Navigating Multiple Tensions for Engaged Praxis in a Complex Social-Ecological System

Abstract

1. Introduction

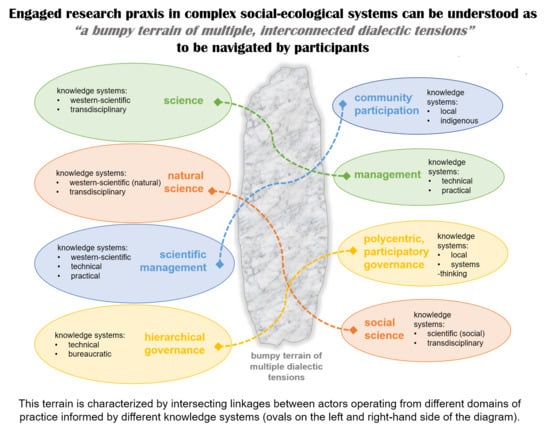

Conceptual Framing: Reflexive Research Praxis in Complex Social-Ecological Systems

2. The Case of the Tsitsa Project

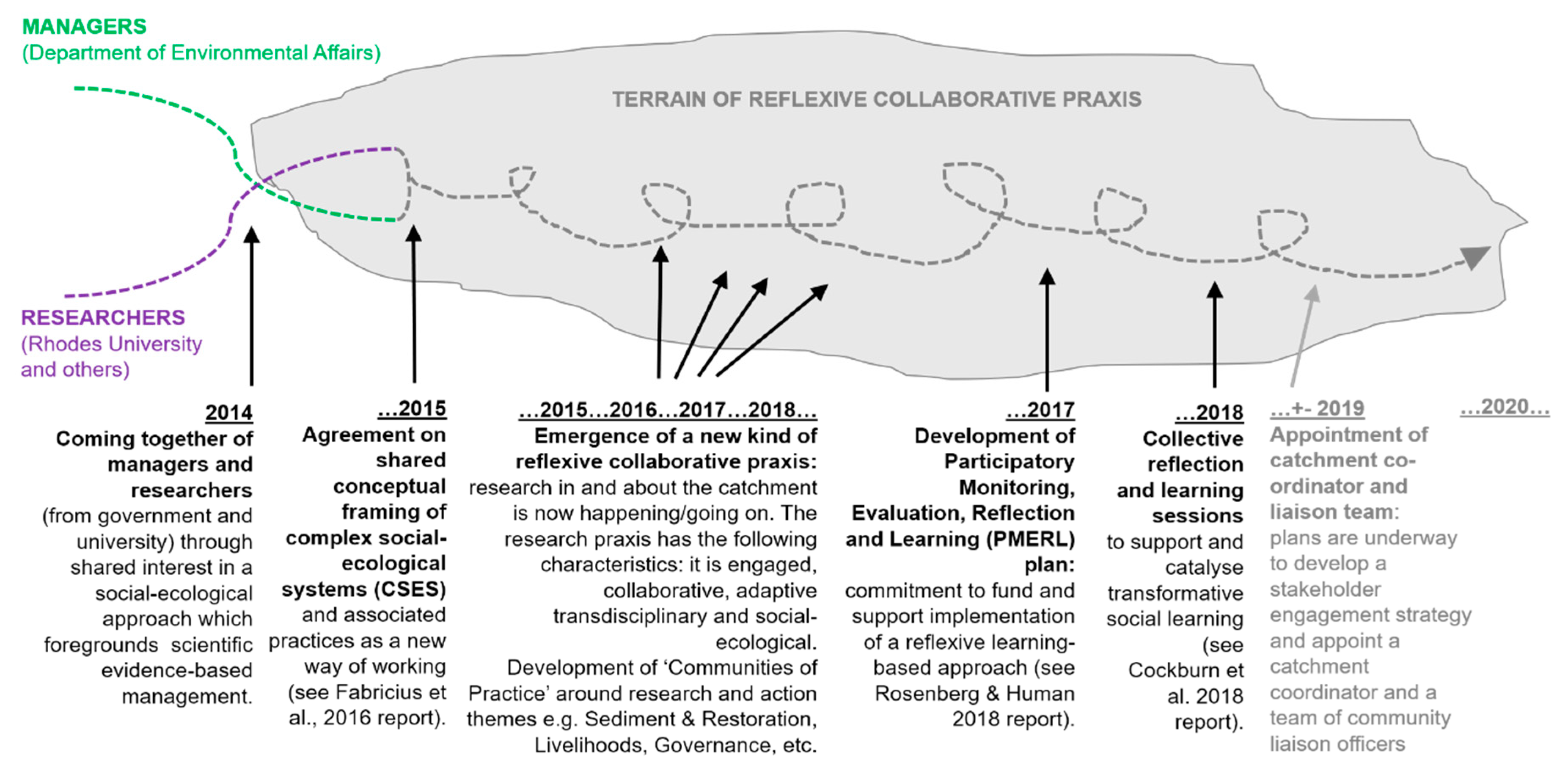

2.1. What Is the Tsitsa Project and How Did It Arise?

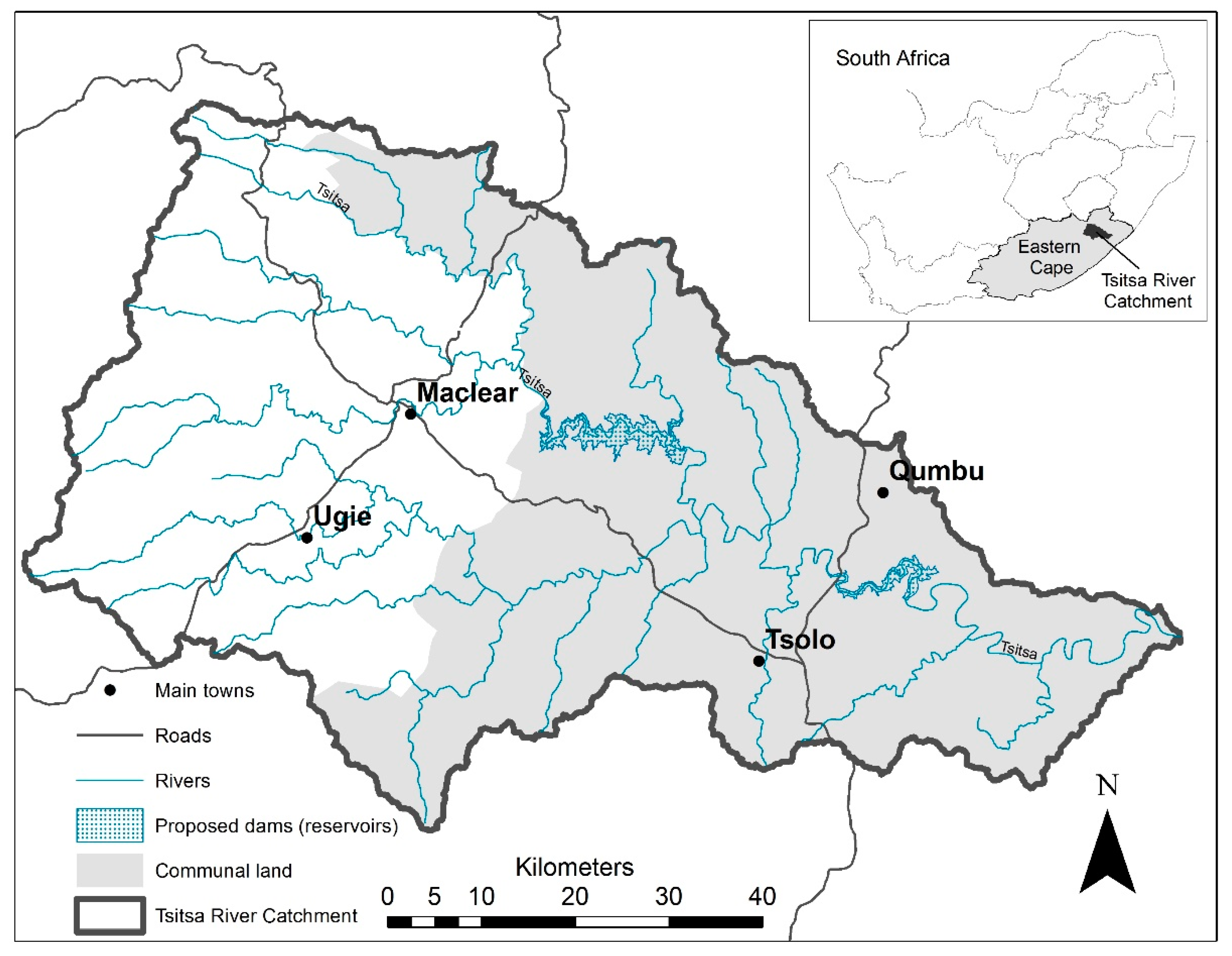

2.2. The Social-Ecological Context of the Tsitsa River Catchment

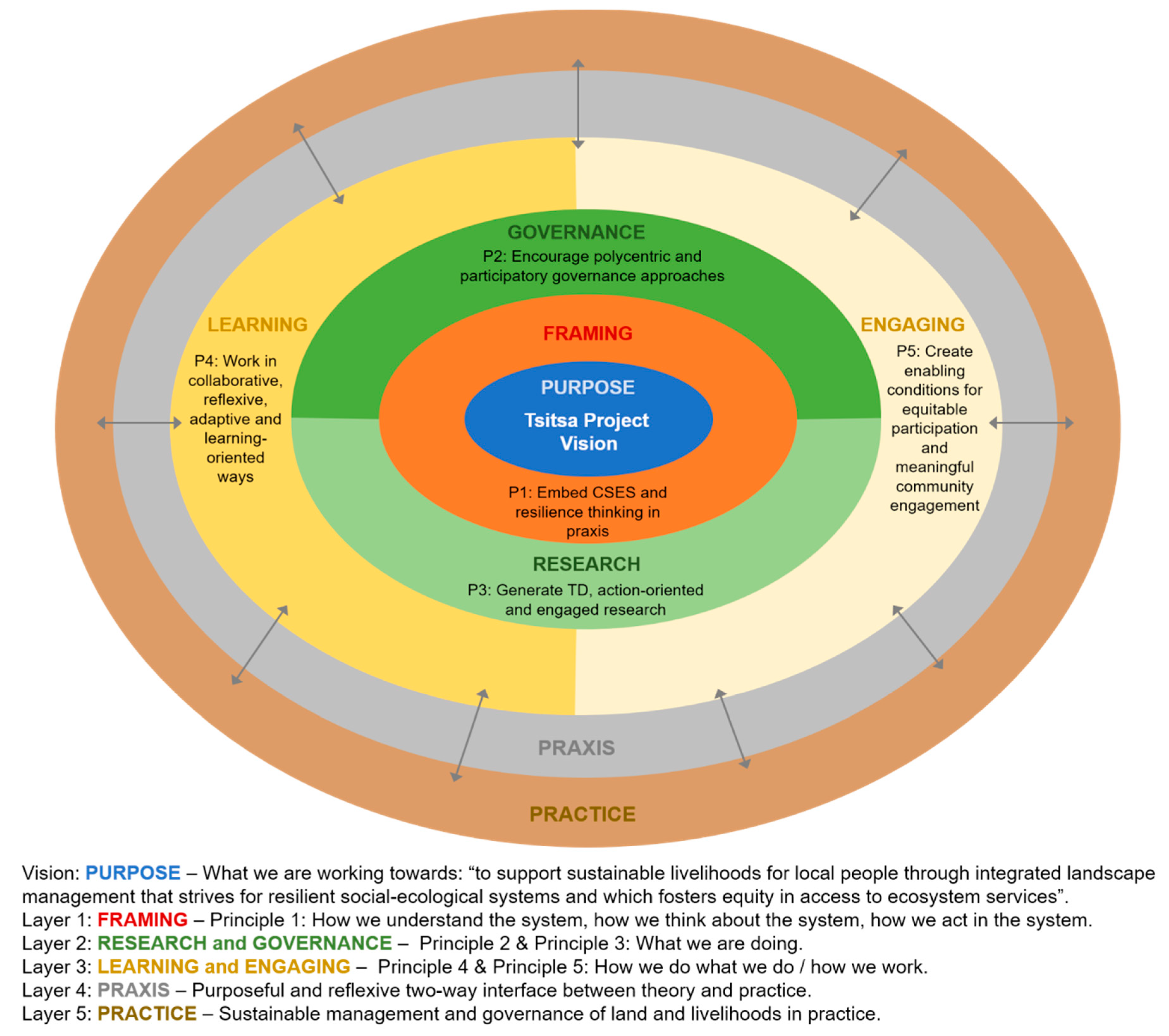

2.3. How the Tsitsa Project Works

- Political and high-level administrative will to support and give the Tsitsa Project a fair chance: DEA: NRM has treated the Project from early on as a flagship initiative or “experiment” and given it the requisite partial freedom and space to attempt innovations in research, management, governance and practical interventions.

- Widening learning linked to parallel processes: Prior to the Tsitsa Project, and parallel to its development, DEA: NRM have conducted their own science and management planning meetings on a regular basis which have laid a foundation for leading officials transitioning from project managers to social and institutional entrepreneurs who mediate multi-party initiatives.

- Multi-scale and expanding nature of the initiative and its impact: multiple connected scales and levels of operation and governance influence Project activities; the ambitious nature of the scale makes this an imperative but also a challenge.

- Appreciation for systems features such as novelty and serendipity: There is a sense of novelty and serendipity arising from enabling leaders (including many experienced practitioners, scientists, administrators, and now wise community elders) to share ideas and co-construct potential ways forward.

- Openness to collective learning: Much of the evolution and progress in the Project is based on learning from inter-personal and especially inter-group interactions and shared experiences, rather than being ideologically rooted in some “external” idea or recipe. This requires pragmatism based on lively ongoing reflection and a commitment to adaptive practice.

- Enthusiasm for the complex and daunting task among participants: This upbeat attitude is an essential enabler and incentive for working in such a complex and challenging context.

3. Methodology

3.1. Critical Realism as an Underpinning Philosophy

3.2. Elucidating Principles to Guide Reflection and Analysis

3.3. Research Design and Methods

4. Findings

4.1. Findings Regarding the Guiding Principles of the Tsitsa Project

4.2. Lessons Learnt about Principles through Praxis

“This is an ambitious and ground-breaking project and I am excited about participating as it appeals to my personal commitment to doing meaningful work that can bring about change.”

“There is willingness in NLEIP and we are trying to implement the work according to the principles but it is difficult and, in many cases, constrained by external barriers.”

“It takes time … and money … and the right people … to work according to CSES principles … to build trust … to build relationships … to work reflexively and adaptively … to build polycentric governance … to put all these principles into practice.”

“The focus on polycentric governance is probably the most important work. It is the most challenging but it has the potential to bring about the most significant and sustainable change in the catchment.”

“There has recently been a shift in the Tsitsa Project: the dominance of “science” has somewhat decreased. For a long time, the science voices were loudest in the room but now there is a stronger sense of purpose and understanding of what we are doing, there is better cross-pollination and integration (e.g., among CoP and also between scientists and managers) and there is a clearer focus on tangible local actions.”

“The links between research and management have been unclear and confusing, and the lines of command/responsibility/communication between researchers and managers/implementers has not always been clear, though this is getting better.”

“Community engagement and facilitation are a priority and concern. Some effort is being made in this regard but it seems that the current effort is insufficient or is not working.”

“Sufficient budget must be put aside to have a community engagement team in the catchment to build trust and long-term relationships with local communities. The social side of things cannot be an afterthought.”

4.3. From Reflection Data to Meaning-Making and Learning

4.3.1. Social-Ecological Systems and Resilience Thinking, and Recognition of Guiding Principles, Have Created an Enabling Framing

4.3.2. Building Novel Linkages among Diverse Actors in the CSES is a Challenge

4.3.3. Existing Institutional Structures, Cultures and Ways of Working Impose Significant Constraints

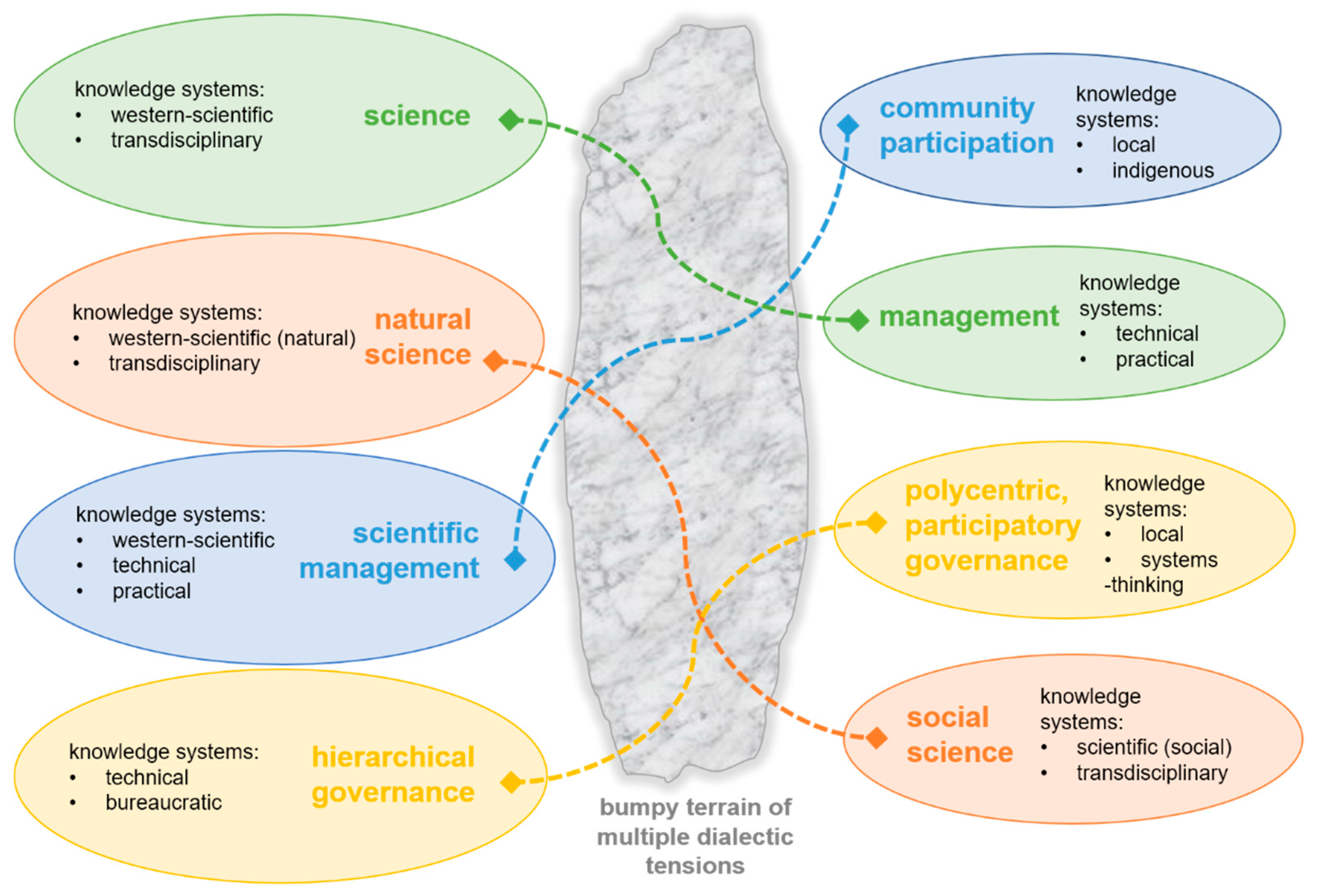

5. Discussion: An Explanatory Metaphor of Wider Relevance—Navigating a Bumpy Terrain of Dialectic Tensions

- Develop context-specific communication, advocacy, community engagement and knowledge management strategies: this may be outside the comfort zone or expertise of participants (e.g., scientists and managers with training in natural resource management), however projects should partner with others to get new expertise into the team. This may require re-allocation of funding away from research, or alternative sources of funding, for example, the Tsitsa Project is investigating partnering with NGOs with expertise in rural development and agricultural extension; funding has been allocated for development of communication, community engagement and knowledge management strategies; plans are underway to appoint a local catchment co-ordinator and team of liaison officers to improve communication and engagement in the catchment and to better embed the initiative in the catchment.

- Investigate potential adjustments to incentive structures both for managers and scientists: for example, for scientists: university awards and promotion criteria which incentivise community-engaged and change-oriented research (this is already becoming more prevalent at Rhodes University); for managers: develop ‘Key Performance Indicators’ which recognise managers spending time in engaged, collaborative processes, not only those which count ‘hard’ outcomes such as number of hectares of invasive plants cleared, number of jobs created and so forth. The Tsitsa Project still needs to reflect further on the role of incentives in supporting the potentially transformative work of the project, especially since we envisage expanding roles for participants.

- 3.

- Carefully design for and support reflexive praxis: make time and space for reflection and embed Participatory Monitoring Evaluation Reflection and Learning (PMERL) throughout the activities of the project by aligning reflection with other activities and appointing staff to manage and implement PMERL for example, the Tsitsa Project has recently appointed a PMERL co-ordinator; informal and fun reflection sessions take place after meetings over a cup of coffee or a drink before everyone heads home; participants are encouraged to reflect together while travelling to and from the catchment.

- 4.

- Pay attention to the development of new inter-personal relationships beyond formal work activities to enable boundary-spanning and learning: relationships of trust often deepen, enabling deeper reflection and learning, when participants interact ‘after hours’ or in a less formal setting other than a meeting. Therefore, we suggest structured activities for people to work together on something non-trivial but also not too daunting, for example, in the Tsitsa Project we plan to conduct collective in-field restoration or monitoring activities; and host social activities like ‘braais’ (barbeques) where scientists, managers and catchment residents can get to know each other and explore their shared values.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Luckert, M. Changing Livelihoods and Landscapes in the Rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: Past Influences and Future Trajectories. Land 2015, 2015, 1060–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, S. Development and sustainable management of rangeland commons—Aligning policy with the realities of South Africa’s rural landscape. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2013, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C. Will the real custodian of natural resource management please stand up. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2009, 105, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R.; Rhode, C.; Archibald, S.; Kunene, L.M.; Mutanga, S.S.; Nkuna, N.; Ocholla, P.O.; Phadima, L.J. Strategies for managing complex social-ecological systems in the face of uncertainty: Examples from South Africa and beyond. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Biggs, H.; Braack, M.; Ntabelanga and Lalini Ecological Infrastructure Project team. Ntabelanga and Lalini ecological infrastructure project. In A Better World Volume 3: Ensure Access to Water and Sanitation to All. Actions and Commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals; Nicklin, S., Cornwell, B., Trowbridge, L., Eds.; Tudor Rose: Leicester, UK, 2018; pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C.G.; Biggs, R.; Cumming, G.S. Applied research for enhancing human well-being and environmental stewardship: Using complexity thinking in Southern Africa. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ison, R.; Collins, K.; Colvin, J.; Jiggins, J.; Roggero, P.P.; Seddaiu, G.; Steyaert, P.; Toderi, M.; Zanolla, C. Sustainable Catchment Managing in a Climate Changing World: New Integrative Modalities for Connecting Policy Makers, Scientists and Other Stakeholders. Water Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 3977–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margerum, R.D. A Typology of Collaboration Efforts in Environmental Management. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, D.J.; Foxcroft, L.C. The development and application of strategic adaptive management within South African National Parks. Koedoe 2011, 53, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, R.T.; Biggs, H.C.; Pollard, S.R. Strategic Adaptive Management in freshwater protected areas and their rivers. Boil. Conserv. 2011, 144, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, G.; Rodela, R. A review of assertions about the processes and outcomes of social learning in natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ison, R. Governing the human-environment relationship: Systemic practice. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning in a changing world and changing in a learning world: Reflexively fumbling towards sustainability. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Mukute, M.; Belay, M. The ‘social’ and ‘learning’ in social learning research: Avoiding ontological collapse with antecedent literatures as starting points for research. In (Re)views on Social Learning Literature: A Monograph for Social Learning Researchers in Natural Resources MANAGEMENT and Environmental Education; Lotz-Sisitka, H., Ed.; Environmental Learning Research Centre, Rhodes University/EEASA/SADC REEP: Grahamstown/Howick, South Africa, 2012; pp. 56–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, D.J.; Nel, J.L.; Cundill, G.; O’Farrell, P.; Fabricius, C. Transdisciplinary research for systemic change: Who to learn with, what to learn about and how to learn. Sustain. Sci 2017, 12, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; Kinti, I. Working relationally at organisational boundares: Negotiating expertise and identity. In Activity Theory in Practice: Promoting Learning across Boundaries and Agencies; Daniels, H., Edwards, A., Engeström, Y., Gallagher, T., Ludvigsen, S.R., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010; pp. 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.-G.; Creed, W.E.D. Institutional Contradictions, Praxis, and Institutional Change: A Dialectical Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, J.; Biggs, H.; Rosenberg, E.; Palmer, C.G. Tsitsa Project Learning Report 2018. Learning through Reflective Praxis: Lessons from Integrated Sustainability Research with a Governance Focus in a Complex Social-Ecological System, Eastern Cape, South Africa; Tsitsa Project Internal Report; Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius, C.; Biggs, H.C.; Powell, M. Research Investment Strategy: Ntabelanga and Lalini Ecological Infrastructure Project (NLEIP); Department of Environmental Science, Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, H.C.; Breen, C.; Slotow, R.; Freitag, S.; Hockings, M. How assessment and reflection relate to more effective learning in adaptive management. Koedoe 2011, 53, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilgen, B.W.; Wannenburgh, A. Co-facilitating invasive species control, water conservation and poverty relief: Achievements and challenges in South Africa’s Working for Water programme. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 19, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T.L.; Shackleton, R.T.; Förster, J.; Dini, J.; Khan, A.; Gumula, M.; Kubiszewski, I. Achieving the national development agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through investment in ecological infrastructure: A case study of South Africa. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bek, D.; Nel, E.; Binns, T. Jobs, water or conservation? Deconstructing the Green Economy in South Africa’s Working for Water Programme. Environ. Dev. 2017, 24, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwada, C.; Van Tol, J. The nature of soil erosion and possible conservation strategies in Ntabelanga area, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2016, 66, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, J.J. Sediment Yield Potential in South Africa’s Only Large River Network without a Dam: Implications for Water Resource Management. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Manjarrés, J.F.; Roturier, S.; Bilhaut, A.-G. The emergence of the social-ecological restoration concept. Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwela, A.; Elbakidze, M.; Powell, M.; Angelstam, P. Defining core areas of ecological infrastructure to secure rural livelihoods in South Africa. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tol, J.; Akpan, W.; Kanuka, G.; Ngesi, S.; Lange, D. Soil erosion and dam dividends: Science facts and rural ‘fiction’ around the Ntabelanga dam, Eastern Cape, South Africa. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2016, 98, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E.; Human, H. Tsitsa Project Participatory Monitoring, Evaluation, Reflection and Learning Inception Document, April 2018; Environmental Learning Research Centre, Rhodes University Grahamstown: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cundill, G.; Roux, D.J.; Parker, J.N. Nurturing communities of practice for transdisciplinary research. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannatyne, L.; Rowntree, K.; van der Waal, B.; Nyamela, N. Design and implementation of a citizen technician–based suspended sediment monitoring network: Lessons from the Tsitsa River catchment, South Africa. Water SA 2017, 43, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisitka, L.; Ntshudu, M.; Hamer, N.; de Vos, A. Ntabelanga (Laleni) Stakeholder Analysis Report for the DEA: NRM Branch—Ntabelanga Lalini Ecological Infrastructure Project; Tsitsa Project Internal Report; Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, N.; Burt, J.; Ntshudu, M.; Mtati, N.; Lunderstedt, K. Lalini Rapid Stakeholder Analysis Report; Tsitsa Project Internal Report; Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, F.; Guillermin, M.; Dedeurwaerdere, T. A pragmatist approach to transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: From complex systems theory to reflexive science. Futures 2015, 65, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J. Explanatory Mechanisms: The Contribution of Critical Realism and Systems Thinking/Cybernetics; Working Paper No. 241; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Audouin, M.; Preiser, R.; Nienaber, S.; Downsborough, L.; Lanz, J.; Mavengahama, S. Exploring the implications of critical complexity for the study of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K.H.; Luton, R.; Biggs, H.; Biggs, R.; Blignaut, S.; Choles, A.G.; Palmer, C.; Tangwe, P. Fostering Complexity Thinking in Action Research for Change in Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P. Integrative Analysis Strategies for Mixed Data Sources. Am. Behav. Sci. 2011, 56, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. NVivo 11 for Windows. Edition: Pro.; QSR International, Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, G.; Morrison, P.; Down, B.; WestBrook, B. Scaffolding young Australian women’s journey to motherhood: A narrative understanding. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazeley, P. Analysing qualitative data: More than ‘identifying themes’. Malays. J. Qual. Res. 2009, 2, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Danermark, B.; Ekström, M.; Jakobson, L.; Karlson, J.C. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, H.; Clifford-Holmes, J.K.; Conde-Aller, l.; Lunderstedt, K.; Mtati, N.; Palmer, C.G.; Powell, M.; Rosenberg, E.; Rowntree, K.; van der Waal, B.; et al. The Tsitsa Project (Previously NLEIP*) Research & Praxis Strategy: Resource Library (Version 2) Informing Plans for 2018–2021; Department of Environmental Science, Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, in preparation.

- Biggs, D.; Abel, N.; Knight, A.T.; Leitch, A.; Langston, A.; Ban, N.C. The implementation crisis in conservation planning: Could “mental models” help? Conserv. Lett. 2011, 4, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Biggs, D.; Bohensky, E.L.; Burnsilver, S.; Cundill, G.; Dakos, V.; Daw, T.M.; Evans, L.S.; Kotschy, K.; et al. Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, J.; Cundill, G.; Shackleton, C.; Rouget, M. Towards Place-Based Research to Support Social-Ecological Stewardship. Sustainability 2018, 10, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Mostert, E.; Tàbara, D. The Growing Importance of Social Learning in Water Resources Management and Sustainability Science. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level—And effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.G.; Munnik, V. Practising Adaptive IWRM (Integrated Water Resources Management) in South Africa: Report to the Water Research Commission; WRC Report No. 2248/1/18; Water Research Commissionl: Gezina, South Africa, 2018; Available online: http://www.wrc.org.za/Knowledge%20Hub%20Documents/Research%20Reports/2248-1-18.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Biggs, H.C.; Clifford-Holmes, J.K.; Freitag, S.; Venter, F.J.; Venter, J. Cross-scale governance and ecosystem service delivery: A case narrative from the Olifants River in north-eastern South Africa. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.W.; Ross, H.; Bellamy, J. Managing wicked natural resource problems: The collaborative challenge at regional scales in Australia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 154, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kerkhoff, L. Developing integrative research for sustainability science through a complexity principles-based approach. Sustain. Sci 2014, 9, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, D.J.; Stirzaker, R.J.; Breen, C.M.; Lefroy, E.C.; Cresswell, H.P. Framework for participative reflection on the accomplishment of transdisciplinary research programs. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, N.G.; Lipile, L.; Lipile, M.; Molony, L.; Nzwana, X.; O’Keeffe, J.; Shackleton, S.E.; Weaver, M.; Palmer, C.G. Coping with water supply interruptions: Can citizen voice in transdisciplinary research make a difference. Water Int. 2018, 43, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, J.; Rouget, M.; Slotow, R.; Roberts, D.; Boon, R.; Douwes, E.; O’Donoghue, S.; Downs, C.T.; Mukherjee, S.; Musakwa, W.; et al. How to build science-action partnerships for local land-use planning and management: Lessons from Durban, South Africa. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.; Chan, S.; Santelmann, M.V.; Tilt, B. Transdisciplinary research in water sustainability: What’s in it for an engaged researcher-stakeholder community? Water Altern. 2018, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breda, J.; Swilling, M. The guiding logics and principles for designing emergent transdisciplinary research processes: Learning experiences and reflections from a transdisciplinary urban case study in Enkanini informal settlement, South Africa. Sustain. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Yaffee, S.L. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons From Innovation In Natural Resource Managment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, L.C.; Dougill, A.J.; Fraser, E.; Hubacek, K.; Prell, C.; Reed, M.S. Unpacking “Participation” in the Adaptive Management of Social-ecological Systems: A Critical Review. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, P.; Ernst, A.; Gralla, F.; Luederitz, C.; Lang, D.J.; Newig, J.; Reinert, F.; Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H. A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, T.; Maynard, C.; Carr, G.; Bruns, A.; Mueller, E.N.; Lane, S. A transdisciplinary account of water research. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2016, 3, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillman, M. Justice in River Management: Community Perceptions from the Hunter Valley, New South Wales, Australia. Geogr. Res. 2005, 43, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E.; Biggs, H. NLEIP Ecological Infrastructure Programme: The Learning Journey. Conference Presentation. In Proceedings of the Adaptation Futures Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 19 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bartunek, J.M.; Rynes, S.L. Academics and Practitioners Are Alike and Unlike: The Paradoxes of Academic–Practitioner Relationships. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1181–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Learning towards a Sustainable World; Wals, A.E.J.E., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. Purposeful collective action in ambiguous and contested situations: Exploring ‘enabling capacities’ and cross-level interplay. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Orozco, B.; Rosell, J.; Merçon, J.; Bueno, I.; Alatorre-Frenk, G.; Langle-Flores, A.; Lobato, A. Challenges and Strategies in Place-Based Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainability: Learning from Experiences in the Global South. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Brondizio, E.S.; Elmqvist, T.; Malmer, P.; Spierenburg, M. Connecting Diverse Knowledge Systems for Enhanced Ecosystem Governance: The Multiple Evidence Base Approach. AMBIO 2014, 43, 579–591. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, J.K. Organizations: A dialectic view. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. Dialectic: The Pulse of Freedom; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Norrie, A. Dialectic and Difference: Dialectical Critical Realism and the Grounds of Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, J.J. Stewardship and Collaboration in Multifunctional Landscapes: A Transdisciplinary Enquiry. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Environmental Science, Rhodes Universit, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10962/61267 (accessed on 23 October 2018).

- Rosenberg, E.; Rosenberg, G.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.B.; Ramsarup, P. Green Economy Learning Assessment South Africa. Critical Competence for Driving a Green Transition; PAGE: Partnership for Action on Green Economy: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F.R.; Tjornbo, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Crona, B.; Bodin, Ö. A Theory of Transformative Agency in Linked Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R.L.; Steyaert, P.; Roggero, P.P.; Hubert, B.; Jiggins, J. The SLIM (Social Learning for the Integrated Management and Sustainable Use of Water at Catchment Scale) Final Report. The SLIM Project. 2004. Available online: http://slim.open.ac.uk (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Leeuwis, C. Communication for Rural Innovation: Rethinking Agricultural Extension; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Tsitsa Project was previously known as the NLEIP: Ntabelanga and Lalini Ecological Infrastructure Project (2014–2018). The name change occurred in mid-2018. |

| 2 | Although the initiative aims for ecological restoration of land, within the current scope of the project, the term rehabilitation may be more realistic. |

| 3 | Note we use the word ‘dam’ as it is used in South African English to refer to the reservoir and the dam as a unit. |

| 4 | Upon further reflection after completion of our data collection and analysis, the Tsitsa Project team decided to adjust these principles for publication in its updated Research Investment Strategy (RIS Version 2), which is still in preparation. The main difference between the five principles presented here and those in the RIS Version 2 is the addition of a principle labelled “Scientific-technical foundation and evidence base,” which foregrounds the role of scientific knowledge in supporting management and governance of the catchment [48]. |

| 5 | Narrative threads are composite quotes used to illustrate general discourse and themes among participants by combing a number of verbatim quotes into one statement. |

| Tsitsa Project Guiding Principles | Project Participants’ Perceptions of the Principle in Praxis 1 | Key Lessons Learnt about the Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Principle 1: Embed complex social-ecological systems and resilience thinking in praxis | This is the principle which most participants seem to understand, identify with, and actively try to practice in their work. It sets the scene for the other principles. |

|

| Principle 2: Encourage polycentric and participatory governance approaches | Some participants were unfamiliar with this concept. The leaders of the initiative, however, are passionate about it and believe it to be the biggest challenge but also potentially the biggest contribution of the Tsitsa Project. |

|

| Principle 3: Generate transdisciplinary, action-oriented and engaged research | Transdisciplinary research among scientists is considered to be on track, even if not yet entirely successful. However, the move from inter- to transdisciplinarity, and engaged and action-oriented aspects need further attention. |

|

| Principle 4: Work in collaborative, reflexive, adaptive and learning-oriented ways | Collaboration, reflection and adaptation between scientists is going well, links between scientists and managers are slowly improving. But links to other catchment stakeholders and community members are still lacking. |

|

| Principle 5: Create enabling conditions for equitable participation by multiple stakeholders with a particular commitment to meaningful engagement with local communities | Most participants feel we are not doing enough to implement this principle. Community engagement has been ad-hoc and only focused on traditional leaders, thereby marginalizing the less powerful. Lack of engagement with other government stakeholders is also a concern. |

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cockburn, J.; Palmer, C.G.; Biggs, H.; Rosenberg, E. Navigating Multiple Tensions for Engaged Praxis in a Complex Social-Ecological System. Land 2018, 7, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040129

Cockburn J, Palmer CG, Biggs H, Rosenberg E. Navigating Multiple Tensions for Engaged Praxis in a Complex Social-Ecological System. Land. 2018; 7(4):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040129

Chicago/Turabian StyleCockburn, Jessica, Carolyn (Tally) G. Palmer, Harry Biggs, and Eureta Rosenberg. 2018. "Navigating Multiple Tensions for Engaged Praxis in a Complex Social-Ecological System" Land 7, no. 4: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040129

APA StyleCockburn, J., Palmer, C. G., Biggs, H., & Rosenberg, E. (2018). Navigating Multiple Tensions for Engaged Praxis in a Complex Social-Ecological System. Land, 7(4), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040129