1. Introduction

The practice of integrating a gender perspective into urban analysis and planning is increasingly being recognised for its usefulness as an evaluative tool and for its potential to provide a foundational framework for strategies aimed at achieving spatial justice and improving care-related mobility [

1]. Incorporating this perspective has allowed for the introduction of new paradigms and conceptual frameworks, with feminist urbanism emerging as a central axis.

Our bibliometric research on gender equality, urbanism, and sustainability identified only a limited body of academic work that integrates all three of these dimensions, with the most prominent areas of study including environmental studies, green technologies, business, and gender studies. The gender perspective has become a common thread in research into diversity, corporate and environmental sustainability, governance, and community development. Policies such as gender mainstreaming, for example—aligned with SDGs 5 and 11, as well as several other EU and UN strategies—are notable for their role in combating discrimination in urban spaces and strengthening sustainable development [

2], while ecofeminism has emerged as a valuable approach to planning more inclusive urban environments, prioritising feminist epistemologies and adopting a political stance that challenges the perception of gender issues as isolated niches.

According to Henri Lefebvre [

3], it is essential to continue to build a methodological framework that recognises the everyday lives of women as a situated political experience. Furthermore, expanding the traditional analytical framework to incorporate gender-sensitive dimensions allows us to identify the tensions between spatial practices, power relations, and territorial transformation processes [

4]. By centring gender as a critical analytical lens for evaluating space and urban governance, we can gain a deeper understanding of how it influences urban practices [

5]. From this perspective, the study of violence and care, for instance, may contribute to the construction of new interpretative, theoretical, and prospective paradigms for urban development.

In addition to reviewing the theoretical framework, we must also utilise practical instruments such as manuals and publications, which serve as useful tools for the critical assessment of public spaces and buildings. These resources highlight aspects such as safety, vitality, dynamism, connectivity, and legibility, ranging from strategic planning approaches that incorporate gender-sensitive criteria into comprehensive regeneration initiatives at the urban or regional scale [

6,

7] to the specification of parameters such as tenure regimes and the presence or absence of public protection in housing development. Some manuals focus specifically on the building and housing scale [

8], while others, adopting an inter-scale perspective, propose interventions articulated through strategic lines that encompass multiple spatial levels: housing, building, and the immediate surroundings [

9].

The goal of many of the texts and materials reviewed is to redirect policies towards a more equitable and inclusive vision of urban and residential environments. Feminist critique adds another level to the analyses of public and private spaces, which have historically produced urban and domestic designs that separate areas dedicated to labour from those associated with care. This approach highlights the fact that the management of urban and domestic spaces often reflects strategies of control and oppression that are geared towards marginalisation and the perpetuation of patriarchal and capitalist systems of domination [

10]. Since 1976, and most recently in 2016, the documents issued by the successive Habitat program conferences have developed a series of recommendations that can be used as specific indicators for assessing the degree of gender mainstreaming in urban planning policies. These studies aim to advance toward the concept of “reconciling cities” [

11] by responding to the specific needs of women—including those associated with their role as caregivers—to ensure equitable access to the city [

12].

Although legislation may not always be effectively implemented, it is possible to actively reflect on the direction that future legislative initiatives should consciously pursue. In Spain, for example, significant steps forward were achieved with Organic Law 3/2007 [

13] and Law 11/2018 [

14], which integrate the gender perspective into governance. However, legislative action must be complemented by other relevant instruments outlined in their implementing regulations [

15,

16]. The existence of gender-focused laws and regulations allows for a revaluation of urban policies, recognising their transformative potential in territorial planning [

17].

To understand urban dynamics from a care-centred perspective, numerous methodologies and tools have been developed that utilise diverse techniques to evaluate urban environments. Tools based on systematic observation provide valuable information on key aspects of public spaces, reaffirming the persistence of traditional social roles [

18]. Moreover, observational methods can reveal the specific conditions faced by users of the urban fabric, particularly those facing challenging circumstances [

19].

Observational techniques can be complemented by qualitative tools such as collective mapping experiences, workshops, and interviews, which allow for the assessment of the various activities and practices of dissident groups in public space—often carried out in a constant state of alert, which is largely shaped by the perception of insecurity in the area [

20]. In addition, social cartographies can highlight new forms of territorial representation and documentation. All of these analytical tools generate transversal and situated information, contributing to urban planning as a collective practice [

3].

Viewing urban studies through a gender lens allows for classifications based on differentiated dimensions, such as proximity, autonomy, or representativeness [

21], while others—such as safety—are central and explicitly addressed in all feminist-oriented research [

22,

23]. Systematised research allows us to evaluate urban spaces using both qualitative and quantitative indicators, which can be grouped into complementary dimensions that can further our understanding of not only the characteristics of a given space but also the conflicts and dynamics that emerge within it.

The purpose of this article is to describe the design of a replicable and scalable evaluation tool that can be used to promote equality, inclusivity, and accessibility in the design and analysis of habitable spaces in urban and domestic environments. The research is grounded in a multidimensional reading of urban life, approached from an inter-scale perspective and through a gender lens, understood not only as an analytical category but as a structuring principle of space. The methodological framework derived from this research establishes a cross-cutting approach that facilitates a comprehensive understanding of living spaces, allows for the identification of problems, and guides the design of integrated solutions that can be included in municipal public policies as a mechanism for creating spaces that are aligned with a gender perspective.

The tool consists of a set of indicators selected in accordance with the following fundamental principles: operability, multiscale nature, and multidimensionality. The novelty of the proposal lies in its approach to urban analysis, which allows for a complex understanding of citizen dynamics, taking into account different scales of approximation and approaches. For this reason, the indicators have been selected according to the following criteria: they should provide comprehensive coverage of the different dimensions of everyday life, such as commuting to work, movements associated with caregiving, and domestic activities. Considering both these premises and the compilation of indicators identified in the consulted bibliography, we added some additional indicators that had not previously been considered, such as informal surveillance and care of public spaces, different mobility options, and the mix of uses and activities. In addition, and on a more limited scale, the existence of activities in common spaces, the various building typologies and building energy efficiency.

In the domestic dimension, aspects such as the convenience of the laundry cycle and the flexibility of circulation spaces have been incorporated. The main objective of the tool is to enable its operational application in the design and construction of egalitarian, inclusive, and accessible spaces at the three scales that make up cities—neighbourhood, interblock, and housing—thus allowing for aspects specific to each scale to be distilled, which, in turn, may complement each other.

In the multiscale analysis, safety, visibility, and surveillance are priorities at the neighbourhood scale and reappear at the inter-block scale, along with vitality and social diversity, applied to spaces close to buildings. Identity and representativeness are limited to broad urban areas, while accessibility remains a cross-cutting dimension at all scales, guaranteeing minimum conditions of habitability. At the inter-block scale, the mix of uses and activities and the care of public space stand out, incorporating critical areas such as circulation and parking, which are also present at the housing scale. The latter emphasises specific interior spaces linked to domestic tasks—laundry, cooking, storage, and work—which are recurrent in the literature consulted. The study reveals how each scale prioritises different attributes, although the accessibility and functionality of a space emerge as common principles for urban and residential quality.

The tool has been specifically designed for use in the urban fabric representative of modern developmentalism that can be found in cities all over the world: the open-block typology. Given the spatial complexity and urban dynamics of this context, we compiled a broad and diverse catalogue of parameters that can also be applied to other urban environments with minimal adaptation.

The guiding hypothesis of this study asserts that urban, intermediate, and domestic spaces have historically been designed by and for heterosexual, white, able-bodied men, resulting in exclusionary environments that fail to reflect the diversity of bodies, identities, and ways of life that inhabit cities. Consequently, by incorporating a gender perspective into the design and evaluation of these spaces, we can plan inclusive environments that acknowledge this diversity and provide for the well-being and care of all individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

The research method developed for the creation of this multidimensional tool for the inter-scale analysis of neighbourhoods, inter-block spaces, and housing units from a gender perspective was structured into six stages: (1) Literature review and state-of-the-art analysis; (2) Definition of scales of approach; (3) Formulation of indicators; (4) Establishment of the evaluation scale; (5) Design of data collection instruments; and (6) Adjustment of the analysis and evaluation tool.

2.1. Literature Review and State-of-the-Art Analysis

The literature review provided much of the necessary information for developing indicators to assess whether the spaces under study were aligned with a gender perspective. Existing indicators and analytical parameters were identified in manuals, books, and regulations. Initially, the review aimed to compile the broadest possible set of analytical parameters, which were later refined to include both those explicitly classified by their authors as gender-related and others that, despite not being originally intended for gender-based analysis, could acquire that quality within the framework of this study.

The book “Gender space architecture. An Interdisciplinary Introduction” [

24] proposes an architectural analysis based on the social dimension of buildings, as sets of servant spaces, to facilitate the daily life of their residents. The indicators compiled in the manual refer, above all, to the building scale and housing cell, delving into aspects related to domestic tasks and also on the flexibility and non-hierarchization of the rooms.

The concepts of flexibility and gender equality are also developed in the article “Flexibility and gender equality in housing” [

25], which explains how greater versatility of spaces can be promoted through specific measures in housing design. In this way, it deals with issues such as the minimum dimensions of rooms, kitchens, bathrooms or terraces, as well as the relationship between them and the arrangement of the furniture inside. The analysis of twenty examples of housing assesses how the distribution of spaces, their proportions and their dimensions can provide less hierarchical and more flexible spaces.

Other aspects of a more subjective nature and not linked to formal aspects, such as acoustic comfort, respect for rest or the enjoyment of play, are reviewed as indicators of well-being in the book “The City of Care” [

26], a publication that makes visible the caring possibilities of cities through their most basic elements such as a bench, a fountain or a shadow.

The revision of the book “Reconfiguring the Urban Space: Gender Perspectives in Urban Housing” [

27,

28] as “Architecture with Architects” has served to incorporate indicators related to visibility, surveillance, orientation and others on the interior functionalities of the home.

On the other hand, the manuals of good practices in urban planning and housing, which are understood as useful tools for the critical review of public spaces and buildings, highlight aspects such as safety, vitality, dynamism, connectivity or legibility.

The study of the manual “Designing the spaces of everyday life” [

8] focuses on the scale of the building and the home, being very specific in terms of the quality of the spaces and their practicality, especially in design aspects such as materials, communication cores (lifts and stairs), lighting, spaces for collective use, the laundry cycle, cooking space, storage, work and study spaces, the flexibility of rooms or bathrooms.

The neighbourhood scale has been addressed for the selection of structural indicators, such as those related to urban policies, which appear in the “Guide to incorporating the gender perspective in urban actions in the Valencian Community” [

7], from which parameters such as the tenure regime and the existence or not of public protection in housing development are extracted. In this same text, attention is also paid to more qualitative aspects of urban space at the interblock and neighbourhood scale, such as the care, orientation and level of traffic of common spaces or the activity and diversity of commerce. Some good Urban Regeneration policies, such as the dimensions of pedestrian spaces and favouring school paths, are incorporated from the text “Urban Regeneration with a Gender Perspective within the framework of the Urban Agenda of the Basque Country” [

6], which also presents a strategic point of view on how to incorporate the gender perspective in comprehensive regeneration actions.

Finally, with a feminist perspective, reflections on the representativeness of all groups and individuals, as well as the existence of identity, are incorporated as essential qualitative indicators, some of which are collected from the document “Feminist Urbanism for a Radical Transformation of Living Spaces” [

9].

To complete the consultation, regulatory documents have been examined in order to ensure compliance with certain minimum requirements of the Technical Building Code, mainly with regard to safety of use and accessibility (DB-SUA) and fire protection (DB-SI), and to guarantee accessibility through the proceedings of Royal Decree 193/2023 [

29], of 21 March, which regulates the basic conditions of accessibility and non-discrimination of people with disabilities for access to and use of goods and services available to the public and the DALCO criteria, set out in the UNE 170001-1.2007 standard (part 1) [

30].

2.2. Definition of Scales of Approach

The consultation of the text “The city of citizens” [

31] allowed us to define and delimit each of the scales, as well as to establish boundaries, similarities, and differences between them.

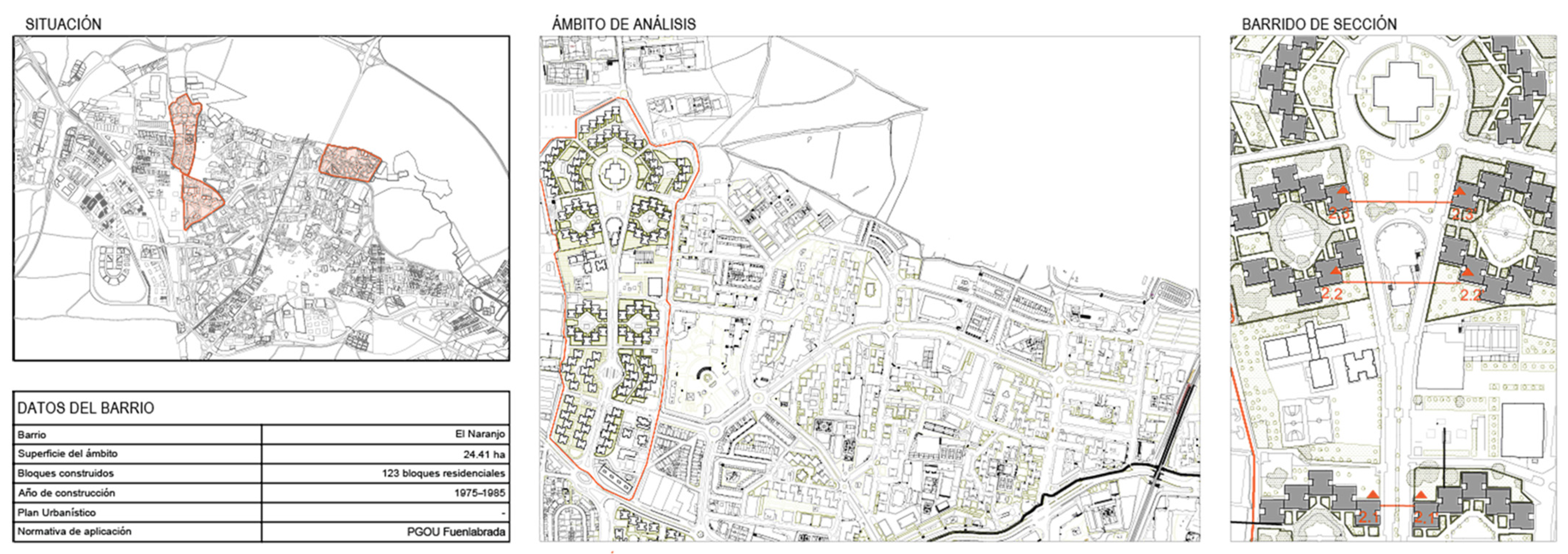

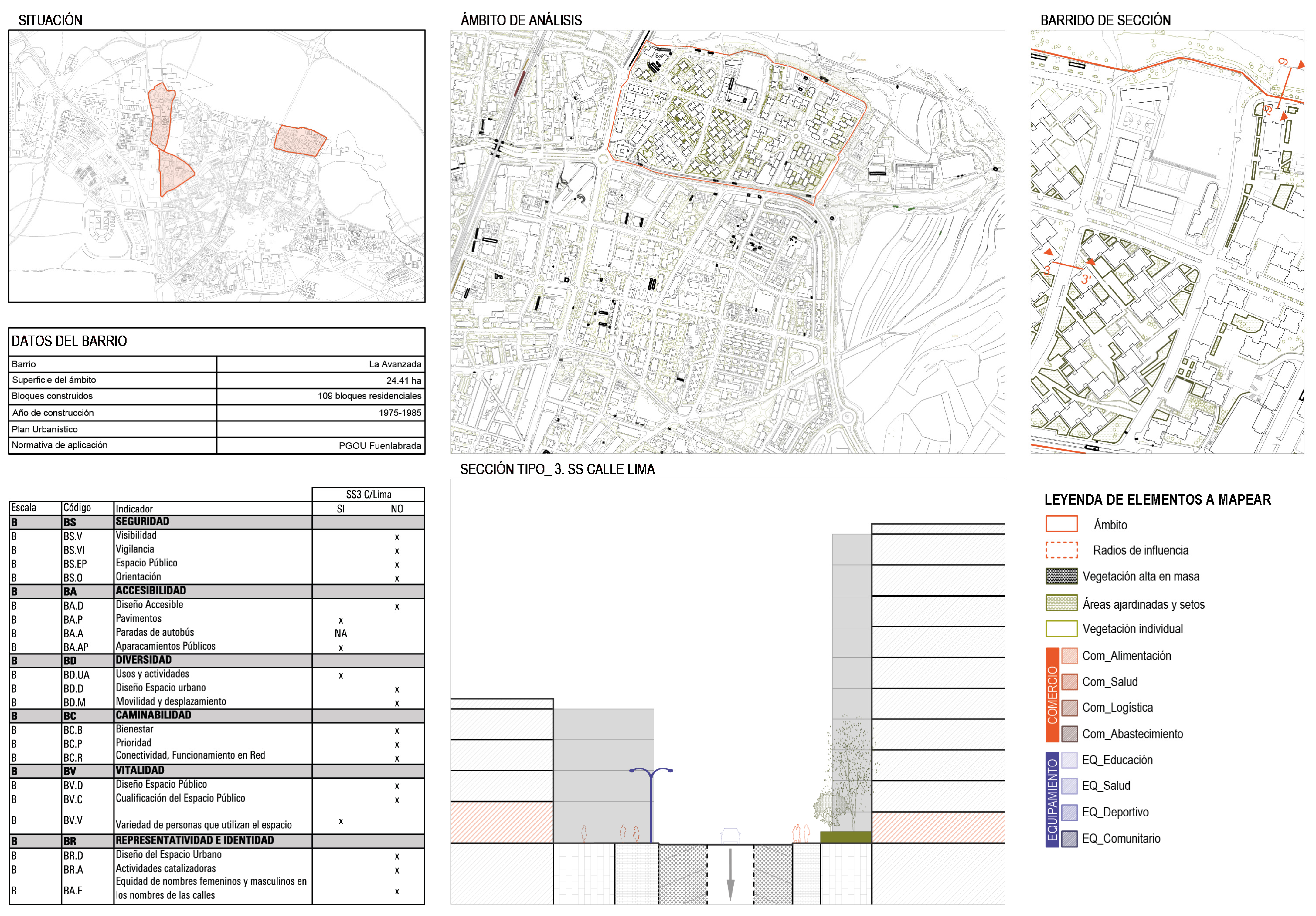

The neighbourhood scale was oriented toward understanding urban areas with a strong local identity and the presence of essential services such as schools, health centres, markets, parks, and public transportation. In defining the boundaries of this scale, a basic criterion was applied: the selected areas had to have a manageable geographic extension, typically zones that could be walked across in approximately 10 to 15 min, corresponding to distances of around 800 to 1000 m (

Figure 1A).

The inter-block scale focused on understanding accessibility and citizen well-being in the immediate surroundings of residential buildings. The specific objective of this scale was to analyse the functioning of the context closest to the home, where people interact daily, considering not only spatial qualities but also the use and enjoyment of public and private spaces and how these affect different social groups—particularly women, older adults, children, and other minorities traditionally excluded from urban design (

Figure 1B).

The housing scale analysis is centred on accessibility, care, spatial hierarchies, and flexibility. The specific objective of this scale was to understand the functioning of the domestic space, taking into account not only the housing unit itself but also the collective spaces within the buildings. As with the previous scales, the housing scale analysis aimed to adopt a comprehensive approach that ensured the evaluation of both the functionality of these spaces and their impact on social cohesion and equity, addressing the diverse needs of the population. The analysis was structured into two main sections: on the one hand, an evaluation of the housing block from the perspective of shared spaces; and on the other, an assessment of the housing unit, which included its spatial configuration, installations, and construction (

Figure 1C).

2.3. Formulation of Indicators

Based on the literature review and state-of-the-art analysis, we developed an initial set of indicators to evaluate spaces from an inclusive and feminist perspective. These indicators, grouped into categories, enabled a segmented assessment by scale, allowing for the evaluation of whether a space had been configured in alignment with gender-sensitive criteria.

The literature review allowed us to define six cross-cutting dimensions for organising the indicators: safety, vitality, accessibility, representativeness and identity, diversity, and walkability. Eight complementary dimensions were added to qualify each scale: complementary utilities, tenure, flexibility and hierarchy, adaptability, energy efficiency, stays, facilities and construction, and noise. These dimensions form a comprehensive framework for evaluating habitability and spatial quality, considering how design affects everyday lived experiences, especially for women.

Safety was addressed through four aspects: visibility, care of common space, orientation, and surveillance. Lighting, visual control between access points and dwellings, maintenance, signage, and the existence of formal and informal supervision mechanisms were analysed. Vitality was evaluated in relation to the space’s capacity to promote socialisation, emotional well-being, and intergenerational coexistence, ensuring inclusion for different social profiles. Accessibility was examined from the perspective of mobility, considering public transportation, pedestrian routes, paving, signage, ramps, elevators, and urban furniture that facilitates rest.

Identity was assessed based on the presence of elements that foster community roots and a sense of belonging. Diversity was studied through the mix of land uses, the proximity of essential resources, and the integration of leisure, work, and housing activities, as well as typological and demographic variety. Walkability was analysed based on pedestrian connectivity and infrastructure quality, including paving, shade, green areas, night lighting, and street furniture. In addition, the relationship between urban design and time management was considered, especially for women with caregiving responsibilities.

On the second level, complementary dimensions delve deeper into specific aspects. Utilities include common spaces for gathering and collective care, such as play areas, restrooms, and laundry rooms. Tenure analyses the property regime and conversion of uses. Flexibility and hierarchy are studied in the housing unit, focusing on neutral spaces, ease of renovation, and visual and physical connections. Adaptability refers to the ability of spaces to adjust to the needs of the elderly, dependents, and infants. Energy efficiency includes active and passive systems for energy conservation, ventilation, air conditioning, solar protection, and supports for vegetation. Rooms are reviewed in terms of functionality and reduction of spatial hierarchies, while facilities are evaluated for ease of modification. Finally, noise is considered in relation to acoustic vulnerability and compliance with schedules that favour rest.

Care was taken to ensure that the indicators were neither repetitive nor redundant, and that, given the transversal nature of the three scales of approach, no duplications occurred. To connect the three scales and organise the set of indicators, both transversal dimensions and complementary dimensions were defined to qualify each scale (

Table 1). A total of 598 indicators were compiled in this initial draft.

At the same time, guidelines were established to associate each indicator with its source (journal article, book chapter, manual, conference proceedings, etc.), which is essential for continuously reviewing its definition and scope, justifying its relevance, and anticipating how the indicator should be assessed.

2.4. Establishment of the Evaluation Scale

The indicators were formulated to yield a dichotomous response (yes/no), with an affirmative answer indicating compliance with the indicator from a gender perspective, allowing for an effective and straightforward evaluation. Additionally, the response options ‘does not exist’—for cases where the element is absent—and ‘not verified’—when compliance could not be confirmed due to external factors—were included. Throughout the process, consistency and systematic coherence across the three scales of the study were maintained to enable precise comparisons and conclusions.

2.5. Design of Data Collection Instruments

Based on the preliminary set of indicators, the data collection methods were defined: direct observation, maps, diagrams, interviews, focus groups, etc. Each indicator may be associated with one or more instruments depending on the type of information required (

Table 2).

Direct observation was the most frequently used method. The data collection process involved preparing tables compiling the indicators to be evaluated, along with blank base maps for each scale, on which the collected data could be recorded.

To obtain maps of the study are at the urban, inter-block, and housing scales, we redrew existing maps using documents sourced from municipal archives of the neighborhoods being studied, as well as geographic visualisation software. In the office, these maps were used to produce a series of analytical diagrams designed to generate data that responded to several indicators.

Following approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the institution affiliated with the project, interviews and focus groups were used to complement the information gathered through direct observation and graphic documentation. The interview questions and focus group dynamics were designed to gather information primarily related to the dimensions of security, vitality, and representativeness.

Two types of interviews were conducted, depending on the interviewees: formal, structured interviews with municipal technicians, and informal, semi-structured interviews with pedestrians who had walked through the study area.

In the participatory part of the focus groups, we asked the participants to draw on data collection graphics at the three scales of analysis (

Figure 2A) and used 3D-printed models of the housing units in their current configuration (

Figure 2B) to facilitate spatial understanding and dialogue with non-specialist populations. In cases where the focus groups included Children and Youth Councils (Group of 26 youth and children’s associations in Fuenlabrada), the data collection material was adapted to suit the tools and information that this population group could provide (

Figure 2C).

2.6. Adjustments to the Analysis and Evaluation Tool

With the draft version of the evaluation tool completed, a pilot test was conducted in a neighbourhood characterised by an open-block urban fabric. We conducted field visits, graphic documentation analysis, focus groups with local associations and interviews with residents to verify the tool’s functionality, refine the wording of the indicators, and adjust the evaluation method accordingly.

During this stage, we undertook a refinement process that included identifying and eliminating any redundant or overlapping indicators. Additionally, the indicators were reviewed and reformulated to ensure they were easy to understand and apply and yielded a dichotomous response, with an affirmative answer indicating compliance with the gender perspective. A key criterion in this adjustment was to guarantee that the indicators were measurable and that their implementation was feasible, given the available resources and data collection capacities of the research framework.

The identification of gaps in indicators across scales and dimensions led to the creation of new indicators developed specifically for this study. Once the indicators were modified, a second round of field verification was conducted in the same neighbourhood.

In total, 347 primary items and 259 secondary items were obtained, coded according to the established scales and dimensions (

Figure 3).

3. Results

The outcome of the described methodology is an evaluation tool that provides the information needed to determine whether urban, inter-block, and housing spaces are aligned with the gender perspective. This, in turn, makes it possible to identify the intervention needs in those spaces based on the priorities established by each municipality, as discussed further below. To provide a better understanding of the procedure, the process followed in the case study of three neighbourhoods in Fuenlabrada (Madrid)—El Naranjo, La Avanzada and El Molino—is outlined below. The explanation provides qualitative indications that will be useful when applying the tool in other places with similar characteristics. This is followed by a discussion of the method’s strengths and limitations.

The application of the assessment tool consists of four systematic steps that involve the integration of several instruments: (1) Understanding the context of the municipality; (2) Collecting information and preparing graphic documentation; (3) Evaluating the indicators; and (4) Analysing the evaluations.

3.1. Context

The first step is to develop an understanding of the municipality under study by analysing its territorial boundaries and historical growth, sociodemographic data, available infrastructure and services, and its economic, political, and administrative context. It is also useful to gather information about its cultural aspects and the challenges and issues it has faced throughout its history, as well as those it is currently experiencing.

The primary sources of information used in the case study included the book “Fuenlabrada Siglo XX. De un pueblo a una gran ciudad” [

33], municipal databases, annual reports from the municipality, online sources such as blogs and websites of associations and collectives, and the diagnostic report of Fuenlabrada’s Urban Agenda [

26].

To obtain the plans and historical construction data of the selected neighbourhoods, several meetings were held with municipal technicians from the Fuenlabrada Municipal Housing Institute. These meetings allowed us to access and scan the available plans and provided insights into how the city was built and evolved into its current configuration.

The neighbourhoods studied experienced exponential growth between 1967 and 1979, during a period when public administrations permitted real estate developments to proceed without proper urban planning. The overriding objective was to build affordable housing for working-class families who were moving en masse to the capital in search of employment, using Fuenlabrada as a residential area. This phenomenon led the municipality to transition from being an agricultural hub to a commuter town.

Today, these areas have become fully integrated city neighbourhoods, although they have been classified as “priority rehabilitation environments”. Despite the transformations undergone since the 1980s, their built fabric still suffers from significant deficiencies, including the use of poorly insulated materials, low construction quality, and limited comfort and accessibility conditions. These shortcomings have a greater impact on an ageing and socially vulnerable population.

3.2. Collecting Information and Preparing Graphic Documentation

During the evaluation process, it is essential to use graphic representation codes that provide clear evidence of the assessment. While these codes should be standardised to the extent possible, it is not always feasible to do so due to the geometric and conceptual differences between the scales.

3.2.1. Housing Scale

Evaluating the indicators at the housing scale involves some direct observation, but primarily relies on analysing architectural plans and other graphic resources, such as analytical diagrams. Information is also gathered through interviews with neighbourhood residents to address any indicators that cannot be assessed by other means and to corroborate the results obtained with other instruments. To ensure comprehensive and representative data collection, we recommend categorising the analysis by the different types of building entrances (portals) and housing units, thereby conducting a detailed and disaggregated diagnosis.

One of the graphic resources designed for this purpose includes analysis sheets: key sheets, portal sheets, and housing sheets (

Figure 4). The key sheets—one per neighbourhood—show the housing blocks under study, including data on the number of floors, the types of portals found in those blocks, and the types of housing units they contain. The aim of the key sheets is to provide an at-a-glance overview of the neighbourhood’s composition. The portal sheets illustrate the types of entrances identified in the housing blocks, based on municipal plans. The housing analysis sheets are designed according to the different typologies repeated within the blocks. For each housing unit, data on usable floor area, number of bedrooms, and the presence or absence of a terrace are provided, along with a diagram showing its location within the block.

3.2.2. Inter-Block Scale

At the inter-block scale, direct observation during field visits is combined with focus groups involving local women in workshops and study environments. In cases where the inter-block spaces are extensive, we recommend selecting specific areas to ensure the evaluation process is as rigorous and representative as possible. The selection of these areas ensures that the analysis reflects the intermediate spaces and the most significant elements surrounding the housing blocks within each neighbourhood.

We recommended choosing specific areas that exhibit spatial uniqueness and shared characteristics (pedestrian zones, semi-public spaces, thresholds, landscaped areas, playgrounds, nearby facilities, parking areas, etc.) (

Figure 5). The analysis of each of these areas involves a comprehensive evaluation of their components: building surroundings, green spaces, landscaped areas, playgrounds, seating areas, commercial premises (operational and non-operational), pathways connecting different zones, and designated parking areas. In these zones, both the common space and its relationship with the housing entrances must be observed, as the whole determines the quality of the urban space and its ability to foster interaction among residents and their environment, as well as the perception of safety.

The redrawing of plans and the definition of the contexts for each space are carried out using patterns, textures, and different colours to represent pavements, areas, and environments within each inter-block space. The scale of the drawings at this stage should range between 1:500 and 1:700, depending on the framing and size of the blocks within the inter-block area.

To subsequently evaluate the represented spaces, each context defined by patterns must be associated with a set of indicators that categorise and assess the plots as a whole. For example, the set of indicators located within a vegetated area bordered by shrubs applies to the entire landscaped space; the same applies to playgrounds, parking areas, or access and circulation points.

To clearly represent these indicators, we recommend using a consistent set of easily identifiable symbols and icons across the different sections. Exceptions should be made for indicators that already have widely recognised symbols, such as those for accessibility, orientation, restrooms, or specific pieces of furniture (

Figure 6).

3.2.3. Neighbourhood Scale

To evaluate the indicators at the neighbourhood scale, we use direct observation combined with an analysis of urban plans and interviews with residents during focus group sessions.

To ensure that this evaluation process is as rigorous and representative as possible, we recommend selecting several specific streets in the neighbourhoods under study. The street-based analysis should focus on the structural aspects and elements of the neighbourhood, rather than on more detailed issues related to the immediate surroundings of housing entrances. The streets are strategically selected to include three types: main streets, secondary streets, and edge streets (

Figure 7).

The iconography used should be easy to read and identify, simplifying the complexity of the concepts being analysed and providing graphic consistency across the diverse indicators evaluated in the various spaces during the data collection phase.

Analysing each of these routes involves conducting a comprehensive evaluation of their entire section., i.e., examining both the street itself and the surrounding built environment. It is essential to observe not only the street’s physical space but also its relationship with the buildings and surrounding urban fabric, as these elements together determine the quality of the urban space and the interaction between inhabitants and their environment.

The graphic documentation at the neighbourhood scale should use scales that allow for a comprehensive reading of each neighbourhood. The area of analysis must be defined by its perimeter and use the following scales: 1:50,000 to represent the relationship between the three levels—neighbourhood, inter-block, and housing—within the municipality of Fuenlabrada; 1:10,000 to understand the neighbourhood and its immediate context; and 1:5000 for the typical sections used to scan the street and evaluate the indicators. Street sections are drawn at a scale of 1:500. Graphic decisions must facilitate an immediate understanding of each street section. Ideally, a simple drawing style should be chosen, supported by a legend and tables containing the analysed indicators (

Figure 8).

3.3. Focus Groups

To organise focus groups, we recommend contacting municipal technicians to obtain a list of associations, particularly those related to the neighbourhoods in the case study. Once these associations have been contacted, focus group sessions should be arranged with prepared data-collection dynamics. We also recommend reaching out to groups related to children and older adults.

During the Fuenlabrada case study, three data collection sessions were held: two at the university itself and one at the El Naranjo Neighbourhood Association. Additionally, a session was organised with the Fuenlabrada Children’s Council, with two age-adapted dynamics for the participating groups: primary education and secondary education. Children aged 6 to 12 were asked to draw pictures of their neighbourhoods and housing. For children aged 12 to 16, we used the same dynamic used with the adults to gather neighbourhood-related information. The results from both the adult and the children’s focus groups provided a wealth of essential information for evaluating indicators relating to the dimensions of safety, vitality, and representativeness, which would not otherwise have been accessible. The validation of the indicators occurred with the contrast between the documentation prepared from the consulted literature and its application to the 3 case studies of open block neighborhoods considered. The qualitative methodology of consultation with citizens was carried out with three main tools, the structured interview with municipal technicians and representatives of neighbors and focus groups, which were developed with neighbors to learn about their life dynamics. To do this, they worked on diagrams that were completed with the information provided by each neighbor. Based on the contrast of the information collected, the previously defined indicators were completed and refined.

3.4. Evaluating the Indicators

Once all data has been collected and organised, the indicators are evaluated using the scale “Yes/No/Not applicable/Does not exist”. Since representative areas of analysis are established at all three scales, the evaluation process they undergo is similar. First, each area is assessed independently, providing graphic evidence and quantitative dimensions whenever necessary. Next, areas within the same neighbourhood are compared. Finally, all the neighbourhoods included in the study are compared. This approach ensures result traceability while also allowing for partial findings.

The criterion for the overall assessment of an indicator (after assessing its area, neighbourhood, and the whole study) is that if action is required in more than one area or neighbourhood, it does not meet the gender perspective. This is because the tool aims to identify issues that require intervention, even if they have been resolved in some areas or neighbourhoods (

Table 3).

Analysing the Evaluations

As previously explained, there are level 1 indicators and level 2 sub-indicators, grouped by dimensions. This classification stems from the heterogeneity of urban and domestic spaces, as well as the decision to formulate the indicators in positive terms and in relation to compliance with the gender perspective. This also means that not all indicators and sub-indicators can be assessed using a simple one-point-per-compliance method; instead, a scoring system was established for each of the five cases listed in the indicator set.

Type a indicators are evaluated by assigning one point to the indicator itself, as they are level 1 indicators and do not have associated sub-indicators. These are cases where compliance directly benefits the users of space. An example is indicator VS1.1, within the security dimension of the housing block: “All areas of the entrance to the housing block are visible from the access point”.

Type b indicators have associated sub-indicators that are mutually exclusive—that is, one or the other may occur to meet the gender perspective, but both cannot exist simultaneously in the given space. In this case, one of the level 2 sub-indicators is counted to evaluate the level 1 indicator. For example, VS1.5 is the level 1 indicator: “The staircase is illuminated by motion sensors”, and it has two mutually exclusive sub-indicators: VS1.5.1, “The entire staircase is illuminated by a single sensor activation”, and VS1.5.2, “The staircase is illuminated in sections, floor by floor, by motion sensors”.

In this situation, both options are positive from a gender perspective, but they cannot occur simultaneously, so only one is counted. Although the specific method of illumination may seem irrelevant at first, it is deemed important because it relates to the energy efficiency dimension, which should be considered when planning potential interventions.

A third type of indicator, classified as Type c, has several associated level 2 sub-indicators that must all be positively evaluated for the main indicator to be assessed as compliant. An example of this is VCU.2, “Common areas facilitate neighbourly interactions and gatherings”. To determine compliance, one must assess whether each of the common areas supports this type of interaction, meaning that all three level 2 sub-indicators must be positively evaluated: VCU2.1, “Entrance areas”; VCU2.2, “Corridors”; and VCU2.3, “Landings”.

Type d indicators are similar to Type c indicators, except that instead of counting only the main indicator, we count all the level 2 sub-indicators due to their importance and relevance for achieving a gender perspective. An example of this is BD.M.2, “The neighbourhood is adequately served by public transport”. Compliance with this main indicator is determined by its sub-indicators: “There is a metro station within 300 metres”; “There are bus stops within 300 metres”; and “There is a train station within a 300-m radius”. Since all these options are important, the three sub-indicators are counted, but the level 1 indicator is not.

Type e indicators have associated sub-indicators, and both levels are counted separately, with the condition that the level 2 sub-indicator must be fulfilled for the level 1 indicator to be considered. This occurs, for example, with GA.A.1 “Accessible public spaces exist”, which includes two sub-indicators: “For people with mobility difficulties” and “For people with sensory, functional, or invisible disabilities”. If the spaces exist, the main indicator is considered fulfilled. If not, the indicator cannot be evaluated.

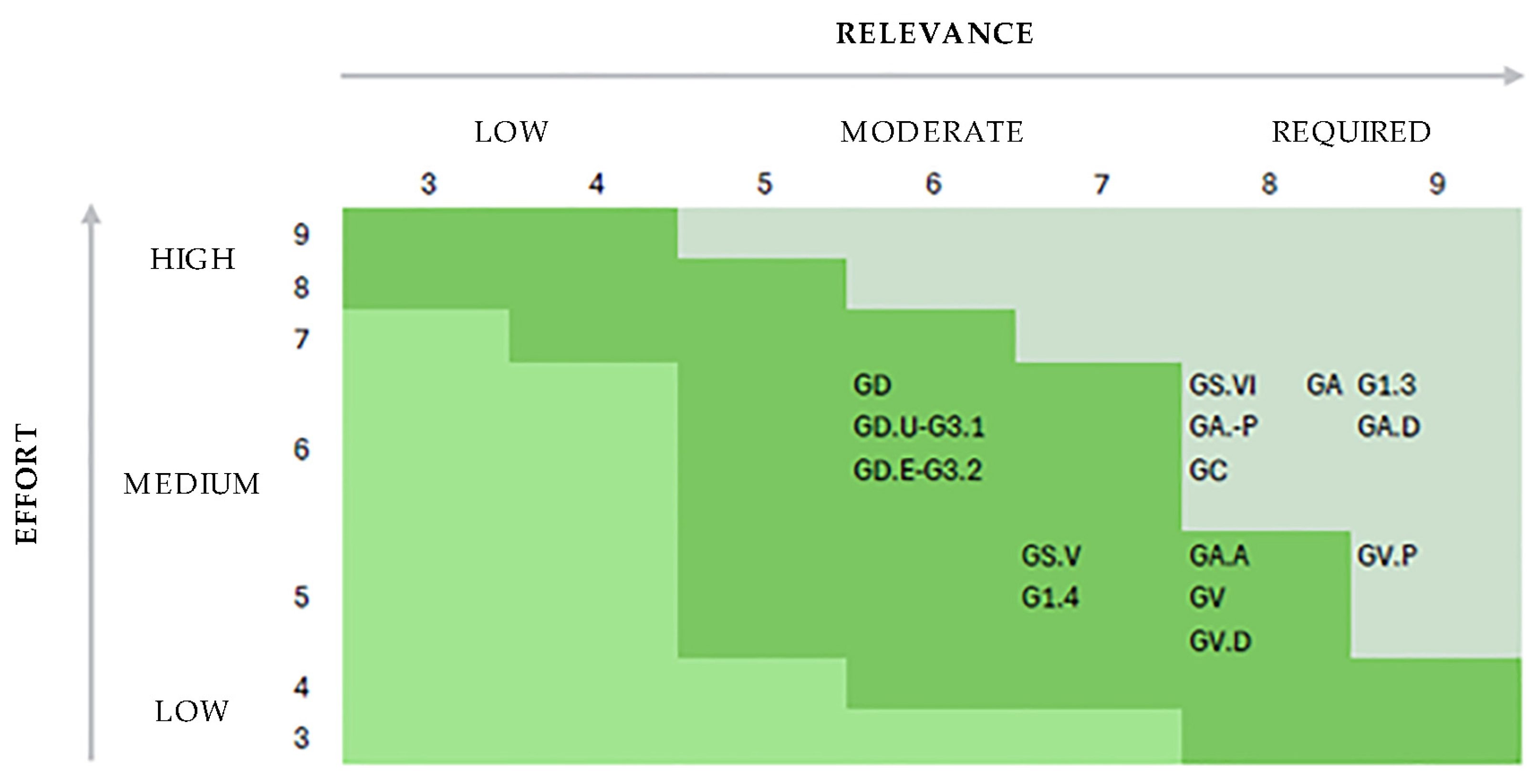

Once the indicators have been evaluated, the indicators aligned with the gender perspective are counted. Next, the non-compliant indicators are selected and categorised by their importance for achieving inclusive spaces, and they are grouped by common solutions. For each group of indicators with similar solutions, the effort required to implement the intervention is assessed, and the results are presented in a relationship matrix for each scale. On the

x-axis, the solutions that contribute most to the gender perspective are arranged in increasing order. On the

y-axis, the economic effort required for implementation is represented (

Figure 9). This matrix layout allows the institutions responsible for decision-making to prioritise their interventions.

The assessment carried out in the case study of the three neighbourhoods in Fuenlabrada provided some highly relevant indications in regard to the areas for action. At the housing level, a distinction should be made between entrance areas, where actions related to visibility and care of common spaces stand out, and dwellings, where the critical indicators were those related to the laundry cycle, storage and spatial flexibility, which is extremely limited, especially in kitchens and bathrooms.

The inter-block level analysis identified that the key actions for improving spaces from a gender perspective are those that require a medium-low effort and primarily relate to the vitality and diversity of space use.

The neighbourhood-scale analysis revealed that the key areas for intervention are mobility and connectivity. Priority should be given to better traffic regulation, more investment in public transport and soft mobility focused on pedestrians. These actions must be complemented by creating a safer environment through improvements in accessible design, pavement maintenance and lighting.

4. Discussion

The development and implementation of the tool across three neighbourhoods in the municipality of Fuenlabrada demonstrate that it is a consistent and user-friendly instrument. Its strengths include its comprehensive, multi-scale approach, the rigour with which the indicators are constructed, the inclusion of participatory information-gathering activities with citizens, the use of graphic resources, and the depth of its gender perspective.

This tool provides a holistic understanding of the places analysed, identifying spatial aspects at multiple scales that can affect and complement one another. The bibliographic sources used to construct the indicators ensure their academic rigour. Similarly, the triangulation of the collected data ensures the quality and representativeness of the information used to assess it. In this regard, the use of participatory techniques that allow citizens and municipal employees who work in the places studied to share their vision of the spaces they inhabit are particularly valuable. Additionally, the graphic tools designed during the research, such as analysis sheets, diagrams for participation dynamics, and symbols used for representation on plans, facilitate the interpretation of the information collected through direct observation. These attributes, when coupled with an understanding of the gender perspective as a paradigm based on the belief that anything that benefits women will benefit us all, give the tool the potential to be used in any neighbourhood with similar characteristics.

The tool’s limitations include the amount of time required to evaluate the spaces, possible difficulties in accessing all the necessary initial graphic documentation, and potential subjectivity in the assessment of some indicators related to safety, representativeness, and vitality.

The application of the method requires the availability of planimetries and previous urban studies of the neighbourhoods to be analysed. The acquisition of this documentation, depending on the municipality, may be costly and will depend on the goodwill of staff in the municipal planning office. This stage may therefore be subject to an increase in the already extensive amount of time required for research. Beyond the initial phase of analysing graphic documentation, the method requires the use of various techniques to collect information and develop graphic resources on three different scales. As a result, this stage relies heavily on having access to a solid team of experts who can complete the work within a reasonable timeframe.

On another note, it is important to recognise the potential for subjectivity in the assessment of indicators related to safety, representativeness and vitality. Every neighbourhood has a unique social context and identity, and these specific characteristics must be taken into account and respected to avoid subjective judgements and ensure that the information collected through instruments that include citizens can be relied upon. Consequently, before applying the tool in a new urban context, an analysis of its history and urban and building development must be carried out, making any additional adjustments beyond the initial testing phase where necessary.

5. Final Reflections

The methodological tool developed in this project allows for a rigorous and situated evaluation of urban, intermediate, and domestic spaces from a gender perspective. Its inter-scale design—evaluating at the neighbourhood, inter-block, and housing levels—and its multidimensional approach—incorporating qualitative and quantitative indicators grouped into dimensions such as safety, accessibility, diversity, vitality, and representativeness—offer a critical reading of the built environment based on the everyday experiences of its inhabitants.

As stated in the hypothesis of this work: urban spaces have historically been designed from an androcentric perspective that excludes diverse bodies, identities, and ways of life. The application of the tool in the neighbourhoods of Fuenlabrada evidence but does not prove how this exclusion manifests across multiple scales, while also revealing that deficiencies at one scale can be offset by strengths at another, highlighting the importance of an integrated analysis.

The research builds on previous studies that emphasise the need to mainstream the gender perspective in urban planning and theoretical frameworks such as feminist urbanism and ecofeminism, which reclaim everyday life as a situated political experience. In this sense, the tool enables the identification of spatial deficits while also highlighting dissident urban practices and promoting spatial justice.

Moreover, the methodology employed—combining direct observation, graphic analysis, interviews, and focus groups—ensures active citizen participation in the evaluation of the environment, reinforcing the collective and transformative nature of architecture and urbanism with a gender perspective. The inclusion of children, older adults and vulnerable groups in the data collection process provides an intergenerational and plural perspective that enriches both diagnosis and decision-making.

Unlike the literature studied, which does not provide interrelated multi-scale indicators, this publication contributes to advancing scientific knowledge by developing a methodological tool for evaluating urban, intermediate, and domestic spaces from a gender perspective, articulated across three scales of approach—neighbourhood, inter-block, and housing—and organised into transversal dimensions such as safety, accessibility, diversity, vitality, and representativeness. Its originality lies in combining multi-scalar and multidimensional approaches, integrating qualitative and quantitative indicators that encompass everyday life (work, care, and domestic activities) and incorporating parameters not previously considered, such as informal surveillance, public space maintenance, mixed uses, and spatial flexibility. As a result, this proposal goes beyond theoretical frameworks to offer an operational, replicable, and scalable instrument that can be applied in real-world contexts.

Furthermore, the tool is based on a systematic six-stage process—from literature review to pilot testing—and on the definition of a comprehensive framework composed of six transversal dimensions and eight complementary ones, enabling the simultaneous evaluation of urban and residential quality. Its design incorporates mechanisms for citizen participation, including vulnerable and intergenerational groups, and establishes clear criteria for prioritising interventions through matrices that cross relevance and implementation effort. In doing so, the study not only diagnoses spatial inequalities rooted in historically androcentric urbanism but also provides a solid foundation for guiding public policies toward inclusive and equitable environments. The work advances the integration of gender as a structuring principle of space, rather than merely an analytical category, and demonstrates how applying this tool enables the diagnosis of spatial inequalities historically linked to androcentric design. Furthermore, it incorporates participatory mechanisms involving vulnerable and intergenerational groups, reinforcing the collective and situated dimension of urban analysis.

Finally, the tool is presented as replicable, flexible, and scalable, making it a solid foundation for future research and for the formulation of public policies aimed at urban equity. By combining theory, verifiable indicators, and criteria for prioritizing interventions, this research establishes a solid foundation for future applications in gender-sensitive urban planning. Its registration for intellectual property protection and open-access publication will ensure its accessibility and potential impact in other geographical and temporal contexts.