Multi-Decadal Vegetation Phenology Dynamics in China’s Arid Northwest: Unraveling Climate–Terrain Interactions via PLS-SEM

Abstract

1. Introduction

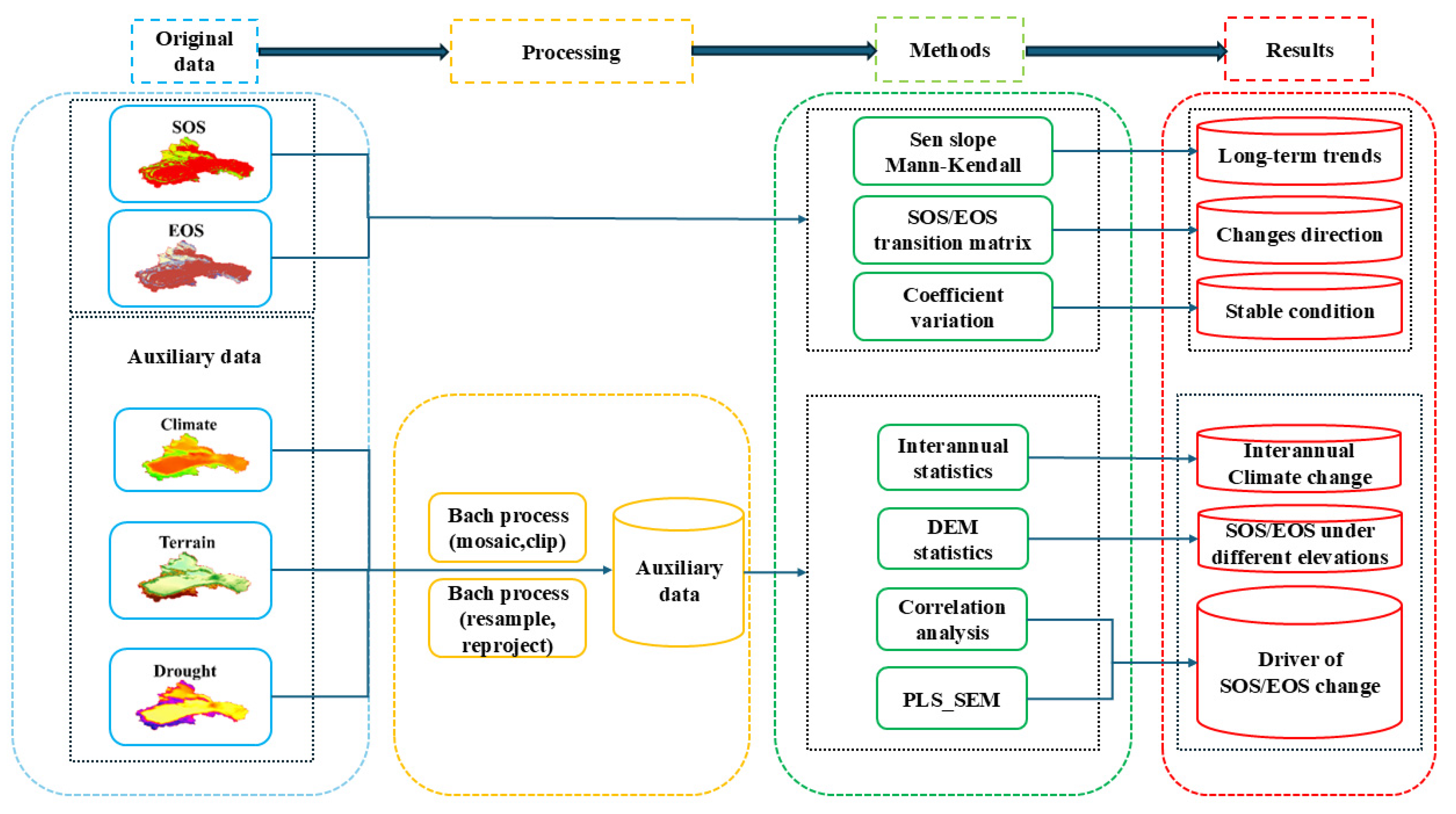

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Trend Analysis

2.3.2. Coefficient of Variation

2.3.3. Correlation Analysis

2.3.4. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM)

3. Results

3.1. Temporal and Spatial Variation Characteristics of SOS/EOS

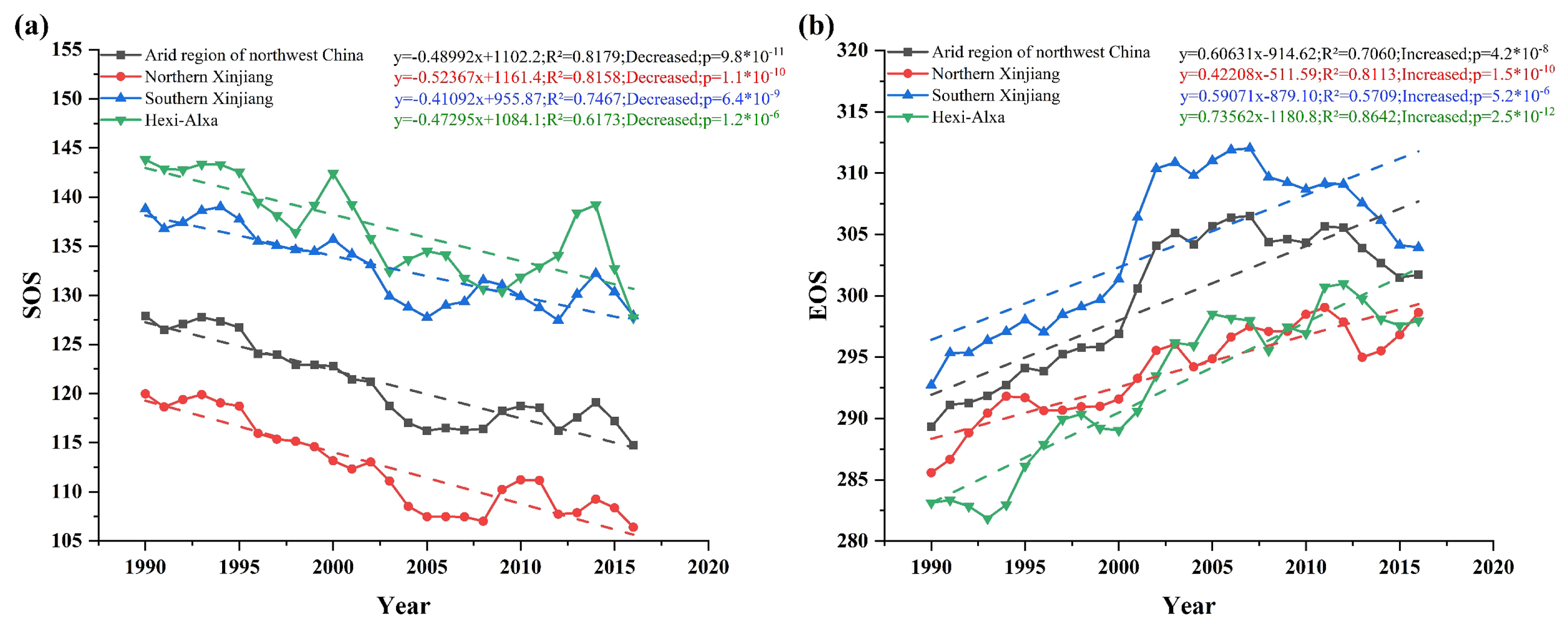

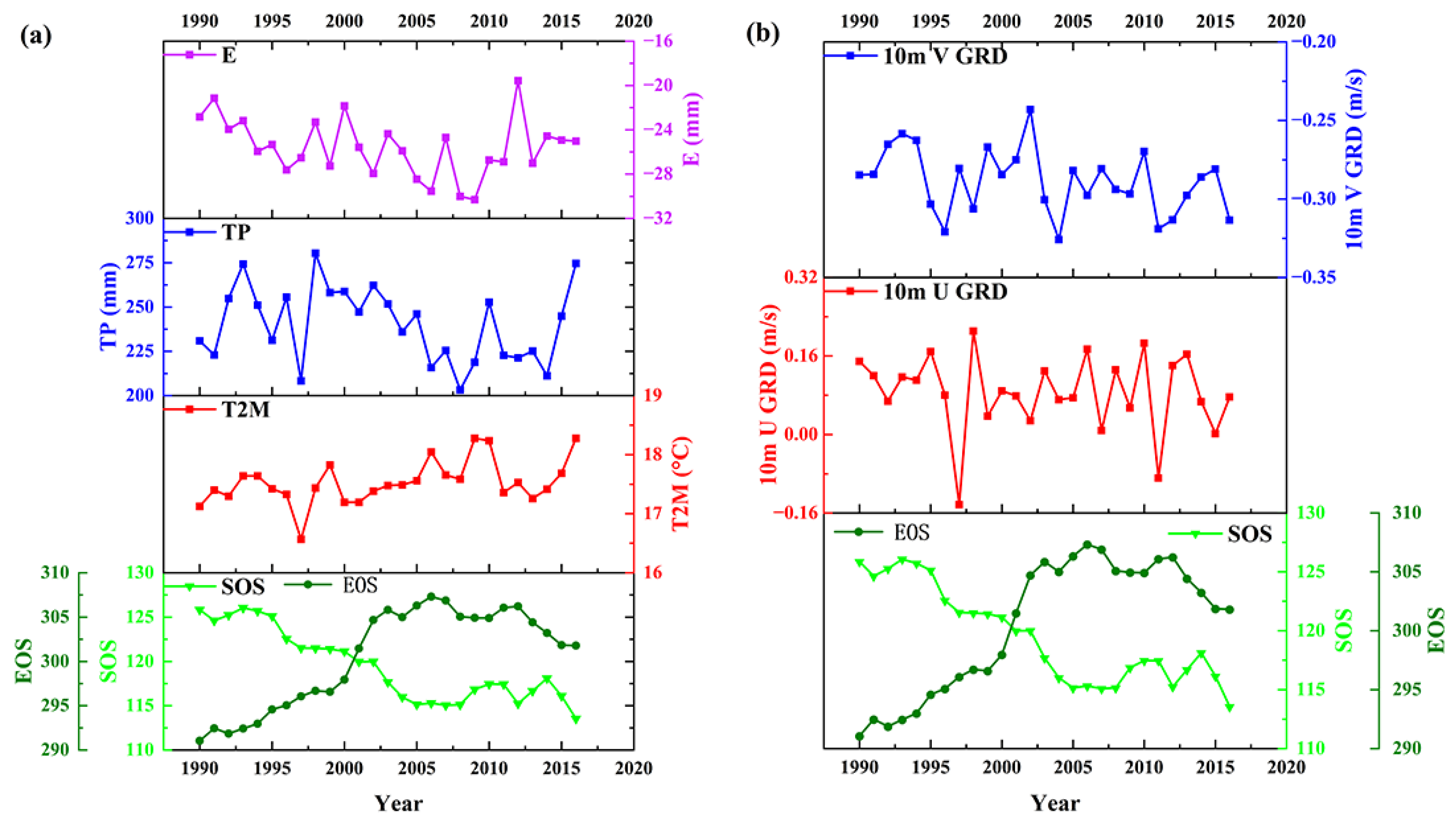

3.1.1. Temporal Variation Characteristics of SOS/EOS

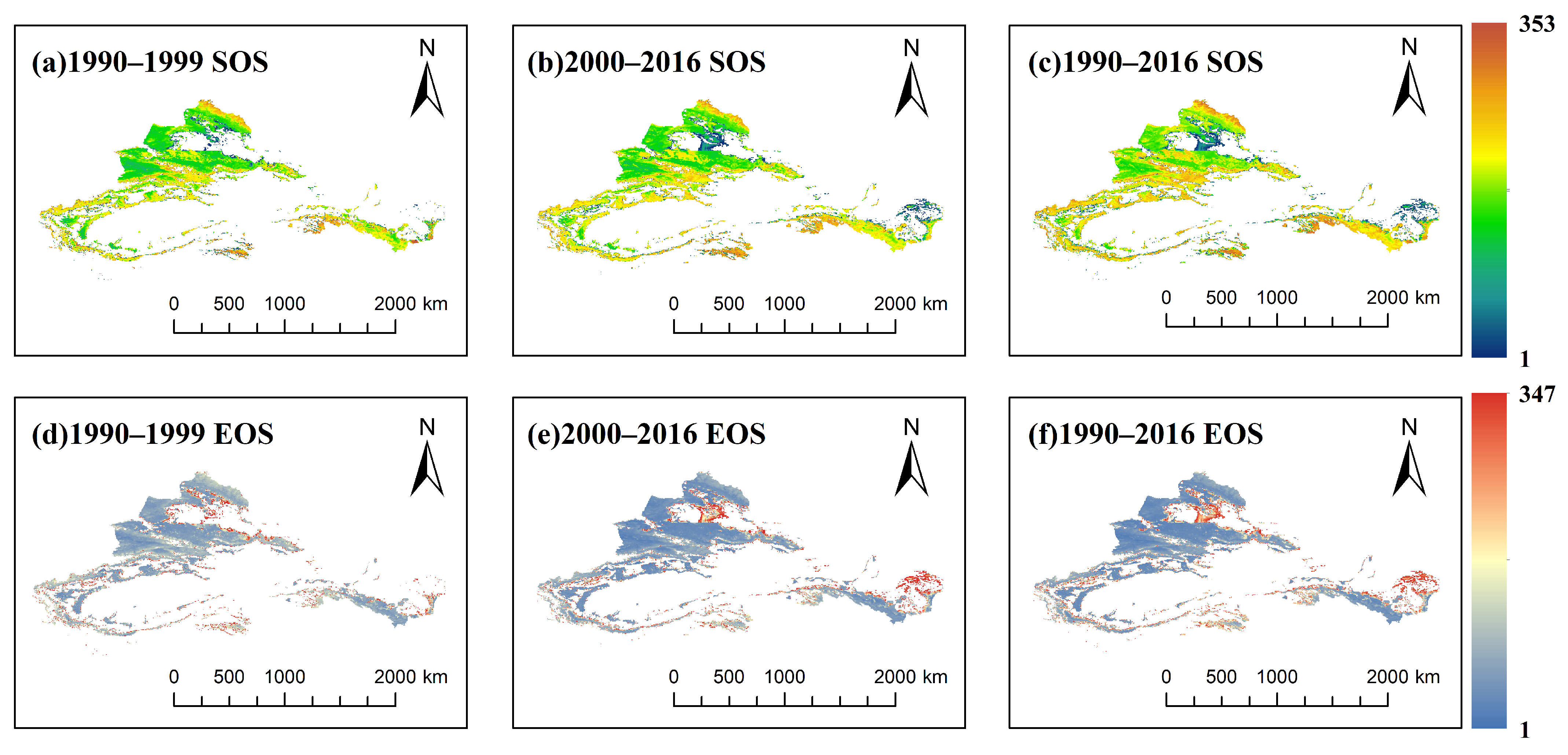

3.1.2. Spatial Variation Characteristics of SOS/EOS

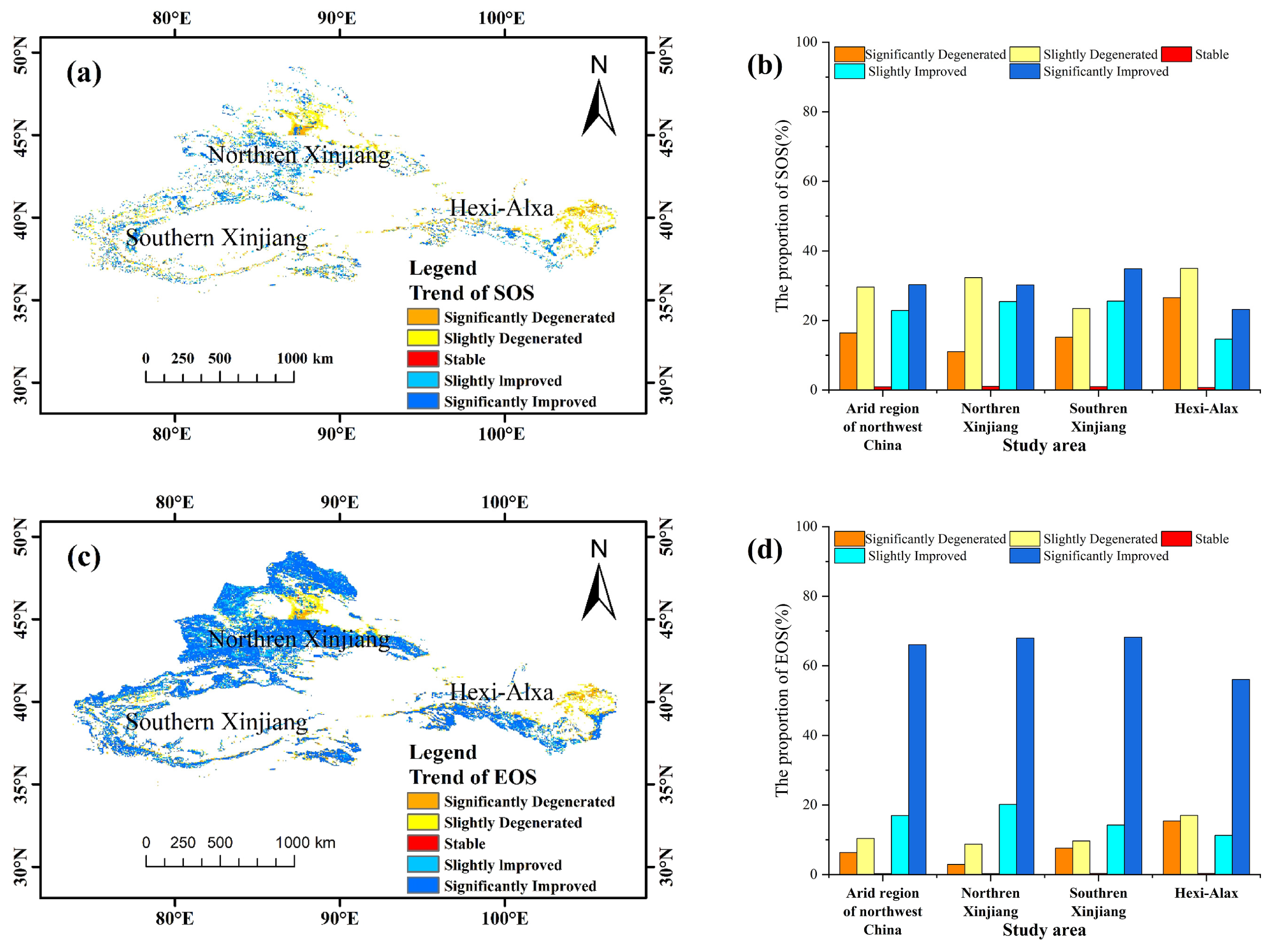

3.2. Trend of SOS/EOS Change

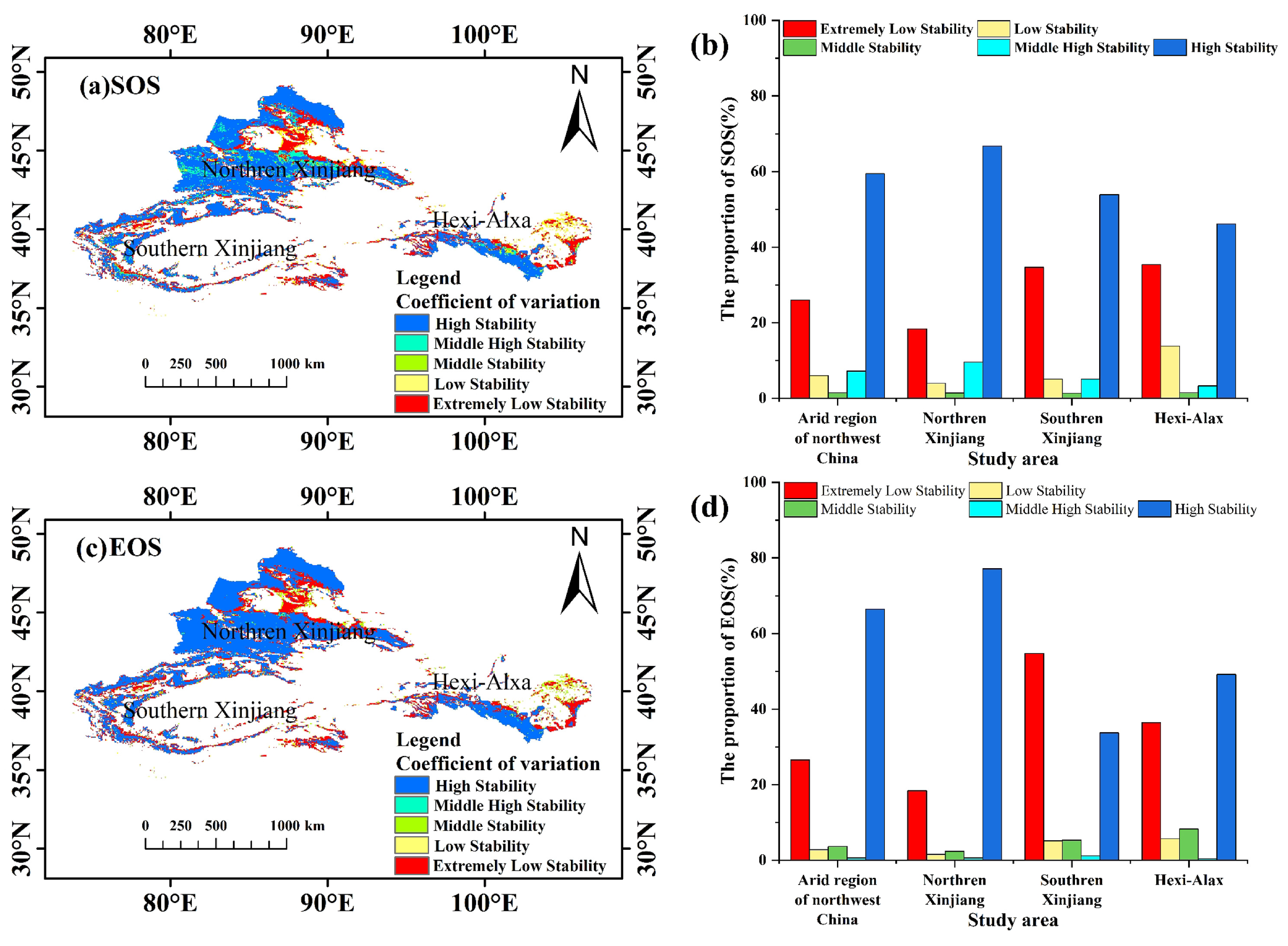

3.3. Stability Analysis of SOS/EOS

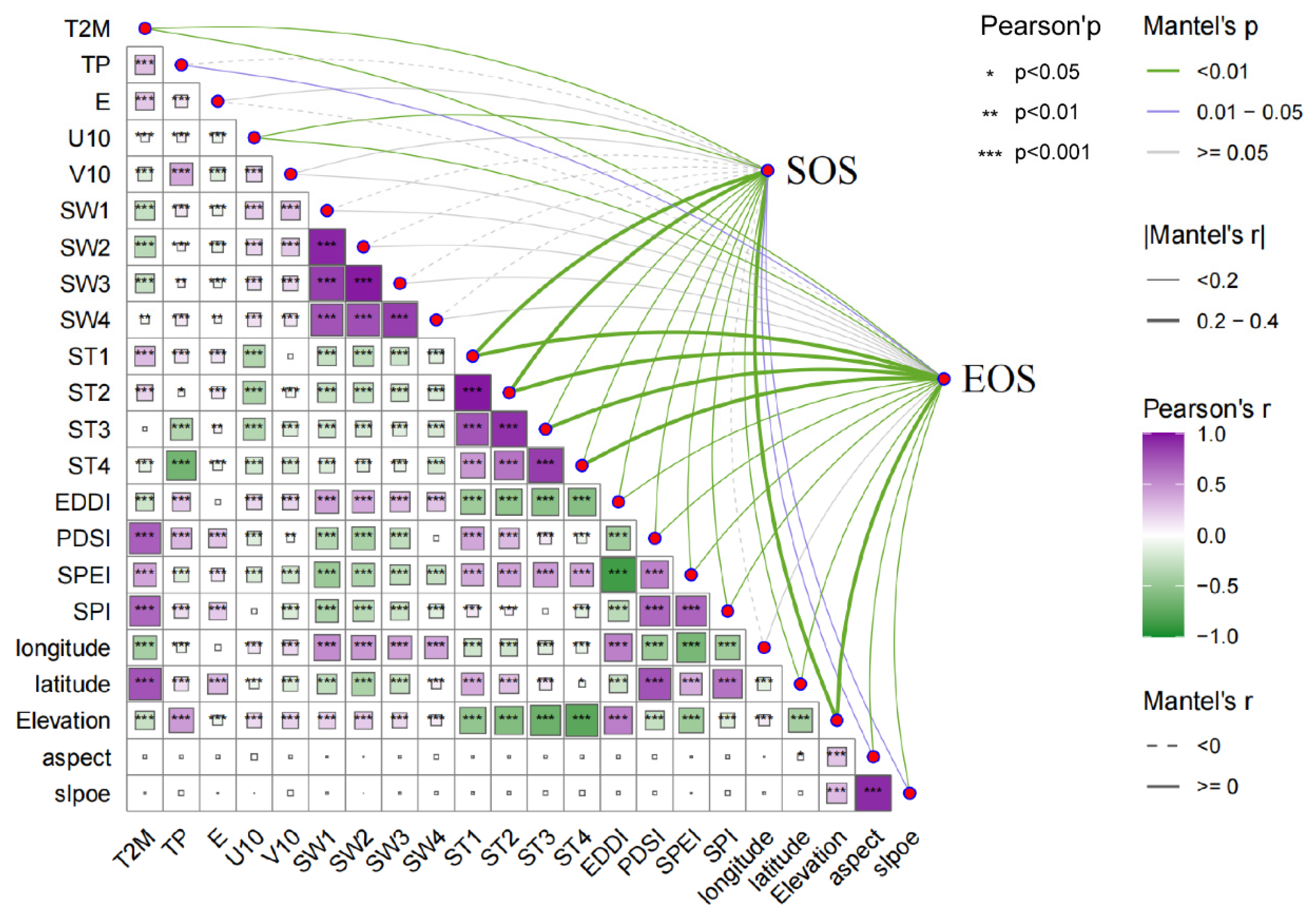

3.4. Analysis of Influencing Factors of SOS/EOS

3.4.1. Interannual Climate Change

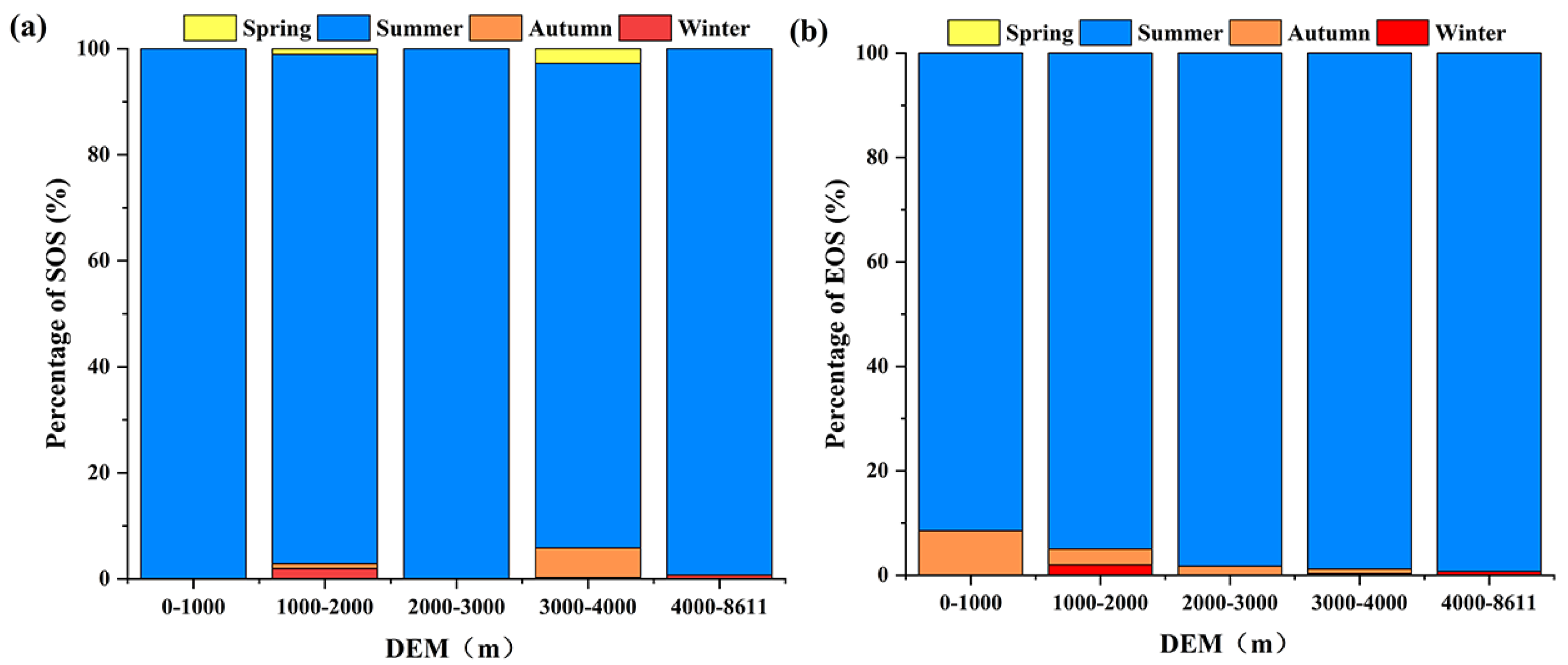

3.4.2. The Variation in SOS/EOS Under Different Elevations

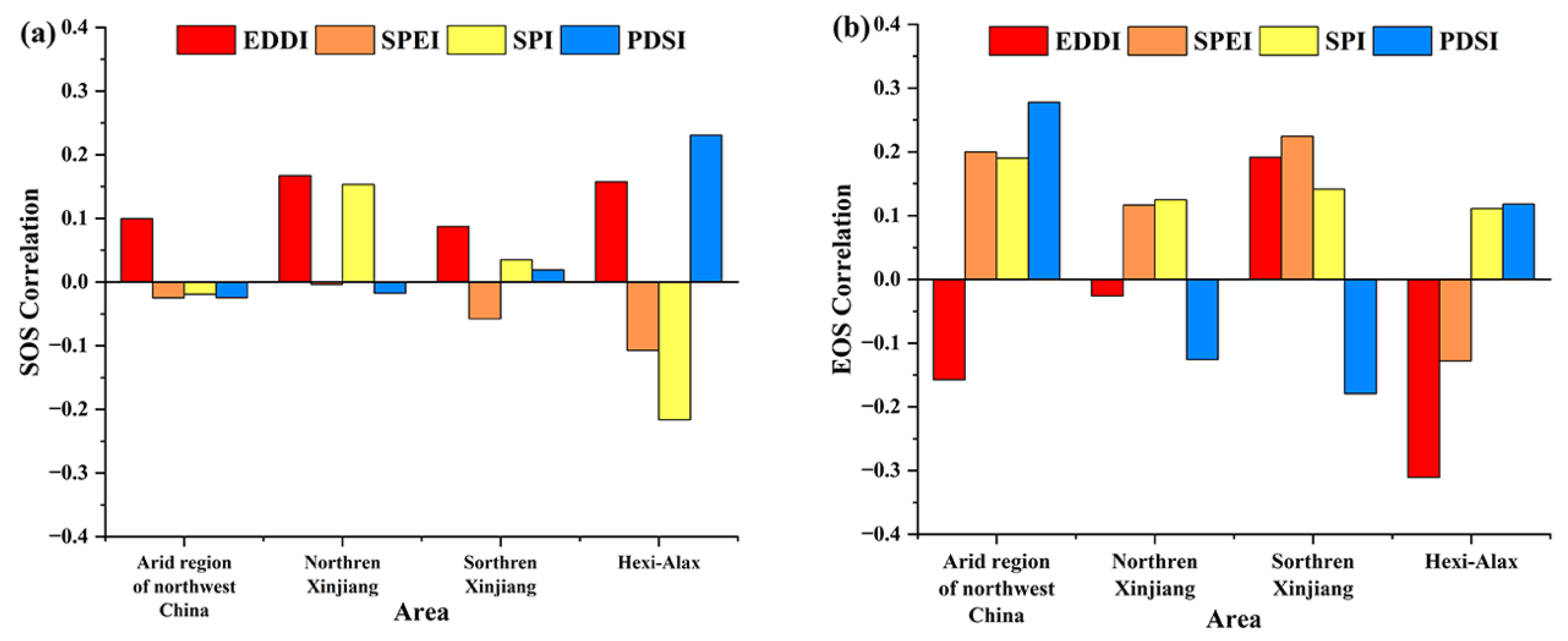

3.4.3. Correlation Analysis of Drought Index

3.4.4. Analysis of the Changing Driving Force of SOS/EOS

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution Features of SOS/EOS

4.2. Effects of Driving Factors on SOS/EOS Changes

4.3. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

- From 1990 to 2016, the average yearly SOS and EOS were 114.7 Day and 301.7 Day, with higher numbers in the northwest and lower numbers in the southeast. The results indicate a prolongation of the vegetation growing season.

- Interannual fluctuations showed the SOS and EOS coefficient of variation (CV) values of 0.230 and 0.234, respectively, with southeastern regions displaying higher instability than northwestern counterparts.

- The spatial variation in SOS/EOS is primarily influenced by meteorological and geographical conditions, with an explanatory power exceeding 30%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, Y.H.; Zhao, H.; Piao, S.; Peaucelle, M.; Peng, S.; Zhou, G.; Ciais, P.; Huang, M.; Menzel, A.; Penuelas, J.; et al. Declining global warming effects on the phenology of spring leaf unfolding. Nature 2015, 526, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudoh, H. Molecular phenology in plants: In natura systems biology for the comprehensive understanding of seasonal responses under natural environments. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Elberling, B.; Westergaard-Nielsen, A. Drivers of contemporary and future changes in Arctic seasonal transition dates for a tundra site in coastal Greenland. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, A.; Sparks, T.H.; Estrella, N.; Koch, E.; Aasa, A.; Ahas, R.; Alm-Kübler, K.; Bissolli, P.; Braslavská, O.; Briede, A.; et al. European phenological response to climate change matches the warming pattern. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ding, J.; Amantai, N.; Xiong, J.; Wang, J. Responses of vegetation cover to hydro-climatic variations in Bosten Lake Watershed, NW China. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1323445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Zhou, G.; He, Q.; Wu, B.; Lv, X. Predrought and Its Persistence Determined the Phenological Changes of Stipa krylovii in Inner Mongolia. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, A.; Janssens, I.A.; Fu, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, L.; Lian, X.; Shen, M.; Zhu, X. Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1922–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Q.; Wu, X.; Ma, X. Recent advances in remote sensing of vegetation phenology: Retrieval algorithm and validation strategy. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2022, 26, 431–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z. The Research of the Phenology Change and It’s Response to Geographical Elements in Qilian Mountains from 1982 to 2014. Doctoral Dissertation, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Han, L.; Han, L.; Zhu, L. How Well Do Deep Learning-Based Methods for Land Cover Classification and Object Detection Perform on High Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery? Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simović, I.; Šikoparija, B.; Panić, M.; Radulović, M.; Lugonja, P. Remote sensing of poplar phenophase and leaf miner attack in urban forests. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogno-Mondino, E.; Fissore, V. Reading Greenness in Urban Areas: Possible Roles of Phenological Metrics from the Copernicus HR-VPP Dataset. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudani, K.; Hmimina, G.; Delpierre, N.; Pontailler, J.-Y.; Aubinet, M.; Bonal, D.; Caquet, B.; de Grandcourt, A.; Burban, B.; Flechard, C.; et al. Ground-based Network of NDVI measurements for tracking temporal dynamics of canopy structure and vegetation phenology in different biomes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 123, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Meng, S.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Z. Phenological Changes and Their Influencing Factors under the Joint Action of Water and Temperature in Northeast Asia. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Fan, W. Spatiotemporal Variations of Forest Vegetation Phenology and Its Response to Climate Change in Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, J.; Jia, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Du, H.; Han, R.; Ye, Y. Spatio-temporal dynamics of vegetation over cloudy areas in Southwest China retrieved from four NDVI products. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Peng, J.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Wang, H.; Beguería, S.; Andrew Black, T.; Jassal, R.S.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, W.; et al. Increased drought effects on the phenology of autumn leaf senescence. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Liu, Y. Spatiotemporal dynamics of vegetation net ecosystem productivity and its response to drought in Northwest China. GISci. Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2194597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pan, J. Spatiotemporal changes in vegetation net primary productivity in the arid region of Northwest China, 2001 to 2012. Front. Earth Sci. 2017, 12, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S. Vegetation phenology response to climate change in China. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 58, 424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Ren, Z. Vegetation Coverage Change and lts Relationship with ClimateFactors in Northwest China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2012, 45, 1954–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Xun, S.; Lai, D.; Fan, Y.; Li, Z. Changes in daily climate extremes in the arid area of northwestern China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 112, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zulkar, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, T.; Xu, W. Changes in Vegetation Coverage and Migration Characteristics of Center of Gravity in the Arid Desert Region of Northwest China in 30 Recent Years. Land 2022, 11, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Hao, X. Spatiotemporal change and drivers analysis of desertification in the arid region of northwest China based on geographic detector. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, B.; Sun, Z.; Yan, J.; Ren, Y.; Guo, L. Spatial patterns of climate change and associated climate hazards in Northwest China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Huang, C. Vegetation Change and Its Response to Climate Extremes in the Arid Region of Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Fang, G. Dynamics of temperature and precipitation extremes and their spatial variation in the arid region of northwest China. Atmos. Res. 2014, 138, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Ling, H.; Deng, M.; Han, F.; Yan, J.; Deng, X.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, W. Past and projected future patterns of fractional vegetation coverage in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Peng, W.; Xiang, J. Spatiotemporal variations and driving mechanisms of vegetation coverage in the Wumeng Mountainous Area, China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.F.; Shi, S.H.; Huang, X.M. The application of structural equation modeling in ecology based on R. Chin. J. Ecol. 2022, 41, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Tang, Y.; Dong, L.; Wang, S.; Yu, B.; Wu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, Y. Temperature-dominated spatiotemporal variability in snow phenology on the Tibetan Plateau from 2002 to 2022. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 1817–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Loiacono, E.T. A joint use of PLS regression and PLS path modelling for a data analysis approach to latent variable modelling. In Proceedings of the 2010 Conference of the International Federation of Classification Societies (IFCS), Dresden, Germany, 13–18 March 2009; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Shirkey, G.; John, R.; Wu, S.R.; Park, H.; Shao, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Ecological Studies: An Updated Review. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davino, C.; Dolce, P.; Taralli, S.; Vistocco, D. Composite-Based Path Modeling for Conditional Quantiles Prediction. An Application to Assess Health Differences at Local Level in a Well-Being Perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 161, 907–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ge, C.; Zong, S.; Wang, G. Drought Assessment on Vegetation in the Loess Plateau Using a Phenology-Based Vegetation Condition Index. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Bian, Z.; Mu, S.; Yuan, J.; Chen, F. Effects of Climate Change on Land Cover Change and Vegetation Dynamics in Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Fang, G.; Li, Y. Multivariate assessment and attribution of droughts in Central Asia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zan, M.; Kong, J.; Yang, S.; Xue, C. Phenology of Vegetation in Arid Northwest China Based on Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Forests 2023, 14, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, Y.S.; Li, M.-H. Flash drought evaluation using evaporative stress and evaporative demand drought indices: A case study from Awash River Basin (ARB), Ethiopia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.Y.; Wan Jaafar, W.Z.; Othman, F.; Lai, S.H.; Mei, Y.; Juneng, L. Assessment of Evaporative Demand Drought Index for drought analysis in Peninsular Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, A.A.; Rosa, R.D.; Pereira, L.S. Climate trends and behaviour of drought indices based on precipitation and evapotranspiration in Portugal. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Feng, K.; Liu, J.; Fu, B. Temporal and Spatial Evolution of Meteorological Drought in Inner Mongolia Inland River Basin and Its Driving Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusza, Y.; Sanchez-Canete, E.P.; Galliard, J.L.; Ferriere, R.; Chollet, S.; Massol, F.; Hansart, A.; Juarez, S.; Dontsova, K.; Haren, J.V.; et al. Biotic soil-plant interaction processes explain most of hysteric soil CO(2) efflux response to temperature in cross-factorial mesocosm experiment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 905. [Google Scholar]

- Aishan, T.; Halik, Ü.; Cyffka, B.; Kuba, M.; Abliz, A.; Baidourela, A. Monitoring the hydrological and ecological response to water diversion in the lower reaches of the Tarim River, Northwest China. Quat. Int. 2013, 311, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y. Assessing the effect of EWDP on vegetation restoration by remote sensing in the lower reaches of Tarim River. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 74, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Ma, X.; Huo, T.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, C. Assessment of the environmental effects of ecological water conveyance over 31 years for a terminal lake in Central Asia. Catena 2022, 208, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, P.; Yan, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Chen, H. Plant Phenology and Its Anthropogenic and Natural Influencing Factors in Densely Populated Areas During the Economic Transition Period of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 792918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Luo, Y.; Yang, S.; Lu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, M.; Shi, C.; Liao, M. Change trend and sustainability of vegetation net primary productivity ofterrestrial ecosystems in different global climatic zones. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 3729–3743. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Li, Z.; You, X.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, C. The model estimation and sensitivity analysis of greenhouse gas on water-air interface in Pengxi River, Three Gorges Reservoir. J. Lake Sci. 2017, 29, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Deng, Q.; Duan, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, M. Dynamic monitoring and analysis of the earthquake Worst-hit area based on remote sensing. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 8691–8702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Data | Unit | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenology | SOS/EOS | Day | 0.1° | Year |

| Terrain | GDEMV3 | m | 30 m | N/A |

| Climate | 2 m temperature (T2M) | K | 0.1° | Month |

| Evaporation from vegetation transpiration (E) | M of water equivalent | 0.1° | Month | |

| 10 m component of wind (10 M GRD) | m s−1 | 0.1° | Month | |

| Total precipitation (TP) | m | 0.1° | Month | |

| Soil temperature (ST) | K | 0.1° | Month | |

| Volumetric soil water layer (SW) | m3 m−3 | 0.1° | Month | |

| Drought | SPI | N/A | 0.1° | Year |

| SPEI | N/A | 0.1° | Year | |

| PDSI | N/A | 0.1° | Year | |

| EDDI | N/A | 0.1° | Year |

| Slope | Significance Level | Change Trend |

|---|---|---|

| S > 0 | Z > 1.96 | Significantly Improved |

| 0 < Z < 1.96 | Slightly Improved | |

| 0.05 < Z | Stable | |

| S < 0 | 0 < Z < 1.96 | Slightly Degenerated |

| Z > 1.96 | Significantly Degenerated |

| CV | Level of Stability |

|---|---|

| CV ≤ 0.10 | High Stability |

| 0.10 < CV ≤ 0.15 | Middle High Stability |

| 0.15 < CV ≤ 0.20 | Middle Stability |

| 0.20 < CV ≤ 0.30 | Low Stability |

| 0.30 < CV | Extremely Low Stability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, J.; Feng, Y.; Yan, D.; Yu, K. Multi-Decadal Vegetation Phenology Dynamics in China’s Arid Northwest: Unraveling Climate–Terrain Interactions via PLS-SEM. Land 2026, 15, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010061

Zhu J, Feng Y, Yan D, Yu K. Multi-Decadal Vegetation Phenology Dynamics in China’s Arid Northwest: Unraveling Climate–Terrain Interactions via PLS-SEM. Land. 2026; 15(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Junxiang, Yuqing Feng, Dezhao Yan, and Kaining Yu. 2026. "Multi-Decadal Vegetation Phenology Dynamics in China’s Arid Northwest: Unraveling Climate–Terrain Interactions via PLS-SEM" Land 15, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010061

APA StyleZhu, J., Feng, Y., Yan, D., & Yu, K. (2026). Multi-Decadal Vegetation Phenology Dynamics in China’s Arid Northwest: Unraveling Climate–Terrain Interactions via PLS-SEM. Land, 15(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010061