Nonlinear Impact of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience: A Threshold Effect Analysis Based on City-Level Panel Data from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Impacts of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience

2.2. Threshold Effects of Regional Economic Development Level

3. Research Methods and Data Sources

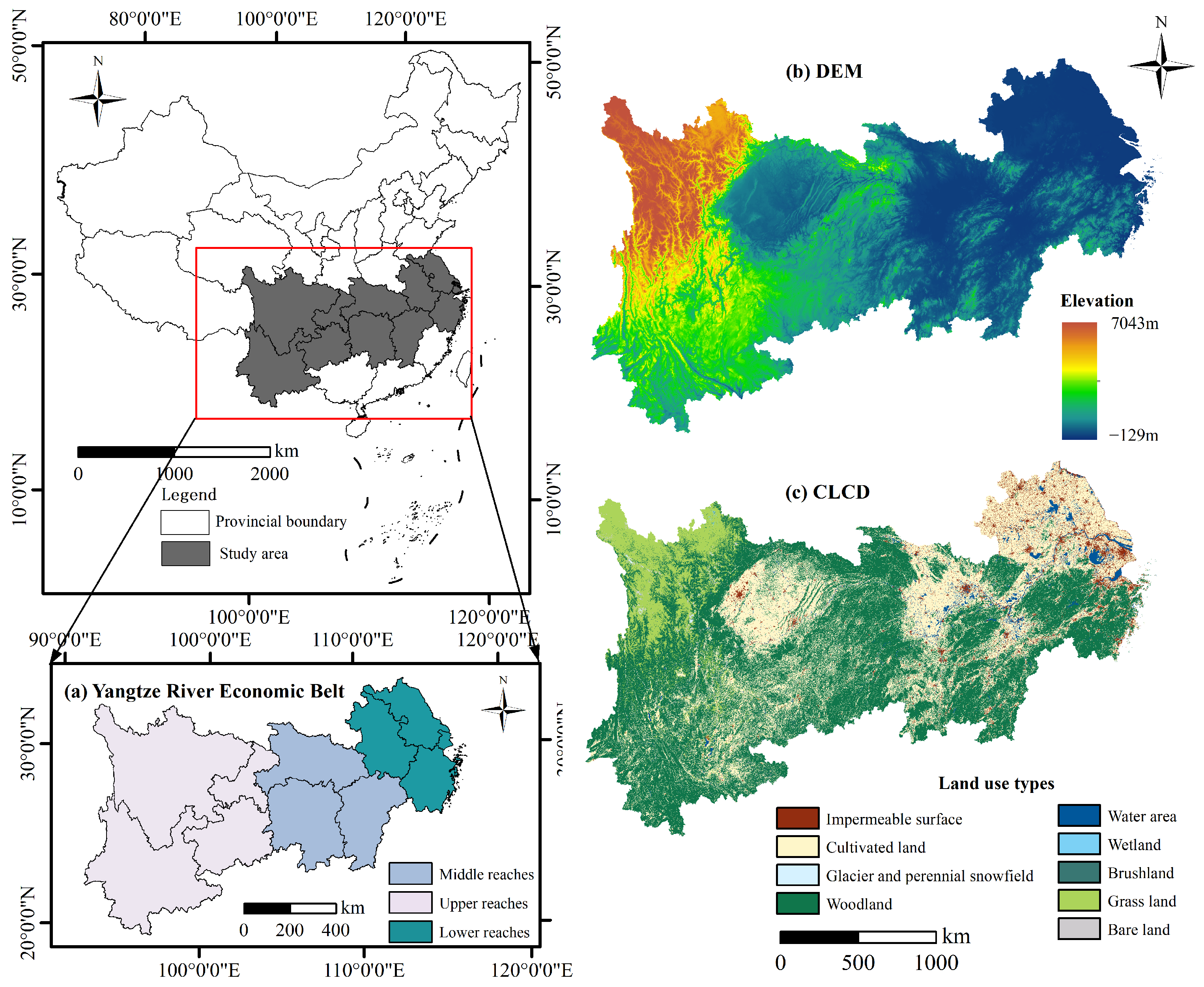

3.1. Description of the Study Area

3.2. Research Methodology

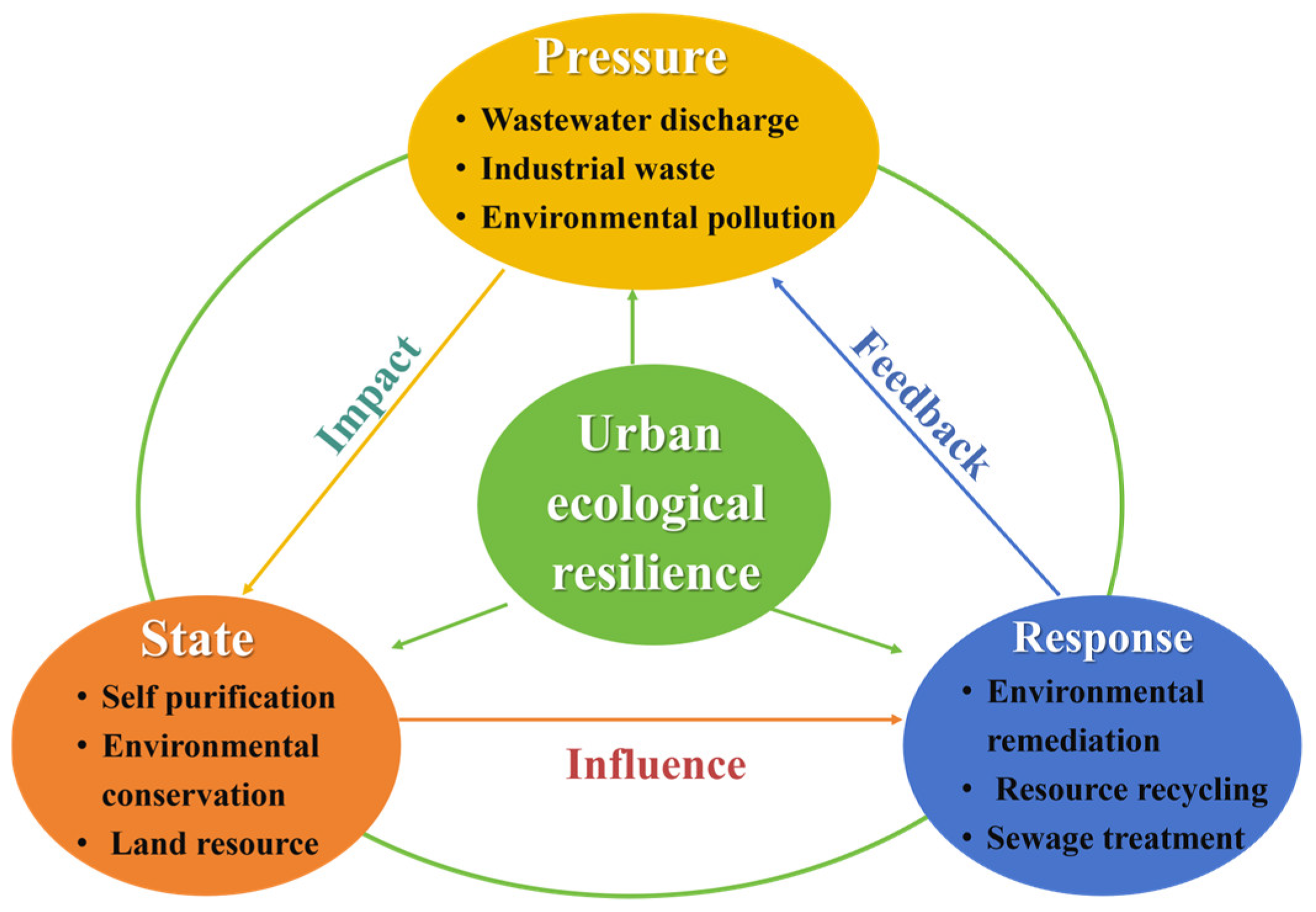

3.2.1. Development of the Urban Ecological Resilience Indicator System

3.2.2. Entropy Weight-TOPSIS Method

3.2.3. Population Shrinkage Indicator

3.2.4. Threshold Effect Model

- (1)

- Selection of variables for the threshold effect model

- (2)

- Model assumptions

3.3. Data Sources

4. Results

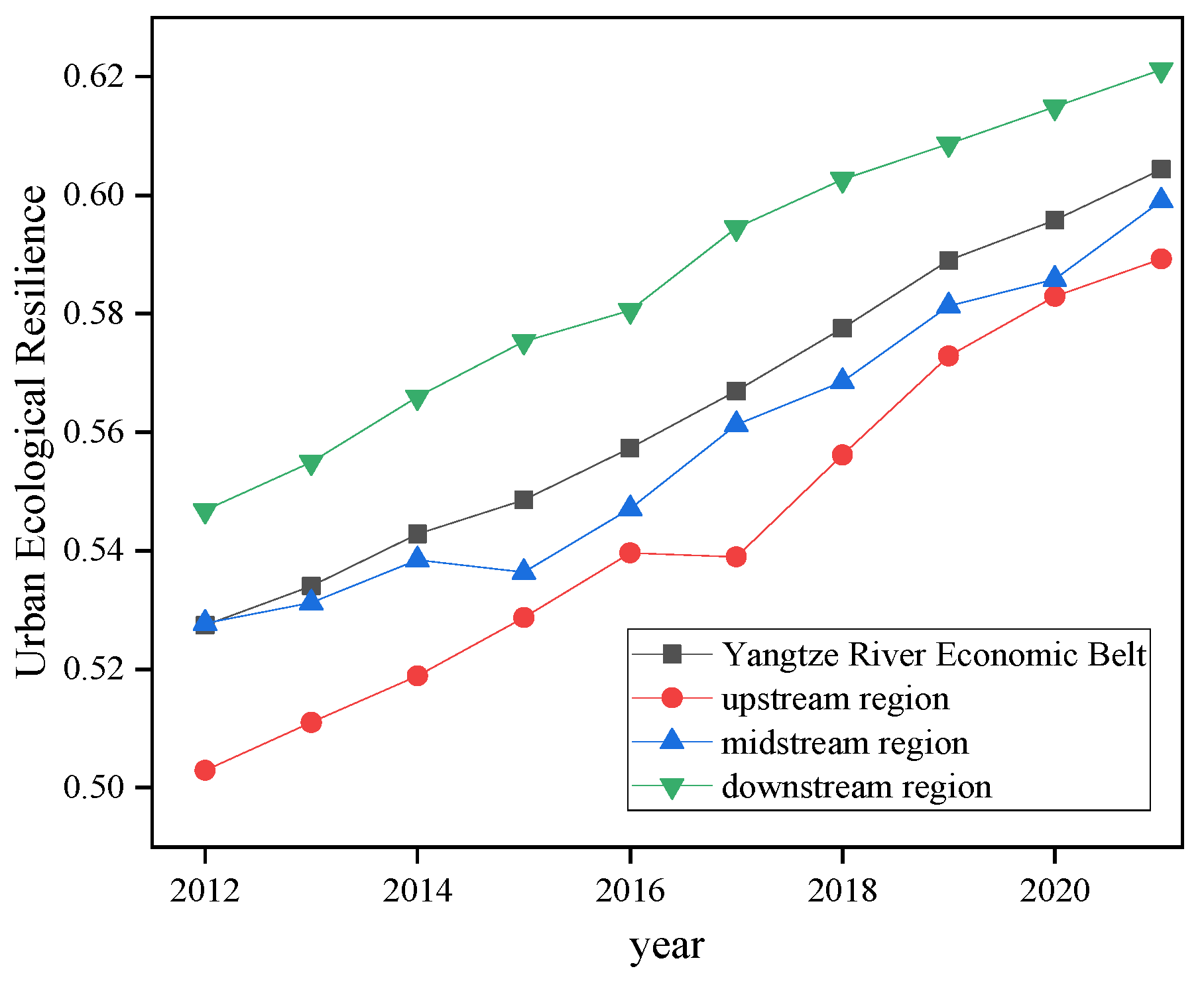

4.1. Temporal and Spatial Evolution Characteristics of Urban Ecological Resilience

4.1.1. Temporal Trends

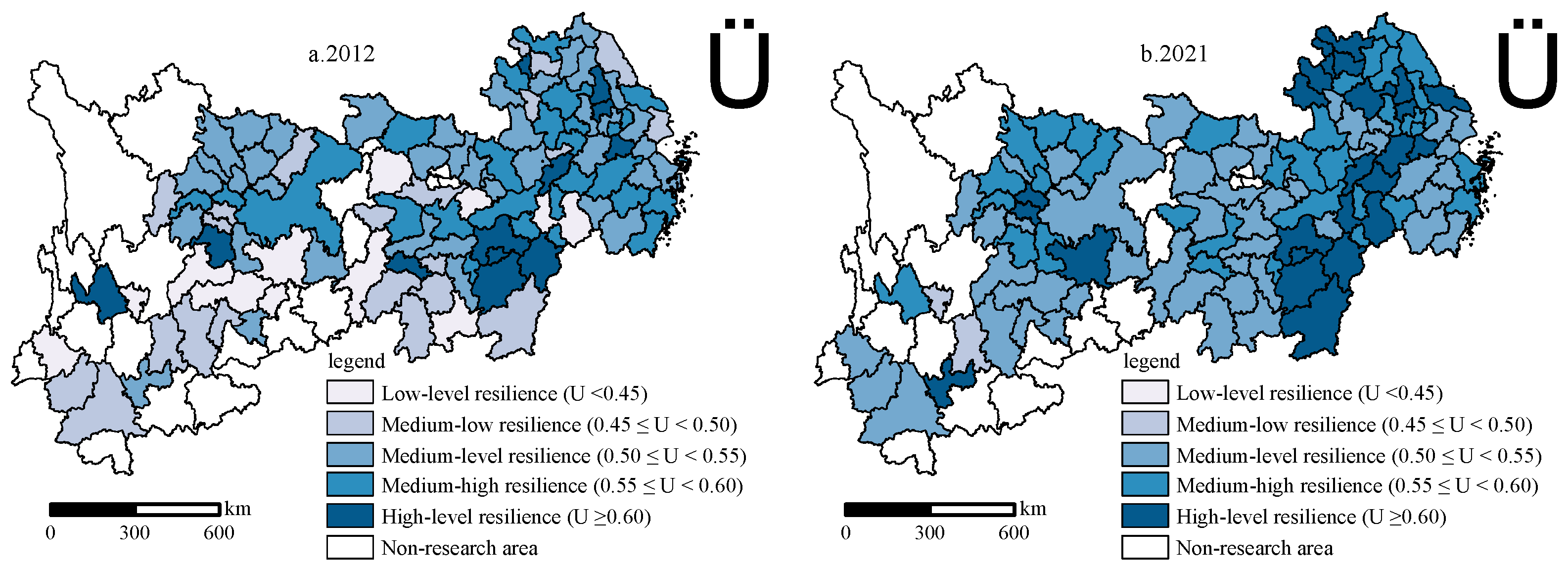

4.1.2. Spatial Variation

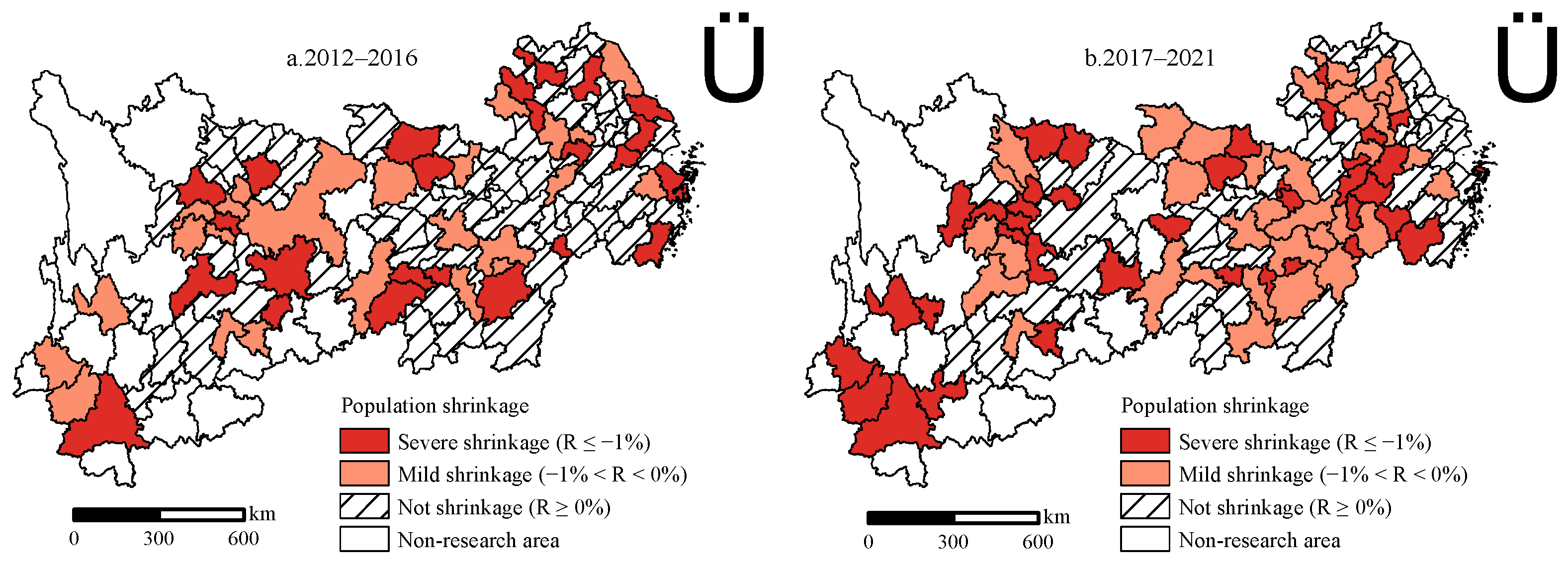

4.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of Population Shrinkage

4.2.1. Temporal Variation

4.2.2. Spatial Variation

4.3. Impacts of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience

4.3.1. Threshold Effect Model Test

4.3.2. Threshold Regression Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Population Shrinkage and Urban Ecological Resilience

5.2. Effect of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Urban Ecological Resilience: The overall level of urban ecological resilience in the economic belt shows a gradual improvement, albeit with significant regional disparities, exhibiting a spatial pattern of “higher resilience in the east and lower resilience in the west.” Moreover, the downstream region demonstrates the highest resilience, benefiting from a developed economy, abundant resources, and advanced technological conditions. The midstream region reflects a moderate level of resilience owing to the cumulative effects of industrial pollution and ecological pressures. Contrastingly, the upstream region, characterized by high ecological sensitivity and insufficient infrastructure, shows relatively weaker resilience.

- (2)

- Population Shrinkage Trends: The extent of population shrinkage in the economic belt shows a trend of increasing intensity, with its spatial scope expanding. Severe population shrinkage is mainly concentrated in upstream resource-based cities and economically underdeveloped areas. Contrastingly, economically developed downstream regions and central cities still experience population growth, reflecting a broader trend of population and resource concentration in large urban centers.

- (3)

- Effect of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience. The influence of population shrinkage on urban ecological resilience shows an inverted U-shaped nonlinear pattern, moderated by regional economic development levels. In areas with low economic development, the positive effects of population shrinkage on ecological resilience are insignificant. At moderate economic development levels, population shrinkage improves ecological resilience through resource optimization and economic restructuring. However, at high economic development levels, population shrinkage leads to economic stagnation, infrastructure underutilization, and a decline in ecological governance capacity, significantly weakening ecological resilience.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, D.; Luan, W.; Zhang, X. Projecting spatial interactions between global population and land use changes in the 21st century. npj Urban Sustain. 2023, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Dong, T.; Xu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Geographic micro-process model: Understanding global urban expansion from a process-oriented view. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 87, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K. Polycrisis in the Anthropocene as a key research agenda for geography: Ontological delineation and the shift to a postdisciplinary approach. Folia Geogr. 2024, 66, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina, M.; Ivonne, A.; Sylvie, F.; Emmanuèle, C. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, H.; He, H.; Wu, Y.; Delang, C.; Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Yao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Gomez, C. Quantifying the heterogeneity of urban water resources utilization efficiency through meta-frontier super SBM model: Application in the yellow river Basin. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 485, 144410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Miao, Y.; Wang, C. Spatiotemporal evolution of urban shrinkage and its impact on urban resilience in three provinces of northeast China. Land 2023, 12, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzebski, M.; Elmqvist, T.; Gasparatos, A.; Fukushi, K.; Eckersten, S.; Haase, D.; Goodness, J.; Khoshkar, S.; Saito, O.; Takeuchi, K.; et al. Ageing and population shrinking: Implications for sustainability in the urban century. npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Huang, X. Assessment the urbanization sustainability and its driving factors in Chinese urban agglomerations: An urban land expansion-Urban population dynamics perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Káčerová, M.; Ondoš, S.; Kusendová, D. A Spatial Analysis of Demographic and Curricular Influences on Secondary Education in Slovakia. Folia Geogra. 2024, 66, 36–57. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, M.; Marzluff, J. Ecological resilience in urban ecosystems: Linking urban patterns to human and ecological functions. Urban Ecosyst. 2004, 7, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, W.; Huang, R. The multidimensional differences and driving forces of ecological environment resilience in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, S. Interaction mechanisms of urban ecosystem resilience based on pressure-state-response framework: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Niu, J. Dynamic evolution and obstacle factors of urban ecological resilience in Shandong Peninsula urban agglomeration. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hou, J.; Ma, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal differentiation of the composite ecosystem resilience in the ecologically fragile area in the upper reaches of the Yellow River: A case study in Ningxia. Arid Zone Res. 2023, 40, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakos, V.; Kefi, S. Ecological resilience: What to measure and how. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 043003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zeng, F.; Loo, B.; Zhong, Y. The evolution of urban ecological resilience: An evaluation framework based on vulnerability, sensitivity and self-organization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 116, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhu, X.; Wu, H.; Li, Z. Assessment of urban ecological resilience and its influencing factors: A case study of the BeijingTianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration of China. Land 2022, 11, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, L. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and influencing factors of urban ecological resilience in the Yellow River Basin. Arid Land Geogr. 2024, 47, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, T.; Hu, H.; Fu, S.; Kong, A. Spatio-temporal differentiation and influencing factors of urban ecological resilience in the Yangtze River Delta. Areal Res. Dev. 2023, 42, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, X.; Dong, Y.; Guan, J.; Wang, J.; Xi, Z.; Li, C. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity and influencing factors in the synergistic enhancement of urban ecological resilience: Evidence from the Yellow River Basin of China. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 173, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Liu, K. Foreign direct investment, environmental regulation and urban green development efficiency—An empirical study from China. Appl. Econ. 2023, 56, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, X. Coupling and Coordination Mechanism of New Urbanization and Ecological Resilience in Central Cities Along the Yellow River. East China Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Zhang, C.; Jia, T.; Huang, Z.; Xu, M. Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics and driving mechanisms of urban ecological resilience in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 4592–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Haase, A.; Rink, D. Conceptualizing the nexus between urban shrinkage and ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 132, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. The phenomenon, development differentiation and spatial mechanism of local cities shrinkage in Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 55, 129–143+179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippelli, G.; Morrison, D.; Cicchella, D. Urban Geochemistry and Human Health. Elements 2012, 8, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qu, J. Study on the impact of urban shrinkage on economic development: “facilitate” or ”hinder”. Urban Dev. Stud. 2020, 27, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Sha, S.; Cheng, W. Revealing the heterogeneity of social capital in shrinking cities from a social infrastructure perspective: Evidence from Hegang, China. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 159, 103087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-X.; Cheng, J.-W.; Philbin, S.P.; Ballesteros-Perez, P.; Skitmore, M.; Wang, G. Influencing factors of urban innovation and development: A grounded theory analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2079–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F. Spatial Allocation of the Equalization of Medical and Health Resources in China from the Perspective of Permanent Population. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Dong, L. Research on spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors of county-level urban shrinkage in urbanizing China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 109, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, H.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y. An assessment model for urban resilience based on the pressure-state-response framework and BP-GA neural network. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; Xiong, Y. Ecological security assessment of China based on the Pressure-State-Response framework. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Jiang, R.; Zhu, Y.; García-Lorenzo, I.; Chu, J.; Sumaila, U.R. Global sustainability assessment of cephalopod fisheries based on pressure-state-response framework. iScience 2024, 27, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Luo, Y. Research on farmland abandonment from the perspective of historical evolution based on “Pressure-State-Response” Model. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 25, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Feng, H.; Arashpour, M.; Zhang, F. Enhancing urban flood resilience: A coupling coordinated evaluation and geographical factor analysis under SES-PSR framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 101, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Wang, C.; Tang, C. Impact of digital technology innovation on urban ecological resilience. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 7590–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, N.; Shen, Z. Evaluation of the water quality monitoring network layout based on driving-pressure-state-response framework and entropy weight TOPSIS model: A case study of Liao River, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwest, F. Demographic Decline and Local Government Strategies: A Study of Policy Change in The Netherlands; Eburon: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Qi, W.; Qi, H.; Liu, S. The evolution of regional population decline and its driving factors at the county level in China from 1990 to 2015. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Renewable energy technology innovation and urbanization: Insights from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 102, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, N. Impact of regional integration policy on urban ecological resilience: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 485, 144375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Naseem, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Azam, T. Assessing the effects of fuel energy consumption, foreign direct investment and GDP on CO2 emission: New data science evidence from Europe & Central Asia. Fuel 2022, 314, 123098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B. Threshold Effects in Non-dynamic Panels: Estimation, Testing, and Inference. J. Econom. 1999, 2, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, S. Effects of regional population shrinkage on economic growth and the underlying mechanism. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, D.; Schwarz, K.; Shuster, W.; Berland, A.; Chaffin, B.; Garmestani, A.; Hopton, M. Ecology for the Shrinking City. BioScience 2016, 66, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.; Lobo, J.; Helbing, D.; Kühnert, C.; West, G. Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7301–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhou, G.; Sun, H.; Fu, H.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y. Regrowth or smart decline? A policy response to shrinking cities based on a resilience perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Level | Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Tertiary Indicator | Unit | Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban ecological resilience | Pressure | Wastewater discharge | Per capita industrial wastewater discharge | t | − |

| Industrial waste | Per capita sulfur dioxide emissions | t | − | ||

| Environmental pollution | Per capita industrial soot and dust emissions | t | − | ||

| State | Self-purification | Green coverage rate in built-up areas | % | + | |

| Environmental conservation | Per capita park green space area | km2 | + | ||

| Land resource | Per capita built-up area | km2 | + | ||

| Response | Environmental remediation | Harmless treatment rate of household waste | % | + | |

| Resource recycling | Comprehensive utilization rate of general industrial solid waste | % | + | ||

| Sewage treatment | Centralized treatment rate of wastewater at sewage treatment plants | % | + |

| Type | 2012–2016 | 2017–2021 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Upstream Region | Midstream Region | Downstream Region | Overall | Upstream Region | Midstream Region | Downstream Region | |

| Mild shrinkage | 24 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 33 | 6 | 17 | 33 |

| Severe shrinkage | 24 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 39 | 18 | 10 | 24 |

| Total | 48 | 18 | 14 | 16 | 72 | 24 | 27 | 48 |

| Threshold Variable | BS Count | Threshold Type | p-Value | Threshold Value | 95% Confidence Interval of the Threshold | Critical Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 5% | 1% | ||||||

| EDL | 1000 | Dual threshold | 0.0320 | 4.5396 | [4.5280, 4.5470] | 15.8795 | 19.4562 | 28.0396 |

| 1000 | Triple threshold | 0.0475 | 4.5948 | [4.5865, 4.6101] | 15.7971 | 19.5250 | 27.9416 | |

| Threshold Reversion Effect | Results for the Full Sample |

|---|---|

| Single threshold value | 4.540 |

| Double threshold value | 4.594 |

| UER (EDLit ≤ γ1) | 0.505 (0.166) |

| UER (γ1 < EDLit ≤ γ2) | 0.616 ** (0.049) |

| UER (EDLit > γ2) | −0.502 ** (0.013) |

| _cons | 0.255 (0.098) |

| R2 | 0.630 |

| F test | F (8109) = 32.9 Prob > F = 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Cai, Y. Nonlinear Impact of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience: A Threshold Effect Analysis Based on City-Level Panel Data from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land 2026, 15, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020261

Chen X, Zhao Y, Zhou C, Cai Y. Nonlinear Impact of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience: A Threshold Effect Analysis Based on City-Level Panel Data from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land. 2026; 15(2):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020261

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xuan, Yuluan Zhao, Chunfang Zhou, and Yonglong Cai. 2026. "Nonlinear Impact of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience: A Threshold Effect Analysis Based on City-Level Panel Data from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China" Land 15, no. 2: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020261

APA StyleChen, X., Zhao, Y., Zhou, C., & Cai, Y. (2026). Nonlinear Impact of Population Shrinkage on Urban Ecological Resilience: A Threshold Effect Analysis Based on City-Level Panel Data from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land, 15(2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020261