Agroforestry as Policy Option for Forest-Zone Oil Palm Production in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The history of forest legality and oil palm expansion in Indonesia as context for current forest-related issues of local land use versus designation of the land as part of the forest zone;

- Spatial analysis of FZ-OP at the intersection of forests and tree crops for Indonesia as a whole and zoomed in on two provinces with higher-resolution data;

- Social and economic concerns on oil palm expansion and the role of smallholders in FZ-OP;

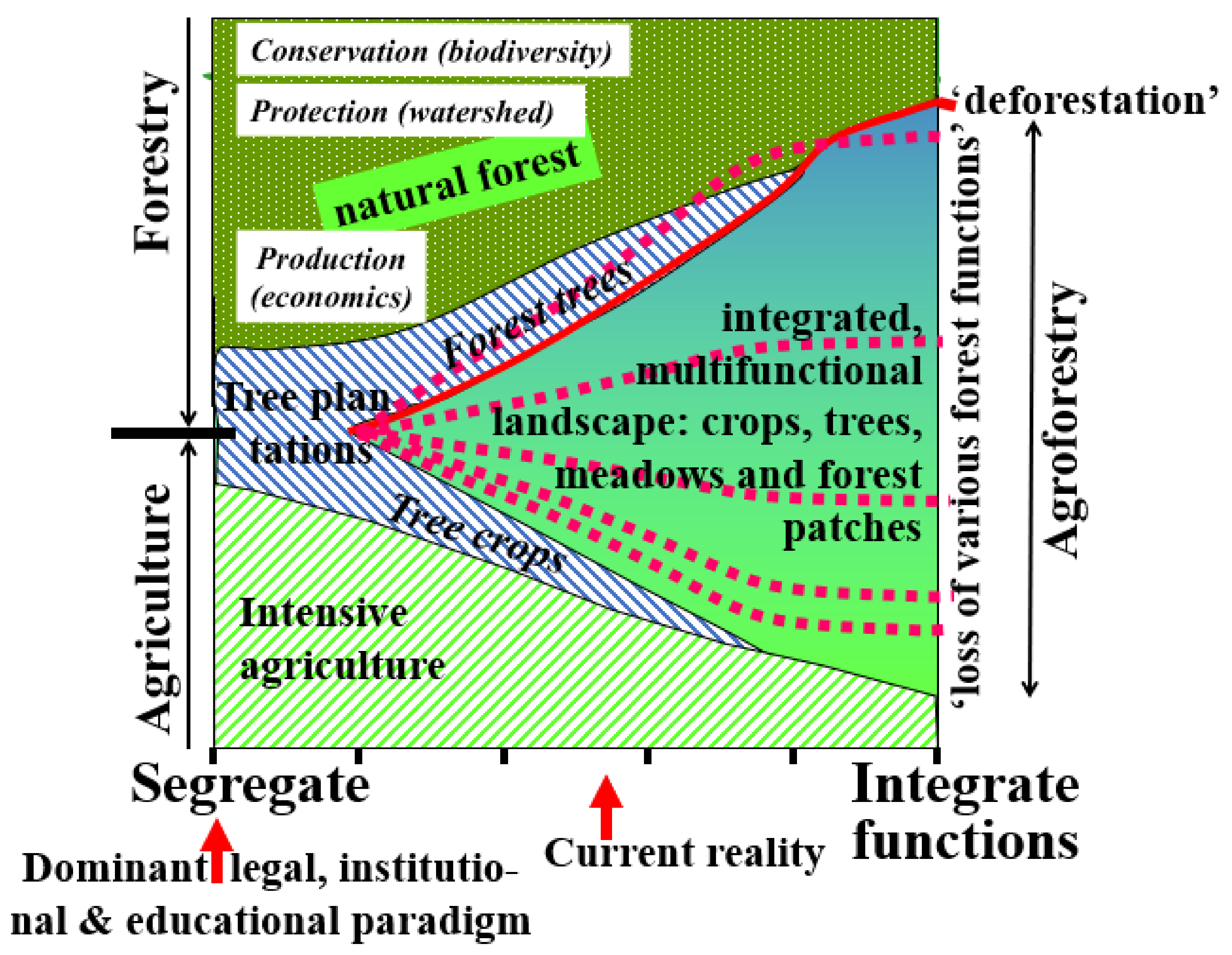

- Environmental concerns on tree crops in relation to the primary designated forest function in (A) production forest (income generation), (B) protection forest (watershed protection) and (C) Conservation areas (Biodiversity);

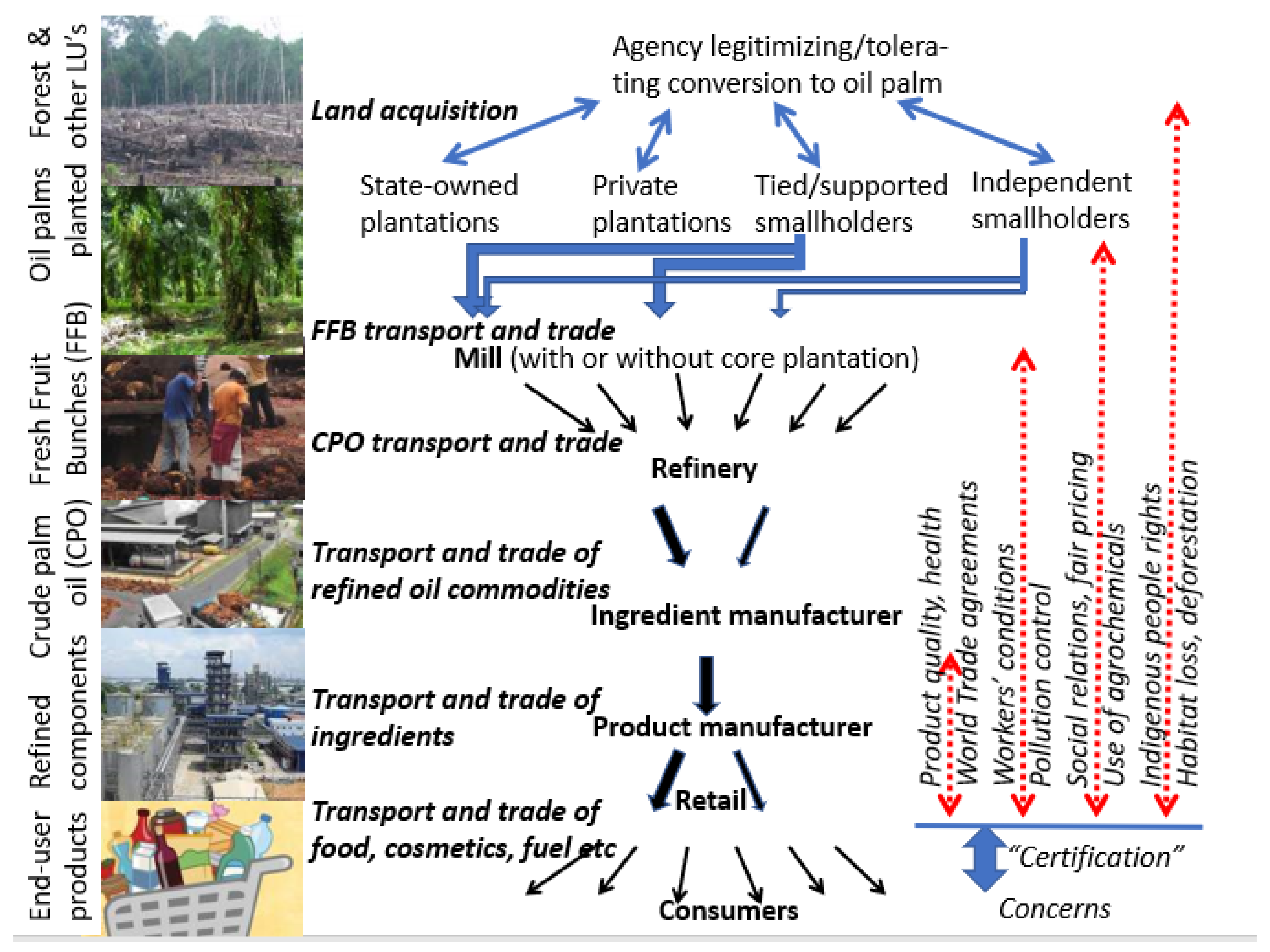

- Policy options linked to forest-related contexts, informed by the responses of various stakeholders along the palm-oil value chain to FZ-OP.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Maps

2.3. Public Consultation

3. Indonesian Context

3.1. Forest Legality

3.2. Complexity of Frontier Situation

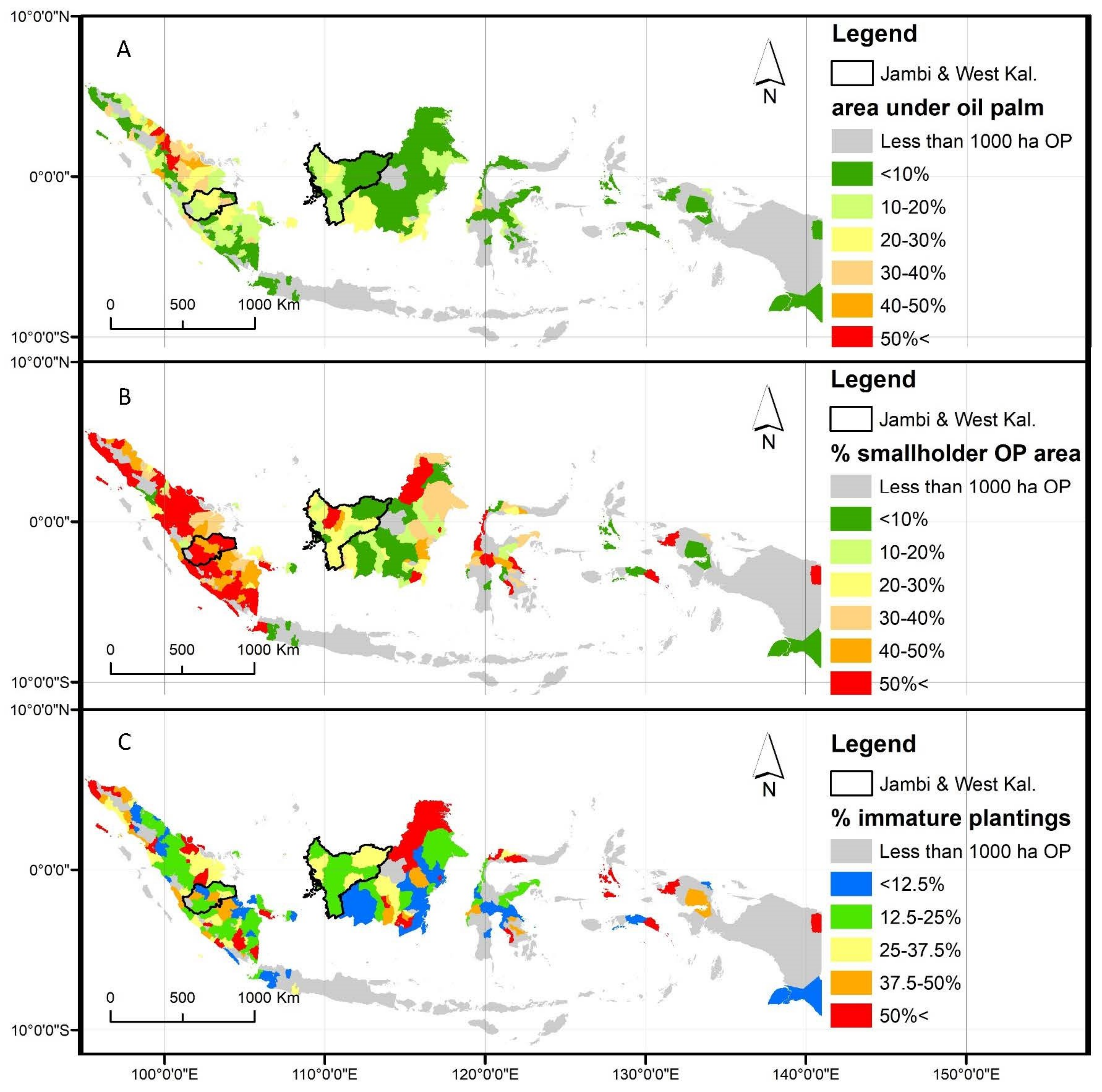

3.3. Total Oil Palm Area

4. Oil Palm in the Forest Zones of West Kalimantan and Jambi

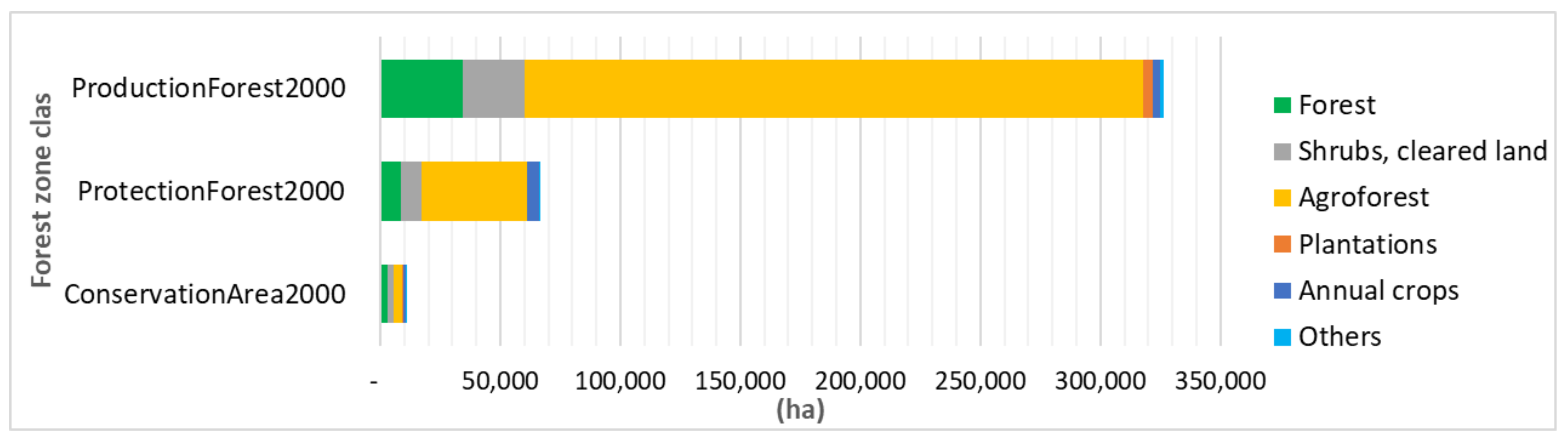

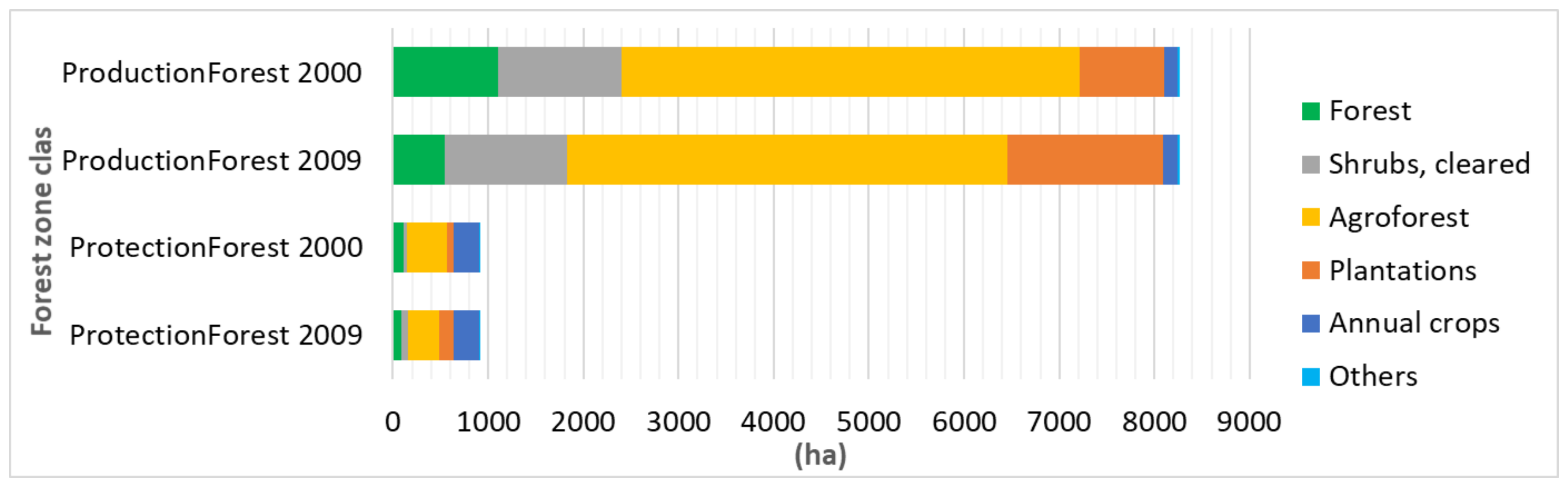

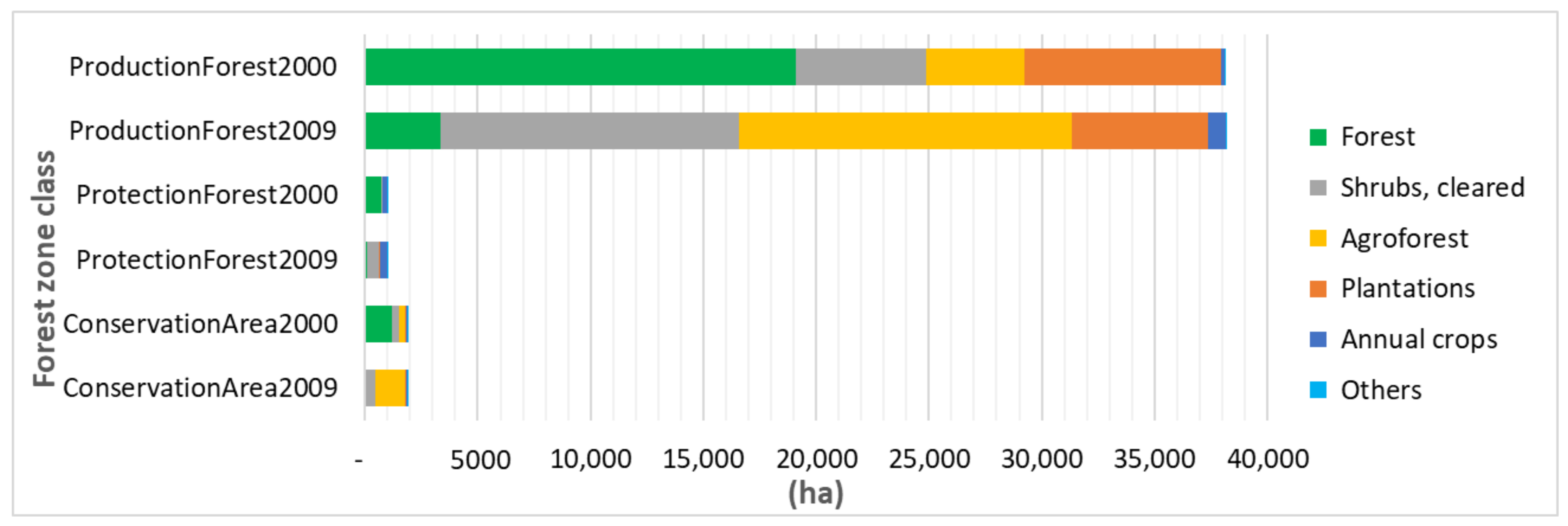

4.1. Data by Province and Forest Category

4.2. Data by Time Period—Land Cover Changes Involving Agroforest and Smallholder Oil Palm

5. Social Dimensions

5.1. Overview Indonesian Oil Palm Sector

5.2. Heterogeneity and Expansion amongst Oil Palm Smallholders

6. Ecological Dimensions

6.1. Biodiversity

6.2. Watershed Functions

6.3. Greenhouse Gas Emissions

7. Policy Responses and Options

7.1. FZ-OP as a Policy Issue

7.2. Institutional Responses

7.2.1. RSPO—Market Segmentation (‘Shifting Blame’)

7.2.2. ISPO—National Sovereignty

7.2.3. Deregulation and Crisis Responses

7.3. Current Policy Options Based on Land and Water Management

7.3.1. Legalize by Including Oil Palm in Forest Definition

7.3.2. Grandfathering

7.3.3. Evict Farmers, Destroy the Crops

7.3.4. Charge Land-Owner Benefit Shares to Pay for Forest Management Elsewhere

7.3.5. Agroforestry Concession

7.3.6. Swaps with High-Value Legal Deforestation Locations

7.3.7. Rewet Peatlands

7.4. Policy Options Based on Transport and Processing

7.4.1. Impose Legality Checks at the Mills

7.4.2. Apply a Transport Permit System

7.4.3. Segment Markets

7.5. Follow-Up Policy Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Details of the Initial Stakeholder Consultation

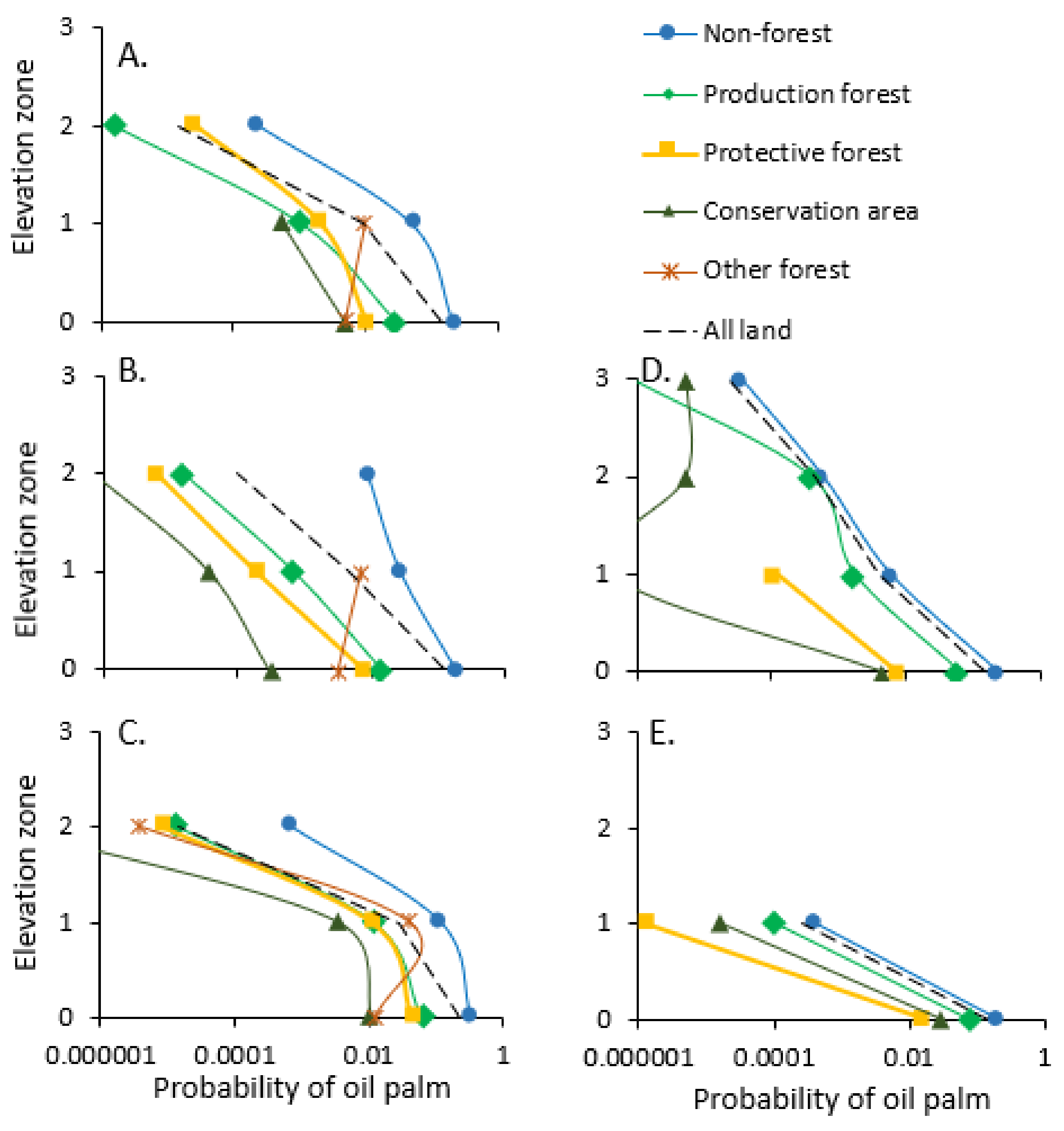

Appendix A.2. Analysis of FZ-OP by Elevation Zone and Forest Class

References

- Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.; Laestadius, L.; Bennett-Curry, A.; Buckingham, K.; Kumar, C.; Moll-Rocek, J.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Wilson, S.J. When is a forest a forest? Forest concepts and definitions in the era of forest and landscape restoration. Ambio 2016, 45, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noordwijk, M.; Minang, P.A. If We Cannot Define It, We Cannot Save It; ASB Policy Brief 15; ASB Partnership for the Tropical Forest Margins: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; p. 4. Available online:http://www.asb.cgiar.org/pdfwebdocs/ASBPB15.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- de Foresta, H.; Temu, A.; Boulanger, D.; Feuilly, H.; Gauthier, M. Towards the Assessment of Trees Outside Forests: A Thematic Report Prepared in the Framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk, M.; Suyamto, D.A.; Lusiana, B.; Ekadinata, A.; Hairiah, K. Facilitating agroforestation of landscapes for sustainable benefits: Tradeoffs between carbon stocks and local development benefits in Indonesia according to the FALLOW model. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 126, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijn, E.; Ainembabazi, J.H.; Wijaya, A.; Herold, M.; Angelsen, A.; Verchot, L.; Murdiyarso, D. Exploring different forest definitions and their impact on developing REDD+ reference emission levels: A case study for Indonesia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; FAO Forestry Paper No. 163; UN Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, R.J.; Reams, G.A.; Achard, F.; de Freitas, J.V.; Grainger, A.; Lindquist, E. Dynamics of global forest area: Results from the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, K.; Savenije, H. Oil Palm or Forests? More Than a Question of Definition; Policy Brief; Tropenbos International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk, M.; Dewi, S.; Minang, P.; Simons, T. 1.2 Deforestation-free claims: Scams or substance. In Zero Deforestation: A Commitment to Change; No. 58; Tropenbos International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, N.; Putz, F.E. Critical need for new definitions of “forest” and “forest degradation” in global climate change agreements. Conserv. Lett. 2009, 2, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, R.J.; Trabucco, A.; Verchot, L.V.; Muys, B. Land area eligible for afforestation and reforestation within the Clean Development Mechanism: A global analysis of the impact of forest definition. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2008, 13, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, C.; Michon, G. Redressing forestry hegemony when a forestry regulatory framework is best replaced by an agrarian one. For. Trees Livelihoods 2005, 15, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvianingsih, Y.A.; Hairiah, K.; Suprayogo, D.; van Noordwijk, M. Agroforests, swiddening and livelihoods between restored peat domes and river: Effects of the 2015 fire ban in Central Kalimantan (Indonesia). Int. For. Rev. 2020, 22, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiefnawati, R.; Villamor, G.B.; Zulfikar, F.; Budisetiawan, I.; Mulyoutami, E.; Ayat, A.; van Noordwijk, M. Stewardship agreement to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD): Case study from Lubuk Beringin’s Hutan Desa, Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. Int. For. Rev. 2010, 12, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, E.D.; Fairuzzana, S.; Willianto, D.; Pradesti, E.; McNamara, N.P.; Rowe, R.L.; van Noordwijk, M. Agroforestry Innovation through Planned Farmer Behavior: Trimming in Pine–Coffee Systems. Land 2020, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noordwijk, M.; Zomer, R.J.; Xu, J.; Bayala, J.; Dewi, S.; Miccolis, A.; Cornelius, J.P.; Robiglio, V.; Nayak, D.; Rizvi, J. Agroforestry options, issues and progress in pantropical contexts. In Sustainable Development through Trees on Farms: Agroforestry in Its Fifth Decade; Van Noordwijk, M., Ed.; World Agroforestry (ICRAF): Bogor, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Noordwijk, M.; Williams, S.; Verbist, B. Towards integrated natural resource management in forest margins of the humid tropics: Local action and global concerns. In ASB Lecture Notes; ICRAF: Bogor, Indonesia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomer, R.J.; Neufeldt, H.; Xu, J.C.; Ahrends, A.; Bossio, D.; Trabucco, A.; van Noordwijk, M.; Wang, M. Global tree cover and biomass carbon on agricultural land: The contribution of agroforestry to global and national carbon budgets. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Dargusch, P.; Harrison, S.; Herbohn, J. Why are there so few afforestation and reforestation Clean Development Mechanism projects? Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, E.; Schroeder, H. Governing and implementing REDD+. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minang, P.A.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Duguma, L.A.; Alemagi, D.; Do, T.H.; Bernard, F.; Agung, P.; Robiglio, V.; Catacutan, D.; Suyanto, S.; et al. REDD+ Readiness progress across countries: Time for reconsideration. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R.D.; Levy, S.; Carlson, K.M.; Gardner, T.A.; Godar, J.; Clapp, J.; Dauvergne, P.; Heilmayr, R.; de Waroux, Y.L.P.; Ayre, B.; et al. Criteria for effective zero-deforestation commitments. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheil, D.; Casson, A.; Meijaard, E.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Gaskell, J.; Sunderland-Groves, J.; Wertz, K.; Kanninen, M. The Impacts and Opportunities of Oil Palm in Southeast Asia: What do We Know and What Do We Need to Know; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.; Ghazoul, J.; Nelson, P.; Boedhihartono, A.K. Oil palm expansion transforms tropical landscapes and livelihoods. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noordwijk, M.; Pacheco, P.; Slingerland, M.; Dewi, S.; Khasanah, N. Palm Oil Expansion in Tropical Forest Margins or Sustainability of Production? Focal Issues of Regulations and Private Standards; World Agroforestry (ICRAF): Bogor, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmayr, R.; Carlson, K.M.; Benedict, J.J. Deforestation spillovers from oil palm sustainability certification. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 075002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condro, A.A.; Setiawan, Y.; Prasetyo, L.B.; Pramulya, R.; Siahaan, L. Retrieving the National Main Commodity Maps in Indonesia Based on High-Resolution Remotely Sensed Data Using Cloud Computing Platform. Land 2020, 9, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithöfer, D.; van Noordwijk, M.; Leimona, B.; Cerutti, P.O. Certify and shift blame, or resolve issues? Environmentally and socially responsible global trade and production of timber and tree crops. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Leimona, B.; van Noordwijk, M.; Mithöfer, D.; Cerutti, P.O. Certifying Environmental Social Responsibility. Environmentally and socially responsible global production and trade of timber and tree crop commodities: Certification as a transient issue-attention cycle response to ecological and social issues. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2018, 13, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- KLHK. Peta Penutupan Lahan Indonesia, 2000, 2010, 2018; Kementrian Lingkunan Hidup dan Kehutanan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018; Available online: http://geoportal.menlhk.go.id/arcgis/rest/services/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Pribadi, U.A.; Setiabudi Suryadi, I.; Laumonier, Y. West Kalimantan Ecological Vegetation Map 1:50000. 2020. Available online: https://data.cifor.org/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.17528/CIFOR/DATA.00203 (accessed on 15 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Descals, A.; Wich, S.; Meijaard, E.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Peedell, S.; Szantoi, Z. High-resolution global map of smallholder and industrial closed-canopy oil palm plantations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SK Menteri Kehutanan no 733/2014. Available online: https://fdokumen.com/document/sk-no733-tahun-2014-penunjukan-kalbar.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- SK Menteri Kehutanan no 863/2014. Available online: https://fdokumen.com/document/surat-keputusan-menteri-kehutanan-nomor-sk-863menhut-ii2014-tentang-kawasan.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Galudra, G.; Sirait, M. A discourse on Dutch colonial forest policy and science in Indonesia at the beginning of the 20th century. Int. For. Rev. 2009, 11, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, N.F.; Siscawati, M. Forestry Law, Masyarakat Adat and Struggles for Inclusive Citizenship in Indonesia. Routledge Handb. Asian Law 2016, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, L.; Moniaga, S. The space between: Land claims and the law in Indonesia. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 38, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hermosilla, A.C.; Fay, C. Strengthening Forest Management in Indonesia through Land Tenure Reform: Issues and Framework for Action; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The State of Indonesia’s Forest; Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Suwarno, A.; van Noordwijk, M.; Weikard, H.P.; Suyamto, D. Indonesia’s forest conversion moratorium assessed with an agent-based model of Land-Use Change and Ecosystem Services (LUCES). Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2018, 23, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directorate of Peat Degradation Control. Penetapan Fungsi Ekosistem Gambut (Peatland Ecosystem Function Establishment). 2020. Available online: http://pkgppkl.menlhk.go.id/v0/penetapan-fungsi-ekosistem-gambut/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Decree of Minister of Forestry No. 47/Kpts-II/1998 Concerning the Designation of +/− 29,000 Hectares of the Protective Forest and Limited Production Forest Zone, From the Pesisir Forest Grouping, in West Lampung District, Province of Lampung, Which Are Covered by Damar Agroforests (‘Repong Damar’) Managed by Communities under Customary Law (Masyarakat Hukum Adat), as a Zone with Distinct Purpose (Kawasan Dengan Tujuan Istimewa). Available online: https://peraturan.huma.or.id/pub/surat-keputusan-menteri-kehutanan-nomor-47-kpts-ii-1998 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Kusters, K.; De Foresta, H.; Ekadinata, A.; van Noordwijk, M. Towards solutions for state vs. local community conflicts over forestland: The impact of formal recognition of user rights in Krui, Sumatra, Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2007, 35, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, G. Domesticating Forests—How Farmers Manage Forest Resources; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Royer, S.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Roshetko, J.M. Does community-based forest management in Indonesia devolve social justice or social costs? Int. For. Rev. 2018, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakatama, A.; Pandit, R. Reviewing social forestry schemes in Indonesia: Opportunities and challenges. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.B.; Peluso, N.L. Frontiers of commodification: State lands and their formalization. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.W. Addicted to Rent: Corporate and Spatial Distribution of Forest Resources in Indonesia: Implications for Forest Sustainability and Government Policy; Indonesia-UK Tropical Forest Management Programme, Provincial Forest Management Programme: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Resosudarmo, B.P. (Ed.) The Politics and Economics of Indonesia’s Natural Resources; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Leitmann, J.; Boccucci, M.; Jurgens, E. Sustaining Economic Growth, Rural Livelihoods, and Environmental Benefits: Strategic Options for Forest Assistance in Indonesia; Worldbank: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2006; Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/986501468049447840/pdf/392450REVISED0IDWBForestOptions.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Mulyani, M.; Jepson, P. REDD+ and forest governance in Indonesia: A multistakeholder study of perceived challenges and opportunities. J. Environ. Dev. 2013, 22, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noordwijk, M.; Agus, F.; Dewi, S.; Purnomo, H. Reducing emissions from land use in Indonesia: Motivation, policy instruments and expected funding streams. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2014, 19, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, B.; Giessen, L. Towards a donut regime? Domestic actors, climatization, and the hollowing-out of the international forests regime in the Anthropocene. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 79, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Land grabs, land control, and Southeast Asian crop booms. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouyon, A.; De Foresta, H.; Levang, P. Does ‘jungle rubber’ deserve its name? An analysis of rubber agroforestry systems in southeast Sumatra. Agrofor. Syst. 1993, 22, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbist, B.; Putra, A.E.D.; Budidarsono, S. Factors driving land use change: Effects on watershed functions in a coffee agroforestry system in Lampung, Sumatra. Agric. Syst. 2005, 85, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, F.; Ehret, P. Smallholder cocoa in Indonesia: Why a cocoa boom in Sulawesi? In Cocoa Pioneer Fronts Since 1800; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1996; pp. 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest Management. Econ. Soc. 2007, 36, 264–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galudra, G.; van Noordwijk, M.; Agung, P.; Suyanto, S.; Pradhan, U. Migrants, land markets and carbon emissions in Jambi, Indonesia: Land tenure change and the prospect of emission reduction. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2014, 19, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pelzer, K.J. Pioneer Settlement in the Asiatic Tropics, Studies in land utilisation and agricultural colonization in southeastern Asia. In Pioneer Settlement in the Asiatic Tropics. Special Publication No. 29; American Geographical Society: New York, NY, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck, R.; McTaggart, W.D. Land settlement processes in Southeast Asia: Historical foundations, discontinuities, and problems. Asian Res. Serv. 1987, 15, 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen, A. Forest Cover Change in Space and Time: Combining the von Thunen and Forest Transition Theories; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck, R. The challenges of the agrarian transition in Southeast Asia. Labour Cap. Soc. 2004, 37, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dove, M. The Banana Tree at the Gate: A History of Marginal Peoples and Global Markets in Borneo; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia; Univ. of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk, M.; Bizard, V.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Tata, H.L.; Villamor, G.B.; Leimona, B. Tree cover transitions and food security in Southeast Asia. Glob. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L. How can the people’s sovereignty be achieved in the oil palm sector? Is the plantation model shifting in favour of smallholders. In Land and Development in Indonesia: Searching for the People’s Sovereignty; McCarthy, J.F., Robinson, K., Eds.; ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute: Singapore, 2016; pp. 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- Colfer, C.J.P.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P. Which way forward. In People, Forests and Policymaking in Indonesia; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, M.; Olsson, P.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Exploring the role of local ecological knowledge in ecosystem management: Three case studies. In Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folkes, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamor, G.B.; Pontius, R.G.; van Noordwijk, M. Agroforest’s growing role in reducing carbon losses from Jambi (Sumatra), Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 14, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Wilson, K.A.; Budiharta, S.; Kusworo, A.; Meijaard, E.; Law, E.A.; Friedman, R.; Hutabarat, J.A.; Indrawan, T.P.; St John, F.A.; et al. Heterogeneous impacts of community forestry on forest conservation and poverty alleviation: Evidence from Indonesia. People Nat. 2019, 1, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Estate Crops. Tree Crop Estate Statistics of Indonesia 2018–2020—Palm Oil; Directorate General of Estate, Ministry of Agriculture: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiar, I.; Suradiredja, D.; Santoso, H.; Saputra, W. Hutan Kita Bersawit–Gagasan Penyelesaian untuk Perkebunan Kelpa Sawit dalam Kawasan Hutan; KEHATI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gaveau, D.; Sheil, D.; Husnayaen Salim, M.A.; Arjakusuma, S.; Ancrenaz, M.; Pacheco, P.; Meijaard, E. Rapid conversions and avoided deforestation: Examining four decades of industrial plantation expansion in Borneo. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Sheil, D.; Wich, S.A.; Carlson, K.M.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Brooks, T.M. (Eds.) Oil Palm and Biodiversity. A Situation Analysis by the IUCN Oil Palm Task Force; IUCN Oil Palm Task Force: Gland, Switzerland, 2018; p. 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, K.G.; Mosnier, A.; Pirker, J.; McCallum, I.; Fritz, S.; Kasibhatla, P.S. Shifting patterns of oil palm driven deforestation in Indonesia and implications for zero-deforestation commitments. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJP. Statistik Perkebunan Indonesia; Kelapa Sawit 2018–2020; Direktorat Jenderal Perkebunan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Sistem Informasi Administrasi Kependudukan, Kemendagri, 2019. Indonesia Administrative Level 0–4 Boundaries, Indonesia (IDN) Administrative Boundary Common Operational Database (COD-AB), Update 23 December 2019, Badan Pusat Statistik, Sistem Informasi Administrasi Kependudukan. Kemendagri (Ministry of Home Affairs). Available online: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/indonesia-administrative-level-0-4-boundariesx (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Potter, L. Where Are the Swidden Fallows Now? An Overview of Oil Palm and Dayak Agriculture across Kalimantan, with Case Studies from Sanggau, in West Kalimantan. In Shifting Cultivation and Environmental Change: Indigenous People, Agriculture and Forest Conservation; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Penot, E.; Chambon, B.; Wibawa, G. History of rubber agroforestry systems development in Indonesia and Thailand as alternatives for sustainable agriculture and income stability. Int. Proc. IRC 2017, 1, 497–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feintrenie, L.; Levang, P. Sumatra’s rubber agroforests: Advent, rise and fall of a sustainable cropping system. Small-Scale For. 2009, 8, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therville, C.; Feintrenie, L.; Levang, P. Farmers’ perspectives about agroforests conversion to plantations in Sumatra. Lessons learnt from Bungo District (Jambi, Indonesia). For. Trees Livelihoods 2011, 20, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, L.P.; Miettinen, J.; Liew, S.C.; Ghazoul, J. Remotely sensed evidence of tropical peatland conversion to oil palm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5127–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyanti, D.; Hein, L.; Kroeze, C.; Zuhdi, M.; Saad, A. Scenarios for withdrawal of oil palm plantations from peatlands in Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Forest Watch. Universal Mill List. 2020. Available online: http://data.globalforestwatch.org/datasets/universal-mill-list/data (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- ten Kate, A.; Kuepper, B.; Piotrowski, M. NDPE Policies Cover 83% of Palm Oil Refineries; Implementation at 78%. Available online: https://chainreactionresearch.com/report/ndpe-policies-cover-83-of-palm-oil-refineries-implementation-at-75/ (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Budidarsono, S.; Susanti, A.; Zoomers, A. Oil palm plantations in Indonesia: The implications for migration, settlement/resettlement and local economic development. In Biofuels—Economy, Environment and Sustainability; INTECH: London, UK, 2013; pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJP. Statistik Perkebunan Indonesia; Kelapa Sawit; Direktorat Jenderal Perkebunan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jelsma, I.; Schoneveld, G.C.; Zoomers, A.; van Westen, A.C.M. Unpacking Indonesia’s independent oil palm smallholders: An actor-disaggregated approach to identifying environmental and social performance challenges. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoneveld, G.C.; van der Haar, S.; Ekowati, D.; Andrianto, A.; Komarudin, H.; Okarda, B.; Jelsma, I.; Pacheco, P. Certification, good agricultural practice and smallholder heterogeneity: Differentiated pathways for resolving compliance gaps in the Indonesian oil palm sector. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, K.N.; Glasbergen, P.; Offermans, A. Sustainability Certification and Palm Oil Smallholders’ Livelihood: A comparison between scheme smallholders and independent smallholders in Indonesia. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euler, M.; Schwarze, S.; Siregar, H.; Qaim, M. Oil Palm Expansion among Smallholder Farmers in Sumatra, Indonesia. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 658–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFC. Diagnostic Study on Indonesian Palm Oil Smallholders: Developing a Better Understanding of Their Performane and Potential; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, P. How Does Legislation Affect Oil Palm Smallholders in the Sanggau District of Kalimantan, Indonesia? Australas. J. Nat. Resour. Law Policy 2011, 14, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Indonesia: Strategies for Sustained Development of Tree Crops. In Agriculture Operations Division; Asia Regional Office, Ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Badrun, M. Milestone of Change: Developing a Nation through Oil Palm “PIR”; Directorate General of Estate Crops: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011; p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Mongabay. Indonesia Moves to End Smallholder Guarantee Meant to Empower Palm Oil Farmers. 2020. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2020/05/indonesia-palm-oil-plasma-plantation-farmers-smallholders/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Jelsma, I.; Slingerland, M.; Giller, K.E.; Bijman, J. Collective action in a smallholder oil palm production system in Indonesia: The key to sustainable and inclusive smallholder palm oil? J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemeter. Overview of Indonesian Smallholder Farmers: A Typology of Organizational Models, Needs, and Investment Opportunities; Daemeter: Bogor, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cramb, R.A. Palmed Off: Incentive Problems with Joint-Venture Schemes for Oil Palm Development on Customary Land. World Dev. 2013, 43, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, A.; Maryudi, A. Development narratives, notions of forest crisis, and boom of oil palm plantations in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 73, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, J.-F.; De Koninck, R. The return of the plantation? Historical and contemporary trends in the relation between plantations and smallholdings in Southeast Asia. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, I.; Kubitza, C.; Krishna, V.V.; Corre, M.D.; Mußhoff, O.; Pütz, P.; Drescher, J.; Rembold, K.; Ariyanti, E.S.; Barnes, A.D.; et al. Trade-offs between multifunctionality and profit in tropical smallholder landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feintrenie, L.; Chong, W.; Levang, P. Why do Farmers Prefer Oil Palm? Lessons Learnt from Bungo District, Indonesia. Small-Scale For. 2010, 9, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitza, C.; Krishna, V.V.; Alamsyah, Z.; Qaim, M. The economics behind an ecological crisis: Livelihood effects of oil palm expansion in Sumatra, Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsma, I.; Woittiez, L.S.; Ollivier, J.; Dharmawan, A.H. Do wealthy farmers implement better agricultural practices? An assessment of implementation of Good Agricultural Practices among different types of independent oil palm smallholders in Riau, Indonesia. Agric. Syst. 2019, 170, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woittiez, L.S.; Slingerland, M.; Rafik, R.; Giller, K.E. Nutritional imbalance in smallholder oil palm plantations in Indonesia. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 111, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.F.; Zen, Z. Agribusiness, agrarian change, and the fate of oil palm smallholders in Jambi. In The Oil Palm Complex: Smallholders, Agribusiness and the State in Indonesia and Malaysia; Cramb, R., McCarthy, J.F., Eds.; NUS Press: Singapore, 2016; pp. 109–155. ISBN 978-981-4722-06-3. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, V.; Euler, M.; Siregar, H.; Qaim, M. Differential livelihood impacts of oil palm expansion in Indonesia. Agric. Econ. 2017, 48, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, V.V.; Kubitza, C.; Pascual, U.; Qaim, M. Land markets, Property rights, and Deforestation: Insights from Indonesia. World Dev. 2017, 99, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, H.; Shantiko, B.; Sitorus, S.; Gunawan, H.; Achdiawan, R.; Kartodihardjo, H.; Dewayani, A.A. Fire economy and actor network of forest and land fires in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 78, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen, Z.; Barlow, C.; Gondowarsito, R.; McCarthy, J.F. Interventions to promote smallholder oil palm and socio-economic improvement in Indonesia. In The Oil Palm Complex: Smallholders, Agribusiness and the State in Indonesia and Malaysia; Cramb, R., McCarthy, J.F., Eds.; NUS Press: Singapore, 2016; pp. 78–108. ISBN 978-981-4722-06-3. [Google Scholar]

- Aulia, A.; Sandhu, H.; Millington, A. Quantifying the Economic Value of Ecosystem Services in Oil Palm Dominated Landscapes in Riau Province in Sumatra, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayompe, L.M.; Schaafsma, M.; Egoh, B.N. Towards sustainable palm oil production: The positive and negative impacts on ecosystem services and human wellbeing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, G.; Meijide, A.; Huth, N.; Knohl, A.; Kosugi, Y.; Burlando, P.; Fatichi, S. Ecohydrological changes after tropical forest conversion to oil palm. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 064035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzherbert, E.B.; Struebig, M.J.; Morel, A.; Danielsen, F.; Brühl, C.A.; Donald, P.F.; Phalan, B. How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, L.P.; Wilcove, D.S. Is oil palm agriculture really destroying tropical biodiversity? Conserv. Lett. 2008, 1, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.L. The Relationship between Carbon Emissions, Land Use Change and the Oil Palm Industry within Southeast Asia. Master’s Thesis, University of San Fransisco, San Fransisco, CA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/562 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Comte, I.; Colin, F.; Whalen, J.; Olivier, G.; Caliman, J.-P. Agricultural practices in oil palm plantations and their impact on hydrological changes, nutrient fluxes and water quality in Indonesia. A review. Adv. Agron. 2012, 116, 71–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merten, J.; Röll, A.; Guillaume, T.; Meijide, A.; Tarigan, S.; Agusta, H.; Hölscher, D. Water scarcity and oil palm expansion: Social views and environmental processes. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidzinski, K.; Andriani, R.; Komarudin, H.; Andrianto, A. Environmental and Social Impacts of Oil Palm Plantations and their Implications for Biofuel Production in Indonesia. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dislich, C.; Keyel, A.C.; Salecker, J.; Kisel, Y.; Meyer, K.M.; Auliya, M.; Wiegand, K. A review of the ecosystem functions in oil palm plantations, using forests as a reference system. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2017, 92, 1539–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morana, L.S. Oil Palm Plantations: Threats and Opportunities for Tropical Ecosystems. Thematic Focus: Ecosystem Management and Resource Efficiency; United Nation environment Programme Global Environmental Alert Service (GEAS): Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Safitri, L.; Sastrohartono, H.; Purboseno, S.; Kautsar, V.; Saptomo, S.; Kurniawan, A. Water Footprint and Crop Water Usage of Oil Palm (Eleasis guineensis) in Central Kalimantan: Environmental Sustainability Indicators for Different Crop Age and Soil Conditions. Water 2018, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, M.; Jennings, S.; Schreiber, W.; Sheane, R.; Royston, S.; Fry, J.; McGill, J. Study on the Environmental Impact of Palm Oil Consumption and on Existing Sustainability Standards; (07.0201/2016/743217/ETU/ENV.F3); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/forests/pdf/palm_oil_study_kh0218208enn_new.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Azhar, B.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Wood, J.; Fischer, J.; Manning, A.; McElhinny, C.; Zakaria, M. The conservation value of oil palm plantation estates, smallholdings and logged peat swamp forest for birds. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 2306–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, C.; Paltseva, J.; Searle, S. Ecological Impacts of Palm Oil Expansion in Indonesia; White Paper; International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.; Lindenmayer, D. Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation: A synthesis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007, 16, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallmetzer, N.; Schulze, C.H. Impact of oil palm agriculture on understory amphibians and reptiles: A Mesoamerican perspective. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 4, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdiyarso, D.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Wasrin, U.R.; Tomich, T.P.; Gillison, A.N. Environmental benefits and sustainable land-use options in the Jambi transect, Sumatra. J. Veg. Sci. 2002, 13, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aratrakorn, S.; Thunhikorn, S. Changes in bird communities following conversion of lowland forest to oil palm and rubber plantations in Thailand. Bird Conserv. Int. 2006, 16, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, F.A.; Edwards, D.P.; Hamer, K.C.; Davies, R.G. Impacts of logging and conversion of rainforest to oil palm on the functional diversity of birds in Sundaland. IBIS 2013, 155, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopik, O.; Gray, C.L.; Grafe, T.U.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Fayle, T.M. From rainforest to oil palm plantations: Shifts in predator population and prey communities, but resistant interactions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2014, 2, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payán, E.; Boron, V. The Future of Wild Mammals in Oil Palm Landscapes in the Neotropics. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2019, 2, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, F.; Beukema, H.; Burgess, N.; Parish, F.; Brühl, C.; Donald, P.; Fitzherbert, E. Biofuel plantations on forested lands: Double jeopardy for biodiversity and climate. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2009, 6, 242014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, V.; Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Smith, S.J. The Impacts of Oil Palm on Recent Deforestation and Biodiversity Loss. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancrenaz, M.; Oram, F.; Ambu, L.; Lackman, I.; Ahmad, E.; Elahan, H.; Meijaard, E. Of Pongo, palms and perceptions: A multidisciplinary assessment of Bornean orang-utans Pongo pygmaeus in an oil palm context. Oryx 2014, 49, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraniuk, C. Orangutans Are Hanging on in the Same Palm Oil Plantations That Displace Them, Conservationists Still Need to Work to Minimize Conflict between the Endangered Apes and Humans. Sci. Am. 2020. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/orangutans-are-hanging-on-in-the-same-palm-oil-plantations-that-displace-them/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Jonas, H.; Abram, N.K.; Ancrenaz, M. Addressing the Impact of Large-Scale Oil Palm Plantations on Orangutan Conservation in Borneo: A Spatial, Legal and Political Economy Analysis; IIED: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nellemann, C.; Miles, L.; Kaltenborn, B.; Virtue, M.; Ahlenius, H. Last Stand of the Orang-Utan; A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment: Nairobi, Kenya, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swarna Nantha, H.; Tisdell, C. The orangutan–oil palm conflict: Economic constraints and opportunities for conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suba, R.B.; van de Ploeg, J.; Zelfde, M.; Lau, Y.W.; Wissingh, T.F.; Kustiawan, W.; de Iongh, H.H. Rapid expansion of oil palm is leading to human–elephant conflicts in North Kalimantan province of Indonesia. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 10, 1940082917703508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhada, S.N.; Salim, S.; Nobilly, F.; Lechner, A.M.; Azhar, B. Conversion of peat swamp forest to oil palm cultivation reduces the diversity and abundance of macrofungi. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, A.; Darras, K.; Jayanto, H.; Grass, I.; Kusrini, M.; Tscharntke, T. Amphibian and reptile communities of upland and riparian sites across Indonesian oil palm, rubber and forest. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, e00492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillison, A.N.; Bignell, D.E.; Brewer, K.R.; Fernandes, E.C.; Jones, D.T.; Sheil, D.; May, P.H.; Watt, A.D.; Constantino, R.; Couto, E.G.; et al. Plant functional types and traits as biodiversity indicators for tropical forests: Two biogeographically separated case studies including birds, mammals and termites. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 1909–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unjan, R.; Nissapa, A.; Phitthayaphinant, P. An Identification of Impacts of Area Expansion Policy of Oil Palm in Southern Thailand: A Case Study in Phatthalung and Nakhon Si Thammarat Provinces. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 91, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anamulai, S.; Sanusi, R.; Zubaid, A.; Lechner, A.M.; Ashton-Butt, A.; Azhar, B. Land use conversion from peat swamp forest to oil palm agriculture greatly modifies microclimate and soil conditions. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.K.; Jiwan, N.; Rompas, A.; Jenito, J.; Osbeck, M.; Tarigan, A. Towards ‘hybrid accountability’ in EU biofuels policy? Community grievances and competing water claims in the Central Kalimantan oil palm sector. Geoforum 2014, 54, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, D.; Juen, L.; Selfa, T.; Peredo, A.M.; Montag, L.F.d.A.; Sombra, D.; Santos, M.P.D. Understanding local perceptions of the impacts of large-scale oil palm plantations on ecosystem services in the Brazilian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 109, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, S.D. Land Cover Change and its Impact on Flooding Frequency of Batanghari Watershed, Jambi Province, Indonesia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 33, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Mayer, A.; Watkins, D.; Castillo, M.M. Hydrologic impacts and trade-offs associated with developing oil palm for bioenergy in Tabasco, Mexico. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 31, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röll, A.; Niu, F.; Meijide, A.; Hardanto, A.; Hendrayanto, H.; Knohl, A.; Hölscher, D. Transpiration in an oil palm landscape: Effects of palm age. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 5619–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M. The water relations and irrigation requirements of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis): A review. Exp. Agric. 2011, 47, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.Y.; Teh, C.B.S.; Ainuddin, A.N.; Philip, E. Simple net rainfall partitioning equations for nearly closed to fully closed canopy stands. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 2018, 41, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Farmanta, Y.; Dedi, S. Rainfall Interception by Palm Plant Canopy. 2016. Available online: http://repository.unib.ac.id/11344/1/046%20Yong%20F%20%26%20Dedi%20S.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Hardanto, A.; Röll, A.; Niu, F.; Meijide, A.; Hendrayanto; Hölscher, D. Oil Palm and Rubber Tree Water Use Patterns: Effects of Topography and Flooding. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnzeel, L.A. Hydrological functions of tropical forests: Not seeing the soil for the trees? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 185–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, S.; Stiegler, C.; Wiegand, K.; Knohl, A.; Murtilaksono, K. Relative contribution of evapotranspiration and soil compaction to the fluctuation of catchment discharge: Case study from a plantation landscape. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2020, 65, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarga, E.; Hein, L.; Hooijer, A.; Vernimmen, R. Hydrological and economic effects of oil palm cultivation in Indonesian peatlands. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellaiah, D.; Yule, C.M. Effect of riparian management on stream morphometry and water quality in oil palm plantations in Borneo. Limnologica 2018, 69, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juen, L.; Cunha, E.J.; Carvalho, F.G.; Ferreira, M.C.; Begot, T.O.; Andrade, A.L. Effects of oil palm plantations on the habitat structure and biota of streams in eastern Amazon. River Res. Appl. 2016, 32, 2081–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheaves, M.; Johnston, R.; Miller, K.; Nelson, P.N. Impact of oil palm development on the integrity of riparian vegetation of a tropical coastal landscape. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 262, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, N.F.; Muis, Z.A.; Hashim, H. An integrated carbon footprint accounting and sustainability index for palm oil mills. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Rumpang, E.; Kho, L.K.; McCalmont, J.; Teh, Y.A.; Gallego-Sala, A.; Hill, T.C. An assessment of oil palm plantation aboveground biomass stocks on tropical peat using destructive and non-destructive methods. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasanah, N.M.; van Noordwijk, M.; Ningsih, H. Aboveground carbon stocks in oil palm plantations and the threshold for carbon-neutral vegetation conversion on mineral soils. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2015, 1, 1119964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowska, M.M.; Leuschner, C.; Triadiati, T.; Meriem, S.; Hertel, D. Quantifying above- and belowground biomass carbon loss with forest conversion in tropical lowlands of Sumatra (Indonesia). Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 3620–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, R.R.M.; Lima, N. Climate change affecting oil palm agronomy, and oil palm cultivation increasing climate change, require amelioration. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanah, N.M.; van Noordwijk, M.; Ningsih, H.; Rahayu, S. Carbon neutral? No change in mineral soil carbon stock under oil palm plantations derived from forest or non-forest in Indonesia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 211, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noordwijk, M.; Khasanah, N.M.; Dewi, S. Can intensification reduce emission intensity of biofuel through optimized fertilizer use? Theory and the case of oil palm in Indonesia. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories: Wetlands. In Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Hiraishi, T., Krug, T., Tanabe, K., Srivastava, N., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Troxler, T.G., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khasanah, N.M.; van Noordwijk, M. Subsidence and carbon dioxide emissions in a smallholder peatland mosaic in Sumatra, Indonesia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2019, 24, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rival, A.; Montet, D.; Pioch, D. Certification, labelling and traceability of palm oil: Can we build confidence from trustworthy standards? OCL 2016, 23, D609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinhout, B.; van de Hombergh, H. Setting the Biodiversity Bar for Palm Oil Certification; Assessing the Rigor of Biodiversity and Assurance Requirements of Palm Oil Standards; IUCN: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pye, O. Commodifying sustainability: Development, nature and politics in the palm oil industry. World Dev. 2019, 121, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggs, C.; Kuepper, B.; Piotr, M. Spot Market Purchases Allow Deforestation-Linked Palm Oil to Enter NDPE Supply Chains. Chain Reaction Research. Available online: https://chainreactionresearch.com/report/spot-market-purchases-allow-deforestation-linked-palm-oil-to-enter-ndpe-supply-chains/ (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Santika, T.; Law, E.; Wilson, K.A.; John, F.A.S.; Carlson, K.; Gibbs, H.; Morgans, C.L.; Ancrenaz, M.; Meijaard, E. Impact of Palm Oil Sustainability Certification on Village Well-Being and Poverty in Indonesia. 2020. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/5qk67/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- RSPO. Impact Update 2019. In Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil; RSPO: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Astari, A.J.; Lovett, J.C. Does the rise of transnational governance ‘hollow-out’ the state? Discourse analysis of the mandatory Indonesian sustainable palm oil policy. World Dev. 2019, 117, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, G.; Bitzer, V. The emergence of Southern standards in agricultural value chains: A new trend in sustainability governance? Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, V.; Richards, C. Framing sustainability: Alternative standards schemes for sustainable palm oil and South-South trade. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, N.K.; Offermans, A.; Glasbergen, P. Sustainable palm oil as a public responsibility? On the governance capacity of Indonesian Standard for Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO). Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoem, T. A False Hope? In An Analysis of the Draft New Indonesia Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Regulation; EIA: London, UK, 2020; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Noordwijk, M.; Leimona, B.; Amaruzaman, S. Sumber Jaya from conflict to source of wealth in Indonesia: Reconciling coffee agroforestry and watershed functions. In Sustainable Development through Trees on Farms: Agroforestry in Its Fifth Decade; Van Noordwijk, M., Ed.; World Agroforestry (ICRAF): Bogor, Indonesia, 2019; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Erb, M.; Anggal, W. Conflict and the growth of democracy in Manggarai District. In Deepening Democracy in Indonesia.; Erb, M., Sulistiyanto, P., Eds.; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 2009; pp. 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, E.N.; Maryudi, A.; Purwanto, R.H.; Lele, G. Opposing interests in the legalization of non-procedural forest conversion to oil palm in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEMPO English. Held Captive at Rokan Hulu; Tempo English: Jakarta, Indoenisa, 2016; pp. 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gaveau, D.L.A.; Salim, M.A.; Hergoualc’h, K.; Locatelli, B.; Sloan, S.; Wooster, M.; Marlier, M.E.; Molidena, E.; Yaen, H.; DeFries, R.; et al. Major atmospheric emissions from peat fires in Southeast Asia during non-drought years: Evidence from the 2013 Sumatran fires. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryanata, K. Fruit trees under contract: Tenure and land use change in upland Java, Indonesia. World Dev. 1994, 22, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiglio, V.; Reyes, M. Restoration through formalization? Assessing the potential of Peru’s Agroforestry Concessions scheme to contribute to restoration in agricultural frontiers in the Amazon region. World Dev. Perspect. 2016, 3, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingerland, M.A.; Khasanah, N.M.; van Noordwijk, M.; Susanti, A.; Meilantina, M. Improving smallholder inclusivity through integrating oil palm with crops. In Exploring Inclusive Palm Oil Production; ETFRN and Tropenbos International: Wageningen, The Netherland, 2019; pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Khasanah, N.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Slingerland, M.; Sofiyudin, M.; Stomph, D.; Migeon, A.F.; Hairiah, K. Oil Palm Agroforestry Can Achieve Economic and Environmental Gains as Indicated by Multifunctional Land Equivalent Ratios. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 3, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woittiez, L.S.; van Wijk, M.T.; Slingerland, M.; van Noordwijk, M.; Giller, K.E. Yield gaps in oil palm: A quantitative review of contributing factors. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 83, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehati. Solusi Sawitt Salam Kawasn Hutan [Oilmpalm Solutins in the Forest Zone]. SymSPOSia, Episode 10; Kehati: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fsEfK5jsGU&feature=youtu.be (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Nurrochmat, D.R.; Boer, R.; Ardiansyah, M.; Immanuel, G.; Purwawangsa, H. Policy forum: Reconciling palm oil targets and reduced deforestation: Landswap and agrarian reform in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 119, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiyama, M.; Neufeldt, H.; Dobie, P.; Hagen, R.; Njenga, M.; Ndegwa, G.; Mowo, J.G.; Kisoyan, P.; Jamnadass, R. Opportunities and challenges of landscape approaches for sustainable charcoal production and use. In Climate-Smart Landscapes: Multifunctionality in Practice; World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Outer islands usually refer to islands beyond densely populated Java, Madura and Bali islands. |

| No | Map Title | Year (s) | Extracted Class (es) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peta Penutupan Lahan Indonesia (Indonesia Land Cover Map) | 2000, 2009, 2018 | Agroforest | [31] |

| 2 | Ecological Vegetation Map of West Kalimantan | 2019 | Agroforest Rubber plantations Oil palm plantations | [32] |

| 3 | Global map of smallholder and industrial closed canopy oil palm plantations | 2019 | Oil palm plantations Independent smallholder oil palm | [33] |

| 4 | National Main Commodity Maps in Indonesia | 2019 | Oil palm Rubber | [28] |

| 5 | Kawasan hutan Provinsi Kalimantan Barat (Forest-zone Lands of West Kalimantan Province) | 2014 | [34] | |

| 6 | Kawasan hutan Provinsi Jambi (Forest-zone Lands of Jambi Province) | 2014 | [35] |

| No | Oil Palm Hectarage | Year | Approach and Methods | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16,800,000 | 2015–2017 | Multi-data analyses | Including unplanted area for industrial oil palm within forest zone | [75] |

| 2 | 14,896,964 | 2019 | Automatic classification using multi-data in GEE | RS methods; Oil palm and other major commodities | [28] |

| 3 | 14,724,420 | 2019 | Using trade statistics and yield data as a basis | Official Oil Palm statistics; industrial (private and state) and smallholders | [74] |

| 4 | 11,530,000 | 2019 | Automatic classification of sentinel imageries with NN | RS methods; Differentiation of industrial and smallholders | [33] |

| 5 | 11,100,000 | 2015–2017 | Visual interpretation of Landsat imageries | Oil palm and deforestation | [78] |

| Agroforest and Major Tree Crops | Source | Production Forest (ha) | Protection Forest (ha) | Conservation Areas (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Kalimantan, total area | 4,444,111 | 2,295,424 | 1,423,567 | |

| Agroforest | [32] +# | 318,521 (7%) | 66,631 (3%) | 10,576 (1%) |

| [31] + | 1,676,606 (38%) | 363,714 (16%) | 35,053 (2%) | |

| Rubber plantations | [32] | 7889 * | 14 * | |

| [28] | 8157 * | 764 * | 264 * | |

| Oil palm plantations | [32] | 80,771 (2%) | 6663 * | 1852 * |

| [28] | 186,037 (4%) | 29,753 (1%) | 4610 * | |

| [33] | 29,382 * | 3017 * | 59 * | |

| Independent smallholder oil palm | [33] | 8267 * | 906 * | 53 * |

| Jambi, total area | 1,235,639 | 180,170 | 634,431 | |

| Agroforest | [31] +# | 231,112 (19%) | 12,463 (7%) | 35,594 (6%) |

| Rubber plantations | [28] | 735 * | ||

| Oil palm plantations | [28] | 99,848 (8%) | 2964 (2%) | 20,065 (3%) |

| [33] | 40,399 (3%) | 337 * | 902 * | |

| Independent smallholder oil palm | [33] | 38,164 (3%) | 1032 (1%) | 1915 * |

| Province | West Kalimantan | Jambi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Source | [75] | [33] | [28] | [33] | [28] |

| Non-forest land | 93.65 | 96.30 | 89.93 | 89.05 | 83.05 |

| Production forest | 5.70 | 3.30 | 8.44 | 10.40 | 13.78 |

| Protection forest | 0.47 | 0.34 | 1.35 | 0.18 | 0.41 |

| Conservation areas | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 2.77 |

| Policy Option | Applicability Domain | Expected Consequences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation Areas | Protection/Production Forest on Peat | Protection Forest on Mineral Soil | Production Forest on Mineral Soil | Social | Economic | Environmental | |

| Land-focused: | |||||||

| 1.Legalize | NA | NA | NA | NA | ++ | ++ | -- |

| 2. Grandfathering | NA | NA | A | A | + | + | +/- |

| 3. Evict | NA | NA | NA | NA | -- | - | +/- |

| 4. Charge | A | NA | A | A | +/- | +/- | +/- |

| 5. Agroforestry concessions | NA | A | A | A | + | +/- | +/- |

| 6. Focus on high-value locations | A | A | A | A | +/- | +/- | + |

| 7. Rewet peatlands | NA | A | NA | NA | +/- | +/- | + |

| Value-chain based: | |||||||

| 8. Mill certification | A | NA | A | A | - | - | +/- |

| 9.Transport permits | A | NA | A | A | - | - | +/- |

| 10.Segment markets | A | NA | A | A | - | +/- | +/- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purwanto, E.; Santoso, H.; Jelsma, I.; Widayati, A.; Nugroho, H.Y.S.H.; van Noordwijk, M. Agroforestry as Policy Option for Forest-Zone Oil Palm Production in Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120531

Purwanto E, Santoso H, Jelsma I, Widayati A, Nugroho HYSH, van Noordwijk M. Agroforestry as Policy Option for Forest-Zone Oil Palm Production in Indonesia. Land. 2020; 9(12):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120531

Chicago/Turabian StylePurwanto, Edi, Hery Santoso, Idsert Jelsma, Atiek Widayati, Hunggul Y. S. H. Nugroho, and Meine van Noordwijk. 2020. "Agroforestry as Policy Option for Forest-Zone Oil Palm Production in Indonesia" Land 9, no. 12: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120531

APA StylePurwanto, E., Santoso, H., Jelsma, I., Widayati, A., Nugroho, H. Y. S. H., & van Noordwijk, M. (2020). Agroforestry as Policy Option for Forest-Zone Oil Palm Production in Indonesia. Land, 9(12), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120531