Abstract

The paper investigates whether farm dwellers in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province of South Africa are subject to a “double exposure”: vulnerable both to the impacts of post-apartheid agrarian dynamics and to the risks of climate change. The evidence is drawn from a 2017 survey that was undertaken by the Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA), which is a land rights Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), of 843 farm dweller households. Data on the current living conditions and livelihoods was collected on 15.3% of the farm dweller population in the area. The paper demonstrates that farm dwellers are a fragmented, agricultural precariat subject to push and pull drivers of mobility that leave them with a precarious hold on rural farm dwellings. The key provocation is that we need to be attentive to whether the hold farm dwellers have over land and livelihoods is slipping further as a result of instability in the agrarian economy? This instability arises from agriculture’s arguably maladaptive response to the intersection of structural agrarian change and climate risk in post-apartheid South Africa. While the outcomes will only be apparent in time, the risks are real, and the paper concludes with a call for agrarian policy pathways that are both more adaptive and achieve social justice objectives.

1. Introduction

What place is there for farm dwellers in South Africa’s changing agrarian and climate context? The uncertainty over this issue is what we intend to engage in this paper. Some things are more certain, however. Three key features of South Africa’s agrarian economy 24 years into democracy are the persistence of a racially skewed distribution and structure of land ownership with most rural people living on state land under traditional authorities and accessing land through (neo-) customary processes (Hornby et al., 2017 [1]); concentration, centralisation, and integration of agricultural capital creating a globally competitive but highly capital intensive and labour shedding agro-food regime (Greenberg, 2015 [2]); and, the ongoing evictions of farm dwellers from commercial farms despite tenure reform laws, with totals exceeding evictions from a decade prior to 1994 and greater than the number of beneficiaries of land reform policies (Wegerif et al., 2005 [3]).

The politics of land reform remain contested while consensus on agrarian solutions is elusive. AgriSA, the national agricultural union representing commercial farmers, claims that the government’s target to redistribute 30% of white owned farmland has been achieved (AgriSA, 2017 [4]). However, methodological critiques (Hall and Cousins 2017 [5]) show that the real figure is closer to 8% (Aliber and Cousins 2013 [6]) and growing populist demands for land expropriation without compensation indicate widespread discontent with the land ownership distribution. Debates on agrarian futures revolve around the possibility of expanding rural household use of small plots to generate food and income (Aliber and Cousins 2013, Hall, 2009a [6,7]), while others (Sender and Johnstone 2009, Hein, 2011 [8,9]) suggest that the dominance of large scale farmers and agro-food conglomerates (or ‘Big Food’) (Igumbor et al., 2012 [10]) eviscerate the space for small farm strategies. O’Laughlin et al. [11] argue that “Land reform can therefore be seen as simultaneously both central and marginal (or ‘necessary but not sufficient’) to meeting South Africa’s crisis of employment, livelihood and social reproduction …”

This poses serious challenges for South Africa’s attempt to use agrarian reform to confront rising unemployment, persistent structural inequality, and growing poverty and hunger1, particularly for farm dwellers, the focus of this paper. Moreover these challenges are exacerbated in the context of emerging climate change risks. Global warming is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest environmental, social, and economic threats to sustainable development in the world this century (Agrawala and Frankhauser 2008, Stern 2008, United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2014, Ziervogel and Taylor 2008, Anbumozhi 2009, Kaijage 2011, Turpie and Visser 2012 [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]). In South Africa, the mean annual temperatures have increased by at least 1.5 times the observed global average of 0.65 °C over the past five decades and extreme rainfall events have increased in frequency (Ziervogel 2014 [19]). Both the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and South Africa’s own localized and downscaled assessment models project warming of about 3–6 °C by 2081–2100 (IPCC 2014, Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT) 2004 [14,20]). Despite the parallels, there is a disconnect in the literature with agrarian political economists tending to neglect climate as a factor of change, while the climate change literature disregards how these changes will intersect with the social dynamics underlying agrarian change. Yet, climate change could deepen and exacerbate pre-existing historical and current vulnerabilities of the approximately 2 million (Stats SA 2011 [21]) already vulnerable farm dwellers across the country.

This paper thus investigates the degree to which farm dwellers, their land tenure and livelihoods are subject to a “double exposure” (O’Brien and Leichenko 2000 [22]); vulnerable to the impacts of post-apartheid agrarian dynamics and change while their land-based livelihoods are vulnerable to climate change as are the commercial farm enterprises on which their wage labour and residential rights depend. The study is innovative in providing extensive data on frequently neglected rural dwellers, namely those who live on commercial farms that they do not own, and in drawing attention to their double exposure to a combination of agrarian and climate changes, the livelihood vulnerabilities that are created, and the particular politics that this generates on farms.

The paper demonstrates that farm dwellers are a “fragmented” (Bernstein, 2010:110 [23]) agricultural “precariat” (Standing, 2011 [24]) that are subject to centrifugal (push) and centripetal (pull) drivers of mobility that leave them with a precarious hold on rural farm dwellings. The key provocation of this paper is that we need to be attentive to whether the hold farm dwellers have over land and livelihoods is slipping further as a result of instability in the agrarian economy2? This instability, we suggest, arises from agriculture’s arguably maladaptive response to the intersection of structural and climate change in post-apartheid South Africa. While outcomes will only be apparent in time, we suggest the risks are real, and the paper concludes with a call for more research, and for agrarian policy pathways that are both more adaptive and achieve social justice objectives.

2. Capital, Climate and the Agricultural Precariat

The contested discourse of a new geological era, in the form of the Anthropocene—in which anthropogenic climate change is acknowledged to have fundamentally altered our climate system (Clark 2015, Morton 2014 [27,28])—provides an entry point for a number of issues that re pertinent to this paper; namely the interconnections between climate, capital and socio-ecological change. Moore 2017 [29] argues that there is a fundamental Human/Nature dualism at the centre of the Anthropocene discourse, which “obscures our vistas of power, production and profit in the web of life”. Instead of the Anthropocene discourse, which begins with Nature as analytically distinct to a homogenous and abstracted notion of Society, Moore, amongst others (Klein 2014 [30]) proposes the Capitalocene as a way for understanding the conditions for co-production in the planetary ‘web of life’, and how capitalism has revolutionised the “co-production of historical natures” (ibid: 599).

Indirectly substantiating this argument, O’Brien and Leichenko 2000 [22] consider processes of globalisation together with climate change arguing that “on-going processes of economic globalization are modifying or exacerbating existing vulnerabilities to climate change” (ibid, 221).

Most directly, the connection between highly capitalised, commercial agriculture and climate change is one of cause and effect: on one extreme commercial agricultural systems are energy-intensive and fossil-fuel based, and thus contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Estimates posit that agriculture and the food system as a whole accounts for between 8.2% (Takle and Hofstrand 2008 [31]) to 29% (Vermeulin et al., 2012 [32]) of global greenhouse gas emissions, thus further accelerating climate change (Hewitson et al., 2005 [33]). Moreover, some scholars (Weiss 2013, Van Der Ploeg et al., 2015 McMichael and Schneider 2011 and Schneider and McMichael 2010 [34,35,36,37]) contend that the shift towards a highly capitalised, mono-culture form of agriculture has constituted a form of maladaptation to ongoing climate change and associated shifting agro-ecological conditions. Grain production (specifically maize in Southern Africa and rice in Asia) faces particular adaptation threats due to sensitivity to small temperature increases (IAASTD, 2009:287 [38]), with small farmers most at risk (ibid). Maladaptation, according to the IPCC (2014 [14]), is ‘an adaptation that does not succeed in reducing vulnerability but increases it instead’.3

Yet Moore’s argument is further nuanced regarding accumulation dynamics, where he situates the capitalist revolution in the co-production of historical natures in the four “cheaps” of Nature—labour4, food, energy, and raw materials—that have sustained capitalism’s expansion and that are now drawing to an end. The launch of the green revolution in the 1960s, along with the intensive investment that accompanied it, was based on the extensive farming of monocultures and supported by a boom in the agrochemical sector and fossil fuel based mechanization (Capra, 2015 [39]). While the new technologies supported an exponential growth in agricultural production and increased food supply for a growing world population (Bernstein 2010 [23]), the assumptions were that the climate would remain stable and both fossil fuels and water supply would always be abundant and affordable (Capra 2015 [39]). However, the mounting evidence of climate change and food price volatility (Holt-Giménez a & Altieri 2013, Van Der Ploeg 2013 [40,41]) have shown the limits of these assumptions. Commercial agriculture is now increasingly faced with prospects of peak fossil fuels, peak fertilizers (Pinock 2010 [42]), falling water tables in some regions, with risks of food shortages, increasing food prices, and increased social instability (Raleigh et al., 2015 [43]), as well as global political pressures to curb agriculture’s contributions to greenhouse gas emissions. The spatially uneven distribution of climate change effects (O’Brien and and Leichenko 2000 [22]) has already resulted in periodic declines in crops yields and failures in some regions.

Of interest with regards to ‘cheap’ labour in South Africa, the dynamics run somewhat contrary to Moore’s assertion of scarcity, with increasing precarity for an oversupplied labour base. O’Laughlin et al., 2013:6 [11]) argue that it was apparent in the 1970s “that the system of migrant labour [in South Africa] had eroded its own conditions of existence”. The subsistence ‘subsidy’ that household farming in the apartheid ‘Bantustans’ had provided to agricultural and mining wage labour had been undercut by overcrowding as a result of forced removals and consequent declining farm production. However, this particular contradiction created the basis for the subsequent emergence of ‘surplus labour’ as people continued to migrate out of rural areas and the need for labour in mining and manufacturing declined. As a result, “cheap labour was no longer scarce and securing it no longer required systematic state intervention” (ibid). Furthermore, the growing surplus of labour over the past 40 years have “narrowed the range of employment-based entitlements, cut flows of remittances between rural and urban areas, and heightened competition for jobs and access to services” (ibid).

The effect of this surplus labour boom alongside the capitalist restructuring of agrarian social relations have been far reaching for rural farm dwellers and labourers. Ewert and Du Toit 2005: [45] use the idea of a “double divide” to characterise the changes in the agrarian structure that have take place over the past four decades. On the side of capital are farmers “able to profit from the opportunities offered by international expansion and those who are not”; and, on the side of labour is a growing gap “between ‘core’ workers and those thrown out by casualization and externalization”. While there is no reference to what happens to the dynamics internal to the double divide in the context of climate change, an effect of the double divide has been the growth of a “rural lumpenproleteriat, often residing in rural, peri-urban or metropolitan shantytowns” (ibid: 317).

Perhaps more accurately, the position of farm dwellers in the face of these trajectories can be described as something of a rural agricultural precariat. Standing 2011 [24] argues that the fragmentation of the labour market accompanying globalisation has created a new social class of people who are ‘habituated’ to precariousness characterised as flexible, insecure and intermittent employment as well as “uncertain access to housing and public resources”. While the idea that the ‘precariat’ constitutes a specific social class has been thoroughly critiqued for disregarding the (geographically varied) logic of class domination under capitalism (see Breman 2013, Bernado 2016, Munk 2013 [46,47,48]), further theorisation has linked employment precariousness (or ”wageless existence” for Denning, 2010 [49]; ‘footloose labour’ for Breman, 1996 [50]) to eroded conditions of social reproduction (Hart 2014, Bernstein 2004: 205–6, Bernstein 2003: 210 [51,52,53]). Tania Li (2010: 67 [54]), in her essay ‘To Make Live or Let Die’, argues that the deepening condition of precariousness is the result of a new round of enclosures, leading to the dispossession of large numbers of rural people from land combined with “the low absorption of their labour, which is ‘surplus’ to the requirements of capital accumulation”. It is in this sense that we find the term ‘precariat’ a useful conceptual lens to engage with changing social relations on farms in the rural midlands of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province, to which we presently turn. Firstly, however, we set out the KZN context of capitalist agrarian transformation in South Africa over the past decades.

3. Study Method

The evidence is drawn from a 2017 survey that was undertaken by the Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA), a land rights NGO that works with farm dwellers in the Umgungundlovu District of the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province. The Umgungundlovu District, which is located in the midlands area of KwaZulu-Natal (the country’s second most densely populated province), is one of 11 municipal districts that are located on the east coast of South Africa, inland from the port city of Durban. The District has a population of just over a million inhabitants, 61% of whom are located in the Msunduzi Local Municipality in the vicinity of the city of Pietermaritzburg (Stats SA, 2017 [55]). The commercial farm areas are dominantly sugar, forestry and beef with some poultry and diary. The farm dweller population is estimated to be just under 41,000 people.

The survey was undertaken as part of AFRA’s Pathways Project, whose objective is to find pathways for farm dwellers out of poverty.5 The purpose of the survey was three-fold: firstly, to collect base-line data on farm dweller households in the district in order to update information on the living and livelihood conditions of farm dwellers across the district; secondly, to provide data that could be used in longitudinal studies to assess changes to the living and livelihood conditions of farm dwellers; and thirdly, to provide a GPS location of the interviewed farm dweller households and summary data on rights to land and services as a record of evidence to be used to adjudicate any arising future disputes over rights.

Surveys on farms in South Africa are not politically neutral processes of data collection. The research was planned to be undertaken together with land owners in a single municipal area, but after landowner structures subsequently withdrew their co-operation, AFRA changed the scope to a sample of farm dweller households across the District in order to ensure access to a representative sample. The access to farm dwellers then had to be negotiated through other structures, which included elected councilors, community development workers, and farm dweller structures. This may have created some bias in the sample in that the farms more likely to be known to these structures are those where farm dwellers have reported problems of some kind, but these problems also constitute the rationale for researching farm dwellers in the first place. A further dimension shaping the sample was that some land owners prevented the researchers from accessing farms and in one case threatened to bring trespassing charges.

The sampling method under these conditions was essentially opportunistic and the robustness of the data depended on the percentage of farm dweller households sampled.6 The survey was conducted with 843 farm dweller households, which collected data on 6478 individual men, women, and children, living on 83 farms, and thus comprises an estimated 15.8% of the farm dweller population in the District. Data was collected on both individuals7 and households8, and analysed accordingly. The instrument was piloted repeatedly and amendments to the instrument were made on the basis of research assistants’ experience of administering the survey.

The survey was loaded onto a tablet, and interviews were undertaken by six research assistants over a six month period, with a subsequent two months for checking and correcting errors.9 Data analysis was undertaken in excel and made available on a limited access website as information was being updated. Cross-tabulations were run across variables where possible relationships had been identified through literature or through focus sessions with farm dwellers and AFRA field staff. In terms of ethics, AFRA was concerned that the collected data not be used by landowners or government to further erode land and service rights of farm dwellers. The permission of respondents to be interviewed was thus obtained in every case, and the respondents assured that the data linked explicitly to their names would not be released without their consent.

4. Structural Change and Labour Vulnerability in South Africa’s Agrarian Economy

The structure of South Africa’s agricultural economy is the outcome of history, its persistent effects into the present, and of changes occuring in the democratic period (Ledger, 2016 [58]). Bernstein (1998: 1 [59]) states that “land and production, poverty and power, are key coordinates of the terrain of the agrarian question and of prospects of agrarian reform” in South Africa. These “coordinates” are often characterised as a dualism10, with poverty, overcrowding, and subsistence agriculture in the apartheid-constructed former ‘Bantustans’ existing alongside the vast, highly capitalised, mainly white-owned commercial farms. An often-neglected dualism is the persistence of “divisions and stark contrasts within commercial farms …[which] exemplify the twin processes of accumulation and underdevelopment, featuring extreme poverty (among farm workers and dwellers) in the midst of substantial agrarian wealth in large-scale capitalist agriculture” (Hall et al., 2013: 48 [60]).

Beyond its apartheid history, what accounts for these changes? Answers are complex, and include policy changes in the early 1990s resulting in de-regulation (Marais 2011: 124 [9]), the dismantling of apartheid agricultural marketing boards and monopolies and the withdrawal of government subsidies (Hall 2009 b [61]), and the reduction of tariffs on agricultural imports that exceeded with the requirements in 1994 of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) (Ledger 2016 [58]). Nicholson (2001 [62]) shows that tariffs on agricultural, forestry, and fishing imports were set at 41.2% but had been reduced to 2.2% by 1998. The changes meant that South African farmers were, over a very short period, expected to compete on global markets, and in this “moment of globalisation” (Bernstein 2003:203 [53]) were subjected to conditions of extreme competition and an “export or die” (Andrade 2017 [63]) dynamic. There was a need to adhere to and pay the costs for stringent quality requirements imposed by these markets (Reardon et al., 2003 [64]), with little support from the South African state and despite continued subsidies provided to farmers in Europe and the United States (Visser, 2016 [65]). These new conditions and disciplines have made it difficult for emerging small farmers to gain a secure foothold (Ledger 2016 [58]).

Capitalist agriculture’s response to the changes has varied. Sections of agrarian capital supported and lobbied for the changes in the early 1990s in order to open up their access to global markets (Bernstein 1996 [66]) resulting, amongst others, in expansions of sugar milling corporates and their commercial models into Africa (Dubb 2016 [67]) and forestry corporates into Europe and the United States. Others used the opportunities to assert local market dominance, with the rise in ‘Big Food’ dominating the food and beverage sectors (Igumbor et al, 2012 [10]), the emerging dominance of a small number of retailers and supermarkets (Reardon et al., 2003 [64]), the squeezing out of small growers from the agro-food system (Weatherspoon and Reardon 2003 [71], and increased expenditure of rural households on food purchases (D’Haese and Van Huylenbroeck 2005 [72]). However, many agro-corporates and commercial farmers have not survived the new ‘disciplines’ of competition and have gone out of business (Visser 2016 [65]), as is evidenced in the declining number of farming units; in KZN the number of commercial farm units declined rapidly from 6080 in 1993 to 3574 units in 2007. Accompanying this decline is the growth in the mean size of farms from 668 ha in 2003 to 808 ha in 2006 (Stats SA 2013: 6 [56]).

Genis (2015 [73]) summarises responses to changes in conditions for agricultural production as follows. Firstly, an expansion and consolidation of production and landholdings, which resulted in increased concentration in agriculture. Secondly a large degree of centralisation, with vertical integration into up and downstream value chains. This is less apparent at farm level and most apparent in the agrochemical and seed sector (e.g., Monsanto, Bayer) although the concentration at farm level is probably a response to centralisation beyond the farm-gate. Thirdly, increased labour productivity, through the systematic application of labour technologies in work processes and mechanization. These changes have enabled shifts to smaller, more skilled farm labour, with low skill or seasonal work being undertaken by contracted labour. This reorganisation of labour has particular pertinence for this paper because it also threatens to snap the connection between farm labour and access to land (Hall et al., 2013 [60]). Finally, increased production efficiency through the use of high-yielding plant varieties and production practices, e.g., conservation agriculture, moisture conservation, and pruning practices.

KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal’s agricultural structure reflects key features of the national structures, specifically, racially skewed land ownership, a decline in contribution to GDP, and a decline in the number of farming units with an associated increase in the size of farms; together with a restructuring of labour, which has included an overall decline in jobs and a shift to contract and seasonal work.

In terms of its contemporary land dispensation and agrarian patterns, the KwaZulu-Natal Agricultural Union (KwaNalu) claims that 46.29% of land in the province is black owned, while only 15.6% is white owned (with about 35.8% of the province’s land ownership unknown) (De Lange 2017; Groenewald 2015 [74,75]). These statistics include nearly half of the province’s land that is owned by the Ingonyama Trust Board, which is a public entity. To describe the tenure in these areas as black ownership is misleading and inaccurate. By contrast, the audit of state owned land undertaken by the Department of Rural Development and Land reform (2013: 9 [76]) suggests that 50% of the province is state owned, while 46% is privately owned, with only 4% unaccounted for. The report does not provide a racial or urban/rural breakdown but does indicate a shift from individual private ownership to corporate ownership of rural land, and reflects some ownership changes as a result of transfer through land reform. However, accurate data on the exact racial and class composition of land ownership in the province and the mechanisms accounting for changes do not exist.

The contribution of agriculture to KZN’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has declined from 4.4% in 2004 to 2.1% in 2014 (TIPS 2016: 3 [77]), though with a slight increase to 2.3% by 2017 (TIPS 2017 [78]). Despite this decline, agriculture is nevertheless more important to the provincial economy than agriculture generally is to the national GDP. Employment in agriculture in the province has fluctuated: 150,000 jobs in 2008, down to a 100,000 in 2011, and up to 148,000 in 2015 (ibid).

The dominant agricultural commodities in KwaZulu-Natal are forestry, sugar, poultry and beef production. Forestry uses 5.5% of KZN’s total land (exceeded only by Mpumalanga Province at 6.3%). Although a relatively low user relative to 12.7% used for arable production, 58.3% for grazing, and 15.1% used for nature conservation (Godsmark 2013 [79]), forestry in KwaZulu-Natal makes up a significant proportion of the national forestry hectorage, expanding from 36.8% in 1979/80 to 39.9% in 2015/6. While forestry’s contribution to national agricultural GDP has risen from about 4 to 10% (although declining from just above to below 1% of national GDP), its contribution to manufacturing GDP through processing has declined from approximately 6 to 5%. This drop has been associated with the halving of employment in the KZN wood and paper industry from approximately 34,000 jobs to 15,000 between 2010 and 2015, the most rapid decline in provincial manufacturing industries over this period (TIPS 2016: 4 [77]). The drop-off in manufacturing employment could be explained by the diversification and globalisation strategies of the SAPPI and MONDI forestry corporates, while Mondi has also shifted to a longer term strategy of leasing rather than owning land subject to land reform (SAPPI 2016 [80]).

Sugar is the provinces second most important agricultural revenue earner after forestry, generating R2,3 bln in 2007, followed by broilers (R1,7 bln) and beef farming (R1,4 bln) (Stats SA 2007: 11 [81]). KwaZulu-Natal accounts for 90% of the country’s sugar production (Thornhill et al., 2009 [82]). The Department of Agriculture, Forest and Fisheries (DAFF) (2016 [83]) reports that 318,865 ha (4.8%) of agricultural land in the province is under sugarcane plantations, a decrease of about 24% from the 2006/07 season, which stood at 419,465 ha (6.3%). Most sugar in the province is grown under dryland conditions (SASA 2017 [84]), and hence is vulnerable to climate variability. The sector experienced a decline in employment that was associated with a decline in output per hectare over the last two decades due to a combination of factors, including rising input prices, volatile global sugar prices, drought, and its impact on yields and quality of production, the withdrawal of state subsidies since the 1990s (EDTEA 2017 [85]), the perceived risks of land reform (Cronje 2015 [86]) and rising labour costs (Visser 2016 [65]).

The poultry industry (which has a high concentration of broiler chicken production in the Umgungundlovu District between Cato Ridge and Pietermaritzburg) took a large knock after a trade dispute saw European goods flood the market (Meyer and Davids 2017 [87]). As the largest agricultural sub-sector in the country, poultry contributes 16.5% of the gross value of agricultural production, and is the cheapest and most consumed animal protein source (DAFF, 2016 [83]; Davids and Meyer 2017 [88]), whereas beef contributed 11.9% and sugar 3.2% of the total value of agricultural revenue nationally in 2015. KwaZulu-Natal has the highest percentage of agricultural households that were engaged in poultry production (27.5%)11 and vegetable production (30.3%), while the percentage of agricultural households that were engaged in cattle production (24.5%) is second to the Eastern Cape (Stats SA, 2013 [56]).

In terms of climate risk, Thornhill et al., (2009 [82]) note that KwaZulu-Natal has been subject to extreme weather episodes at regular intervals over the last 100 to 150 years, and while there are data gaps that make it difficult to identify trends with surety, these events are likely a part of a continuum of events whose frequency and severity will increase in the future. The impacts of these events will be made more severe by the degradation of natural abatement systems, such as floodplains, wetlands, forested valleys, and coastal dunes. Discussion of further climate impacts are the subject for the penultimate section, and we now proceed to discuss the survey data on farm dwellers in KZN.

5. Farm Dwellers in KZN as a Rural Precariat

According to the 2011 Census [21], 3.7% of South Africa’s population lives on commercial farms that they do not own, and yet little is known about the living conditions of farm dwellers. Farm dwellers are a distinct category of rural dweller, and while there are overlaps with farm workers, to collapse them into a single sociological category blurs important differences between them. Farm dwellers in this study, following AFRA’s definition (2017 [89]), include four categories: waged farm workers who have long histories of living on the farm together with their families; waged farm workers who have recently come to live on the farm with their families and have no homes elsewhere; migrant farm workers who have homes elsewhere (often in other countries) but visit them infrequently; and finally, families with nobody working on the farm, but who have lived many generations on the farm and have no homes elsewhere.12

The 2017 AFRA survey of 838 farm dweller households13 living on 83 farms across the Umgungundlovu District in KwaZulu-Natal found that the mean size of farm dweller households is 7.2 members, with 55.8% with six or more members, a significantly higher number than the 3.5 members per household national mean (Wittenberg et al, 2017: 1299 [90]). 35% of household members are younger than 18 years, 52.1% are female and the remainder male, with slightly more men between the ages of 18–35 (50.9%) than women of the same age.

Farm dwellers secure incomes from multiple sources, including wage work on farms and off farms, social grants, remittances and own enterprises. However, rising unemployment and labour casualisation on farms (identified above) combined with declining work opportunities in rural and urban secondary and tertiary sectors, declining access to land for farming and high numbers without access to social grants means that farm dwellers, and particularly young men, struggle to secure the conditions for their social reproduction. The combination of these factors create the conditions for the identified politics. Drawing from the data and supporting literature, the following sub-sections cover the precarity, mobility, and politics of holding on related to farm dwellers.

5.1. Precarity

Two-thirds of farm dwellers (66.5%) over the age of 18 have no income at all. This means that they are unemployed, receive no social grants, and are involved in no enterprises or activities that generate income. Of those farm dweller households in our sample that do have an income from work, social grants or own enterprises or combinations thereof, there are significant differences in mean amounts, with a minimum of R014, a maximum of R95,840, the mean in the first quartile R2600, in the second quartile R4000, and in the third quartile R6600. As household sizes average 7.2 members, this means that members of households in the first quartile have a mean allocation of R361 per member per month, those in the second quartile a mean allocation of R555 per member per month and those in the third quartile R917 per member per month.

Our data thus suggests that farm dwellers may be worse off than previously indicated.15 Furthermore, 75% of members in farm dweller households in our sample receive less than the upper-bound poverty line (of R992 per person per month) in 2015 prices (Stats SA, 2017 [55]). Stats SA (2017) reports that 55.5% of South Africans were poor in 2015, and that this rising poverty is concentrated among children, black Africans, females, people living in the Eastern Cape and Limpopo, and those with low educational levels. Our data shows that, by Stats SA’s definition, farm dwellers are one of the poorest, albeit socially differentiated, social categories in the country, and that their poverty levels and the inequalities may be obscured in national data sets. The reason for this possibly lies in nuances revealed by distinctions in the data between individual and household incomes, primary income sources and combined income sources and temporary, seasonal, and contract employment along with unemployment.

Farm labour (combining permanent, temporary, and seasonal labour)16 constitutes half (49.9%) of the primary income sources of individual farm dwellers that have an income when those who have no income are excluded from the analysis. Wage labour is thus a very important source of income. This is not significantly different from 51.1% of permanent farm labour reported in Visser and Ferrer (2015: ii). However, the figure drops to 38.9% when labour (of unspecified duration) only on the farm on which the farm dweller is resident is taken into account, as opposed to work on another farm in the area. Furthermore, of those individual farm dwellers whose primary17 income is from farm labour, our data shows 79.5% are permanent workers, followed by temporary or contract workers (18.9%) with very few people stating seasonal work (1.6%) as their primary income source18. Notwithstanding methodological and analytical differences in the studies, this is significantly less than the work of limited or unspecified duration of 48.9%, as reported by Visser and Ferrer (2015:21 [57]) and Hall et al., (2013:53 [60]), and when factoring in those farm dwellers over the age of 18 who have no incomes at all, then full-time permanent employment on the farm on which they reside is the primary income source for just over 10% of farm dwellers.

Relatedly, incomes and their differentials also appear to have a bearing on how farm dwellers view their relationship with farmers (something that has a bearing on the ‘politics of holding on’ section to follow). Where the distribution of the total primary income of households is relatively equal, households are more likely to rank the relationship with the farmer as good (see Table 1). Indeed, even where a high percentage of household incomes fall into the fourth quartile of highest incomes, this distribution does not improve the ranking of relationship with the farmer.

Table 1.

Household Primary Income Distribution V Relationship to Farmer.

The worst relationship ranking is where most of the households fall into the first income quartile, and this indicates a significant, simmering politics of discontent surrounding farm dweller precariousness and fragmentation.

Other primary sources of income for individual farm dwellers (excluding those in the sample who have no income) are child grants and government old age pensions (15.9% and 13.4% respectively) and off farm income (13.8%). While primary income sources reveal an important component of farm dweller incomes, the diversification and combination of incomes shows the increasing importance of multiple income sources to farm dweller livelihood strategies (see also Cousins (2013 [94]). More than half of farm dweller households (60.6%) have more than one income source, in a range of 0 to 12, while only 38.1% of households have a single income. The most frequently stated secondary income source is child grants (15.3%), and the most frequent combination is mainly permanent full-time farm work as the primary income supported by child grants. Reversals are also apparent, for example, government old age pensions the primary income source supported by part-time work on the farm. Other secondary income sources include other social grants (child foster grants, disability grants), own businesses, second part-time jobs in addition to a primary job, and remittances. While work-social grant livelihood combinations may avoid the precariousness of intermittent contracted work, very few farm dwellers secure this combination of livelihood strategy or the alternative income source from contracted and seasonal work opportunities19.

We thus suggest that declining permanent employment (in agriculture and industry) and modes of labour casualisation of farm labour that exclude farm dwellers, together with uneven access to social grants, small (agricultural and other) businesses are resulting in social differentiation among farm dwellers with associated fragmentation. Farm dwellers are, in other words, a poor but diversified and socially differentiated precariat, whose best chance of survival is multiple, combined incomes strategies, alongside mobilities, which the next sub-section indicates.

5.2. Mobility

The social dynamics underlying mobility can be analysed in terms of centrifugal or push factors (moving from a central zone to another periphery, i.e., from the farm dwelling to town) and the converse centripetal forces (attractive qualities operating at destination peripheries that attract individuals to them (Colby, 1933 [95]) or pull factors back to the farms. The data indicates that farm dweller mobility falls into three distinct types: eviction, constructive eviction, and voluntary migration. In the latter case, migration involves both movements off the farm, as well as movements back to the farm.

Regarding prospective evictions, 7.1% of individual farm dwellers20 have had permission to reside on the farm withdrawn, with 76% of these taking place after 2005. This is the first step hat a farmer is obliged to take in order to secure an explicit, or legal eviction.21 The reasons given by land owners for withdrawing permission vary (as Table 2 below shows), although in most cases farm dwellers said farmers simply said farm dwellers should make their homes somewhere else.

Table 2.

Reasons for farmer withdrawing permission vs. Age category.

Despite having their permission to be on the farm withdrawn, not all of the affected farm dwellers have moved off the farm. As Table 3 below shows, of those whose permission to be on the farm has been withdrawn over half (53%) stay home most nights. Perhaps more striking than the impending potential evictions is that of the many individuals who said that they have the farmer’s permission to be on the farm, nearly a third (31%) do not stay at home most nights, suggesting that more farm dwellers are leaving farms, at least temporarily, for reasons other than an explicit eviction.

Table 3.

Permission to stay on the farm vs Stays home most nights.

Evictions can also take a ‘constructive’ form. Legal, explicit eviction procedures, which require a court order, alternative accommodation and reporting to the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform and the local municipality, can be onerous and expensive for the landowner (AFRA, 2017 [89]). As a result, some farmers pressure farm dwellers to vacate on-farm residences. Constructive evictions thus refer to processes whereby the landowner puts pressure on the farm dweller with the intention of pushing him or her to decide to abandon the property. They can take many forms that are designed to compel farm dwellers to ‘decide’ to leave the farm, including acts of omission (withdrawing access to basic needs such as water or energy resources), or more explicit acts of commission (fencing in the household and depriving children of access to roads needed to get to schools (Reilly, 2014 [96]), or refusing occupiers permission to renovate their houses, even at their own cost and in an effort to create habitable living environments for their families that secure human dignity22).

Omission of services is a common impetus for constructive evictions, and this is reflected in the relationship between farmers and farm dwellers. Table 4 shows that the higher the number of households that have access to a bundle of goods (including access to electricity, water and toilet, the presence of family graves on the farm, and the right to have visitors), the higher the probability that farm dwellers will rank their relationship with the farmer as good. Similarly, if a higher number of farm dwellers do not have access to the bundle of goods, then the relationship is ranked as poor. We assume that a poor relationships with farmers are more likely to result in conditions giving rise to constructive evictions, than where relationships are good. However, the relationship to farmer trends suggested by access to a bundle of services, while present, is not strong.23

Table 4.

Relationship to farmer V Access to bundle of goods.

Evictions, constructive or explicit, are not the only reason farm dwellers leave farms, as centrifugal forces are at play. Of the 31% of adult farm dwellers who have the landowner’s permission to live on the farm but do not stay on the farm most nights, nearly half (41.6%) left because they have found work elsewhere, followed by a third (32.1%) who went to live with relatives living elsewhere, sometimes in order to provide support to those relatives. It is also possible that while some respondents stated that various household members had gone to live with other relatives, they had in fact been told by the farmer that they should leave the farm.24 As Table 5 below shows, there is a gendered dimension to this centrifugal mobility, with more men (61.6%) than women (38.8%) leaving for reasons of finding work elsewhere, while many more women left the farm for reasons of marriage (86.3% compared to 13.7% of men) or to live with families elsewhere (57.4% of women compared with 48.6% of men). Finding work elsewhere was the most frequently given reason given by men for leaving the farm (61.6%), whereas going to live with relatives was the most frequent reason women had for leaving the farm (32.1%).

Table 5.

Gender of farm dwellers with permission to be on the farm who have left.

There is also a significant gender-generational nexus to those that are leaving farms for the purpose of working elsewhere. More than half (58%) are young men that are below the age of 35. This is probably due to a combination of factors, including that young adult men do not have social grants to reduce their income vulnerability and that women are more likely than men to be expected to undertake family duties where there is a need for support and care.

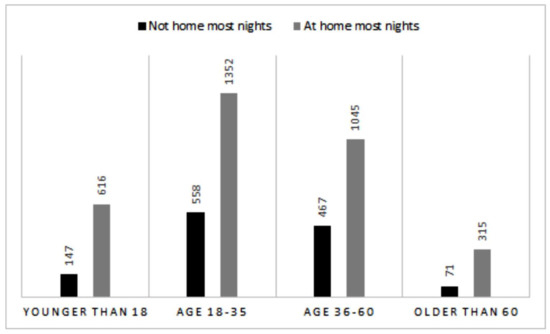

Centripetal forces also operate to draw farm dwellers back to the farm in migration patterns that are often described as circulatory. A perhaps surprising feature of the data is the high preponderance of young adults who are on the farm. As Figure 1 below shows, 71% of young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 stay at home most nights. Although most of the people leaving farms for work elsewhere are young men in this age group, the size of this age group on farms together with the high proportion who have no income from any source suggests that this is the most vulnerable sub-group in the agricultural precariat, and that residence on farms is the best of their a very limited range of options for living.

Figure 1.

Age Category of Adult Farm Dwellers Home Most Nights.

Anecdotal evidence from AFRA (Sithole, 2017 [97]) suggests that this growing population of younger adults, many of whom are better educated than their parents and who have a better understanding of their legal rights, is a source of friction on farms. Whereas, older generations tend to adhere to the farm rules, younger adults are more willing to confront farmers around what they view as unreasonable actions. In a particular case in the Umgungundlovu District, the farmer locked the gate and prevented a farm dweller household from admitting visitors who had arrived by car to attend a ceremonial family function. The younger adults eventually cut the lock, which resulted in a confrontation with the farmer, who had a firearm, and his wife. The conflict was recorded on phone video and sent to AFRA. Strikingly, the farmer asserted his right to lock the gate on the basis that “This farm is mine. I have a title deed”, to which the young farm dwellers in the dispute responded: “This is our home. This is where we live”. We turn now to consider further these centripetal forces of that pull farm dweller back to homes on farms, or the politics of holding on to the land.

5.3. The Politics of Holding on to the Land

A significant number of households, and in particular, young adult members of households, remain on farms, despite difficult and worsening living conditions, which contradicts the processes of “rural hollowing” (Liu et al., 2010 [98]) that an over-simplified analysis of the push-pull migratory trends would suggest. Farms are neighborhoods that constitute the foundations of well-being and identity of those who grow up on them (AFRA, 2005 [99]). Together with deep connections to graves and the recreation of these links through ongoing burial practices, “[1] and ties people to their histories” (Greenberg, 2015: 975 [2]), and this is an important centripetal force to take note of. Our data shows that farm dwellers assert ‘home’ as a place that belongs to them, based on histories to specific land that are re-enacted through ceremonies in the present, along with entitled remuneration for a life of labour.

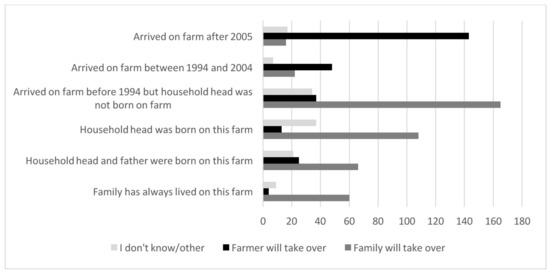

Dynamics of belonging are multi-faceted. Despite restricted financial resources, Mosoetsa (2011 [100]), in a study of home, shows that familial solidarity is not compromised in settlements on the periphery of cities in KwaZulu-Natal, and is expressed as “eating from one pot”. The reference to food as an anchor for the farm dweller family is also supported by the data, which indicates that 69% of households cultivate gardens on the farm and 44% own some livestock.25 History and length of occupation on the farm also play a role, as Figure 2 below shows. Nearly 70% of households (69.6%) arrived on the farm where they live before 1994, with 59% of those stating that the family had either always lived on the farm, or that one or both of their father and grandfather had been born on the farm. There is a key correspondence between when a household came to live on a farm and who they believe will take over the home on the death of the household head.

Figure 2.

What will happen to the house V When the family came to this farm.

The majority of respondents who came to live on the farm before 1994 said family would take over the house on the death of the head of house, whereas most of the respondents who came to live on the farm after 1994 stated that the farmer would take over the house. The reasons given by those who say a family member will take over the house include that they have always lived in the house and that they have no house elsewhere. A life of labour without adequate remuneration was also a justification. As one respondent stated: “My husband worked on this farm all his life and when he died, there was no pension. So I took this house to be his pension”.

There are ties between family and home in the data. 82.2% of farm dwellers who live in single room houses believe that the farmer will take over the house, whereas 78.7% of those who live in houses with five rooms or more said that family would take over the house, with only 0.06% stating that the farmer would take over. This corresponds with the presence of family on the farm as single-room quarters invariably (77%) have two or fewer occupants in them, whereas 87% of houses with more than five rooms are occupied by households with six or more family members. Households that have lived on the farm since before 1994 thus tend to be bigger and have more rooms, suggesting that these are homes for families.

While length of residence and presence of family is important to a notion of home, belonging is forged through keeping the link between identity and place alive in the present. This can be seen in the data on graves. Just over half of farm dweller households (422) have graves on the farm where they live. Hornby (2015 [101]) shows that ceremonial practices on farms in KwaZulu-Natal around the deceased are drawn-out, extended affairs that are located in specific homestead spaces and involve animal slaughter, communication with ancestors, and participation of extended family and community. The entanglement of graves, land, family, and community possibly explains why burials hold such potential for conflict between farmers and farm dwellers. Of the 99 households that are no longer allowed to bury on the farm, 46.6% judged their relationship with the farmer as ‘poor’ and only 6% said they had a ‘good’ relationship (60% of households that assessed their relationship with the farmer as being ‘poor’ have graves on the farm). This suggests not so much a process of constructive eviction as a process of constricting the space and normative activities that underpin ‘home’ for farm dwellers. This constriction of home-life could result in farm dwellers either abandoning homes on farms or defending homes on farms in order to secure the ceremonial and other social reproductive activities necessary for making homes.

Tying this together with unemployment figures and the on-farm household demographics that are shown above, the conclusion is that a large number of residences on farms are not housing for farm workers, but homes for families who have lived on the farm for 24 years and longer. These individuals expect that their homes will remain theirs into the future, and who continue to construct ‘home’ through ceremonial activities such as burials. However, this conclusion is contrary both to farm tenure legislation as well as the conclusions drawn by Visser and Ferrer (2015 [57]).26 While we do not dispute Visser and Ferrer’s conclusion that that “[e]xtending on-farm tenure security and protection from eviction is no longer the single, biggest need of farm workers” (ibid: v1) and that farm workers are an increasingly diverse group with a range of livelihood and tenure needs, our argument is that the farm is nevertheless “home” for a significant proportion of rural dwellers, many of whom do not secure their primary income from farm work.

We thus propose that farm dwellers are asserting a politics of home, of belonging to the land, as a counter response to what Barchiesi (2011 [102]) argues is the disciplining effects of the normative nexus of employment and citizenship that underpins South Africa’s “precarious liberation”. Unable to secure regular or ‘decent’ employment in the ‘new’ South Africa, some farm dwellers hang on to ‘home’ as a silent expression of a ‘subaltern politics’ (Spivak 1998 [103]). This politics arises from national and global drivers of agrarian change, but it also stands in tension to them.27 Moreover this subaltern politics constitutes the social force, together with increasingly constrained livelihood options, which could potentially activate a local politics that focuses on farm dweller precarity. With an understanding of structural changes in the agrarian sector and their relation to farm dweller’s distributed precarity and ‘holding on’ to land, we turn to consider the second component of the ‘double burden’ related to climate change risks and their implications for farm dwellers.

6. A Slipping Hold? The Risk of a Double Exposure for Farm Dwellers

Climatic changes that were observed in the province over the past 50 years include general warming (Hewitson et al. 2005; Schulze 2005, CSAG 2017 [33,104,105]), with weather stations along the coast reporting temperature increases of over 2 °C/century, more than twice the global rate of temperature increase (CSAG 2017 [105]). Hewitson et al., 2005, amongst other climate change studies (including Schulze 2005 [104]; CSAG 2017 [105]) identify the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands as one of three climate change hotspots in South Africa. This is because the warming already observed and the projected changes in climate have expected impacts on people, ecosystems and economies.

The important derived trends projected into the future (CSAG 2017, Zierwogel 2014 [105,19]) for the purposes of this article are: firstly, an increase in the annual maximum mean temperatures, particularly over the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands and the north-eastern parts of the province; secondly, an increase in heat units in the summer months across the province; thirdly, an increase in heat units in the winter months along the coast and inland to the Pietermaritzburg area, and finally, an increase in the annual means of minimum temperatures. The projected result of warming is changes in weather patterns with expected increases and variability in the amounts of precipitation coupled with changes in seasonality. These are likely to be accompanied by a corresponding increase in the intensity of extreme events such as floods, tropical cyclones, storm surges, heat waves and droughts. While statistically there exists no clear evidence of substantial changes in annual precipitation totals, seasonal total rainfall or daily rainfall extremes there is consensus that there is a general wetting trend over KZN, a phenomenon supported by modelling data in the 2017 draft of the Third National Communication Report to the United Nations Framework. Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The localized analysis of the extended Long Term Adaptation Scenarios (LTAS) data set for 1960–2015 indicates significant positive trends in annual rainfall in the south of KZN and negative trends in the north (CSAG, 2017 [105]).

With these changes in mind, O’Brien’s notion of double exposure is useful in approaching both the risk that farm dwellers will be affected by climate change at the household level at the same time as they are affected by a changing agrarian political economy, and that climate change and agrarian change may interact to amplify farm dweller vulnerability. According to McDowell et al., (2010 [106]), there are a variety of ways to understand and apply the concept of vulnerability, from a principally biophysical focus on climatic exposures to the concept of “social vulnerability” that exists, regardless of climatic conditions (Adger and Kelly 1999 [107], Kelly and Adger 2000 [108]). Erratic rainfall constitutes a significant biophysical risk to food security for those approximately 69% of farm dwellers in the sample supplementing their diets with home gardens. There are likely to be increased public health risks for those approximately 30% of residents with poor service access—especially to water borne diseases when faced with poor sanitation and water sources. Vulnerability studies assessing the level of risk should an extreme weather event occur indicate that KwaZulu-Natal has the highest human vulnerability to climatic events (Jansen Van Vuuren cited in Thornhill et al, 2009: 51 [82]). The province’s high level of human-climate vulnerability is closely associated with the high poverty levels and population densities coupled by high levels of land degradation (ibid).

While taking full cognizance of the importance of considering biophysical exposures, including extremes, such as flooding and drought, scholars (Adger and Kelly 1999 [107] Kelly and Adger 2000 [108] and Turner et al., 2003 [109]) posit that a focus solely on external stressors is insufficient in explaining how a population is exposed, its sensitivity, and its adaptive capacity (Fussel and Klein 2006 [110]). Low level social and economic conditions of a population, such as the precariat within the farm dweller sample, render it vulnerable, even in the absence of actual climatic events. In fact, McDowell et al., (2010 [106]) go as far as to say that the ability of a population to deal with biophysical exposures is a function of its social vulnerability. The sample can be interpreted as fitting with her framework of social determinants of individual vulnerability. These include low social status, lack of access to resources such as land (with farm dwellers lowest on the priority list for land restitution and redistribution (Hall et al., 2013 [60]), and a lack of diversity of income sources (high levels of no income combined with dependency on farm wage income and child grants). A lack of stable off-farm income for young adults in cities in a context of high unemployment also limit alternative—or multiple—livelihood strategies. Therefore, the on-going precarity of farm dweller livelihoods is the foundation for future climatic shocks because it increases their sensitivity to climate events and lowers their adaptive capacity.

A second set of dynamics relates to the implications for farm dwellers of climate change impacts at farm or regional/national scales, as well as those implications of mitigation or adaptation strategies on the part of farmers and government. The awareness and evidence base of these factors is nascent. Officially, however, the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEA, 2013 [111]) has identified agriculture as a sector highly vulnerable to climate change, and expects to see a reduction of 3.5% to 4.3%, respectively, in total average maize and wheat yields for the median impact scenario by 2050, with impacts on food production, agricultural livelihoods, and food security of a magnitude to be of national policy concern (DEA, 2013 [111]). Studies that were conducted by Turpie and Visser (2013 [65]) project costs to farmers of climate change to be R694 billion rand by 2080 (although KwaZulu-Natal is less severe than other provinces). This is likely to exacerbate the winners and drop-outs from commercial agriculture that were identified by Ewert and Du Toit (2007 [45]) above, entrenching and deepening farmers’ responses identified by Genis (2015 [73]), including labour shedding. The climate trends highlighted above, and in particular recent extreme weather events such as drought and floods, have already started having a bearing on the day-to-day decision-making processes of farmers. Hewitson et al. (2005 [33]) and Schulze (2005 [104]) suggest that these events are affecting farmers’ selection of cultivars, irrigation regimes, fertilizer, and pesticide applications, as well as number of farm employees, although Genis (2015 [73]) attributes these decisions to increased competition. An incidence of the knock on effects for the employment in KZN of labour reductions was evident in the sugar cane industry, where, largely in response to the 2016/17 drought, saw a decline of 14.1% in total number of workers on cane farms as compared with the previous year (Canegrowers 2017: 20 [84]).28

Such impacts beg the question of what is to be done. Mitigation strategies that were identified by DEA include building more sustainable production, enabling farmers to access more formal markets and finance, and incentivising carbon sequestration and climate smart agriculture (DEA, 2013 [111]).29 While the adoption of ‘biological’ farming practices (such as drip irrigation and zero till cultivation) are championed and have their place, purely technological approaches lack analytical integration of how vulnerability is either mitigated or exacerbated by the structural changes of the past 35 years, which largely entailed consolidation and expansion. Expansion of production can be a climate-mitigating strategy depending on the commodity produced.30 For example, goats in bush encroached communal areas may serve to control bush encroachment where it is beginning to displace grasslands (Alcock 2017 [112]). However, the expansion of plantations—for example, sugar and timber—is also likely to put pressure on diminishing ground water resources and increase crop yield vulnerability to intermittent drought, increased temperatures, and climate change induced crop diseases. In parts of the Umgungundlovu District, the plantation expansions of the global corporate, Mondi, have brought it into conflict with farm dwellers that are resident on the land it leases around eviction threats, diminished access to services, land for small farm production (Ziqubu 2017 [113]), and reduced opportunities for waged employment and contracting (Khosa 2000 [93]).

In relation to this, climate justice, food and agroecology activists (amongst others, Holt-Giménez and Altieri (2013 [40]) and Van Der Ploeg et al., 2015 [35]) argue that the expansion of land-holdings in response to competition (CF Genis 2015 [73]) and the increase of monoculture plantations in agriculture, create food security and climate related risks, and constrain adaptive responses to technological innovation and bioengineering. Their contention, fitting with O’Brien and Leichenko (2000 [22]), is that the social impacts of environmental distress are unevenly distributed across space and social groups, and that, in line with McDowell et al., 2010 [106], such strategies are in themselves maladaptive as they increase the vulnerability of other systems, sectors, or social groups (McDowell et al., 2010 [106]).

Such perspectives emphasise the need for a politics that enhances food and livelihood security at the household level for farm dwellers. Yet, the current land reform dispensation and agrarian trajectory that benefits elites rather than the rural poor (Hall and Kepe 2017 [116]) seems to preclude this eventuality. In this context, the land question remains a central and politically contested issue, and in particular, whether there is place for farm dwellers to own commercial farms? The shift in redistribution policy focus away from poor people who need land for multiple purposes, together with the government’s failure to develop a comprehensive tenure reform policy (Hornby et al., 2017 [1]), has meant that farm dwellers are no longer a policy priority for commercial farmland acquisition. Indeed, their tenure appears to have become more insecure with an escalation of evictions during post-Apartheid South Africa (Mntungwa 2014 [117]; Wegerif et al., 2010 [3]).

7. Conclusions

This paper set out that intersections between climate change risk, capital, and precarity are playing out at a farm-dweller household level in Kwazulu-Natal. Initially, we set out how structural change in the agricultural sector has created a diversified agricultural precariat. Farm dwellers are primarily a group of wageless, income-less adults, whose lives are precarious in that high levels of unemployment co-exist with declining permanent farm work and extremely limited and intermittent seasonal and contract work. Furthermore, farm dwellers are evidence of labour fragmentation, in that those who do have incomes secure them from multiple sources in a variety of combinations, with signs of emerging social differentiation being indicated in uneven distributions of income at both individual and household levels. Income precariousness is compounded by insecure tenure in the form of explicit and constructive evictions. This results in often circular migration to towns, where an absence of employment opportunities pushes people back home and generates a politics of holding on to home on the farms. Here, the concept of land as lived home space occupied by farm dwellers co-exists with the farm as landed property that is owned by the farmer. We see this as the expression of a subaltern politics that constitutes part of the social forces that activate ‘land’ as a politics of place and home and not simply as a site of production.

While in the main we demonstrate, based on our study sample, that this hold is tenuous, an additional concern in the context of this special issue is whether climate change exacerbates or the further causes the hold to slip? While there is as yet little evidence in the literature for claiming climate change impacts on agriculture in KZN or farm labour, and given that attribution is difficult in complex agrarian contexts, we suggest that the need to take into account climate related risks to an already precarious population is compelling. Here, we attempted to substantiate that the risk of a double burden for a rural farm dweller precariat is substantial. The structural trends in post-apartheid South Africa, which is characterised by a concentration on the part of capitalist agriculture, and a land reform dispensation that does not take into account farm dwellers, might be construed to constrain responses to climate change that could mitigate farm dweller vulnerability.

In contrast to these risks and vulnerabilities, we advocate an enabling politics and an agrarian plan that explicitly aims to mitigate this precarity and vulnerability, and beyond to create positive trajectories for change. Li (2015: 80 [54]) hints at this kind of progressive biopolitics, envisioning that “In a democratic system, and within the container of the nation state, tensions between productivity and protection may be worked out by means of the ballot and are embedded in laws that define entitlements and—just as important—a sense of entitlement that is not easy to eradicate”. Agrarian reform that puts farm dwellers at its centre is precisely such a legal entitlement arising from within the democratic system and that ‘works out’ some of the tensions between productivity and protection. Ferguson (2015 [118]) agrees that land reform is important for this reason. South Africa’s property clause in the Constitution gives effect to this. The Constitution protects rights to property. This is often interpreted as protection of rights to ownership, whereas land reform laws (especially ESTA and the labour tenants legislation) make clear that rights of occupation are a form of statutory property right. A transfer of such farm dweller rights to land could be undertaken with compensation only for the difference between the full bundle of ownership rights and these rights of occupation. Equal land distribution has a potential to provide vulnerable communities a platform to actively exercise their agro-economic activities. Therefore, secure land rights in conjunction with micro-scale farmer supporter, has the potential to bring about greater justice and equity (Greenberg, 2015 [2]), and, we argue, greater livelihood resilience.

In concert with Ewert and Du Toit (2005 [45]), we argue that a broader approach to pro-poor policies and citizen empowerment is necessary to address the problems on farms. The question is whether the social conditions identified, in particular the fragmentation of farm dwellers as a result of diversified income and income strategies, create the conditions for a politics to pursue the interests of farm dwellers? We argue that these conditions are emerging, in that an increasing number of young farm dwellers constitute the precariat on farms, and this constituency both understands its rights and is more likely to assert them. Furthermore, the circulatory migration pattern means they are potentially connected with the urban precariat in shack settlements and inner city abandoned buildings, thus creating the potential for alliances around a disruptive politics. Whether climate change will lend further impetus to this politics, or exacerbate and engender a ‘slipping hold’ will be key for rural farm dweller futures.

Acknowledgments

The European Union made funding available to the Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA) for the data collection and analysis, amongst other project aspects. No funding is available for journal article publication.

Author Contributions

Donna Hornby developed the research design and survey instrument in consultation with AFRA staff and managed the field research team. She undertook data analysis with support from the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP) from the University of Pretoria, South Africa. She was the primary author, responsible for the sections on agrarian change and dynamics and the research findings. Adrian Nel helped develop the argument and was the primary editor of the text. Samuel Chadamana provided the written material on climate change. Nompilo Khanyile was a research assistant and wrote the sections on the applicable laws and mobility theory.

Conflicts of Interest

Donna Hornby and Nompilo Khanyile were employed by the Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA) for the duration of the research. Adrian Nel and Samuel Chademana declare no conflict of interest. The European Union, as the founding sponsor, had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hornby, D.; Kingwell, R.; Royston, L.; Cousins, B. Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa; UKZN Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, S. Agrarian Reform and South Africa’s Agro-Food System. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 957–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, M.; Russell, B.; Grundling, I. Still Searching for Security: The Reality of Farm Dwellers Evictions in South Africa; Nkuzi Development Association: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- AGRI, SA. Land Audit: A Transactions Approach; AGRI SA: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, B.; Hall, R. SA still struggling to ‘give back the land’. The Citizen, 13 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aliber, M.; Cousins, B. Livelihoods after Land Reform in South Africa. J. Agrar. Chang. 2013, 13, 140–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. Land reform for what? Land use, production and livelihoods. In Another Countryside: Policy Options for Land and Agrarian Reform in South Africa; Hall, R., Ed.; Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape: Cape Town, South Africa, 2009; pp. 23–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sender, J.; Johnston, D. Searching for a Weapon of Mass Production in Rural Africa: Unconvincing Arguments for Land Reform. J. Agrar. Chang. 2004, 4, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, M. South Africa Pushed to the Limit: The Political Economy of Change; Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Igumbor, E.U.; Sanders, D.; Puoane, T.R.; Tsolekile, L.; Schwarz, C.; Purdy, C.; Swart, R.; Durão, S.; Hawkes, C. “Big Food”, the Consumer Food Environment, Health, and the Policy Response in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Laughlin, B.; Bernstein, H.; Cousins, B.; Peters, P. Introduction: Agrarian Change, Rural Poverty and Land Reform in South Africa since 1994. J. Agrar. Chang. 2013, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawala, S.; Frankhauser, S. (Eds.) Economic Aspects of Adaptation to Climate Change: Costs, Benefits and Policy Instruments; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change: Executive Summary, 2006; Her Majesty’s Treasury: London, UK, 2008. Available online: http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/8AC/F7/ExecutiveSummary.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2017).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Working Group II Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ziervogel, G.; Taylor, A. Feeling Stressed: Integrating Climate Adaptation with Other Priorities in South Africa. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2008, 50, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbumozhi, V. Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Developmental Planning. Discussion Paper Presented at the ADBI Regional Workshop on Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Developmental Planning. DEAT (2004). A National Climate Change Response Strategy for South Africa; Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT): Pretoria, South Africa, 2009.

- Kaijage, H.R. A basis for climate change adaptation in Africa: burdens ahead and policy options. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2011, 4, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpie, J.; Visser, M. The Impact of Climate Change on South Africa’s Rural Areas (Chapter 4 of Financial and Fiscal Commission: Submission for the 2013/14 Division of Revenue); Financial and Fiscal Commission: Midrand, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ziervogel, G.; New, M.; Archer van Garderen, E.; Midgley, G.; Taylor, A.; Hamann, R.; Stuart-Hill, S.; Myers, J.; Warburton, M. Climate change impacts and adaptation in South Africa. WIREs Clim Chang. 2014, 5, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT). A National Climate Change Response Strategy for South Africa; Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT): Pretoria, South Africa, 2004.

- Stats SA. 2011. Census 2011. Government of South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03014/P030142011.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2017).

- O’Brien, K.; Leichenko, R. Double exposure: Assessing the impacts of climate change within the context of economic globalization. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2000, 10, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change; Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies Series; Fernwood Publishing: Black Point, NS, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Standing, G. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Treasury, P. Provincial Economic Review and Outlook: 2016–2017; Provincial Government Budget Office: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2017.

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Community Survey; Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016.

- Clark, T. Ecocriticism on the Edge: The Anthropocene as a Threshold Concept; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, T. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Term Anthropocene. Camb. J. Postcolonial Lit. Inquiry 2014, 1, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.W. The Capitalocene, Part I: On the nature and origins of our ecological crisis. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 594–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Takle, E.; Hofstrand, D. Global Warming-Impact of Climate Change on Global Agriculture; Ag Decision Maker Newsletter—lib.dr.iastate.edu; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. Available online: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-environ-020411-130608 (accessed on 28 November 2017). [CrossRef]

- Hewitson, B.C.; Tadros, M.; Jack, C. Historical Precipitation Trends over Southern Africa: A Climatology Perspective. In Climate Change and Water Resources in South Africa: Studies on Scenarios, Impacts, Vulnerabilities and Adaptation; RSA, WRC Report 1430/1/05; Schulze, R.E., Ed.; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weis, T. The Ecological Hoofprint: The Global Burden of Industrial Livestock; Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Franco, J.C.; Borras, S.M., Jr. Land concentration and land grabbing in Europe: A preliminary analysis. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 36, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P.; Schneider, M. Food Security Politics and the Millennium Development Goals. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; McMichael, P. Deepening, and repairing, the metabolic rift. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAASTD. Synthesis Report: Agriculture at a Crossroads: International Assessment of Agricultural Science and Technology for Development; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. Industrial Agriculture, Agroecology and Climate Change. Centre for Ecoliteracy. 2015. Available online: https://www.ecoliteracy.org/article/industrial-agriculture-agroecology-and-climate-change# (accessed on 3 December 2017).

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Altieri, M.A. Agroecology, Food Sovereignty, and the New Green Revolution. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. Peasants and the Art of Farming: A Chayanovian Manifesto; Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies Series 2; Fernwood: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pinock, S. Peak Phosphorus Fuels Food Fears. ABC Science. 5 August 2010. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2010/08/05/2973513.htm (accessed on 2 December 2017).

- Raleigh, C.; Jin, C.H.; Kniveton, D. The devil is in the details: An investigation of the relationships between conflict, food price and climate across Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 32, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atteridge, A.; Remling, E. Is adaptation reducing vulnerability or redistributing it? WIREs Clim. Chang. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, J.; du Toit, A. A Deepening Divide in the Countryside: Restructuring and Rural Livelihoods in the South African Wine Industry. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2005, 31, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breman, J. A Bogus Concept? New Left Rev. 2013, 84, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bernado, F. The impossibility of precarity. Radic. Philos. 2016, 198, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Munk, R. The Precariat: A view from the South. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, M. Wageless Life. New Left Rev. 2010, 66, 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Breman, J. Footloose Labour: Working in India’s Informal Economy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]