Promoting Urban Ecosystems by Integrating Urban Ecosystem Disservices in Inclusive Spatial Planning Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can EDS be framed in terms of management actions needed to reconcile them with citizens’ needs and preferences within specific socio-ecological contexts?

- Is a universal approach to governing EDS feasible within inclusive planning frameworks?

- How does EDS management—understood as a structured process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating negative ecosystem impacts on human well-being while balancing ES and EDS in decision-making—interact with broader governance contexts?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the EDS Classification

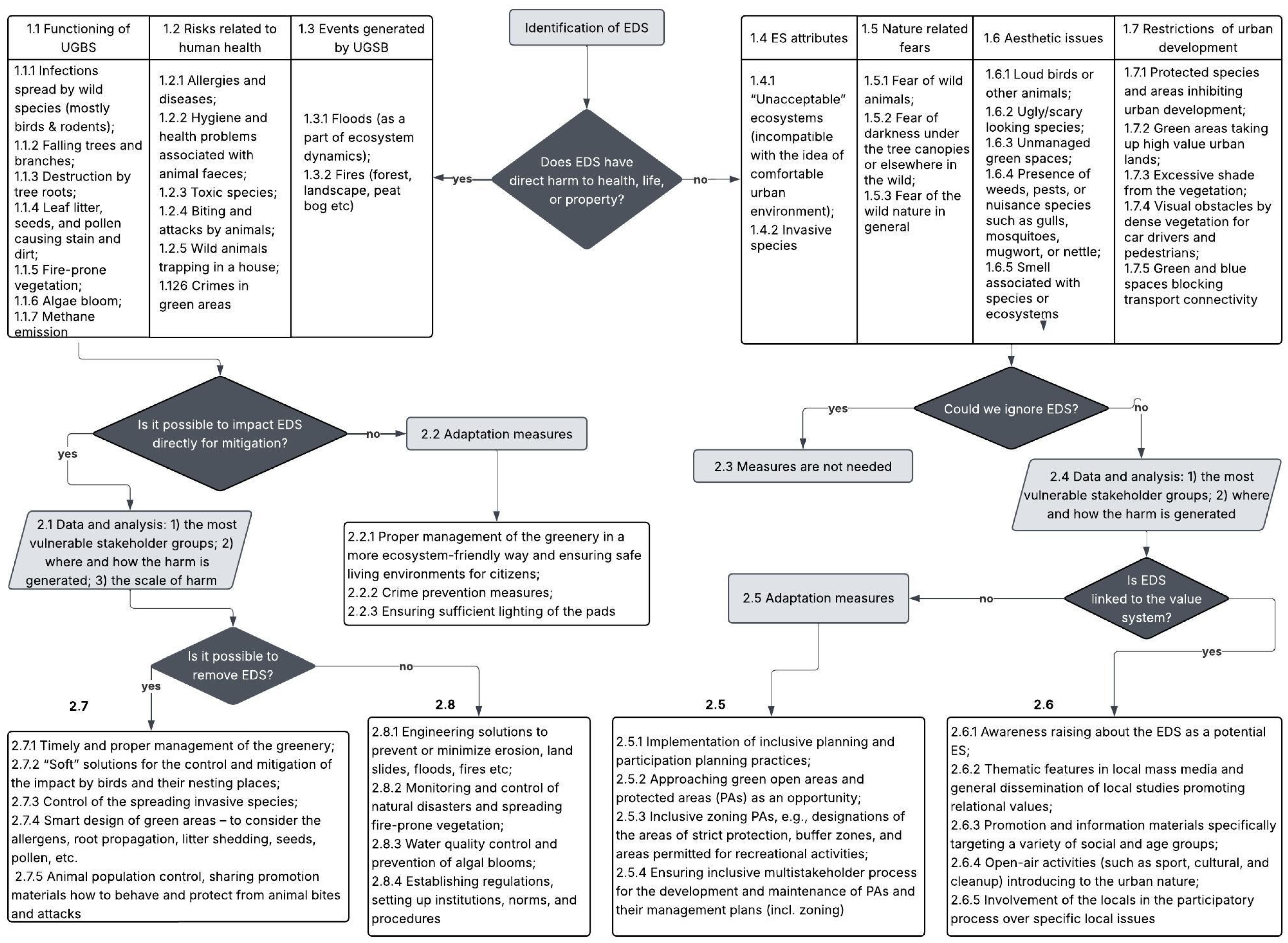

2.2. Construction of the Decision Tree

- the boundary between acceptable ecosystem dynamics and unacceptable EDS;

- prioritisation of biodiversity-friendly measures versus public safety;

- conditions under which non-engineering interventions are appropriate.

- four representative EDS cases (one from each major group) were jointly examined;

- participants navigated the draft tree step by step;

- feasibility, trade-offs, and contextual constraints were discussed;

- the tree was modified through consensus to reflect realistic ecological and governance conditions.

2.3. Application and Validation of the Framework in SES Contexts

3. Results

3.1. Estonian Cases

3.1.1. Situation E1: How Wild Nature in a City Became Decoupled from Poor Management Perceptions

3.1.2. Situation E2: How Cows in a City Became an Accepted Landscape Element

3.2. Belarusian Cases

3.2.1. Situation B1: What Opportunities for Mindset Transformation Are Worth Considering, but Were Not So Far

3.2.2. Situation B2: How Citizens Actively Resist When the Communication Was Not Convincing

3.2.3. Situation B3: How Adaptation of Mindsets Took Place, and What Hopes It Gives

3.3. Cross-Case Synthesis of Governance Conditions: Success Factors and Barriers

3.4. Broader SES Contexts of Action Situations: IAD Analysis

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. EDS Framing for Reconciling Them with the Needs and Preferences of Citizens

4.2. EDS-Aware Decision-Making for Inclusive Planning

4.3. Limitations and the Way Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDS | Ecosystem disservices |

| ES | Ecosystem services |

| EU | European Union |

| IAD | Institutional Analysis and Development (framework) |

| NBS | Nature-based solutions |

| SES | Socio-Ecological System |

References

- von Döhren, P.; Haase, D. Ecosystem disservices research: A review of the state of the art with a focus on cities. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki, L. Bad nature: Newspaper representations of ecosystem disservices. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, C.; Kendal, D.; Nitschke, C.R. Multiple ecosystem services and disservices of the urban forest establishing their connections with landscape structure and sociodemographics. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 43, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Kroeger, T.; Wagner, J.E. Urban forests and pollution mitigation: Analysing ecosystem services and disservices. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, A.; Kueffer, C.; Kull, C.; Richardson, D.; Vicente, J.; Kühn, I.; Schröter, M.; Hauck, J.; Bonn, A.; Honrado, J. Integrating ecosystem services and disservices: Insights from plant invasions. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 23, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisschemoller, M.; Kireyeu, V.; Freude, T.; Guerin, F.; Likhacheva, O.; Pierantoni, I.; Sopina, A.; von Wirth, T.; Scitaroci, B.; Mancebo, F.; et al. Conflicting perspectives on urban landscape quality in six urban regions in Europe and their implications for urban transitions. Cities 2022, 131, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Dendoncker, N.; Barnaud, C.; Sirami, C. Ecosystem disservices matter: Towards their systematic integration within ecosystem service research and policy. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 36, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyra, M.; La Rosa, D.; Zasada, I.; Sylla, M.; Shkaruba, A. Governance of ecosystem services trade-offs in peri-urban landscapes. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 10461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkaruba, A.; Skryhan, H.; Likhacheva, O.; Katona, A.; Maryskevych, O.; Kireyeu, V.; Sepp, K.; Shpakivska, I. Development of sustainable urban drainage systems in Eastern Europe: An analytical overview of the constraints and enabling conditions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 2435–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Hinchman, L. The Theory of Social Democracy; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2007; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Van Herzele, A.; Wiedemann, T. A monitoring tool for the provision of accessible and attractive urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Vink, M.; Warner, J.; Winnubst, M. Watered-down politics? Inclusive water governance in the Netherlands. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 150, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuken, Y.R.H.; Breukers, S.; Sari, R.; Rugani, B. Nature 4 Cities: Nature Based Solutions: Projects Implementation Handbook; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://55d29d92-2db4-4dd3-86b5-70250a093698.usrfiles.com/ugd/55d29d_58487570de4147d38035351ba5b61a69.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Schaubroeck, T. A need for equal consideration of ecosystem disservices and services when valuing nature; countering arguments against disservices. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C.; Coley, R.L.; Brunson, L. Fertile ground for community: Inner-city neighborhood common spaces. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1998, 26, 823–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 60, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. Making a difference on the ground: The challenge of demonstrating the effectiveness of decision support. Clim. Change 2009, 95, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, r1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.; Elbakidze, M.; Schellens, M.; Shkaruba, A.; Angelstam, P.K. Bogs, birds, and berries in Belarus: The governance and management dynamics of wetland restoration in a state-centric, top-down context. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew-Smythe, J.J.; Davila, Y.C.; McLean, C.M.; Hingee, M.C.; Murray, M.L.; Webb, J.K.; Krix, D.W.; Murray, B.R. Community perceptions of ecosystem services and disservices linked to urban tree plantings. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, S.; Haase, A.; Andersson, E.; Banzhaf, E.; Baró, F.; Brenck, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; et al. Greening cities–To be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, S.; Van de Voorde, T. Which environmental features contribute to positive and negative perceptions of urban parks? A cross-cultural comparison using online reviews and Natural Language Processing methods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 218, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Rosales Chavez, J.B.; Brown, J.A.; Morales-Guerrero, J.; Avilez, D. Human–wildlife interactions and coexistence in an urban desert environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbroek, B.; de Kraker, J.; Huynen, M.M.; Martens, P.; Verhoeven, K. Assessment of green space benefits and burdens for urban health with spatial modeling. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwik, A.; Wójcik, T.; Ziaja, M.; Wójcik, M.; Kluska, K.; Kasprzyk, I. Ecosystem services and disservices of vegetation in recreational urban blue-green spaces—Some recommendations for greenery shaping. Forests 2021, 12, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryhan, H.; Shkaruba, A. Reconciling Cities with Urban Nature: Towards the Integration of Ecosystem Disservices in Inclusive Spatial Planning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovation in Urban and Regional Planning, Catania, Italy, 8–10 September 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veibiakkim, R.; Shkaruba, A.; Sepp, K. A systematic review of urban ecosystem disservices and its evaluation: Key findings and implications. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analysing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinnis, M.D. Networks of adjacent action situations in polycentric governance. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmich, C.; Baldwin, E.; Kellner, E.; Oberlack, C.; Villamayor-Tomas, S. Networks of action situations: A systematic review of empirical research. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, P.-J.; Denters, S. Structuring Participatory Governance through Particular ‘Rules in Use’: Lessons from the Empirical Application of Elinor Ostrom’s IAD Framework. In Handbook on Participatory Governance; Heinelt, H., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryhan, H.; Shkaruba, A.; Lichaczeva, O. Ecosystem disservices in inclusive urban planning—The case of Mahiliou (Belarus). Pskov. Reg. Stud. J. 2022, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Printsmann, A.; Nugin, R.; Palang, H. Intricacies of moral geographies of land restitution in Estonia. Land 2022, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkaruba, A.; Skryhan, H.; Kireyeu, V. Sense-making for anticipatory adaptation to heavy snowstorms in urban areas. Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Jensen, A.; Raagmaa, G. Restitution of agricultural land in Estonia: Consequences for landscape development and production. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2010, 64, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lategan, L.; Steynberg, Z.; Cilliers, E.; Cilliers, S. Economic valuation of urban green spaces across a socioeconomic gradient: A South African case study. Land 2022, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.J.; Allcock, A.L.; Bates, A.E.; Firth, L.B.; Smith, I.P.; Swearer, S.; Evans, A.; Todd, P.; Russell, B.; McQuaid, C. (Eds.) Oceanography Marine Biology An Annual Review; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; Volume 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, A.; Panno, A.; Agrimi, M.; Masini, E.; Carrus, G. Can we barter local taxes for maintaining our green? A psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 816217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y. A bibliometric and visualization review analysis of agricultural ecosystem services research. Low Carbon Econ. 2022, 13, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, D.; Hynes, S.; Buckley, C.; Ryan, M.; Doherty, E. An initial catchment level assessment of the value of Ireland’s agroecosystem services. Biol. Environ. Proc. R. Ir. Acad. 2020, 120B, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.; Bachi, L.; Blanco, J.; Zimmermann, I.; Welle, I.; Ribeiro, S. Perceived ecosystem services (ES) and ecosystem disservices (EDS) from trees: Insights from three case studies in Brazil and France. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1583–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Arellano, C.; Mulligan, M. A review of regulation ecosystem services and disservices from faunal populations and potential impacts of agriculturalisation on their provision, globally. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 30, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilvits, C.; Suškevičs, M.; Napp, M.; Ojaste, I.; Edovald, T.; Roasto, R.; Tammekänd, E.; Külvik, M. No Single Story: Exploring the viewpoints of Estonian environmental civil servants on citizen science with Q-methodology. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.; Elbakidze, M.; van Ermel, L.K.; Olsson, U.; Ongena, Y.P.; Schaffer, C.; Johansson, K.E. Why don’t we go outside?–Perceived constraints for users of urban greenspace in Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Zardo, L.; Maragno, D.; Musco, F.; Burkhard, B. Let’s Do It for Real: Making the ecosystem service concept operational in regional planning for climate change adaptation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liski, A.H.; Koetse, M.J.; Metzger, M.J. Addressing awareness gaps in environmental valuation: Choice experiments with citizens in the Inner Forth, Scotland. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 2217–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirfan, L.; Peck, M. Deliberative Q-method: A combined method for understanding the ecological value of urban ecosystem services and disservices. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hérivaux, C.; Coënt, P. Introducing nature into cities or preserving existing peri-urban ecosystems? Analysis of preferences in a rapidly urbanizing catchment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EDS Group | EDS Sub-Group | EDS Examples |

|---|---|---|

| I. Ecosystem attributes and functions | Ia. Ecosystem attributes | Ecosystems perceived as “unacceptable” (e.g., wetlands), invasive species |

| Ib. Events arising from ecosystem dynamics | Flooding as part of ecosystem dynamics; wildfires (forest, landscape, peatland) | |

| Ic. Functioning of urban ecosystems | Infections and pathogens spread by wild species; falling trees and branches; invasive roots damaging infrastructure; leaf litter; seeds and pollen; fire-prone vegetation; algal blooms, etc. | |

| II. Human health | IIa. Risks related to human health | Allergies and diseases; hygiene and public-health concerns; toxic species; biting insects/animals; attacks by wild animals; crime and safety risks in green areas |

| IIb. Nature related fears | Fear of wild animals; fear of darkness in green spaces; fear or avoidance of “wild” nature in general | |

| III. Aesthetic and sensory disturbances | Non applicable | Loud calls/sounds of birds, dogs, etc.; unattractive or frightening species; poorly maintained or unmanaged green spaces; weeds, pests, or nuisance species; unpleasant odours |

| IV. Constraints on urban development | Non applicable | Protected species and areas constraining urban development; land-use restrictions reducing property values; barriers to transport connectivity; excessive shading or visual obstruction caused by vegetation |

| Mahilioŭ | Pärnu | Tartu | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical coordinates | 53°55′ N 30°21′ E | 58°23′05″ N 24°31′07″ E | 58°23′ N 26°43′ E |

| Year of foundation or first mentioned | 1267 | 1251 | 1030 |

| Area, km2 | 118.5 | 33.15 | 38.9 |

| Elevation (mean/max/min/range), m | 171/210/138/72 | 5/21/−2/23 | 55/82/27/55 |

| Green (tree, shrub) areas, km2/% | 15.9/13.5 | 6.4/19.3 | 39.8/25.8 |

| Type of climate (Köppen) | humid continental Dfb | humid continental Dfb | humid continental Dfb |

| Average daily mean temperature, °C | 6 | 8.8 | 8.1 |

| Average annual precipitation, mm | 622 | 678 | 587 |

| Population | 383,313 | 40,253 | 98,247 |

| The biggest ethnic group & % of total population | Belarusians, 91% | Estonians, 83.7% | Estonians, 80.1% |

| Element | Content |

|---|---|

| Urban nature/intervention | “Curated Biodiversity” project (2020–): low-mow meadows, micro-wetlands, insect-friendly habitats, pocket parks, native planting beds, art-based park installations. |

| Key ES at stake | Biodiversity and habitat support; regulating ES (cleaner air, soil, and water); cultural ES (recreation, learning, place quality). |

| Key EDS types (classification link) | Aesthetic/sensory discomfort from “unmanaged” appearance (Group III/1.6); nature-related fears regarding ticks/insects/Spanish slug (Group IIb/1.5). |

| EDS manifestations | Complaints about tall grass and perceived neglect; concern about higher tick/insect occurrence and invasive slugs. |

| Actively involved stakeholders | City officials and project leaders; residents/park users; local media; art students/community participants. |

| Main conflict/tension | Biodiversity-based “wild” aesthetics vs. expectations of tidy lawns; fear of nuisances vs. ecological rationale. |

| Decision-making tree pathway applied | Communication and engagement measures to reframe perceptions and build acceptance (steps 2.6.1–2.6.4). |

| Outcome (type) | EDS concerns addressed through communication; management pathway follows the decision-making tree; ecosystem/NBS maintained. |

| Decisive factors | Early identification of perceived EDS; clear on-site explanations; sustained outreach (social media, press, events); participatory planting fostering ownership. |

| Element | Content |

|---|---|

| Urban nature/intervention | Restoration of Pärnu coastal meadows via LIFE projects (2012–2016+) with ongoing Highland cattle grazing; boardwalk, trails, birdwatching towers; hydrological restoration and reed/shrub removal. |

| Key ES at stake | Conservation of endangered Baltic coastal meadows; habitat for protected species; regulating ES (hydrological functioning, reed control); cultural ES (recreation, tourism, education). |

| Key EDS types (classification link) | Health/safety EDS: feces-related water-quality risk; potential cattle bites (Group IIa/1.2). Aesthetic/sensory EDS: odour and noise (Group III/1.6). |

| EDS manifestations | Visitor concerns about beach water pollution; fear of bites when people approach/feed cows; minor effects from odour/noise. |

| Actively involved stakeholders | Municipal government; farmers providing cattle; residents and beach visitors; ecologists/conservation bodies. |

| Main conflict/tension | Need for grazing to sustain habitats vs. perceived health/safety risks and discomfort in a recreational beach setting. |

| Decision-making tree pathway applied | Non-negotiable risks → monitoring/regulatory safeguards (2.8.3). Manageable risks → preventive signage (2.7.5). Minor aesthetic EDS → tolerance with monitoring (2.3). |

| Outcome (type) | Adaptive management consistent with the decision-making tree; grazing continues and ecosystem is maintained. |

| Decisive factors | Ecological necessity of grazing; separation of non-negotiable vs. manageable EDS; legal water-quality monitoring; targeted communication to visitors. |

| Element | Content |

|---|---|

| Urban nature/intervention | Dubravenka River floodplain (wetlands, oxbows, ponds) adjacent to housing; future management/development options under debate. |

| Key ES at stake | Biodiversity and habitat value; regulating ES (floodplain dynamics, microclimate, climate resilience); cultural ES potential (learning, recreation, nature experience). |

| Key EDS types (classification link) | Local nuisance and access-related disservices: insects, odours, fog, dirt, poor connectivity; marginalisation and unmanaged aesthetics (Groups I/III; 1.4.1, 1.6.3–1.6.5). |

| EDS manifestations | Residents perceive the area as unpleasant and neglected; annoyance is strongest among those living adjacent to the floodplain. |

| Actively involved stakeholders | Adjacent residents; wider city public; municipal planners; potential developers; ecologists/experts. |

| Main conflict/tension | Pressure for “improved/tidy” public space and development vs. maintaining dynamic wetland ecosystem and biodiversity. |

| Decision-making tree pathway considered | Communication to shift perceptions and values (2.6); acceptance-building and minor improvements for access/safety (2.5); focus on most affected local groups (2.4). |

| Outcome (type) | Situation remains open; decision-making tree used as a structured deliberation tool to explore ecosystem-friendly alternatives. |

| Decisive factors | Loss of traditional uses weakened ES recognition; strong localised EDS perception; resource constraints; tree-guided discussion prompted preference change among several interviewees. |

| Element | Content |

|---|---|

| Urban nature/intervention | Small constructed wetland and oil trap for stormwater purification at ravine outlet (NGO project, 2015–2017). |

| Key ES at stake | Regulating ES (water purification, runoff treatment); potential cultural ES (cleaner ravine landscape, local amenity). |

| Key EDS types (classification link) | Primarily perceived aesthetic/nuisance EDS: fear of odours, insects, unsightly views, and “treatment facility” stigma (Group III/1.6.4–1.6.5). |

| EDS manifestations | Residents interpreted the project as a “water treatment plant”; anxiety about pollution and nuisance effects; opposition escalated politically. |

| Actively involved stakeholders | Local cottage residents; NGO implementers; municipal authorities; mayor/political level. |

| Main conflict/tension | Top-down NBS introduction vs. strong local risk perception and low trust; environmental benefits vs. short-term political avoidance of conflict. |

| Decision-making tree pathway that would apply | Early intensive communication, co-framing, and institutionalisation to address aesthetic fears (2.6.1 and 2.6.5). |

| Outcome (type) | Management pathway diverged from decision-making tree logic; project halted by mayoral order. |

| Decisive factors | Inadequate early communication; stigma around “treatment” narrative; weak trust; political override prioritising short-term stability. |

| Element | Content |

|---|---|

| Urban nature/intervention | Piačersk Woods: historical city forest with intensive recreation; long-term NGO/academic initiative to establish protected area (process intensified 2000s–2018+). |

| Key ES at stake | Biodiversity conservation (red-listed species, habitat mosaic); regulating ES (urban forest functions); cultural ES (recreation, identity, education). |

| Key EDS types (classification link) | Perceived restrictions and fears linked to protection status and “wild” forest (categories 1.5.3, 1.7.1, 1.7.2). |

| EDS manifestations | Initially low recognition of conservation value; concern that protection would limit use or development. |

| Actively involved stakeholders | NGO activists; academics; concerned residents; small businesses; journalists; municipal planners; National Academy of Sciences experts. |

| Main conflict/tension | Conservation and protection regime vs. expectations of unrestricted recreation and/or development opportunities. |

| Decision-making tree pathway applied | Extended values/awareness work and coalition building (2.6.1–2.6.4), followed by institutionalisation and agenda-setting (2.6.5). |

| Outcome (type) | Management trajectory follows decision-making tree logic; municipality initiated formal process to establish a protected area. |

| Decisive factors | Long-term multi-actor coalition; repeated engagement events; expert confirmation of biodiversity value; gradual shift in public and municipal perceptions. |

| Feature | Estonia (Situations E1, E2: Successful Trajectories) | Belarus (Situations B1, B2, B3: Mixed Trajectories) |

|---|---|---|

| Communication & Framing | Proactive, sustained, and explanatory. Focused on articulating the ecological rationale and expected benefits early on. Communication was targeted (e.g., clear safety guidance/signage). | Varied, but often non-credible or inadequate in failed cases. Poor communication led to negative reinterpretation (e.g., “treatment facility” stigma). Success (B3) required extended values/awareness work. |

| Institutional Embedding & Conflict | Supported by stable institutional arrangements capable of sustaining management over time. Management adhered to decision-making logic, distinguishing between non-negotiable risks (requiring monitoring/safeguards) and manageable risks. | Unsuccessful cases (B1, B2) had insufficient institutional embedding for EDS negotiation. Projects were vulnerable to short-term political override (e.g., mayoral order) despite environmental logic. Success (B3) required obtaining expert validation and forming a dedicated committee to anchor the process in formal governance. |

| Stakeholder Engagement & Trust | Focused on meaningful, low-threshold engagement that fostered familiarity and shared responsibility (e.g., participatory planting). Engagement built legitimacy and trust. | Often characterized by low initial trust. Successful outcomes (B3) relied on building a long-term multi-actor coalition and repeated engagement events to gradually shift public and municipal perceptions. Failure occurred when top-down attempts were met with strong local resistance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shkaruba, A.; Skryhan, H.; Külm, S.; Sepp, K. Promoting Urban Ecosystems by Integrating Urban Ecosystem Disservices in Inclusive Spatial Planning Solutions. Land 2026, 15, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010012

Shkaruba A, Skryhan H, Külm S, Sepp K. Promoting Urban Ecosystems by Integrating Urban Ecosystem Disservices in Inclusive Spatial Planning Solutions. Land. 2026; 15(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleShkaruba, Anton, Hanna Skryhan, Siiri Külm, and Kalev Sepp. 2026. "Promoting Urban Ecosystems by Integrating Urban Ecosystem Disservices in Inclusive Spatial Planning Solutions" Land 15, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010012

APA StyleShkaruba, A., Skryhan, H., Külm, S., & Sepp, K. (2026). Promoting Urban Ecosystems by Integrating Urban Ecosystem Disservices in Inclusive Spatial Planning Solutions. Land, 15(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010012