Participatory Assessment of Cultural Landscape Ecosystem Services: A Basis for Sustainable Place-Based Branding in Coastal Territories

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To enhance the accessibility of data so that it can be utilized to assess social values and preferences in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [1];

- The promotion of local development through the development and transfer of technologies that spread the benefits of tourism throughout the territory to reduce seasonality and pressure on the coastline, as demanded by Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament, establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning [2];

- To preserve ecosystem services in the coastline, increasing synergies between tourism and various sectors of the Blue Economy [3], particularly those related to sustainable food systems and those not conventionally associated with the Blue Economy based on their geographical location, as is the case of the second coastal line.

2. Literature Review and Study Background

2.1. Ecosystem Services of Historical and Cultural Heritage

- Elements of living systems that enable activities promoting health, recuperation, or enjoyment through active or immersive interactions (CICES 3.1.1.1);

- Elements of living systems that enable education and training, including the importance of between and within species genetic diversity (CICES 3.2.1.2).

- Elements of living systems that enable activities promoting health, recuperation, or enjoyment through passive or observational interactions (CICES 3.1.1.2);

- Elements of living systems that are resonant in terms of culture or heritage (CICES 3.2.1.3);

- Elements of living systems that enable esthetic experiences (CICES 3.2.1.4);

- Elements of living systems that have symbolic meaning, capture the distinctiveness of settings, or their sense of place (CICES 3.4.1.1);

- Elements of living systems that have spiritual or religious meaning (CICES 3.4.1.2).

2.2. Cultural Landscape

2.3. Tourist–Cultural Routes

2.4. Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGISs) for Cultural Heritage Management and Cultural Ecosystem Services Assessment

2.5. Study Background

2.5.1. Base Cartography

2.5.2. Natural Environment

2.5.3. Cultural Heritage Data

3. Description of Case Study, Methodology and Objectives

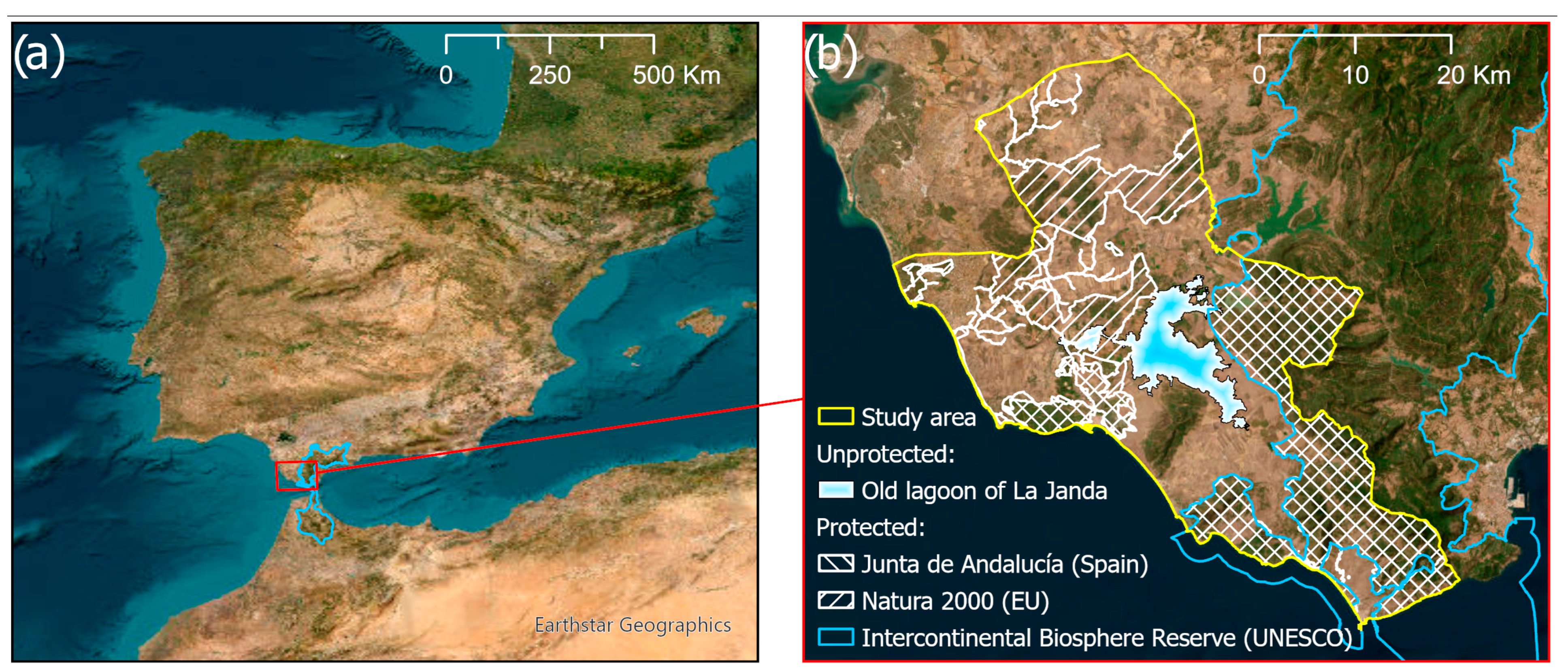

3.1. Description of Case Study

3.2. Methodology

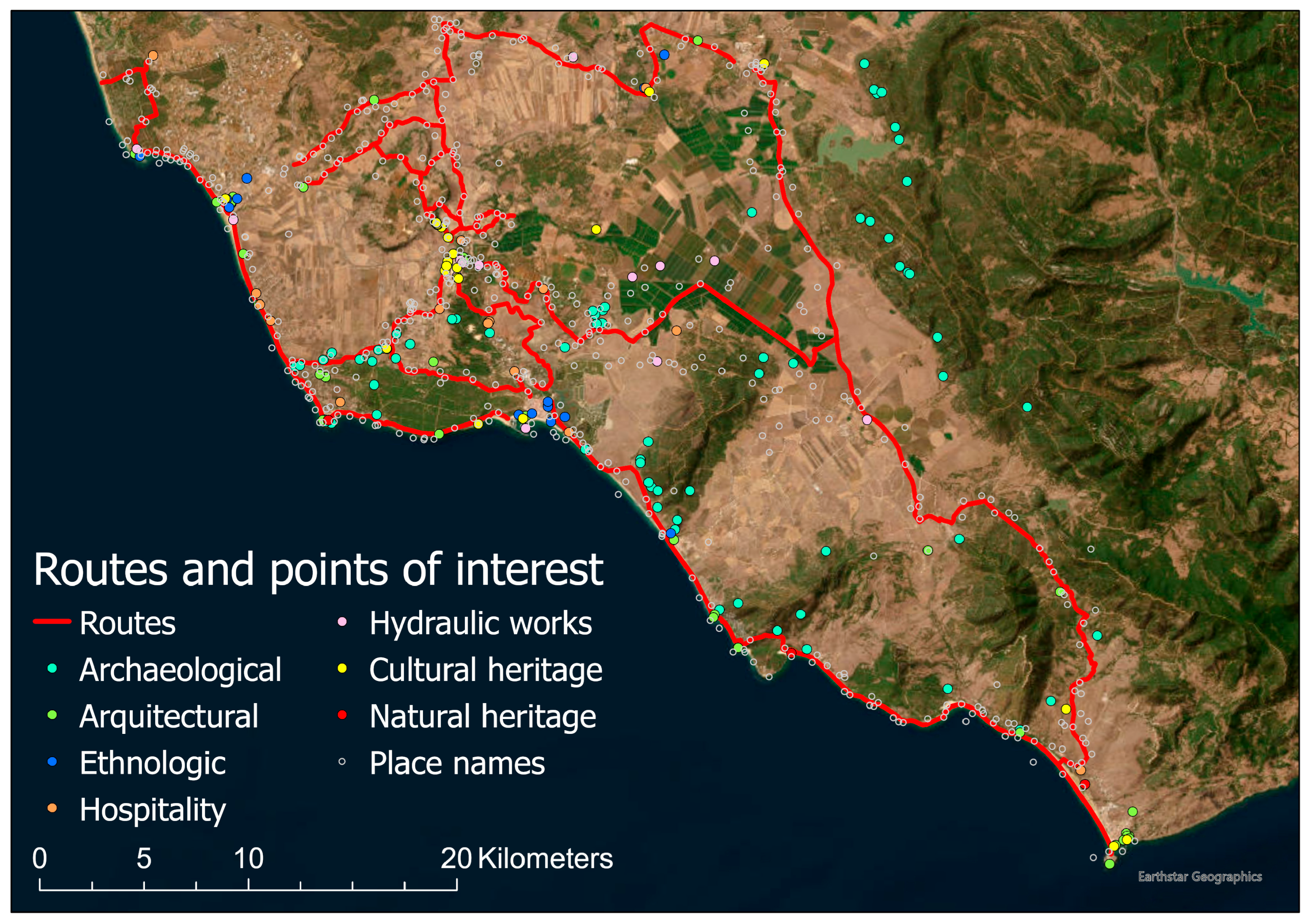

- Using ArcGIS Pro 3.4.0, the spatial information was compiled, comprising base cartography, cadastral cartography, and the specific location of cultural assets, including place names from official data sources listed in Section 2.5.

- The geolocated cultural information was filtered according to its intrinsic characteristics, and the selection of feasible routes was based on the cultural and natural interest of its surroundings. Those selected routes are connected to cover the study area as a whole.

- The information filter and the walkability of the network of routes by non-motorized means have been verified in situ through fieldwork. This was conducted to evaluate the connectivity of the public domains and to select the routes of greatest interest.

- The visual basin of the selected network of routes works as a filter to select points of cultural interest, which were documented by consulting the bibliography and drawing up an informative synthesis of their characteristics.

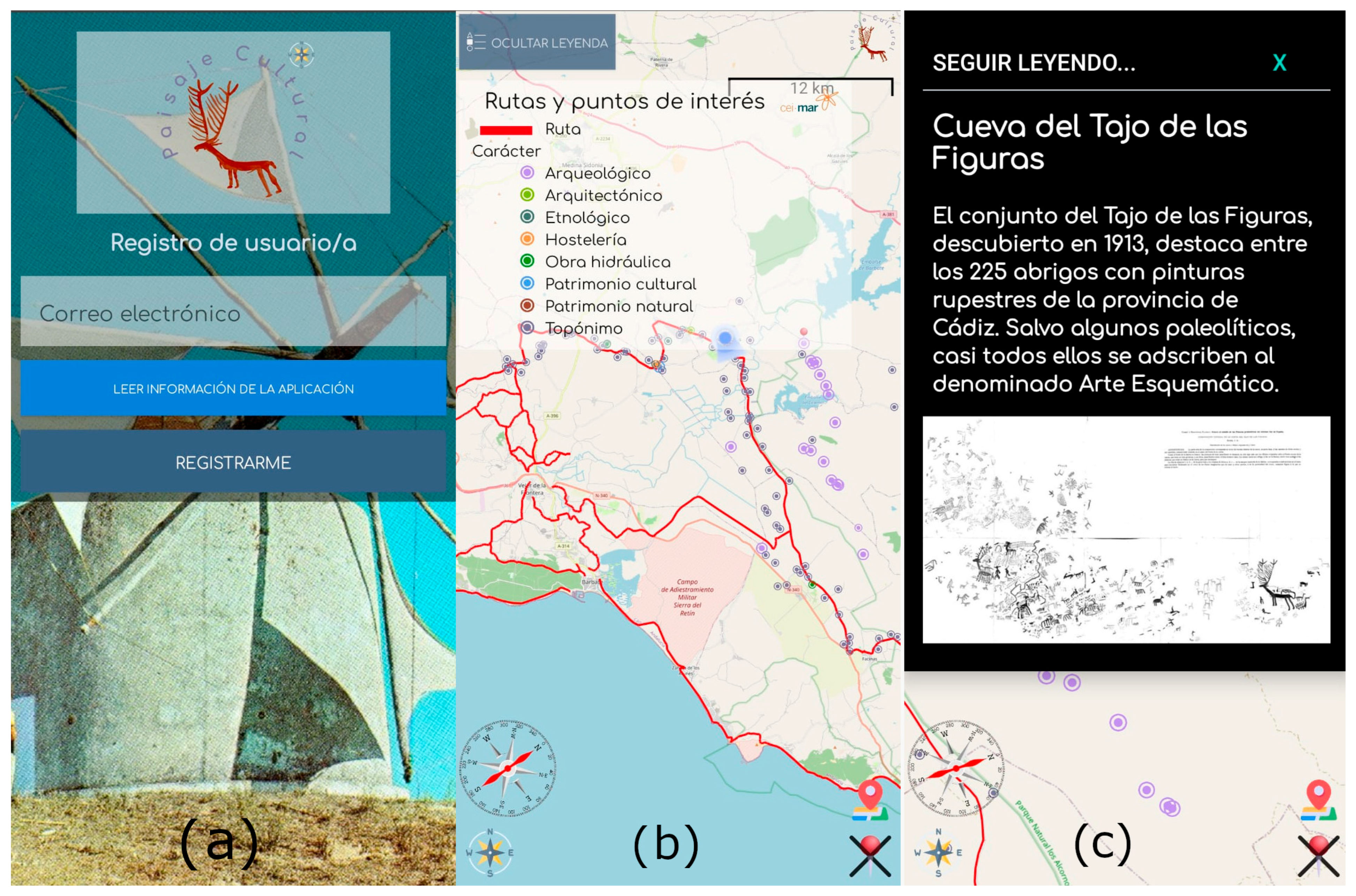

- With these routes and documented points, an application for mobile phones was created. This application allowed users to follow the routes on the ground and access information on each point as they approached it. The application has been distributed for the purpose of collecting data on its use and to quantify user interest in the various landmarks that have been proposed for consultation.

- This information has underpinned the spatial analysis of the cultural landscape of La Janda, which has finally resulted in synthesis cartography with which recommendations for sectoral management have been drawn up.

3.3. Objectives

- Evaluation of the visual basin perceptible from the routes that cross the public maritime–terrestrial domain and the public livestock trails.

- Georeferencing documentation on historical and cultural heritage, previously structured in a data model oriented towards its telematic dissemination.

- Developing a mobile phone application that gradually deploys information as the user moves around the territory.

- Collection of data on public preferences regarding the information offered, integrated into a PPGIS to obtain indicators on the CES of historical and cultural heritage.

4. Results

4.1. Synthesis of Information

4.2. New App Development

4.3. Data Analysis

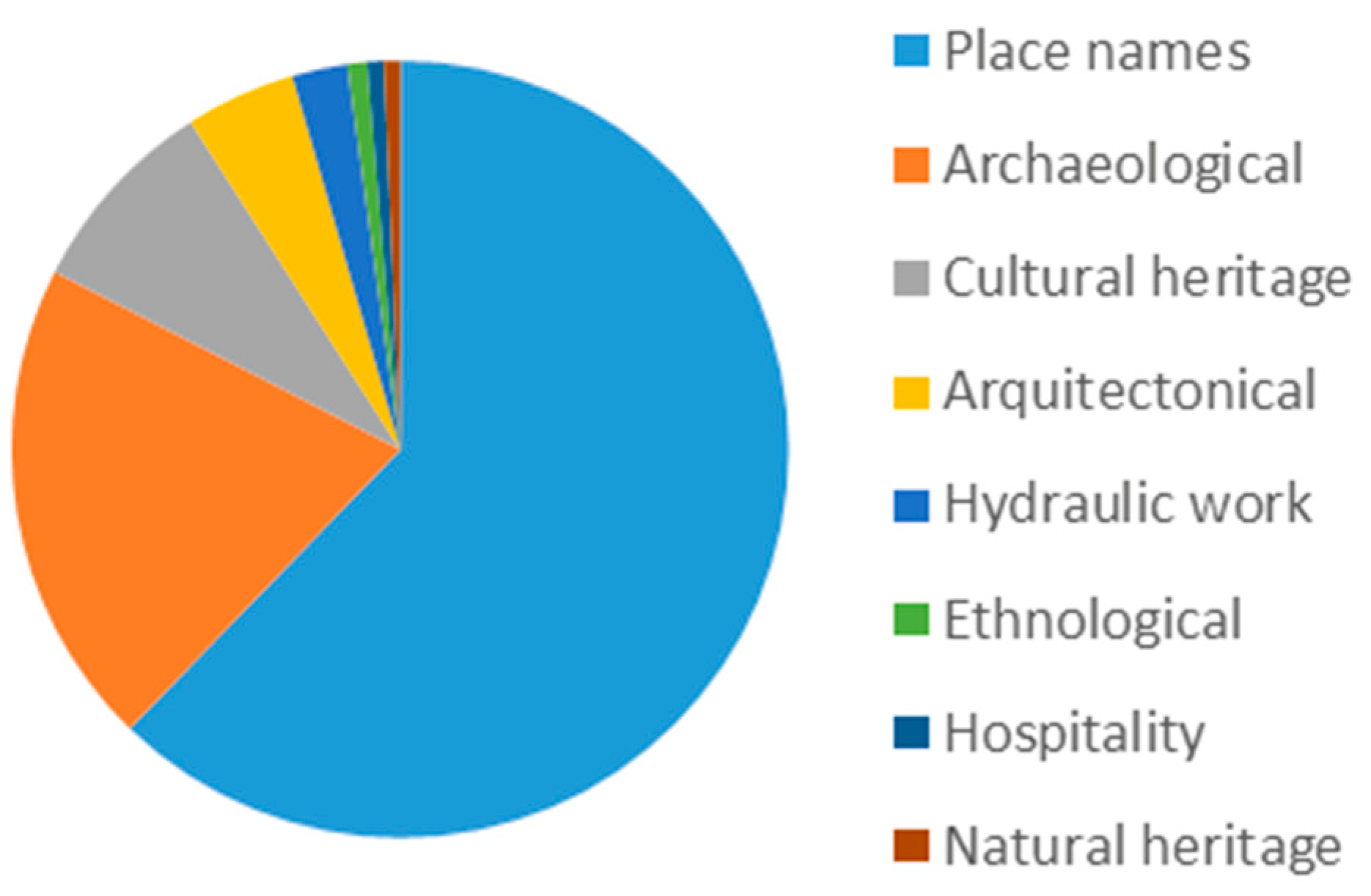

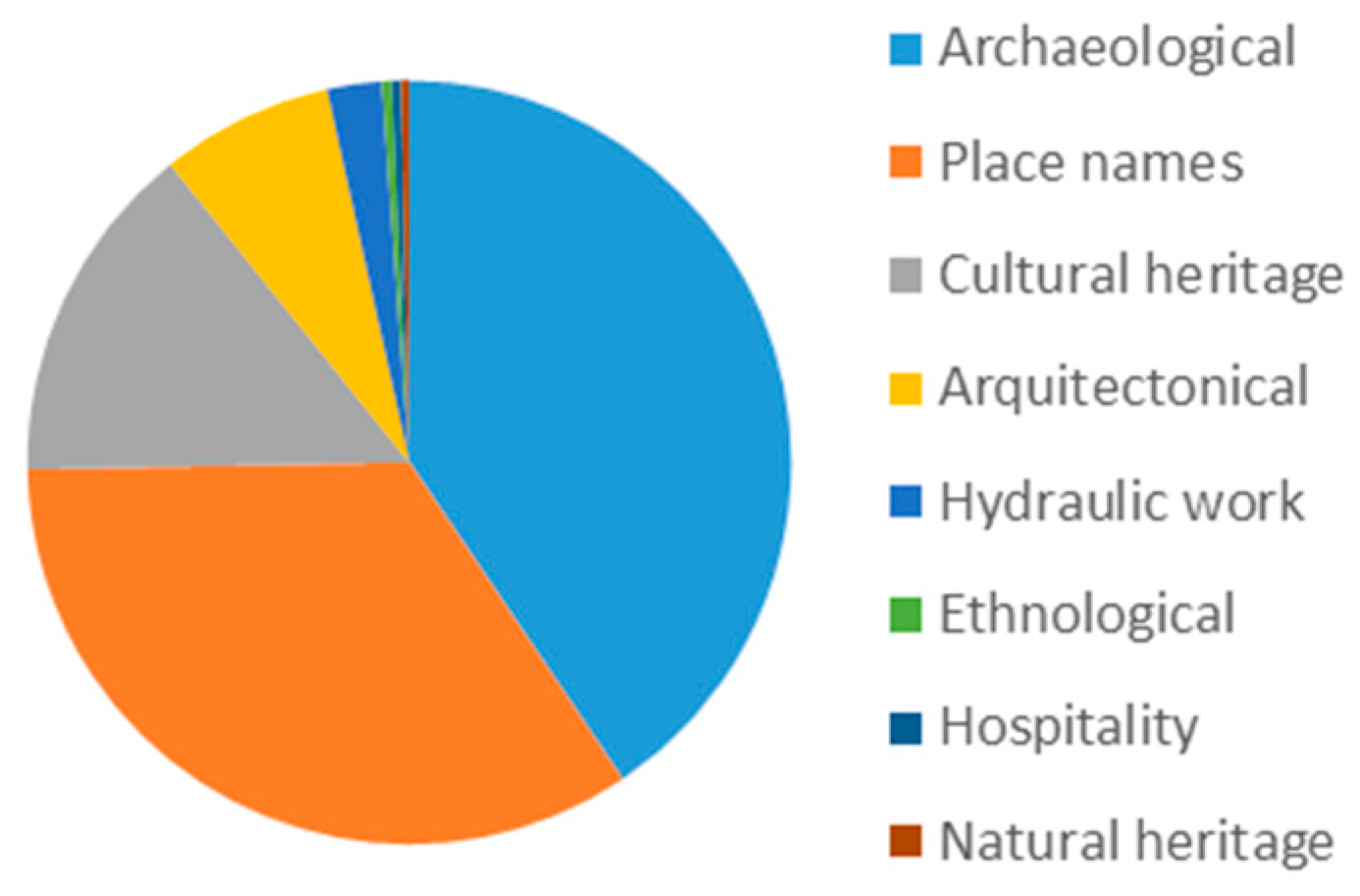

4.3.1. Points of Interest

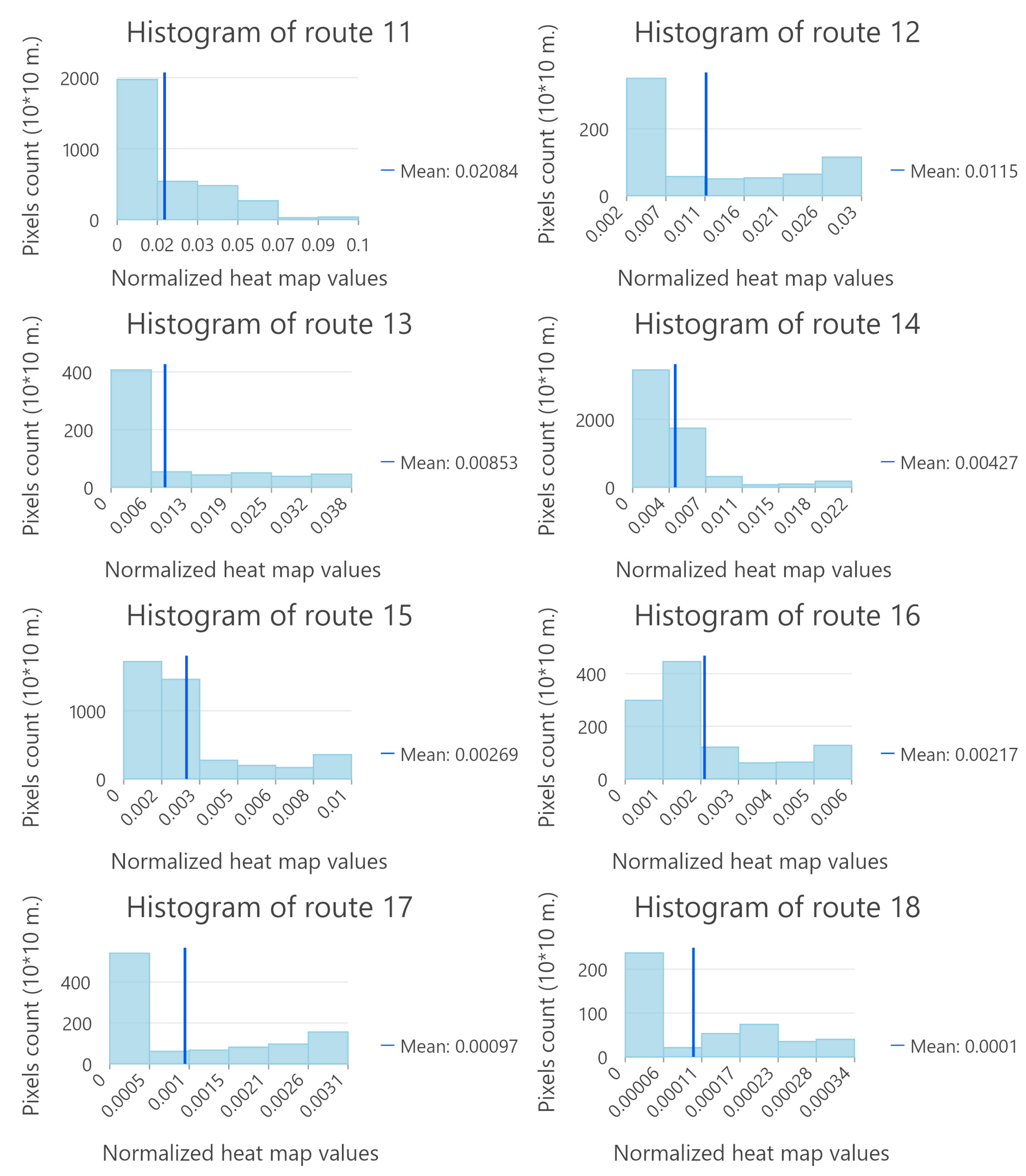

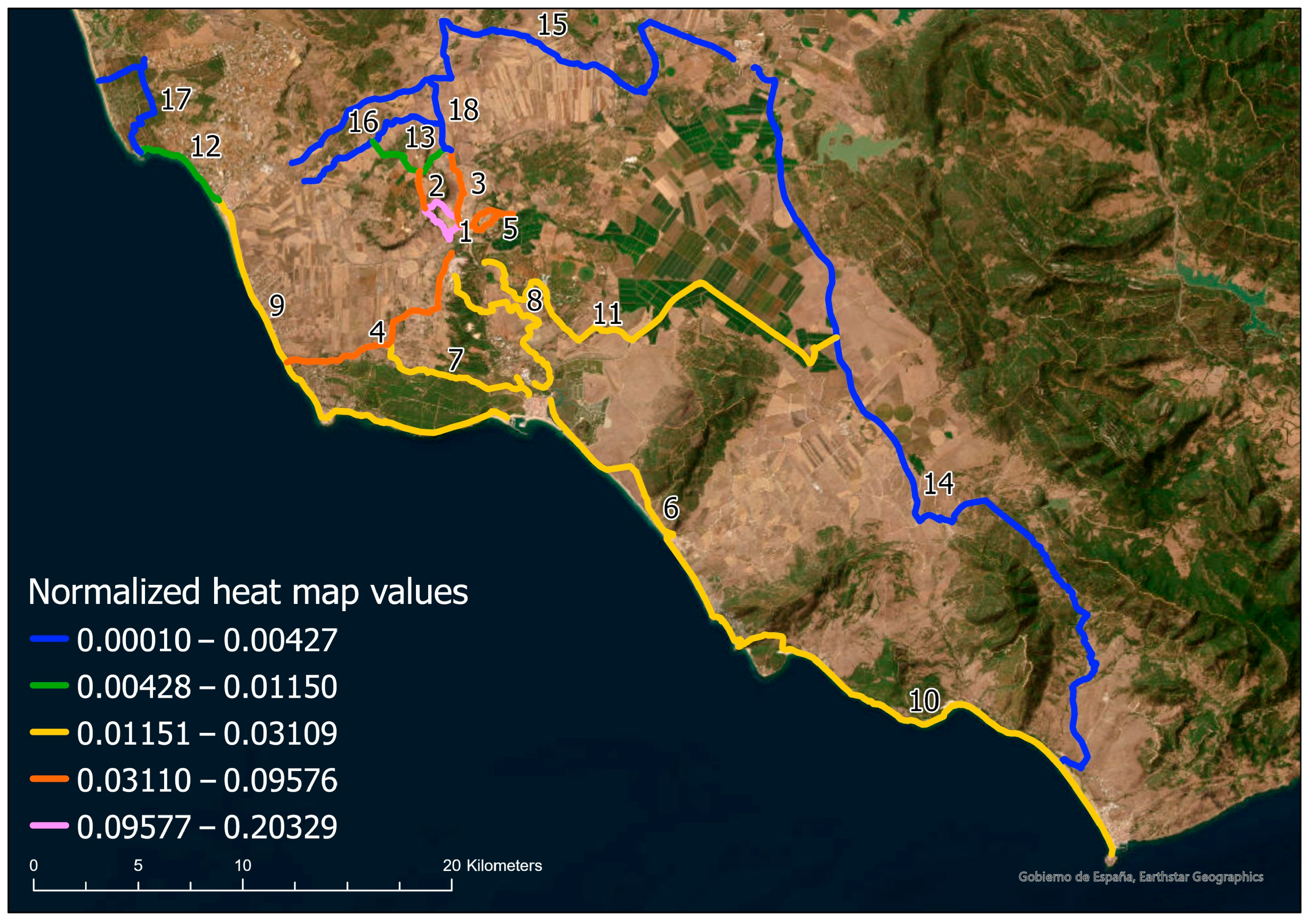

4.3.2. Routes of Interest

5. Discussion

5.1. Cultural Routes

5.2. Cultural Landmarks

5.3. Providing Information and Collecting Data

5.4. Recommendations

- The adjacency of heritage elements from disparate chronologies and characteristics discourages the promotion of homogeneous thematic routes. Instead, it is more advisable to consider most of the routes as examples of historical palimpsests.

- The heritage elements analyzed are in starkly divergent states of conservation. The range extends from those that are musealized and subject to access control, such as the Roman city of Baelo Claudia or the Castle and the lighthouse in the Las Palomas Island, in Tarifa, to those where access to the protected property is prohibited, as in the case of the 22 shelters and caves with cave paintings, among which those of the Tajo de las Figuras are particularly noteworthy.

- It is evident that these shortcomings hinder the possibilities of developing both cultural and nature tourism, the high potential of which is illustrated in the content of the cave paintings in the Tajo de las Figuras.

- The area continues to boast a rich and varied avian population, suggesting that the potential for ornithological tourism in the region remains significant. The Laguna de la Janda, a former site of ornithological significance, is well-positioned to support the development of this niche tourism sector, offering an ideal complement to the existing cultural tourism offerings. The adoption of an environmentally sustainable tourism model, characterized by its high added value, would contribute to the region’s economic development while ensuring the conservation of its natural heritage.

- The most unfavorable scenario pertains to the hermitage of San Ambrosio and numerous water mills in Santa Lucía, which are in a state of disrepair and dilapidation. In the latter case, the restoration and opening to the public of at least one of them, as well as some of the nine windmills, the 16 old coastal watchtowers, and the lighthouses of Roche, Trafalgar, Camarinal and Tarifa, is particularly recommendable.

- The archeological heritage of a region possesses the capacity to significantly influence the conceptualization of its identity and the vision for its future development. This potential derives from the ability of archeology to illuminate the region’s origins, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of its historical and cultural underpinnings.

- It is strongly advised that an archeological park be established in Cádiz, encompassing megalithic sites. This proposal is contingent upon the establishment of enclosures that would facilitate regulated access to the dolmen complexes of Aciscar, Almarchal, Breuil-Celemín, Caheruela-Caballero, Canchorrera, Charcones, Caño Arado, Facinas, Moraleja and Sierra Mariana.

- The Necropolis of Los Algarbes is a highly relevant archeological site, which is properly enclosed and available to the public upon request.

- The Tholos de Peñarroyo, which was recently the subject of an excavation, is located beneath the waters of the Celemin reservoir except during long drought periods. It is necessary that the tholos is relocated to a higher level to avoid damages and to allow visits, especially taking into account its singularity in a context where there are numerous dolmens, but there is no other tholos.

- The enhanced accessibility of protected assets makes a difference in the promotion of cultural tourism. The development of an application similar to the one that has been presented could facilitate the dissemination of crucial information regarding access conditions and visiting hours as well. Furthermore, the incorporation of augmented reality technology could serve to illustrate virtual reconstructions of the distinctive settlement characteristics of each historical period (e.g., Neolithic settlements, Roman villas), or significant historical events.

- It is unavoidable to acknowledge the inherent values of land uses, both natural and ethnological. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize the significance of fauna and livestock in these areas. The wetlands and watch points of the Strait of Gibraltar are of particular interest and should be given due consideration.

- It is estimated that seven species of cetacean pass through the Strait. Furthermore, the migratory passage between Europe and Africa brings together hundreds of thousands of birds belonging to more than 300 species twice a year.

- With regard to livestock, the Janda region is considered to be one of the most significant areas for the breeding of fighting cattle, and the Retinto cattle are also a long-standing part of the local landscape.

- The natural, agricultural, and livestock environment of the livestock trails should be appreciated in a sustainable and beneficial way to provide benefits for all. In order to mitigate the strong heat of the summer climate, it is essential that these areas are reforested.

- In a similar vein, to facilitate the movement of individuals through the Maritime Terrestrial Public Domain, the provision of shaded areas and drinking water supply beyond the hotel and catering facilities should be considered. These facilities should be located in the vicinity of the Eurovelo, a long-distance cycle lane recently constructed along the Cadiz coastline.

5.5. Ecosystem Services Valuation and Sustainable Development Goals

- SDG3: Ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages;

- SDG4: Quality education;

- SDG8: Promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment, and decent work for all;

- SDG9: Building resilient infrastructure, promoting sustainable industrialization, and fostering innovation;

- SDG11: Making cities more inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable;

- SDG14: Conserving and sustainably using oceans, seas, and marine resources;

- SDG15: Sustainably managing forests, combating desertification, halting and reversing land degradation, and halting biodiversity loss;

- SDG17: Revitalizing the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research Lines

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEI∙MAR | International Campus of excellence in Marine Sciences |

| CICES | Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services |

| ERDF | European Regional Development Fund |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| PAIDI | Andalusian Plan for Research, Development and Innovation |

| HUM | Humanities research group code |

| PPGIS | Public Participation Geographic Information Systems |

| UCA | University of Cádiz (Spain) |

Appendix A

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/index.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/89/oj/eng (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- OECD. Blue Economy. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/water-governance/blue-economy.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Daily, G.C. (Ed.) Introduction: What are ecosystem services. In Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M.J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, Y.E. An ecological perspective on the valuation of ecosystem services. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 120, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, S.C.; Costanza, R.; Wilson, M.A. Economic and ecological concepts for valuing ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity Ecological and Economic Foundations; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem service and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.; Brander, L.; Van der Ploeg, S.; Costanza, R.; Bernard, F.; Braat, L.; Christie, M.; Crossman, N.; Ghermandi, A.; Hein, L.; et al. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brink, P.; Rayment, M.; Bräuer, I.; Braat, L.; Bassi, S.; Chiabai, A.; Markandya, A.; Nunes, P.; ten Brink, B.; van Oorschot, M.; et al. Further Developing Assumptions on Monetary Valuation of Biodiversity Cost of Policy Inaction (COPI). European Commission Project—Final Report; Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP): London, UK; Brussels, Belgium, 2009; Available online: https://www.fondazionesvilupposostenibile.org/f/sharing/Monetary%20Valuation%20of%20Biodiversity_2009.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ludwig, D. Limitations of economic valuation of ecosystems. Ecosystems 2000, 3, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Managing without Prices: The Monetary Valuation of Biodiversity. Ambio 1997, 26, 546–550. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4314664 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Leff, E. Racionalidad Ambiental: La Reapropiación Social de la Naturaleza; Siglo XXI: México City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Settele, J. Precisely incorrect? Monetising the value of ecosystem services. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Polasky, S.; Goldstein, J.; Kareiva, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Pejchar, L.; Ricketts, T.H.; Salzman, J.; Shallenberger, R. Ecosystem services in decision making: Time to deliver. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. Cartography for the Evaluation of Ecosystem Services in Andalusia and Analysis of Indicators. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/88u/dataset/c2b463d0-c243-423e-855e-14a98c232974 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services. Available online: https://cices.eu/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Veidemane, K.; Reke, A.; Ruskule, A.; Vinogradovs, I. Assessment of Coastal Cultural Ecosystem Services and Well-Being for Integrating Stakeholder Values into Coastal Planning. Land 2024, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L.; Montagna, P.; Yoskowitz, D.; Scholz, D.; Tunnell, J. Stakeholder Perceptions of Coastal Habitat Ecosystem Services. Estuaries Coasts 2015, 38 (Suppl. 1), 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Gao, M. Coastal Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Bridge between the Natural Ecosystem and Social Ecosystem for Sustainable Development. Land 2024, 13, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drius, M.; Jones, L.; Marzialetti, F.; De Francesco, M.C.; Stanisci, A.; Carranza, M.L. Not just a sandy beach. The multi-service value of Mediterranean coastal dunes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, M. Introducción a la Arquitectura del Paisaje; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mollá Ruiz-Gómez, M. La creación de símbolos en los paisajes de Estados Unidos. In El Paisaje y sus Símbolos; Martínez de Pisón, E., Ortega Cantero, N., Eds.; Fundación Duques de Soria de Ciencia y Cultura Hispánica y Ediciones de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://fds.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/14-2016-El-paisaje-y-sus-simbolos-P.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Gómez Zotano, J.; Riesco Chueca, P. Marco Conceptual y Metodológico Para los Paisajes Españoles. Aplicación a tres Escalas Espaciales; Centro de Estudios Paisaje y Territorio, Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes: Sevilla, Spain, 2010; Available online: https://www.upv.es/contenidos/CAMUNISO/info/U0643729.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Roudié, P. El paisaje y los parajes del Patrimonio Mundial de la Humanidad de la UNESCO. In Paisaje y Ordenación del Territorio; Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transporte, Fundación Duques de Soria: Sevilla, Spain, 2002; Available online: http://www.paisajeyterritorio.es/assets/el-paisaje-y-los-parajes-del-patrimonio-mundial-de-la-humanidad-de-la-unesco.-roudie%2C-p2.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Council of Europe Landscape Convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Plan Nacional de Paisaje Cultural: Observatorio Español del Convenio del Paisaje del Consejo de Europa. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/planes-nacionales/planes-nacionales/paisaje-cultural.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Instituto Andaluz de Patrimonio Histórico. Guide to the Cultural Landscape of the Ensenada de Bolonia. Available online: https://repositorio.iaph.es/bitstream/11532/331255/1/Guia_del_Paisaje_Cultural_de_la_Ensenada.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Charter of Cultural Routes, ICOMOS 16th General Assembly. 2025. Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/culturalroutes_sp.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Calderón Puerta, D.M.; Ramírez Guerrero, G.; Arcila Garrido, M. Methodology for the evaluation of cultural tourism routes: A case applied to the cultural heritage of the province of Cádiz (Spain). J. Tour. Dev. 2023, 44, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, H. Las rutas culturales como patrimonio de la Humanidad. El caso de las fortificaciones americanas del Pacífico. Biblio 3W. Rev. Bibliográfica De Geogr. Y Cienc. Soc. 2005, X, 1–25. Available online: https://www.ub.edu/geocrit/b3w-562.htm (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Arcila Garrido, M.; López Sánchez, J.A.; Fernández Enríquez, A. Tourist-cultural routes and cultural itineraries as tourism products: Reflections on a methodology for their design and evaluation. In Spatial Analysis and Geographical Representation: Innovation and Application; De la Riva, J., Ibarra, P., Montorio, R., Rodrigues, M., Eds.; University of Zaragoza-AGE: Zaragoza, Spain, 2015; pp. 463–471. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283623753_Rutas_turisticos-culturales_e_itinerarios_culturales_como_productos_turisticos_reflexiones_sobre_una_metodologia_para_su_diseno_y_evaluacion (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- López Guzmán, T.J.; Lara de Vicente, F.; Merinero, R. Tourist routes as an engine of local development. The case of the “El Tempranillo” Route. Estud. Turísticos 2006, 137, 131–145. Available online: https://turismo.janium.net/janium/Objetos/REVISTAS_ESTUDIOS_TURISTICOS/96142.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Moreno Veloza, L.E.; Garzón Martínez, M.A. From hell to heaven in Boyacá: Heritage valuation of a road. Rev. De Antropol. Y Sociol. Virajes 2019, 21, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morère Molinero, N. On ICOMOS cultural itineraries and cultural tourism thematic routes. A reflection on their integration in tourism. J. Tour. Anal. 2012, 13, 57–68. Available online: https://analisis-turistico.aecit.org/index.php/AECIT/en/article/view/122 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Zamora Merchán, M. The use of GIS in Spanish archaeology: Approaches and approaches, twenty years later. Cuad. De Prehist. Y Arqueol. 2017, 2, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourteau, M.; Cerezo Andreo, F.; Arcila Garrido, M. GIS applied to the study of the maritime cultural landscape: Colonia del Sacramento from the 17th to the 20th century. Papeles Geogr. 2022, 67, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-del Río, R.; Tejedor-Cabrera, A.; Linares-Gómez, M. GIS-based applications for the design of cultural itineraries in landscapes with diffuse heritage values. The case of the Lower Guadalquivir territory (Archaeological Ensemble of Italica): Systematic review of scientific literature. In Proceedings of the III International Congress ISUF-H. Compact City vs. Diffuse City, Guadalajara, México, 19 September 2019; Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/144935 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Pedregal Mateos, B.; Segura Calero, S. Territory and post-normal science. In Territory and States. Elementos Para la Coordinación de las Políticas de Ordenación del Territorio en el Siglo XXI; Farinós, J., Peiró, E., Eds.; Tirant Humanities: Valencia, Spain, 2018; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdani, J.; Mitri, E. A Bibliography on the Application of GIS in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. GROMA Doc. Archaeol. 2017, 2. Available online: https://archaeopresspublishing.com/ojs/index.php/groma/article/view/1327 (accessed on 25 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Lopes, P. Achieving the state of research pertaining to GIS applications for cultural heritage by a systematic literature review. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, XLII-4, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Bibliometric analysis of GIS applications in heritage studies based on Web of Science from 1994 to 2023. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Fagerholm, N. Empirical PPGIS/PGIS mapping of ecosystem services: A review and evaluation. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 13, 119–133. Available online: https://participatorymapping.org/wp-content/publications/brown_fagerholm_review_final.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, C.; Xu, W.; Yingning, S.; Fengliang, T. Emerging trends in GIS application on cultural heritage conservation: A review. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying CES at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengberg, A.; Fredholm, S.; Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Saltzman, K.; Wetterberg, O. CES provided by landscapes: Assessment of heritage values and identity. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/ieca.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Datos Espaciales de Referencia de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/dega/datos-espaciales-de-referencia-de-andalucia-dera (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Nomenclátor del Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Available online: https://www.ign.es/web/rcc-nomenclator-nacional (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico. Available online: https://guiadigital.iaph.es/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Sede Electrónica del Catastro. Available online: https://www.sedecatastro.gob.es/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Dueñas López, M.Á.; Recio Espejo, J.M. Ecological Bases for the Restoration of the Wetlands of La JANDA (Cádiz, Spain); University of Cordoba Publications Service: Cordoba, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Del Espino Hidalgo, B.; Rodríguez Díaz, V.; González-Campos Baeza, Y.; Santana Falcón, I. Indicadores de accesibilidad para la evaluación del patrimonio cultural como recurso de desarrollo en áreas rurales de Huelva. ACE Archit. City Environ. 2022, 17, 11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shen, J. Landscape Sensitivity Assessment of Historic Districts Using a GIS-Based Method: A Case Study of Beishan Street in Hangzhou, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalusian Regional Government. Decree 155/1998, of July 21, approving the Livestock Trail Regulations of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. Official Gazette of the Andalusian Regional Government, No. 87, of 4 August 1998. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/1998/87/4 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- REDIAM (Red de Información Ambiental de Andalucía). Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/acceso-rediam (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Itinerarios Culturales: Planes de Manejo y Turismo Sustentable; López Morales, F.J., Vidargas, F., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: México City, México, 2011; Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1032/1/Itinerarios_Culturales_(2011).pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Navalón García, R. Escenarios, Imaginarios y Gestión del Patrimonio; Unic Autónoma Metropolitana—Xochimilco (Mexico) and University of Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2014; pp. 207–217. Available online: https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/escenarios-imaginarios-y-gestion-del-patrimonio-vol-1/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Vilà Bonilla, M. Diseño de Rutas; Universitat Oberta de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://openaccess.uoc.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/a553059c-4cb8-4a06-b568-1a17c2860023/content (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Dimitrovski, D.; Lemmetyinen, A.; Nieminen, L.; Pohjola, T. Understanding coastal and marine tourism sustainability—A multi-stakeholder analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafi, M.; Flannery, W.; Murtagh, B. Coastal tourism, market segmentation and contested landscapes. Mar. Policy 2020, 121, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Guerrero, G.; Fernández-Enríquez, A.; Arcila-Garrido, M.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A. Blue Marketing: New Perspectives for the Responsible Tourism Development of Coastal Natural Environments. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoff Bailey, Time perspectives, palimpsests and the archaeology of time. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2007, 26, 198–223. [CrossRef]

- Carrero-Pazos, M. Computational Archaeology of Territory. Methods and Techniques to Study Human Decisions in Past Landscapes; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.archaeopress.com/Archaeopress/Products/9781803276328 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Lazarich, M.; Ramos-Gil, A. Birds in rock art from hunter-gatherers and the first agro-pastoral communities in the Iberian Peninsula. In Raptor on the Fist—Falconry, its Imagery and Similar Motifs Throughout the Millennia on a Global Scale. Advanced Studies on the Archaeology and History of Hunting, vol. 2.1. Advanced Studies in Ancient Iconography II; Grimm, O., Ed.; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, NYUAD/New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 179–200. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344876866 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ramírez Aranda, N.; De Waegemaeker, J.; Van de Weghe, N. The evolution of public participation GIS (PPGIS) barriers in spatial planning practice. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 155, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Larrain, A.; McCall, M. Herramientas y actividades de mapeo participativo para estudios de arqueología de paisaje. In Geografía y Ambiente Desde lo Local; Vieyra, A., Urquijo, P., Eds.; UNAM—CIGA: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019; pp. 273–300. [Google Scholar]

- Basupi, L.V.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J. Using participatory mapping and a participatory geographic information system in pastoral land use investigation: Impacts of rangeland policy in Botswana. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzurro, A.E.; Cerri, J. Participatory mapping of invasive species: A demonstration in a coastal lagoon. Mar. Policy 2021, 126, 104412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.J.; Wiber, M.G.; Rooney, M.P.; Curtis Maillet, D.G. The role of public participation GIS (PPGIS) and fishermen’s perceptions of risk in marine debris mitigation in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2016, 133, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Strickland-Munro, J.; Kobryn, H.; Moore, S.A. Mixed methods participatory GIS: An evaluation of the validity of qualitative and quantitative mapping methods. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 79, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpilo, S.; Nyberg, E.; Vierikko, K.; Nieminen, H.; Arciniegas, G.; Raymond, C.M. Developing a Multi-sensory Public Participation GIS (MSPPGIS) method for integrating landscape values and soundscapes of urban green infrastructure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 230, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, R.A.; Sijtsma, F.J. A portfolio of natural places: Using a participatory GIS tool to compare the appreciation and use of green spaces inside and outside urban areas by urban residents. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laatikainen, T.; Tenkanen, H.; Kyttä, M.; Toivonen, T. Comparing conventional and PPGIS approaches in measuring equality of access to urban aquatic environments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 144, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Kronenberg, J. Eliciting non-monetary values of formal and informal urban green spaces using public participation GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Weber, D.; de Bie, K. Assessing the value of public lands using public participation GIS (PPGIS) and social landscape metrics. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 53, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerholm, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.M.; Torralba, M.; Moreno, G.; Plieninger, T. Assessing linkages between ecosystem services, land-use and well-being in an agroforestry landscape using public participation GIS. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 74, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, B.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Garcia Llorente, M.; Montes, C. Trade-Offs across Value-Domains in Ecosystem Services Assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 37, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, R.M.; Egoh, B.; Knight, A.T.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Reyers, B.; Rouget, M.; Roux, D.J.; Welz, A.; Wilhelm-Rechman, A. An operational model for mainstreaming ecosystem services for implementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 9483–9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondízio, E.S.; Gatzweiler, F.W.; Zografos, C.; Kumar, M.; Jianchu, X.; McNeely, J.; Martinez-Alier, J. Socio-cultural context of ecosystem and biodiversity valuation. In The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity Ecological and Economic Foundations; Kumar, P., Ed.; Earthscan Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268216759_Socio-cultural_context_of_ecosystem_and_biodiversity_valuation (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Czembrowski, P.; Kronenberg, J.; Czepkiewicz, M. Integrating non-monetary and monetary valuation methods—SoftGIS and hedonic pricing. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmus, M.; Renner, I.; Ulrich, S. Integración de los Servicios Ecosistémicos en la Planificación del Desarrollo: Un Enfoque Sistemático en Pasos Para Profesionales en TEEB; GIZ: Quito, Ecuador, 2013; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 25 August 2025).

| Protection Status | Hectares | Study Área (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional government protection | Natural Park, Natural Reservation, Natural Monument, and Others | 42,477 | 29.05% |

| European Union protection | Special Conservation Zones | 61,287 | 41.91% |

| Special Protection Areas for Birds | 40,602 | 27.77% | |

| UNESCO protection | Intercontinental Biosphere Reservation of the Mediterranean | 36,696 | 25.09% |

| Old lagoon of La Janda | Unprotected | 8531 | 5.83% |

| Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Administrative unit | 74 |

| Building | 169 |

| Hydrography | 610 |

| Land cover | 1200 |

| Land form | 653 |

| Other | 37 |

| Populated places | 831 |

| Protected site | 837 |

| Transport network | 391 |

| Transport Network Type | Count | Legal Width (m.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path | 113 | Not applicable | |

| Lane | 28 | Not applicable | |

| Public domain of livestock trails | Cañadas | 50 | 75 |

| Cordeles | 7 | 37.5 | |

| Padrones | 20 | 30–31 1 | |

| Veredas | 42 | 20 | |

| Coladas | 68 | 7–17 1 | |

| Tag | Elements | Category | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Trafalgar Cape | Natural/archeological/ Architectural heritage | Good |

| B | Hermitage of San Ambrosio | Archeological | In ruins, not open to the public |

| C | Windmills of Vejer | Cultural heritage | Good, not open to the public |

| D | Watermills of Santa Lucía | Cultural heritage | In ruins, not open to the public |

| E | Tajo de las Figuras | archeological | Good, not open to the public |

| F | Baelo Claudia | Archeological | Good, open to the public |

| G | Tarifa | Cultural heritage | Good, open to the public |

| Ranking | Name | Normalized Mean Heat Map Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Santa Lucía | 0.20328701 |

| 2 | Vereda de la Muela | 0.095764 |

| 3 | Vereda de Cano | 0.085285 |

| 4 | Vejer–Zahora | 0.084516 |

| 5 | Hijuela del Aberajuco | 0.0826 |

| 6 | Trafalgar–Punta Camarinal | 0.031094 |

| 7 | San Ambrosio–Barbate | 0.03087 |

| 8 | Vejer–Barbate | 0.02986 |

| 9 | Conil–Trafalgar | 0.02413 |

| 10 | Punta Camarinal–Tarifa | 0.02349 |

| 11 | Manzanete–Tapatana | 0.02084 |

| 12 | Muelle de Conil– Conil | 0.0115 |

| 13 | Camino del Arroyo y Camino del Cojo | 0.00852 |

| 14 | Benalup–Playa de Los Lances | 0.00427 |

| 15 | Conil–Benalup | 0.00269 |

| 16 | Camino de Conil a Casas Viejas | 0.00217 |

| 17 | Pista de Ávila–Muelle de Conil | 0.00097 |

| 18 | Vereda Misericordia | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Enríquez, A.; Ramírez-Guerrero, G.; De Andrés-García, M.; García-Onetti, J. Participatory Assessment of Cultural Landscape Ecosystem Services: A Basis for Sustainable Place-Based Branding in Coastal Territories. Land 2025, 14, 1868. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091868

Fernández-Enríquez A, Ramírez-Guerrero G, De Andrés-García M, García-Onetti J. Participatory Assessment of Cultural Landscape Ecosystem Services: A Basis for Sustainable Place-Based Branding in Coastal Territories. Land. 2025; 14(9):1868. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091868

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Enríquez, Alfredo, Gema Ramírez-Guerrero, María De Andrés-García, and Javier García-Onetti. 2025. "Participatory Assessment of Cultural Landscape Ecosystem Services: A Basis for Sustainable Place-Based Branding in Coastal Territories" Land 14, no. 9: 1868. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091868

APA StyleFernández-Enríquez, A., Ramírez-Guerrero, G., De Andrés-García, M., & García-Onetti, J. (2025). Participatory Assessment of Cultural Landscape Ecosystem Services: A Basis for Sustainable Place-Based Branding in Coastal Territories. Land, 14(9), 1868. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091868