1. Introduction

The transformation of rural environments into hybrid rural–urban spaces is becoming an increasingly relevant topic within contemporary urban and landscape studies, prompted by accelerating urbanization and the shifting patterns of lifestyles of urban-dwellers moving towards the countryside. Driven by global phenomena such as remote working, second-home ownership, and lifestyle migration, heritage homesteads in rural areas, including Lithuania, are evolving into multifaceted environments that integrate both traditional rural and contemporary urban lifestyles and management practices [

1]. These heritage sites, which are inherently linked with local landscapes, traditional construction, land management practices, and cultural histories, face challenges in adapting sustainably to modern needs without compromising their authenticity, landscape connections, and inherent sustainability rooted in ancestral knowledge and practices [

2,

3].

The development of rural–urban hybrid environments, even those with deep historical roots, has intensified notably in response to recent global disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which pushed urban residents to search for rural refuges that could serve simultaneously as workplaces, residences, and areas for recreation. This movement has revealed the complexities inherent in blending urban functionalities with rural landscapes and traditional lifestyles, creating environments characterized by multifunctionality and layered identities [

4,

5]. Despite this trend, the sustainable management and the subtle aesthetic expressions that accompany these rural hybrid spaces, particularly within the heritage context, remain insufficiently explored by researchers. Moreover, it is acknowledged that the formal correspondence with the principles of sustainability does not ensure the aesthetic quality of architecture and its aesthetic expression, and defining sustainability aesthetics is extremely difficult [

6]. The literature on environmental hybridization has primarily emphasized urban perspectives, while the nuanced transformations of rural contexts within these hybrid environments remain comparatively underexplored, and therefore demand greater attention from researchers [

4]. In response to these observed knowledge gaps, this research proposes two interconnected hypotheses:

- (1)

Sustainable management and aesthetic expressions in heritage homesteads in rural settings involve complex, subtle layers interconnected with tacit cultural meanings, forgotten historical practices, and informal knowledge, necessitating qualitative, in-depth investigations for their comprehensive understanding;

- (2)

Sustainability aesthetics in these settings is perceived incrementally, with not all aspects being immediately evident; thus, analyses should encompass both tangible elements and intangible, invisible dimensions, such as tacit knowledge and historical-cultural layers, for deeper understanding and effective implementation.

The primary aim of this research is to conduct a qualitative, in-depth exploration of a selected heritage homestead in the small Lithuanian town of Čekiškė. In this case, the homestead was deliberately acquired by its new owner as an experimental object to test how heritage could be actualized and sustainability aesthetics created. While the proposed future use emphasizes museum and educational functions, the interventions are transferable to residential settings and present relevant principles for contemporary rural newcomers. Moreover, many new residents in small Lithuanian towns and villages diversify their activities beyond agriculture into education, hospitality, and creative services, making such multifunctional adaptation strategies both realistic and necessary for local regeneration. This analysis will focus on examining the four distinguished developmental stages of the homestead through multiple complementary theoretical lenses, aiming to test the outlined hypotheses and to reveal the less visible, tacit dimensions involved in creating sustainable management strategies and their aesthetic expressions. This research aims to contribute to the understanding of how heritage homesteads can be sustainably adapted to contemporary needs without losing their cultural authenticity and ecological integrity.

The research methodology is qualitative, based on narrative, contextual, and historical analyses. Four complementary theoretical frameworks were applied for the analysis: (1) the cultural ecology model by J. Steward, which elucidates the reciprocal relationships between environment, subsistence practices, and cultural adaptations [

7]; (2) the perspectives of environmental ethics (egocentric, homocentric, biocentric, and ecocentric), which examine the evolving ethical human–environment relationships [

8,

9]; (3) the principles of biophilic design [

10], based on the biophilia hypothesis [

11], that consider the inherent human connections to nature within design and land management processes; (4) and the framework for ecological aesthetics by M. DeKay [

12], which structures aesthetic perception through progressive stages from visual to evolutionary. An integrated application of these approaches to the case study object is anticipated to yield insights into how tangible and intangible layers, ranging from explicit architectural practices to implicit cultural knowledge and forgotten traditions, influence sustainability aesthetics and management practices in the context of rural hybrid environments. Data collection includes qualitative in-depth on-site observations and documentation in photographs and drawings, and an analysis of the scientific literature, archival records, and historical photographs.

2. Theoretical Contextualization

Contemporary researchers increasingly recognize vernacular countryside heritage as a vital component of sustainable design. Such architecture aligns with local environments, cultural practices, and traditional materials, making it an “eloquent example of sustainable design” [

13]. Recent studies show that local ethnic building traditions embody biophilic and ecological principles [

13]. Likewise, researchers emphasize that evaluating vernacular dwellings requires a multi-dimensional perspective beyond narrow technical criteria. Samalavičius and Traškinaitė note that traditional rural buildings, whether Italian stone trulli or Lithuanian wooden farmhouses, accrued structural, aesthetic, and cultural qualities over centuries and can still serve diverse functions beyond mere tourist consumption [

14]. Such insights reveal the enduring wisdom and tacit knowledge embedded in vernacular architecture and its relevance for modern sustainability challenges and the aesthetic development of environments.

Within rural development discourse, the integration of cultural heritage with sustainability is increasingly emphasized. Studies stress that preserving traditional architecture can revitalize local economies when paired with sustainable tourism [

15]. International frameworks reflect this approach: UNESCO now recognizes “the transformative power of heritage values in rural areas” as a key enabler of sustainable development, advocating for the inclusion of culture in the 2030 Agenda [

15]. These trends illustrate a growing consensus that vernacular rural landscapes, including in European and post-socialist contexts, hold untapped potential for sustainable development if managed with a balance between conservation and adaptive reuse [

16].

Methodologically, this study builds on a well-established tradition of in-depth qualitative case studies in heritage and sustainability research. Proponents of this approach argue that single-case analyses yield rich insights that broad surveys often miss: a case study can have an intense focus on a single phenomenon within its real-life context, and it can include both a process of learning and the product of that learning [

17]. B. Flyvbjerg further dispels the notion that case studies lack scientific rigor, noting that “one can often generalize on the basis of a single case” and that such studies contribute to theory by the “force of example” even when formal generalization is limited [

18]. However, scholars also point out that certain regions remain under-researched. Vernacular architecture in post-Soviet Eastern Europe, for instance, has long been “neglected and marginalized in research” [

19], and the overall vernacular legacy of the former Soviet sphere remains “largely unscrutinized” in contemporary scholarship [

19]. By examining a Lithuanian rural homestead through multiple theoretical lenses, the present study addresses this gap. It situates itself at the intersection of such thematic strands as vernacular sustainability, rural heritage development, and qualitative case-study analysis in order to uncover latent sustainability frameworks and aesthetic values within vernacular heritage, thereby contributing to current debates and demonstrating the value of a deep, contextual approach.

Contemporary heritage homesteads in Lithuania occupy zones of tension between historical authenticity and evolving ecological–cultural identities. To assess their sustainable hybridization and to test the hypotheses raised above, this research integrates four complementary theoretical lenses—cultural ecology [

7], environmental ethics [

8], biophilic design [

10], and ecological aesthetics perception levels by M. DeKay [

12]. These four theoretical approaches were selected because they are mutually complementary and collectively encompass the main dimensions of sustainability: economic (subsistence and resource use), socio-cultural, and ecological. Each framework provides a lens through which processes, interventions, and their aesthetic outcomes can be traced, and together they allow for a holistic, qualitative exploration of the tacit layers of sustainability embedded in heritage homesteads. This section presents the description of all four selected theoretical approaches and their potential in the analysis of heritage homestead transformations as well as the joint methodological framework developed and applied in this research.

Cultural Ecology: Cultural Ecology, as theorized by J. Steward [

7], is a framework that analyzes how human cultures adapt functionally and materially to their environments. Central to this approach is the concept of the “cultural core”: the constellation of subsistence practices, technologies, and interactions with the environment that directly structure resultant cultural forms such as social organization, belief systems, etc., including aesthetic expression. The core encompasses environmental conditions, such as available resources, climate, and ecology; the technical means of utilizing them, including tools, labor, and knowledge; and the resultant social structures, forming concentric analytical layers from the ecological base to the cultural superstructure. The cultural ecology analytical sequence begins with documenting the physical and biological environment: resource availability, climatic constraints, and ecosystem dynamics. Further it analyzes the technological adaptations and subsistence strategies that communities employ: tools, agricultural systems, and material technologies. Finally, it traces how these adaptations give rise to social institutions, symbolic systems, spatial arrangements, and aesthetic forms. It is important to note that J. Steward [

7] advanced a multilinear evolution model, where similar environmental pressures may lead to multiple cultural expressions. In methodological terms, Cultural Ecology encourages a layered research design: reconstructing environmental substrata through archival, landscape and material study; documenting technological systems through ethnographic interviews, architectural surveys, and agro-ecological mapping; and interpreting aesthetic–cultural patterns via discourse, craft analysis, and heritage narratives.

When applied to the Lithuanian heritage homestead, the cultural ecology framework offers a structured means to reveal the tacit sustainability embedded in traditional rural lifeways. First, by reconstructing environmental and subsistence layers, it is possible to identify historically functional design elements that serve ecological ends. These features often contain informal knowledge and practices no longer explicated in contemporary discourse. Second, linking these ecological and technical elements to social–cultural expressions, symbolic garden layouts, artisanal craftsmanship, etc., reveals the cultural meanings encoded in vernacular aesthetics, thus revealing multi-layered cultural mediation. This form of inquiry directly addresses the first hypothesis: that sustainable management and aesthetic expression in heritage homesteads are woven into intricate, subtle strata of tacit cultural meanings and forgotten historical practices, only retrievable through qualitative, in-depth investigation. Moreover, the cultural ecology avoids simplistic environmental determinism by acknowledging historical agency. For instance, the same biophysical environment may produce distinct homestead typologies depending on shifting agricultural regimes, agricultural reforms, family structures, or external influences, mirroring the multilinear evolutionary model. This sensitivity enables comparative analysis across regions, revealing how micro-historical differences produce variant sustainability profiles.

Figure 1 presents a cultural ecology model and its potential for application in historical homestead transformation analysis.

Biophilic Design: Biophilic design is based on the biophilia hypothesis formulated by E. O. Wilson [

11], which posits that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other non-human living forms [

20]. In the context of heritage homesteads, where past inhabitants were unaware of formal design theories, biophilic design provides a lens through which to interpret unconscious, nature-integrative spatial and aesthetic forms that supported well-being and ecological harmony. In contemporary design, the 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design developed by Terrapin Bright Green identify empirically grounded strategies grouped into three categories: (1) nature in the space—the visual/non-visual sensory connection, dynamic light, and water presence; (2) natural analogues—biomorphic forms, material connection, and complexity/order; and (3) nature of the space—prospect, refuge, mystery, and risk/peril. These categories demonstrably enhance psychological, physiological, and cognitive design outcomes [

10].

Biophilia and the biophilic approach to design can be applied to analyze heritage homestead, both as a pattern-based analytical framework and as a narrative tool for interpreting homestead user experience. First of all, a pattern-based inventory using the 14 patterns [

10] can be carried out for the presence or absence of biophilic elements focusing on different stages of development of the homestead, based on archival plans, archaeological evidence, ethnography, observations, and other available data. Through this method, it is possible to assess whether the tacit design corresponds with biophilic principles, even if unconsciously realized. Beyond this checklist verification, qualitative data, including oral histories, diaries, and sensory descriptions, can be applied to reconstruct biophilic experiences embedded in everyday life. The identification of biophilic patterns, whether present or diminished, provides empirical evidence of historically sustainable spatial–aesthetic coherence; narrative interpretation links these patterns to experience and meaning, revealing how functional and sensorial design can bring about ecological attunement without explicit theoretical knowledge. Utilizing the biophilic design approach complements cultural ecology, which situates forms within subsistence systems, by emphasizing the experiential and affective dimensions of sustainability.

Environmental Ethics: Environmental ethics explores the evolving moral relationship between humans and the non-human world. According to the analyzed literature, it identifies four primary value orientations— egocentric, homocentric, biocentric, and ecocentric—which reflect progressively wider spheres of moral concern, from self-interest to holistic ecosystems [

8]. Egocentric ethics prioritize human utility, with nature regarded primarily as a resource for individual or human-group ends. This view often justifies exploitative land use, reducing environmental practice to anthropocentric cost–benefit calculations. Homocentric ethics extend moral value to broader human communities, families, and societies, but still largely subjugate non-human life to human ends. Biocentric ethics assert that all living organisms carry inherent moral worth. This approach values individual organisms irrespective of their utility to humans. Ecocentric ethics go further, affirming the intrinsic value of entire ecosystems, including the relationships, processes, and non-living elements that sustain life [

8,

9].

In the analysis of the historical development of a Lithuanian heritage homestead, applying these ethical frameworks serves two key analytical functions: the temporal mapping of moral orientation and interrogation of tacit dimensions. For example, archival records, diaries, oral histories, and landscape features can reveal shifts in ethical orientation, for example, from egocentric exploitation in early modernization phases to more biocentric or ecocentric sensibilities in later conservation stages. Moreover, an analysis using environmental ethics value orientations might reveal invisible attitudinal strata behind physical forms: by classifying observed motif and management practices within these ethical categories, it is possible to reconstruct the moral compass guiding tacit design and care.

Environmental ethics complements biophilic design and cultural ecology approaches in this research by suggesting a way in which design features may be read as ethical statements, among other possible interpretations, thus helping to highlight moral dimensions often overlooked in hybrid transformations. Ultimately, tracking ethical orientation provides a compass for future interventions, ensuring that heritage homesteads evolve not only functionally and aesthetically, but also in alignment with deeper, increasingly regenerative moral commitments.

Ecological Aesthetics: Ecological aesthetics, as developed by M. DeKay [

12], presents a multi-tiered theoretical framework for understanding how aesthetic responses to environments, including the focus of this study, historical homesteads, deepen gradually, from mere visual aspects to the perception and appreciation of less visible ecological evolutionary processes. This layered perception model is particularly valuable for analyzing heritage homesteads, where sustainability aesthetics expressions are not instantly visible but emerge through nuanced engagement across historical phases and ecological complexity.

M. DeKay [

12,

21] distinguishes five connected and deepening levels of aesthetic perception, including visual aesthetics, phenomenological aesthetics, process aesthetics, ecological aesthetics, and evolutionary aesthetics (

Figure 2). The first immediate level of perception—visual aesthetics—focuses on form, color, symmetry, visual order and other visual features—the immediate, objective appearance of structures or landscapes. Phenomenological aesthetics further encompasses embodied, multisensory experiences, including textures, acoustics, thermal comfort, and the experiential qualities of movement through space. Process aesthetics recognizes dynamic patterns and underlying processes. According to M. DeKay [

12,

21], a design becomes aesthetic when it reveals cycles, flows, ecological relationships, and processes within its context. The fourth perception level—ecological aesthetics—reflects appreciation for designs that promote ecological health, demonstrating resilience, biodiversity, and alignment with natural systems. The fifth level of ecological aesthetics perception—evolutionary aesthetics—encompasses awareness of temporality and transformation: beauty perceived through change, adaptation, and increasing complexity across ecological and cultural timelines [

12].

Applying this model to a Lithuanian heritage homestead, each distinguished stage of homestead development can be analyzed through these five perceptual lenses (

Figure 2). By tracing which perceptual levels are deeply engaged or overlooked in different homestead development phases, it is possible to test the hypothesis that sustainability aesthetics emerge incrementally, with some levels only realized through deeper historical or experiential analysis. These deeper layers require qualitative, in-depth investigations, reaffirming the value of tacit cultural knowledge and site-based experience in revealing latent sustainable aesthetics.

Ecological aesthetics perception levels enrich the theoretical framework of the study as this model complements the biophilic design approach by revealing how sensory and experiential engagements point beyond mere a connection with nature, to system-awareness. It also complements environmental ethics by indicating whether aesthetic appreciation aligns with deeper ecological values, and cultural ecology, by locating aesthetic evolution within subsistence-driven spatial adaptations.

Theoretical Framework: Together, these frameworks enable a multi-scalar analysis, spanning form, experience, process, ecological health, and historical evolution, emphasizing that sustainable aesthetic coherence emerges not instantaneously but through layered perceptual, moral, and cultural journeys. For heritage homestead analysis and contemporary adaptations, this approach ensures that transformation strategies are not only functionally and visually sound but also ecologically resonant and historically coherent, anchored in the perceptual richness of place, time, and human–nature co-evolution.

Figure 3 presents the integrated methodological framework developed and applied in the course of this research. In this framework, the cultural ecology approach provides the diachronic foundation by tracing how subsistence modes and environmental constraints historically shaped homestead design and material culture; it uncovers tacit sustainable practices now possibly obscured by modernization. Cultural ecology multilinear evolution model emphasizes that cultural forms arise in adaptation to ecological contexts [

22]. Within this research, cultural ecology helps to test the first hypothesis that ancestral design–subsistence coherence encoded durable and sustainable spatial solutions in vernacular architecture. The biophilic design principles focus on the experiential and experiential–intuitive aspects, positing that traditional rural architecture was inherently biophilic, organically integrating natural light, airflow, vegetation, and materials. Such a biophilic lens provides both a diagnostic tool to identify lost or attenuated connections to nature in hybrid forms and a normative guide to re-establish those connections in ethically and ecologically coherent ways. Testing whether historic Lithuanian homesteads exhibit biophilic elements, and whether such features were subsequently diminished, supports the first hypothesis that hybrid interventions could be designed, grounded in ancestral biophilia. The environmental ethics frameworks offer a moral–philosophical gradient for interpreting shifts in values toward the living environment and help to contextualize motivations, from resource-centered survival to a broader recognition of non-human agency. Tracking ethical stage shifts in the discourse of stakeholders reveals how moral orientations influence decisions about landscape, material reuse, and non-human inclusion, thereby testing the aspect of the second hypothesis concerning the formation of regenerative transformation trajectories. The ecological aesthetics perception stages allow for a deep interrogation of perception, as M. DeKay [

21] identifies successive levels of ecological aesthetic awareness, from basic visual appreciation to ecological and evolutionary process awareness. Applying this framework can help to discern whether hybridization has overlooked subtler sensory and experiential aesthetic layers. This helps to test the second hypothesis and to theorize new design interventions that engage users in deeper ecological perception and aesthetic co-creation with ecosystems.

Together, when integrated in the analytical framework (

Figure 3), these approaches form an interlocking analytical schema: cultural ecology grounds sustainability from historical and functional points of view; the environmental ethics framework interprets changes in moral orientation; biophilia focuses on the vital, affective bond with nature; and ecological aesthetics targets sensitivity to nuanced layers of perception.

Although the four frameworks are presented separately, their analytical potential lies in their intersections. When applied to the same set of empirical data, they reveal complementary dimensions of the homestead: cultural ecology uncovers the subsistence-based origins of practices; environmental ethics highlights the moral orientations guiding these choices; biophilic design traces their experiential and psychological effects; and ecological aesthetics situates them within evolving perceptions of beauty and ecological harmony. Thus, together, they generate new insights by showing how necessity, value, experience, and perception converge in shaping sustainability aesthetics (

Figure 4). This integrative perspective may also support innovative hypotheses, for example, that biophilic elements mediate between subsistence practices and aesthetic appreciation, or that ecological values strengthen the resilience of sustainable aesthetic forms.

3. Case Study Object and Research Methodology

Case Study Object: The heritage homestead selected for this research is located in the central part of Čekiškė town, Kaunas district. The historical trajectory of the analyzed homestead in Čekiškė town thus reveals critical insights into the broader cultural and socio-economic transformations affecting wooden heritage architecture in Lithuanian villages and small towns, such as Čekiškė, the current population of which is less than 600 people. This homestead represents a characteristic example of wooden architecture of Lithuania, characteristic not only to the villages but also to small towns and even historic urban districts, affected by deep cultural and historical transformations. Various aspects of Čekiškė town history were analyzed by Lithuanian researchers, starting from general history [

23], and including urban development [

24], toponyms [

25], residents, and Jewish history [

26]. However, individual historic buildings of this town, especially those that are not outstanding landmarks, although providing information regarding the histories of the local population, still deserve additional interest from researchers.

The choice of this homestead as the object of analysis is justified by its dual qualities of typicality and uniqueness. On the one hand, it represents a characteristic example of Lithuanian wooden residential architecture of the early 20th century, thus making it broadly representative of rural–urban hybrid environments of its period. On the other hand, its location in a protected urban heritage area and its layered history of communal use, neglect, and prospective revitalization endow it with distinctive features of scholarly interest. While the qualitative, in-depth nature of this study inevitably entails some subjectivity, this is counterbalanced by the application of a structured methodological framework. Moreover, one of the authors’ insider perspectives, as both owner and researcher, enriches the analysis through an autoethnographic dimension, while still remaining grounded in systematic observation and theoretical rigor. Importantly, the study is intended as an exemplification and demonstration of a methodological approach that can be further applied and tested on a broader set of homesteads.

The homestead under analysis (

Figure 5) emerged in the early 20th century, during the interwar period, in an urban context defined by its location, adjacent to the local church and the main square of the town. Historically, the area was predominantly inhabited by the Jewish community and engaged primarily in commerce. Given its strategic and prestigious location, the homestead likely belonged to affluent and respected community members. Local historical accounts document notable residents in the vicinity, including a pharmacist, a photographer, and a teacher. The structure itself, approximately one hundred square meters in size, featured two main entrances facing the street, indicative of its mixed residential–commercial use. Oral histories of the town mention the Amonaičiai family, who initially inhabited the homestead, operating an agricultural products shop from within. The relationship of the residents with their environment during this period was largely homocentric, with the surrounding landscape predominantly serving human-centered needs.

The architectural and structural details suggest economic limitations or possibly unskilled construction methods relative to other buildings of the same era on the same street. Unlike nearby structures, built with solid foundations with deep cellars, this house was erected on loosely piled, small stones, resulting in significant subsidence over time, further exacerbated by the raised street level. Despite its size and the presence of four stoves, indicative of extensive living and functional spaces, the building experienced inconsistent maintenance due to its division into communal apartments during the Soviet nationalization period. The homestead, known colloquially as “the teachers house,” hosted educators and professionals working at the local school and collective farm, reflecting broader social and economic transformations occurring during the Soviet era.

The post-war period saw the original residents of the homestead replaced. Subsequent inhabitants, however, largely retained the original layout and mixed-use function of the property, even as the building deteriorated due to limited financial resources and divided responsibilities among multiple occupants. Changes in ownership and occupancy significantly altered the appearance and function of the homestead, especially from the 1970s onwards, with renovations such as the installation of secondary structures and the replacement of original doors and windows with newer, often incompatible materials.

Currently, the homestead remains an example of residential wooden architecture, exhibiting authentic elements despite its deteriorating condition (

Figure 4). Original decorative wooden elements are preserved, primarily on the attic window frames and some of the exterior doors. A few remaining original features, such as shutters and traditional stoves, testify to the historical authenticity of the object. Its garden, although neglected, maintains remnants of its original layout, including mature ash trees marking property boundaries and surviving decorative shrubs and flowers, indicating past efforts towards aesthetic landscaping. However, recent decades have seen limited and somewhat superficial maintenance interventions, such as repainting the exterior walls in the late 20th century. Crucial structural repairs, particularly concerning the leaking asbestos roof, remain unaddressed. The interior exhibits severe deterioration, with flooring inadequately patched and insulated, walls covered with multiple layers of wallpaper obscuring the original wooden structures, and the decorative elements that were prevalent in the latter half of the 20th century. At present, the homestead is largely uninhabited and in a deteriorating state, with only occasional use for storage, which justifies the necessity of intervention.

Significantly, this homestead is part of a protected urban heritage area, requiring sensitive and contextually appropriate restoration interventions. Nonetheless, the local residents often undervalue such heritage, frequently choosing modern, incompatible materials and solutions driven by personal aesthetics rather than historical authenticity and ecological sensitivity.

Three distinct development phases emerge from the history of this homestead: an initial period reflecting functional, homocentric attitudes; a subsequent phase characterized by forced collective management and fragmented ownership; and the contemporary period, marked by neglect and superficial modernization. These phases illustrate changing human–environment relations, shifting from collective and utilitarian to more egocentric approaches characterized by immediate convenience rather than long-term sustainability, which are further detailed in the Results section.

Research Methodology and Process: While

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 outline a broader range of possible methods, in this study a more focused set of methods was applied: an analysis of archival documents and the literature, detailed on-site observations and photographic documentation, a review of satellite imagery available through online platforms to trace changes in the homestead plot, and informal conversations with local community members. However, as local memories were often fragmented and at times contradicted archival evidence, the primary sources for this research were archival records, the literature, and systematic observation.

The research did not employ formal coding procedures typical of content analysis but relied on systematic qualitative observation and documentation. Fieldwork involved taking structured notes, producing photographic records, and drawing analytical schemes and site layouts to capture spatial and aesthetic qualities. Archival sources were cross-checked with direct observations and informal conversations with local residents, allowing for a triangulation of perspectives. Data processing was iterative, involving the construction of mind maps and brainstorming sessions to identify thematic connections across historical, material, and experiential layers. This interpretive strategy is consistent with qualitative heritage research approaches that emphasize contextual sensitivity, reflexivity, and creative visualization rather than formalized coding [

27]. The combination of archival analysis, visual documentation, and observation thus ensured methodological transparency while acknowledging the tacit, experiential dimensions central to this case study.

Each of the four theoretical frameworks was operationalized through guiding analytical questions (see

Figure 3). These questions served as tools for examining both historical and present-day features of the homestead. For example, cultural ecology was applied by tracing subsistence practices and material adaptations identified in archival sources and on-site observations; environmental ethics was used to classify attitudes evident in ownership patterns and land use changes; biophilic design was assessed through inventorying spatial and sensory connections to nature; and ecological aesthetics was examined by situating design features within successive levels of aesthetic perception. These theoretical criteria were applied systematically to the documented material (photographs, drawings, archival descriptions), and the synthesized results are summarized in

Table 1.

4. Results

The heritage homestead under analysis, located centrally within Čekiškė town, provides a good example of Lithuanian wooden residential architecture, its historical transformations, and the challenges that this mundane, quotidian, and often invisible heritage is facing. As mentioned above, its historical development can be structured into distinct periods, each offering insights into cultural ecology, environmental ethics, biophilic design, and ecological aesthetics (

Table 1,

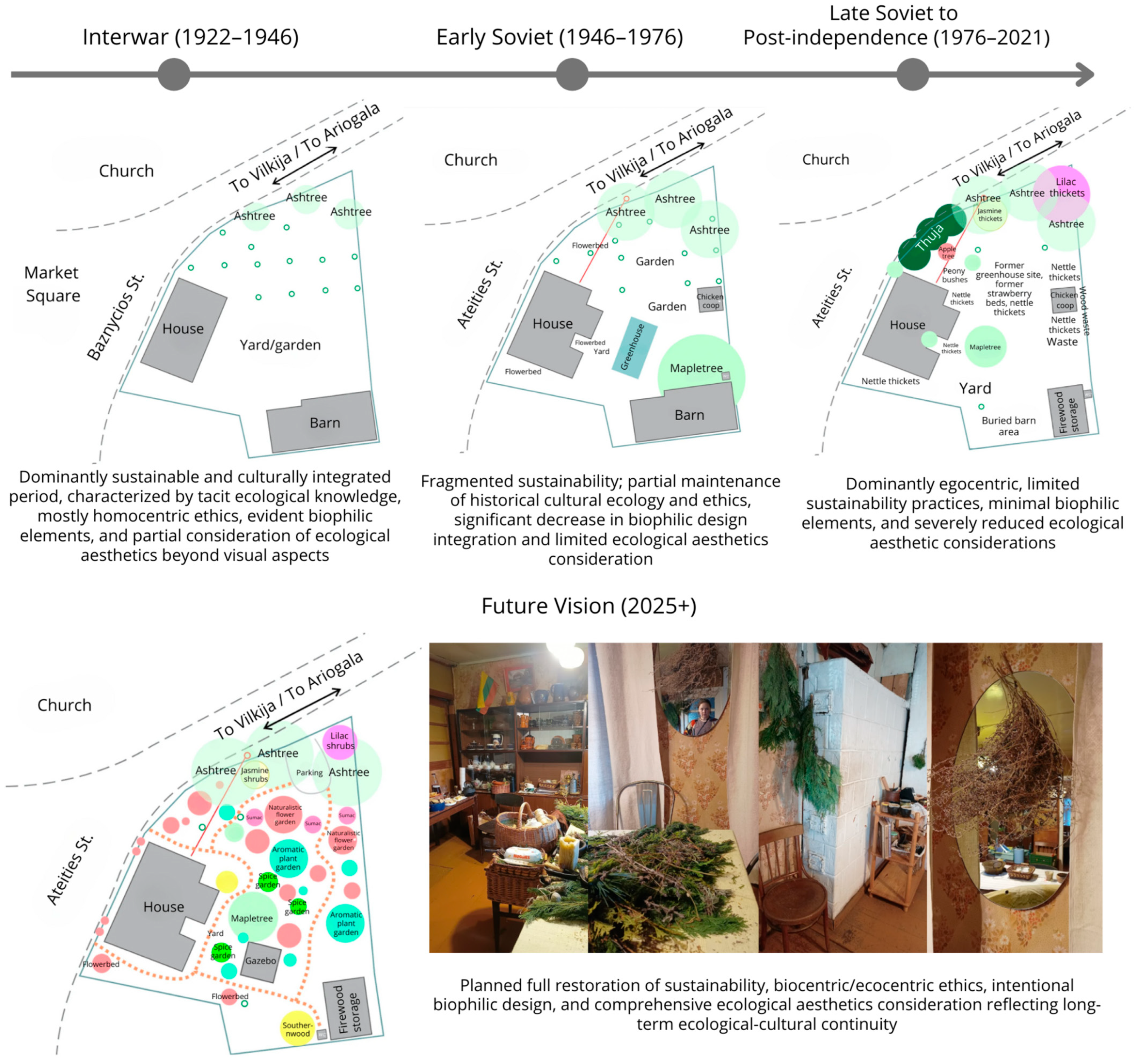

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

The interwar period (1922–1946) saw the establishment of the analyzed homestead in a then central and locally prestigious urban context, characterized by a mixed residential–commercial function, evident from its two main entrances onto the street. Cultural ecology analysis reveals a functional spatial organization driven by subsistence practices, commerce, and communal living. Historically sustainable technologies were modest due to economic constraints, reflected in the rudimentary stone foundations and absence of cellars. Homocentric ethical attitudes prevailed, as the homestead primarily served human-centered needs. Biophilic patterns were likely subconscious, involving gardens, boundary trees, and decorative shrubs, emphasizing tacit aesthetic knowledge. The ecological aesthetics was predominantly visual and phenomenological, evident from the archival records of a coherent facade and sensory considerations like functional shutters and stove heating.

The early Soviet period (1946–1976) introduced significant changes driven by forced collectivization and nationalization. The homestead was divided into communal apartments, altering both spatial arrangements and social structures. Cultural ecology points to the adaptation of spaces to accommodate multiple households, leading to fragmented maintenance practices. Environmental ethics shifted subtly toward egocentric behaviors, driven by economic hardship and social pressures, diminishing communal stewardship. The biophilic connection weakened, though incidental interactions with nature persisted through basic gardening and subsistence agriculture. Ecological aesthetics remained primarily visual and phenomenological, though deteriorating maintenance compromised sensory qualities.

From late Soviet times to post-independence (1976–2021), the homestead witnessed further functional fragmentation and structural deterioration. Cultural ecology highlights increasingly individualized adaptation strategies, reflecting changing social and economic conditions. Egocentric environmental ethics dominated, characterized by superficial maintenance such as inappropriate modern materials and neglect of historical features. Biophilic elements markedly diminished, reducing ecological awareness and the residents’ connection with the environment. Ecological aesthetics became increasingly neglected, restricted primarily to superficial visual maintenance, with little attention to phenomenological or deeper ecological considerations. The few surviving authentic features, decorative wooden elements, original doors, and mature vegetation, remained as tangible evidence of past aesthetic integrity.

Looking forward, the envisioned future stage, starting from 2025, proposes transforming the homestead into a private museum and educational venue emphasizing artistic sustainability and ecological aesthetics. Cultural ecology suggests reintroducing sustainable technologies and spatial arrangements reflecting historical authenticity, complemented by contemporary sustainability standards. Environmental ethics would shift toward biocentric and ecocentric attitudes, prioritizing ecological resilience and biodiversity enhancement. Biophilic design would consciously reinstate natural connections through native planting schemes, sensory gardens, and materials fostering direct engagement with nature. Ecological aesthetics would move beyond the visual, embracing processual, ecological, and evolutionary perceptions through educational and experiential interventions highlighting long-term ecological transformations and historical continuity (

Table 1,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

According to this vision, the approximately 100-square-meter building will have its two main entrances facing the street reopened, while additional doors will facilitate access to the garden. Essential structural renovations will include restoring the original stoves, implementing modern electrical heating, and introducing water-supply and sewage systems. The original internal doorways will be reopened to improve ventilation and the microclimate. Functional spaces will be carefully developed, including a minimal kitchen, herb-drying area, ceramic kiln, pottery wheel, and graphics press. A fiber-optic internet connection and office workspace will be established, with prospects for future coworking spaces. Internally, the historical spatial configurations from the interwar period will be reinstated, transforming the former owner’s bedroom into a staff rest area and repurposing the street-facing room as an office. The former living room will become a publicly accessible space for educational programs. The attic will be adapted for storage. During the planned renovation, hazardous materials, including the deteriorated asbestos roof, will be safely removed and replaced with ecologically and historically compatible solutions. In this envisioned transformation, the building will be adapted for educational and cultural purposes with a low-carbon approach, including the integration of energy-efficient heating, improved insulation using natural materials, and the reuse of existing structural elements wherever possible. This strategy aims to minimize carbon emissions while retaining historical authenticity. In terms of intangible heritage, oral histories and local memory reveal that the house was once known as the “teachers’ house,” symbolizing its role as a locus of community life and everyday culture. The proposed future use seeks to revive this role by hosting knowledge-sharing activities and artisanal practices. Comparable Lithuanian examples, such as the homestead Pagulbis [

16], demonstrate how heritage houses can be sensitively adapted for rural tourism while preserving the spirit of place through sustainability aesthetics, though many other transformations unfortunately risk diminishing its authentic character and weakening the bond between heritage and landscape.

Sustainability and local traditions will guide landscaping decisions: the garden will be partially replanted with cherry and plum trees, supplemented by additional currant bushes, aromatic herbs, ornamental trees, and shrubs. Paths and a pavilion for educational activities will enhance the landscape experience.

Driven by humanism, empathy, and respect for ethnic traditions, the homestead will actively foster knowledge exchange, community interaction, and local artisanal production. As a vibrant exchange hub, it will host activities related to crafts, agriculture, and local produce. Through sensitive and historically informed adaptive reuse, the Čekiškė homestead aims to become a meaningful cultural and economic center, generating opportunities for local employment and community revitalization.

The results of the analysis of the homestead are summarized in the matrix (

Table 1) and in the timeline (

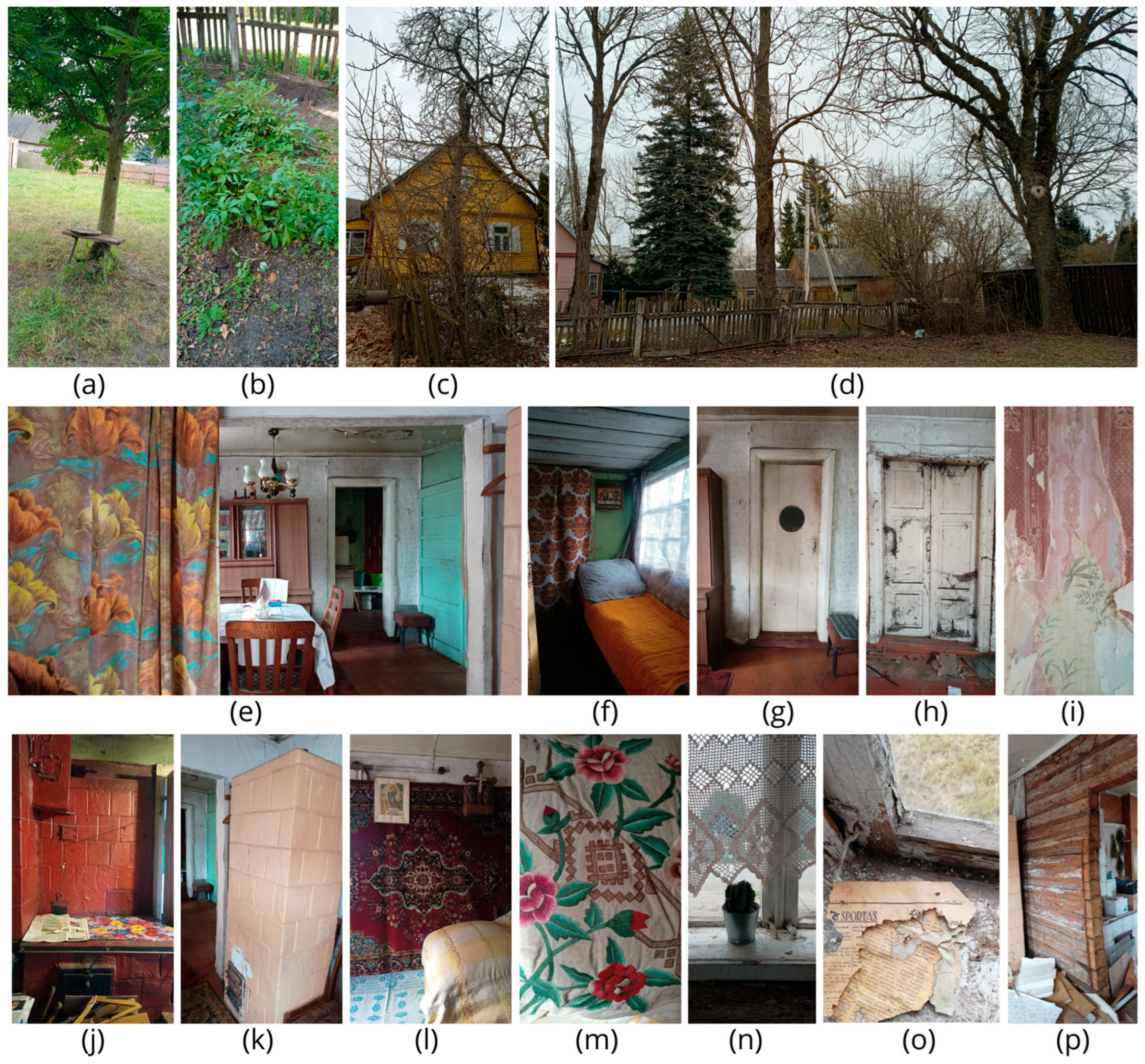

Figure 7). The photographic documentation of the homestead presented in

Figure 6 reveals often overlooked details of everyday history, from garden structures and interior furnishings to wall finishes and decorative textiles, highlighting the tacit cultural and aesthetic layers that underpin sustainability in vernacular heritage. The analytical matrix and timeline were constructed by synthesizing insights from the four theoretical frameworks—cultural ecology, environmental ethics, biophilic design, and ecological aesthetics—as applied to the four chronological stages of the development of the homestead in Čekiškė. In the analytical matrix, each theory was operationalized into three guiding questions, reformulated into binary evaluative statements answerable with “Yes,” “Partially,” and “No”. The matrix reflects a cross-stage evaluation of spatial, ethical, sensory, and aesthetic transformations, grounded in the case study analysis and supported by historical and observational data. The timeline in

Figure 5 visualizes the transformations of the homestead and presents drawings of the homestead layout in different development periods, as well as the layout of the vision of future management and development of the homestead.

5. Conclusions

Both research hypotheses raised in the introductory section were confirmed by the study: first, that sustainable management and aesthetic expressions in heritage homesteads are underpinned by nuanced, tacit layers of cultural meaning, historical practice, and informal knowledge; and second, that sustainability aesthetics emerge incrementally, only becoming fully visible when both tangible and intangible dimensions are explored. The analytical framework, comprising cultural ecology, environmental ethics, biophilic design, and ecological aesthetics, proved to be a multi-scalar toolbox, effectively capturing a diversity of aspects, from material adaptation and moral cognition to perceptual experience and design expressions. This framework facilitated in-depth case study, revealing the complex interplay between architecture, ecology, and ethics across the historical evolution of the homestead in historic Čekiškė town.

This research adds a new, multidimensional perspective to the field of sustainability aesthetics, especially within rural heritage contexts. By emphasizing time-depth, it bridges the temporal gap between the past and present, enabling the rediscovery and revival of once-lost sustainable practices and aesthetic tendencies. Practically, it offers a rigorous, heritage-informed model for innovation, potentially extending well beyond Lithuania to other rural settings worldwide. It demonstrates how integrating historical sensitivity, ecological literacy, and aesthetic intentionality could support meaningful adaptive reuse and village revitalization.

The findings of this research may have both practical and theoretical applications. Practically, the analytical framework could be applied for the development of guidelines for the sensitive transformation of homesteads, helping owners, planners, and heritage practitioners to balance authenticity with contemporary sustainability requirements. From a theoretical point of view, it contributes to a deeper understanding of everyday heritage, revealing how both visible and invisible cultural–ecological forces shape transformations over time. At the same time, the study has some limitations: it is based on a single case and thus cannot be generalized without caution, and some reliance on subjective interpretation, including autoethnographic reflection, is inherent to qualitative inquiry.

These limitations, however, open pathways for future comparative and multi-sited studies that would further test and refine the framework. While this study provided comprehensive insights in a single case, broader generalization requires comparative analysis across multiple homesteads and regions. Future research may also benefit from deeper quantitative ecological assessments and visitor perception studies to complement qualitative analysis. Moreover, the envisioned future stage of the homestead, involving its conversion into a museum and educational venue, will require ongoing evaluation to assess whether planned interventions succeed in restoring or enhancing biocentric or ecocentric ethics, biophilic engagement, and ecological aesthetics.