Towards Stringent Ecological Protection and Sustainable Spatial Planning: Institutional Grammar Analysis of China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Policy Regulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

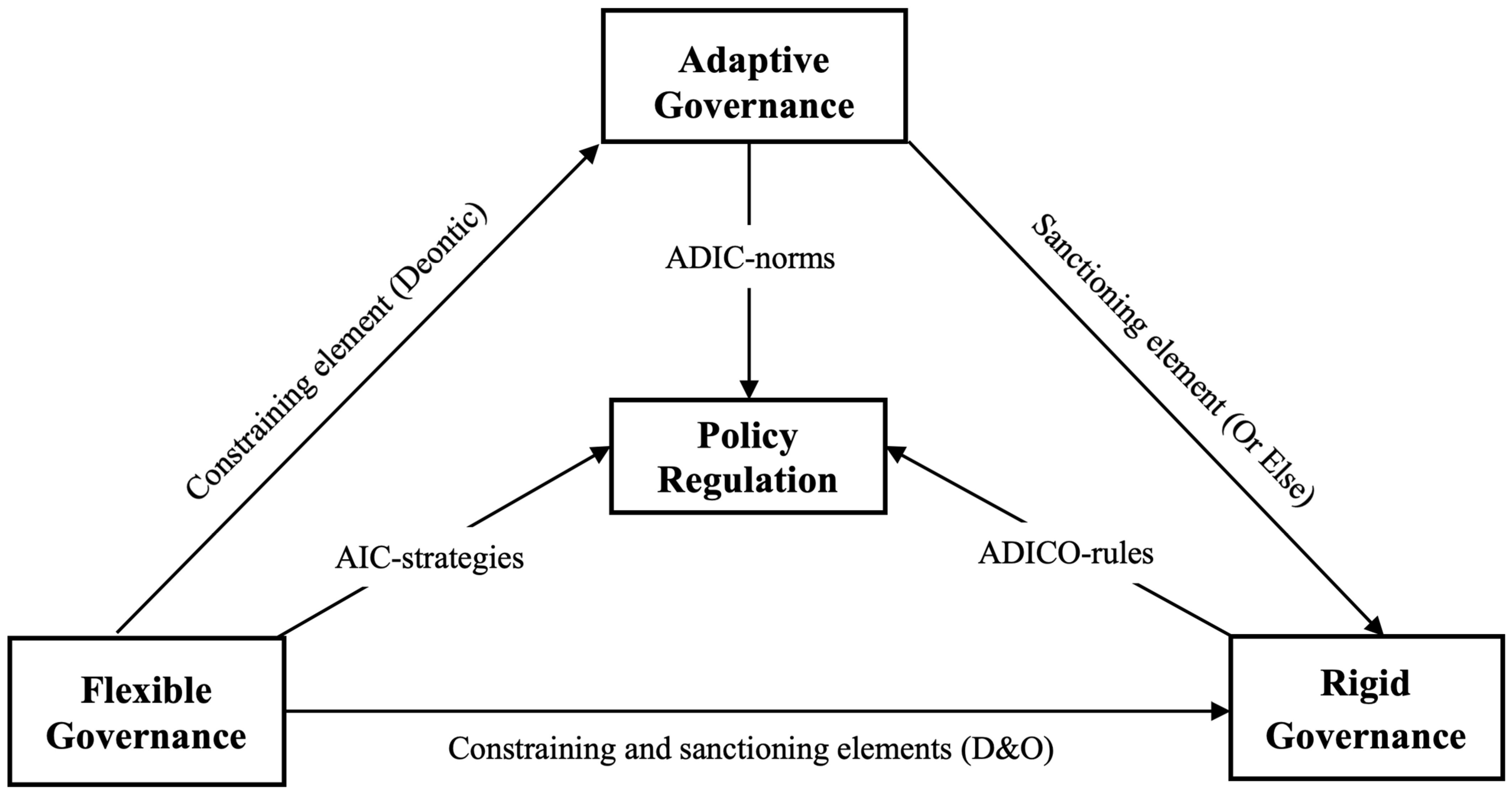

- First, it develops an analytical framework that bridges policy text analysis with institutional grammar tools (IGT) to systematically decode China’s hybrid regulatory architecture—a methodological advancement that addresses the current scholarly neglect of policy design mechanisms in land-use studies. While existing research has predominantly focused on ecological outcomes or local implementation challenges, few have dissected how regulatory instruments are grammatically constructed to balance flexibility and stringency. By applying IGT to 62 national policies, we reveal how China strategically deploys AIC, ADIC, and ADICO configurations across pathways, offering the first empirical taxonomy of regulatory intensity in land-use governance.

- Second, the study advances institutional theory by elucidating China’s distinctive calibrated rigidity approach to sustainability governance. Prior comparative studies have emphasized participatory models, overlooking how hierarchical systems like China’s integrate adaptive elements. We demonstrate that China’s system uniquely combines top-down ecological redlines (ADICO-rules) with localized experimentation (AIC-strategies), challenging the false dichotomy between command-and-control and flexible governance. This hybrid model, operationalized through grammatical variations in policy texts, provides a blueprint for emerging economies facing similar urbanization-environment tensions.

- Third, the research provides critical insights into the policy design principles that enable simultaneous achievement of ecological protection and development goals. Existing studies often treat these objectives as trade-offs, failing to examine how regulatory architecture can reconcile them. Through our IGT analysis, we identify three key design principles: (1) spatially targeted application of regulatory stringency based on ecological sensitivity, (2) strategic coupling of binding rules with flexible implementation mechanisms, and (3) dynamic monitoring systems that maintain policy coherence while allowing local adaptation. These findings offer policymakers a framework for designing land-use governance systems that can balance environmental and developmental priorities in diverse contexts, moving beyond theoretical debates to practical solutions grounded in institutional grammar analysis.

2. Literature Review

2.1. China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Policy: Evolution and Innovations

2.2. Critical Research Gaps and Theoretical Opportunities

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Policy Data

3.2. Methods

- (1)

- Text Analysis for Policy Pathway Identification

- (2)

- Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT) Analysis of Policy Regulations

- (a)

- Attributes (A): Identifies the actors, either individuals or groups such as central governments, sub-national governments, NGOs, or corporates, responsible for implementing policies.

- (b)

- Deontic (D): Specifies the prescriptive aspects of policy implementation, using terms like ‘must (not)’, ‘should (not)’, or ‘may (not)’ to express permissions, obligations, or prohibitions.

- (c)

- Aim (I): Highlights the primary goal or action that the policy intends to achieve.

- (d)

- Condition (C): Specifies the conditions under which the policy actions are applicable, including procedural, temporal, spatial, and other relevant contexts.

- (e)

- Or Else (O): Details the repercussions or sanctions for failing to comply with the policy.

- (i).

- AIC-strategies, which include Attributes (A), Aim (I), and Condition (C) but lack Deontic (D) and Or Else (O) elements, are seen as having lower regulatory impact but greater implementation flexibility.

- (ii).

- ADIC-norms add a Deontic component (D), increasing normative pressure and compliance incentives compared to AIC.

- (iii).

- The most comprehensive, ADICO-rules, encompass all five elements, including explicit sanctions (Or Else), making them the most binding and enforceable regulatory form with the highest compliance rates.

4. Results

4.1. Policy Pathways in China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Governance

4.2. Deconstruction of Policy Regulation Within Different Land Use Pathways

- (1)

- AIC-Strategies: Enabling Local Adaptation through Flexible Policy Design

- (2)

- ADIC-Norms: Balancing Central Guidance with Regional Discretion

- (3)

- ADICO-Rules: Ensuring Compliance through Binding Regulatory Frameworks

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Contributions of Hybrid Governance Mechanisms

- (1)

- AIC-Strategies and Flexible Governance: Enabling Local Innovation for Sustainable Spatial Planning

- (2)

- ADIC-Norms and Adaptive Governance: The Art of Balanced Regulation

- (3)

- ADICO-Rules and Rigid Governance: The Non-Negotiables of Ecological Civilization

5.2. Policy Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Agenda

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, C.; Richardson-Barlow, C.; Fan, L.; Cai, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z. Towards organic collaborative governance for a more sustainable environment: Evolutionary game analysis within the policy implementation of China’s net-zero emissions goals. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, S.; Lutz, E. Making housing affordable? The local effects of relaxing land-use regulation. J. Urban Econ. 2024, 143, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wong, C.P.; Jiang, B.; Hughes, A.C.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q. Developing China’s Ecological Redline Policy using ecosystem services assessments for land use planning. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Sharifi, A.; Aina, Y.A.; Ahmad, S.; Mora, L.; Filho, W.L.; Abubakar, I.R. Charting sustainable urban development through a systematic review of SDG11 research. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, C.; Richardson-Barlow, C. Assessing Policy Consistency and Synergy in China’s Water–Energy–Land–Food Nexus for Low-Carbon Transition. Land 2025, 14, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, B. The German Verkehrswert (market value) of land: Statutory land valuation, spatial planning, and land policy. Land Use Policy 2024, 136, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, P.F.; Bull, J.W.; Bicknell, J.E.; Oakley, J.L.; Brown, M.H.; Bruford, M.W.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Carr, J.A.; Church, D.; Cooney, R.; et al. The positive impact of conservation action. Science 2024, 384, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, X.; Chen, Z.; He, M. Evaluating the sustainable development goals within spatial planning for decision-making: A major function-oriented zone planning strategy in China. Land 2024, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Fang, C.; Chen, W.; Zeng, J. Urban-rural land structural conflicts in China: A land use transition perspective. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zou, C.; Zhang, K.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y. The establishment of Chinese ecological conservation redline and insights into improving international protected areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Territory spatial planning and national governance system in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Wei, Z. The border effect on urban land expansion in China: The case of Beijing-Tianjing-Hebei region. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waoo, A.A. Sustainable Development Goals; Forever Shinings Publication: Gurugram, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, M.R. The Role of Environmental Laws in Sustainable Development: A Focus on India. In Environmental Science: Interdisciplinary Approaches and Emerging Trends; Nature Light Publications: Pune, India, 2024; pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanusch, M. (Ed.) A Balancing Act for Brazil’s Amazonian States: An Economic Memorandum; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- China’s Land Administration Law. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn/c2/c30834/201909/t20190905_300663.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- China Has Basically Established a ‘Multi-Plan Integration’ Territorial Spatial Planning System. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202505/content_7024468.htm (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Notice on Strengthening the Management of Ecological Protection Redlines. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk10/202208/t20220822_992127.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Nielbo, K.L.; Karsdorp, F.; Wevers, M.; Lassche, A.; Baglini, R.B.; Kestemont, M.; Tahmasebi, N. Quantitative text analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2024, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Zhenhua, Z.; Zhou, C. Towards a just Chinese energy transition: Socioeconomic considerations in China’s carbon neutrality policies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 119, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrino, A. Comparing qualitative and quantitative text analysis methods in combination with document-based social network analysis to understand policy networks. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 2543–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongsakul, V.; Chintrakarn, P.; Papangkorn, S.; Jiraporn, P. Climate change exposure and dividend policy: Evidence from textual analysis. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2024, 32, 475–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.E.; Ostrom, E. A grammar of institutions. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1995, 89, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basurto, X.; Kingsley, G.; McQueen, K.; Smith, M.; Weible, C.M. A systematic approach to institutional analysis: Applying Crawford and Ostrom’s grammar. Political Res. Q. 2010, 63, 523–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiki, S.; Weible, C.M.; Basurto, X.; Calanni, J. Dissecting policy designs: An application of the institutional grammar tool. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiki, S.; Heikkila, T.; Weible, C.M.; Pacheco-Vega, R.; Carter, D.; Curley, C.; Deslatte, A.; Bennett, A. Institutional analysis with the institutional grammar. Policy Stud. J. 2022, 50, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, W.; Richardson-Barlow, C. Navigating ecological civilisation: Polycentric environmental governance and policy regulatory framework in China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 128, 104347. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, C.A.; Kamkhaji, J.C.; Radaelli, C.M. A sleeping giant awakes? The rise of the Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT) in policy research. J. Chin. Gov. 2019, 4, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qian, Z. Pathways of China’s carbon peak and carbon neutrality policies: A dual analysis using grounded theory and the institutional grammar tool. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. Chinese Ecological Modernisation: Source Examination and Theoretical Construction. Qinghai Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, R.; Loginova, J.; Sharma, V.; Zhang, Z.; Qian, Z. Institutional Log. Carbon Neutrality Policies China: What Can We Learn? Energies 2022, 15, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, A.; Wang, J.; MacLachlan, I.; Zhu, L. Modeling the trade-offs between urban development and ecological process based on landscape multi-functionality and regional ecological networks. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 2357–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartlinger, I.; Gualini, E. Climate governance experiments: Current practices and their meta-governance embedding in Berlin’s solar energy transition. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2025, 33, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions and the Performance of Economies Over Time. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Ménard, C., Shirley, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsnes, M.; Loewen, B.; Dale, R.F.; Steen, M.; Skjølsvold, T.M. Paradoxes of Norway’s energy transition: Controversies and justice. Clim. Policy 2023, 23, 1132–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, P.; Carpintero, Ó.; Buendía, L. Just transitions to renewables in mining areas: Local system dynamics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 189, 113934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, T. Adaptive governance. In Handbook on Theories of Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 580–591. [Google Scholar]

- Termeer, C.J.; Dewulf, A.; Van Lieshout, M. Disentangling scale approaches in governance research: Comparing monocentric, multilevel, and adaptive governance. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q. The functional evolution and dynamic mechanism of rural homesteads under the background of socioeconomic transition: An empirical study on macro-and microscales in China. Land 2022, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qian, Z.; Han, Z. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Post-Relocation Support Projects for Reservoir Resettlement: Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 167, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. Environmentality unbound: Multiple governmentalities in environmental politics. Geoforum 2017, 85, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; He, J.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. A new framework for optimizing ecological conservation redline of China: A case from an environment-development conflict area. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1616–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Donges, J.F.; Fetzer, I.; Martin, M.A.; Wang-Erlandsson, L.; Richardson, K. Planetary Boundaries guide humanity’s future on Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Cultivated land protection and rational use in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhnova, Y. Local content policies and institutional capacity for sustainable resource management. In Handbook of Sustainable Politics and Economics of Natural Resources; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 230–241. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Pathways | Sub-Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Territorial Spatial Planning and Use Control | “Five-level, Three-category”, Multi-review Integration, Three Control Lines |

| 2 | Cultivated Land Protection and Quality Enhancement | Permanent basic farmland protection system, “Trinity” protection system, Cross-regional quota trading mechanism |

| 3 | Collective Land System Reforms | Collective-owned construction land marketization, Homestead land reform, Wasteland development |

| 4 | Construction Land Lifecycle Management | New construction land approval, Revitalization of existing construction land, Construction land standard control |

| 5 | Land Market Allocation Mechanisms | Land use “increase-decrease linkage” policy, Idle land disposition, land financing and bond |

| 6 | Ecological Protection and Restoration | Ecological protection redline system, Comprehensive land consolidation, Ecological compensation mechanisms |

| 7 | Special Zone Land Support | Land use guarantees for rural revitalization, Urban renewal land policies, Land policies for major strategic zones |

| Pathways | Deconstruction Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | ADIC | ADICO | |

| Territorial Spatial Planning and Use Control | 41 | 49 | 32 |

| Cultivated Land Protection and Quality Enhancement | 32 | 36 | 41 |

| Collective Land System Reforms | 39 | 32 | 27 |

| Construction Land Lifecycle Management | 42 | 37 | 30 |

| Land Market Allocation Mechanisms | 48 | 31 | 26 |

| Ecological Protection and Restoration | 31 | 40 | 47 |

| Special Zone Land Support | 49 | 35 | 31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Zhou, C.; Richardson-Barlow, C. Towards Stringent Ecological Protection and Sustainable Spatial Planning: Institutional Grammar Analysis of China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Policy Regulations. Land 2025, 14, 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091896

Chen Y, Zhou C, Richardson-Barlow C. Towards Stringent Ecological Protection and Sustainable Spatial Planning: Institutional Grammar Analysis of China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Policy Regulations. Land. 2025; 14(9):1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091896

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yuewen, Cheng Zhou, and Clare Richardson-Barlow. 2025. "Towards Stringent Ecological Protection and Sustainable Spatial Planning: Institutional Grammar Analysis of China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Policy Regulations" Land 14, no. 9: 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091896

APA StyleChen, Y., Zhou, C., & Richardson-Barlow, C. (2025). Towards Stringent Ecological Protection and Sustainable Spatial Planning: Institutional Grammar Analysis of China’s Urban–Rural Land Use Policy Regulations. Land, 14(9), 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091896