Study on the Evaluation and Driving Factors of Interprovincial Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer Under China’s Food Security Objective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

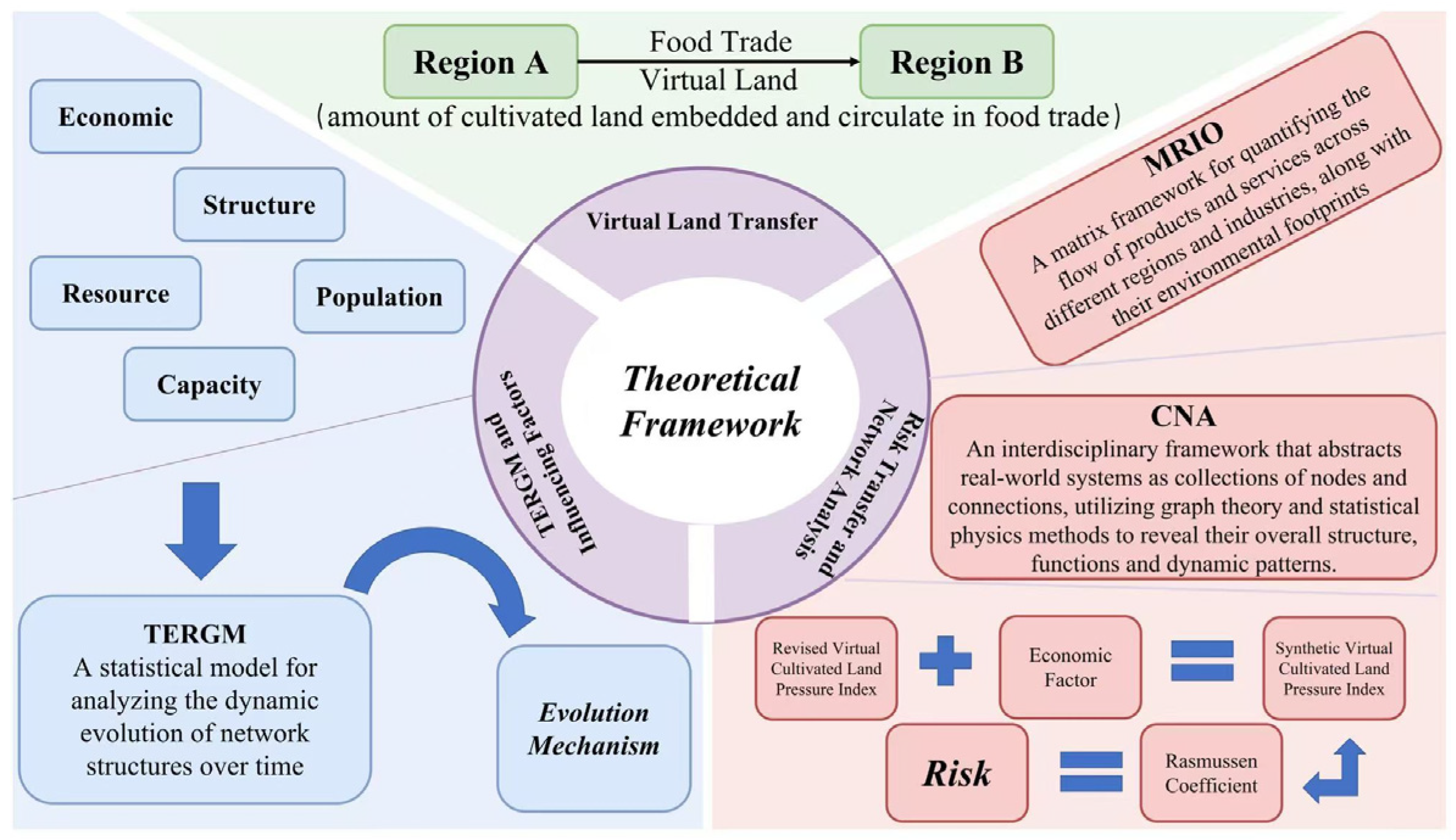

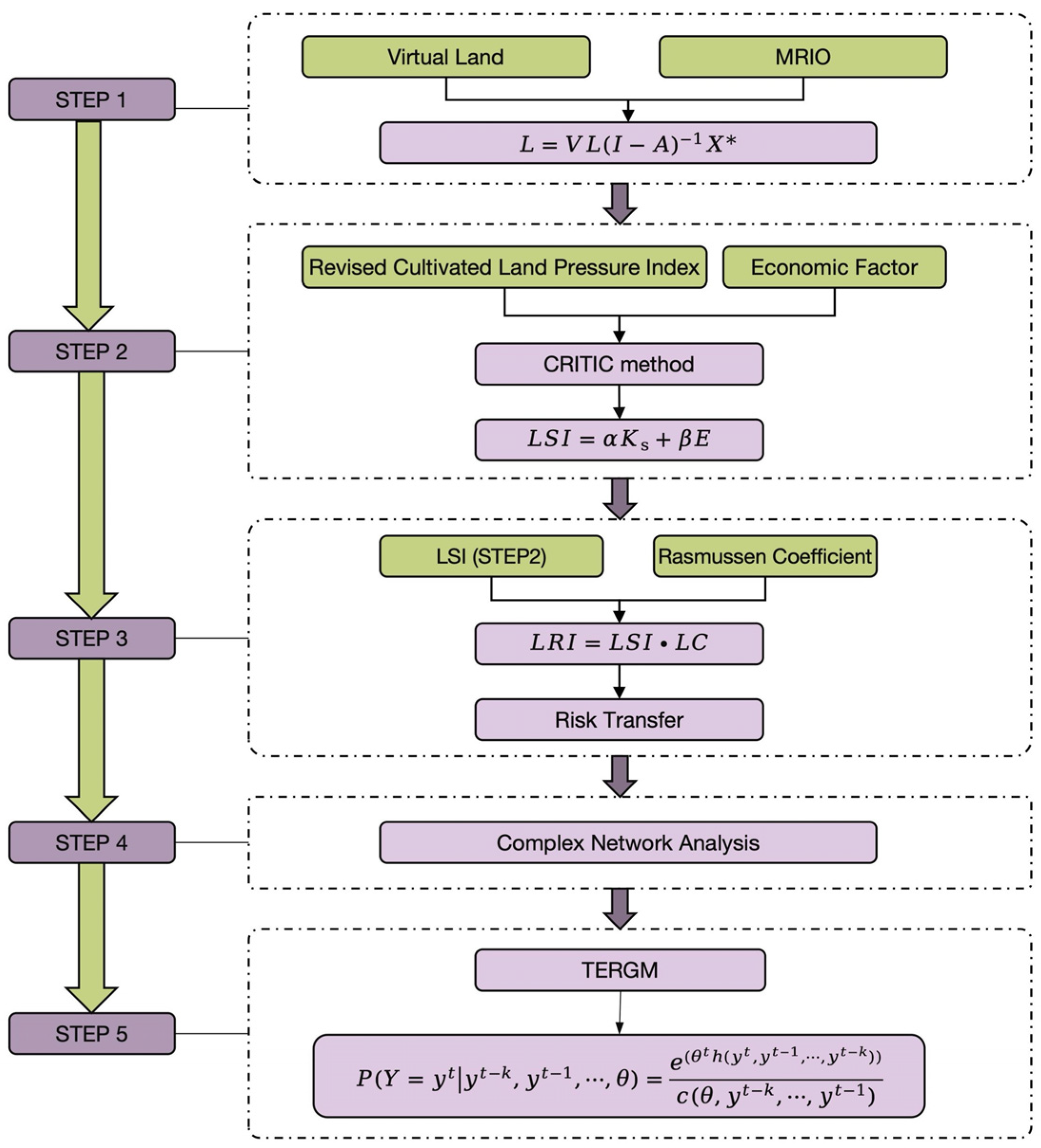

3. Methods

3.1. Multi-Regional Input–Output Model

3.2. Synthetic Cultivated Land Pressure Index

3.2.1. Revised Cultivated Land Pressure Index

3.2.2. CRITIC Method

3.3. Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Assessment Model

3.3.1. Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Index

3.3.2. Rasmussen Coefficient

3.3.3. The Transfer of Cultivated Land Risk

3.4. Network Connectivity Feature Analysis

3.5. Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model

3.6. Variables Selection and Data Sources

4. Results

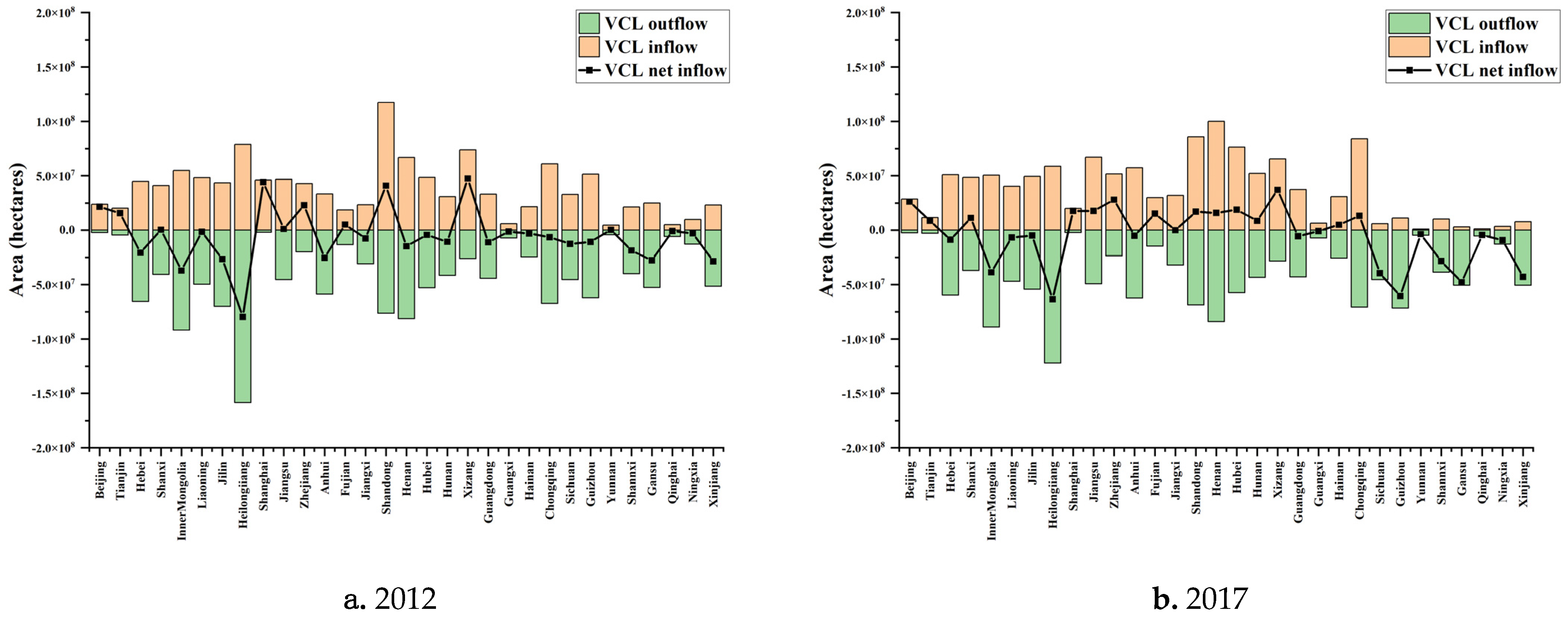

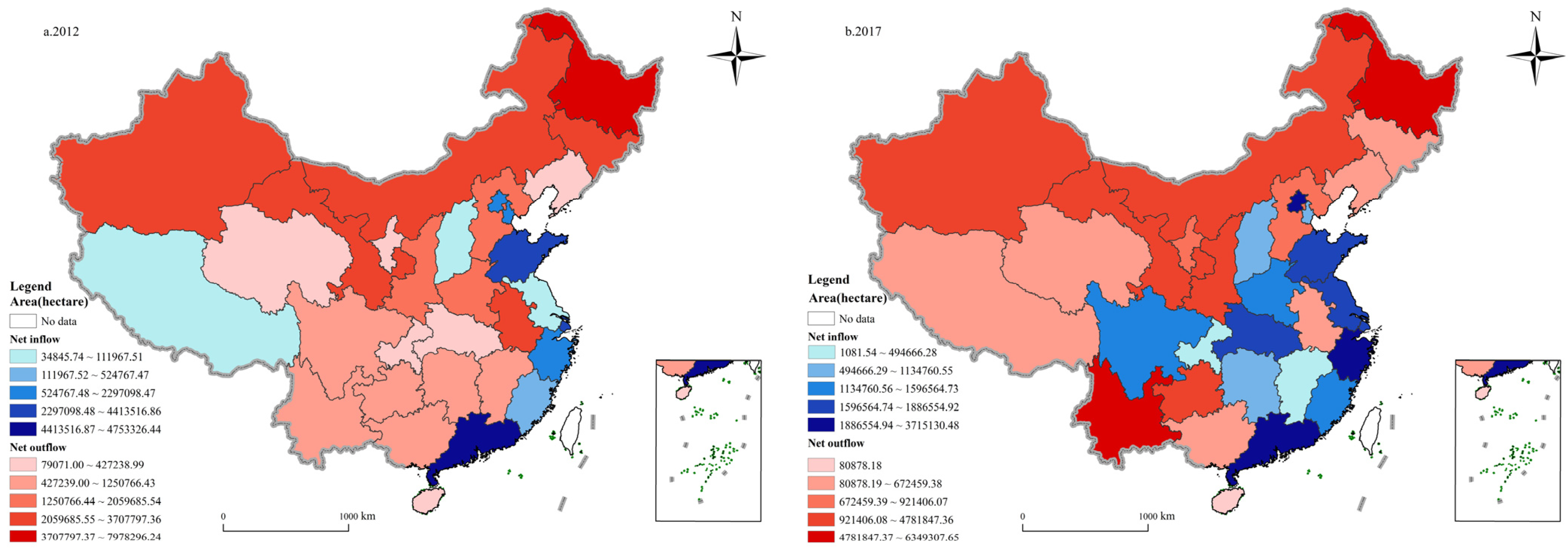

4.1. Analysis of Inter-Regional Virtual Cultivated Land Trade

4.1.1. Virtual Cultivated Land Trade Overview and Spatial Pattern

4.1.2. Motif Analysis

4.2. Analysis of Inter-Regional Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer

4.3. Network Analysis of Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer

4.3.1. Overall Structural Characteristics of the Network

4.3.2. Individual Node Characteristics Analysis

4.3.3. Block Model Analysis

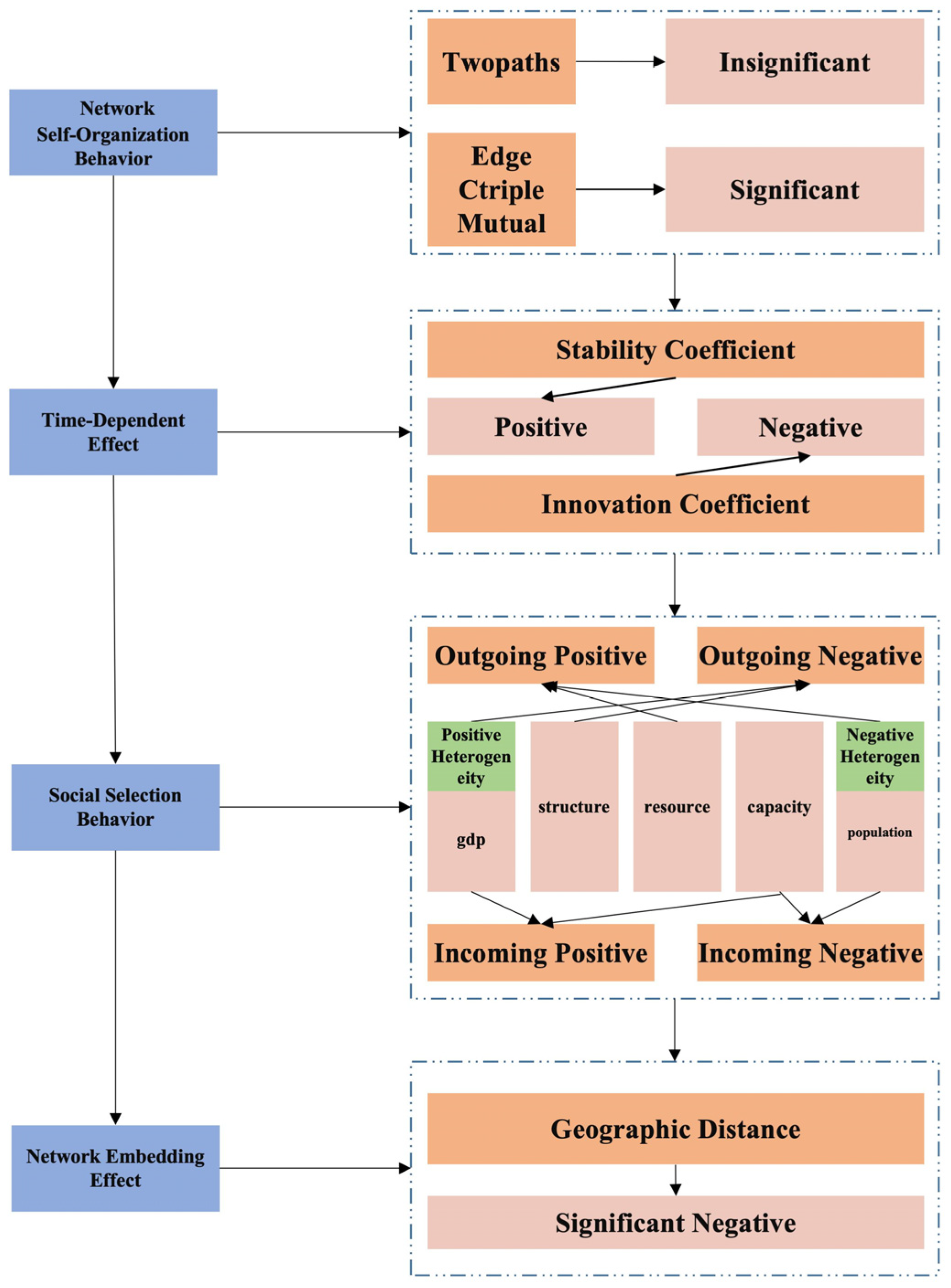

4.4. Identification of Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer Network Formation Mechanisms

4.4.1. Network Self-Organization Behavior

4.4.2. Time-Dependent Effects

4.4.3. Social Selection Behavior

4.4.4. Network Embedding Effect

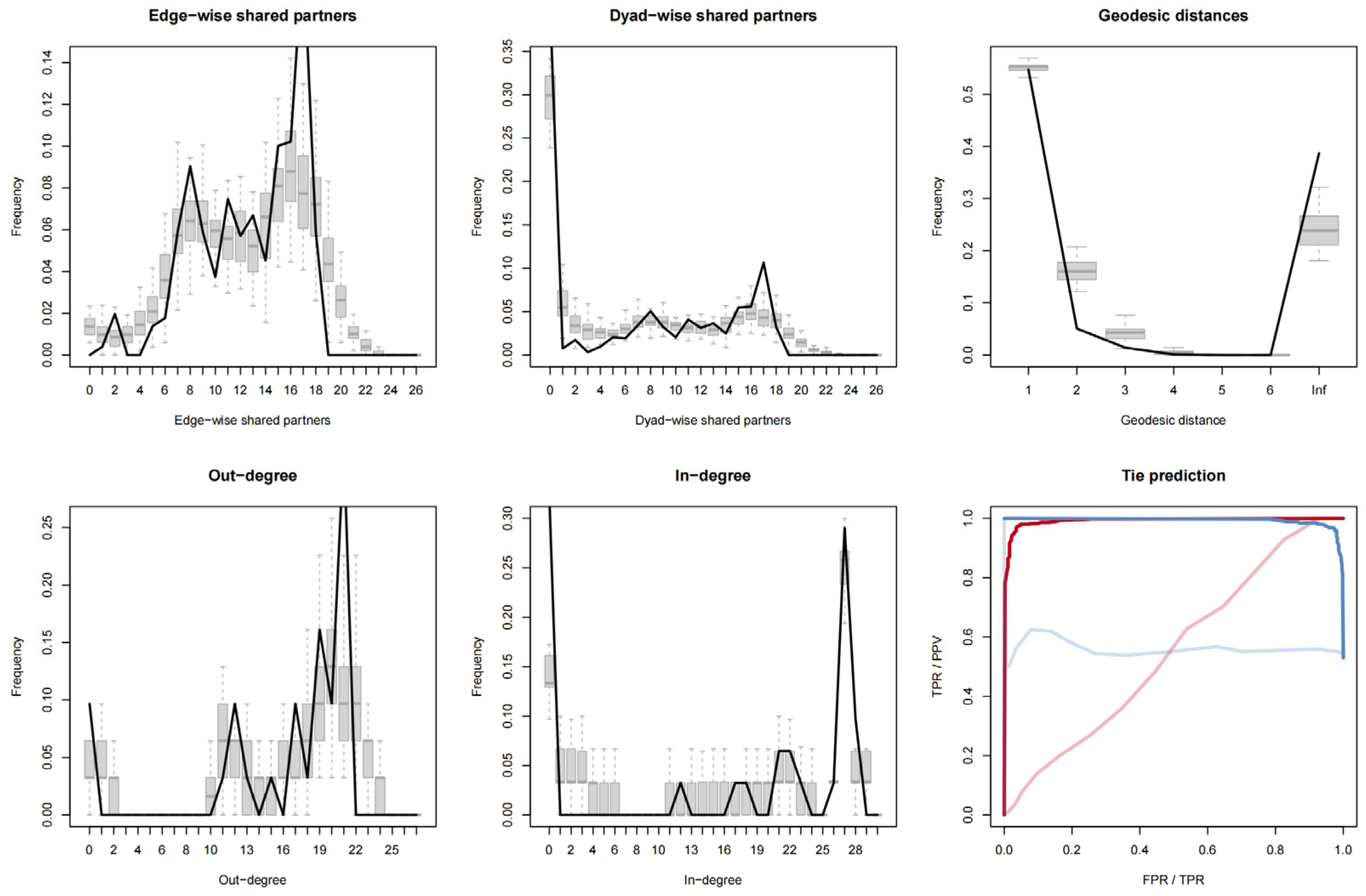

4.5. Model Validation

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

- In terms of virtual cultivated land trade, China’s total amount in 2017 was slightly lower than in 2012. The number of China’s net virtual cultivated land inflow provinces increased significantly, which reflects the shrinking of major grain-producing regions and the deepening imbalance of supply and demand. On a micro-level, characteristics of connectivity, agglomeration and reciprocity were recognized within the network. Although key motifs were found to be different, no significant variations were detected in the transfer patterns from 2012 to 2017, and inter-provincial virtual cultivated land trade tended to be more simplified but less innovative.

- Although the overall pattern of the risk value matrix has only minor changes, it is evident that the value of more inter-provincial trade has decreased. The pattern of inter-provincial risk transfer occurs from the majority of less developed provinces to the minority of economically developed provinces, which further underscores the inequality of the responsibility of food security. While the virtual cultivated land risk transfer network maintained a strongly connected structure, notable changes were identified in its spatial organization. The rise in in-degree centralization and average distance, along with the decline in out-degree centralization, indicate that pressures and risks have become more evenly shared; a smaller group of developed provinces continue to absorb disproportionate levels of risk value, intensifying spatial inequality. Block model analysis divided 31 provinces into a net recipient block, net sender block, broker block and major net recipient block. From 2012 to 2017, the proportion of net recipient blocks increased significantly, indicating a worrying trend. The members of different blocks varied during the studied period, but overall, major grain-production regions bear more risks and economically developed provinces are the net recipients.

- It was found that a small number of economically developed provinces are in a favorable position while less developed provinces bear more cultivated land pressures and risks, with their evolution tending towards deterioration. As for spatial-temporal dimension, the virtual cultivated land risk transfer network exhibits significant time-dependent effects, manifesting itself in strong path-dependent characteristics and limited path-innovation capabilities. In terms of influencing factors, the impact of economic development is similar to that of industrial structure. Resource endowment solely showed a positive outgoing effect while grain production capacity was only significant in incoming effects. Contrary to common belief, population was actually beneficial for the generation of sending relationships and negatively associated with the generation of receiving effects.

5.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 2012 | 2017 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out-Deg | In-Deg | Out-Clos | In-Close | Between | Out-Deg | In-Deg | Out-Clos | In-Close | Between | |

| Beijing | 0 | 28 | 120 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 150 | 38 | 0 |

| Tianjin | 0 | 27 | 120 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 150 | 38 | 0 |

| Hebei | 21 | 0 | 57 | 120 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Shanxi | 19 | 25 | 61 | 43 | 6.723 | 20 | 18 | 70 | 52 | 10.248 |

| Inner mongolia | 19 | 23 | 61 | 45 | 3.507 | 20 | 12 | 70 | 67 | 0 |

| Liaoning | 17 | 26 | 63 | 42 | 3.943 | 19 | 22 | 71 | 47 | 4.099 |

| Jilin | 21 | 1 | 57 | 117 | 0 | 20 | 17 | 70 | 56 | 5.039 |

| Heilongiiang | 24 | 0 | 48 | 120 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Shanghai | 0 | 28 | 120 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 150 | 38 | 0 |

| Jiangsu | 17 | 26 | 63 | 42 | 3.943 | 17 | 27 | 74 | 42 | 7.035 |

| Zhejiang | 14 | 26 | 67 | 42 | 0.602 | 12 | 27 | 80 | 42 | 0.184 |

| Anhui | 23 | 0 | 51 | 120 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Fujian | 15 | 26 | 66 | 42 | 1.124 | 11 | 27 | 83 | 42 | 0 |

| Jiangxi | 21 | 5 | 57 | 105 | 0 | 19 | 21 | 71 | 48 | 2.692 |

| Shandong | 20 | 22 | 60 | 46 | 8.325 | 19 | 23 | 71 | 46 | 7.253 |

| Henan | 23 | 0 | 51 | 120 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Hubei | 20 | 20 | 60 | 48 | 4.333 | 19 | 22 | 71 | 47 | 4.099 |

| Hunan | 21 | 0 | 57 | 120 | 0 | 19 | 21 | 71 | 48 | 2.692 |

| Tibet | 16 | 26 | 64 | 42 | 2.187 | 17 | 27 | 74 | 42 | 7.035 |

| Guangdong | 20 | 14 | 60 | 58 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Guangxi | 14 | 26 | 67 | 42 | 0.602 | 12 | 27 | 80 | 42 | 0.184 |

| Hainan | 18 | 25 | 62 | 43 | 3.878 | 17 | 27 | 74 | 42 | 7.035 |

| Chongqing | 23 | 0 | 51 | 120 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Sichuan | 20 | 18 | 60 | 51 | 1.793 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Guizhou | 23 | 0 | 51 | 120 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Yunnan | 11 | 26 | 72 | 42 | 0 | 13 | 27 | 78 | 42 | 1.137 |

| Shaanxi | 19 | 25 | 61 | 43 | 6.723 | 18 | 26 | 72 | 43 | 13.408 |

| Gansu | 20 | 17 | 60 | 52 | 1.128 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| Qinghai | 2 | 27 | 114 | 39 | 0 | 12 | 27 | 80 | 42 | 0.184 |

| Ningxia | 16 | 26 | 64 | 42 | 2.187 | 15 | 27 | 76 | 42 | 3.677 |

| Xinjiang | 21 | 5 | 57 | 105 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 66 | 150 | 0 |

| 2012 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.27918552 | 0.565746373 |

| Tianjin | 1.093607306 | 1.006181319 |

| Hebei | 1.340528164 | 1.285738391 |

| Shanxi | 0.937493845 | 0.881986046 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.777693228 | 0.972321698 |

| Liaoning | 0.843807615 | 0.839226808 |

| Jilin | 0.758649729 | 0.871112256 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.771369138 | 0.931962614 |

| Shanghai | 2.063297872 | 1.486951983 |

| Jiangsu | 1.669925797 | 1.652286095 |

| Zhejiang | 1.174431531 | 1.002073849 |

| Anhui | 1.524664287 | 1.487471876 |

| Fujian | 1.690141897 | 1.158875009 |

| Jiangxi | 1.789731131 | 1.827122489 |

| Shandong | 1.423500131 | 1.463516825 |

| Henan | 1.751897801 | 1.816069425 |

| Hubei | 1.529515335 | 1.519528639 |

| Hunan | 2.051060241 | 2.004818116 |

| Tibet | 1.765675057 | 1.626149171 |

| Guangdong | 1.376465264 | 1.360660969 |

| Guangxi | 1.175515818 | 0.98200443 |

| Hainan | 1.416001629 | 1.409232847 |

| Chongqing | 1.433853007 | 1.423764349 |

| Sichuan | 1.139599824 | 1.252412145 |

| Guizhou | 1.112604502 | 1.092945778 |

| Yunnan | 0.552036199 | 0.572297297 |

| Shaanxi | 1.061698397 | 1.02033694 |

| Gansu | 0.76218628 | 0.69778687 |

| Qinghai | 0.942517007 | 0.941026945 |

| Ningxia | 0.968930523 | 0.878052562 |

| Xinjiang | 0.993003876 | 1.12355905 |

| 2012 | Inflow | 2012 | Outflow | 2017 | Inflow | 2017 | Outflow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shandong | 117,238,143.2 | Heilongjiang | 158,640,796.4 | Henan | 100,090,605.5 | Heilongjiang | 122,152,830.7 |

| Heilongjiang | 78,857,834 | Inner Mongolia | 91,988,687.44 | Shandong | 85,814,332.18 | Inner Mongolia | 89,160,686.13 |

| Guangdong | 73,751,616.67 | Henan | 81,410,856.9 | Sichuan | 83,931,067.77 | Henan | 84,124,958.2 |

| Henan | 66,727,843.23 | Shandong | 76,341,551.61 | Hubei | 76,254,832.53 | Yunnan | 71,692,530.99 |

| Sichuan | 60,932,183.13 | Jilin | 70,065,887.13 | Jiangsu | 67,006,302.33 | Sichuan | 70,696,948.01 |

| Variables | Unit |

|---|---|

| Q | ¥ |

| L | Hectare |

| VL | Hectare/¥ |

| VCL | Hectare |

| Structure | GDP | Resource | Population | Capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.504171685 | 27,327.1 | 4351.009677 | 4478.516129 | 476.383871 |

| Median | 0.4923636 | 20,006.31 | 4387.5 | 3835 | 421.3 |

| Max | 0.42351525 | 1310.92 | 191.6 | 337 | 18.9 |

| Min | 0.805561604 | 89,705.23 | 15,845.7 | 11,169 | 1953.2 |

| Source | China Statistical Yearbook | China Statistical Yearbook | China Rural Statistical Yearbook | China Statistical Yearbook | China Rural Statistical Yearbook |

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| edges | total number of edges in network |

| mutual | number of interconnected pairs |

| twopath | number of indirect connections of length 2 |

| Ctriple | number of directed cyclic triples |

| stability | number of edges that remain unchanged from the previous time point to the current time point |

| innovation | number of newly emerged edges from the previous time point to the current time point |

| absdiff | the impact of the magnitude of the difference between two nodes in a certain numerical attribute on the possibility of forming a connection between them |

References

- Xie, Z.; Lin, X.; Jiang, C.; Dang, Y.; Kong, X.; Lin, C. Establishment of an inter-provincial compensation system for farmland protection in China: A framework from zoning-integrative transferable development rights. Land Use Policy 2025, 150, 107456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Mertes, C.M. Expansion and growth in Chinese cities, 1978–2010. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Ma, Z. Understanding the distribution patterns and underlying mechanisms of non-grain use of cultivated land in rural China. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 106, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmelin, N.B. National specialization policy versus farmers’ priorities: Balancing subsistence farming and cash cropping in Nepal. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 83, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.; Wollni, M.; Qaim, M. Oil palm boom and land-use dynamics in Indonesia: The role of policies and socioeconomic factors. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.; Xing, Z.; Chen, W.; Shi, Y.; Shi, L.; Feng, X.; Ma, Y. Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Zonal Control of Non-Grain Cultivated Land in Major Grain Producing Areas: A Case Study of Henan Province. Land 2025, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fu, M. Degree of non-grain production of cultivated land and its impact on grain production in China: Analysis of 2481 county-level units. Land Use Policy 2025, 155, 107586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahui, W.; Aoxi, Y.; Qingyuan, Y. The extent, drivers and production loss of farmland abandonment in China: Evidence from a spatiotemporal analysis of farm households survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, X.; Xin, L.; Wang, X. Improving mechanization conditions or encouraging non-grain crop production? Strategies for mitigating farmland abandonment in China’s mountainous areas. Land Use Policy 2025, 149, 107421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X. Driving factors of farmers’ non-grain production of cropland in the hilly and mountainous areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Cultivated land protection and rational use in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibatullin, S.; Dorosh, Y.; Sakal, O.; Krupin, V.; Kharytonenko, R.; Bratinova, M. Agricultural Land Market in Ukraine: Challenges of Trade Liberalization and Future Land Policy Reforms. Land 2024, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Qian, K.; Lin, L.; Wang, K.; Guan, T.; Gan, M. Identifying the driving forces of non-grain production expansion in rural China and its implications for policies on cultivated land protection. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, C.; Yao, R. Cropland compensation in mountainous areas in China aggravates non-grain production: Evidence from Fujian Province. Land Use Policy 2024, 138, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Ji, H. Virtual Land and Water Flows and Driving Factors Related to Livestock Products Trade in China. Land 2023, 12, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichelns, D. The role of ‘virtual water’ in efforts to achieve food security and other national goals, with an example from Egypt. Agric. Water Manag. 2001, 49, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, K.; Hubacek, K. Tele-connecting local consumption to global land use. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Hao, S.; Yao, M.; Chen, W.; Zhang, P. Unbalanced economic benefits and the electricity-related carbon emissions embodied in China’s interprovincial trade. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 263, 110390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; Liao, J. Embodied Carbon in China’s Export Trade: A Multi Region Input-Output Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhi, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Song, M. Unveiling the unequal variation of regional carbon risk under inter-provincial trade in China. Environ. Impact Assesment Rev. 2024, 105, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.A. Fortunately There Are Substitutes for Water: Otherwise Our Hydropolitical Futures Would be Impossible; Overseas Development Administration: London, UK, 1993.

- Luo, Z.; Long, A.; Huang, H.; Xu, Z. Virtual Land Strategy and Socialization of Management of Sustainable Utilization of Land Resources. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2004, 26, 624–631. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Chen, G. Global arable land transfers embodied in China’s mainland’s foreign trade. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuertenberger, L.; Koellner, T.; Binder, C.R. Virtual land use and agricultural trade: Estimating environmental and socio-economic impacts. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 57, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, W.; Niu, S.; Liu, A.; Kastner, T.; Bie, Q.; Wang, X.; Cheng, S. Trends in global virtual land trade in relation to agricultural products. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ben, P.; Chen, D.; Chen, J.; Tong, G.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, B. Virtual land, water, and carbon flow in the inter-province trade of staple crops in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Song, M. Interprovincial industrial virtual scarce water flow and water scarcity risk in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Bai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhang, S.; Shu, J. Virtual arable land trade reveals inequalities in the North China Plain: Regional heterogeneity and influential determinants. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 138, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kang, J.N.; Han, M.S. Global environmental inequality: Evidence from embodied land and virtual water trade. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Bruckner, M.; Geng, Y.; Bleischwitz, R. Trends and driving forces of China’s virtual land consumption and trade. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, G.Q.P.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Virtual built-up land transfers embodied in China’s interregional trade. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, H. Carbon footprint and embodied carbon transfer at city level: A nested MRIO analysis of Central Plain urban agglomeration in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Marchamalo, M.; Alvarez, S. Organization environmental footprint applying a multi-regional input-output analysis: A case study of a wood parquet company in Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 618, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontief, W. Environmental Repercussions and the Economic Structure: An Input-Output Approach. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1970, 52, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Liang, W.; Fu, B.; Li, J.; Yan, J. Uncovering the structure and evolution of global virtual water and agricultural land network. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 51, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, H.; Xing, Z.; Chu, B.; Wang, H. Virtual land trade and associated risks to food security in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; Sun, D. Uncovering the patterns and driving forces of virtual forestland flows in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Sang, M.; Teng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L. Land and water resource effects of power structure transformation in China: Telecoupling and spatial redistribution. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun-Long, C.; Ze-Qiang, F.U.; Er-Fu, D. The Minimum Area Per Capita of Cultivated Land and Its Implication for the Optimization of Land Resource Allocation. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2002, 57, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, M.; Wen, L.; Zhang, A. Does urbanization inevitably exacerbate cropland pressure? The multiscale evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 504, 145413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; Song, G.; Liu, Y. Optimization of cultivated land pattern for achieving cultivated land system security: A case study in Heilongjiang Province, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Who will feed China: The role and explanation of China’s farmland pressure in food security. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 2216–2226. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Z. Does urbanization increase the pressure of cultivated land? Evid. Based Interprov. Panel Data China 2020, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Taherzadeh, O.; Bithell, M.; Richards, K. Water, energy and land insecurity in global supply chains. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 2021, 67, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qu, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.; Xu, M. Virtual water scarcity risk in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Qi, J.; Zhi, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q.; Na, X. Study on the pattern and driving factors of water scarcity risk transfer networks in China from the perspective of transfer value—Based on complex network methods. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ling, R.; Yang, M.; Miao, R.; Zhou, H.; Xiang, H.; Jing, Y.; Ma, R.; Xu, G. A comprehensive risk management framework for NIMBY projects: Integrating social network analysis and risk transmission chains. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.-R.; Sun, F.-Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; Liu, H.-L. Ecological Comprehensive Efficiency and Driving Mechanisms of China’s Water–Energy–Food System and Climate Change System Based on the Carbon Nexus: Insights from the Integration of Network DEA and the Geographic Detector. Land 2025, 14, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Ma, Y.; Li, X. Regional water footprint evaluation and trend analysis of China—Based on interregional input–output model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 112, 4674–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Hou, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H. Temporal dynamics, driving factor and mutual relationship analysis for the holistic virtual water trade network in China (2002–2017). Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Han, Q.; Yang, D.; de Vries, B. Historical changes and driving factors of food-water-energy footprint consumption: A Case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei city agglomeration. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 122, 106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo, R.; Fang, D.; Ye, S.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil erosion drivers in Chinese croplands. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 485, 144405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanneke, S.; Fu, W.; Xing, E.P. Discrete temporal models of social networks. Electron. J. Stat. 2010, 4, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, M. Structural dynamics of embodied carbon in global manufacturing trade: A network-based microlevel analysis. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 62, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, P.; Ting, X.; Ling, D. The structural change and influencing factors of carbon transfer network in global value chains. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 318, 115558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, C.; Xu, M.; Sun, S. China’s Land Uses in the Multi-Region Input–Output Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Revealing the process and mechanism of non-grain production of cropland in rapidly urbanized Deqing County of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 123948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, C.; Chen, J.; Yi, B.; Li, H. Examining the reliable trend of global urban land use efficiency from 1985 to 2020 using robust indicators and analysis tools. Habitat Int. 2025, 163, 103477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.; Langarita, R.; Sánchez-Chóliz, J. The electricity industry in Spain: A structural analysis using a disaggregated input-output model. Energy 2017, 141, 2640–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiuli, L. A Method to Visualize the Skeleton Industrial Structure with Input-Output Analysis and Its Application in China, Japan and USA. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2018, 31, 1554–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Guitton, H.; Rasmussen, P.N. Studies in Inter-Sectoral Relations. Economica 1957, 8, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robati, M.; Oldfield, P.; Nezhad, A.A.; Carmichael, D.G.; Kuru, A. Carbon value engineering: A framework for integrating embodied carbon and cost reduction strategies in building design. Build. Environ. 2021, 192, 107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, W.; Song, M.; Guan, D. Regional determinants of China’s consumption-based emissions in the economic transition. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 074001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.C.; Boorman, S.A.; Breiger, R.L. Social Structure from Multiple Networks. I. Blockmodels of Roles and Positions. Am. J. Sociol. 1976, 81, 730–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, J.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Shi, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Multi-scale near-long-range flow measurement and analysis of virtual water in China based on multi-regional input-output model and machine learning. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 175, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, Q.; Qi, X.; Sun, R.; Wang, M. Unpacking China’s land use and trade-driven land transfers through telecoupling. Land Use Policy 2025, 158, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Deng, X.; Weng, C.; Shu, J.; Wang, C. Tele-connecting local consumption to cultivated land use and hidden drivers in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Zheng, P.; Tan, K.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. Value compensation of net carbon sequestration alleviates the trend of abandoned farmland: A quantification of paddy field system in China based on perspectives of grain security and carbon neutrality. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Jankowski, P.; Blaschke, T. A GIS based spatially-explicit sensitivity and uncertainty analysis approach for multi-criteria decision analysis. Comput. Geosci. 2014, 64, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Indicator Variability | Indicator Conflict | Amount of Information | Weight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| modified cultivated land pressure index 2012 | 0.235 | 0.502 | 0.118 | 46.673 |

| level of economic development 2012 | 0.269 | 0.502 | 0.135 | 53.327 |

| modified cultivated land pressure index 2017 | 0.177 | 0.467 | 0.083 | 39.215 |

| level of economic development 2017 | 0.274 | 0.467 | 0.128 | 60.785 |

| Indicators | LPI 2012 | LPI 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.958638056 | 1 |

| Tianjin | 0.829907636 | 0.575840735 |

| Hebei | 0.158546132 | 0.106460503 |

| Shanxi | 0.230739536 | 0.098342087 |

| Inner mongolia | 0.347456678 | 0.215035207 |

| Liaoning | 0.317608912 | 0.157430259 |

| Jilin | 0.172075267 | 0.159321938 |

| Heilongiiang | 0.120865655 | 0.081283325 |

| Shanghai | 0.742628651 | 0.647498392 |

| Jiangsu | 0.368051095 | 0.47848008 |

| Zhejiang | 0.488567252 | 0.424476507 |

| Anhui | 0.08459185 | 0.092496032 |

| Fujian | 0.335084107 | 0.355914254 |

| Jiangxi | 0.078987055 | 0.092726108 |

| Shandong | 0.251449029 | 0.270606258 |

| Henan | 0.089496731 | 0.11084687 |

| Hubei | 0.160614742 | 0.195194236 |

| Hunan | 0.10534227 | 0.129470627 |

| Tibet | 0.379462971 | 0.341082291 |

| Guangdong | 0.1263666 | 0.069674881 |

| Guangxi | 0.23203989 | 0.154291944 |

| Hainan | 0.183161195 | 0.21864009 |

| Chongqing | 0.109231192 | 0.10294041 |

| Sichuan | 0.133879021 | 0.069311928 |

| Guizhou | 0.111019852 | 0.046034401 |

| Yunnan | 0.210180836 | 0.087600948 |

| Shaanxi | 0.252629845 | 0.192101563 |

| Gansu | 0.145947164 | 0.018582963 |

| Qinghai | 0.406716684 | 0.135911858 |

| Ningxia | 0.171183974 | 0.142737535 |

| Xinjiang | 0.132281933 | 0.102749751 |

| No. | Motif | Frequency | Z-Value | p-Value | No. | Motif | Frequency | Z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 |  | 32.24% | −2.57 | 1.00 | 14 |  | 10.60% | 2.62 | 0.00 |

| 38 |  | 5.02% | 2.54 | 0.00 | 174 |  | 6.66% | 2.25 | 0.02 |

| 36 |  | 0.18% | −1.58 | 0.86 | 46 |  | 32.90% | −2.88 | 1.00 |

| 12 |  | 0.37% | −3.44 | 1.00 | 78 |  | 0.37% | −1.54 | 0.88 |

| 238 |  | 11.28% | −0.51 | 0.66 | 102 |  | 0.37% | −1.71 | 0.93 |

| No. | Motif | Frequency | Z-Value | p-Value | No. | Motif | Frequency | Z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 |  | 23.21% | −1.02 | 0.85 | 14 |  | 13.46% | 0.91 | 0.19 |

| 38 |  | 10.13% | 0.62 | 0.26 | 174 |  | 9.17% | 0.27 | 0.39 |

| 140 |  | 0.27% | 0.64 | 0.22 | 166 |  | 0.67% | 2.78 | 0.01 |

| 36 |  | 1.10% | −1.53 | 0.94 | 46 |  | 26.16% | 0.75 | 0.22 |

| 12 |  | 3.32% | 1.48 | 0.07 | 78 |  | 0.88% | −2.56 | 1.00 |

| 238 |  | 9.43% | 2.62 | 0.02 | 102 |  | 1.80% | −2.44 | 0.99 |

| 164 |  | 0.40% | 0.49 | 0.26 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network Endogenous Structure | edges | 12.6152 *** (2.7133) | 11.5538 *** (2.6689) | 11.0675 *** (2.9659) | 2.4311 (6.7627) | 4.7519 (6.6310) |

| mutual (reciprocity) | 0.5805 * (0.2907) | 0.5911 (0.3187) | 1.7948 * (0.9087) | 1.8316 * (0.9038) | ||

| twopaths (connectivity) | −0.1093 * (0.0553) | −0.1722 (0.1060) | −0.1746 (0.1034) | |||

| ctriple (circularity) | 0.3154 *** (0.0742) | 0.6072 *** (0.1517) | 0.6115 *** (0.1502) | |||

| Outgoing Effects | gdp | −3.1557 *** (0.8173) | −4.3829 *** (1.0285) | −9.1874 *** (1.5144) | −19.2639 *** (3.3169) | −19.2774 *** (3.2671) |

| structure | −12.2324 *** (2.1773) | −12.0801 *** (2.2245) | −10.1689 *** (2.1806) | −20.2953 *** (4.8515) | −20.2603 *** (4.9086) | |

| resource | 5.9019 *** (0.8934) | 5.7504 *** (0.9162) | 4.5500 *** (0.9019) | 13.5485 *** (2.5933) | 13.6292 *** (2.5787) | |

| capacity | −1.2018 (0.6798) | −0.8932 (0.7125) | 0.7683 (0.7498) | −3.3827 * (1.6910) | −3.4279 * (1.6843) | |

| population | 2.3013 (1.2848) | 4.0346 ** (1.5611) | 10.7550 *** (2.1564) | 17.2771 *** (3.8602) | 17.2464 *** (3.7841) | |

| Incoming Effects | gdp | 16.1537 *** (1.0769) | 16.3912 *** (1.1069) | 17.7693 *** (1.1443) | 29.9450 *** (3.8471) | 29.9884 *** (3.7381) |

| structure | 0.2227 (2.1769) | 0.8446 (2.2567) | 4.7519 (2.4492) | 0.3096 (5.3247) | 0.1995 (5.3144) | |

| resource | 0.2358 (0.8134) | −0.1006 (0.8244) | −1.7133 (0.8889) | −29.9292 *** (3.7125) | −29.8308 *** (3.7789) | |

| capacity | −4.0020 *** (0.6975) | −3.9724 *** (0.6930) | −3.8680 *** (0.7118) | 16.0751 *** (2.5538) | 15.9728 *** (2.6104) | |

| population | −21.7727 *** (1.5306) | −22.0004 *** (1.5551) | −23.2980 *** (1.5873) | −20.4396 *** (4.0372) | −20.5900 *** (4.0185) | |

| Heterogeneity | gdp | 2.6821 *** (0.6583) | 2.5678 *** (0.6834) | 2.0949 ** (0.6373) | 3.3398 (1.7160) | 3.3749 * (1.6975) |

| structure | −3.1503 (2.6646) | −2.7498 (2.6102) | −2.5403 (2.5827) | −1.0136 (5.6924) | −1.0761 (5.6501) | |

| resource | 1.8435 ** (0.5694) | 1.9156 *** (0.5649) | 1.1106 (0.5898) | −0.4342 (1.5422) | −0.4084 (1.5171) | |

| capacity | −1.1580 * (0.4801) | −1.0952 * (0.4720) | −0.7201 (0.4722) | −1.2227 (1.1092) | −1.1900 (1.1005) | |

| population | −2.4687 ** (0.8640) | −2.4007 ** (0.8868) | −2.0065 * (0.8325) | −2.3084 (2.0525) | −2.3811 (2.0213) | |

| Time-Dependent effects | stability | 2.010594 *** (0.363592) | ||||

| innovation | −3.995436 *** (0.731878) | |||||

| Co-Network | geographic | −0.000500 *** (0.000130) | −0.000458 *** (0.000126) | −0.000372 ** (0.000123) | −0.000073 (0.000275) | −0.000066 (0.000279) |

| Num.obs | 1860 | 1860 | 1860 | 930 | 930 | |

| AIC | 1017.717503 | 2154.441794 | 2113.908187 | 256.325473 | 256.116727 | |

| BIC | 1111.699143 | 2266.725942 | 2238.668352 | 357.864349 | 357.655603 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Li, L.; Song, T.; Han, H. Study on the Evaluation and Driving Factors of Interprovincial Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer Under China’s Food Security Objective. Land 2026, 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010016

Wang Y, Sheng Y, Li L, Song T, Han H. Study on the Evaluation and Driving Factors of Interprovincial Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer Under China’s Food Security Objective. Land. 2026; 15(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yanan, Yu Sheng, Lihan Li, Tianhao Song, and Han Han. 2026. "Study on the Evaluation and Driving Factors of Interprovincial Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer Under China’s Food Security Objective" Land 15, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010016

APA StyleWang, Y., Sheng, Y., Li, L., Song, T., & Han, H. (2026). Study on the Evaluation and Driving Factors of Interprovincial Virtual Cultivated Land Risk Transfer Under China’s Food Security Objective. Land, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010016