. There are many stakeholder groups with an interest in Terschelling that seek to be involved in decision-making processes relating to nature, tourism, and the development of the island.

5. What Influences Tourism-Landscape Interactions

To determine to what extent the idea of synergy works in practice, a series of key factors that influence synergetic interactions between tourism and landscapes were identified based on the research on Terschelling. These key factors can be grouped into those that relate to: (1) ‘policy’, which refers to things like path dependencies in the historical institutional context, fluctuations in policy orientations, the recent increase in synergies in policy, and clear rules and regulations; (2) ‘public discourse’, e.g., short-termism, the influence of environmental summits and international declarations on public debate, the cyclical way synergies occur within public debates; or (3) ‘governance processes’, e.g., inclusion of all stakeholders, an attitude of openness and effective communication between all stakeholders, the changing attitude of influential stakeholders, flexibility to enable innovation, and the lack of capacity of local government. These factors can each be constraining and/or enabling.

5.1. Policy

The historical institutional context in which future decision making takes place is important in that it can enable or constrain synergetic interactions between tourism and landscape. Because of path dependency, this can be highly influential in determining the future course of the interactions between tourism and landscape. This current institutional context is a product of past policy, which potentially could hinder other development trajectories. Looking at the institutional context from an historical perspective provided an indication of how the interactions between tourism and landscape have been managed. It can also indicate which opportunities and threats affect the course of future developments.

The content analysis of policy document revealed that one constraining factor is the fluctuating nature of policy orientations between an emphasis either on economic development or on nature protection. This past black-and-white thinking does not fit with the idea of a tourism destination being a social-ecological ensemble. Given that synergies are desirable, a focus on either economic development or nature protection is a constraining factor.

From the document analysis and interview data, it became clear that, in the past, creating integrated policy was difficult and acknowledgement of possible synergies was limited. However, the content analysis also showed that this has been improving over time. Despite this increase in the attention given to synergies, the conventional silo-based way of designing policy is subject to path-dependency and is not easy to change. From an SES perspective, a more integrated policy is desirable, as this could enable synergetic interactions between tourism and landscape.

5.2. Public Opinion

Public opinion is a crucial factor that can constrain or enable synergetic tourism–landscape interactions. One constraining factor is the fluctuations in public thinking over time between economic development, nature protection, and synergies. Short-term economic thinking is another key factor that constrains synergetic thinking. The content analysis of newspaper articles revealed that the prevailing economic situation strongly influences public opinion in relation to the need for nature protection and economic development. At some points in time, nature protection became more important. From the interviews, it became clear that this change in focus was usually prompted by external (and often macro) triggers, such as a perceived global need to care for nature, landscape and the environment. Reflecting on SES theory, it can be concluded that Terschelling is part of a multi-scalar system [

28], in which macro events at higher levels influence lower levels. For tourism destinations, it is important to realize that issues do not only occur at the local level, but also that social and ecological changes take place at higher levels, and that these changes could have consequences for developments at the lower level.

The extent of thinking in terms of synergies on Terschelling has been increasing over time. The content analysis of newspaper articles found that the factors that have influenced the development of synergies are ‘collaboration‘, ‘working together’ and ‘being involved’. Recently, ‘thinking about sustainability’ has also become more pronounced. Our analysis found that synergies were also present at various times in the past. The resilience literature states that it is not always possible to steer everything in the desired direction [

29,

30,

31]. Situations can be very persistent and therefore adapting to change can take a long time. However, when a tipping point is reached, a situation can also change very suddenly. Steering towards synergetic tourism-landscape interactions for building social-ecological resilience is a matter of timing and momentum.

Another observation from our research is that policy often lags behind public opinion and societal changes. The debate about these issues on Terschelling was often ahead of policy interventions. The Wadden area became prominent as national nature area only in the 1970s, whereas our data from the content analysis and interviews indicated that there were already protection initiatives going on at the local level since the 1950s.

To have effective protection, it is essential to have strong connections between people and nature areas [

28]. Of course, tourism has social and ecological impacts on nature areas, but people also highly appreciate these areas and feel strongly connected to them. As argued in this paper, tourism can contribute to strengthening this connection between people and nature. Tourism can assist in the protection of nature areas by helping them become an important societal issue and consequently to be positioned on the political agenda. This observation indicates that there is a need to further combine SES theory with social and political factors as important forces that can affect the course of development [

32,

33].

5.3. Governance Processes

Some key factors with regard to partnerships in governance processes and the way stakeholders interact with each other were identified. The extent to which stakeholders are included in governance processes is of great importance. It was seen that greater inclusiveness of stakeholders led to increased public support. Civilians and entrepreneurs want to be informed, but they also have ideas for future developments and are often willing to take part in nature protection activities. An attitude of openness, effective communication, and good collaboration between all relevant stakeholders are essential for facilitating synergies between tourism and landscape. Individuals and organizations, as well as the way they collaborate, are highly influential [

34].

The attitude of the national forest management agency, Staatsbosbeheer (SBB), was a constraining factor, because, as a large landowner, this agency was very powerful, and in the past, it operated in a top-down manner. However, their attitude and manner of engagement changed over time, and they have become accepting of synergetic tourism-landscape interactions. The reason for this shift was that there was the realization within the organization that locking-up nature areas was not socially desirable. SBB realized that it needed to have public understanding and support of its mission and associated activities. From our analysis, it became clear that an attitude of openness and effective communication with all stakeholders were important conditions to achieve a social license to operate [

35]. It was also found that local government has the potential to facilitate synergies at the local level. Nevertheless, based on interview data, it was observed that local governments often struggle with this, because they lack resources and often choose to be risk-averse in their decision making. Consequently, there are only limited initiatives that acknowledge synergies between tourism and landscape proposed, and these are often obstructed.

Opportunities for synergies can be constrained at the local level. Regulations from higher governmental levels also constrain possibilities for synergies at the local level. Nevertheless, how these regulations are implemented at the local level can promote or retard specific opportunities. However, without clear decision making by local government, synergetic interactions are constrained even further. A necessary factor that was mentioned is to have clear rules and regulations, but there is also a need to have room for innovation and adaptation to changing circumstances. At the local level, a more flexible attitude could provide more opportunities for enabling synergies between tourism and landscape. SES theory advocates for a multilevel system in which the higher levels influence the local level, and vice versa. From our example, it was evident that, given the multilevel system, it essential that solutions and opportunities for synergy be strived for at the local level.

Allowing some flexibility in policy implementation is important, because a tourism destination such as Terschelling needs to have the capacity to adapt and to cope with the changing demands of tourists. Tourism is a sector that changes rapidly, because the demands of tourists are fickle [

11,

36]. Whenever a tourism destination is unable to innovate, it runs the risk that tourists will prefer other destinations. Not being able to cope with these changes could mean that many local stakeholders would miss out on the benefits that can be derived from tourism. The observations from our case study showed that providing flexibility for synergies and multi-functional use of space where different functions can be connected to each other need to be considered. In an SES perspective, the world is constantly in flux, and therefore to cope with changing circumstances, a system requires flexibility to build social-ecological resilience. Conversely, the policy response is typically stubbornness, persistence and maintaining the status quo [

13].

The final factor that influenced synergetic interactions on Terschelling was a difference between temporal and non-temporal land use activities. Flexibility in land use enables synergetic interactions to occur, partly because it enables experimentation. Tourism entrepreneurs, for example, can work together with nature protection organizations to provide short-term tourism activities in nature areas. The case study showed that recently more flexibility was provided by the major land owners, notably SBB. Through experimentation and learning-by-doing, opportunities for synergies were revealed. What can be learned from all this is that, apart from setting rules and regulations, it is crucial to build trust between stakeholders. Flexibility regarding land use can be difficult. Real estate developments, for example, were problematic because they lock up the land for decades or even permanently and may cause problems into the future.

6. Eight Policy Recommendations for Stimulating Synergy

We provide eight policy recommendations to help facilitate synergies between tourism development and nature protection. These recommendations are based on the results of the research undertaken on Terschelling. Since every tourism destination is different (i.e., context dependent), these recommendations are not panaceas that will necessarily work in every context, instead they are suggestions to consider. Thinking about these recommendations will help policy makers and planners understand and guide the process of stimulating synergy.

1. Understand the historical institutional context of a region

It is vital for policy makers and planners to understand the local context in which they operate. Looking back on how policy and public discourse has been evolving can make policy makers aware of the obstacles and opportunities in making effective future policies. This can help policy makers identify path-dependencies that may impede alternative policy options. Content analysis [

10,

11] can be a user-friendly tool to systematically analyze the way the institutional context has been changing over a long time period.

2. Strive for integrated policy aimed at synergetic interactions

The starting point of this paper was that tourism and landscape are highly interlinked and should be managed that way. For policy makers, this implies a different way of protecting nature areas. Especially for nature areas that are in the vicinity of places where people live, work and play, it is impossible to fully close them off from human influence. For people to support nature protection, they need to know what is being protected and why, and ideally, they need to personally experience the area [

37,

38]. To balance the social and ecological aspects, whenever possible, policy makers are recommended to develop integrated policies, taking the synergetic interactions between tourism and landscape into account.

3. Gain an overview of all stakeholders

To get an overview of the relevant stakeholders, how they can be categorized and the way they interact with each other, stakeholder analysis [

12] is helpful. In particular, the influence-interest matrix assists policy makers in making strategic choices for dealing with the different type of stakeholders. The matrix assists in making interactions more effective; as it suggests where to intervene in interactions that are limiting or stimulating synergies.

4. Include all stakeholders

The involvement of all stakeholders is essential to generate public support for the proper management of tourism-landscape interactions. There can be differences in the extent to which stakeholders are involved, but they should, at the very least, be informed about future developments. Potential decisions need to be explained properly and stakeholders need to have opportunities to share their views on them. Connecting with different stakeholders is not only about legitimatizing decisions, it is necessary for understanding each other’s perspectives and finding common ground and shared values. In addition, involving local inhabitants and entrepreneurs can be beneficial, because they often have interesting ideas and are willing to contribute positively to deliberative processes. Local knowledge can be of great use for policy makers.

5. Develop a shared story

The intention to develop a shared vision is a useful mechanism to get all stakeholders to engage in a participatory process. Such participation can build trust, commitment and willingness to take collective action. It can also remove the prejudices, fear and myth that create barriers and conflict. However, given that stakeholder group have their own interests, when everyone strives to achieve their own self-interest, this will negatively affect the collective goal. To create a shared vision, it is necessary to develop a story together, that all stakeholders can connect to. This storytelling creates direction for all stakeholders and is helpful in making choices. Two important conditions for this are an attitude of openness and transparent communication by all stakeholders [

39].

6. Co-create a clear vision for the future

It is recommended that policy makers and other stakeholders co-create a clear vision for the future that is aimed at synergetic interactions between tourism and landscape. Clarity in the rules and regulations is needed, as this decreases uncertainty about future policy directions for stakeholders. Rules and regulations that are unclear, confusing or conflicting can lead to risk-averse behavior by stakeholders. Interestingly, this seems to apply to local governments as well. They are often challenged by the many regulations they have to comply with and they often lack the resources and capacity to interpret and apply policy.

7. Allow for flexibility in the local implementation

Although clarity in rules is desirable, policy makers are also recommended to allow some flexibility in the implementation of initiatives at the local level. Rules and regulations from higher government levels restrict the flexibility at the local level, but opportunities for finding flexibility lie in implementation at the local level. Having space for innovation is crucial for a tourism destination [

40], as the demands of tourism are volatile. A tourism destination needs to be able to cope with these changing demands. Creating space for development and the amount of freedom that should be given to entrepreneurs is something that needs to be continually discussed. Especially with regards to land use, flexibility is highly recommended. For non-temporal forms of land use, such as the development of new real-estate projects, it is recommended to be cautious and risk-aversive. Real-estate related issues are a challenge for local governments, because ownership of land is fragmented and house price tend to increase rapidly in popular tourism destinations.

8. Dare to experiment

To prevent or break a stalemate in decision making, experimenting can be helpful. Experimentation starts thinking creatively (allowing people to think), trialing options, reflecting on them, and re-design. An approach that entails ‘trial and error’ can be promising when a situation is complex. In situations of complexity, important stakeholders can behave in a risk-averse way. Consequently, decision making for future developments can be postponed or obstructed. Instead of talking about an issue at length, experimentation can demonstrate how the system responds to interventions and what the consequences might be. Policy makers can learn from these experiments. It allows them to stimulate developments that are working, but also to adjust and reorient when things are not working out as expected. In addition, demonstrating how interventions work out will build trust among stakeholders and support for activities that, for example, recognize synergetic interactions between tourism and landscape.