1. Introduction

The introduction cities are extremely dynamic settlement units that undergo numerous rebuilding and adaptation to the needs of the inhabitants, one of which is the need to bury the dead [

1,

2]. In this way, cemeteries are one of those elements of cities that were and still are integral parts of cities. If we look at the history of their formation and location within cities, we can see two main stages. The first of these is the placement of cemeteries next to churches, which meant that cemeteries were placed next to each church, often in central parts of cities, in close proximity to tenement houses and fairgrounds [

3,

4]. In turn, in the second half of the 18th century, the cemeteries were moved to the outskirts of the cities of that time, because the space occupied by the church cemeteries could be used for other purposes [

5]. What is more, the vicinity of the cemeteries began to be associated with an epidemiological threat [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Despite the fact that the cemeteries were built on the outskirts of cities in the second half of the 18th century, currently they constitute an important element of the urban space in central areas of cities [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, the question remains how they should be treated and whether they have natural, historical, and recreational values in the opinion of the inhabitants [

2,

17,

18,

19].

Today, more than ever, cemeteries play a key role in promoting sustainable development and social well-being in line with the United Nations’ seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is not only about the use of natural resources and the way green areas and tombstones are maintained but also about the broader context of cultural changes in terms of more sustainable funeral practices and creating cemeteries of the future that are a resting place for the deceased and a place to spend time for the living [

1,

20,

21].

The consequences of climate change in European cities are becoming more and more noticeable every year. Snowstorms and floods are becoming more frequent and require ongoing infrastructure repairs, which are very costly, placing additional, unforeseen expenses on cities. Long periods of drought and periodic water shortages due to the lack of water retention, especially in the summer and fall, cause trees and shrubs to die, contributing to an increase in air temperature and a decrease in humidity [

22,

23].

Despite being classified as urban green spaces, cemeteries are rarely considered in the context of climate change and determining the potential of green infrastructure.

We will say that this phenomenon is the failure to consider cemeteries as potential recreational areas, but rather as places with a unique history and their own ecological niche for people seeking peace of mind and tranquility [

24].

These areas, once built as green spaces, are now increasingly becoming “deserts” with concrete graves and paved alleys. These phenomena are also often accompanied by the cutting down of old and valuable trees. These actions cause cemeteries to be included (although fortunately they are not) in the balance of built-up areas rather than in the areas that make up the biologically active surface.

Therefore, new research on urban green infrastructure, and our own, should pay more attention to their natural and recreational significance in the context of climate change by introducing sustainable elements of urban green infrastructure (UGI), both vegetation and ecological equipment, as well as small architecture.

The purpose of the paper is to get to know the opinions of the young generation that are shaping the trends of the future UGI. We are interested in how they perceive cemetery space in the context of urban green spaces in terms of climate change and recreational needs. Therefore, during our research, we would like to answer four main research questions:

What are the differences between cemeteries and other urban green spaces?

Are there any differences in spatial layout and landscape design between cemeteries in Berlin and Warsaw?

Can cemeteries be considered as potential recreational areas?

What are the challenges of developing cemeteries for the needs of urban green infrastructure (UGI) in the context of climate change?

In order to answer those questions, we study specific socio-ecological potential and find ecological functions of the cemeteries (e.g., climate regulation, habitat sphere, green corridors, etc.) by questionnaire survey analysis. A study of cemeteries can reveal the specific group of population that, in order to find a significant difference among those groups, use other green spaces within the city.

Case Study

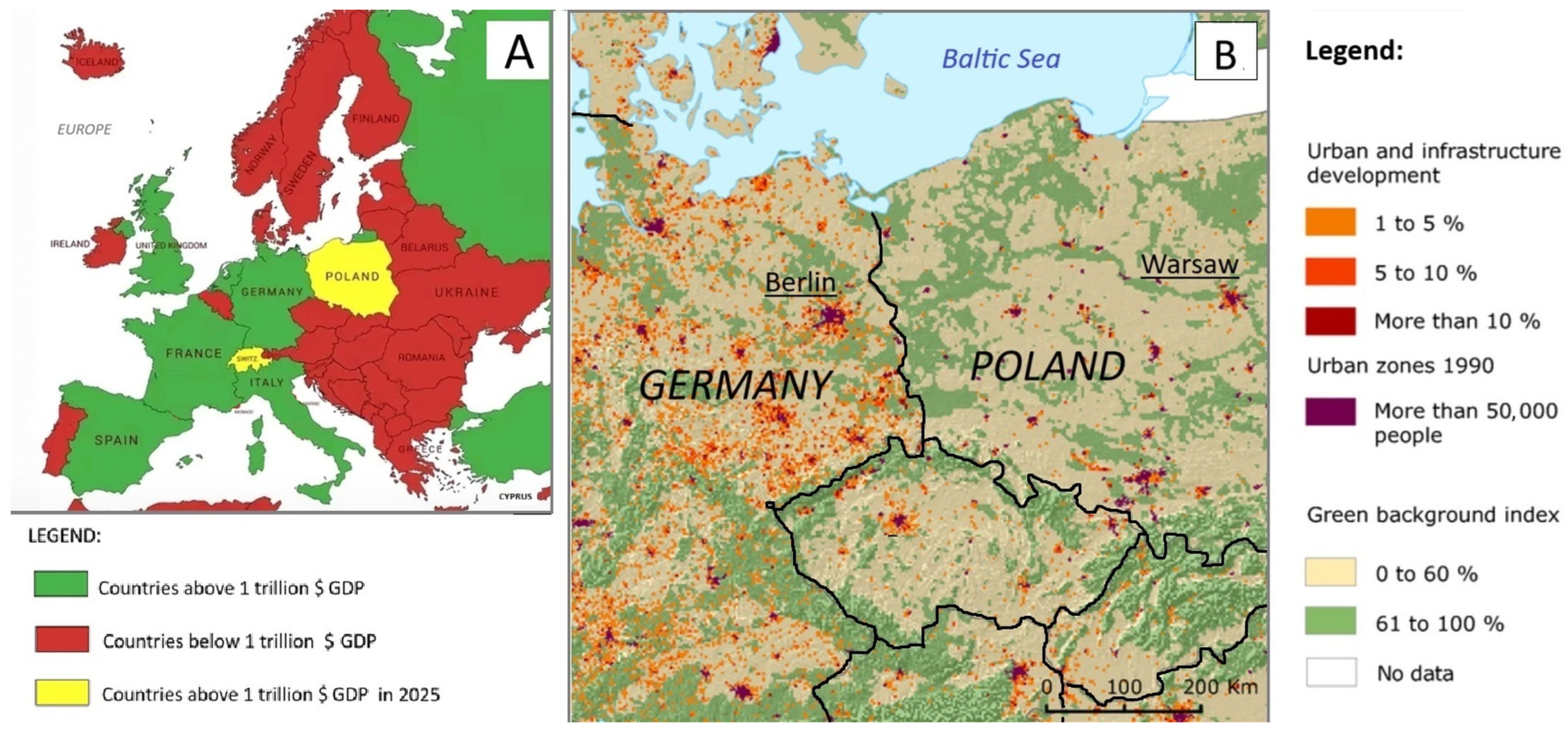

We observe the opinion of perception of the cemeteries in two capitals in Central Europe—Warsaw (Poland) and Berlin (Germany) [

25,

26]. Why were these cities chosen? Because as capitals after the Second World War, they were heavily destroyed. In spite of this, for Warsaw this fact is well-known, especially for Poles [

27,

28,

29]; for Berlin, rather not, because since 1944, the capital of Germany has been destroyed by British raids [

30,

31]. However, both cities were rebuilt, and then they were subject to significant development, both in the sense of development and the inclusion of further districts [

32,

33]. What is more, both capitals were multicultural cities; hence, the diversity of religious cemeteries is also present in these cities [

24,

34]. The cemeteries of those cities show their history, which is still visible today when young people visit the cemetery [

35]. Thus, this issue and the importance of these places as capitals of high GBK and climate change aspects due to El Niño and La Niña for the young generation seem particularly important to us (

Figure 1A).

Two large cities (capitals) of Central Europe, Warsaw and Berlin (

Figure 1B), are characterized by a multi-national (Poles, Germans, Jews, Russians, Turks, etc.) and multi-confessional (Catholicism, Evangelism, Judaism, Orthodox Christianity, Islam, etc.) past, and the history of well-developed and dense cities is reflected in their old cemeteries (

Figure 2). Where the cultural, religious, and touristic functions of urban cemeteries are well defined, the ecological and environmental importance of these areas are less recognized, maybe because cemeteries are not always considered as possessing essential elements of UGI, like for instance, parks, street trees, or green roofs [

36]. A review of the relevant literature confirms that urban cemeteries have not yet been extensively explored in ecological and environmental respects. Recently, however, urban cemeteries are increasingly gaining in importance as “ecological reserve areas” for branches of science dealing with urban planning and ecology.

2. Materials and Methods

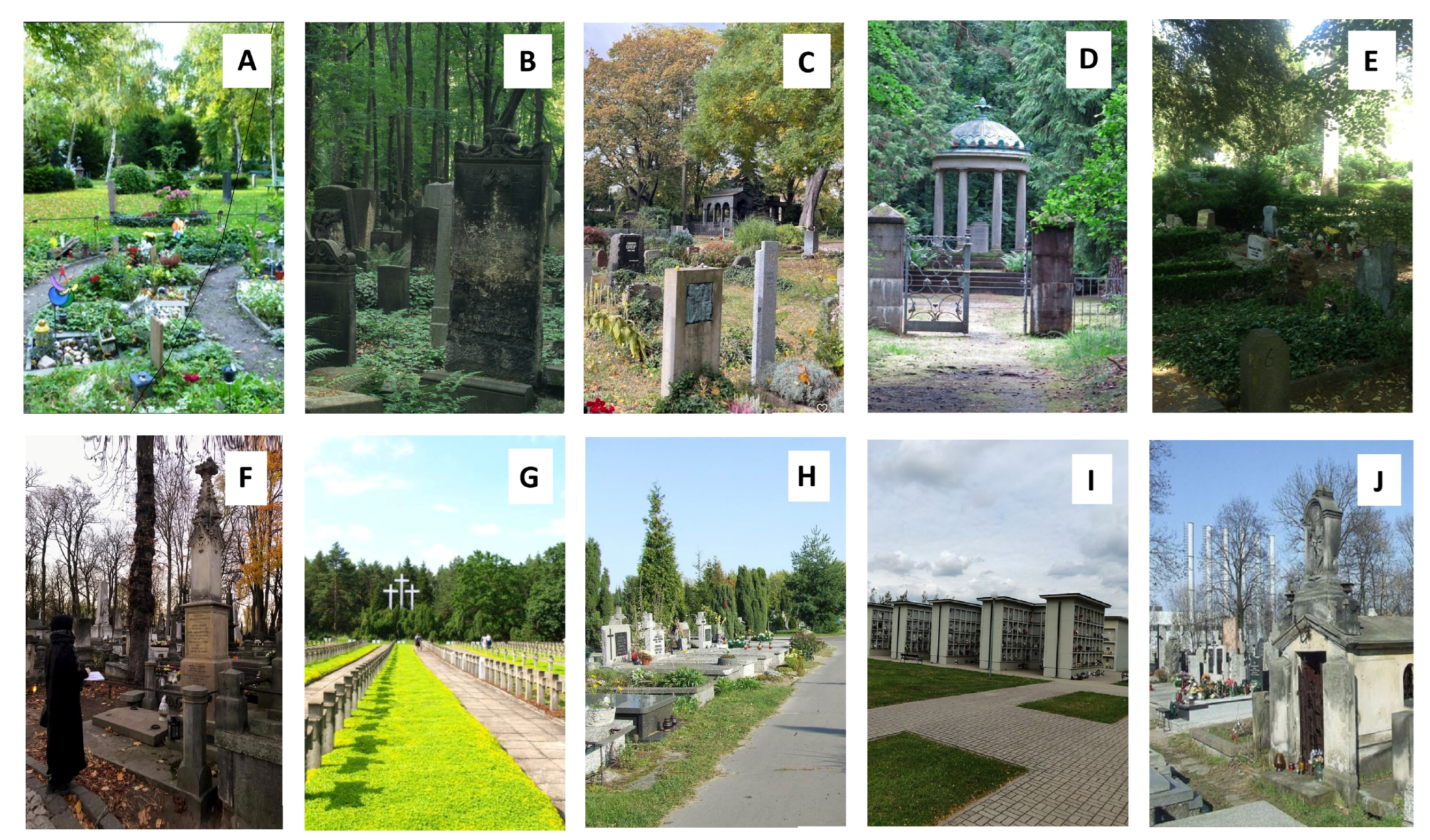

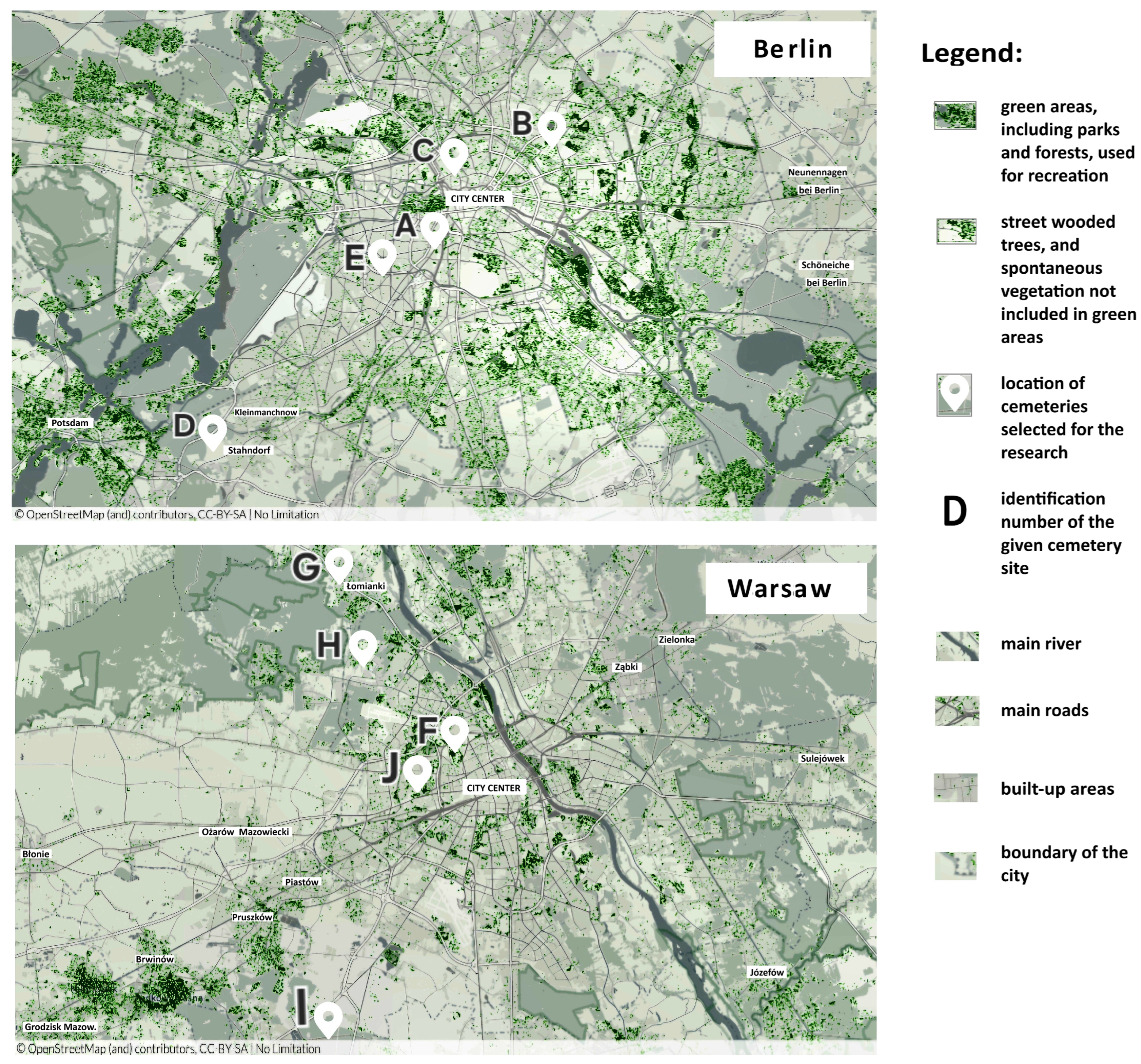

For the research, we selected 5 cemeteries in Berlin (Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof, Jewish Cemetery Weißensee, Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf, Friedhof Schöneberg III), and 5 in Warsaw (Powązki, Palmiry, Cmentarz Północny, Cmentarz Południowy, Cmentarz Wolski) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). All cemeteries selected are mostly visited in the city and are different in terms of usage, confession, and function. In our research, we used a multi-mixed method that combines various analyses from the fields of interdisciplinary urban ecology, landscape architecture, sociology, and spatial planning [

36]. These analyses are as follows:

Analysis of the selection of cemeteries for research according to specific selection criteria: location in the city, type of religion, green coverage, valuable tree stands, and historical monuments listed in the local register of protected areas;

Analysis in terms of resilience and adaptation to climate change;

Analysis of the management and planning related to the cemeteries in Poland and Germany;

Questionnaire survey with a statistical analysis (chi-square test) [

37].

Figure 3.

Cemeteries selected for the research. Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof (A); Jewish Cemetery Weißensee (B); Dorotheenstadt Cemetery (C); Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf (D); Friedhof Schöneberg III (E); Powązki (F); Palmiry (G); Cmentarz Północny (H); Cmentarz Południowy (I); Cmentarz Wolski (J). Locations (A–E)—Berlin (Germany), (F–J)—Warsaw (Poland). Photographs: A.Długoński.

Figure 3.

Cemeteries selected for the research. Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof (A); Jewish Cemetery Weißensee (B); Dorotheenstadt Cemetery (C); Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf (D); Friedhof Schöneberg III (E); Powązki (F); Palmiry (G); Cmentarz Północny (H); Cmentarz Południowy (I); Cmentarz Wolski (J). Locations (A–E)—Berlin (Germany), (F–J)—Warsaw (Poland). Photographs: A.Długoński.

A questionnaire survey (

Supplementary Materials S1) and statistical analysis (chi-square test) were chosen as the research method to find the answers among the young generation of Polish and German students residing in selected cities (capitals) with a population of over 50,000 (

Figure 1B). A total of 213 respondents completed the questionnaire/online survey, including 96 residents of Berlin and 117 residents of Warsaw. The age of the subjects ranged from 19 to 70 years, with an average of 24.6 years. Residents of these cities were selected for the study due to the fact that historic or partially historic cemeteries function within the central parts of these cities.

Table 1 lists the questions answered by the respondents. The research group of students within the established age range was selected because it is the most representative. The younger generation will shape the trend of green infrastructure development. Older people responded less frequently, and their opinions on the potential of cemeteries are more conservative and boil down to perceiving cemeteries mainly as a sphere of the sacred. Based on our previous research conducted among users in Leipzig (Germany) and Lodz (Poland), we noticed that young people more often choose the possibility of recreation as an alternative to rest. Therefore, we wanted to repeat this test in the European capitals of these countries [

36,

37].

In our research, a statistical analysis (chi-square test) was performed [

37]. According to this test, a value of 0.05 is assumed to be the cut-off and determines the statistical significance of a given research question. The studies were carried out in the statistical program Statistica 13.1 [

39]. The data were collected in the period June 2022–March 2023 among the young generation of students at Warsaw and Berlin universities [

38].

3. Results

Both in Poland and Germany, cemeteries are often included in typologies of green infrastructure features, but there has been little exploration of their role within a multifunctional network of green infrastructure [

40]. This is due to the fact that cemeteries differ from other green spaces in terms of the degree of vegetation coverage due to the graves and the potential for recreation. While areas like parks or city squares can offer a full range of passive and active recreation, cemeteries can be seen as places of rest, peace, and contemplation. However, this does not mean that we cannot talk about passive recreation in the context of a cemetery, such as walking, watching movies, or reading books. We observed these activities at German cemeteries, as cemeteries are treated partly as parks, which is a result of German culture and tradition [

41].

Of the total of 222 Berlin cemeteries, with an indicator of 0.06 (number of residents per 1000 inhabitants), 185 are open. The State of Berlin administers 85 cemeteries at present, 2 of which are located in the surrounding areas. Approx. 580 ha of state-owned cemetery space is located within the boundaries of Berlin. The administration is carried out at the borough level, by the departments of green spaces, or the relevant special offices of the particular boroughs. The remaining cemeteries are operated by the legally independent church communities of the various denominations. Most denominational cemeteries are the property of the Protestant church communities, which maintain 118 cemeteries covering a total of approximately 411 ha within Berlin. Two cemeteries of Berlin Protestant churches are also located in the surrounding areas. Moreover, there are nine Catholic cemeteries covering 48 ha, five Jewish cemeteries, one Russian-Orthodox cemetery, one Muslim cemetery, one British cemetery, and two other cemeteries [

42].

Of the total of 40 cemeteries with an indicator of 0.02 (number of cemeteries per 1000 inhabitants), 31 are open [

43]. The state of Warsaw administers six cemeteries at present, two of which are located in the suburban areas. Approx. 385.6 ha of state-owned cemetery space is located within the boundaries of Warsaw. The administration is carried out at the borough level, by the departments of green spaces, or the relevant special offices of the particular boroughs.

The remaining cemeteries are operated by the legally independent church communities of the various denominations (Orthodox, Protestant, Jewish, and Muslim). Most denominational cemeteries are the property of the Catholic church communities, which maintain 17 cemeteries covering a total of approximately 218.2 ha within Warsaw. Four cemeteries of Warsaw War Memory are also located in the city of Warsaw. Moreover, there are two Protestant cemeteries covering 9.3 ha, two Muslim cemeteries, one Jewish cemetery, one Orthodox cemetery, and other cemeteries with uncommon status [

44].

In terms of cemetery materials and infrastructure, we can mainly see old-style concrete or asphalt pavement. Other equipment elements, such as streetlights, benches, trash cans, water taps, and railings, are also made of concrete, steel, or plastic, and sometimes have low aesthetic value. Over time, they undergo increasing oxidation and lose the properties of these materials.

The existing vegetation on cemeteries in Poland and Germany can be attributed to the following species: small-leaved linden (

Tilia cordata), Crimean linden (

Tilia euchlora), horse chestnut (

Aesculus sp.), bird cherry (

Prunus avium), silver spruce (

Picea pungens), Norway maple (

Acer platanoides), arborvitae (

Thuja sp.), European ash (

Fraxinus excelsior), planted in alleys or individually, as well as common ivy (

Hedera helix), common hornbeam (

Carpinus betulus), and common yew (

Taxus baccata) in hedges [

10,

24,

36,

42,

44,

45,

46]. This is the typical vegetation of the temperate subtropical climate zone.

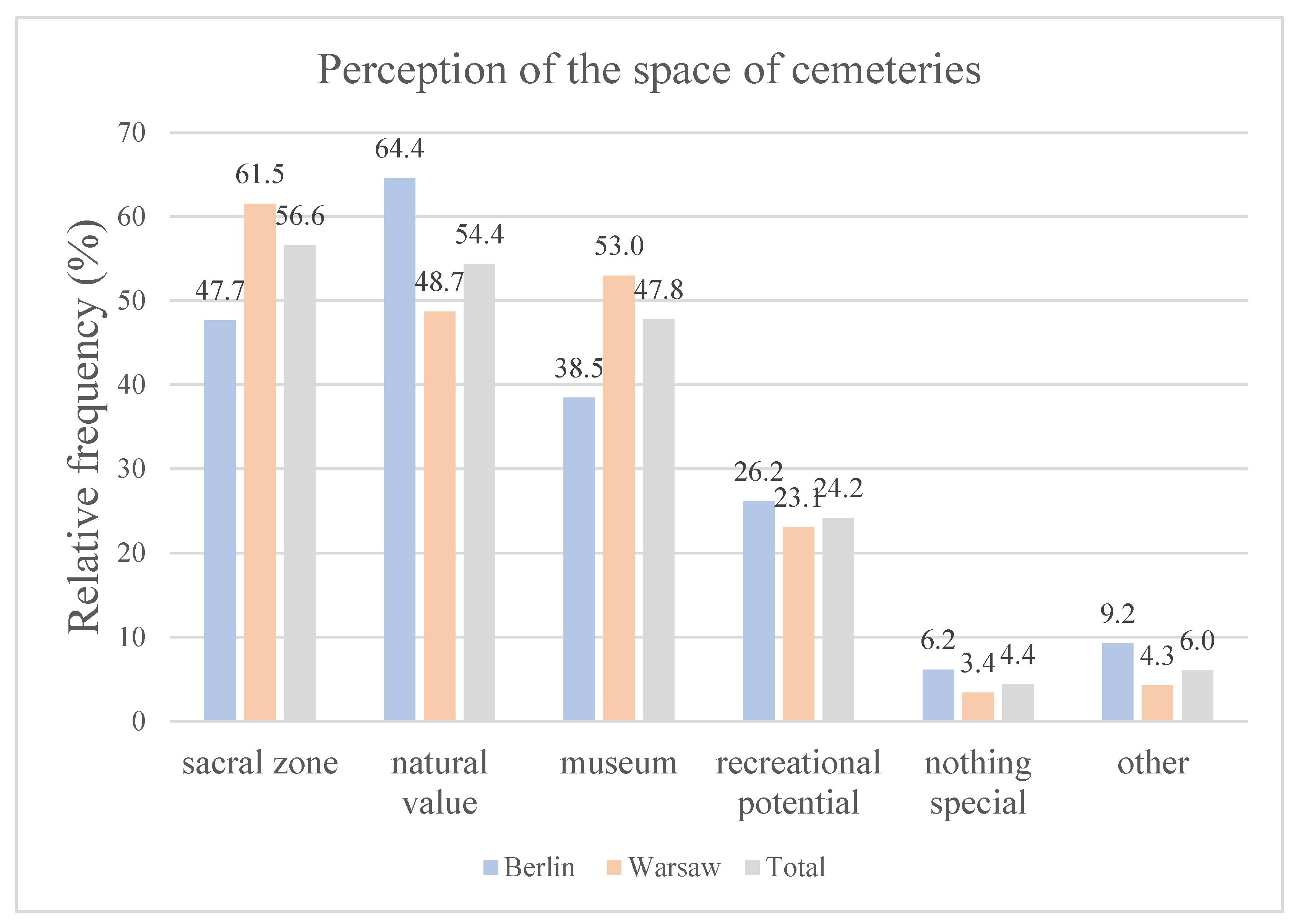

In a questionnaire survey, the young generation of inhabitants of both cities were asked whether they consider the space of cemeteries to be an important element of cities. In this case, regardless of whether the respondents lived in Berlin or Warsaw, they most often pointed out that cemeteries are important parts of cities (

Table 2). The chi-square test showed no significant differences between the answers given by the respondents from both cities.

Secondly, the respondents were asked how they perceived the space of cemeteries. For this question, they had the opportunity to select several answers and, if not, they considered the most appropriate indication. The average number of respondents to the survey was 1.9, and this number applies to both Berlin and Warsaw residents. The results of specific response rates are presented in

Figure 4. More often than Warsaw respondents, Berliners notice the natural nature of cemeteries, commenting on the possibility of observing different species of animals and plants, as well as on the fact that cemeteries are a kind of green island in the densely built-up area of cities, which is the statistically significant difference (

p = 0.039; X

2 = 4.257; df = 1). A significant difference, although statistically insignificant (

p = 0.0709; X

2 = 3.261; df = 1), was observed when cemeteries are perceived as sacred zones, which is observed more often by the inhabitants of Warsaw. Similarly, the inhabitants of Warsaw perceive cemeteries as a kind of museum. In this case, the difference is also not statistically significant (

p = 0.060; X

2 = 3.535; df = 1). Whether cemeteries are perceived as sacred zones or museums, the results obtained may not reflect the actual state of affairs, which is related to the difference in the number of answers given to this question (Warsaw

n = 117 vs. Berlin

n = 65).

Moreover, we asked respondents about the frequency of visits to the cemetery(s) in the last 12 months. The results are summarized in

Table 3. The data compiled in this table shows that in comparison to the inhabitants of Berlin who go to cemeteries most often, the inhabitants of Warsaw go to the cemetery at least twice a year (21.6% vs. 59.8%). This state of affairs may be due to the tradition associated with visiting the graves of dead relatives and friends during the feast of the dead and around Christmas. This may be reflected in the time spent on a visit to cemeteries, which in both cities is usually between 15 and 30 min. However, in the group of Poles, just over 11% of them spend more than 30 min on a visit to the cemetery. This may involve attending services held during the funeral or feast of All Saints Day in Polish cemeteries. If we look at the answers given by respondents to questions about whether they pay attention to the nature (flowers, birds, and animals) of cemeteries, it turns out that residents of both cities pay similar attention to them (

p = 0.094; X

2 = 6.381; df = 4). In the comments, the respondents most often mentioned trees, especially those of monumental or symbolic significance, e.g., weeping willows (

Salix babylonica) or tujas (

Thuja sp.), slightly less often indicated the possibility of observing animals, but most often pointed to the possibility of observing birds that nest in the crowns of trees growing in cemeteries. However, a statistically significant difference was observed for funeral objects such as monuments, crypts, or tombstones (

p = 0.011; X

2 = 13.005; df = 4). This state of affairs may be due to the character of the Warsaw cemeteries (like Powązki cemetery, selected often by respondents), where the most distinguished personalities of world culture and politics were buried. It is worth noting that their burials were usually crowned with monumental monuments, which even now, when their descendants are dead, are under the care of the conservatory of monuments and foundations, whose aim is to restore and protect such objects. This may also be due to the fact that the people of Warsaw are very strongly connected with the issues before the feast of the dead, during which visitors to the cemeteries throw in donations for the renovation of historic, unpaid, and neglected monuments of particular historical and cultural value.

Figure 4.

Perception of the cemetery space in Berlin and Warsaw residents’ opinions. Authors’ own elaboration based on the database [

38].

Figure 4.

Perception of the cemetery space in Berlin and Warsaw residents’ opinions. Authors’ own elaboration based on the database [

38].

Table 3.

Frequency of visits to cemeteries in the last 12 months and time spent on them, together with the degree of attention paid to nature and funeral facilities [

38].

Table 3.

Frequency of visits to cemeteries in the last 12 months and time spent on them, together with the degree of attention paid to nature and funeral facilities [

38].

| | How Often Have You Been in a Cemetery in the Last 12 Months? |

|---|

| | Daily | One to Several per Week | Monthly | Few Times per Year | One or Two per Year | Never |

|---|

| Berlin (n = 74) | 11 [14.9%] | 10 [13.5%] | 10 [13.5%] | 19 [25.7%] | 16 [21.6%] | 8 [10.8%] |

| Warsaw (n = 117) | 0 [0.0%] | 4 [3.4%] | 22 [18.8%] | 19 [16.2%] | 70 [59.8%] | 2 [1.8%] |

| Total (n = 191) | 11 [5.8%] | 14 [7.3%] | 32 [16.7%] | 38 [19.9%] | 86 [45.1%] | 10 [5.2%] |

| Berlin vs. Warsaw chi-square test | p = 0.000; X2 = 50.612; df = 5 |

| | How Much Time Did You Spend on Average Visiting the Cemetery? |

| <15 min | 15–30 min | 30–60 min | <60 min |

| Berlin (n = 64) | 7 [10.9%] | 37 [57.9%] | 20 [31.2%] | 0 [0.0%] |

| Warsaw (n = 111) | 6 [5.4%] | 58 [52.3%] | 39 [35.1%] | 8 [%7.2] |

| Total (n = 175) | 13 [7.4%] | 95 [54.3%] | 59 [33.7%] | 8 [4.6%] |

| Berlin vs. Warsaw chi-square test | p = 0.082; X2 = 6.698; df = 3 |

| | During Your Visit to the Cemetery, Do You Pay Attention to the Nature (e.g., Trees, Plants, Animals) of the Cemetery? |

| Not at All | Only a Little | To Some Extent | Rather Much | Very Much |

| Berlin (n = 64) | 0 [0.0%] | 8 [12.5%] | 5 [7.8%] | 25 [39.1%] | 26 [40.6%] |

| Warsaw (n = 116) | 0 [0.0%] | 4 [3.4%] | 8 [6.9%] | 43 [37.1%] | 61 [52.6%] |

| Total (n = 180) | 0 [0.0%] | 12 [6.7%] | 13 [7.2%] | 68 [37.8%] | 87 [48.3%] |

| Berlin vs. Warsaw chi-square test | p = 0.094; X2 = 6.381; df = 4 |

| | During Your Visit to the Cemetery, Do You Pay Attention to the Presence of Funeral Objects? (e.g., Historical Tombstones, Chapels, etc.) |

| Not at All | Only a Little | To some Extent | Rather Much | Very Much |

| Berlin (n = 64) | 2 [3.1%] | 8 [12.5%] | 15 [23.4%] | 22 [34.4%] | 17 [26,6%] |

| Warsaw (n = 117) | 2 [1.7%] | 3 [2.6%] | 17 [14.6%] | 41 [35,0%] | 54 [46.1%] |

| Total (n = 181) | 4 [2.2%] | 11 [6.1%] | 32 [17.7%] | 63 [34.8%] | 71 [39.2%] |

| Berlin vs. Warsaw chi-square test | p = 0.011; X2 = 13.005; df = 4 |

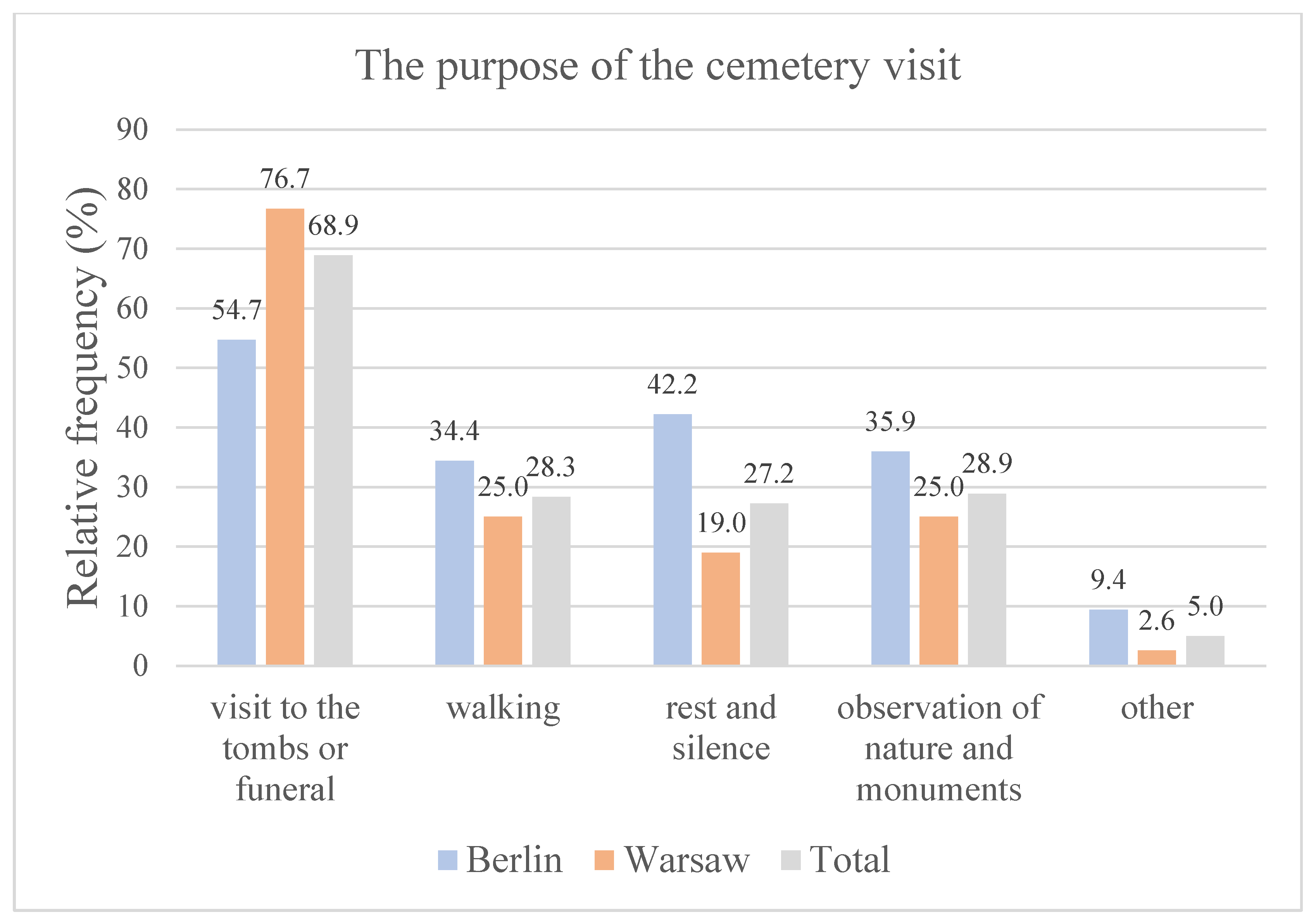

The respondents were also asked about the purpose of their visits to the cemetery. The visitors could choose several options from the given answers and also type their own answer. The frequency of responses to this question is shown in

Figure 5. A total of 180 respondents answered this question, who indicated 286 answers. The average number of answers was 1.6 answers per respondent, including respondents who most often chose one answer (one answer was selected 120 times). In the case of the studied group from Warsaw, the goal of visiting the cemetery was definitely more often visits to the graves of deceased relatives and friends, and this difference was statistically significant (

p = 0.001; X

2 = 10.192; df = 1). Berliners statistically significantly more often looked for places of rest and silence in cemeteries (

p = 0.001; X

2= 11,226; df = 1). Berliners went to the cemetery to walk and observe nature more often than Warsaw respondents, but this difference was not statistically significant (respectively,

p = 0.181; X

2 = 1.782; df = 1 and

p = 0.121; X

2 = 2.4026; df = 1). Similarly, Berliners more often pointed to a different purpose of visiting the cemetery than Warsaw inhabitants. However, in the case of residents of both cities, they indicated that they were passing through the cemetery because passing through the cemetery is a kind of shortcut.

The respondents were also asked if they saw the possibility of using historical cemeteries as potential recreation sites and what forms of recreation could take place there. The results of this part of the study are presented in

Table 4, where 28.2% of the inhabitants of Berlin and 36.8% of the inhabitants of Warsaw believe that cemeteries should not be places of recreation. This answer is observed most often by people who see the cemetery as a sacred zone, and they visit the graves of the dead as the purpose of their visits to the cemetery. On the other hand, almost 47% of Berlin residents believe that cemeteries should be places of recreation. In the case of Warsaw residents, it is less than 40%, with the vast majority of this group choosing the answer “very much”. About 1/4 of the inhabitants of both cities believe that cemeteries could be places of recreation to “some extent”. The chi-square test showed that the described differences are statistically significant.

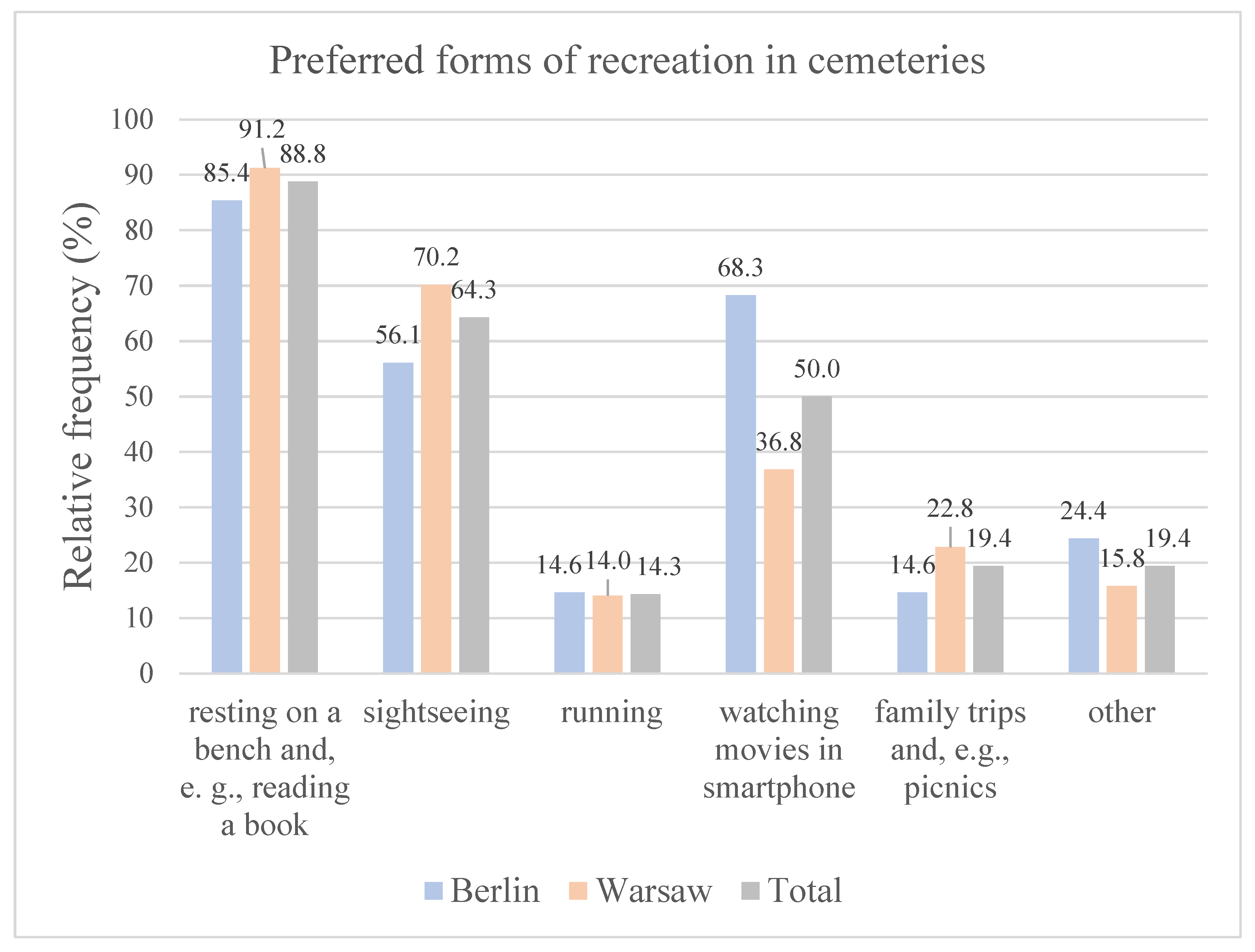

Those respondents who indicated that cemeteries could be recreational places (including the answer “to some extent”) were asked to state in their opinion the acceptable forms of recreation in cemeteries. For this question, the respondents could indicate several possibilities. A total of 98 respondents answered this question (41 residents of Berlin and 57 residents of Warsaw); they gave a total of 247 answers, most often choosing two forms of activity/recreation. The results of the estimation of the frequency of indications of selected forms of recreation are presented in

Figure 6. The most popular form of recreation indicated by the respondents, regardless of where they lived, was resting on a bench and, e.g., reading books. Slightly less often, they pointed out that the acceptable form of recreation in the cemeteries was sightseeing, although this form of activity was more often tolerated by the inhabitants of Warsaw. Respondents from Berlin were more likely to choose watching movies as an acceptable form of recreation, and this was the only statistically significant difference (

p = 0.002; X

2 = 9.43; df = 1). With similar frequency, respondents from both countries indicated that other forms of recreation are possible in cemeteries, and most often they indicated walking (47.4%), observing nature and/or funeral architecture (21.0%), contemplation (21.0%), and drawing and/or painting (10.5%). Of these activities, the smallest number of respondents prefer also jogging in cemeteries (slightly over 14% regardless of the place where they live).

The visitors were also asked whether cemeteries should be, in their opinion, included in urban green areas. The results are summarized in

Table 5. In this case, a statistically significant difference was observed between the answers given by the inhabitants of Berlin and Warsaw. This is because Berliners have a stronger view on including cemeteries in green areas (nearly 48% of them think they should definitely be part of the urban green areas). Nevertheless, both respondents from Berlin and Warsaw agree that they should be part of urban greenery (respectively, 65.7% and 69.0% of respondents) and point out its relevance to cope with the effects of climate change (greening cities, biologically active surface increase, adaptation of degraded areas to new natural and recreational function, etc.).

4. Discussion

Our observation and pilot study of questionnaire survey show that cemeteries in Germany and Poland differ in the level of maintenance of these sites and the way they are used [

38]. German cemeteries are well landscaped with vegetation, especially shrubbery and ground cover, while Polish cemeteries are “deserts” that are hard to call green spaces. The trees there are stunted, and the old trees need to be replaced with new species that are more resistant to harsh climatic conditions. However, cemetery managers decide to use these places for new graves, which makes the cemetery a mix of concrete and granite at a higher temperature compared to the surrounding green areas of the described cities [

10,

11,

29,

40].

Although both cities are represented by multi-confessional cemeteries, the land use between the Polish and German cemeteries is different. In Germany, cemeteries were partially designed as parks, not just places of burial [

41]. In contrast, Polish cemeteries are a sphere of the sacred, which according to our research, the cultural beliefs of the people do not allow for all recreational forms. This stems from religion and the belief of Poles in the “sanctity” of cemeteries and burials, where respect must be shown [

1,

11]. Thus, recreation is not well accepted there. However, we observe that the younger generation is more secular and allows recreational activities. For example, in municipal cemeteries, there are free spaces that could be used for summer cinemas or reading books near planned cafes or benches in the future. This trend is also visible in the latest sociological research from 2025 on religious beliefs by the youngest generation in Europe, especially including Poland [

42]. These studies show that the young Polish generation is one of the fastest societies moving away from Catholicism in Europe in recent years. This is also a potential of these places that should be utilized in the future, as Polish cities like Warsaw or Łódź (as we researched earlier) need more recreational spaces, especially those that are peaceful and free from commotion, due to the concrete city and population density [

36,

43].

However, the spatial layout of cemeteries in both countries is mainly determined by urban area density, the city’s historical context, their earlier/common function (ecosystem services), and the neighborhood. According to the literature query for German cemeteries, the arrangement of paths, vegetation, and graves is mostly part of planning by urban ecologists, landscape architects, or horticulturalists [

30,

36,

41,

45]. In contrast, in Poland, the burial area is determined by managers (church administration or religion groups stakeholders); rarely are they part of common landscape planning for social and future needs, except for two selected examples of Warsaw city (Cmentarz Północny, Cmentarz Południowy) designed basically as big-scale open burial spaces with decorative vegetation and meadows [

43,

44,

45]. Furthermore, their land use of common urban cemeteries is mostly represented by arranging new graves due to new burials and cutting down the vegetation, including old trees with historical meaning or layout (lime or spruce tree avenues) that we also observed as negative feedback in open comments from the questionnaire survey [

38].

4.1. Pro-Ecological Cemeteries Trend for the Sake of Europe’s Climate and Landscape

Concerns about the effects of climate change transcend political divisions—nearly 70% of Poles and Germans want the government to spend more on protecting the country from increasingly violent weather phenomena. According to the latest research, the government should do more to protect citizens from the effects of El Niño and La Niña climate change. As shown by current research conducted by the IPSOS (fr. Institut Public de Sondage d’Opinion Secteur) and UFZ (Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research) agencies, the majority of urban residents in Poland and Germany agree that climate threats are among the greatest contemporary challenges and require the most urgent national action [

47].

For example, more than half of the respondents associate last year’s flood in Lower Silesia, as well as the same number of Germans in the Ruhr Valley and Munich, with long-term negligence in climate policy and water management. Subsequently, 57% of Poles and Germans believe that the drought problem in Europe is directly related to climate change and requires urgent solutions. Meanwhile, 55% of respondents believe that just as we are moving towards 5% of GDP expenditure on defense, we should guarantee at least 1% of GDP for national climate security [

48].

Given these data, we believe it is necessary to amend the Act on Environmental Protection [

41], which will enable the effective implementation of the right to a safe climate and build real resilience of Poland to the effects of the climate crisis, just as it has been the case in Germany since 2024. Among the key demands are a minimum annual public spending threshold for improving Poland’s climate security, amounting to at least 1% of the country’s GDP. We also believe that there should be a requirement for adaptation plans for green infrastructure, including cemeteries, not just at the local level but also at the regional and national levels [

49].

The need to improve climate security is also emphasized by the authors of a recently published report, so-called “Costs of climate change in Poland” (pl. “Koszty zmiany klimatu w Polsce”) [

50]. The ClientEarth Analysis shows that Poland in 2025 may lose up to PLN 124 billion annually as a result of climate change. On the one hand, without acceleration of transformation and adaptation measures, the losses will be increasingly greater. Not only the state budget but also society will suffer, paying with their property, health, and in extreme cases—even their lives. On the other hand, potentially, they can support these activities by utilizing neglected green areas such as cemeteries.

Previously underestimated but climatically important green spaces, such as unused active biological surfaces, should be passive recreational areas accompanying active recreation. Therefore, they should be included as an important element of the green infrastructure of cities. In Germany, these parks are museums rich in plants such as trees planted in alleys, ornamental shrubs, and ground cover plants [

51,

52]. In Poland, plants are removed to make way for new graves and to ensure user safety. Old trees are cut down, but no new ones are planted in their place. There are no standards that would minimize this phenomenon because protection plans and development directions contained in documents and planning studies lose their legal force with the amendment of documents, or the entry into force of new law, and/or their disorganization from general to specific. Therefore, we should look at the designs of German cemeteries as exemplary solutions that can also serve as recreational parks. The respondents in our studies pointed out these aspects. Cemeteries can be an alternative form of recreation, especially for neglected or peace-seeking people, which can distinguish them from other green areas with a wide range of recreational and sports activities.

Additionally, solutions based on the construction of sustainable building materials, such as permeable surfaces, benches, waste-sorting bins, or fences and enclosures made from local raw materials or recycled materials, should be introduced. It is worth introducing a rich collection of plants, including hedges and shrubs, to separate graves in the cemetery space. Collecting rainwater, building retention tanks, and rain gardens can mitigate periodic water shortages.

In turn, the water collected from heavy and unannounced rainfall during the summer and fall periods can be used to water plants at the cemetery and to supply toilets in the event of a long drought or lack of drinking water.

4.2. Looking at New Trends and the Environmental Pollution Phenomenon

In Poland, as opposed to Germany, the tradition of visiting the cemeteries stems from tradition and adherence to customs during the holidays. This trend is proven by the results of surveys conducted among the young generation of our studies for Berlin and Warsaw. It is worth noting here that All Saints Day is strongly rooted in Polish culture and tradition, together with a deeper reflection on the dead and passing away. Thus, this trend is also mostly visible in Polish cemeteries. However, according to the cultural background, this reflection is increasingly being “environmentally polluted” by other, shallower forms of celebration in cemeteries. One of them is the so-called Grobing [

53]. The term Grobing is colloquially called, generally with disapproval, the phenomenon of visiting cemeteries in All Saints by people who treat it as entertainment and an opportunity to present themselves in fashionable attire [

54]. People in creation sometimes treat this like a lavish holiday, just going to the cemetery to show themselves to others, going for a walk between the graves, and taking a selfie at the grave for everyone on social media. This, in short, is the cemetery lance. All Saints Day is in this way the best opportunity to gaze on the cemetery fashion and track down the radical cemetery women in the crowd. This entire tradition is not ecological and is rather associated with the production of large amounts of artificial waste and the problem of waste management, which is a significant problem of sustainable development [

55]. On the other hand, we do not encounter such a phenomenon in Germany, which is due to the fact of secularization and multiculturality of the German society, and consequently, the non-attachment of society only to Catholic holidays, as is the case in Poland. In Germany, we have a trend of using LED lights (replacing batteries) and planting plants on graves that can be cared for throughout the year by pruning and watering, which is also mentioned by the Germans surveyed during our survey. The tradition has its roots in gardening and tending to one’s own home garden.

It is worth emphasizing that environmental protection of the cemetery against littering may weaken the La Niña and El Niño phenomena. This should be performed because climate change effects are already dangerous and have serious consequences, and temperature fluctuations, as well as changes in high and low pressure, even during the warm summer. Climate change phenomenon in question is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is characterized by alternating El Niño and La Niña phases, influencing rainfall and drought patterns.

4.3. Sustainability of Cemeteries

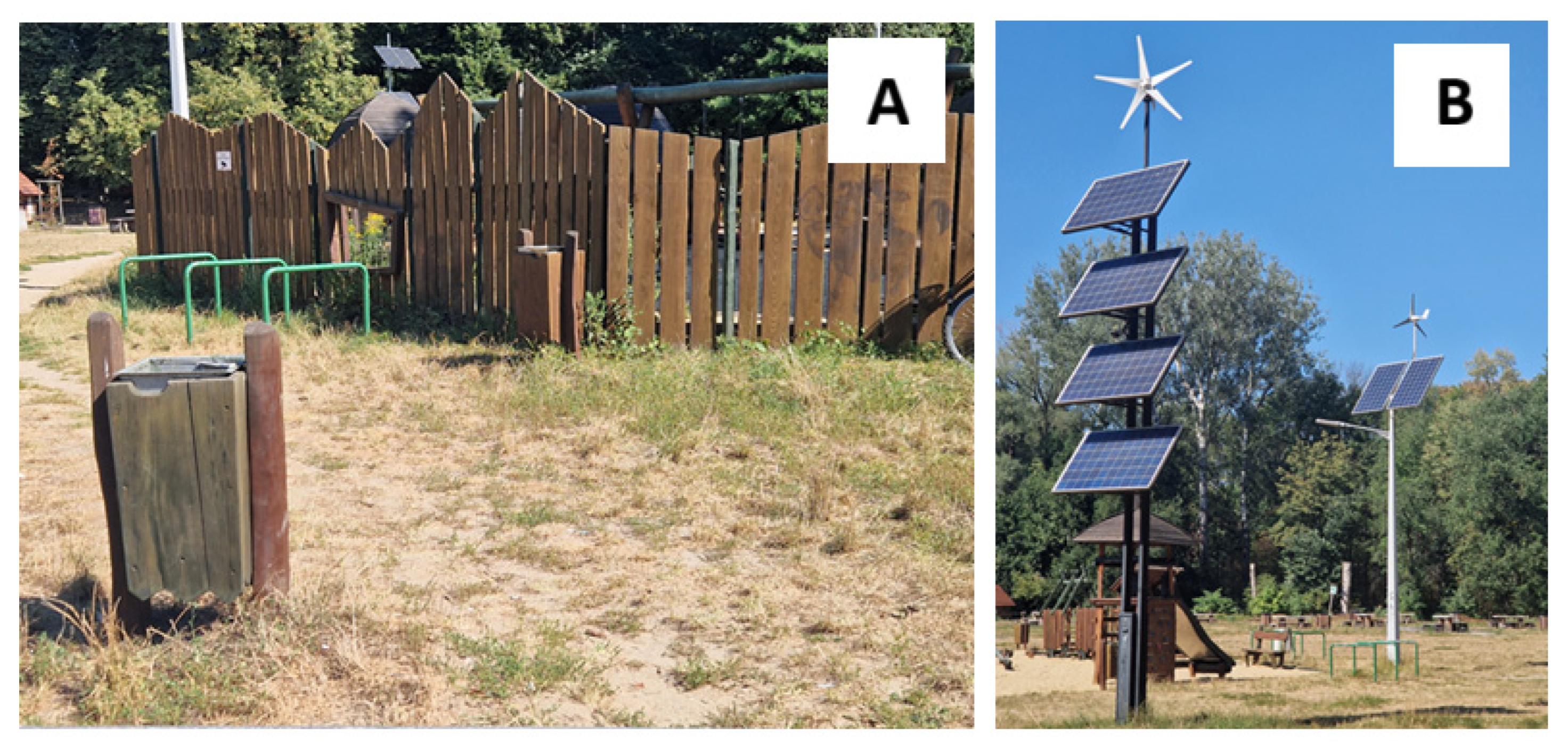

During the conducted research, we noticed that cemetery equipment, i.e., materials used to build cemetery surfaces, is not very ecological and should be changed in response to climate change. We suggest using recycled materials, such as upcycled or recycled materials, for example, used for benches, trash cans, railings, and pavement. In densely built-up areas in city centers, it is suggested that eco-friendly materials such as permeable surfaces made of aggregate and stone be used instead of hardened surfaces (mainly in the side alleys of the cemetery with low traffic), as well as local materials (such as spruce or beech wood) from nearby urban forests obtained through forest management (

Figure 7A). This way, the temperature of cemeteries can be lowered by even 4 degrees Celsius, as proven by research conducted in other urban green areas [

56,

57]. Using water-permeable surfaces can improve the area’s water retention and gradual infiltration of water into plant roots, reducing rapid water runoff into storm drains. Large areas of high-quality green spaces, parks, and old cemeteries also limit the effect of the so-called “urban heat island,” which can be particularly troublesome during summer heat waves.

Considering all the non-aesthetic functions that urban greenery can perform (oxygen production, air purification from pollutants, facilitating water retention, improving the microclimate by humidifying the air, bacteriostatic action, and reducing the heating of the ground and buildings), it is now referred to as the UGI, because just like technical infrastructure, it plays a very important role in improving the quality of life in the city. Greenery, especially tall and covering large areas, including cemeteries, is a kind of universal infrastructure (like no other built by man) replacing or supplementing expensive stormwater drainage [

56]. Due to the multiplicity of functions, the monetary valuation of social benefits resulting from maintaining green spaces is difficult and complicated, but such attempts are being made [

57]. It is worth noting that one mature deciduous tree (100-year-old oak) provides 3500 kg of oxygen annually to meet the oxygen needs of 10 people. Assuming that there are 100 mature deciduous trees on each cemetery plot, each plot can meet the oxygen needs of 1000 people. This issue may be part of future research on cemeteries in urban European areas due to rapidly visible climate change and no water in the soil [

58].

It should be emphasized that especially valuable and useful for the urban community are the mature and ancient trees that still grow on the old city cemeteries of Warsaw and Berlin. Unfortunately, planting new, young trees does not compensate for the benefits of cutting down old ones. Therefore, it is so important to care for the cemetery trees and limit their unjustified cutting down due to the pressure of space for new burials [

59].

However, we see that some plant species often observed in cemeteries, especially the small-leaved linden and the silver fir and bird cherry, are beginning to die off due to climate warming and lack of rain, and thus an increasingly long period of drought, especially in summer and autumn, when these seasons used to be more rainy. We suggest that these species be replaced with species that are resistant to difficult urban conditions (pollution), fast-growing, inexpensive to maintain, and resistant to pests and fungal diseases. These include Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), Japanese Spurge (Pachysandra terminalis), Sedum sp., field maple (Acer campestre), alpine currant (Ribes alpinum), common hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), Golden weeping willow (Salix sepulcralis), and poplars (Populus sp.) that can tolerate periodic water shortages.

However, due to the long-term effect of oxygen production from mature trees, the first priority should be to increase the share of ground cover and shrub vegetation, which will more quickly achieve the biomass needed for oxygen production. It is also suggested to introduce lighting that uses renewable energy sources (e.g., wind turbines or solar panels), which has been successfully implemented in Warsaw green spaces, for example, in playgrounds (

Figure 7B).

4.4. Cultural Values of Cemeteries

During the analysis of the conducted questionnaire survey about the importance of cemeteries among young people from Poland and Germany, one of the opinions was especially interesting in justifying the chosen research topic. “The cemeteries have a specific maintenance for me because they are burial sites, but I don’t think they concern me on a daily basis. I usually pass by their high walls, and I know that they are there, but I’m not really tempted to go there; I have more important things to do.” This approach shows that even though the urban cemeteries are, as one of our interviewees wrote, “Islands of green in a concrete city, really important because of climate change rapidly”, they still remain a zone excluded from use by the living. This approach seems to have its origin in the Christian culture, where the cemetery is the zone of the dead, the zone against which the living were warned by the lanterns of the dead and protected by high walls. On the other hand, we see that urban cemeteries are points of excursion (e.g., Père-Lachaise) and care for the preservation of historic funeral objects, which is important for the formation of identity and natural biodiversity function [

59]. Moreover, the old buildings and graves, as well as old trees (avenues) of historic cemeteries, provide a microclimate, which seems to be important in the issue of urban climate change and cooling in summer seasons and heat islands. This issue built positively the network of urban green infrastructure (UGI), taking into account the fact that urban cemeteries are located in the vicinity of housing estates and on the outskirts of cities (Warsaw and Berlin), and they constitute seals connecting green areas and other undeveloped areas significantly covered with vegetation [

1,

2,

60,

61,

62,

63].

In Germany, cemeteries are treated as green public spaces. An additional advantage of these places in Berlin is the well-kept and biodiverse greenery, which provides good conditions for walks and thus more frequent visits to the graves of not only those close to the respondents [

50,

51]. Regardless of the place of living and nation, the respondents consider cemeteries to be an important element of the structure of cities. In our research, we observe that Berliners more often than Warsaw residents notice the natural value of these areas, which may be due to the greater care of the Germans for greenery and a higher degree of care for its condition, also due to the horticulture tradition observed strongly in the extra question form in the questionnaire survey asking about having flowers in gardens by respondents. This may be due to the fact that cemeteries are treated as memorial parks where you can go for a walk and admire nature, whereas in Poland, such an approach is far from the everyday reasoning of the younger generation. Young people in Poland occasionally treat cemeteries as a kind of museum with historical tombstones, but this applies mainly to historic cemeteries, such as Powązki Old Cemetery in Warsaw. This idea is closer to the idea of thanatotourism [

2], i.e., visiting and learning about the history of the city through a visit to the cemetery. This idea may find new applications in the developing world, which is focused on sustainable development and promoting an eco-friendly lifestyle. Promotion can be achieved by visiting with QR codes (lighting candles with a smartphone, information about the history of the place, and the deceased), which can reduce the amount of garbage on the cemetery grounds and promote healthy passive recreation. The beginnings of such thinking could be observed during the pandemic when visits to the cemetery were limited, which was also mentioned by our respondents.

4.5. Cemeteries as Sacred and/or Rest Zones

It is worth noting that Poles, as a Catholic country (despite the progressive secularization of the younger generation), perceive cemeteries as a sacred zone. This is due to the result of centuries-old tradition connected with the perception of cemeteries as zones only for the dead. For them, the cemeteries are places of reflection, preference, and sadness, and places where there are graves of the dead which need to be shown respect. Furthermore, the cemeteries for Poles are treated as a kind of museum (of sacred art), which may also result from the increasingly common trend connected with eco-friendly thanatotourism. Poles are also brought up in connection with tradition, which includes elements such as the feast of the dead and the annual events connected with it [

2,

8,

11,

14,

16]. The purpose of these collections is to save ruined and dilapidated funeral art monuments, for which there is usually a lack of funds from state institutions.

Finally, our surveys among young people also show that if the cemetery is treated as “a sad place”, there is no reason to visit it more often than necessary. Poles definitely choose a cemetery less often as a resting place. They visit cemeteries just when it is appropriate. Therefore, more often than in Germany, Poles do not allow these places to be used as recreational areas. There is only one reason that Polish respondents already allow some form of rest in cemeteries, which is mainly sitting on benches, sightseeing (together with contemplation of the dead people), that also most distinguishes them from the German group of young generation at all.

5. Conclusions

The selected multi-confessional old cemeteries in Warsaw and Berlin to enrich our knowledge on various functions (ecosystem services); thus, comparative data analysis enables drawing final conclusions concerning the value of methods verified in this project and the current ecological and recreational potential of cemeteries. Disseminating the newly acquired knowledge raises public awareness on the ecological role of studied cemeteries and encourages good practice in cemetery management by urban citizens.

The survey allowed us to answer the following questions: whether historical cemeteries are an important element of urban space for city dwellers, what is the purpose of visiting the cemetery, do the respondents observe nature or funeral objects mostly, and whether they see the possibility of using the cemetery area as a potential place for recreation or rather only identify this place as a sacred zone. The results showed differences in the responses of the Polish and German generations of young people, which is due to the traditional and cultural differences in both research groups.

Regardless of their place of residence, the young generation of respondents considers urban cemeteries as an important element of the structure of Central Europe’s capitals (Warsaw and Berlin).

Germans more often than Poles notice the natural value, as well as spend free time in cemeteries. This is due to the greater care of greenery by Germans and the lack of other grassland areas with well-preserved biodiversity in the neighborhood.

Poles, as a Catholic country, in spite of the progressive secularization of the younger generation, perceive cemeteries as a sacred zone that comes from Polish tradition. This phenomenon distinguishes them from multicultural and secular Germans. Nevertheless, if Poles are already going to the cemetery (due to tradition and the environmental burying phenomenon), they visit cemeteries much less often than Germans (due to identification of cemeteries as public green space similar to urban park areas in the city).

The research can find its application in public opinion surveys of a narrow group of environmentally important green areas, such as city cemeteries, which are often underestimated or overlooked in urban survey research (especially in Poland).

Following the example of German cities, due to moving away from religious beliefs of younger generations, greater attention should be paid to the recreational aspect of Polish cemeteries. This is justified in the context of climate change and the use of unused space in sacred places.

The significant yet underappreciated role of cemeteries as “green islands” in mitigating the effects of climate change should be recognized, mainly due to the presence of old trees that meet the oxygen needs of society.

The proper selection of sustainable materials and plants for cemetery modernization in the face of climate change must become a challenge for the future. This goal will allow for a better understanding of cemeteries’ potential as an important but poorly recognized or undiscovered element of urban green infrastructure.

The paper can set guidelines for cemetery managers and local authorities on how to manage these spaces and adapt them to the needs of the younger generation of the Polish–German population and climate change for an environmentally friendly society.

Future studies of urban cemeteries should pay closer attention to research conducted among the younger generation, who will shape the future directions of urban development, including influencing the functioning of urban green areas as an important element of sustainable environmental urban structure.

In future research on cemeteries perception by inhabitants, we suggest also to add selected groups of respondents from other European cities as well as to expand the survey to include new, not yet analyzed threads that appear in the open suggestions of young respondents (grobing environmental phenomenon, cemeteries biodiversity, cemeteries equipment as cafes, buildings, or other preferred facilities appropriate for reading books or displaying movies on cemeteries as important elements for the respondents to spend time in those specific areas of greenery in cites, and El Niño/La Niña climate change, etc.), which should be the subject of further research in this field.

The idea should be incorporated of cultural cemeteries as an essential element of urban green infrastructure by developing them for recreational purposes and implementing proper waste management focused on biodegradable materials or using eco-friendly materials by promoting pro-ecological trends as a model for the future in European cities.