Multifaceted Adaptive Strategies of Alternanthera philoxeroides in Response to Soil Copper Contamination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Treatment

2.2. Plant Pre-Cultivation and Treatment

2.3. Growth Measurements

2.4. Copper Content Measurements

2.5. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity, MDA, and Soluble Sugar Measurements

2.6. Chlorophyll, Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters, and Photosynthesis Measurements

2.7. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

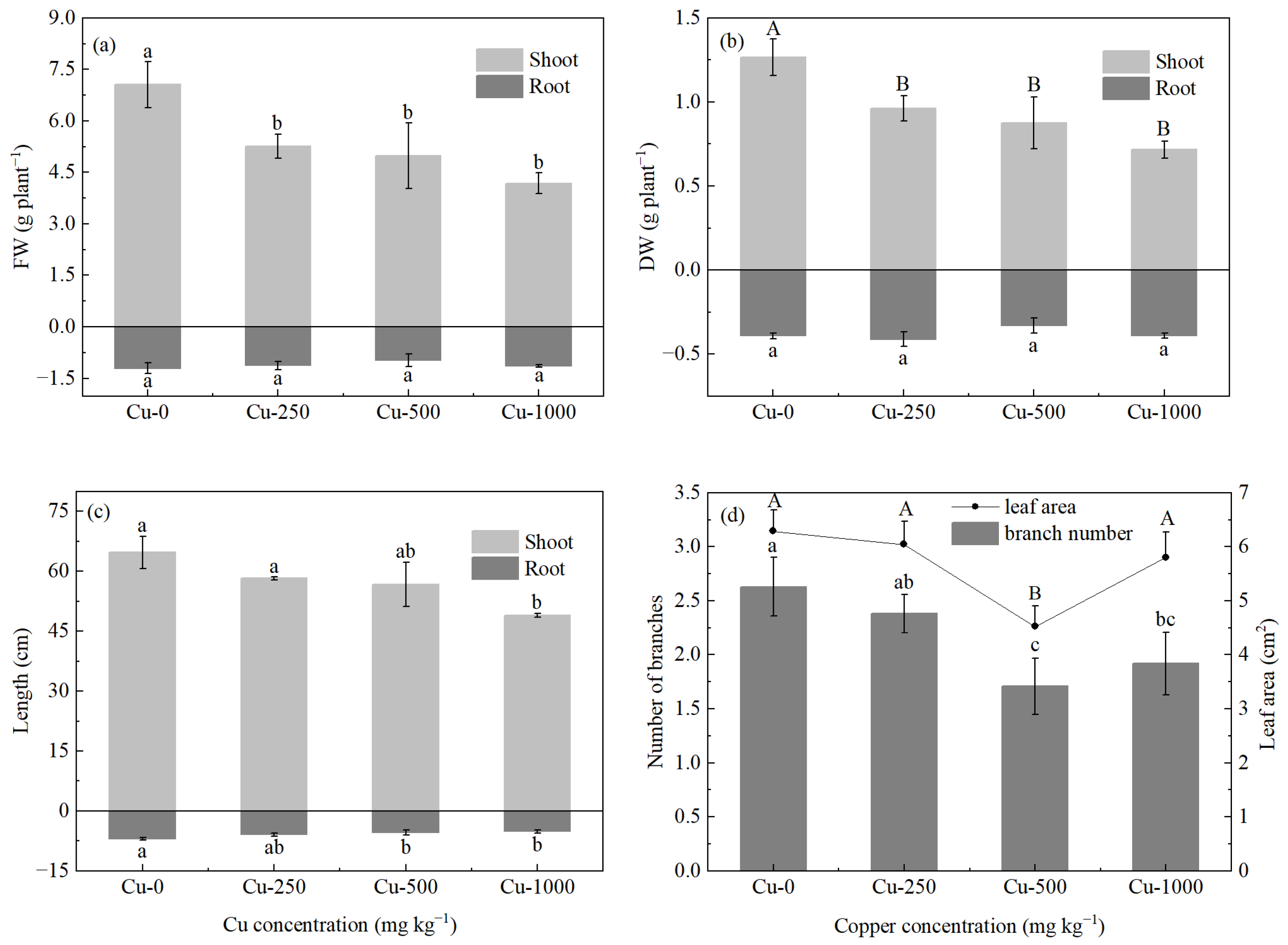

3.1. Effects of Copper on Plant Growth and Tolerance Index

3.2. Effect of Copper on Plant Copper Content and Transfer Coefficient

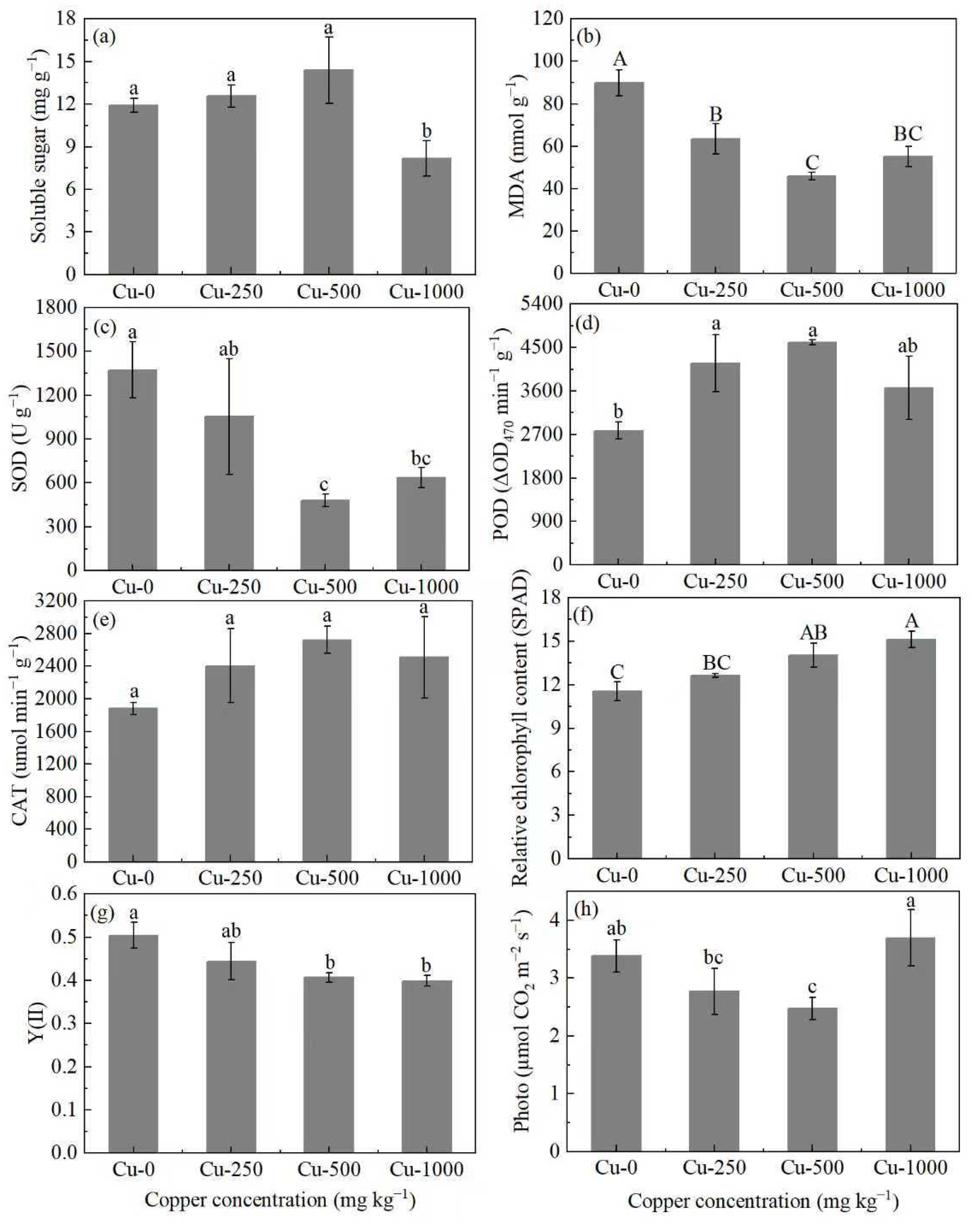

3.3. Effect of Copper on Soluble Sugar, MDA, Antioxidant Enzyme, and Photosynthetic Progress

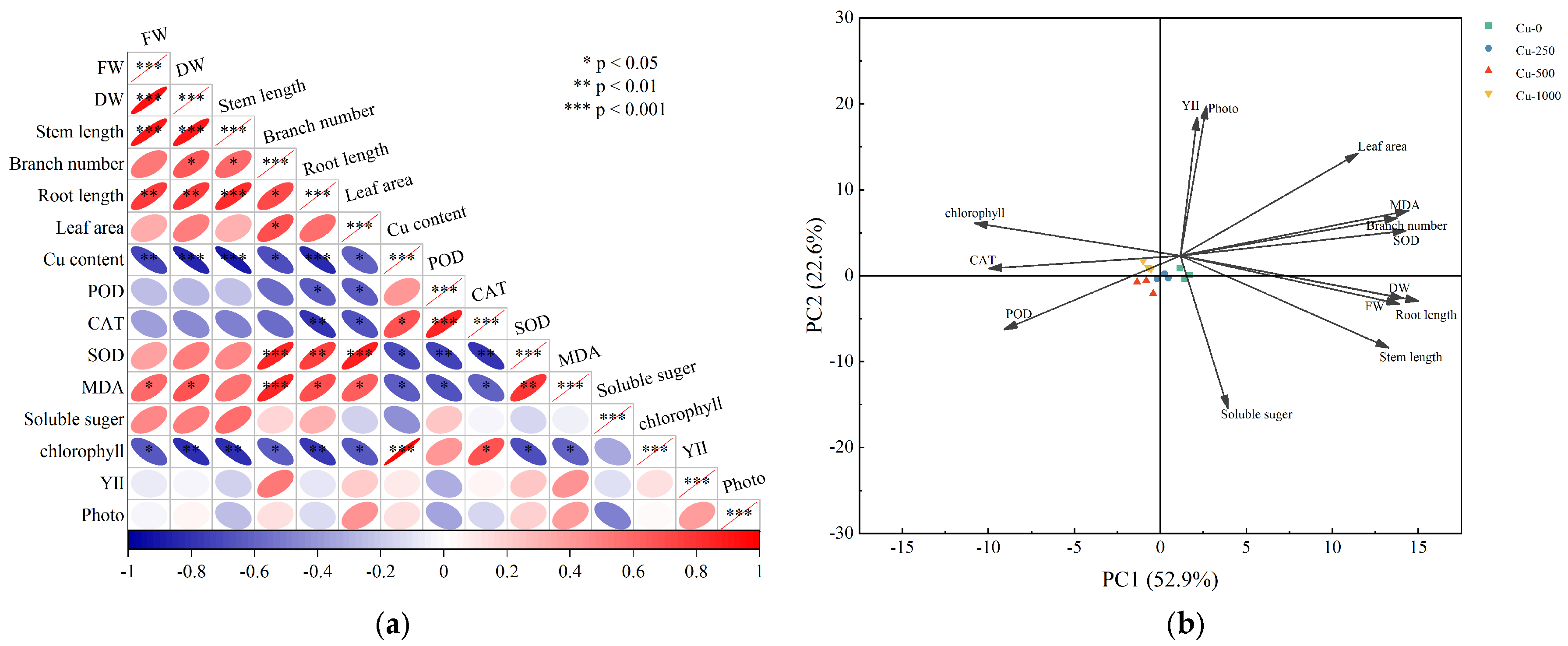

3.4. Correlation of Physiological and Biochemical Indexes Under Copper Treatment

4. Discussion

4.1. Tolerance Strategies of A. philoxeroides in Response to Copper Stress

4.2. Diffusive Escape Strategy of A. philoxeroides in Response to High Copper Stress

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brun, L.A.; Maillet, J.; Hinsinger, P. Evaluation of copper availability to plants in copper-contaminated vineyard soils. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 111, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Q.; Lee, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, H. Distribution of heavy metal pollution in surface soil samples in China: A graphical review. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 97, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China. Q&A for Nationwide Soil Pollution Survey Report; MEP: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Li, Z.Y.; Ma, Z.W.; van der Kuijp, T.J.; Yuan, Z.W.; Huang, L. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from mines in china: Pollution and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468–469, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.Y.; Sun, H.F.; Chen, D.L. Accumulation and distribution of heavy metals in dominant plants growing on Tonglushan mineral areas in Hubei Province, China. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2008, 03, 436–439. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Muyumba, D.K.; Liénard, A.; Mahy, G.; Luhembwe, M.N.; Colinet, G. Characterization of soil-plant systems in the hills of the copper belt in katanga. A review. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2015, 19, 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Ye, Z.; Wong, M. Lead and zinc accumulation and tolerance in populations of six wetland plants. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 141, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, J.Z.; Liu, M.; Yan, Z.Q.; Xu, X.L.; Kuzyakov, Y. Invasive plant competitivity is mediated by nitrogen use strategies and rhizosphere microbiome. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, K.; Li, J.; Anandkumar, A.; Leng, Z.; Zou, C.B.; Du, D. Managing environmental contamination through phytoremediation by invasive plants: A review. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 138, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiong, Y.T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.J. Combination effects of heavy metal and inter-specific competition on the invasiveness of Alternanthera philoxeroides. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 189, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q. Long period exposure to serious cadmium pollution benefits an invasive plant (Alternanthera philoxeroides) competing with its native congener (Alternanthera sessilis). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telesnicki, M.C.; Sosa, A.J.; Greizerstein, E.; Julien, M.H. Cytogenetic effect of Alternanthera philoxeroides (alligator weed) on Agasicles hygrophila (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in its native range. Biol. Control 2011, 57, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Hua, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Effects of simulated acid rain on rhizosphere microorganisms of invasive Alternanthera philoxeroides and native Alternanthera sessilis. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 993147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longstreth, D.J.; Burow, G.B.; Yu, G. Solutes involved in osmotic adjustment to increasing salinity in suspension cells of Alternanthera philoxeroides Griseb. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2004, 78, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.M.; Rizvi, S.A. Accumulation of chromium and copper in three different soils and bioaccumulation in an aquatic plant, Alternanthera philoxeroides. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2000, 65, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.P.; Pan, X.Y.; Xu, C.Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Li, B.; Chen, J.K.; Lu, B.R.; Song, Z.P. Phenotypic plasticity rather than locally adapted ecotypes allows the invasive alligator weed to colonize a wide range of habitats. Biol. Invasions 2007, 9, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhou, F.; Pan, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.J.; Li, B. Effects of soil nitrogen levels on growth and defense of the native and introduced genotypes of alligator weed. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 3, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Siemann, E.; He, M.; Wei, H.; Shao, X.; Ding, J. Climate warming increases biological control agent impact on a non-target species. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, Y.; Ren, K.; Zhang, Y. Absorption characteristics of compound heavy metals vanadium, chromium, and cadmium in water by emergent macrophytes and its combinations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 17820–17829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.Z.; Shi, G.X.; Xu, Y.; Hu, J.Z.; Xu, Q.S. Physiological responses of Alternanthera philoxeroides (mart.) griseb leaves to cadmium stress. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 147, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G.; Zhang, R.; Qian, Z.H.; Qiu, S.Y.; He, X.G.; Wang, S.J.; Si, C. Effects of cadmium and nutrients on the growth of the invasive plant Alternanthera philoxeroides. Folia Geobot. 2022, 57, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.Y.; Xu, H.F.; Zhang, W.Z.; Hou, H.J.; Qin, H.L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.M.; Fang, Y.; Wei, W.X.; Sheng, R. The characteristics of the community structure of typical nitrous oxide-reducing denitrifiers in agricultural soils derived from different parent materials. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, L.; Dai, T.W.; Zhou, J.Y.; Kang, Q.; Chen, H.B.; Li, Z.H. Effects of copper on the growth, antioxidant enzymes and photosynthesis of spinach seedlings. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Branicky, R.; Noë, A.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, D.A. The measurement of tolerance to edaphic factors by means of roots growth. New Phytol. 1978, 80, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, C.; Ray, J.G. Copper accumulation, localization and antioxidant response in Eclipta alba L. in relation to quantitative variation of the metal in soil. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.H.; Fahad, S.; Khan, S.U.; Ahmar, S.; Khan, M.H.U.; Rehman, M.; Maqbool, Z.; Liu, L.J. Morpho-physiological traits, gaseous exchange attributes, and phytoremediation potential of jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) grown in different concentrations of copper-contaminated soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 189, 109915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.A.; Yiwen, M.; Saleh, M.; Salleh, M.N.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Giap, S.G.E.; Chinni, S.V.; Gobinath, R. Bioaccumulation and Translocation of Heavy Metals in Paddy (Oryza sativa L.) and Soil in Different Land Use Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.W.; Qi, C.M.; Wang, Z.C.; Ouyang, C.B.; Li, Y.; Yan, D.D.; Wang, Q.X.; Guo, M.X.; Yuan, Z.H.; He, F.L. Biochemical and ultrastructural changes induced by lead and cadmium to crofton weed (Eupatorium adenophorum Spreng.). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 12, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.Q.; Yu, S.; Bañuelos, G.S.; He, Y.F. Accumulation of Cr, Cd, Pb, Cu, and Zn by plants in tanning sludge storage sites: Opportunities for contamination bioindication and phytoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 22477–22487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, H.X.; Wang, A.; Min, L.; Shen, Z.G.; Lian, C.L. Phenotypic plasticity accounts for most of the variation in leaf manganese concentrations in Phytolacca americana growing in manganese-contaminated environments. Plant Soil 2015, 396, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestri, E.; Marmiroli, M.; Visioli, G.; Marmiroli, N. Metal tolerance and hyperaccumulation: Costs and trade-offs between traits and environment. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 68, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, G.J. Phenotypic Plasticity: Beyond Nature and Nurture. Heredity 2002, 89, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, T.F.; Liu, C.X.; Luo, F.L. The Invasive Wetland Plant Alternanthera philoxeroides Shows a Higher Tolerance to Waterlogging than Its Native Congener Alternanthera sessilis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Ma, F. Responses of Phragmites australis to copper stress: A combined analysis of plant morphology, physiology and proteomics. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Yin, L.Y.; Zhang, Q.F.; Wang, W.B. Effect of Pb toxicity on leaf growth, antioxidant enzyme activities, and photosynthesis in cuttings and seedlings of Jatropha curcas L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, P.; Charest, C. Allocation plasticity and plant-metal partitioning: Meta-analytical perspectives in phytoremediation. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 156, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.R.; Pichtel, J.; Hayat, S. Copper: Uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants and management of Cu-contaminated soil. Biometals 2021, 34, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, H.; Jouili, H.; Geitmann, A.; Ferjani, E.E. Cell wall accumulation of Cu ions and modulation of lignifying enzymes in primary leaves of bean seedlings exposed to excess copper. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010, 139, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrollé, J.; Mateos-Naranjo, E.; Redondo-Gómez, S.; Luque, T.; Figueroa, M.E. Growth, reproductive and photosynthetic responses to copper in the yellow-horned poppy, Glaucium flavum Crantz. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 71, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, H.; Jouili, H.; Geitmann, A.; Ferjani, E.E. Structural changes of cell wall and lignifying enzymes modulations in bean roots in response to copper stress. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010, 136, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, S.V.; Israr, M.; Srivastava, A.K.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L.; Parsons, J.G. Accumulation, speciation and cellular localization of copper in Sesbania drummondii. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 2257–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzeslowska, M. The cell wall in plant cell response to trace metals: Polysaccharide remodeling and its role in defense strategy. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzesłowska, M.; Rabęda, I.; Basińska, A.; Lewandowski, M.; Mellerowicz, E.J.; Napieralska, A.; Samardakiewicz, S.; Woźny, A. Pectinous cell wall thickenings formation—A common defense strategy of plants to cope with lead. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.M.; Liu, W.C.; Jin, Y.; Lu, Y.T. Role of ROS and auxin in plant response to metal-mediated stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e24671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Niyogi, K.K. Manipulation of Photoprotection to Improve Plant Photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alscher, R.G.; Erturk, N.; Heath, L.S. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadhasani, F.; Rahimi, M. Growth response and mycoremediation of heavy metals by fungus Pleurotus sp. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, M.; Bhikharie, A.V.; McLean, E.H.; Boonman, A.; Visser, E.J.W.; Schranz, M.E.; van Tienderen, P.H. Wait or escape? Contrasting submergence tolerance strategies of Rorippa amphibia, Rorippa sylvestris and their hybrid. Ann. Bot. 2012, 7, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.F.; Zhang, X.P.; Niu, H.G.; Lin, F.; Ayi, Q.L.; Wan, B.N.; Ren, X.Y.; Su, X.L.; Shi, S.H.; Liu, S.P.; et al. Differential Growth Responses of Alternanthera philoxeroides as Affected by Submergence Depths. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 13, 883800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.L.; Thiele, B.; Janzik, I.; Zeng, B.; Schurr, U.; Matsubara, S. De-submergence responses of antioxidative defense systems in two wetland plants having escape and quiescence strategies. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 17, 1680–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hu, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, C.; Yu, D. Tolerance and resistance facilitate the invasion success of Alternanthera philoxeroides in disturbed habitats: A reconsideration of the disturbance hypothesis in the light of phenotypic variation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 153, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | RBR | SMR | LMR | Root Shoot Ratio | TI (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW | DW | SL | RL | |||||

| Cu-0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 c | 0.6 ± 0.0 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 c | / | / | / | / |

| Cu-250 | 0.3 ± 0.0 b | 0.6 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 77.3 | 82.9 | 90.0 | 84.4 |

| Cu-500 | 0.3 ± 0.0 b | 0.6 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 72.2 | 72.7 | 87.6 | 76.9 |

| Cu-1000 | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.5 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 64.4 | 66.7 | 75.6 | 73.3 |

| Treatment | Copper Concentration (mg kg−1) | TFroot→shoot | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root | Stem | Leaf | ||

| Cu-0 | 27.7 ± 4.4 D | 37.3 ± 9.9 a | 29.9 ± 1.8 C | 1.37 a |

| Cu-250 | 81.2 ± 15.1 C | 38.8 ± 6.0 a | 48.5 ± 2.9 BC | 0.51 b |

| Cu-500 | 178.0 ± 7.2 B | 64.9 ± 8.3 a | 62.3 ± 3.4 AB | 0.36 b |

| Cu-1000 | 264.5 ± 20.0 A | 69.7 ± 20.8 a | 77.1 ± 14.9 A | 0.27 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Li, K.; Huang, X.; Xin, X.; Wright, A.; Li, Z.; Zhao, L. Multifaceted Adaptive Strategies of Alternanthera philoxeroides in Response to Soil Copper Contamination. Land 2026, 15, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010031

Wang L, Li K, Huang X, Xin X, Wright A, Li Z, Zhao L. Multifaceted Adaptive Strategies of Alternanthera philoxeroides in Response to Soil Copper Contamination. Land. 2026; 15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ling, Kun Li, Xun Huang, Xiaoping Xin, Alan Wright, Zhaohua Li, and Liya Zhao. 2026. "Multifaceted Adaptive Strategies of Alternanthera philoxeroides in Response to Soil Copper Contamination" Land 15, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010031

APA StyleWang, L., Li, K., Huang, X., Xin, X., Wright, A., Li, Z., & Zhao, L. (2026). Multifaceted Adaptive Strategies of Alternanthera philoxeroides in Response to Soil Copper Contamination. Land, 15(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010031