1. Introduction

Food security as a crucial global challenge has received much attention over the past two decades from international bodies, particularly in relation to sub-Saharan Africa. The importance of food security is highlighted by its elevation from a target of one of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG 1c) to a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 2). Food security is a multi-faceted agenda with several dimensions. Achieving food security means tackling its four dimensions—food availability, food accessibility, food utilisation, and food stability [

1]. This study uses agricultural productivity, a component of food availability, as the primary motivator.

The link between food security and agricultural productivity on the one hand and, land and land administration on the other hand has been explored practically and theoretically. Theoretically, Bennet et al. [

2] shows land administration as one of the support systems that lead to increased food security, though it undermines it in some cases. Van der Molen [

3] concludes that provision of food security requires the growth of agricultural productivity. Statistically about 821 million people in the world (10.9% of the world population) are undernourished [

4]. This is more pronounced in the sub-Saharan African (SSA) region, with 22.7% of the population (224.3 million people) being undernourished [

5]. However, even though Africa is estimated to contain 60% of the world’s uncultivated land, it is estimated that 65% of Africa’s arable land is too damaged to sustain viable food production [

6]. This problem points to the need to effectively manage the remainder of the arable land. The institutional and technical approaches to increasing agricultural productivity include, but are not limited to land and water access, access to markets, land tenure security, better roads, mechanisation, and use of fertilizers. However, one factor that is found to impede these institutional and technical approaches to increase agricultural productivity, among others, is the fragmented structure of farms [

7,

8,

9]. In many cases land consolidation has been touted as an effective solution to land fragmentation [

10,

11,

12]. This study starts from the endpoint of several studies including Abubakari et al., Blarel et al., Makana, and Takane [

13,

14,

15,

16], which conclude that conventional approaches to land consolidation are not viable on customary lands. These studies however stopped short of identifying the factors needed to be considered in order to develop a land consolidation approach on customary lands. A deeper analysis of specific cases was deemed necessary. Land consolidation procedures can be generally grouped into three main stages—the administrative preparatory stage, inventory and planning (technical) preparation stage, and the implementation stage [

17,

18]. This study focuses on the inventory and planning stage, which involve the collection and/or updating of land tenure and spatial information, the valuation of the farms and ancillary lands, and the preparation of the land reallocation and other land consolidation works, as well as the appeals from stakeholders for the plans. This paper summarises and synthesises the results of a study into the development of a responsible approach to land consolidation on customary lands, using Ghana as a case. The following section provides a background to the problem and breaks down the research objectives for the various components of the research.

2. Land Fragmentation and Land Consolidation on Customary Lands—A Background

Land fragmentation is the dispersion of a single farm-holding into several distinct farmland parcels, as well as a discrepancy between land use and ownership [

19,

20,

21]. Land fragmentation can seriously obstruct agricultural development as it negatively affects mechanisation and reduces productivity. Two forms of land fragmentation are found to exist—physical and land tenure fragmentation. Physical fragmentation is the spatial dispersion of farm parcels over a large area of land (also known as scattering) and the division of farmland parcels into small near-unproductive parcels (sub-division) [

7,

11]. Land tenure fragmentation is a discrepancy between land use and ownership [

21]. Blarel et al. [

14] and Netting [

22] in studies focused on Ghana, Rwanda, and Switzerland however show that land fragmentation has some positive impacts on farm productivity. McPherson [

23] therefore groups the causes of land fragmentation into two causes—supply-side and demand-side. The supply-side causes suggest that land fragmentation is a result of external forces such as population growth and cultural systems which may result in partible inheritance and land scarcity, as seen in most of Western Europe [

8]; and a change in government policy that results in a breakdown of common or communal property systems, as in the cases of Central and Eastern Europe and Eastern Nigeria [

24,

25]. In general, supply-side causes of land fragmentation have largely resulted in negative social, economic, and environmental impacts and outcomes. However, demand-side causes result from farmers’ choices, due to the positive impacts and benefits they reap from land fragmentation [

26].

Land fragmentation has always been prevalent in the agricultural system of customary lands, however its articulation as a problem is a recent occurrence [

27,

28,

29]. Despite this, recent studies examining food productivity in customary lands rather focus on the mechanisation of farms and fertilizer use than dealing with land fragmentation [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Land fragmentation on customary lands has two key causes—the customary land tenure (a supply-side cause), and the agricultural system (a demand-side cause) [

35].

Customary land is defined in several ways depending on the origins. However, there are three fundamental elements. The first is that land is held on the basis of locally evolved native land tenure; secondly, the basis of the land holding includes group and individual rights, with the former superseding the latter; and thirdly, the mechanisms for obtaining, using, distributing and disseminating these rights arise from accepted practices based on the group’s customs and traditions [

36,

37,

38]. Customary lands may also be referred to as community lands, communal lands, indigenous lands, traditional lands, among others [

36,

39,

40,

41]. Customary land tenure reflects the socio-cultural and spiritual bonds among generations—the many who have passed on, the living few, and the countless generation yet unborn. The basic tenet of customary land administration is that the current generation is a mere caretaker of the land meant to protect it as the legacy of their ancestors and safeguard it for the future generation [

42].

The nature of customary land tenure systems, together with the changing agricultural system of customary lands, also presents another key cause of land fragmentation [

29,

40]. Shifting cultivation, the predominant agricultural system of customary lands, allows for the tilling of the farms one after the other, gradually causing land fragmentation. The fragmentation of parcels is not a problem when population and demand for food is low: The farmer is able to take advantage of the fragmented parcels to deal with seasonal labour bottlenecks [

43,

44]. However, the increase in demand for food in urban areas, in tandem with the supply of fertilizer, causes the adoption of more intensive agricultural systems such as the annual cultivation and the multiple cropping farming systems which require simultaneous cultivation of the farm parcels, intensive weeding and ploughing [

45,

46,

47]. Higher returns to labour offered by the industrial and service sectors, as against the farming sector, also substantially reduce the available pool of labour that can be hired, resulting in the farm labour being determined by the household size [

44]. The labour shortage necessitates the adoption of large farm machinery, to keep up with the increasing urban food demand, which is difficult with small, scattered farms. The simultaneous farming of the fragmented parcels, use of rudimentary farming equipment, and application of fertilizer, still results in a less optimum productivity than experienced with the shifting cultivation [

46,

48]. This makes it necessary to deal with the land fragmentation situation.

Land consolidation has been successfully used to curb land fragmentation and increase food productivity, and further develop rural areas in Europe and to some extent in Asia [

11,

49]. However, the majority of land consolidation attempts in customary lands in sub-Saharan Africa have either failed or broken down the customary land tenure in the areas [

16,

33,

50,

51]. Despite the un-supportive land tenure and agricultural systems, attempts were made at land consolidation, predicated on the assumption that land consolidation was needed as an approach to developing the agricultural sector [

15,

34,

52]. Makana [

15] notes that land consolidation yielded rather positive results on some customary lands results in terms of increase in food production, though the customary land tenure system in those areas broke as a result. The results advanced for the successes and the failures of these land consolidation schemes include the nature of the participation of the parties involved, and the failure to adapt the land consolidation scheme to the conditions of the customary lands [

51,

53]. Malawi and Kenya provide examples. In Malawi, in the 1940s, although the colonial government successfully consolidated 81,000 hectares of farmlands, complete with infrastructural improvements, the programme still failed because it was solely run by the colonial government, without local participation, after being prematurely rolled out without consideration for local factors and conditions [

33]. Kenya’s land consolidation, also started by the colonial government, led to the complete overhaul of the land tenure system, to do away with the customary land tenure and replace it with individual titles as a major objective. The colonial government saw the customary system as a militating factor against the benefits of land consolidation and a well-functioning land market [

50]. This notwithstanding, the land consolidation planning was participatory, with the plans being drawn by the government officials together with the clan elders. However, the last step of the plan was to grant individual titles, thus effectively ending the coverage of customary land in these areas. The most recent of the land consolidation activities in sub-Saharan Africa is from Rwanda, which undertook a new form of land use consolidation [

54,

55,

56]. With the prime objective of increasing agricultural production, the reasoning behind this is to be able to undertake a land consolidation programme that does not alter the land tenure relations [

57]. The success of the Rwandan Land Use Consolidation, and the failure of the land consolidation approaches in Malawi and Kenya, coupled with the general sentiment towards some requirements for consolidating lands across sub-Saharan Africa, shows the need to investigate the knowledge gap between the development of land consolidation and customary lands with consideration for the local societal context through using a responsible approach.

Responsible approaches and policies apply broadly to a paradigm shift from traditional, and general approaches and policies to solving problems, to more societally and contextually based approaches and policies. The term “responsible” was mostly used in government and public administration circles to describe the system of accountability. Land consolidation as a land development tool dwells within a broader context. The adoption of responsible approaches to land consolidation is needed to be able to align the land consolidation approaches to the conditions that exist on customary lands [

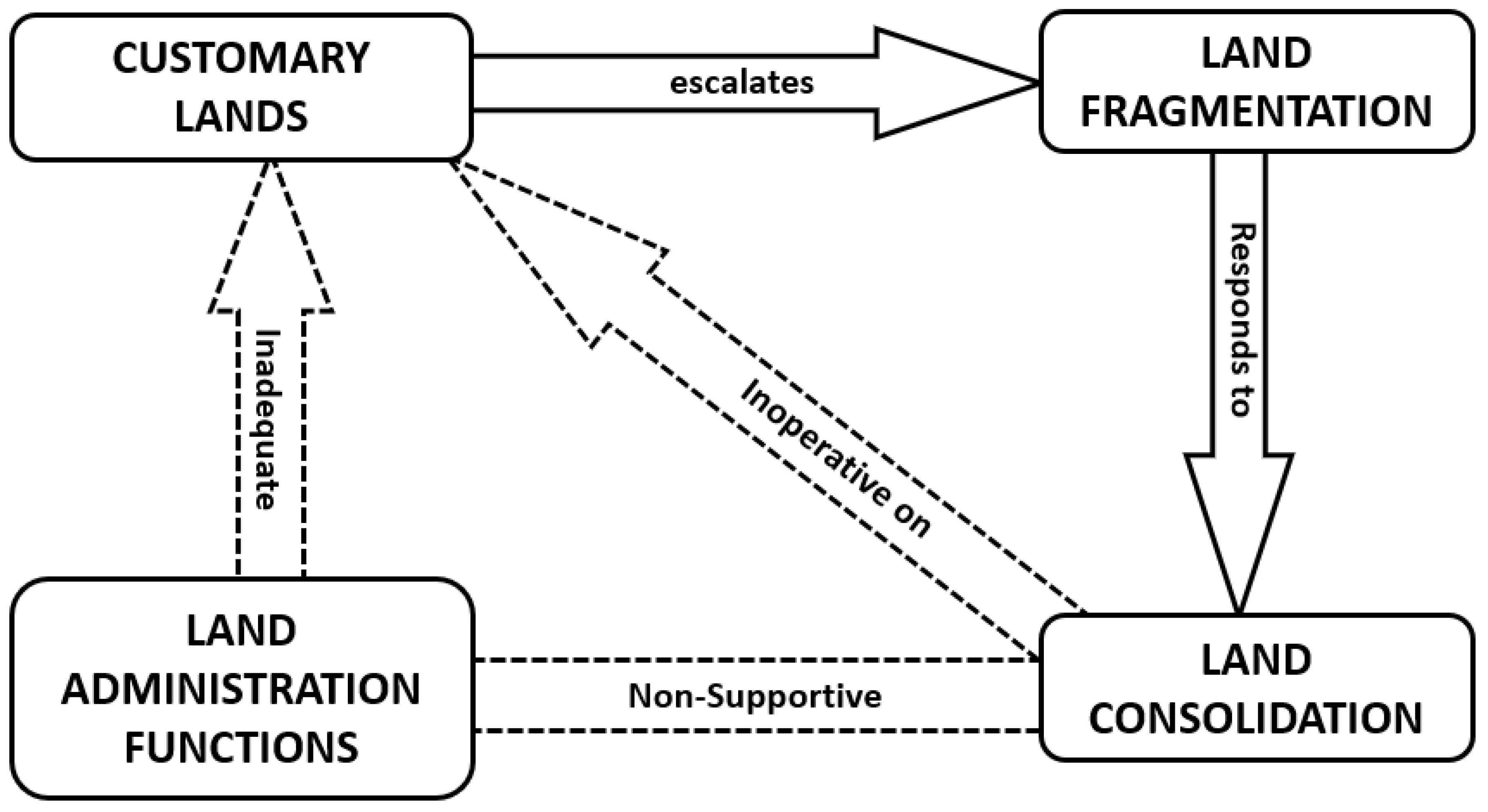

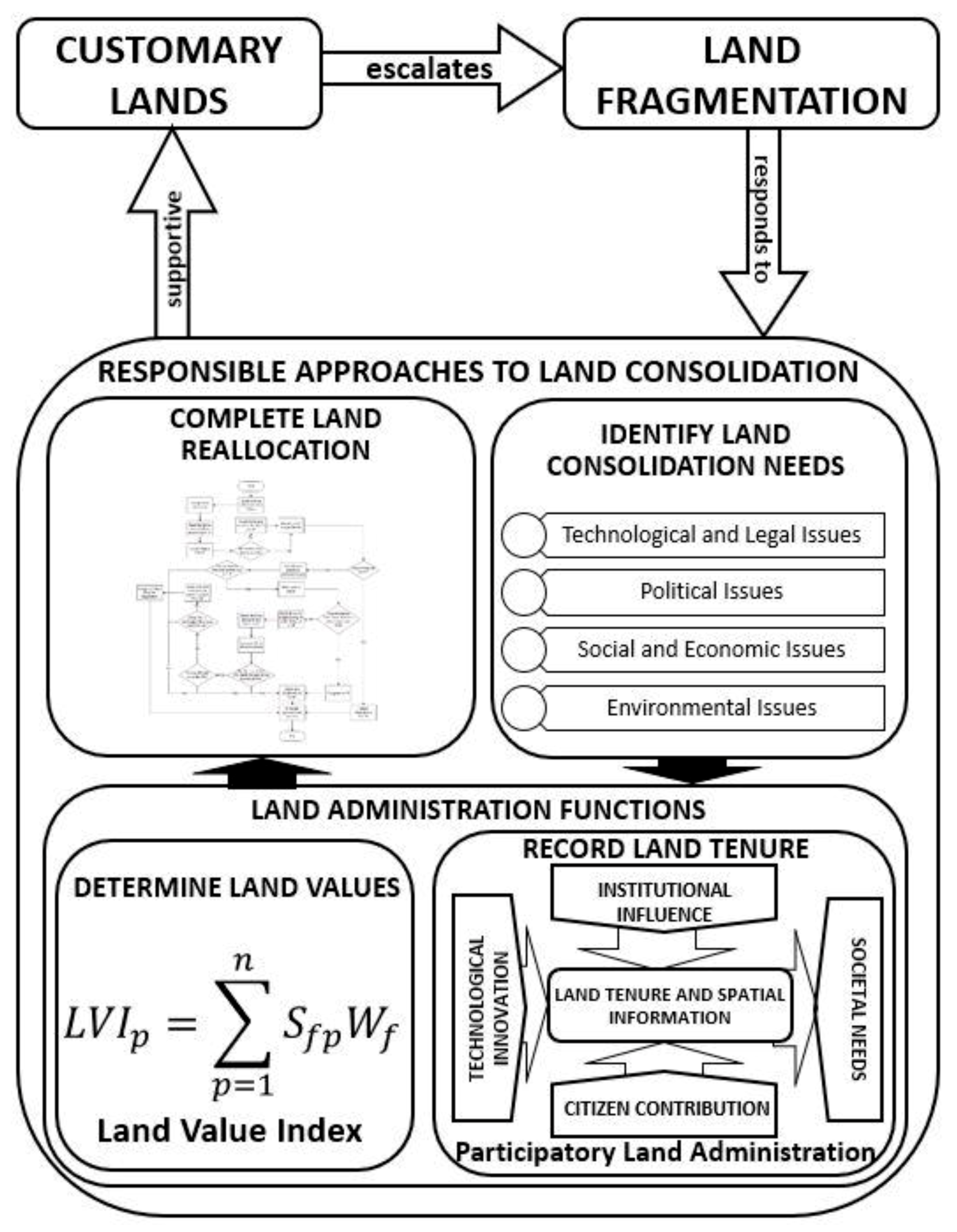

26]. There is therefore the need to comparatively study the areas that have already undertaken land consolidation on customary lands, to be able to identify their commonalities and peculiarities before a responsible land consolidation approach for customary lands can be developed. The technological advances in land administration that have paved the way for land administration to be aligned to customary lands and used as an aid to combat the problem of inadequate land information and the absence of land value. It is acknowledged that certain characteristics of customary lands cause land fragmentation and that land fragmentation can be reduced by land consolidation. However, attempts to undertake land consolidation on customary lands have largely failed in the face of inadequate land administration processes on customary lands. There is therefore the need to adapt responsible approaches to land consolidation. The concepts relating to the problems and associated in knowledge gaps in the development of a responsible land consolidation process are summarised in

Figure 1.

It is known that certain conditions on customary lands (land tenure and the farming system), escalate the occurrence of land fragmentation. It is also known that land fragmentation responds to land consolidation. However, it is seen that land consolidation has not been operative on customary lands. Therefore, to connect land consolidation with customary lands, it is necessary to improve the inadequate land administration functions on customary lands that cannot support land consolidation.

The development of a responsible approach on customary lands took four steps; first the factors that need to be addressed to develop a responsible land consolidation approach for customary lands were explored. An approach for collecting land information to support responsible land consolidation on customary lands was then developed and assessed. Furthermore, a land valuation approach to support responsible land consolidation on customary lands was also developed, and the above were applied to a process model for a land reallocation approach to support land consolidation on customary lands.

3. Methodology and Research Approach

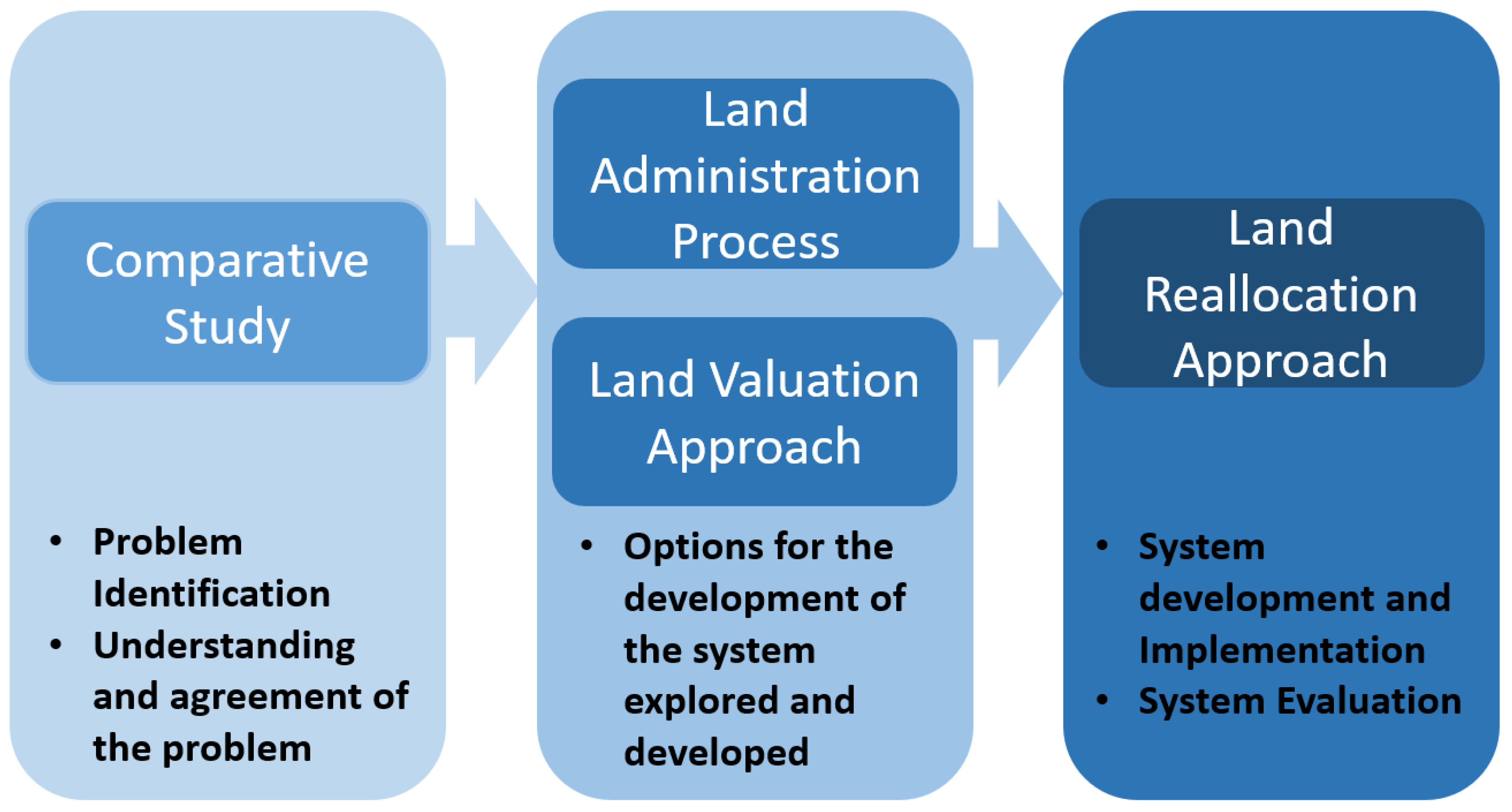

The choice of the research methodology is largely driven by the nature of the research problem, the objectives, as well as the questions asked to reach the objectives. When the research seeks a method that emphasizes the solving of problems through the combination of methods from different paradigms that allow for the generalizable and quantifiable results by answering questions related to how much? (qualitative methods), and those that allow for the rich and deep understanding of the situation, answering questions related to the who, what, and how (qualitative method) related to information systems, the design research is found to be most appropriate [

58]. Design research is preferable because it allows for the use of diverse research strategies needed when the research seeks to deal with real world complexities. The design research is operationalized in five steps. First step is the problem identification; second is understanding and agreement about the problem is generated; thirdly, the options for the development of the system is explored and the system is developed; fourth, the designed system is then implemented, and finally the implemented system is evaluated. The design research methodology is summarized in

Figure 2.

The first step requires the exploration of how land consolidation’s factors need to be addressed on customary lands, encompassing the first two steps of the design research. A comparative case study approach is adopted. In this vein, an analytical framework for understanding the reasons different land consolidation strategies are developed and adopted or adapted in different contexts, from existing literature, to form a scientific basis for the comparison. Using Van Dijk’s [

59] model of comparative analysis for cross-country exporting of knowledge, three countries with existing land consolidation strategies are selected, observed, and compared to Ghana’s rural customary lands. This model is grounded in the reasoning that in transferring development and planning approaches across international borders, it is necessary to understand how and why the approach was developed in the original context. The goal of using this model is to first understand the local contexts, and then to examine land consolidation factors and how they influenced the selection of the land consolidation strategy. The selected countries included the Netherlands, Lithuania, and Rwanda. Data from the Netherlands, Lithuania, Rwanda, and Ghana was collected through a document review—scientific literature, government policies, laws, and technical reports; and supplemented with interviews with land and agricultural sector officials, and farmers. In Ghana, further interviews were conducted with the traditional authorities and local government leaders.

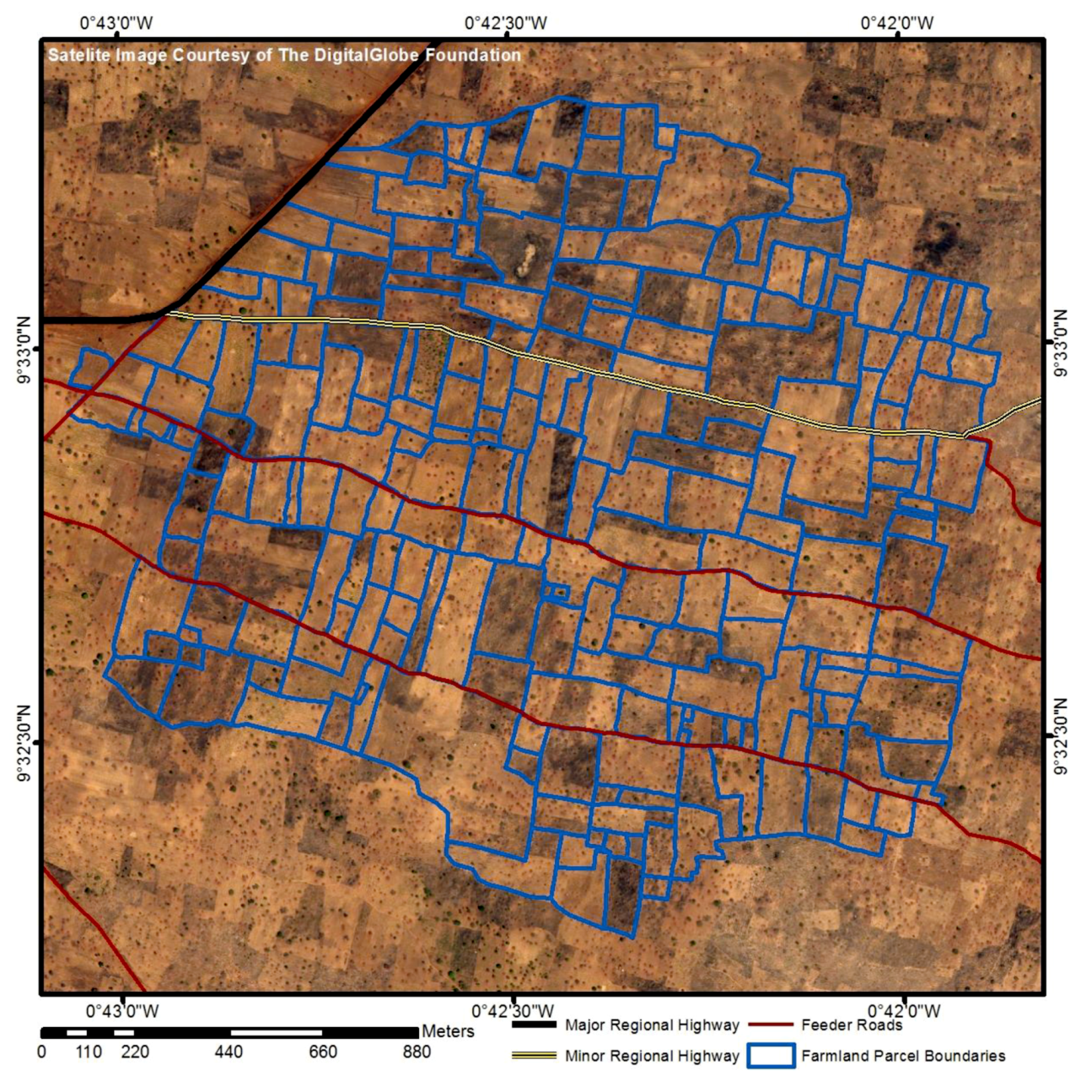

The second step used the experimental case study with a Living Lab approach. A Living Lab is based on two main concepts—first is the involvement of users early in the innovative process, and the second is experimentation in real-world settings, aimed at integrating the social structure and governance, as well as user participation in the innovative process [

60,

61,

62]. The stakeholders of the experiment were identified, and the process of mapping and recording the land rights was developed with the assistance of the Traditional Authority (the Nanton-Na and the family heads in the area), the leaders of the Farmers’ Association of the area and the Lands Commission. Two technologies were adopted for the experiment—a smartphone app and satellite imagery. The smartphone app used was Esri’s Collector for ArcGIS. The satellite image was a February 2016 GeoEye-1 satellite image of the area of interest was freely acquired from DigitalGlobe Foundation, and printed at a scale of 1:4000, which is within the range of scales recommended by Byamugisha et al. [

63] for mapping rural agricultural land parcels with medium density.

The third step developed a valuation approach for land consolidation. Here, the multiple attribute decision-making (MADM) method is used based on the general land valuation approach. MADM methods are flexible and can be adapted with ease to the development of indices being represented by a set of parameters, where the aim is to evaluate an object compared to a standard for which the application is concerned. In the case of this study, the standard is the most appropriate land parcel for farming. This approach is used because it is about to achieve quid pro quo values that can be used for land consolidation.

The fourth step is achieved using the process modelling method that details the steps of the approach taking into consideration the social, economic, cultural, technical, and political considerations on customary lands. The process model developed in this paper is a meso-micro-level procedural model. The meso-micro-level procedural model conveys best practices intended to guide real-world situations by providing prescriptive guidelines for a design and/or problem-solving activity with a focus on individual steps as well as end to end flows of the activity, where each step establishes objectives, and constraints for the next, with feedback loops between the steps for the possibility to re-work undesirable outcomes.

4. Overview of Study Area and a Background on Ghana’s Customary Lands

The study focuses on Ghana, an agriculturally dominant country. The choice of Ghana is made because it is one of the two countries that undertook efforts to adopt customary land tenure laws that were derived from an African angle, expend state influence out into the customary domain and strengthening the governance structures already in place right after independence [

64,

65]. The other country is Botswana. However, compared to Ghana, Botswana has a low land productivity that can still be improved and is one of Africa’s smallest agricultural economies [

66]. About 49% of the population of Ghana lives in rural areas, with 45% of the country’s labour population (15 years and above) being engaged in agriculture [

67]. Agriculture contributes to 54% of the Ghana’s gross domestic product, and accounts for over 40% of its export earnings, whilst at the same time providing over 90% of the food needs of the country. Out of the 258,539 km sq. area that Ghana covers, 57% is classified as agricultural land area.

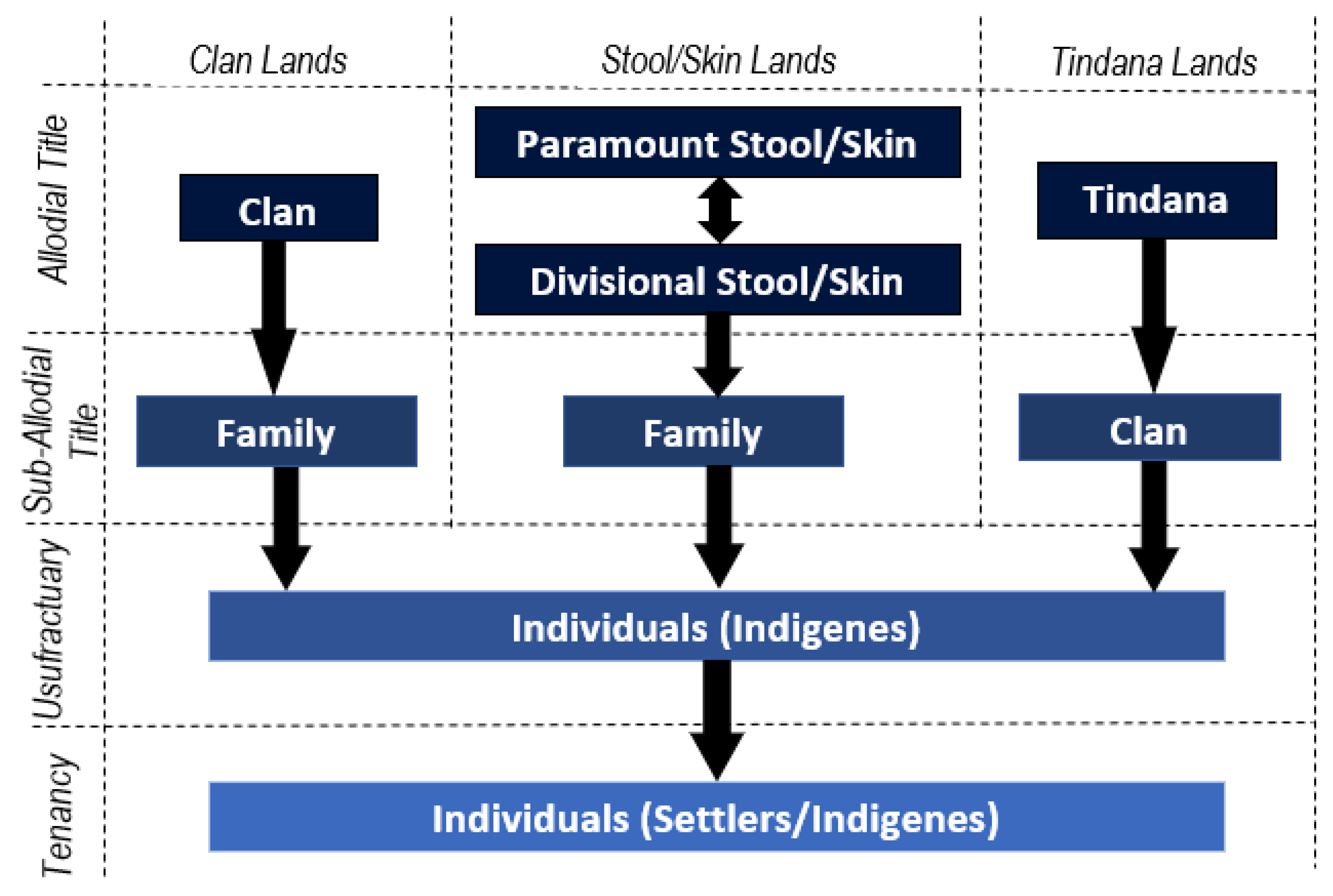

Customary lands are recognized by the 1992 Constitution of Ghana (Article 38) and cover 80% of the lands in Ghana with the remaining 20% being public lands vested in the President in trust for the people of Ghana [

68]. The main interests in customary land tenure that relate to farming are the Allodial Title, the Customary Law Freehold or Usufructuary interest, and Tenancy (

Figure 3) [

37,

69,

70]. The allodial title is held by the community and managed by its leaders under customary law, free from any restrictions and obligations, except such imposed by the laws of Ghana. The allodial interest cannot be transferred as this is restricted by the 1992 Constitution of Ghana and the customs, and it is exclusive to the community or tribe that holds the rights. The Usufructuary interest is exercised by individual members of a community to take possession of vacant land of which the community is the allodial owner subject to certain restrictions and obligations, upon payment of nominal consideration or free of charge [

42]. The Usufructuary interest is transferable within the allodial land owning group under certain strict circumstances. The Tenancy can be acquired by any person, indigene or otherwise, based on specific prior agreed terms, usually share cropping or an annual payment, usually for a term of one farming season. The tenant holds the land for the term exclusively, but subject to rules of the allodial title holder and/or the usufruct and cannot transfer his rights without the consent and concurrence of the landlord. Although the modes of acquiring the Usufructuary interest include the clearing of an unencumbered land followed by uninterrupted settlement, or as a gift or purchase; inheritance is currently the most common means of land acquisition [

37]. The Usufructuary interest is held in perpetuity except for situations of abandonment, forfeiture, or want of successor; in which case, the land reverts to the allodial title holder [

42,

71]. The nature of the Usufructuary interest restricts farmers from expanding, as contiguous parcels’ holders are unwilling to sell their parcels in order to hold the land for the future generations. This causes land fragmentation because to expand their operations, farmers move to parcels further away from their primary parcels.

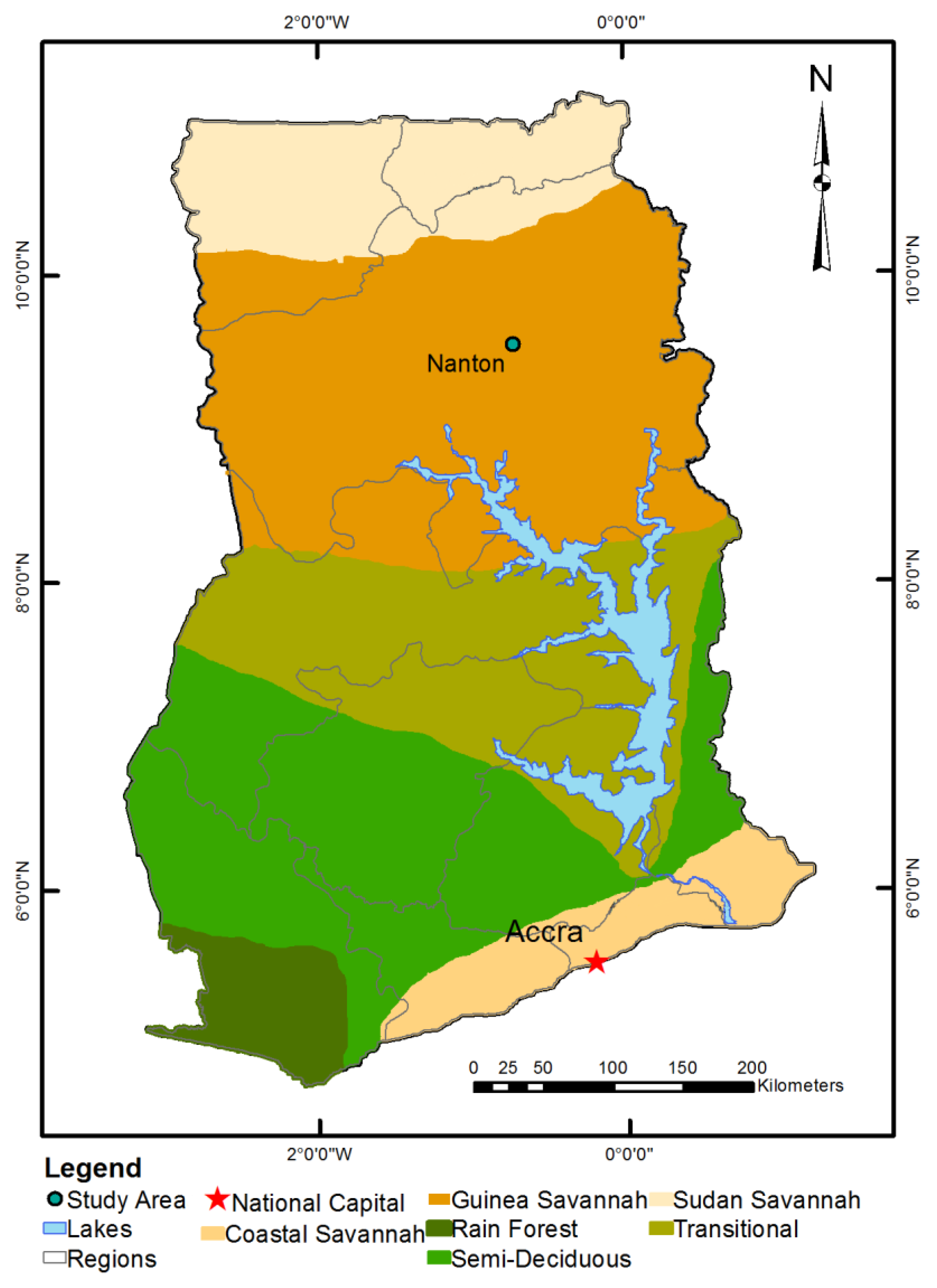

Farming in Ghana varies according to the seven agro-ecological zones—the rainforest, deciduous forest, semi-deciduous, transition, and the savannah zones (Guinea, Sudan, and Coastal) (

Figure 4). In the forest zones, plantation and tree crops such as cocoa, oil palm, coffee and rubber are pre-dominant. The savannah and transition zones are characterized mostly by annual crops such as maize, roots, sorghum, and cowpea. In terms of rain, the forest and coastal savannah areas have bimodal rainy season, giving rise to two farming seasons per year—a major and a minor farming season. In the Guinea and Sudan savannah, and transition zones, there is one rainy season.

This study is conducted in a farming community in one of the savannah zones of Ghana. These areas were chosen for two reasons. The first relates to the agro-ecological characteristics of the area. The savannah areas are characterized by tall grasses and a few trees (mostly shea, acacia, baobab, and mango) dotting the landscape. These conditions are favourable for the use of GNSS in this study, as the absence of tree cover will reduce the likelihood of multipath errors when using GNSS. The second reason relates to the tree crops grown. The growing of annual crops allows a certain amount of flexibility when dealing with the manipulation of farmland parcel arrangements. The area used for this study, Nanton is in the Guinea savannah agro-ecological zone, with the land tenure being held on the basis of the skin lands.

5. Outcomes of the Aspects of Responsible Land Consolidation

This section outlines the main results of the project, according to the research objectives. The results have been summarised in

Figure 5 with respect to the gaps in relationships between the concepts shown in

Section 2.

5.1. Factors that Influence the Selection and Development of a Responsible Land Consolidation Approach

To identify how local factors, affect the selection of a land consolidation approach, three countries with contemporary land consolidation approaches were identified—the Netherlands, Lithuania, and Rwanda. The Netherlands was found to have land consolidation approaches that have evolved over five centuries, from Voluntary Land Exchange, to Land consolidation by agreement and Land Development. Lithuania has developed the Voluntary and Simple Land Consolidation over the past fifteen years, and Rwanda developed its own form of land consolidation, the land use consolidation in 2008. A harmonisation of the land consolidation approaches in these three countries shows that generalising the development of land consolidation approaches in a continuum from simple and voluntary approaches to comprehensive and compulsory approaches, as is done in certain studies, based on the development level of the locality, does not result in development of a responsible land consolidation strategy, but the local needs and societal makeup is key in the selection of the land consolidation approach. The results showed five key areas around which the development of the land consolidation approaches centre—the government support for and role in land management activities; the land market and land mobility; land tenure, land fragmentation and farming technology; the coverage of a land information system, as well as environmental and ecological considerations.

Comparing these influences, it was found that the state of the economy, the type of land fragmentation, ecological considerations, and the level of farming technology in Ghana was similar to at least one of the countries with an existing land consolidation approach. The conditions that did not bear any similarities with existing land consolidation strategies were the low influence of the government in land management activities, the absence of a land market, the inadequate coverage of a supportive land information system, and the customary land tenure. However, it was found that the conditions that did not adequately match the countries with existing land consolidation approaches require a substantial change to the social, economic, and cultural structure of the communities, in order to align them with the existing approaches. These conditions therefore require innovative and responsible interventions to enable response to the requirements of land consolidation. The detailed results of this objective may be found in Asiama et al. [

35].

5.2. Participatory Land Administration: An Approach to Collecting Land Information

Land administration processes in Ghana have been found to be slow and expensive in relation to the urgency of the results, and out of reach of most of the citizens. Furthermore, they have failed to integrate all forms of land tenure arrangements especially secondary and customary land rights. It was found that the innovative approaches to land administration on customary lands in Ghana which include the systematic titling by the Millennium Development Authority, the Paralegal Titling Project and the Community-based Land Survey Tool, all had the same problem of being slow, expensive, and concentrated in urban areas and on large-scale farms. Here, participatory land administration (PLA) that sits at the nexus of the drivers of technological innovation and approaches to development studies; where traditional land administration approaches, deeply rooted in western views, together with bottom-up emerging approaches that challenge traditional approaches, as well as technological advances that drive these approaches together with the growing societal needs.

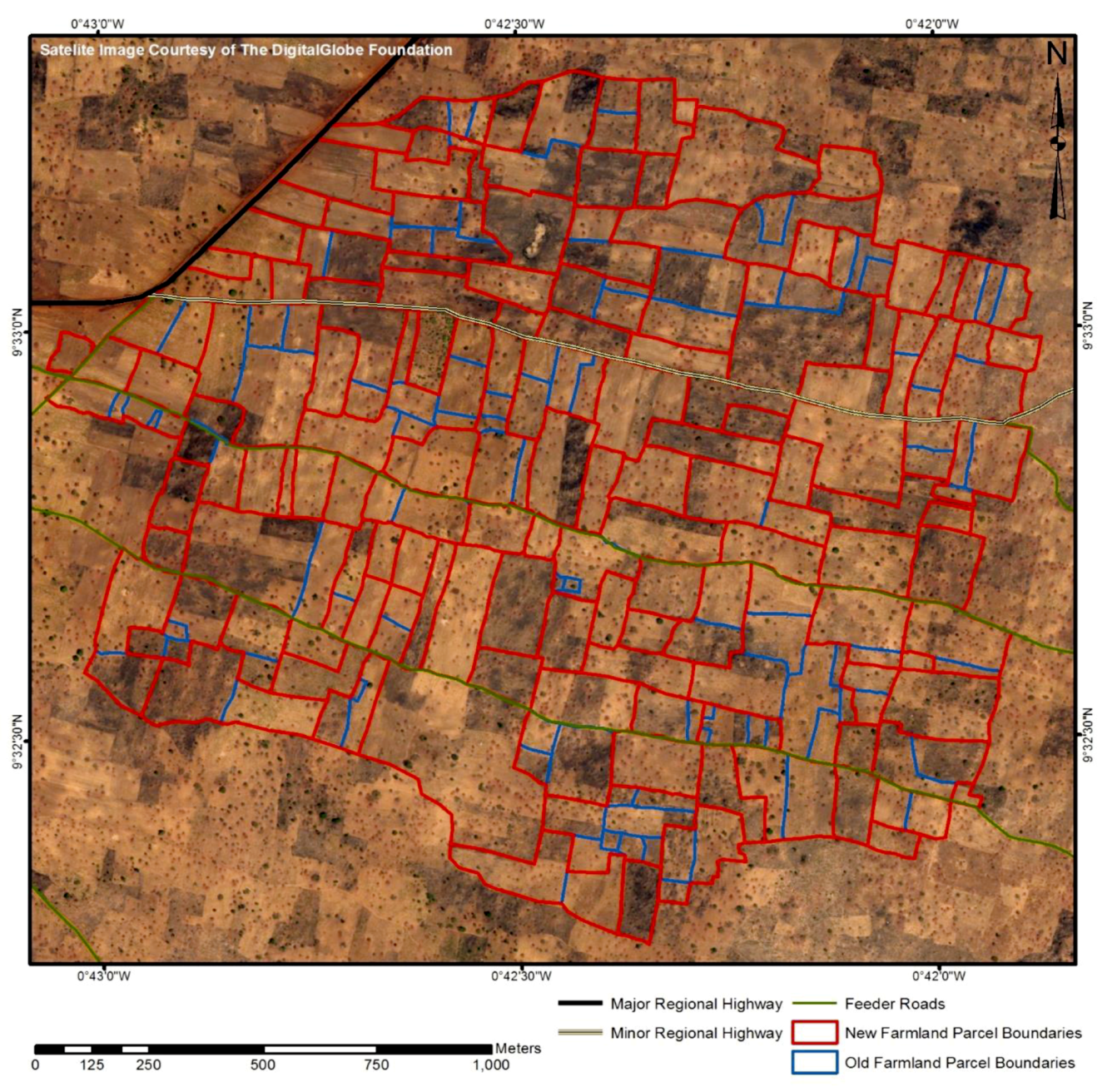

The experiment into PLA in Nanton, Ghana was assessed in terms of reliability, affordability, local participation, and attainability. In terms of reliability, it was found that both technologies, the smartphone app and satellite image were easy for the farmers to use, as the majority of them were users of smartphones. The accuracy of the mobile app ranged between 1 and 3 m, which even though it is not adequate for the land title registration in Ghana, is enough for the recording of land rights in rural areas. No boundary disputes were encountered. The mobile app was further able to capture all 230 farmland parcels in the area, though the identification on the satellite yielded 143 parcels (

Figure 6). The former was further able to identify and collect information on all the customary land rights that are related to farming. In terms of affordability, the two technologies used together are found to be cheaper to use than the current approaches on customary lands. Whereas the current conventional and innovative approaches in Ghana cost at least GH¢ 500 (EUR 125) and GH¢ 200 (EUR 20) per parcel, this approach is estimated to cost GH¢ 36.83 (EUR 9.24) per parcel. This cost will reduce with scaling up. In terms of local participation, it was found that the local people were involved in every step of the approach. This according to them gave them a sense of ownership of the data and the process. The involvement of the Trusted Intermediaries further created a layer of check for the information collected. In terms of attainability, the experiment took 10 working days, roughly 20 minutes per parcel. This would however reduce when the interviews and focus group discussions for the assessment of the process is excluded. The process is therefore fast. The use of locally acquired and accessible materials further boosted the ability of the local people to replicate the process.

Even though the experiment did not set out to undertake a full land consolidation, it is found capable of capturing all customary land rights as well as other information relevant to land consolidation. The detailed results of this objective may be found in Asiama et al. [

72].

5.3. Valuation of Farmlands for Land Consolidation

Land value is not explicit on rural customary lands, mostly because the social, cultural, and spiritual bonds with land inhibit the free operation of a land market. Land reallocation in land consolidation relies on land valuation to describe and assign a value to the farmlands that will be reflective of the farmers’ perception of their farmland values. The traditional valuation approaches, including the cost, investment, and comparative methods, are used to value customary lands. However, in rural areas, it is found that even though the sales of land are very uncommon and unlikely, where land is rented out, the money that exchanges hands is a flat rate that is charged regardless of the nature of the farmland parcel.

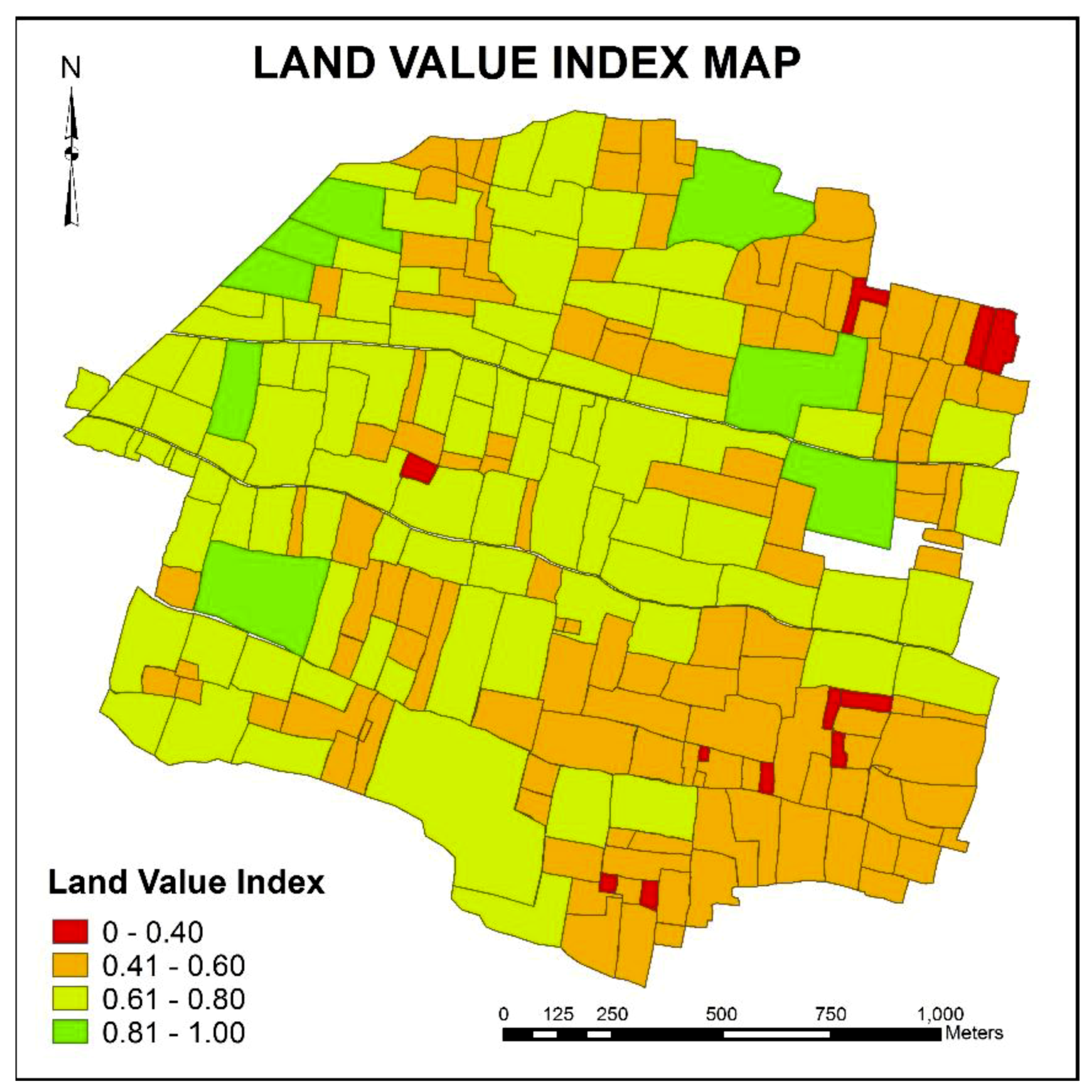

There are two approaches to land valuation in land consolidation—the agronomic value, with its basis being the soil productivity and quality, and the market value. Alternatively, market value has been touted as the better approach with studies pointing out the deficiencies in the agronomic value approach. However, the market value approach cannot be used in sub-Saharan Africa’s customary lands due to the limited land market. Here, a framework was developed for an approach for assigning values to customary rural farmland parcels that reflects the local people’s view of land value. Land value indices are used here instead of scores to allow for continuous values in comparison instead of discrete values through a flexible and content-specific approach that allows replication in other contexts. The approach is knowledge-based, using local and expert judgement through value functions. LVIs measures how far land value factors LVFs), that influence land value, deviate from the most suitable farming conditions, here denoted as one, or the worst, here being zero. To identify and understand the factors that affect farm-land value on rural customary lands, the factors found in previous studies relating to the valuation of other types of land were identified. The LVFs are first assigned scores through a quantitative method for the continuous variables, or a categorical rating method for discrete variables using the appropriate ordinal scale. These scores are derived from expert and local judgement. The scores of the factors were standardized using the direct value rating to allow for comparison on the scale.

The land value index (LVI) for each parcel is calculated by multiplying the standardised score of each factor (

Sfp) by the corresponding weight of the factor (

Wf), and summing for each farmland parcel, as depicted in the equation function below;

It was found in the case study of Nanton that key land value factors that determine land values relate to the physical attributes, legal conditions, agricultural productivity, locational factors, and the planning scheme of the farmland parcels (

Figure 7). These factors were weighted by the local community according to their perception of what affected their choice of farmland parcels. The weights were integrated into the framework that produced the land value index (LVI) for each land parcel in the area of study. The results showed that in a scenario analysis, a change in weights affected the land value indices at a scale that could change the comparative basis of the land parcels. The sensitivity analysis however showed that the LVIs were not significantly sensitive to the changes in the weight of the factors. However, a prime weakness of this framework is that it is more expensive to use than automatic valuation models. The results demonstrate that it is possible to place relative quid pro quo values on rural agricultural farmlands that are not part of a land market. These quid pro quo values will serve as a basis for the reallocation of the farmland parcels. The detailed results of this objective may be found in Asiama et al. [

73].

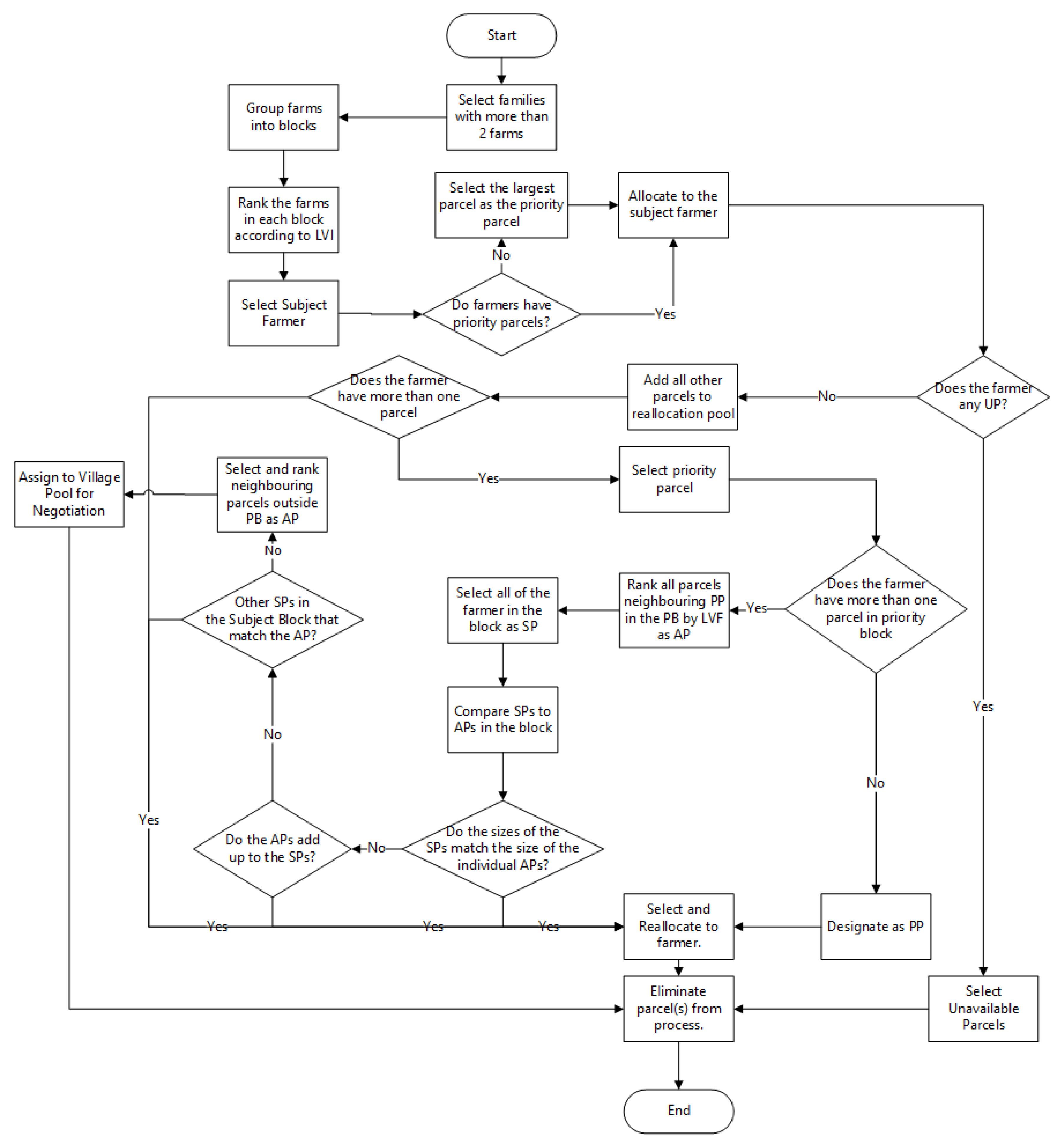

5.4. Land Reallocation for Customary Lands

The results of the previous two sections were synthesised to develop the framework of a land reallocation model. Land reallocation is seen as the most important stage in the land consolidation process, where property rights are exchanged, and farmland parcels are redistributed and reorganised. A model of land reallocation should therefore consider all related land information (spatial, rights, and value) and the wishes of the involved land holders. The framework for the model is developed using a process model taking into consideration the social, economic, cultural, technical, and political considerations on customary lands, through the steps of analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

The undertaking of land reallocation generally has three key requirements and considerations. Politically, land reallocation requires a mediating authority to act as an arbitrating force during the planning and implementation, because of the disputes that land reallocation may spark. Similar to land consolidation in general, land reallocation also requires a level of land mobility that will allow for the exchange of farmland parcels, in this case related to social land mobility, i.e., land mobility based on the social and cultural norms in the community. The development of a land reallocation model further requires a consideration for the land tenure system and the land fragmentation situation. Customary lands characteristics that are relevant to land reallocation relate to the rules that relate to the transfer of land between two parties. Here, even though it is generally accepted that customary lands cannot be transferred, it is found that customary land tenure rules do indeed allow for the transfer of land, but with strict restrictions. The framework of the land reallocation model is built around the legal and technical aspects of land reallocation, taking into consideration the levels of landholding (individual, family/clan, village, etc.). The framework for the land reallocation is focused on the family level as

Section 5.1 shows that transfer of lands within families involves only the individuals concerned. However, where land is transferred outside the family, it requires the consent of the two families.

Figure 8 below shows the flowchart of the land reallocation framework.

When the model framework was applied to the area of interest, it was found that physical land fragmentation was significantly reduced, with a reduction in the number of farmland parcels, an increase in the parcel sizes, a reduction in the land tenure fragmentation, an increased accessibility to key lines of transportation, and slight improvement in the parcel shapes in the area, even though this was not a goal of the approach. The most appropriate central mediating authority in the area was found to be the traditional authority in the area, much different from the other areas in the world where land re-allocation has been done.

Figure 9 shows a change detection map of the area of interest before and after the land reallocation.

Table 1 also summarises the effects of the land reallocation.

In terms of the land tenure system, local customs, and land mobility, the study found the relationship between the tenant and the usufruct to be a key cause of land tenure fragmentation. However, the study further showed that land tenure fragmentation would be reduced with the application of the approach. With regards to the land reallocation between families, it was found that the developed approach could not handle this as the local people were vehemently against families parting with their sub-allodial interests in land, even when it is swapped for a similar parcel of land. The only seeming solution was to rent out the family land to serve the purposes of re-allocation. However, although this would reduce the physical land fragmentation, the land tenure fragmentation would worsen. The detailed results of this objective may be found in Asiama et al. [

74].

7. Conclusions

This study aimed at developing a responsible approach to land consolidation on customary lands, using Ghana as a case. The study found that in a comparison between countries with a responsible land consolidation (Rwanda, Lithuania, and the Netherlands) on one hand and a country with customary lands but without a land consolidation (Ghana) on the other hand, there were three areas that needed attention to develop a responsible land consolidation the land administration processes, the land valuation approach, and the land reallocation approach. The participatory land administration (PLA) was developed to bring together traditional land administration approaches, deeply rooted in western views, together with bottom-up emerging approaches that challenge traditional approaches, as well as technological advances that drive these approaches together with the growing societal needs. A valuation approach was then developed to enable the comparison of the farmlands in rural areas that are without land markets. Finally, a land reallocation approach was developed based on the political, economic and social, as well as technical and legal characteristics of rural customary farmlands. This study finds that though the land consolidation strategy developed is significantly able to reduce land fragmentation, both physical and land tenure, the local customs are an obstruction to the technical processes to achieve the best form of farm structures. However, the consideration of all aspects of the society and technology being a basic tenet of responsible approaches, the changes to the local customs is beyond the scope of this study.

A further comparative study can be undertaken on other SSA countries’ rural customary lands to further understand the differences, in terms of the requirements of land consolidation. In addition, future work should focus on further developing land valuation and land reallocation approaches by automating them using Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA) systems with GIS, and Spatial Decision Support Systems (SDSS), respectively. This is because the processes developed in this study were generalised processes that exist in other regions of the world. The valuation approach was developed in the rural farming context, it can therefore also be developed further looking at urban land to put it in a broader context. This will further deepen and enrich the use of market information in the valuation of urban lands, especially for slum areas for non-market values. Furthermore, as shown in

Section 5.1, customary lands are independently managed in each community, saved for the national legal framework that tries to harmonise their management. This means that a single land consolidation approach will not fit the whole country. Further research should therefore be conducted into the legal framework of Ghana, vis á vis land consolidation in order to develop an integrated, flexible, and inclusive framework for customary lands towards land consolidation. Further research also needs to be done in the implementation, through active research in the conduct of a pilot land consolidation process in the customary areas, to further ascertain the limitations that the approaches have in other areas. This, in tandem with the scaling up approach by further establishing workflows, will enable the testing of the approach with a wider coverage.