Linking Walkable Urbanism and Hiking Tourism in a Mountainous Metropolitan City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional Narratives

2.2. Walkable Urbanism

2.3. Hiking Tourism

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Protocol

3.2. Data Sources and Analysis

3.2.1. Official Documents and Chronological Narrative

3.2.2. User-Generated Content and Corpus Analysis

4. Results

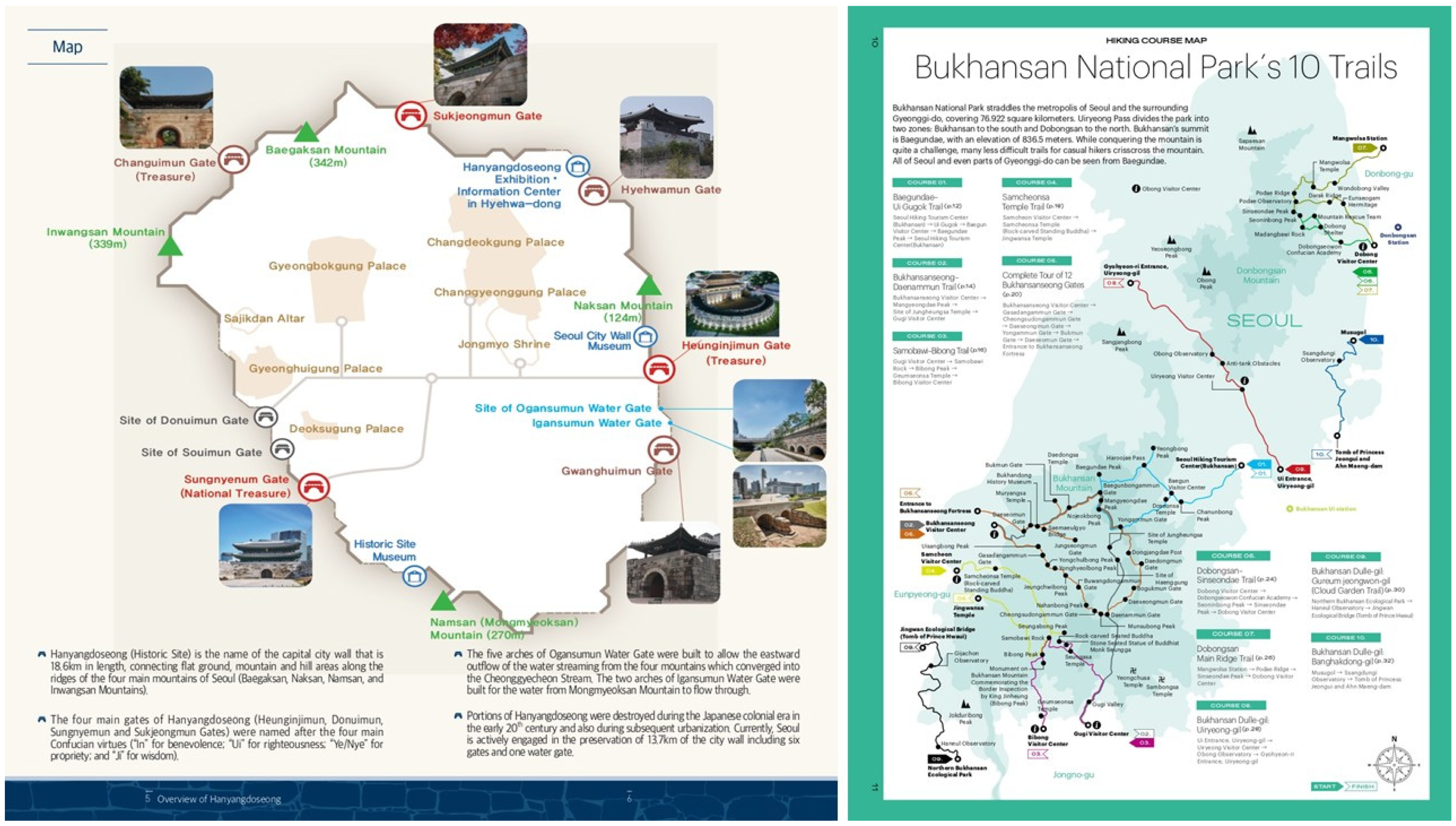

4.1. Walkable Urbanism and Urban Forest Recreation

4.2. Hiking Tourism Experiences

4.2.1. The 10 Most Preferred Hiking Routes

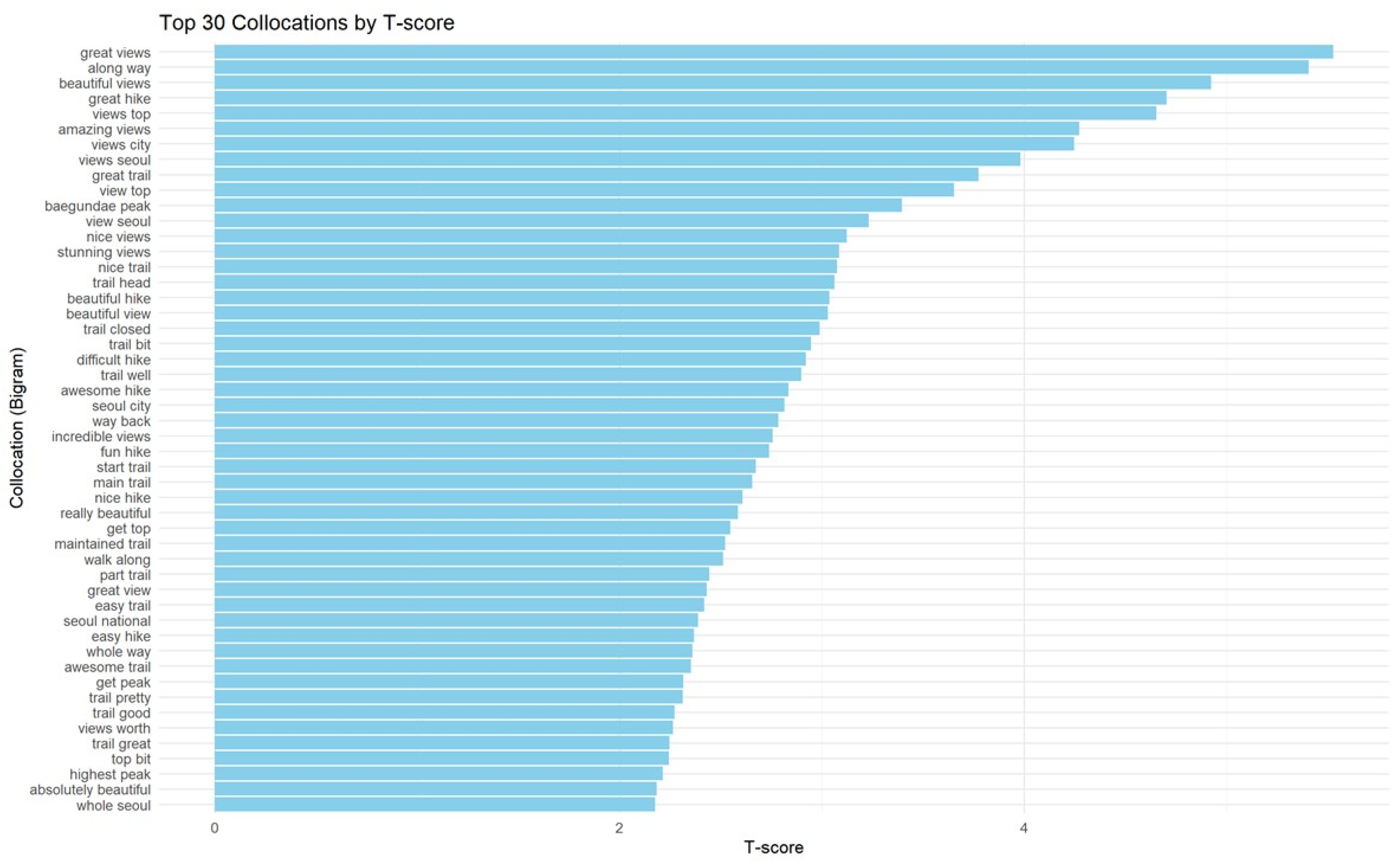

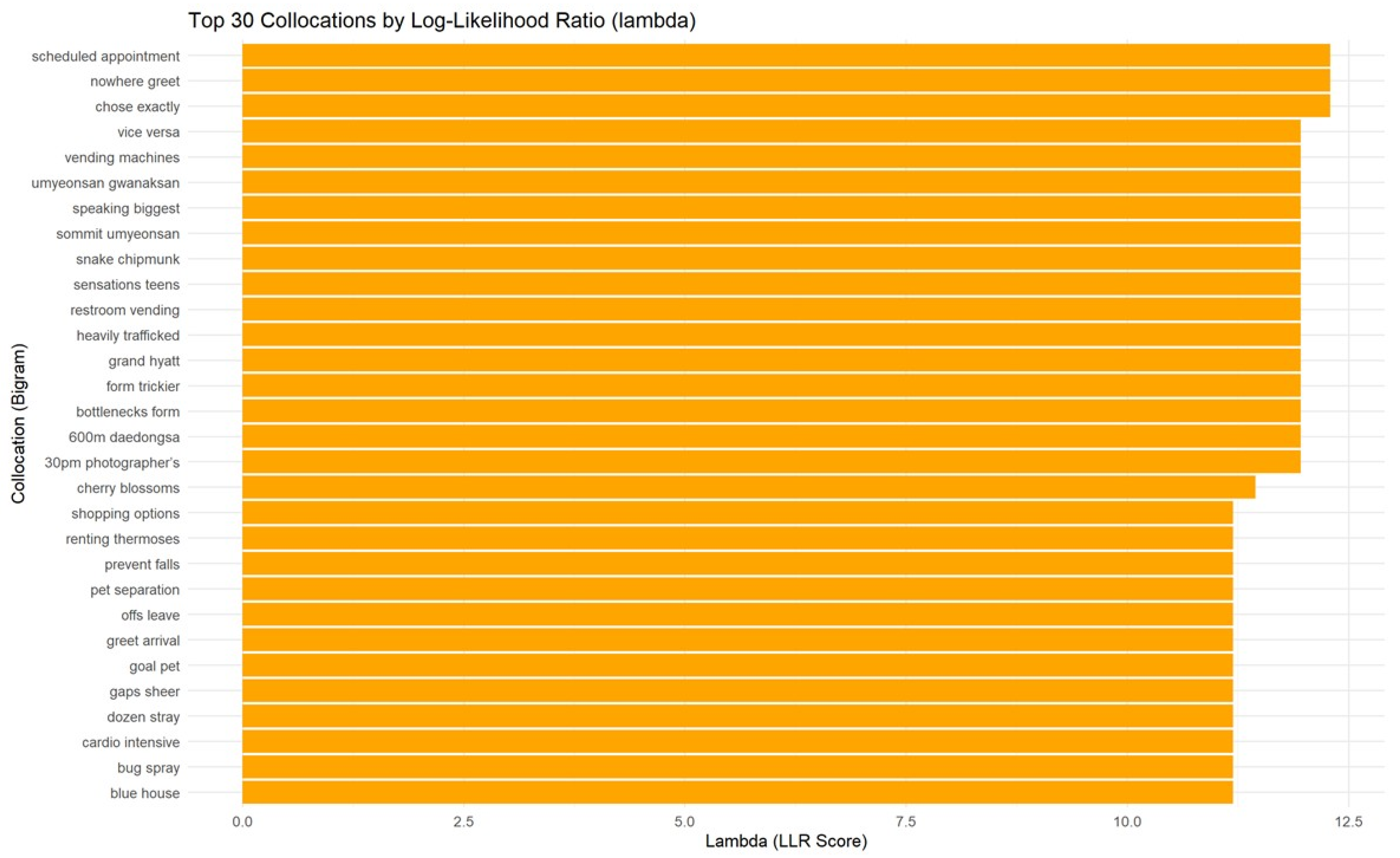

4.2.2. Word Collocation Analysis

4.3. Summary of Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 30 Most Common Collocated Terms | 30 Low-Frequency but Significant Collocations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

O: observed frequency, E: expected frequency | by lambda calculation using quentede.stats R package (version 4.5.1) | |||||

| collocation | lambda (λ) | z-score | T-score | collocation | lambda (λ) | z-score |

| great views | 3.085 | 15.222 | 5.527 | chose exactly | 12.297 | 5.940 |

| along way | 4.234 | 17.091 | 5.407 | nowhere greet | ||

| beautiful views | 3.017 | 13.586 | 4.923 | scheduled appointment | ||

| great hike | 2.457 | 11.455 | 4.703 | 30 pm photographer’s | 11.960 | 5.702 |

| views top | 2.556 | 11.726 | 4.652 | 600 m daedongsa | ||

| amazing views | 3.664 | 13.076 | 4.273 | bottlenecks form | ||

| views city | 3.422 | 12.732 | 4.246 | form trickier | ||

| views seoul | 2.740 | 10.638 | 3.982 | grand hyatt | ||

| great trail | 1.765 | 7.753 | 3.774 | heavily trafficked | ||

| view top | 2.827 | 10.076 | 3.655 | restroom vending | ||

| baegundae peak | 4.546 | 11.790 | 3.397 | sensations teens | ||

| view seoul | 3.065 | 9.626 | 3.232 | snake chipmunk | ||

| nice views | 2.177 | 7.348 | 3.124 | summit umyeonsan | ||

| stunning views | 4.635 | 9.594 | 3.085 | speaking biggest | ||

| nice trail | 1.679 | 6.255 | 3.075 | umyeonsan gwanaksan | ||

| trail head | 5.498 | 6.289 | 3.062 | vending machines | ||

| beautiful hike | 1.851 | 6.519 | 3.036 | vice versa | ||

| beautiful view | 2.649 | 8.174 | 3.029 | cherry blossom | 11.449 | 6.736 |

| trail closed | 2.681 | 7.563 | 2.988 | bug spray | 11.198 | 6.157 |

| trail bit | 1.945 | 6.441 | 2.945 | dozen stray | ||

| difficult hike | 2.376 | 7.240 | 2.921 | gaps sheer | ||

| trail well | 2.007 | 6.610 | 2.898 | goal pet | ||

| awesome hike | 3.387 | 8.313 | 2.836 | greet arrival | ||

| offs seoul city | 3.152 | 8.712 | 2.814 | offs leave | ||

| way back | 2.903 | 7.950 | 2.783 | prevent falls | ||

| incredible views | 4.557 | 8.671 | 2.757 | shopping options | ||

| fun hike | 2.831 | 7.521 | 2.739 | blue house | ||

| start trail | 2.127 | 6.138 | 2.672 | cardio intensive | ||

| main trail | 3.457 | 7.284 | 2.656 | pet separation | ||

| nice hike | 1.692 | 5.370 | 2.609 | renting thermoses | ||

References

- Du, C. On the mountain urban landscape studies. Sci. China Ser. E-Technol. Sci. 2009, 52, 2497–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; He, T.; Huang, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Y. Assessment of cultural ecosystem service values in mountainous urban parks based on sex differences. Land 2025, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Act on Urban Parks, Greenbelts, Etc.; Ministry of Government Legislation: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 1980. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Lee, S.; Chung, W.J.; Jeong, C. Exploring sentiment analysis and visitor satisfaction along urban liner trails: A case of the Seoul Trail, South Korea. Land 2024, 13, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Trail, S. 2.0. Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. Available online: http://gil.seoul.go.kr (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Seoul Tourism Organization. Seoul Hiking Tourism Center. 2022. Available online: https://seoulhiking.or.kr/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ostrom, E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.Y. Comparison of Development Process of Forest Recreation Policy in Korea, China and Japan. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. Available online: http://dcollection.snu.ac.kr/common/orgView/000000158131 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Korea Forest Service. Survey on National Awareness of Mountain Climbing and Forest Trail Experience. 2022. Available online: http://center.forest.go.kr/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Korea Forest Service. Survey on Public Awareness of Hiking and Trekking. 2021. Available online: https://www.forest.go.kr/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Korea Forest Service. Survey on Public Awareness of Forest Recreation Activities. 2022. Available online: http://www.forest.go.kr/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Kim, S.-I.; Jeong, C. Influence of perceived restorativeness on recovery experience and satisfaction with walking tourism: A multiple-group analysis of daily hassles and the types of walking tourist attractions. Land 2025, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoullo 7017 White Paper; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. Available online: https://ebook.seoul.go.kr/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project White Paper; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006. Available online: https://lib.seoul.go.kr/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Kim, L.; Jeong, C. Exploring pedestrian satisfaction and environmental consciousness in a railway-regenerated linear park. Land 2025, 14, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2030 Seoul Plan. 2013. Available online: https://www.seoulsolution.kr/en/content/1769 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Davis, V.O. Inclusive Transportation: A Manifesto for Repairing Divided Communities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Act on Urban Parks and Green Areas; Revised 2024; Ministry of Government Legislation: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2005. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Forest Welfare Promotion Act; Revised 2020; Ministry of Government Legislation: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2015. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Cultural Heritage Protection Act; Revised 2010; Ministry of Government Legislation: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 1962. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Mercadé-Aloy, J.; Cervera-Alonso-de-Medina, M. Enhancing access to urban hill parks: The Montjuïc trail masterplan and the 360° route design in Barcelona. Land 2024, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, W.; Danzeng, Z.; Mima, L.; Ma, R. The spatial mismatch between tourism resources and economic development in mountainous cities impacted by limited highway accessibility: A typical case study of Lhasa City, Tibet Autonomous Region, China. Land 2023, 12, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, L. A corpus-based study: Analysis of the positive reviews of Amazon.com users. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud 2019, 10, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysek-Pawlak, M.M.; Pabich, M. Walkability—The New Urbanism principle for urban regeneration. J. Urban Int. Res. Placemar. Urban Sustain. 2021, 14, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K.; Chipeniuk, R. Mountain tourism: Toward a conceptual framework. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, J. Bureaucracy and the imaginal realm: Max Weber, rationality and the substantive basis of public administration. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2022, 5, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, H.; Glückler, J. Institutional change in economic geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K. The relevance of neo-institutionalism for organizational change. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2284239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, M. Historical institutionalism and technological change: The case of Uber. Bus. Polit. 2021, 23, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raak, A.; Paulus, A. The emergence of multidisciplinary teams for interagency service delivery in Europe: Is historical institutionalism wrong? Health Care Anal. 2008, 16, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, J.C.; Garcia, M.A.; Putnam, L.L.; Mumby, D.K. Institutional theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Modesto, A.; Kamenečki, M.; Tomić Reljić, D. Application of suitability modeling in establishing a new bicycle–pedestrian path: The case of the abandoned Kanfanar–Rovinj railway in Istria. Land 2021, 10, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanshahi, G.; Soltani, A.; Roosta, M.; Askari, S. Walking as soft mobility: A multi-criteria GIS-based approach for prioritizing tourist routes. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1080–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayode, I.O.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E. Barriers affecting promotion of active transportation: A study on pedestrian and bicycle network connectivity in Melbourne’s west. Land 2025, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Lassaube, U.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. Mapping the implementation practices of the 15-minute city. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 2094–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Diab, E. Developing a 15-minute city policy? Understanding differences between policies and physical barriers. Transp. Res. A 2025, 191, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgante, B.; Patimisco, L.; Annunziata, A. Developing a 15-minute city: A comparative study of four Italian cities—Cagliari, Perugia. Cities 2024, 146, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, S.A.; Frimpong, L.K.; Oviedo, D.; Mensah, S.L.; Fianoo, I.N.; Nieto-Combariza, M.J.; Kita, M. Policy-reality gaps in Africa’s walking cities: Contextualizing institutional perspectives and residents’ lived experiences in Accra. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 47, 2381–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radics, M.; Christidis, P.; Alonso, B.; dell’Olio, L. The X-minute city: Analysing accessibility to essential daily destinations by active mobility in Seville. Land 2024, 13, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D. Development of transport planning in Seoul and South Korea: A historical overview from a SUMP perspective. Asian Transp. Stud. 2025, 11, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Li, C. Interplay between greenspace interactions and sense of place in Seoul city. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1343373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, J.; Gao, C.; Su, Z.; Bao, D.; Zhang, Z. Network-based transportation system analysis: A case study in a Mountain City. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2018, 107, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeyer, B.; Mpozagara, R.; Consales, J.N. Metropolitan mountains: Sainte-Victoire as a public park in Aix-Marseille Provence Metropolis, France? Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Zhao, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. Architectural design methods for mountainous environments. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 22, 2596–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Son, Y. Assessing and mapping cultural ecosystem services of an urban forest based on narratives from blog posts. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.C.; Park, M.S.; Youn, Y.C. Preferences of urban dwellers on urban forest recreational services in South Korea. Urban For. Urban Green 2013, 12, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, K.; Sers, S.; Buday, L.; Wäsche, H. Why hikers hike: An analysis of motives for hiking. J. Sport Tour. 2023, 27, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krevs, M.; Repe, B.; Mazej, M. Reconsidering the basics of mountain trail categorisation: Case study in Slovenia. Eur. J. Geogr. 2023, 14, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Mountain Tourism; UN World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2025. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/mountain-tourism (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Lee, J.; Lim, C.H.; Kim, G.S.; Markandya, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, W.K.; Son, Y. Economic viability of the national-scale forestation program: The case of success in the Republic of Korea. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodev, Y.; Zhiyanski, M.; Glushkova, M.; Shin, W.S. Forest welfare services—The missing link between forest policy and management in the EU. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.H. Transition from the vehicle-oriented city to the pedestrian-friendly city. In Seoul Solutions; The Seoul Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2015; Available online: https://www.seoulsolution.kr/en/node/6307 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Forestry Culture and Recreation Act; Ministry of Government Legislation: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2005. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Kim, G. History of Seoul’s Parks and Green Space Policies: Focusing on Policy Changes in Urban Development. Land 2022, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul Survey, 2024. 2023. Available online: http://data.seoul.go.kr (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Innovations that change citizens’ lives. In Seoul White Paper; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. Available online: https://seoulsolution.kr/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Kim, M. Study on Establishing a Master Plan to Promote Leisure Culture in Seoul’s Park and Forest. 2024. Available online: http://lib.seoul.go.kr (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Kim, W. Seoul Trail Management and Operation Plan. 2014. Available online: https://www.si.re.kr/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Korea Forest Service. Korea Forest Service Self-Evaluation Report. 2025. Available online: https://evaluation.go.kr/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Korea Forest Service. The Sixth National Forest Plan, 2018–2035. Available online: https://www.forest.go.kr/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Korea Forest Service. The Fifth National Forest Plan, 2008–2017. Available online: https://www.forest.go.kr/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Korea Forest Welfare Institute. Korea Forest Welfare Institute Sustainability Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.fowi.or.kr/sustainabilityReport/2021/2021%20FoWI%20Report%20(Eng).pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. The Fifth National Comprehensive Territorial Plan (2020–2040): Visions and Strategy for Korea’s Green Transition 2040. 2019. Available online: https://www.me.go.kr/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Choi, H.S.; Ahn, S.E.; Lee, W.S.; Song, S.G.; Lee, G.S. The Transformation of Urban Park and Green Space Policy for Sustainability; Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; Available online: https://www.kei.re.kr/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Gianfelici, C.; Martin-Sardesai, A.; Guthrie, J. Investigating the development of narratives in directors’ reports: An analysis of barilla over six decades. Acc. Audit. Acc. J. 2024, 37, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezina, V. Statistics in Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, S. Corpora and collocations. In Corpus Linguistics: An International Handbook; Lüdeling, A., Kytö, M., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 1212–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, K.; Watanabe, K.; Wang, H.; Nulty, P.; Obeng, A.; Müller, S.; Matsuo, A. Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of Textual Data. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hanyang’s Capital Fortress Selected as UNESCO World Heritage Site. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/briefing/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Chu, H.C.; Roh, H.; Jeong, C. A study on strategies for enhancing the connection between Templestay and nearby trails. Korea MICE Tour. Stud. 2025, 25, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Zhuang, T.; Yan, J.; Zhang, T. From landscape to mindscape: Spatial narration of touristic Amsterdam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institution | Year | Data |

|---|---|---|

| Seoul Metropolitan Government https://www.seoul.go.kr/ (accessed from 20 June 2025 to 17 July 2025) | 2024 | 2 Seoul Trail 2.0 [5] |

| 2024 | 3 2023 Seoul Survey [58] | |

| 2022 | Seoul Hiking Tourism Center [6] | |

| 2019 | 3 Seoul White Paper [59] | |

| 2017 | 3 Seoullo 7017 White Paper [13] | |

| 2013 | 2 Vision 2030 for a Pedestrian-Friendly Seoul [16] | |

| 2006 | 3 Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project White Paper [14] | |

| The Seoul Institute http://seoul.go.kr/ (accessed from 25 June 2025 to 21 July 2025) | 2023 | 3 Study on establishing a master plan to promote leisure culture in Seoul’s parks and forests [60] |

| 2015 | 3 Transition from a vehicle-oriented city to a pedestrian-friendly city [54] | |

| 2014 | 3 Seoul Trail management and operation plan [61] | |

| Korea Forest Service https://www.forest.go.kr/ (accessed from 30 June 2025 to 17 July 2025) | 2025 | 3 Korea Forest Service self-evaluation report [62] |

| 2022 | 3 Survey on national awareness of mountain climbing and forest trail experience [9] | |

| 2021 | 3 Survey on public awareness of hiking and trekking [10] | |

| 2020 | 3 Survey on public awareness of forest recreation activities [11] | |

| 2018 | 1 The Sixth National Forest Plan (2018–2035) [63] | |

| 2008 | 1 The Fifth National Forest Plan (2008–2017) [64] | |

| 2005 | 1 Forestry Culture and Recreation Act [55] | |

| Korea Forest Welfare Institute https://www.fowi.or.kr/ (accessed on 17 July 2025) | 2021 | 3 Korea Forest Welfare Institute Sustainability Report 2021 [65] |

| Ministry of Land, Transportation and Infrastructure https://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 June 2025) | 2005 | 1 Act on Urban Parks and Green Areas: planning of parks, forestry, agriculture, water, and infrastructure to create a more interconnected and integrated network of urban green spaces [18] |

| Ministry of Environment https://me.go.kr/ (accessed on 20 July 2025) | 2019 | 2 The Fifth National Comprehensive Territorial Plan (2020–2040): Visions and Strategy for Korea’s Green Transition 2040 [66] |

| 2019 | 3 The Transformation of Urban Park and Green Space Policy for Sustainability [67] |

| Time | 1960–70s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s–Present | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | Forest rehabilitation. | Promotion of urban forest recreation at the national level. | The Seoul Municipal Government established its own park management plan based on local autonomy. | Implementation of inclusive landscape governance, including forest welfare promotion and revival of the green network through urban regeneration. | Promotion of walkable urbanism through pedestrian-centered landscape planning, in cooperation with multiple ministries and municipal plans. | The green network is further specified to support a sustainable urban lifestyle for residents. | |

| Municipal Level | 1988 Seoul Olympics. | Namsan Renaissance Project (2009) improving accessibility to nature. | Seoullo 7017 (2017), the first elevated park converted from a 1970s overpass. | Seoul Trail 2.0 (2024) introducing metro + trail model by amendment of 8 districts to 21 segments. | |||

| Establishment of Green Seoul Bureau (2005) as citizens’ Green Seoul Committee. | 2030 Seoul Parks Green Area Master Plan (2015) expanding green spaces. | Garden City Seoul Plan (2023) aiming 5 min Garden City Seoul initiatives. | |||||

| Establishment of the Han River Citizen Park, Olympic Park, and Seoul Grand Park. | Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project (2003–2005), 10 km restored waterway from historical resources. | Seoul Dulle-gil (Seoul Trail) (2014), eight district courses on the outskirts of Seoul, stretching a total of 157 km and encircling the city’s 11 mountains. | Seoul Hiking Tourism Center (2022) operated by Seoul Tourism Organization, promoting the city’s hiking tourism content, and offers services (e.g., hiking gear rentals). | ||||

| Restoration of Senggwak-gil (fortress wall trail) (2010–2012). | |||||||

| State Level | Park Focused | Park Act (1967), the first designation of a national park. | Korea National Park Service (1987) under the Ministry of Construction. | Korea National Park Service (1987) under the Ministry of Environment. | Act on Urban Parks and Green Areas (2005) enacted by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport to promote a healthy, cultural, and comfortable urban lifestyle for citizens through urban nature. | Act on the Establishment and Management of Yongsan Park (2016): conversion of former US military base into a national park. | 22 National Parks, including Bukhansan National Park within Seoul. |

| Establishment of Urban Park Act (1980) focusing on the concept of parks in cities. | Last amendment to the Act on Urban Parks, Green Areas (2015). | ||||||

| Forestry Focused | 1st National Forest Plan (1973–1978) focusing on forest restoration. | 2nd National Forest Plan (1979–1987) promoting public interest in forests. | 3rd National Forest Plan (1988–1997) designating of recreational forests in urban areas. | 4th National Forest Plan (1998–2007) enhancing the socio-cultural value of forests, including forest recreation. | 5th National Forest Plan (2008–2017) constructing national forest paths and promoting the forest welfare system. | 6th National Forest Plan (2018–2035) aiming re-creation of the city as a forested space for life with forests. | |

| Korea Forest Service (2013) under the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs. | |||||||

| Korea Forest Service becoming an independent administrative agency (1998). | State Forest Administration and Management Act (2005) promoting welfare services by enhancing the recreational function of forests. | Forest Welfare Promotion Act (2015) promoting people’s health and quality of life by providing systematic forest welfare services by establishing Korea Forest Welfare Institute (2016). | |||||

| Establishment of Korea Forest Service (1967) as an external agency under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. | Forestry Culture and Recreation Act (2005) focusing on conservation, use, and management of forestry culture and forest resources for recreation. | Forest Education Promotion Act (2011) promoting awareness of the value of forests through forest education. | |||||

| Amendment of the Cultural Heritage Protection Act (2010/1962) including mountains as natural monuments. | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, L.; Jeong, C. Linking Walkable Urbanism and Hiking Tourism in a Mountainous Metropolitan City. Land 2025, 14, 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091857

Kim L, Jeong C. Linking Walkable Urbanism and Hiking Tourism in a Mountainous Metropolitan City. Land. 2025; 14(9):1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091857

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Lankyung, and Chul Jeong. 2025. "Linking Walkable Urbanism and Hiking Tourism in a Mountainous Metropolitan City" Land 14, no. 9: 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091857

APA StyleKim, L., & Jeong, C. (2025). Linking Walkable Urbanism and Hiking Tourism in a Mountainous Metropolitan City. Land, 14(9), 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091857