Abstract

[Objective] Currently, there are limitations in the understanding of rural cultural landscape: they are often perceived as material spatial entities, with a lack of exploration of their intangible elements and neglect of the isomorphism between the material and intangible elements of cultural landscapes. In the context of rural cultural revitalization, it is necessary to explore the regional protection elements of rural cultural landscapes from the perspective of isomorphism. [Methods/Process] This study employs relevant linguistic theories to extract and construct a framework for a language system with regional characteristics for rural cultural landscapes from an isomorphous perspective. By deconstructing the rural cultural landscape pattern of Jiufangou in Dawu County, it summarizes the relationships and isomorphous nature between the constituent elements of this language system. [Results/Conclusions] The study identifies eight core landscape terms. These lexical units form landscape sentences based on four typical scenarios. The study then analyzed the landscape grammatical structures of different scenarios from four dimensions and explored the deep semantic meanings and contextual rules of Jiufanggou Village’s cultural landscape. Finally, this study utilizes a schematic diagram of the “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” nested structure of the Jiufanggou cultural landscape to visually illustrate the interconnections and patterns of cultural landscape elements in Jiufanggou Village across different contexts. Building on this, the study explores the structural equivalence between the material and immaterial elements of rural cultural landscapes. Overall, the construction of a nested linguistic system for rural cultural landscapes is not only about analyzing spatial forms but more importantly about exploring the underlying logical order and traditional wisdom behind spatial creation, thereby achieving the goals of associative protection, the inheritance of diverse cultures, and the continuation of the vitality of rural cultural landscapes.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Rural cultural landscapes are the product of continuous interaction between human society and the natural environment [1,2]. They refer to composite landscapes with regional characteristics that integrate natural conditions, production activities, living environments, and customs [3,4]. Rural cultural landscapes not only reflect the human geography of a region but also record the history of human activities in rural areas and express the unique spirit of a specific rural region [5,6,7].

Chinese rural territories harbor abundant cultural landscape resources, characterized by regional specificity, cultural significance, diversity, complexity, continuity, and stability [5,8]. However, with the improvement in rural accessibility, the advancement of urbanization, the influence of globalization, and the frequent occurrence of disasters, the integrity of rural cultural landscapes faces escalating threats. This is manifested in the destruction of traditional buildings and streets, the erosion of fine cultural traditions, and the disconnection of cultural connections and governance systems [9]. Over the years, in Chinese rural cultural landscapes and ecological conservation practices, there has been a lack of a standardized design and analysis language framework to connect multiple dispersed rural cultural landscapes into an integrated landscape characterized by wholeness, integrity, continuity, and dynamism [10].

In the early 1970s, Professor Alexander of the University of California created a universal design vocabulary and syntactic diagram, which he termed “pattern language” [11]. Pattern language categorizes solutions to different problems into a set of alternative approaches, with its vocabulary representing explicit solutions to specific problems. “Each solution embodies distinct syntactic and grammatical structures [12]. Subsequently, Anne Weston Spence published her work The Language of Landscape in 1998, and Simon Bell published his monograph Landscape Schemata, Perception, and Process in 1999 [13].

However, the above landscape analysis language originated in a Western cultural context and requires the refinement and construction of a Chinese environmental model language to interpret traditional prototype environments, thereby achieving both the inheritance and transcendence of tradition [14]. Domestic scholar Meng Xiaoying distinguished between “diagrams” and “schemas” to construct a new landscape schema language framework, which interprets design characteristics, offering novel perspectives for diagrammatic expression [15]; Wang Yuncai used diagram language as a path to study the mechanisms and logical relationships of landscape space, proposing a framework for a landscape spatial language system composed of spatial vocabulary, spatial grammar, and spatial syntax [12]. Hu Weihua draws on the theories of form, meaning, and function from American semiotician Morris to conduct a comparative analysis and summary of the inheritance pathways of garden design languages in Japan, France, and the United States, exploring the creative transformation and innovative development of Chinese garden design language [16].

From the “Alexander Model Language” to the “Language of Landscape” to the “Schematic Language of Landscape Space,” the research approach and methodology for the linguistic representation of cultural landscapes have been preliminarily established. However, existing studies primarily interpret and understand cultural landscapes as material spatial entities, focusing on material elements such as constituent components, structural relationships, and formal characteristics. There is a lack of exploration into the immaterial elements of cultural landscapes, particularly in terms of expanding the cognitive dimension of the isomorphism between material and immaterial elements.

1.2. The Connotation of Cultural Landscapes Under the Concept of Isomorphism

Human geography views cultural landscapes as the result of human activities superimposed on natural landscapes, characterized by regional specificity, inclusivity, accumulation, and continuity [17]; the constructivist perspective regards cultural landscapes as the product of social interaction and subjective cognition, characterized by dynamism and symbolism [18]; ecological studies focus on the synergistic interaction between biological and cultural diversity, and propose the concept of “biocultural landscapes” to integrate material resources with intangible cultural values [19]. Therefore, the essence of the concept of cultural landscapes lies in the isomorphic relationship between cultural and natural elements.

The concept of isomorphism originated in the field of mathematics, where it is used to describe the mapping relationship between mathematical objects, indicating that certain elements in one set correspond to certain elements in another set [20]. Subsequently, the concept of isomorphism has been adapted and applied across various disciplines, such as logical isomorphism in philosophy [21], phonological–semantic isomorphism in linguistics [22], heterogeneous–esthetic isomorphism in psychology [23], and topological isomorphism in spatial form [24]. From the definitions of the concept of isomorphism across different disciplines, its core essence lies in the fact that objects share the same or similar structures and compositional logic, with their internal elements mutually influencing each other to form a unified whole. This closely aligns with the concept of cultural landscapes.

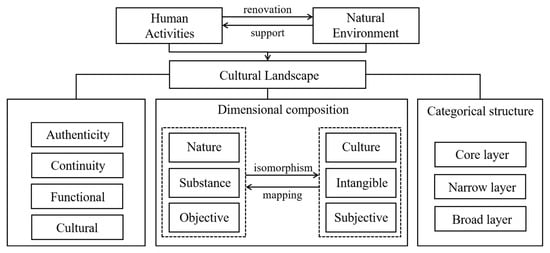

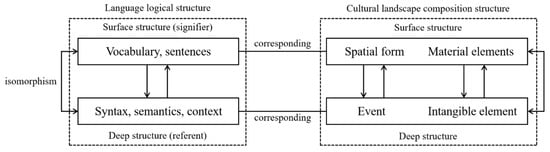

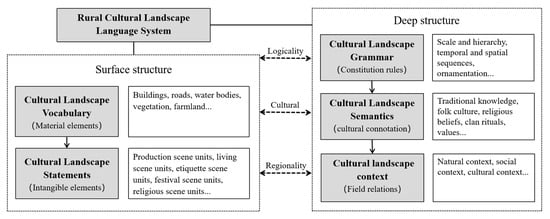

This isomorphic relationship manifests itself in the synergy between material and immaterial elements [17,19] and the symbiosis between production and lifestyle and rural space [25]. Both are indispensable and together constitute rural cultural landscapes. Based on this, under the concept of isomorphism, the connotation of cultural landscape is reinterpreted, and a conceptual framework (Figure 1) is constructed, which includes characteristic attributes, dimensional components, and categorical structure.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for Cultural Landscape Isomorphism.

1.3. The Linguistic Logic of Rural Cultural Landscapes

Language is a symbolic system that combines sound and meaning, possessing two fundamental attributes: symbolism and systematicity. First, language symbols consist of two components: the “signifier” and the “signified” [26]. The ‘signifier’ refers to the phonetic image of the language symbol, while the “signified” refers to the concept and meaning represented by the language symbol; the two are interdependent. Second, the language system operates at two levels: surface structure and deep structure. The surface structure includes subsystems such as morphemes, vocabulary, and sentences, while the deep structure includes subsystems such as grammar, semantics, and context. The “surface structure” and “deep structure” exhibit a generative transformational relationship [27].

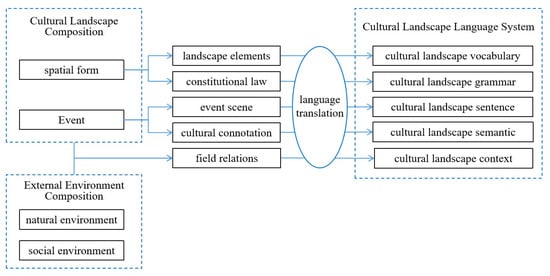

Landscape functions as a linguistic symbol system [28], the product of the interplay between natural and human language [29]. Landscape possesses all the characteristics of language, encompassing the words and structure of discourse—shape patterns, structure, materials, form, and function. All landscapes are composed of these elements, similar to how word meanings emerge only within context [30]. Therefore, the cognitive expression of landscape shares consistency and isomorphism with the rules of linguistic communication instruction systems in terms of organizational principles and logical structure. By applying linguistic logical structures [15,31], cultural landscape elements can be matched and corresponded with linguistic elements, forming a linguistic analysis logic for cultural landscapes (Figure 2). Specifically, the “vocabulary” of cultural landscapes consists of the most basic landscape elements and units; the ‘sentences’ of cultural landscapes are landscape scenes composed of multiple basic elements; the “semantics” of cultural landscapes encompass the cultural connotations, value significance, and sense of place; the “context” of cultural landscapes is the field of relationships in which the subject perceives, uses, transforms, or is influenced and constrained by cultural landscapes, including the subject, time, and social background; and the “grammar” is the rules governing the combination of landscape elements, their constitutive mechanisms, and the generation of meaning [32].

Figure 2.

Linguistic logic of cultural landscape.

1.4. Study Aims

This study draws on relevant linguistic theories to extract and construct a language system for rural cultural landscapes with regional characteristics from an isomorphy perspective, providing new research approaches and methods for understanding and interpreting rural cultural landscapes.

The research objectives of this project include: (1) establishing a linguistic framework for rural cultural landscapes based on the principle of isomorphism; (2) deconstructing the spatial structure of the rural cultural landscape in Jiufanggou, Dawu County, from a linguistic perspective; and (3) summarizing the relationships and isomorphic properties among the constituent elements of the linguistic system of the Jiufanggou rural cultural landscape.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

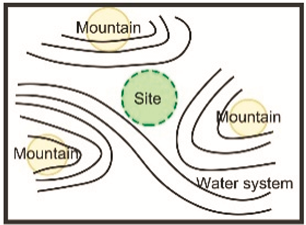

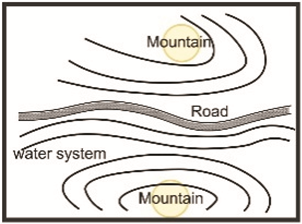

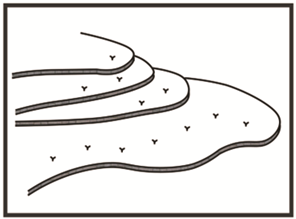

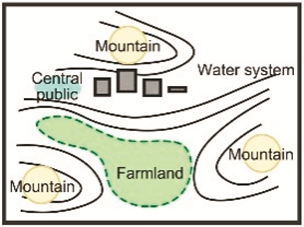

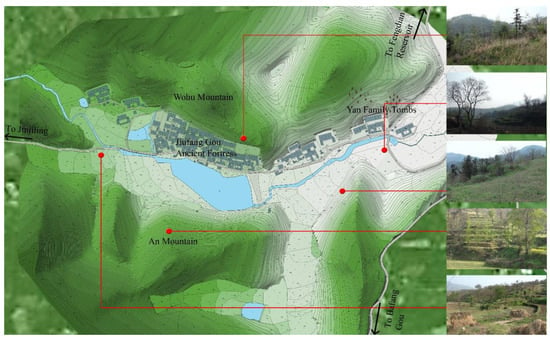

Jiufanggou Village is located in Fengdian Town, Dawu County, Xiaogan City, Hubei Province. Geographically, it exhibits the typical characteristics of an intermontane basin, nestled in the narrow, flat strip of land at the southern foot of the Dabie Mountains. The village is shielded by Zhaiji Mountain to the north, bounded by An Mountain to the south, and backed by Wohu Mountain to the north. The terrain is higher in the north and south, lower in the middle, and slopes distinctly from west to east (Figure 3). The village’s primary water source originates from mountain streams converging from Zhaiji Mountain in the west. After convergence, the streams form a west-to-east water system, flowing successively through Fengdian Reservoir and Zhugan River before ultimately emptying into the Huai River system. To address issues such as seasonal drying up and unstable water flow of the original streams, Jiufanggou Village constructed a dam in 2005, transforming the streams into ponds. These ponds serve as both a water source for villagers’ daily use and a stable irrigation water source for farmland.

Figure 3.

Topography and landforms of Jiufanggou Village.

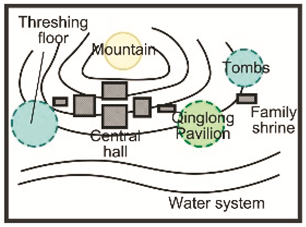

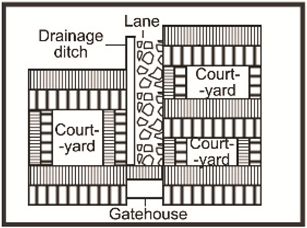

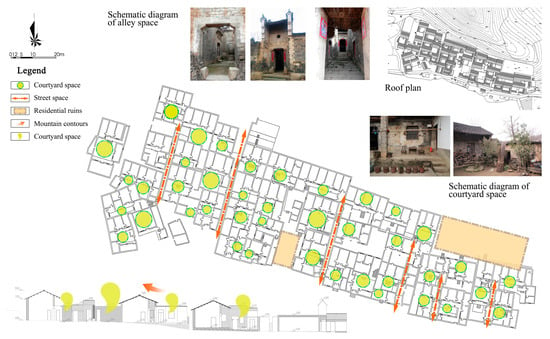

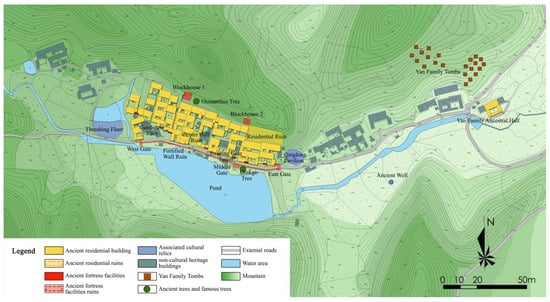

Jiufanggou Village was founded during the late Ming Dynasty by the fifth-generation ancestor of the Yan family, and has a history of approximately 400 years [33]. As the Yan family grew and prospered, it developed into the grand Jiufanggou Ancient Fortress Complex (Figure 4). The complex covers an area of approximately 10,000 square meters and consists of fortress walls, blockhouses, ancient Yan family residential courtyards, a central hall, the Yan family ancestral hall, the Qinglongtai (a clan meeting space), and a threshing floor. These spatial elements are interconnected through alleys, forming an organic and cohesive multi-courtyard spatial system.

Figure 4.

Floor plan of the ancient village architecture of Jiufanggou Village.

2.2. Methodological Framework

2.2.1. Research Framework

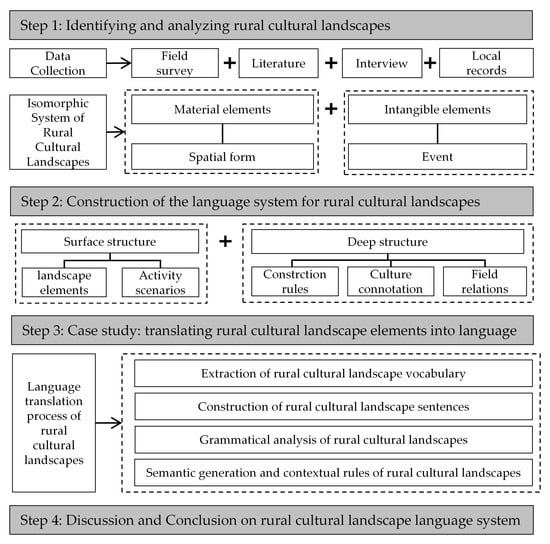

This study was carried out in four steps (Figure 5). The first step is to identify and analyze rural cultural landscapes. In this process, the isomorphic System of Rural Cultural Landscapes is an important theoretical basis. The second step is to construct the language system for rural cultural landscapes, which will be focused on in the next section. The third step is to translate the elements of rural cultural landscapes into language through a case study. The fourth step is to discuss and conclude the language system of rural cultural landscapes.

Figure 5.

Research framework.

2.2.2. Construction of a Linguistic System for Rural Cultural Landscapes

Just as in linguistics, where vocabulary, sentences, paragraphs, and texts form hierarchical and combinatorial structures, the rural cultural landscape pattern is composed of landscape elements such as buildings, roads, water bodies, vegetation, and farmland, which are arranged, combined, layered, and nested according to certain patterns to form a composite landscape system that embodies both typicality and local cultural connotations [34]. Therefore, following the linguistic logic of cultural landscapes, the rural cultural landscape language system (Figure 6) is composed of five subsystems: lexical elements, sentence elements, grammatical structure, semantic generation, and contextual rules. Lexical and sentence elements constitute the surface structure, whereas grammatical rules, semantic generation, and contextual factors form the deep structure. Within the rural cultural landscape language system, multiple cultural landscape lexical elements follow grammatical rules to form complex, nested cultural landscape compound sentences. These sentences further nest within each other under specific semantic contexts and are influenced by contextual factors, collectively constructing a multi-layered, multi-dimensional language expression system.

Figure 6.

Language system of rural cultural landscape.

The grammar of rural cultural landscapes reflects villagers’ adaptation to local conditions through long-term human-land interactions, the inheritance of traditional atmospheres, clan-based beliefs, and local cultural traditions, as manifested in daily rural construction and production and living habits [12]. The relationships within the rural cultural landscape grammar primarily include: the scales and hierarchical levels between macro, meso, and micro levels; temporal and spatial sequences; and the ornamental aspects of the landscape [35]. The same vocabulary and spatial grammar, under the constraints and supplementary roles of different spatial contexts, exhibit distinct meanings and functions [36]. Within the rural cultural landscape language system, the interplay of natural, social, and cultural contexts collectively forms the overarching esthetic framework of the rural cultural landscape [31].

This language system framework is based on the recognition of the isomorphic relationship between nature and culture and involves the schematic induction and refinement of the basic components (elements and scenes) and formation mechanisms (rules and generation) of cultural landscapes. It emphasizes that landscapes are no longer merely material spatial forms, but rather scenes where natural environments and human activities coexist, and where material elements (spatial forms) and immaterial elements (activities and events) are isomorphic. Within the same spatial form, different events and behaviors give rise to distinct spatial relationships and cultural spiritual connotations, thereby generating different nested schematic languages.

2.3. Data Collection

In terms of initial data acquisition, our efforts were divided into four categories: Literature Review, Field Surveys, Interviews, and Local Records.

In the literature research and local records collection, we have collected and organized literature and materials related to the natural geography, historical evolution, microeconomics, folk customs, and intangible cultural heritage of Jiufanggou, as well as “The Yan family genealogy” and “The Jiufanggou Village Protection and Development Special Plan”.

Four field surveys were conducted in Jiufanggou Village between 2018 and 2023. In these investigations, we comprehensively employed participatory observation methods to delve into the farmland, Yan family tombs, ancient fortress complex and streets, Qinglongtai, threshing floor, and other public spaces in Jiufanggou Village. We collected a total of 826 first-hand photographs and translated them into symbols.

Furthermore, we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with permanent residents of the village and officials from the village and township governments to obtain first-hand oral accounts on various aspects of Jiufanggou Village, including its historical evolution, socio-cultural practices, and contemporary livelihoods of its residents. We compiled a total of over 20,000 words of transcribed audio recordings. By combining the preliminary textual data with subsequent field investigation materials for analysis and verification, we ensured the completeness, validity, and scientific rigor of the research data.

2.4. Semi-Structure Interviews

Semi-structured interviews, serving as one of the core data collection methods for this research, were conducted concurrently with four field surveys between 2018 and 2023. The first round, aimed at gathering foundational information, focused on the historical context of the village, establishing an initial understanding of Jiufanggou Village’s origins and the Yan family’s developmental trajectory, thereby laying the groundwork for refining subsequent interview outlines. The second and third rounds pursued elemental deep-diving and scene reconstruction. These delved into key cultural landscape elements identified in the initial phase (such as the ancient fortress defense system, ritual spaces, and agricultural activities) through in-depth interviews. Emphasis was placed on supplementing details linking intangible cultural practices (e.g., Qingming ancestor worship procedures, Lantern Festival lion dance ceremonies) with tangible landscapes. The final session centered on supplementing and refining information, conducting secondary interviews to address ambiguities identified in the preceding three rounds (e.g., the functional evolution of street spaces, changes in water management facility usage), ensuring the validity and accuracy of the data.

The interviews employed a semi-structured design combining a core outline with flexible follow-up questions. The outline, organized around research objectives, comprised five core modules: village history and clan evolution; perceptions and functions of the material landscape; intangible cultural practices; landscape conservation and current livelihoods; and cultural significance and value recognition. Each module contained 3–5 key questions, with space reserved for follow-up inquiries to capture implicit information.

To guarantee sample representativeness and information comprehensiveness, interviewees were drawn from diverse village groups: (1) 32 permanent residents, including: 15 elderly individuals (aged 60+) primarily from the Yan family lineage, providing firsthand recollections of village history and traditional customs; 12 middle-aged individuals (aged 30–60), encompassing ordinary villagers, agricultural producers, and practitioners of traditional crafts (e.g., lion dance prop-making), reflecting the landscape’s current usage and state of transmission; 5 young adults (aged 18–30), to understand the younger generation’s perception and identification with the landscape culture. (2) Seven village and town officials were interviewed to gather official information on village planning, landscape conservation policies, and collective activity organization, alongside their impact on Jiufanggou Village, supplementing macro-level contextual data.

Each interview phase lasted 4–10 days. The initial phase, requiring comprehensive baseline assessment, had the longest duration of 10 days. Subsequent phases, with more focused objectives, were shortened to 4–7 days. Single interviews with permanent residents lasted 30–60 min, employing everyday language to guide recollection and prevent information overload. Interviews with village and town officials lasted 60–90 min, focusing on in-depth discussions of policy contexts, village planning, and current landscape conservation practices.

3. Results

3.1. Extraction of Cultural Landscape Vocabulary Elements in Jiufanggou Village

The rural cultural landscape of Jiufanggou includes both tangible and intangible elements. The tangible elements include farmland landscapes, rural roads, ancient fortress complexes, the Yan family tombs, water ponds, wells, and other water conservancy facilities, as well as ancient trees and other vegetation landscapes (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution map of cultural landscapes in Jiufanggou Village.

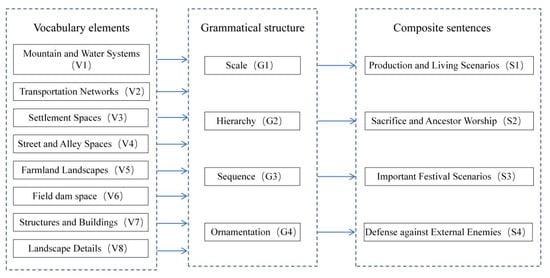

Using the rural cultural landscape language system model and through the translation of schematic language, the material elements of the cultural landscape of Jiufanggou Village can be refined into eight categories of vocabulary: “Mountain and Water Systems”, “Transportation Networks”, “Settlement Spaces”, “Street and Alley Spaces”, “Central Public Spaces”, “Farmland Landscapes”, “Structures and Buildings”, and “Landscape Details” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Schematic language of cultural landscape vocabulary elements in Jiufanggou Village.

3.2. Construction of Composite Sentences Describing the Cultural Landscapes of Jiufanggou Village

Through field research and literature review, Jiufanggou Village presents four typical types of socio-cultural practice scenarios, namely “Production and Living Scenarios”, “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship Scenarios”, “Important Festival Scenarios” and “Defense against External Enemies Scenarios”. These scenarios constitute the syntactic level of the cultural landscape language system of Jiufanggou Village.

Jiufanggou Village relies primarily on traditional agricultural production methods, and its “Production and Living Scenarios” show typical characteristics of an agricultural society. Residents’ daily activities revolve around the agricultural production cycle, forming a rhythm of “rising with the sun and resting with its setting”. This is specifically manifested in a series of agricultural activities such as sowing, transplanting rice seedlings, irrigation, harvesting, and drying grain, reflecting the temporal order and spatial characteristics of agricultural civilization.

As a multifunctional space, the rice drying field not only serves as a place for drying rice but was also historically the core venue for “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship Scenarios” of the Yan families ancestral. This tradition continues to this day, forming a ritual space for collective ancestral worship during the Qingming Festival. The Qingming tomb-sweeping custom originates from an understanding of natural rhythms: during the spring when plants begin to sprout, clan members must inspect their ancestors’ graves to ensure they have not been damaged by the rainy season and perform maintenance tasks such as weeding and adding soil. The ritual includes offering sacrifices (roasted pork, wine), burning incense and pouring libations, and burning paper money, reflecting the filial piety and ancestor worship inherent in clan culture.

The lion dance performance on the 15th day of the first lunar month, the Lantern Festival, is a typical example of “Important Festival Scenarios” in Jiufanggou Village. This folk custom features a complete ceremonial process: in the evening, villagers carry homemade lanterns along the main street in a procession, eventually gathering in front of the village’s eastern ancestral hall. After nightfall, the lion dance troupe begins their performance amid the sound of firecrackers and proceeds to tour each household along the main street. Villagers set up altars at their doorsteps, offering candles, effigies of the Wealth Deity, wine, fruits, and meat as sacrificial offerings. The lion dance performance is carried out by two people working in tandem, using a lion-shaped prop made of colored cloth, synchronized with the rhythm of drums and gongs to mimic the various movements of a lion. As an interactive element, the host family prepares cigarettes, candies, and red envelopes, which serve both as a token of appreciation for the performers and as a way to express their hopes for blessings and good fortune.

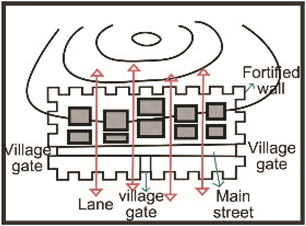

Based on historical records and spatial remains, Jiufanggou Village frequently faced the challenge of “Defense against External Enemies Scenarios” in ancient times. As a response, the ancient fortress village established a comprehensive defense system, including towering fortress walls, lookout facilities, an internal network of pathways, and military structures such as watchtowers at strategic high points. The organic integration of these defensive spatial elements formed a well-structured, functionally complete defense system, effectively ensuring the safety of the clan settlement and reflecting the spatial strategies traditional settlements employed to address social risks.

3.3. Grammatical Structure Analysis of the Cultural Landscapes in Jiufanggou Village

The linguistic system of the Jiufanggou cultural landscape comprises four grammatical structures: scale, hierarchy, spatial–temporal sequence, and ornamentation. To conduct an in-depth analysis of how cultural landscape vocabulary elements are organized into composite sentences through grammatical structures, this study first assigns numbers to the eight cultural landscape vocabulary elements, four grammatical structures, and four types of composite sentences (Figure 8). By constructing a “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” association analysis pathway, the study clarifies the matching rules between vocabulary elements and grammatical structures with different numbers, thereby reducing the nesting relationships among various compound sentences. This reveals the intrinsic logic by which cultural landscape vocabulary elements construct composite sentences through grammatical structures.

Figure 8.

Jiufanggou cultural landscape “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” coding and association analysis pathway.

Through “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” correlation analysis, we found that:

- (1)

- The spatial scale grammatical structure of the cultural landscape of Jiufanggou Village is divided into three levels: macro, meso, and micro. At the macroscale, the cultural landscape vocabulary elements include: “Mountain and Water Systems” and “Transportation Networks”, which form the overall spatial layout and ecological foundation of the cultural landscape of Jiufanggou Village; At the mesoscale, the cultural landscape vocabulary elements include “Settlement Spaces”, “Street and Alley Spaces” and “Farmland Landscapes”, reflecting the spatial characteristics resulting from the interaction between human activities and the natural environment at a certain scale; At the microscale level, the cultural landscape vocabulary elements include “Central Public Spaces”, “Structures and Buildings” and “Landscape Details”, reflecting the material form and cultural connotations of the cultural landscape at a small scale and in detail.

- (2)

- The settlement space, street and alley space, and buildings in Jiufangou Village all exhibit a clear hierarchical distinction between primary and secondary elements. In the context of “Production and Living”, the central hall, which served as the meeting hall for the Yan family, is located along the central axis of the ancient fortress; the remaining courtyards are arranged around the central hall and follow the natural terrain, with the southern part being lower and the northern part higher. Additionally, based on social status, those of higher rank reside in the higher elevations. Meanwhile, the alleyway space follows a “1 main street and 12 alleys” structure; individual buildings are divided into main houses and side rooms, with the main house serving as the core area for family activities, differing in size and architectural structure from the side rooms1. In the context of “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship”, ancestral worship ceremonies, as the most solemn form of ancestral worship, are centered around the ancestral hall as the primary spatial venue; followed by the Yan family tombs and the threshing floor2 in the courtyard, which serve the function of tomb worship; and finally, the main house, which serves the function of family worship. In the context of “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship”, ancestral worship ceremonies, as the most solemn form of ancestral worship, are centered around the ancestral hall as the primary spatial venue; followed by the Yan family tombs and the threshing floor in the courtyard, which serve the function of tomb worship; and finally, the main house, which serves the function of family worship. In the context of “Important Festivals”, the ancestral hall serves as the iconic node of the ritual space and holds a dominant position; the entrances to each courtyard form secondary spatial nodes for activities, while the main street functions as a linear spatial element, connecting all nodes to form a complete ritual space. In the context of “Defense against External Enemies”, the Jiufanggou Ancient Fortress has established a clearly defined defensive system: the outer layer of defense consists of fortress walls, gates, and blockhouses, forming the first line of defense; the inner layer of defense is achieved through a system of alleyways and gatehouses, forming the second line of defense; additionally, the mountainous terrain surrounded on three sides and facing water to the south also provides a certain advantage in defending against external enemies.

- (3)

- Regarding the spatial–temporal sequence structure of cultural landscapes, the four types of cultural landscape sentences exhibit distinct spatial expression forms. In production and daily life scenarios, villagers’ daily activities follow the circadian rhythm of “rising with the sun and resting with its setting,” while annual activities adhere to the agricultural cycle of “spring plowing, summer weeding, autumn harvesting, and winter storing.” The lexical elements involved include mountains and water systems, field paths and transportation networks, settlement spaces, farmland landscapes, open-air spaces (such as threshing floor) and so on. In the context of “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship”, ancestral worship ceremonies are held from the 23rd day of the 12th lunar month to the 15th day of the 1st lunar month; grave worship ceremonies are fixed on Qingming Festival and the 15th day of the 7th lunar month (Zhongyuan Festival); Family rituals are typically conducted on the first and fifteenth days of each lunar month, with special emphasis during grave and ancestral hall rituals; the vocabulary elements involved include the ancestral hall and Yan family tombs in settlement spaces, the threshing floor in courtyard spaces, and the main house in constructed buildings. In the context of “Important Festivals”, activities follow a strict spatial–temporal logic: the initial stage involves gathering in front of the ancestral hall, followed by a procession along the main street, and finally completing the New Year’s greetings ceremony at the entrances of each courtyard, forming a “point–line–point” spatial progression pattern. In the context of “Defense against External Enemies”, the Jiufanggou ancient fortress presents a spatial–temporal sequence relationship from the exterior (periphery) to the interior (depth); the vocabulary elements involved include the mountainous water systems, street and alley spaces, and the fortress walls, gates, blockhouses, and gatehouses of the constructed buildings.

- (4)

- The ornamentation of the Jiufanggou cultural landscape is primarily reflected in the following three areas: First, the ancient architectural complex of Jiufanggou features a color scheme combining blue-gray brick walls, gray-tiled roofs, and yellow-brown wooden structures, embodying the natural texture and rustic esthetic of traditional building materials. Second, as the primary ceremonial space (ancestral hall) of Jiufanggou, its decoration is solemn and reverent. Through auspicious patterns on architectural components, zoomorphic ornaments, and painted ceiling decorations, along with the deep wood tones and natural light, it creates a sacred and serene ceremonial atmosphere. Third, important festive scenes are enhanced with vibrant colors to evoke a celebratory atmosphere. For example, the main street is adorned with colored lights forming linear light strips, while the entrances to each courtyard feature golden and red hues—colors symbolizing good fortune in traditional Chinese culture—to collectively create a joyful and harmonious visual landscape.

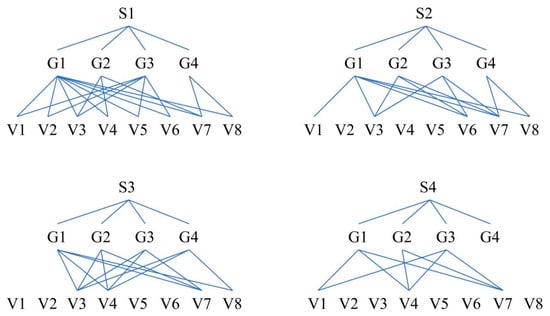

By drawing a diagram of the nested structure of the cultural landscape “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” of Jiufanggou (Figure 9), we found that in Jiufanggou Village, the cultural landscape vocabulary elements that constitute the composite sentence “Production and Living” scenes are the most numerous, followed by “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship” scenes, “Important Festivals” scenes. The cultural landscape vocabulary elements involved in “Defense against External Enemies” scenes are the least numerous, which is also positively correlated with the frequency of these scenes. The vocabulary elements most closely associated with the grammatical structure “hierarchy” are Settlement Spaces, Street and Alley Spaces, and Structures and Buildings; the vocabulary elements most closely associated with the grammatical structure “spatial–temporal sequence” are Mountain and Water Systems, Settlement Spaces, Street and Alley Spaces, Field Dam Space, and Structures and Buildings; and the vocabulary elements associated with the grammatical structure “ornamentation” are Settlement Spaces, Street and Alley Spaces, Structures and Buildings, and Landscape Details.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the nested structure of the “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” of the Jiufanggou cultural landscape.

3.4. Semantic Generation and Contextual Rules for the Cultural Landscapes of Jiufanggou Village

According to historical records, during the late Ming Dynasty, Yan Quan Gong (the ninth son of the Yan family) led his clan members from Jinjiling (now the west and southwest of Jiufanggou) over Zhaiji Mountain to settle here. Through generations of development, the settlement eventually grew to its current scale. The historical evolution of the settlement fostered a strong sense of family identity, which in turn gave rise to a systematic clan-based ideological framework. However, as the family population grew, collective memories based on blood ties gradually faded, and coupled with spatial resource constraints, later generations began to build new dwellings in surrounding areas, leading to the gradual weakening of traditional social structures. In this context, the clan hall serves as an important cultural space, preserving the collective memory of dispersed clan members [37]. Therefore, from the perspective of “semantic generation” theory, the traditional culture of Jiufanggou Village primarily manifests as a deep integration of agricultural civilization and clan-based culture.

From the perspective of “contextual rules”, the formation and development of the Jiufanggou Ancient Fortress reflect the interactive process between the Yan clan and the natural environment: initially manifested in agricultural land reclamation and house construction activities related to production and daily life; simultaneously, natural conditions and the technological level of the time significantly constrained construction activities, particularly in terms of material selection, construction techniques, and spatial dimensions for “Structures and Buildings”. As the population grew and the clan expanded, the degree of clan organization continued to increase, forming a socially structured “village clan community” with strong cohesive force. The evolution of this social structure, in turn, influenced the creation of the village space, shaping the unique “Street and Alley Spaces” form and “Courtyard Space” layout. It is worth noting that the spatial creation of the Jiufanggou Ancient Fortress was deeply influenced by both agricultural culture and clan-based culture: From the macro-scale “Mountain and Water Systems”, to the meso-scale “Settlement Spaces” structure, temporal-spatial sequence, and axis relationships, as well as the micro-scale “Structures and Buildings” and “Landscape Details”, all reflect the natural perspective of agricultural culture and the ethical concepts, ancestor worship, and ritualistic hierarchical ideas of clan culture. This cultural influence’s spatial manifestations constitute the unique cultural landscape system of the Jiufanggou Ancient Fortress.

Moreover, through semi-structured interviews, we gathered the following information: the traditional architectural spaces of Jiufanggou Ancient Fortress no longer adequately accommodate villagers’ modern living requirements, particularly lacking essential infrastructure such as bathrooms. Some residents have altered or even demolished and rebuilt traditional dwellings to expand living space, causing some damage to the rural cultural landscape.

Currently, villagers primarily earn their livelihood through migrant work, with only a few elderly residents remaining to engage in traditional farming activities. Consequently, young people are rarely seen in many traditional production and daily life settings. Simultaneously, certain ritual and festive practices are gradually disappearing, with only major events like Qingming Festival ancestor worship and Spring Festival lion dances persisting. Moreover, the younger generation exhibits limited acceptance of traditional customs and little inclination to preserve intangible cultural heritage. In contrast, the village elders demonstrate stronger commitment to safeguarding ancient fortress structures and ancestral halls, alongside deeper appreciation for the cultural landscape’s intrinsic value.

To advance the conservation of Jiufanggou’s cultural landscape more effectively, the local government has actively applied for designation as a National Traditional Village and engaged specialists to formulate a preservation plan. However, constrained by insufficient funding, the current state of protection for Jiufanggou’s ancient fortified villages remains unsatisfactory, with the preservation quality of a significant portion of the structures causing concern. Consequently, village and town officials propose developing distinctive agriculture and rural tourism to drive both the cultural landscape conservation and the overall development of Jiufanggou Village.

4. Discussion

Through literature review, we found that current research primarily employs two approaches to analyze rural cultural landscapes: spatial pattern language or diagrammatic language. Spatial pattern language focuses on typological methods to summarize the diverse spatial patterns of rural cultural landscapes, with patterns at different scales forming nested structural relationships [11]. Spatial pattern diagrams tend to emphasize the representation of three-dimensional spatial scenes [38]. Diagrammatic language often employs a tree-like structure to intuitively reflect the relationships between vocabulary, grammar, and context, with spatial patterns primarily based on two-dimensional planar spatial structures [12,34,39,40]. However, regardless of whether spatial pattern language or diagrammatic language is used, research in cultural landscape analysis often prioritizes the material dimension. Even when analyzing cultural connotations from a contextual perspective, there is often a relative disconnect between material and immaterial dimensions.

This study constructed a linguistic system for rural cultural landscapes and, using Jiufanggou Village as an example, summarized a research path for transitioning from cultural landscape diagram research to linguistic system research (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

A roadmap for transitioning from cultural landscape diagram research to language system research.

Unlike traditional studies on spatial mode languages and diagrammatic languages [12,13,14,15], this research focuses on the isomorphism between the material and immaterial aspects of cultural landscapes. Our analysis revealed an intriguing phenomenon: when the vocabulary elements and grammatical structures of rural cultural landscapes are deconstructed through diagrammatic methods, the rural cultural landscape primarily exhibits its material attributes. However, when lexical elements are constructed into compound sentences through grammatical rules, the immaterial attributes of the rural cultural landscape begin to emerge. Whether it be “Production and Living” scenes, “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship” scenes, “Important Festivals” scenes, or “Defense against External Enemies” scenes, these composite sentences encompass both human behavioral activities and the material spatial carriers that host these activities. This analogy resembles a living organism: when viewed individually, each bodily structure seems to lack consciousness; yet as a composite whole, it possesses the consciousness of life. This may well be an innovative aspect of this study.

In addition, this study combines the nested structure of spatial pattern language with the tree structure of diagrammatic language to construct a schematic diagram of the “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” nested structure of the Jiufanggou cultural landscape, intuitively reflecting the association paths and patterns of the “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” structure of the Jiufanggou village cultural landscape in different scenarios.

The isomorphy of rural cultural landscapes in this study shares similarities with the “triadic framework of spatial production” proposed by French sociologist Henri Lefebvre. Applying the triad theory to explain rural cultural landscapes allows us to interpret material environmental products such as cultural landscape vocabulary as “cultural landscape practices,” understand the social relationship experiences reflected in cultural landscape sentence as “representational cultural landscapes,” and interpret the cultural connotations and conceptualized imaginations embodied in cultural landscape semantic and context as “representations of cultural landscapes.” Traditional village cultural landscapes are rooted in the natural characteristics of the site while also encompassing lived experiences and historical transformations. They are dynamic, continuously evolving landscapes with numerous “representations”, generating diverse landscape meanings, and forming a text system, imagery system, and ritual system with profound connotations [41].

5. Conclusions

The local protection of rural cultural landscapes has long faced challenges such as “fragmentation” and “homogenization”. The introduction of a linguistic theoretical framework provides new methodological approaches and pathways for exploring the protection of rural cultural landscapes. This research paradigm first identifies and extracts elements of rural cultural landscapes, then deconstructs and translates them into spatial unit vocabulary. At the grammatical structure level, these spatial unit vocabulary are nested and combined according to specific constitutive rules, forming spatial sentences based on events/scenes with an intrinsic logical order. Ultimately, under the interactive influence of diverse semantic contexts and contextual rules, a complete and complex rural cultural landscape language system is constructed.

This study employs the rural cultural landscape language system as an analytical tool to conduct a systematic deconstruction and in-depth analysis of the cultural landscape pattern of Jiufanggou Village in Dawu County, Hubei Province. The research distills eight core landscape terms: “Mountain and Water Systems”, “Transportation Networks”, “Settlement Spaces”, “Street and Alley Spaces”, “Field dam space”, “Farmland Landscapes”, “Structures and Buildings”, and “Landscape Details”. These vocabulary terms collectively form landscape sentences based on four typical scenarios: “Production and Living”, “Sacrifice and Ancestor Worship”, “Important Festivals”, and “Defense against External Enemies”. The study then analyzed the landscape grammatical structures of different scenarios from four dimensions: “Scale”, “Hierarchy”, “spatial–temporal sequences”, and “Ornamentation”. Finally, the study explored the underlying semantic meanings and contextual rules of Jiufanggou Village’s cultural landscape from perspectives such as “Local Customs and Folkways”, “Traditional Culture”, “Ethics and Morality”, “Value Orientation”, and “Clan Rituals”.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. Our analysis revealed that the “vocabulary–grammar–sentence” nested structure could clearly reflect the relationships among the three components, but it fails to intuitively capture the more complex semantic and contextual aspects of the linguistic system within rural cultural landscapes. As a result, there are limitations in deeply exploring the isomorphism between the material and immaterial aspects of rural cultural landscapes. In the future, it may be worthwhile to explore the use of Lefebvre’s “triadic theory of spatial production” to elucidate the interactive relationships among the material environment, social cognition, and lived practices within cultural landscapes.

Additionally, the focus on a single village, Jiufanggou Village, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should test and validate these approaches in diverse cultural and geographical settings. Moreover, the reliance on qualitative data introduces subjectivity, which can be mitigated by incorporating more quantitative data in future studies.

Overall, the construction of a nested linguistic system for rural cultural landscapes is not only about analyzing spatial forms but more importantly about exploring the underlying logical order and traditional wisdom behind spatial creation, thereby achieving the goals of associative protection, the inheritance of diverse cultures, and sustaining the vitality of rural cultural landscapes.

At present, a considerable number of scholars and policymakers have reached a consensus: spatial narrative strategies for rural cultural landscapes can effectively address numerous existing issues in their presentation, such as the lack of regional cultural identity, insufficient vitality, difficulties in showcasing diversity and complexity, and challenges in interpretation [42]. As a method of expression that combines isomorphic events and spaces into a spatial–temporal composite [43], the spatial narrative establishes a strong mapping relationship with the rural landscape language system constructed in this study.

Consequently, the findings of this study not only deepen public understanding of the connotations and value of rural cultural landscapes but also offer valuable insights for researchers specializing in rural cultural landscape conservation, intangible cultural heritage preservation and transmission, and rural tourism development, as well as for policymakers engaged in these fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; methodology, Y.Z. and R.L.; formal analysis, R.L.; investigation, R.L. and W.L.; data curation, R.L. and C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and R.L.; writing—review and editing, R.L. and C.W.; visualization, R.L. and C.W.; supervision, W.L. and X.X.; project administration, Y.Z. and X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number: 52178054].

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest in this work. We have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | In traditional Chinese residential architecture, the main hall typically occupies the central axis of the building, with its spatial dimensions significantly larger than those of the side rooms. Structurally, it features heavier brick-and-stone foundations, denser brick walls, and higher-grade gabled roofs, with more intricate door and window decorations; Side rooms, as auxiliary spaces, are distributed on either side of the main hall. They are typically single-story or low-rise two-story structures with smaller spatial dimensions in terms of width and depth. They often use lightweight materials for foundations and walls, and their roof forms are predominantly gabled or hipped roofs. The overall architectural grade and decorative details of side rooms are subordinate to those of the main hall, establishing a clear hierarchical spatial order. |

| 2 | The threshing floor is a unique ritual space in Jiufanggou Village. During the Qingming Festival, villagers set up offerings here and worship facing the western side of Zhaiji Mountain (the direction in which their ancestors migrated), expressing their remembrance and respect for their ancestors’ migration journey. |

References

- Wang, Y.C.; Shen, J.K. Exploration of Multi-scale Spatial Process in the Characteristics and Evolution of Rural Landscape Pattern: A Case Study of Wuzhen. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kizos, T.; Primdahl, J.; Kristensen, L.S.; Busck, A.G. Introduction: Landscape Change and Rural Development. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Liu, B.G. Analysis of Rural Landscape Space in Heluo Town, Gongyi City from the Perspective of Schema Language. Landsc. Archit. Acad. J. 2024, 41, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, M.E.; Kaya, H.S.; Terzi, F.; Tolunay, D.; Alkay, E.; Balçık, F.B.; Tozluoğlu, E.G.; Yakut, S. The landscape identity of rural settlements: Turkey’s Aegean Region. Urbani Izziv 2024, 35, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.F.; Huang, H.L. On the Significance, Classification, Evaluation and Protection Design of Rural Cultural Landscape. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zakariya, K.; Ibrahim, P.H.; Wahab, N.A.A. Conceptual Framework of Rural. Landscape Character Assessment to Guide Tourism Development in Rural Areas. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 24, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górka, A.; Niecikowski, K. Classification of Landscape Physiognomies in Rural Poland: The Case of the Municipality of Cekcyn. Urban. Plan. 2021, 6, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Jin, Q.M. Study on the Types of Rural Cultural Landscape and Its Evolution. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. 1999, 22, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.F.; Tang, X.L.; Liu, S.Y. The Actual Situation and Path of Rural Cultural Landscape Protection: Environmental Education Path Based on “Human-Land Relationship”. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2020, 20, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C. Landscape Ecological Design and Eco-design Language. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 27, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Angel, S. Architectural Pattern Language; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C. The Logical Thinking and Framework of Landscape Space Pattern Language. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 24, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; Wang, M. Landscape Pattern and Language Teaching: The Thoughts of Simon Bell and Anne Spirn on Landscape Architecture Education. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 30, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Distilling and Building Chinese Environmental Pattern Language. Landsc. Archit. 2008, 15, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.Y. Pattern Language Expression of Landscape Based on the Graphics. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 32, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.H. Analysis of the Inheritance Paths of Foreign Landscape Design Languages: A Case Study of Japan, France, and the United States. Mod. Urban Res. 2024, 9, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Rong, X.; Chen, X.G. Study on Landscape Culture and Cultural Landscape. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2012, 40, 1618–1620+1774. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.H.; Zhang, T.; Lei, R.L. Retrospect and Expectation of Landscape Geography. World Reg. Stud. 2007, 16, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, X.; Yang, Z.H.; Wang, C.; Su, H.J.; Zhang, M.M. Coupling and co-evolution of biological and cultural diversity in the karst area of southwest China: A case study of Pogang Nature Reserve in Guizhou. Biodivers. Sci. 2020, 28, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.L. On Isomorphism in Model Epistemology. Stud. Dialectics Nat. 2021, 37, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.H. Research on modelling methods based on isomorphic ideas: From the perspective of philosophy of science. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2009, 29, 548–550. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.K. Structural Identicalness between Sound and Meaning of Languages in Connection with Patterns of Human Cultures. J. Peking Univ. 1995, 32, 87–95+108+128. [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim, R. Art and Visual Perception; Sichuan People’s Publishing House: Chengdu, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.Y. Topological Relationships in Classical Chinese Gardens. Archit. J. 1988, 8, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Karpodini-Dimitriadi, E. Spirit of Rural Landscape: Culture, Memory & Messages. Available online: http://cultrural.prismanet.gr/themedia/File/Rural_landscapes_EKD_1[1].pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Saussure, F.D. Course of General Linguistics/Chinese Translation of World Academic Masterpieces Series; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Syntactic Structures; China Social Science Press: Beijing, China, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Anne, W.S. The Language of Landscape. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2017, 4, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.H. Traveler among Mountains and Streams: The Translation and Construction of Language of Landscape Architecture. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 32, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.J. Meanings of Landscape. Time Archit. 2002, 1, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.H.; Cheng, B.; Dou, Y.D. The analysis and restoration path of pattern language in traditional Dong villages in Xiangxi. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 828–850. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.Y. Modern Language Semiotics; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.B.; Gui, F.B.; Xu, Y.S. Silent Village: Study on the Traditional Village of Jiufanggou in Dawu County, Hubei Province. Huazhong Archit. 2017, 35, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wang, K.; Guo, S.Q.; Geng, M.Y. The application of schema language and planning in the ecological space of the cold rural landscape. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 11795–11802. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Y.D.; Li, P.P.; Li, B.H. Deconstruction of public space characteristics and restoration of landscapes in traditional villages from the perspective of pattern language: A case study of Pingtan Village. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. 2024, 58, 382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; He, Y.S.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, S.Y.; Hu, X.J. Research on Water Adaptive Space of Traditional Villages Based on Pattern Language: Taking Zhangguying Village as an example. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2022, 29, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H.; He, Y.; Xu, G.T. Spatial Analysis and Inheritance Path of Traditional Villages Based on Schematic Language: The Case of Chengfeng Village on the Coast of Southern Fujian Province. In Spatial Governance for High-Quality Development: Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Urban Planning in China, 9th ed.; China Society of Urban Planning; China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 406–417. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.Q. Research on Traditional Settlement Space in Southern Hunan Based on Pattern Language. Chongqing Archit. 2021, 20, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.H.; Kong, Y.H.; Liu, S.H. The Analysis of the Liju Map of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of the Schema Language: A Case Study on Yulian Village in Mingxi County, Fujian Province. New Archit. 2022, 6, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.H.; Xu, C.L.; Zheng, S.N.; Wang, S.; Dou, Y.D. Spatial layout characteristics of Ethnic Minority villages based on pattern language: A case study of Southern Dong Area in Xiangxi as an example. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 40, 1784–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.C.; Ding, Y.F. The Place Where the Soul Returns is the Original Hometown: The Connotation and Representation of Native Cultural Landscape of Traditional Villages Associated with Taiwan. J. Ocean. Univ. China 2023, 1, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Gao, S.H. Research on Narrative Strategies for Interpreting Rural Cultural Landscape Across Time and Space. Art Des. 2024, 2, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Cao, K. Space of Historical Narratives: Narrative Method In Historical City Preservation Planning. Planners 2013, 29, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).